It’s not every day your favorite Major League Baseball franchise registers its 5,000th regular-season loss. The day our favorite Major League Baseball franchise registered its 5,000th regular-season loss, the skies clouded up all morning and afternoon; began to mist and drizzle as evening set in; and then began to pour down through the night. Somewhere between the drizzling and the pouring, and ahead of Saturday’s rainout, there was just enough time to get in that 5,000th loss.

The Mets played five innings of losing baseball on Friday night. Well, four innings of tying baseball and one inning of losing baseball. It’s a ratio that doesn’t look so bad until you remember how definitive one losing inning versus none involving winning can be. In this case, after David Peterson and Max Fried each put up zeroes for four innings, Peterson cracked. He almost held it together. Got one out in the fifth. Was on the verge of withstanding a single from Eddie Rosario and a double from Old Friend™ Kevin Pillar when he induced Michael Harris II (how nice knowing there are multiples of young Braves) to bounce to Brett Baty. Baty in the rain stood and thought about what to do with the presumably wet baseball for a spell, but ultimately and wisely gripped and threw it home to Francisco Alvarez. Alvarez didn’t have to tag Rosario, given that Rosario veered from the basepath toward Astoria, which even a bleeping Brave can’t get away with.

With two out, Pillar on third and Harris having moved up to second while Baty took his time throwing home, all Peterson, who had appeared sharper than he had the rest of April, had to do was take care of Ronald Acuña, Jr. The Mets haven’t yet figured out the best way take care of Acuña is to deny him entry to Citi Field. A solid single brought disgraced Bench Mobster Pillar home with the first run and pushed Harris to third. Really, it didn’t matter where Harris was pushed. He and Acuña would be powered across the plate by the next batter, Matt Olson. Olson rudely directed a baseball into those pavilion seats in front of Shea Bridge.

It was 4-0 and raining. You hoped both conditions would be temporary. You knew permanence loomed because of the ancient rule that says five innings can be an official game if the skies are angry enough to lop off the forthcoming four. The Mets could have scored four or five in the bottom of the fifth to forestall permanence let alone defeat in their role as the home team potentially leading at the end of five soaking innings, but that’s Max Fried out there on the mound. As long as he didn’t slip, fall and not get up, he was gonna take care of the Mets as seems to be his wont. Max Fried’s ERA in 2023 is 0.45. It’s not just us.

Max got through the fifth with minimal fuss. The rain fell with maximum impact. The tarp covered the diamond. I flipped to the Islanders ending their season in overtime. Somewhere along the way I remembered to check back in on the rain delay. It became a rain-shortened final of 4-0. The Mets’ season didn’t end. It didn’t continue strongly, but, we’ll continue to tell ourselves, it was just one game.

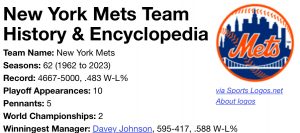

When Fried and Pillar and Acuña and Olson and the rain conspired to defeat the Mets, it knocked us 333 games below .500. Not for this year, but for all years. Our current lifetime record of 4,667-5,000 —— plus 8 ties — carries a lifetime winning percentage of .483. For context, if you apply .483 to a 162-game season, you’d have a team that goes roughly 78-84 every year for nearly 60 seasons. The Mets are in their 62nd season, but a few of them have been shortened by strikes and pandemics and whatnot. The Mets have never posted a 78-84 record at year’s end. The closest they’ve come is 77-85 in 2011, 2018 and 2021; 77-84 in 1991; and 79-83 in 2010 and 2014.

If you remember any of those six seasons, that, on average, is what our entire life as Mets fans has been. Of course we don’t take average into account over the long haul. Extremes make for punchier examples, and we’ve sure taken our punches since coming into this world. You know, if not by heart then in your gut, that we lost our first nine games to begin life, and 120 of our first 160. The losing continued at a slightly less self-defeating pace for the next five or so years. After dropping a Sunday doubleheader at Shea to the Cardinals on June 2, 1968, the Mets’ lifetime record was 341-675.

The Mets were off that Monday. Tuesday they played in Chicago. Jerry Koosman shut out the Cubs, 5-0. From that day forward through Friday night — June 4, 1968, all the way to that tarp staying put on April 28, 2023 — the Mets’ record has been 4,326-4,325. For nearly 55 years, the largest friendly sample size we can cobble, the Mets have been a winning baseball team. Not enough peaks and far too many valleys for our taste, but cumulatively, the past 8,651 Mets games played to a non-tying conclusion have indicated we root for a team you can’t, on average, call a loser.

Even if that’s a soggy hook on which to hang one’s hat after five innings drenched by Max Fried.

To discern an answer, you’d have to fly back in time, over Acuña Jr. and Harris II and the only Fried I’m aware of; over the miseries inflicted by the likes of Freeman and Chipper and those Cy Young pitchers far more annoying than Max Fried; over the brief era when Dale Murphy and Bob Horner gave credence to the America’s Team hype; even before Phil Niekro’s knuckler began to beguile the National League in earnest.

You have to go back to practically the beginning, to when the Braves were Milwaukee’s best. You have to go back to the 1962 Mets ever so briefly hinting that they might not be “the 1962 Mets”. After that 0-9 start, the ’62 Mets got on a roll. Maybe it was just about averages averaging out or regression to the mean or some fancy statistical term that explains eventually you’re gonna win some even if you mostly lose some, but from April 23 to May 20, the 1962 Mets were a winning team, going 12-10 in their previous 22 games. For a team that had played only 31 times in their life, you can’t dismiss 22 games as a small sample size. And the last set of opponents who would dare to slough off the surging Mets’ success would have had to have been the Milwaukee Braves.

Against the 1962 Mets, the 1962 Braves, in a pair of series spanning ten days, went 4-5. That included two doubleheader sweeps over the outfit that featured Henry Aaron, Eddie Mathews, Warren Spahn and a young catcher named Joe Torre. The already laughable Mets took the measure of an aggregation of Hall of Fame talent, and who was laughing now? When the Mets completed their second sweep of those Braves, at County Stadium on May 20, their season and lifetime record was 12-19. Never mind that the eighth-place Mets were leading both Houston and Chicago in the standings and sat only a game from Milwaukee for seventh. Consider the long view. Since 1962, nine different Mets teams have not posted a better record than 12-19 over their first 31 games, which is to say that for a brief, shining moment, the 1962 Mets were en route to not being the worst Mets team (or worst team) ever, and it was largely because the Braves couldn’t beat them.

Then the 1962 Mets continued their road trip, lost 17 in a row, and haven’t been within seven games of .500 lifetime since. They haven’t been within 300 games of .500 lifetime since 2009, but that’s another story. The story we’re trying to tell at the moment is that of the underlying grudge we’d like to believe might be motivating the Braves to beat the Mets as often as they do in the modern era. We’re going with embarrassing Atlanta’s Milwaukee ancestors early and often and our about-to-emerge habit of plucking their unwanted players and giving them the opportunity to blossom in the years following 1962 as the most logical reasons we can come up with. Honestly, that should have been enough to get a potential archrival’s DNA chopping mad.

Carl Willey, the Mets’ veritable ace pitcher of 1963, was somebody the Braves didn’t want anymore. The righty from Cherryfield, Me., languished in the middle of their rotation, somewhere south of Spahn, since his rookie season of 1958. The promise he’d shown initially evaporated a little more each year until Milwaukee was happy to take a chunk of Mrs. Payson’s cash in exchange for his services in Spring Training of ’63. Willey rewarded Met management’s interest by throwing four shutouts in the year ahead, or four more than all other Met righties had combined to throw over the club’s first two seasons. One of Carl’s blankings, a two-hitter over the Phillies, served as pleasing background for Jimmy Piersall’s backwards trip around the bases when Jimmy hit his 100th career home run. Casey Stengel was famously irritated enough by Piersall’s attention-craving act to promise to remove him from the roster on the basis of the Polo Grounds being big enough for only one clown. Willey, on the other hand, inspired nothing but faith in Casey. The night after the Piersall contretemps was a game that technically didn’t matter, but emotionally mattered like nothing before it: the first Mayor’s Trophy Game. How important was it to Mets fans, let alone the Mets’ manager, that the Mets best the Yankees in the Bronx? Stengel brought in Willey to pitch four innings of relief on no days’ rest to make sure the Mets’ lead over his former employer didn’t get away. It didn’t…even if Carl got away from the Braves.

Ron Hunt, the Mets’ first attention-getting youngster (attention received for the right reasons), was also somebody the Braves didn’t want anymore. Ron was a minor leaguer in the Milwaukee system, never getting beyond Double-A for four seasons in the Brave chain. Another cash deal ensued. It paid off handsomely when Ron insinuated himself into the Mets infield in 1963, finished the season as National League Rookie of the Year runner-up to Pete Rose, and literally starred at second base during the Midsummer Classic at Shea in 1964, chosen ahead of every keystone sacker in the senior circuit, including that Rose kid. True, Pete would last longer in Cincy than Ron would in New York, but the Reds had had stars before. Hunt was our first ever, landing in our lap courtesy of the Braves.

In the second half of 1964, while Ron was rising and Carl was recovering — a line drive got him in the jaw in Spring Training and pretty much guaranteed he’d never again be as effective as he’d been the year before — the Mets picked the Braves’ pocket once more. This time, it wasn’t merely money Milwaukee sought. They wanted the Mets’ veteran righty, Frank Lary. The Braves were on the periphery of the pennant race. Maybe Lary would lift them from the middle of the pack into true contention. To get the man known alternately as the Mule and the Yankee Killer (one guess as to which one we consider the most flattering appellation), it would take some cash, yes, but also a 22-year-old righthander who’d been putting up some pretty valuable numbers of his own in the minors since 1961.

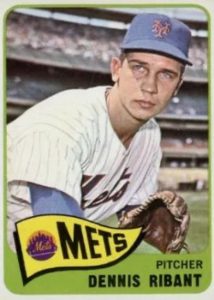

The Braves sent the Mets Dennis Ribant on August 8, and before August was out, Dennis Ribant appeared ready to make us forget Carl Willey wasn’t what he used to be. Ribant was making us look forward. That was the direction fans of a third-year expansion club that had finished tenth and tenth, and was about to finish tenth again, needed to look. We had to have something and someone to anticipate, someone who’d take part in a future that would turn the present of last place into the past as soon as possible.

On August 9, Dennis the Met made his major league debut in relief. Three days later, he made his first start. It didn’t go particularly well: five earned runs over six innings at Pittsburgh. The resulting 5-4 loss dropped the Mets 44 games below .500 on the season and 184 games below .500 in the still nascent life of the franchise. In other words, more of the same.

Five days after that, Dennis Ribant gave Mets fans nothing of the sort. He gave us a glimpse of possibility. At Shea Stadium, in his first home start, Ribant shut out those same Pirates — Hunt’s All-Star backup Bill Mazeroski at second, budding Metkiller Willie Stargell at first, the already great Roberto Clemente in right — on four hits and zero walks in a 5-0 Mets triumph that stirred the imagination. The kid whose future the Braves opted out of fanned ten Buccos. You know how many Met pitchers had thrown a shutout while striking out a double-digit total of batters, Hall of Fame-bound or otherwise? Before Dennis Ribant, there were none.

With Frank Lary and whatever financial resources Mrs. Payson had provided them over the past two years, the Milwaukee Braves didn’t crowd the 1964 National League pennant race to any meaningful extent. They finished fifth. In the offseason, they’d sell Spahn to the Mets. Lary, too, making the Mule and the Yankee Killer also the first Recidivist Met. By 1965, the Braves were already making plans to move to Atlanta in 1966, setting a goodwill template for the Oakland/Las Vegas Athletics of the 2020s. Neither the Milwaukee nor Atlanta Braves were the Mets’ primary concern heading into ’65. We’d have to figure out what to do with all our ex-Braves pitchers.

Spahn would have his moments, as one would imagine the owner of 356 wins and counting when he joined the Mets would, but Warren wouldn’t last in New York. The 44-year-old lefty legend would be released in July and seek his last ounce of contention pitching for San Francisco. Lary, 35, had enough left to entice another pennant hopeful, the White Sox in the other league, to acquire his services from the Mets shortly after Independence Day. Willey, 34, had to go down to Buffalo to regain his form, and his final start of the year showed he could still pitch. He went nine in beating the Phillies on September 25. That turned out to be the final appearance of Carl’s major league career, as he chose retire to Maine rather than chase any further innings on the mound. In fact, none among this trio of ex-Braves pitched in the bigs after 1965.

Ah, but we were looking ahead. We had Dennis Ribant. We had the young man who’d shut down the Pirates in 1964. We didn’t get a game nearly as good from the kid for most of ’65 (he’d be back in Triple-A by June), but toward the very end of the year, on September 28, Dennis threw eleven shutout innings against the team he’d tormented thirteen months earlier. Unlike that breakthrough in August of ’64, the Mets didn’t score a whit for Ribant and he was no-decisioned. Four days later, Rob Gardner would pitch fifteen innings of shutout ball and the entire team was no-decisioned in what went into the books as an 18-inning 0-0 final, the fourth of those eight aforementioned ties in Mets history. It was helluva week for the unrewarded.

Ribant’s and our reward would await in 1966. That, in an individual pitching sense, was the year we had been waiting for since 1962. The ex-Braves farmhand came of age as a Met starter. Having pitched credibly out of the bullpen in April, Wes Westrum handed Ribant the ball against the Cubs on May 8. Dennis went nine and got the win. In June, he notched another shutout victory, over the Reds. His place in the rotation secure, he took off as no Met pitcher before him had. This is not hyperbole. The Mets had some starters do well with little to show for it between 1962 and 1965. Willey deserved better than to go 9-14 in 1963, but he finished with a losing record nonetheless. Al Jackson won 13 for a team that lost 111 in 1963. He also lost 17. Records of that nature came with the Metsian territory.

Cartographer Dennis Ribant drew a new Met map in 1966. He started ballgames and he started winning — him and the Mets. On September 6, when he once again shut down the Reds, his record stood at 11-6. For five years, the idea that any entity within the Mets’ realm could claim an overwhelmingly positive statistical ledger bordered on absurd. Yet here was this still young man we got from the Braves and, unlike a Spahn or a Lary or a Willey, he had his prime on the horizon. On the cusp of turning 25, he was pretty much in the thick of it. Not only was he five games over .500, his earned run average was 2.67. That’s what a good pitcher posts. Dennis Ribant was a good pitcher pitching well and not in hard luck.

Even with a little falloff in fortunes over the final few weeks of 1966, Dennis Ribant finished with the kind of record unfamiliar to the Mets starters who preceded him: 11-9, with an ERA of 3.20. The Mets didn’t finish last. The Mets didn’t lose 100 games. The Mets had a live right arm that had already demonstrated it could consistently get hitters out and have something to show for it.

Come 1967, the Mets would have two players to show for Ribant’s 1966. The Pirates, who perhaps remembered what Dennis had done to them as he was coming along, traded two of their own D-men — Don Bosch and Don Cardwell — to the Mets to have Ribant (along with outfielder Gary Kolb) board their ship. There’s not much need to weave a pattern of foreshadowing from here, not if you’ve been a Mets fan long enough to recognize certain names. Bosch was supposed to fill the Mets’ long-gaping hole in center field. To put it kindly, he didn’t. Cardwell was another in that long line of veteran pitchers in whom the Mets placed their trust when they weren’t quite sure what to do with their youthful counterparts. He started Opening Day 1967 because they weren’t quite convinced another good-looking young righty, only 22 and holding no major league experience, should be granted the honor of that assignment.

So Tom Seaver (whose name fell into a hat once his contract slipped out of the Braves’ hands) waited until the second game of ’67 to debut, and in a matter of minutes, was the best pitcher, young or old, the Mets ever had. Cardwell’s role as ace was evanescent. Turned out Don would have a more important part to play in the Mets teams that were coming together in 1967 and 1968. There’d be a lot of young pitchers proving themselves more than capable of carrying the load, but that kind of staff inevitably benefits from a savvy veteran. The swiftly arriving future would belong to Seaver, Koosman, Ryan, McAndrew and Gentry. Enough of the present that accompanied it into existence was spoken for by Cardwell. Don won 20 games for the Mets in the final three seasons of the 1960s, including eight in 1969.

Perhaps had the Cardwell trade never been made, we’d be just as easily listing the name Ribant alongside those other then-young pitchers who made the 1969 Mets “the 1969 Mets”. The story, as we tell it now, has Don playing a vital mentoring role, not to mention an important one that involved starting 21 games in ’69. As it happened, Ribant would pitch for a team that would win the World Series in the late 1960s. He was a Detroit Tiger in 1968, if not for long. The Pirates had sent him to his hometown team after a decent enough 1967 (9-8). The Tigers swapped him to the White Sox for experienced bullpen help (38-year-old Don McMahon) midway through ’68. There’d be some bouncing around from there. Dennis last pitched in the majors in 1969 and in the minors in 1973. Ribant lived fifty years beyond his last professional pitch, dying this past week at the age of 81.

If, like me, you never saw Dennis Ribant pitch as a Met, you can be comfortable historically slotting him in that circle of players who necessarily had to move on to build the 1969 world champions (who, incidentally, swept the Braves on their road to the World Series). Ron Hunt had to go in order to get Tommy Davis, and Tommy Davis had to go to in order to get Tommie Agee. Tommie Agee had to be in center field in order for the Mets to go all the way, but both Hunt and Davis expressed regret they couldn’t stick around long enough to experience 1969 as Mets. Could you blame them? Each man, who played deep into the 1970s, made the Mets the best they could possibly be in the years prior to 1969, when the franchise was piling up losses despite their individual standout efforts.

“It killed me” to be in that circle, Ribant told author Bill Ryczek. “It broke my heart when I was traded to the Pirates. It took a while to get used to it because I loved New York. I was the first Met pitcher to have a winning record. It was a big disappointment.”

Technically, disappointment was what existed around Ribant. Actually, maybe what defined the Mets whose ranks Ribant joined wasn’t disappointment. How can you be disappointed when you’ve learned not to expect anything good? By pitching as he did that first start at Shea in 1964 and then for the bulk of 1966, Dennis upended that sad state of affairs. Before it could be clearly forecast that the Mets were one day fairly soon going to be the best in their game, we needed a sign that that day was coming, even if that sign didn’t lead directly to that day. In the middle of the 1960s, when Met losses were the rule, Dennis Ribant proving the exception represented a life preserver to the hopes of Mets fans who lived for the day when being a Mets fan would be about expecting something good.

That’s quite a circle to be in, too.

That first sweep of a Braves doubleheader in early 1962 was remarkable in several ways. In the first game, Spahn and the Braves were leading 2-1 in the bottom of the ninth when Hobie Landrith, the first Met draft choice, hit a 2-run pinch homer to walk it off. It was his only Met home run and he was soon traded to Baltimore for Marvelous Marv. The second game was tied 7-7 in the bottom of the ninth when Gil Hodges hit a walk-off home run to win 8-7. Craig Anderson was the winning pitcher in relief in both games to move his record to 3-1. He never won another game, losing 19 in a row. I was at that doubleheader and it was a factor in my becoming a Met fan.

Great fan origin story.

Interesting look, but lest we forget that for a brief moment, Tom Seaver himself was an Atlanta Brave, but for those two pesky irrelevant games he threw for USC.

USC played two games, but Seaver wasn’t even involved.

I think all of these slights and insults the Mets sent the Braves’ way in the 60’s could be bundled together and still wouldn’t come close to what really must have kept them up at night. The Braves were the team that screwed up the signing of Seaver such that the Mets won the lottery for his services. You could look it up ( I just did).

Oh, that. (The Seaver signing incident somehow slipped my mind this morning; I’ve parenthetically noted it above.)

“You know, if not by heart than in your gut, that we lost our first nine games to begin life, and 40 of our first 160..”

Did you mean we lost 100 of our first 160 games (and 2 rainouts which we counted as almost wins–after all we can’t lose today!.

“Carl Willey, the Mets’ veritable ace pitcher of 1963, was somebody the Braves didn’t want anymore. The righty from Cherryfield, Me., languished in the middle of their rotation, somewhere south of Spahn, since his rookie season of 1958. The promise he’d shown initially evaporated a little more each year until Milwaukee was happy to take a chunk of Mrs. Payson’s cash in exchange for his services in Spring Training of ’63. Willey rewarded Met management’s interest by throwing four shutouts in the year ahead, or four more than all other Met righties had combined to throw over the club’s first two seasons. One of Carl’s blankings, a two-hitter over the Phillies, served as pleasing background for Jimmy Piersall’s backwards trip around the bases when Jimmy hit his 100th career home run. Casey Stengel was famously irritated enough by Piersall’s attention-craving act to promise to remove him from the roster on the basis of the Polo Grounds being big enough for only one clown”

Ah yes, My 1st Mets games @ Polo Grounds– a DH sweep of Filthies by Al Jackson & Carl Willey-and Piersall’s backwards jaunt around the bases..

Now 60 years later……..

Great writing and memories, although I swear I can recall thousands of thoses losses…OY!

Subbed wins for losses. 120 of 160 lost (since fixed), but you knew that in your gut.

Thanks for this walk down memory lane (the only walking I will be doing on this shitty Saturday). Your comments about Dennis Ribant sent me down a rabbit hole. In 1966 our Bay Ridge band of Tennagers included a certain Diane B., whom I have not thought about in at least 50 years.

And she LOVED Dennis Ribant, even had an autographed “to Diane” picture of him. As I recall, his being “cute” had a lot more to do with her adoration than his 11-9 record. She was cute too.

And in today’s rainy day Internet rabbit hole, I found Diane. No pictures, but a picture of her daughter, a Psychiatrist, who looks just like her. I’m happy for both of them, and for the memories.

Thanks again.

Here’s to Dennis, Diane and the daughter!

Thank you for not mentioning a pitcher who moved between these two franchises in more recent years. This story is complete without him.

I didn’t mention Pete Smith or Mike Remlinger, either.