On Friday night the Mets played one of those OBJECTS IN MIRROR ARE CLOSER THAN THEY APPEAR games: They seemed to have the Pittsburgh Pirates well in hand for a second straight night, starting with Taijuan Walker [1] not giving up a hit until the fourth. The Mets repeatedly looked on the verge of knocking the Pirates out, but that decisive blow never landed — the membrane between “hard fought” and “laugher” remained stubbornly impermeable.

Walker pitched ably into the eighth but ran out of gas, giving up a rapid-fire single and then a homer to Oneil Cruz [2]. Cruz is going to be a superstar — he’s an action figure cloaked in human form, with a wonderfully expressive face and lightning in his throwing arm and wrists — but first he needs to go through the struggles many a young player experiences. The Mets have seen the greatness he’s capable of along with the lesser moments he hasn’t yet escaped; with one swing, Cruz brought the Pirates within a single skinny run.

Edwin Diaz [3] — yes, he does still pitch for the Mets — kept the Pirates at bay in the eighth, but the Mets let another chance go by, and when Diaz returned for the ninth, the layoff had clearly not been to his benefit.

Diaz walked leadoff hitter Ben Gamel [4], who was replaced by speedster Greg Allen [5] — who promptly stole second. Luis Guillorme [6], who’d taken the throw, immediately called for a review.

Guillorme is often emphatic in such respects, but the Mets had nothing to lose, so they sent their case a little west for Chelsea for review. Said review quickly determined that Guillorme was seeing the world as it was and not as he merely wished it to be — he had dropped his leg in front of the base, allowing Allen to touch that and not his actual goal. (My goodness did we miss Guillorme.) The Pirates’ runner in scoring position ceased to be, Diaz fanned Ke’Bryan Hayes [7], and Cal Mitchell hit a drive to the fence but only to it, no farther.

The Mets had survived, emerging victorious not by administering a bludgeoning but by making slightly fewer mistakes than the opposition. Which still counts as a win [8] — the most valuable commodity imaginable as September bears us on the way to wherever it is we’re headed.

* * *

[9]Greg noted [10] the death of John Stearns [11], the speedy and tough catcher who was one of the rare reasons to watch the Mets of the post-Massacre era. Like my blog partner, I was thrilled to see Stearns at Old-Timers Day, tragically reduced by the illness that would claim his life but obviously pleased to be among his peers. I blanched at the idea of what the effort must have cost him, unaware of how right that was — and how few days remained to Stearns.

[9]Greg noted [10] the death of John Stearns [11], the speedy and tough catcher who was one of the rare reasons to watch the Mets of the post-Massacre era. Like my blog partner, I was thrilled to see Stearns at Old-Timers Day, tragically reduced by the illness that would claim his life but obviously pleased to be among his peers. I blanched at the idea of what the effort must have cost him, unaware of how right that was — and how few days remained to Stearns.

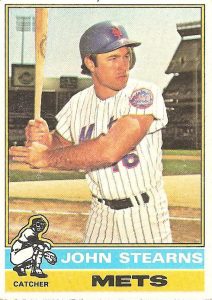

My first memory of Stearns came not from a ballgame but from a baseball card — Stearns’ ’76 Topps card, in which he’s represented by the Michigan blue and maize that still read to me as semi-official Mets colors.

It’s a posed shot, of course, but an awfully good one: The fingers of Stearns’ bottom hand have come off the bat, as if eager for trouble; his body is coiled, poised for imminent violence; and his expression suggests he’s more than ready for “imminent” to become “here and now.” As a kid and a newcomer to baseball, I was fascinated by that card — and pleased to discover the man pictured was worthy of it.

Stearns played one game for the Phillies before coming to the Mets as the best piece of the Tug McGraw [12] trade and was a four-time All-Star for us, a legendarily tough catcher unafraid to mix it up with Gary Carter [13], Dave Parker [14] or anyone else who dared challenge his guardianship of home plate. A bad elbow ended his career just as the Mets were returning to relevancy — he appeared briefly at the tail end of ’84, but the team’s mid-80s revival took place without him. But he stayed with the game, serving as third-base coach for the 2000 Mets and famously exulting about Mike Piazza [15] that “the monster’s out of the cage!”

To younger Mets fans of that era, maybe, he was just a coach. But I cherished him as a survivor of a barren era, one who’d missed the first glory period after his career but been rewarded for staying the course and granted a role in the next one. For veteran fans like me, that made him something of a kindred spirit — even if we never played the game and could only watch those who, like Stearns, did so with such skill and ferocity.