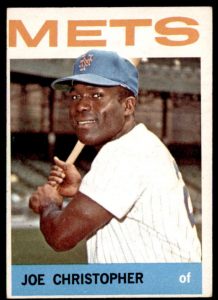

The scouting report I have cobbled together regarding Joe Christopher’s New York Mets career of 1962 through 1965 is he could run pretty well; he could hit pretty well; fielding was optional; and none of it much mattered, because to those who fell hard for the early Mets, Joe’s most outstanding tool was personality. Anecdotal evidence suggests it was off the charts. I wasn’t a first-hand witness, but I don’t think I’ve come across any player from the New Breed days whose name more often elicits a response of “he was my favorite.”

Joe, the first ballplayer from the Virgin Islands to make what for many years we called without qualification the majors, died this past Tuesday, October 3, a helluva baseball date in general and the 58th anniversary of his final game as a New York Met. Joe might have appreciated the connection, given his interest in numerology. That bromide about a ballplayer dying twice, the first time when he’s done playing, doesn’t quite fit here, because Christopher would get some playing time with the Red Sox the next season and keep going in the minor league for a little while thereafter, but the best part of his baseball life ended with his trade to Boston. That is not a provincial inference. Joe said as much in his farewell letter to George Weiss once the right fielder was shipped north in exchange for shortstop Eddie Bressoud.

Christopher made a habit of corresponding with the front office every offseason, even if all Weiss and his staff were looking for in the mail was a signed contract. One of his letters, when he was seeking a raise, ran nine pages (he’d have fit in well had he tried his hand at the blogging medium). He was briefer at the end of 1965, concluding a couple of paragraphs expressing his appreciation for his tenure as a Met by telling the club president, “The four years I did spend with the Mets’ organization were the four most glorious years I ever did spend in baseball. I also want to thank you, Mr. Weiss, for having confidence in me. It made me have confidence within myself.”

And if that doesn’t get you, the postscript will: “It still hurts not to be a Met.”

The fifth pick the Mets made in the 1961 expansion draft — right after Gus Bell, right before Felix Mantilla — Joe Christopher wasn’t exactly an Original Met if you’re a stickler for defining Original as someone on the Opening Day 28-man roster, but he’d be along eventually. Though he’d been a member of the 1960 world champion Pittsburgh Pirates, having roomed with fellow Caribbean native Roberto Clemente during their pennant-winning campaign, the 26-year-old was sent to Syracuse to start 1962. But by May, once Bell was identified as the player to be named later in the trade that brought Frank Thomas to the Mets from the Braves (never mind that Bell had played alongside Thomas for more than a month as a Met), Christopher was promoted to the bigs. The Mets employed 45 players in 1962. Joe was the 35th to debut, on May 21. Ten are still with us. They’re all Originals in their own right.

Christopher showed up literally the day the competitive aspect of the year began to go altogether down the tubes for the 1962 Mets. That trajectory should not be attributed to Joe’s presence. It was a team effort. On May 20, the Mets had swept a doubleheader in Milwaukee to complete a 12-10 stretch that had elevated the Mets into eighth place with a 12-19 record overall, a splendid recovery from their 0-9 start; they haven’t been as close to reaching .500 as a franchise since. Then, after leaving Bell behind at County Stadium as delayed payment for Thomas, they prepared to fly south to Houston and maybe even greater heights in the standings.

This was the legendary night into morning when a) the charter aircraft the Mets were supposed to board in Milwaukee was put on the DL with engine trouble; b) United Airlines entertained the Mets with a cocktail party at the airport until they could roll a new plane in, which didn’t happen until around midnight; c) the flight to Houston had to be diverted to Dallas in deference to heavy fog; d) the team arrived at its hotel in Houston at 8 AM; and e) Casey Stengel instructed traveling secretary Lou Niss that, “If any of my writers come looking for me, tell them I’m being embalmed.”

As were the Mets. Starting that night in Houston, the Mets took off on a 17-game losing streak, coinciding with Joe Christopher’s first official appearance in a New York Mets uniform. The road trip that commenced in Wisconsin and wound through Texas and California represented quite a welcome for the outfielder, who was finding out what made his new team so gosh darn Original.

In his first game, Joe doubled, moved up to third on a wild pitch and was stranded there in the eighth as the Mets lost by one to the Colt .45s. The Mets were 12-20.

In his second game, momentum turned on a deep fly ball that, per Dick Young in the Daily News, “speedy Joe Christopher sprinted obliquely for”; it “shot up his glove and made contact — only to have it pop out of the pocket for a triple” that scored the difference-making runs in a 3-2 defeat. The Mets were 12-21.

In his third game, at Dodger Stadium, Christopher drove in his first run and was thrown out in his first stolen base attempt. The Mets lost, 3-2, and fell to 12-22

In his sixth game, Joe hit his first Met home run, off future Hall of Famer Gaylord Perry of the Giants, tying the game in the sixth. The Mets lost, 6-5 in ten on Willie Mays’s home run off Jay Hook. The Mets were now 12-25.

In his seventh game, Joe inadvertently launched the Mets into their first on-field fracas, getting clipped in the batting helmet while running between first and second as Orlando Cepeda attempted to complete a double play. Joe had to leave the game, but the Mets were already feeling chippy and one of their teammates going down only incensed them further. Soon enough, Roger Craig was drilling Cepeda, Cepeda was jawing at Craig, Craig was trying to pick Cepeda off first, then Willie Mays off second (because what would a Mets-Giants game be in 1962 without Willie Mays on base?), which led to a hard slide by Mays into shortstop Elio Chacon, who wasn’t pleased. Chacon went after Mays, Cepeda went after Craig, and the Giants won by six despite the Mets’ feistiness. The Mets, “outclassed but not outfought,” wrote Young, were 12-26.

Christopher would be back in the lineup a few days later, collecting three hits and scoring two runs against the Dodgers in the erstwhile Brooklynites’ first return to New York; Dem Bums won, 13-6, in the opener of a doubleheader to which none other than Roger Angell, reporting from Manhattan that Memorial Day, traced the birth of the chant “Let’s Go Mets!” The chant lives on today. The losing streak extended through the nightcap and then some, until the Mets’ record plunged to 12-36. Joe would not be a part of a winning effort until June 8, 18 days after his first game. His batting average was .193 by then. It would be up to .244 — with eleven speedy base thefts — by year’s end, indicating a pretty decent surge for player on a team whose results were legendarily indecent.

But the 1962 Mets weren’t about results. They were about legend, and Joe was in the middle of one its most enduring. That story, authentic or embellished, about Richie Ashburn learning to shout “¡Yo la tengo!” so the Spanish-speaking Chacon at short would know Ashburn in center was calling him off a fly ball…only to have monolingual left fielder Thomas trample Ashburn because nobody thought to inform Thomas what was Spanish for “I got it!” was facilitated by Joe, a veteran of Puerto Rican winter ball, serving as Richie’s second-language tutor. “¡Yo la tengo!”, as legend (and band), has outlasted even that 17-game losing streak as a going concern. It’s been around almost as long as “Let’s Go Mets!”

Of all the principles in the YLT tale, Christopher lasted longest as a Met. He survived the Polo Grounds’ closing in 1963 and was planted in right field for the Mets’ first-ever win in the borough of Queens on April 19, 1964, contributing two hits and two runs in support of Al Jackson’s shutout of visiting Pittsburgh. Joe’s talent for getting things going and making things happen continued unabated. The Mets might have been succumbing to one of their usual defeats to close out May 31’s Shea doubleheader versus the Giants, when Joe took it upon himself to belt a two-out, game-tying, three-run homer in the bottom of the seventh. Thanks primarily to his knotting things up, there’d be 16 more innings that day, adding up to 23 for the game and 32 for the day. The Mets would turn a triple play in the fourteenth. Mays would fill in at shortstop. Perry went ten for the ultimate San Fran victory. Larry Bearnarth held the fort for seven innings in relief, in advance of Galen Cisco going the final nine in defeat. Of course there was defeat. These were the Mets. They weren’t good, but they weren’t boring. Ed Kranepool, then freshly recalled from the minors, still tells the story of playing all 32 innings following his having played a full doubleheader for Triple-A Buffalo the day before.

Joe Christopher, however, didn’t make his 1964 only about being anecdotal and incidental on behalf of a ballclub whose play often seemed accidental. A student of both hitting and history — the man soaked up a how-to booklet by Paul Waner and may have been the only Met to recognize irascible 1962 coach Rogers Hornsby as an honest-to-god resource — he boned up and started addressing the ball with authority. He was hitting over .300 until mid-June, took a dip in the average department at midseason, then recovered in a big way. In one of the better Met weeks of the 1964 season, during the same August series when rookie Dennis Ribant burst upon the scene with a ten-strikeout shutout of the Pirates, Joe went wild versus his old team: a double, a homer and two triples in a 7-3 win before the home folks, fans who withstood a rainy night to stand and applaud Joe’s exploits. The dozen total bases set a team record, one of the few that wasn’t related to prodigious amounts of losing. Joe’s bat placed the Mets square in the middle of a five-game winning streak that even Johnny Carson acknowledged in his monologue once it reached four. That’s what big news it was for the Mets to not lose for a few days.

The Mets were 40-82 when they cooled off, and the laughs reverted to being back on them, but Joe kept up his hot hitting for most of the rest of 1964. On the final day of the season, when the Mets were trying their best to play spoiler in St. Louis, Joe laid down a bunt for a base hit that made certain he’d go into the books with .300 average that looked plenty sleek alongside his 16 home runs and 76 runs batted in. Nobody knew what an OPS+ was in 1964, but Joe’s was 135. For context’s sake, that ballpark-adjusted combination of on-base percentage plus slugging percentage to express how good a batter is versus the league average was higher than anybody’s on the zillion-dollar 2023 New York Mets. As was, no everyday Met topped it in the Mets’ first six seasons, and no other Met produced a markedly better all-around traditional stat line prior to 1969.

For one year, Joe Christopher was an offensive force. For four years, the other side of the game, like that triple in Houston back in ’62, more or less eluded him. Pitcher Tracy Stallard went so far as to complain to reporters about Joe’s defense in the midst of his right fielder’s banner batting season, albeit after a misplay on Christopher’s part doomed one of Stallard’s July starts: “Christopher is the only .300 hitter I have ever seen who hurts a ballclub. He improved his hitting this spring. He should have worked on his fielding, too.” That’s some rough criticism (Tracy softened it after Joe’s big game versus the Buccos by allowing “he’s doing better”), but as the years went by, a chorus of Met teammates backed up Stallard’s assertion when asked.

Bill Wakefield: “Joe had a little trouble in the field.”

Bobby Klaus: “He got to a lot of them, and a lot of them he didn’t get to.”

Gary Kroll: “He was a good hitter, but he couldn’t field worth a damn.”

Ron Hunt: “God, he was terrible in the field.”

Yet Joe Christopher, who did not repeat his hitting exploits in 1965, maintained a place in the heart of Mets fans for decades to come. They remembered the base hits, yes, and might not have forgotten the catches that didn’t come to fruition, but what stayed with them the most was the sincere smile and heartfelt engagement of a Met who didn’t put himself above the crowd. The right fielder bridged the distance between his position and the adjacent stands with a stream of back-and-forth chatter (hopefully between pitches). Everybody, it seems, also remembers the ears, the most famous pair of ears in Mets history, at least until Joe Musgrove’s appeared suspiciously shiny on the Citi Field mound as the 2022 playoffs were ending ignominiously.

“When fans in right field cheer Joe Christopher as he trots to his position after a clutch hit or running catch,” Dick Young advised readers of the Sporting News as 1964 wound down, “Christo wriggles his ears for them. This makes his cap quiver, and the New Breed roars with delight.” Joe Donnelly in Newsday wrote, “He wiggles his ears and his cap tips without a hand going to his head.” Whether it was a wriggle, a wiggle or a waggle, it left an impression. All of it did, whether it was fan or reporter taking in what Joe had to offer. In 2017, George Vecsey recalled Christopher as “one of my favorite players in those first loopy years of the Mets,” someone who “talked of spirituality and art and would whisper to writers he trusted, ‘I’m a better ballplayer than you guys think I am.’”

Joe lived to be 87. It’s still great that he was a Met.

One of my favorite Mets. I was at the 32 inning Shea doubleheader with my dad in 1964.All of it. Noon till midnite! One of my best childhood memories. RIP Joe.

Right field in 1964 was my go-to destination at Shea. It was a mutual affection society out there. Thanks for the memories, Joe.

Right field in 1964 was my go-to destination at Shea. It was a mutual affection society out there. Thanks for the memories, Greg.

Joe Christopher and the 1962-65 Mets are before my time as a Mets fan, and pre-Seaver Mets history is shrouded in myth and mystery for me, which is why I appreciate posts like this.

This is the current post, so I’ll put this here:

The go**amned Phillies. Again.

I’m more PO’ed at the Braves. I mean, come on — really? The “juggernaut” Braves? They are perennial post-season chokers.