How is it possible Maury Wills stole only 22 bases at Shea Stadium?

In watching a montage of the thievery that made him famous, it seemed every third clip was Maury swiping second at Shea. That probably owes to the Mets recording and preserving on film more of their game footage than those franchises outside media capitals. When you see highlights of baseball greats from the 1960s and 1970s, you see mostly postseason games, All-Star Games and Mets games. There were only so many baseball greats in Mets uniforms then, so it’s often those in road grays or powder blues who are featured throwing strikes, hitting bombs or running wild.

Maury Wills, who died this week a little shy of his 90th birthday, ran wild. He stole bases literally like nobody before him and he stole bases so that everybody who came after him followed in his footsteps…if they could keep up. Few have.

Wills, shortstop mostly for the Los Angeles Dodgers between 1959 and 1972, was known best for stealing 104 bases in 1962. He was known as a more complete player than that, but like Roger Maris socking 61 home runs in 1961, it was his instant identifier. Those Dodgers of the early ’60s were as much about Maury Wills on the run as they were Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale on the mound. Being in a media capital themselves, they were as recognizable as any baseball players in America.

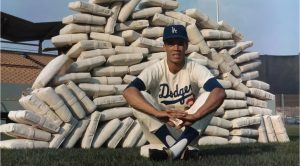

You couldn’t watch Wills, even in the latter stages of his career, which is when I saw him, and not be amazed that he had piled up triple digits in a category where that seemed unfathomable. A photographer once posed him in front of 104 bases. That picture made the rounds quite a bit when Wills was still taking second on hapless batteries. Gaping at the image made his accomplishment only more incomprehensible to me. (Rooting for the generally lead-footed Mets, who never had anybody steal more than 31 bases during their first fifteen seasons, only added to my awe.)

Lou Brock broke Wills’s record in 1974. By then Wills was part of the NBC Game of the Week crew. I saw him wearing his headset while taking part in an Old Timers game at Shea. The Cardinals were the Mets’ opponent that Saturday. Lou and Maury posed together. Brock was already chasing down Wills, eventually totaling 118 bases on the season. It was immense and impressive, just as Rickey Henderson’s astounding 130 bags in 1982 would be, yet like Maris’s 61, Wills’s 104 somehow looms larger as a single-season record than the greater quantities that succeeded it.

Lou Brock broke Wills’s record in 1974. By then Wills was part of the NBC Game of the Week crew. I saw him wearing his headset while taking part in an Old Timers game at Shea. The Cardinals were the Mets’ opponent that Saturday. Lou and Maury posed together. Brock was already chasing down Wills, eventually totaling 118 bases on the season. It was immense and impressive, just as Rickey Henderson’s astounding 130 bags in 1982 would be, yet like Maris’s 61, Wills’s 104 somehow looms larger as a single-season record than the greater quantities that succeeded it.

He broke a hundred before anybody. He broke a record that was set by Ty Cobb. He broke a record that had stood since 1915. He woke up an entire sport’s dormant skill set. One shouldn’t say “nobody” stole bases en masse in the decade before Wills came along, but it was practically a lost art. Maury made the basepaths a canvas few were used to seeing. That method of gunning by running, personified at the high end by the likes of Wills, Brock, Henderson and Tim Raines and injecting the game as a whole with hold-onto-your-hat excitement, would take off and not slow down until the 1990s.

Lest we think of Maury Wills as someone who only took from the Mets (54 steals overall), the man attempted to give something back to us. In the Spring of 1993, at the invitation of his old Dodger teammate and current Met manager Jeff Torborg, Wills put on a Mets uniform and served as baserunning instructor for a few weeks in Port St. Lucie. The Mets were thought to have the makings of a potential baserunning machine — they already had Vince Coleman, Howard Johnson and Ryan Thompson and had just added Tony Fernandez — and how could they not benefit from a master class? Not only did Maury steal like crazy, he was a state-of-the-art bunter. “I can’t make them faster,” Wills said, “but I can get them from first to third, across the plate from second.”

That all the expert coaching in the world couldn’t help the preternaturally doomed 1993 Mets get to first base let alone out of last place was hardly Wills’s doing. Maury tried to enhance Vince’s toolkit in particular. Coleman had outdistanced Wills’s 104 SBs three times in St. Louis, where the artificial turf helped him find his way on base. On Shea’s natural grass, Coleman had to try to rev up his offense on his own. “It’s a miracle he’s done what he has without bunting,” Wills said of his primary pupil. They worked together in camp, Vince showed a modicum of acumen, but…well, it was Vince Coleman on the Mets. It wasn’t a bad idea, though. In 1965, the club had hired track and field legend Jesse Owens to coach baserunners in Spring. At least with Maury Wills, they had a ballplayer.

The same could be said of the Dodgers all those years.

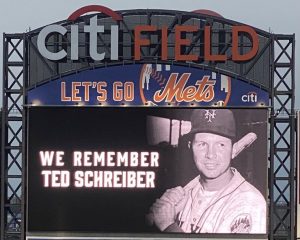

That’s something Ted Schreiber allowed himself to wonder in the years following 1963, his only year as a Met, his only year as a big leaguer. “To this day,” he admitted to author Bill Ryczek in the 2008 book The Amazin’ Mets, 1962-1969, “I don’t know how much ability I had.” Ted played on a club that wasn’t exactly lighting the National League ablaze, and you’d guess any youngster with a glove and a clue would have been welcome to show his stuff. Schreiber, 24, was an infielder the Mets went out of their way to acquire, drafting him as a minor leaguer from the Red Sox the previous winter. The previous summer, they’d lost 120 games. Any newcomer should have figured to get a long look, especially one who grew up a relatively short drive from the Polo Grounds.

Brooklyn native (as such, a contemporary of Joe Torre and Bob Aspromonte) and St. John’s alumnus Ted Schreiber, who passed away at age 84 on September 8, should have been right at home on the Mets. Johnny Murphy, who ran scouting, knew Schreiber from the time they shared in the Boston organization. Murphy convinced George Weiss to grab the infielder with the first pick in the Rule 5 draft. Sheriff Robinson, in the ’70s the Mets’ first base coach but in 1963 one of their minor league skippers, had Ted when he ran the Allentown affiliate for the Red Sox. His impression: “Great scrapper. Good power to right-center. Adequate speed. Good arm. Very cocky.” Sounds like a boy straight outta Brooklyn in the 1950s. The Mets got the man they wanted, but maybe not the man their main man — Casey Stengel — wanted. Schreiber had a hunch he just wasn’t Stengel’s guy and, as a result, found himself overlooked early in the season and later, after he was recalled from Buffalo. Only 39 games in the majors, only 55 times to bat.

Aside from him and his manager not necessarily being on the same page, there was the issue of a lack of pages in New York. As a hometown kid, Ted had the savvy to believe he could be a cause for newspapers looking for a good story. Except in the Spring of 1963, the newspapers went on strike, so whatever the James Madison High grad had to offer in the way of colorful copy wound up theoretical. Then there was the issue of not having “a rabbi,” as Schreiber put it, no coach looking out for him the way he noticed Cookie Lavagetto taking Larry Burright under his wing or Solly Hemus mentoring eventual Rookie of the Year runner-up Ron Hunt. All he craved was more of a chance on a club that was losing 111 games with him mostly on the bench — and, as Ted would recall for his SABR biography in the 2000s, “where I was positioned, I needed a long bat if I was going to get a hit.”

Nevertheless, when Ted saw action in September, history would show it was momentous. On the eleventh of that month, with the San Francisco Giants visiting their old haunts, Schreiber entered the game for defense at third base in the top of the ninth inning and Al Jackson protecting a 4-2 lead. The first batter of the inning, Jim Davenport, grounded to Ted, who threw to Tim Harkness for the first out. With two outs, San Fran second baseman Ernie Bowman stepped up, the last obstacle left between Jackson and a complete game victory. Like Davenport, Bowman grounded to third. Like before, Schreiber fielded the ball and threw it to Harkness. Bowman was out. The Mets had won.

Nevertheless, when Ted saw action in September, history would show it was momentous. On the eleventh of that month, with the San Francisco Giants visiting their old haunts, Schreiber entered the game for defense at third base in the top of the ninth inning and Al Jackson protecting a 4-2 lead. The first batter of the inning, Jim Davenport, grounded to Ted, who threw to Tim Harkness for the first out. With two outs, San Fran second baseman Ernie Bowman stepped up, the last obstacle left between Jackson and a complete game victory. Like Davenport, Bowman grounded to third. Like before, Schreiber fielded the ball and threw it to Harkness. Bowman was out. The Mets had won.

It was the final game the home team ever won at the Polo Grounds. We’re talking about a ballpark that dated to 1911 (four years before Ty Cobb stole his 96 bases) and a site, Coogan’s Hollow, that had been hosting big league baseball since 1889. Generations of New York Giants fans had ascended to the Bluff above or out to the Ninth Avenue El buoyed by triumph. It didn’t happen too often for Mets fans. When it happened one last time, it was sealed by Ted Schreiber.

The 1963 Mets being the 1963 Mets meant that the last game they won at home wasn’t close to being the last game they played at home. The Mets had seven games left at the Polo Grounds on that homestand after September 11. They lost all seven (including the major league debut of Cleon Jones). On September 18, the Mets pulled down the shades on the matron of the majors for good with a 5-1 defeat at the hands of the Phillies. The last batter? Ted Schreiber, who grounded into a double play that the batter would remember as a ball second baseman and future Met coach Cookie Rojas “made a great play on”.

Schreiber’s last game in the majors came on September 29, at Houston, the season-ender, also a loss. Brand new Shea Stadium beckoned for the Mets, but 1964 would find Ted back in the minors, where he felt he had proved himself by 1963, long after signing with the Sox in 1958. From the Mets system, he’d go to the Orioles’, where he wouldn’t get the call to Baltimore but would provide one more Metsian footnote: at Rochester, he’d take the roster spot of a rising infielder and future manager. We’d come to know him as Davey Johnson.

Ted did not pursue lifer status in baseball. He completed his degree at St. John’s and instead took up teaching. It may have been the role for which he was meant. Visit his Ultimate Mets Database Page, click on the Fan Memories header and learn what he meant to students who remembered him decades after crossing paths with him. You might even say he became their rabbi.

In the end, one supposes, lucky to have lived to almost 96 years of age. Longevity in and of itself isn’t the point when we think about how long Joan lived, a lifetime that lasted until September 17, 2022. The point for all of us cheering her and her cause on from the sidelines was that Mrs. Hodges would get to see her husband, Mr. Hodges, inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

We watched Joan Hodges get her hopes up and then have reality let her down for some fifty years, and that was after reality dealt her and her family a crushing blow. Some luck. A heart attack took her husband Gil two days before he was to turn 48. We lost the manager who led us to a World Series title and respectability all at once. She lost the love of her life. Her children lost their father. Whatever else they would do, Joan, son Gil Jr. and daughters Irene and Cindy would make it their business to see Gil get his due.

So we got to know Joan to an extent that we considered her an essential member of our baseball family. We saw her solemnly accept Gil’s jersey from GM Bob Scheffing when No. 14 was retired in 1973. We saw her at anniversary celebrations of the 1969 Mets. We saw her whenever there was an event commemorating the franchise’s proudest milestones, because pride in the Mets didn’t really enter the picture until Gil Hodges took over as manager. Joan represented Gil for as long as health would allow her. The kids, long adults by the 21st century, would, too, but it was Joan we instantly recognized on TV, in interviews, at Shea. Joan was always gracious, always classy, always selfless. She was making the appearances she did on behalf of a man who’d been gone since 1972. We never forgot Gil Hodges. Maybe it’s because we have a strong memory. Maybe it’s because Joan Hodges wouldn’t let us.

One suspects had Gil lived he wouldn’t have said one word on his own behalf for the Hall of Fame. That’s not who he was. But he was a Hall of Famer, and Joan knew it, the kids knew it, we knew it. It took a half-century to convince those who could do something about it. As the decades went by and Gil went unelected, we couldn’t help but wonder if Gil’s day would ever come, and if it was gonna come, would the woman to whom it meant more than anything be around to see it?

We got our answer on December 5, 2021. The most revered manager the Mets ever had in Queens, the ballast of the powerhouse Dodger lineup in Brooklyn, a first baseman who by all accounts could’ve given Keith Hernandez defensive tips, was chosen for Cooperstown, scheduled for induction in the summer ahead. By this point, with their mom not up for traveling, one of the kids would have to head Upstate and accept. But Joan, still living in the Borough of Churches all these years later, still keeping the candle lit for her love and her cause, would be able to watch it on TV. Whatever was on her mind in her final weeks, she could think of her husband as a Hall of Famer and know it wasn’t only her thinking it.

Though many of us came to picture Joan as the vigilant widow, smiling through perennial disappointment, after she passed, I went to YouTube to see her in a different context. It was the best context in the world: October 16, 1969, Mets 5, Orioles 3 on the scoreboard, Mets 4 Orioles 1 in the Series. Lindsey Nelson’s on assignment for NBC interviewing anybody and everybody. Before he can direct his attention to the players, he is compelled to exchange words with balding, clubby men in suits far less colorful than his own. Then, like a blast of Retsyn from a freshly popped Certs, appears a lady in a green-and-white checkered coat with fur-lined collar, formidable dark red coif, and eyes protected from flying champagne by shades stylish for any era. She could very well be one of my mother’s friends from the beauty parlor.

“Here’s Mrs. Gil Hodges,” Lindsey informs the viewing audience. “Hello, Joan. He was here,” he tells her in case she just happened to be wandering by in search of her spouse.

“Here’s Mrs. Gil Hodges,” Lindsey informs the viewing audience. “Hello, Joan. He was here,” he tells her in case she just happened to be wandering by in search of her spouse.

“Lindsey, oh I just can’t believe it!” is her high-pitched response. “It’s been a year of miracles, and it’s marvelous, really, really marvelous!”

And then Joan Hodges moves on, presumably finding her husband so they can share this greatest of moments together. You’d like to believe that somewhere they’re sharing it still.

National League Town remembers Mr. Wills, Mr. Schreiber, Mrs. Hodges and Mr. John Stearns on its current episode. You can listen to it here.

RIP.

I never saw Wills play, but he was the subject of my favorite baseball lyric of all time (courtesy of Danny Kaye):

Maury goes, the catcher throws

Right from the solar plexus

At the bag, he beats the tag

The mighty little waif

And umpire Conlon says,

“YER OUT!!!”

OUUUUT???!!!

It’s good to know that Wills had an association with the Mets, however brief. Three classy individuals – thanks for sharing their stories.

I was waiting for that tribute to Mrs. Hodges, Greg, and you were absolutely spot-on, as usual.

She and Mrs. Payson were a big part of what made us great.

Thank you for such a great post. I particularly appreciate the segment on Ted Schreiber. It’s always nice to learn more about Mets from the early days when they toiled in the wilderness that was The Polo Grounds.