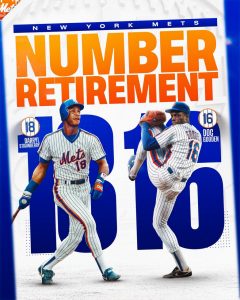

Darryl Strawberry [1] was coiled to swing. Doc Gooden [2] was set to fire. The seconds in which they locked in constituted the most compelling moments in sport, maybe life, in their time at the core of our consciousness. The results tended to tell you why, but it was the anticipation that had us leaning forward. Anticipation will do that.

I anticipate 2024 for the raising of Strawberry’s 18 and Gooden’s 16 to Citi Field’s bustling rafters, two retirement ceremonies whose announcement [4] appropriately came a little out of left field on Thursday, unless you were watching the Mets intently (was there any other way?) in the days of Darryl and Doc. Had you been magically transported from 1984 forty years forward and landed to witness 18 and 16 hanging high atop a facility in the general vicinity of Shea Stadium, one of your most logical questions might be, “How do they keep those placards so immaculate, so looking like new, considering how long ago the Mets must have retired the numbers of the most spectacular hitter and the most spectacular pitcher they ever brought to the majors?”

Then, once you got your bearings, maybe you’d ask why the Mets are so modestly displaying only a single championship banner from the decade when Doc and Straw broke in. You’d probably have lots of questions.

What we know in the present, with four decades of hindsight, is that Darryl Strawberry was the most phenomenal position player the Mets ever developed or acquired in their first sixty years of operations, and that nobody ever regularly took control of a baseball game with such total unhittability on behalf of the Mets as Dwight Gooden. In order of the efficacy of his five tools, Straw hit with power, ran, threw, hit and fielded, very much able to do it all, very often doing tons of it. Doc needed two pitches to get batters out, and routinely took care of almost all of them with a high fastball and a curve that dove as if on an underwater treasure hunt.

To call them both electric is validation for Thomas Edison’s wildest hopes and dreams. To call them successful speaks to what they contributed to our decreasingly wild hopes and dreams as the early 1980s gave way to the middle 1980s. When Bob Murphy closed his call of the final out of the 1986 World Series with, “The dream has come true,” there was nothing generic to Murph’s championship coda. The Mets fan dreamed of a reality like the one forged largely by Darryl and Doc before the Mets fan ever heard of Darryl and Doc, before Darryl and Doc ever heard of the Mets. It and what these two young men represented stood impossibly far away before we encountered and embraced them individually, professionally and in the company of teammates assembled, in practice, to make the most of what they had to offer. When they channeled their respective talents and mastered their respective crafts, the world in which we yearned to live — wherein everything was about the Mets, not just for us but for everybody who peeked their head into big league doings — came to exist. The Mets were its centerpiece, its capital, the axis on which it spun. As of October 27, 1986, the Mets were its champions.

But much of the real fun was in the anticipation, the hoping, the dreaming, and all of it coming to pass, first via the uncoiling of Strawberry’s bat in 1983 (when he won Rookie of the Year) and then the firing of Doc’s first deliveries in 1984 (when he won Rookie of the Year). The Mets climbed from Nowheresville, where they’d resided approximately forever, to somewhere close to winning it all, then even closer, then winning all of it. That was Darryl swinging, Doc throwing, not a few other very important Mets doing their things, and the chemistry and appeal and excitement and immersion generated by this New York Mets scene jumping off the charts. If you were to choose, you’d choose never to retire from the era in which Darryl was up with a chance to some damage and Doc was a strike away from setting down the side in order.

It felt like it would last forever. It didn’t. They felt like they’d last forever. They couldn’t. They couldn’t last as Mets and they couldn’t last as the best at what they did for as long as every concerned party, from the most seasoned scout to a reasonably discerning fan, would have projected. Darryl Strawberry and Dwight Gooden were people. People who were absolutely great at playing baseball, people who played absolutely great baseball in tandem, people who played absolutely great baseball on an absolutely great baseball team. They didn’t do it forever. They did remain people.

The 1986 Mets’ world championship banner sits adjacent to the 1969 Mets’ world championship banner over in the right field rafters. Then the championship banner parade glides down a notch to National League championships, none won from the days of Darryl and Doc or any of their contemporaries. Squint and you’ll see something about a division title a couple of years later. Go back to the area over the left field seats next year, and there will be Nos. 18 and 16, anyway. They did so much, just not everything. They won the big one, just not multiples of them. They were who they were. They have persevered as people and were around Thursday to accept the news about their numbers with gratitude and pride.

Their numbers, once they are hung, will be the eighth and ninth retired specifically by the New York Mets. Two — 37 and 14 — rose to rafters to honor managers, so we’re talking seven players out of 1,216 Mets overall, as of the day the Strawberry/Gooden announcement was issued, receiving the franchise’s ultimate honor. One, 24, is a category of its own. So let’s take Willie Mays out of the equation. Willie Mays will always belong in his own category as a baseball player. Willie Mays defies equations.

Of their 1,215 baseball players who weren’t Willie Mays, the Mets have now opted to retire numbers to commemorate the careers and contributions of six of them (with the understanding that revered manager Gil Hodges wore 14 as a Mets player, too). This implies the Mets have retired one number for a little more than every 200 players who’s donned the orange and blue, which is to say that of every 200 or so Mets who come along, the organization recognizes one as incredibly special in the sweep of its history.

Two, 41 and 36, belong to the one-two pitching punch that made that first world championship banner and so much more possible…plus 41 is a category of its own in a Metsian context.

One, 31, belongs to the singular icon of his very if not ultimately successful Met age.

One, 17, is a flag planted in the lunar soil on behalf of the greatest of Met eras, and it was right that 17 was affixed to the rafters first among Mets of his generation, for it was Keith Hernandez who led the Mets’ mid-1980s expedition to the moon and the stars.

But that crew didn’t get there just from its captain’s savvy, clutchness and ability to corral everything hit to him around first base. The 1986 (and 1985 and 1984) Mets revolved around Darryl Strawberry coming of age and Dwight Gooden arriving almost fully formed and the two of them getting us to look up, up and sometimes away. Their numbers, 18 and 16, are going to be up there now.

I’ll look; and I’ll look back on looking ahead; and I’ll look back again, and I’ll love what I see for what I saw when the sky was their limit. ’Cause, y’know, they reached it for us plenty.