Atop the annals of below-the-surface New York Mets history — that place where the significance of 1969 and 1986 and Mike Piazza’s home run on September 21, 2001, are implicit — The Rob Gardner Game has long lurked. The Rob Gardner Game may be NYMIYKYK incarnate. If you know, you know. Yet it isn’t something everybody knows. If you don’t know, you’re hardly alone. A few weeks ago, on the National League Town podcast, I referred to The Rob Gardner Game in the context of the eight Mets games that have ended without a winner or loser (when we weren’t sure what was going to become of the suspended Mets-Marlins game of September 28), and I received a social media response from someone who said he’d never heard of the game nor the pitcher…and to subconsciously authenticate the comment, this Mets fan referred to the pitcher as Ron Gardner.

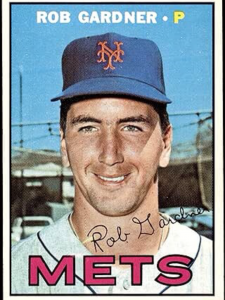

Given that Rob Gardner, who died two Saturdays ago at age 78, hadn’t pitched for the Mets since 1966, or anybody in the majors since 1973, it’s understandable that his name and his feat would be enveloped in the unknown among future generations. His name doesn’t come up very often, and his feat is so unapproachable in modern starting pitching that it takes unusual circumstances to summon it above the surface. If a Met has a perfect game going, you’d probably mention Seaver and Jimmy Qualls or maybe Matt Harvey and his bloody nose. If a Met is threatening to strike out ten consecutive batters or approaching as many as nineteen in nine innings, the names Seaver and Cone are going to cross your mind, lips and, if your phone is readily available, fingertips. Even a tidy shutout might usher the above into your head.

It would be more difficult to organically start thinking about The Rob Gardner Game because nobody’s come close to doing anything like it since The Rob Gardner Game.

Feats and names like those referenced above are the sunniest side of Amazin’, whereas If You Know It, You Know It pretty much transcends or perhaps eludes what we think of as Amazin’. There’s no formula for this, but it’s been my experience as a student and consumer of Mets history that in the best moments of the Mets, when our boys surge from behind with the odds stacked against them, that’s what we call Amazin’! In the lesser moments of the Mets, when our lads somehow find a way to lose when you can’t imagine anybody else would, well, that’s more or less what Casey Stengel meant the first time he called us Amazin’.

The Mets have been Amazin’ in victory and the Mets have been Amazin’ in defeat. But to do what Rob Gardner did and for the Mets — Rob included, but not limited to Rob — to come away with nothing more than a no-decision?

That would seem to be something else altogether.

On October 2, 1965, the Mets hosted the Phillies in a Saturday twi-night doubleheader necessitated by rain Friday night. The doubleheader was necessary, as far as completing the schedule went. Why it had to be a twi-nighter isn’t clear, as the Saturday game was initially scheduled in the neighborhood of 2 PM. Perhaps Shea’s notorious outfield puddles needed the extra three-and-a-half hours to drain. But this was the era when games went quickly, even without a pitch timer. Starting Game One a little after 5:30 might have fouled up some moviegoing plans, but otherwise, what was the harm in making it a twi-nighter?

Game One proceeded swiftly enough, over in 2:31, with a result common to the 1965 Mets, a 6-0 loss at the hands of Jim Bunning, who deserves a digression, even if we are paying tribute to Rob Gardner and The Rob Gardner Game. Bunning allowed three baserunners — singles to Ron Hunt in the first and Bud Harrelson in the sixth, a walk in the second to Johnny Lewis — in going nine, or three more than he allowed in the opener of another doubleheader at Shea the season before. He won that game, 6-0, too. Jim’s effort from June 21, 1964, was a perfect game, so it’s remembered a little more than this one. Actually, almost every time Bunning faced the Mets in 1964 and 1965, it was either a harbinger or an echo of what is indisputably The Jim Bunning Game, when it wasn’t that very game.

04/15/1964 @ PHI: 9 IP; Phillies 4 Mets 1 (7 H, 3 BB, 1 HBP, 11 SO)

06/13/1964 @ PHI: 9 IP; Phillies 8 Mets 2 (5 H, 0 BB, 4 SO)

06/21/1964 @ NYM: 9 IP; Phillies 6 Mets 0 (0 H, 0 BB, 10 SO)

08/09/1964 @ PHI: 9 IP; Phillies 6 Mets 0 (5 H, 0 BB, 6 SO)

08/14/1964 @ NYM: 9 IP; Phillies 6 Mets 1 (5 H, 2 BB, 7 SO)

05/05/1965 @ NYM: 9 IP; Phillies 1 Mets 0 (4 H, 0 BB, 5 SO)

05/24/1965 @ PHI: 5 IP; Mets 6 Phillies 2 (7 H, 2 BB, 7 SO)

07/24/1965 @ NYM: 9 IP; Phillies 5 Mets 1 (2 H, 1 BB, 12 SO)

08/01/1965 @ PHI: 7 IP; Phillies 3 Mets 2 (5 H, 0 BB, 8 SO)

10/02/1965 @ NYM: 9 IP; Phillies 6 Mets 0 (2 H, 1 BB, 10 SO)

That’s ten starts in two years, a 9-1 record with eight complete game victories, four of them shutouts, four of them of registering double-digit strikeouts and one of them the epitome of perfection. Conclusion: Bunning, eventually elected to the Hall of Fame, didn’t need to be perfect when he pitched against the Mets. He just had to pitch against the Mets.

And on October 2, 1965, just as on June 21, 1964, the Mets had to return to the diamond and play a whole other ballgame.

Game Two actually went more swiftly on a minutes-per-inning basis than Game One. Each inning of Game One took a little more than sixteen-and-a-half minutes to navigate. In Game Two, the innings averaged out at shade under 15 minutes. Had you a babysitter on the clock or were worried about rising early Sunday morning for reasons sectarian or otherwise, this would indicate you were in decent shape, even with Game Two starting toward 8:30 PM.

Only problem was Game Two would encompass twice as many innings as Game One. Neither starter, Chris Short for the Phillies nor Rob Gardner for the Mets, was throwing a classic Bunning, but they each kept pace with Jim’s Game One performance.

And then some.

The Phillies blogger version of this story might refer to our contest of interest as The Chris Short Game, except Chris Short Games were numerous in a career that spanned 1959 to 1973, every season except the last one spent with Philadelphia. The lefty posted between 17 and 20 wins four times in a five-year span and made two All-Star teams. Manager Gene Mauch relied on Short and Bunning to carry the Phillies to the 1964 pennant, which proved too much of a burden for the team that was collapsing all around them. The duo started ten of the final fifteen games those Phillies played — five apiece. Short went on rest that mirrored his last name: two starts with only two days’ rest, the other three on the then more common three days’ rest. It was crunch time, and Mauch wasn’t messing around. Except crunch time devoured the pair of pooped pitchers at season’s end, and the 1964 pennant wound up flying over St. Louis.

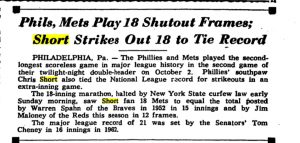

Still, 301 starts as a Phillie, with 132 wins and 24 shutouts, enough to earn him 1992 induction onto the Phillies Wall of Fame. Lots of candidates within such a portfolio for The Chris Short Game, you’d figure. But could you do better than 15 shutout innings punctuated by 18 strikeouts, or as many as any National Leaguer had ever struck out in an extra-inning affair to that point? With no vested interest in Chris Short’s story (one that sadly ended when he was 53 years old in 1991), I’d have to think that would qualify quite nicely as The Chris Short Game.

Those totals were accumulated in the nightcap of October 2, 1965. Fifteen innings pitched. No runs allowed, with nine Met hits and three Met walks scattered. Eighteen Met batters struck out. Yikes.

But let’s toss the “yikes” into the visitors’ dugout so we can see how they look on the other foot, because Chris Short’s Phillies did nothing to support him. They, too, faced a starting pitcher for fifteen innings — a rookie, no less, though a rookie who had once thrown sixteen innings in a minor-league start — and they, too, didn’t score. Five hits and two walks, but no runs. They didn’t strike out quite so often (only seven times), but the bottom line was the same.

Where it mattered, on Shea Stadium’s massive scoreboard, the Phillies couldn’t touch Rob Gardner. Of course they couldn’t, because the nightcap of the Mets-Phillies doubleheader of October 2, 1965, was The Rob Gardner Game.

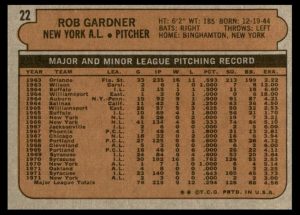

Let us be clear that Rob Gardner had other good games in his Met career, including two route-going wins the following May, 2-1 over the Cubs and 6-1 over the Giants. Also, Rob enjoyed a very solid season in a New York uniform in the next decade, even if it wasn’t what we’d consider the most desirable New York uniform. The southpaw came up to the majors on September 1, 1965, the day before the Mets retired Casey Stengel’s number, and lasted, as a Milwaukee Brewer until July 13, 1973, by which time pitchers in that league were no longer encouraged to hit for themselves (which, in Rob’s case, might have been for the best, as he represented four of Short’s eighteen strikeouts). He didn’t stick on any one roster for all that long, but he stuck around in general. The Oakland A’s, while they were in the process of winning three consecutive division titles, thought enough of Rob to acquire him three separate times. Gardner’s ledger shows 109 games pitched altogether, starting and relieving.

But only one could possibly be The Rob Gardner Game. If the TRGG’s calling card was merely 15 innings — endurance matched by only one other Met pitcher, Al Jackson in 1962 — that would likely be enough. If TRGG’s credentials were simply embellished by the fact that the 15 innings translated to 15 zeroes, so many that you know Shea’s “Stadiarama” technology, however breakthrough it was considered when it debuted, couldn’t display them all that once, that would be more than enough. No other Met has thrown fifteen shutout innings in one game (Little Al in ’62 was nicked for a run in the fifth and gave up two to take the loss in the fifteenth). What makes The Rob Gardner Game The Rob Gardner Game is its resolution.

There was none. Certainly not for the starting pitchers there wasn’t. Short threw fifteen scoreless innings. Gardner threw fifteen scoreless innings. Short got a no-decision. Gardner got a no-decision.

Everybody got a no-decision.

Picture Oprah Winfrey telling each of however many among the paid attendance of 10,371 who remained as the teens kept piling up to look under their seats. “You get a no-decision! You get a no-decision!” Same for those sitting in the dugouts or the bullpen, same for those standing at their positions. For as swiftly as those innings were going on a minutes-per-frame basis, there were a lot of innings. Extra innings, obviously, not to mention the hours that entailed: four full, plus almost half of another. By October 2, 1965, Mets history was already informed by how long it could take this team to play and usually lose some games, most notably the one from the end of May in 1964, also the nightcap of a doubleheader. That’s the one that went 23 innings and 7:23 on wristwatches. Except that had lots of scoring — Giants 8 Mets 6 — along with lots of anecdotes (the Mets turned a triple play; Willie Mays played shortstop; What’s My Line? referenced it live on the air, flipping many a channel in the Metropolitan area from 2 to 9) and, most importantly regarding its conclusion, it started on a Sunday afternoon, far earlier than the first pitch Gardner threw to commence the nightcap action on what could no longer be called Saturday evening. Blue Laws lingered on the books in 1965. You could play late into the night any night as far as the National League was concerned by then, what with NL curfews having been done away with after 1964, but heaven forefend you start an inning as 1:00 AM closed in and Saturday night became Sunday morning in New York. Then again, with Saturday games usually executed in the afternoon and most games proceeding with alacrity, how often was that likely to come up?

It came up on what was now October 3, 1965. Over the succeeding three innings following the respective departures of the starting pitchers, the relievers who succeeded Short and Gardner — Gary Wagner and Jack Baldschun for the Phils, Darrell Sutherland and Dennis Ribant for the Mets — kept the zeroes coming. That’s how we got through eighteen innings of total shutout ball. That’s how, with the Longines clock atop Shea’s scoreboard ticking relentlessly, 0-0 got called a tie. They didn’t suspend games of this nature then. They declared the game happened individually — with the stats of Gardner, Short and all those flailing batters going into the books — but not in the standings. No sense picking up a game with zero pennant implications the next day, the final day of the season, in the nineteenth inning.

Nor was there any sense in doing what they used to do with ties and playing it over from scratch. But they did, anyway. It, like everybody being told to go home from a gathering at Shea Stadium before 1:00 AM on a Sunday, was the rule, so it was followed to the letter. The weary second-division finishers had to do a little extra finishing on Closing Day and play a doubleheader in daylight on October 3. The Mets lost both games, both by scores of 3-1. The second game went thirteen innings. Jack Fisher pitched all thirteen, the third-longest outing by any Met pitcher ever. Al Jackson, who pitched fifteen innings in a losing cause in 1962, started the opener and lost, going eight-and-a-third (piker). Jack, like starter Larry Bearnarth in Saturday’s opener versus Bunning, was beaten by a future Hall of Famer, Fergie Jenkins, who pitched two innings of relief. It was Jenkins’s second major league win and his last as a Phllie; he’d be traded to the Cubs come April. Fisher’s final record for 1965: 8-24. Jackson’s: 8-20, his “you have to be pretty good to lose 20 games…” mark clinched in the doubleheader. It was the last time one National League staff harbored a pair of twenty-game losers and there they were, losing on the same day, the final day of the season.

Fisher’s and Jackson’s hard-luck exploits on top of Gardner’s should have made great or at least acrid copy in the New York papers, except the New York papers were on strike. The Philly press, in whatever space wasn’t given over to the Iggles by Monday, was understandably more interested in the visitors’ angle — Gene Mauch denied the Phils were, as Stan Hochman in the Philadelphia Daily News termed them, “a pack of malcontents” — though there was a day-after quote from Bunning, reflecting on the callow competition he and his staffmates dominated all weekend. “What are they doing,” Jim asked of the Mets brass’s thinking, “rushing those kids to the majors?” True enough, Saturday’s and Sunday’s lineups included quite a few representatives of the Youth of America, as Stengel liked to hype them before he and his broken hip gave way to Wes Westrum. Maybe kids named Ed Kranepool, Bud Harrelson, Ron Swoboda and Cleon Jones weren’t yet fully enough formed to take on the Bunnings and Shorts of the National League. Longines’ clock would tick on where they were concerned.

The Mets had tried to bide time with the baseball-elderly in their first season, and lost 120 games. Slowly but surely, youth was coming to define the franchise. Lindsey Nelson, in Backstage at the Mets, a book he published with Al Hirshberg in 1966, tried to dissect the futility he’d witnessed so much of for four seasons and asked, “how do you achieve victory? Where is your future? In the kids, of course, in the Kranepools and the Hunts and the Swobodas and the Napoleons.” Lindsey rattled off more potential comers, “kids like Kevin Collins and Darrel Sutherland and Tug McGraw and Johnny Lewis and Jim Bethke and Dick Selma and Larry Bearnarth and Jerry Hinsley and Ron Locke and Johnny Stephenson and Greg Goossen and a whole crop of others you haven’t heard of yet.”

Presumably, one of the latter cohort was Rob Gardner, as Lindsey, despite his admirable thoroughness, left out the lefty (and Cleon Jones).

Geographically in between New York and Philly, writing for the Record in North Jersey, Gabe Buonaro noted, “The Mets had to play 49 innings in less than 30 hours before realizing they weren’t much better than when they started in 1962.” The perceived progress of climbing from 40 wins the first year to 51 in ’63, then 53 in ’64, was wiped away when the Mets’ 0-3-1 final weekend left them at 50-112 for ’65. The most positive number to come out of the Mets’ fourth season? Home attendance was, as the AP put it, “a highly successful 1,768,387,” better than the year before, when Shea Stadium opened, trailing only the league champion Dodgers and the newly domed Astros in the NL. Shea was absolutely still an attraction, even if the novelty would probably need some Ws to enhance it down the line. As Lindsey advised at the end of his future-leaning chapter, “Keep trying.”

When the Sporting News got a chance to mention what had happened on October 2 & 3, in its October 16 issue, the so-called Bible of Baseball gave the eighteen shutout innings the Mets and Phils played three Short paragraphs, which is to say Chris Short was lauded for tying the NL extra-inning strikeout record, and Rob Gardner went altogether unmentioned.

Given the lack of dedicated on-site coverage of the Mets’ side of the Saturday night tie and the sparse crowd through the turnstile (no doubt lessened as Sunday approached and pay-phone calls to babysitters resulted in early exits), not to mention that a final weekend with no postseason implications tends to not draw focus to begin with, the rarity of an eighteen-inning 0-0 tie in which both starting pitchers went fifteen shutout innings seemed destined to fade into immediate obscurity, a field of zeroes falling in a forest whose trees glistened with the dewdrops of puritanical residue. Baseball’s attention turned to L.A. and Minnesota, where the World Series was about to start up. “Curfew” was accepted as just one of those things that arose. Same for a tie. Today, one imagines, the likes of Sarah Langs, Jayson Stark and Mark Simon would be all over this kind of game, and our contemporary baseball curiosity culture would lap up every extraordinary nugget with an oversized spoon. Then, you either saw the game or leafed past something about it in the Sporting News later in the month.

The Mets in their brief history had played three other ties before October 2, 1965, including one at the end of that May (due to darkness at Wrigley). They happened, as did replays of ties; the system wasn’t any daffier than suspending a game in a rainy first inning on April 11 and picking it up as if five-and-a-half-months hadn’t gone by on August 31, as occurred by MLB fiat with the Mets and Marlins in 2021. It couldn’t have not seemed odd or a little illogical to make these immediately winterbound teams make up the eighteen resolution-deprived innings from Saturday night with an additional nine on top of the nine scheduled for Sunday (which turned out to be thirteen), but 162 is 162, and the Mets and Phillies were on the premises, so a Sunday doubleheader it became in the name of the sanctity of the schedule. But then it was over, and everybody moved on.

All of which is to say what should have been legendary in the most textured sense of the word — people should have been telling stories of the night the recent minor league callup for the perennial last-place ballclub went toe-to-toe with a star pitcher for fifteen innings only to have a rarely invoked calendar-dependent technicality get the best of both of them and their teams — all but disappeared from the Metsian discourse. Bob Murphy, Ralph Kiner and Lindsey Nelson were marvelous in bringing me up to speed on all the charisma and color and hijinks of the Mets I missed before tuning into this franchise in 1969, especially that 23-inning game from 1964 and the doubleheader it was a part of, but I don’t ever remember them filling time between pitches with recollections of that night at the end of the 1965 season when Rob Gardner did something no other Met had done. Lindsey had a good excuse — he called Notre Dame games on Saturdays in the fall and was in South Bend, which may also explain why he omitted Rob from his Youth of America roll call in 1966. Maybe the fact that their newspaper compadres weren’t on the job in early October ’65 to bring it up to Bob and Ralph in some random pregame press room chit-chat (“hey, Murph, remember that night when that kid went fifteen and they called it a tie?”) cut the legs off the tale. It seemed to miss all the post-’69 team histories I read growing up, probably because those tended to be written by the beat reporters who were remembering what they saw, and having been on strike that weekend, they didn’t see it.

Thus, the basic qualities of Amazin’ eluded The Rob Gardner Game. It wasn’t an unlikely win that would draw a hearty hand clap when its particulars were rolled out yet again. It wasn’t a mind-boggling loss over which you could only shake your head and chuckle ruefully/knowingly about how those Mets could be. It was a tie that didn’t get sufficiently chronicled and wouldn’t be batted around in the years to come. The Mets’ record in 1965 should be expressed properly as 50-112-2. Yet when was the last time you heard a baseball record carried out to a third column?

Me, I’m almost certain I had no idea this game existed for the longest time, even though I knew who Rob Gardner was when I was a kid. When I was a kid, Rob Gardner was a Yankee. I knew that because he was having a pretty good go of things in the Bronx. Not that I was in favor of that, but it was what it was. Gardner’s best year in the majors was 1972: fourteen starts, eight wins, a hand in helping the Yankees to legitimate contention (something else I wasn’t in favor of). That was the year I got my first Rob Gardner baseball card. I’m pretty sure I got several that year. One day I turned one of them over and examined Rob’s stats. For 1965 and 1966, he was listed as a member of New York, but the league then was “N.L.”. Son of a gun, I thought, this guy was a Met. I experienced that sensation once in a while in my formative years. I’d get a Bob Johnson (either Bob Johnson), a Larry Stahl, a Don Shaw and notice New York N.L. in their past. Who knew? Not me. There must have been more Mets way back when than our announcers talked about these days was my conclusion.

Had Topps not opted to fill out Gardner’s stats with his many minor league stops, I might have learned about his fifteen-inning virtuoso performance from seven years before, but there was no biographical info beyond height, weight and birthdate, how he threw, how he batted, and his home being Binghamton. A kid handling card No. 22 in the first series of 1972 was left to deduce that if they were showing you minor league records from 1963 forward — which included time at Syracuse in 1971, because Gardner still hadn’t truly established himself in the majors — there must not be much more to tell.

Had I had Gardner’s 1967 card, like I had Chris Short’s, I might have retained the salient details of his career to date:

Rob is one of the bright young pitchers in the New York Mets’ organization. The smooth throwing southpaw holds the club record along with Al Jackson for most innings pitched in one game. Rob accomplished this feat by hurling fifteen scoreless innings against the Phillies on the next to the last day of the season in 1965. Watch him go in 1967.

Though Topps left out the part about the tie, they couldn’t have been more on point. In Dick Young’s not yet jaundiced view, Rob was right up there among the “young pitchers who made Alvin Jackson expendable” when the Mets traded for Ken Boyer in the offseason following ’65, namechecking him in the same up-and-comers list that included Tug McGraw and Dick Selma. By May of ’66, Barney Kremenko was celebrating Rob in the Sporting News for his self-taught curveball, noting the fifteen-inning performance from the previous October “gave him extra status when he reported in camp for spring training. Before his performance against the Phillies, Rob was just another young pitcher in the Mets’ organization.” The upshot of Gardner’s foothold in the bigs was at least he, his wife and their baby could lease an apartment in New York this year without worrying about getting sent back to the minors.

Ah, but Topps saw what was coming, for even though Gardner’s breaking stuff helped him to those complete game wins in May, the rest of the season didn’t go all that well, and in 1967, Mets fans did watch him go. He was traded to the Cubs for another lefty, Bob Hendley. As they crossed agate-type paths, perhaps the portsiders compared notes on what it was like to pick the wrong night to throw the respective game of his life. You think Gardner was overshadowed by Short’s eighteen strikeouts? On September 9, 1965, Hendley twirled a masterful one-hitter at Dodger Stadium versus the eventual world champions. The only run he gave up was unearned: walk, sac bunt, steal of third, throw got away. His mound opponent? Sandy Koufax. Koufax threw a perfect game. Also going to Chicago as the player to be named later in that deal was Johnny Stephenson, who struck out to end Jim Bunning’s perfect game in 1964.

Irony is swell, but it doesn’t secure leases in major league cities. There’d be a lot of bouncing between the majors and the minors for Rob Gardner between 1967 and 1975. The solid ’72 with the Yankees made him attractive anew to Charlie Finley in Oakland. Finley liked to wheel and deal, and Rob got caught up in a trio of green-and-gold transactions. Once he was traded for Felipe Alou. Another time, he was traded for Matty Alou. How he was never exchanged for Jesus Alou is almost as big a mystery as the 0-0 tie of October 2, 1965. No more astounding performance in Mets history feels as shrouded in as much fog as The Rob Gardner Game. Contemporary accounts are few, vague and terse. Footage isn’t in evidence. It may have earned the pitcher in the home uniform “extra status” when it came to a fleeting leg up on a full-time role the next season, but even the man himself didn’t remember how it all went down until he was reminded of it.

In 2020, with the pandemic demanding creativity from idling baseball writers, Hannah Keyser, then with Yahoo! Sports, reached out to Gardner, 75 at the time, to explore the game as in-depth as possible from the vantage point of nearly 55 years later. “You’ve probably never heard the story of the best pitching performance in Mets history” was the headline. It’s an engaging article, highlighted by…

a) Rookie Swoboda recalling he left the stadium to dine at nearby Lum’s with his parents once he was ejected for arguing balls and strikes in the first inning of the nightcap, and then, after a leisurely dinner, noticing the lights were still on at Shea (“I wasn’t supposed to leave,” he found out the next day).

b) Gardner’s opposite number Short going as long as he did because, per scuttlebutt Rob heard later, Chris insisted to Mauch, “I’m not coming out until that other son of a bitch comes out.”

c) The protagonist of the story not knowing until Keyser reminded him that the game was a tie that was started over from scratch the next day. He sort of remembered it resuming from where it was called for the curfew, but nope, it wasn’t. Then again, like Swoboda on Saturday, Gardner had left the ballpark. Since Westrum wasn’t going to use him on Sunday, he and his wife got an early start on their drive home to Binghamton.

“That means that game never existed,” is how Rob in 2020 processed his fifteen innings of superlative effort.

But of course it existed. Individual stats always existed in ties. And, though I understood what the headline writer at Yahoo! was going for, I resented slightly the implication that I had never heard of this pitching performance. By 2020, I was well-versed in the topline details of what had happened on October 2 into October 3, 1965. Thing is, I have to admit, I’m not sure when I first heard of it. As it wasn’t one of those legends that seeped into my consciousness through the courtesy of Bob, Ralph and Lindsey, it wasn’t “always” a part of my Mets knowledge base. I likely learned of its existence sometime after 2000, long after I put aside that 1972 Gardner card, once Baseball-Reference came into being. Before Baseball-Reference (and its essential and still extant forerunner Retrosheet), if you didn’t quite remember something, you either started combing your baseball library or planned a visit to your public library. Mostly you remembered murky details as best you could and went around unaware of everything else you never heard of.

If I stumbled into The Rob Gardner Game, I’m guessing it was in service to looking up Game Scores on Baseball-Reference. I learned what a Game Score was shortly after we began blogging here in 2005. It’s a Bill James-devised metric meant to deliver a thumbnail sketch of a starting pitcher’s effectiveness in a given outing:

50 point baseline

1 point added for each out/3 points for each complete inning

2 points added for each inning completed after the fourth

1 point added for each strikeout recorded

2 points subtracted for each hit allowed

4 points subtracted for each earned run allowed

2 points subtracted for each unearned run allowed

1 point subtracted for each walk issued

You recognize a superbly pitched game when you see it, whether you’ve actually seen it or just read the box score, but Game Score was a way to quantify it, and what baseball fan doesn’t want a digestible number to bandy about for comparing and contrasting purposes? In the mid-2000s, I may have been looking up best Mets Game Scores because of something Pedro Martinez had done in the present, or out of curiosity for something Tom Seaver or David Cone had done in the past, but when I got there, one name topped them all: Rob Gardner. Rob Gardner’s Game Score of 112 on October 2, 1965, was and remains the top Game Score in Mets history, six points better than the runner-up, Seaver in a twelve-inning no-decision en route to a fourteen-inning Mets loss in 1974, and thirteen points better than Cone, who set the nine-inning record when he struck out nineteen Phillies on Closing Day 1991 (as the cops waited to talk to him). Pedro, incidentally, posted his highest Met Game Score, 90, when he flirted with a no-hitter in June of ’05. Not so incidentally, Chris Short’s Game Score from The Rob Gardner Game was 114.

Like I said, I think this was when I first learned of Gardner’s night of brilliance. Or I kind of knew it, but the metric cemented it enough that in the years to follow, I’d casually drop it into conversation on an IYKYK basis, confident that whoever I was talking to it knew. For example, I was fully aware of it as Jason and I departed Shea on September 27, 2008, the penultimate game at the ol’ ballpark, when Johan Santana blanked the Marlins for nine innings on one knee. We didn’t know he only had one good knee as we watched him shut down Florida. We knew we couldn’t afford to lose in pursuit of a playoff spot as the season (and Shea) were ending the next day, nor could we afford to see the bullpen gate swing open with any 2008 reliever entering, as Jerry Manuel’s circle of trust’s circumference resembled a pinprick. Our breath was taken away by what Johan did, and as we made our way down the ramps, we asked each other if we had just seen the best pitching performance in Mets history. I remember speaking up for The Rob Gardner Game as a candidate, knowing Jason knew what I was talking about. I also remember we sort of hastily dismissed it because on that penultimate Saturday forty-three years earlier, when hitters on both sides might not have been locked in on any pitch as much as they were mentally loading their automobiles and heading home, nothing was really at stake for the 1965 Mets.

Certain moments’ ability to defy quantification represents another reason The Johan Santana Game with its very good if not dazzling Game Score of 87, holds a place of honor alongside The Imperfect Game and The Ten Consecutive Strikeouts Game and The David Cone Game and The Bobby Jones Game in the 2000 playoffs and The Jon Matlack Game in the 1973 playoffs and The Al Leiter Game to get us into the 1999 playoffs and The Nosebleed Game a couple of weeks after The Harvey’s Better Game and some others that don’t require much elaboration above the surface in the annals of New York Mets history where best-pitched games are concerned. And maybe why The Rob Gardner Game has simmered below the surface as a hidden gem, an overlooked classic of the genre.

But if you know from The Rob Gardner Game, you know fifteen scoreless innings — even if the Mets were in tenth place and a tie would be called — rates as good as a Met start gets even if one resists declaring it the absolute best.

And if you didn’t know, now you know.

You should also know that Rob Gardner’s post-baseball life had him returning to Binghamton and becoming a paramedic for the fire department up there and, when he was 56 years old, he joined other firefighters who came down from upstate to Ground Zero to help however they could in the unspeakable aftermath of 9/11. He told Keyser, “Every one of us got involved, in some corner helping somebody dig for something.” Revisiting that 2020 story, which climaxed with Rob revealing, “I felt a lot more relevant as a firefighter than I did as a baseball player,” I thought about how proud we were as Mets fans that our players in 2001 were visiting the site and reaching out to rescue workers trying to find anybody or anything in the rubble, and that the Mets’ presence was said to mean a great deal to those who had lost their brethren. And Piazza’s home run on 9/21, too, which forever sealed the bond between the Mets and those who were doing the heavy lifting. One of those people in the thick of it, however, even if it was for just one day, was a real, live New York Met, not there to lift spirits, but actually lift.

I’m guessing he didn’t tell anybody there who he’d been or what he’d done in 1965.

Just wonderful Greg. I actually do remember the Rob Gardner game, or at least talking about it the next day. In the little kernels of info one somehow retains 58 years later, I remember it was on a local ballfield in Bay Ridge. I don’t think it was an organized game or anything, it would have been too late in the year for that. Probably just a bunch of us teenagers getting together on a Sunday.

Yet my takeaways from your article are:

So it appears Chris Short had to die before getting elected into the Phillies Hall of Fame. I have no idea how many players were in The Phillies Hall of Fame at that point (not that I have any idea how many are in it now either). It could have been 50 or it could have been just Richie Ashburn, Mike Schmidt and maybe Chuck Klein or somebody, but it seems unfair that we wasn’t in it yet when he passed.

And, did I read that right, Gardner had no strikeouts?? Just think of the Game Score it he had managed just 5. Well, I guess it kept his pitch count down.

Thanks again. for this, and 2023 in general.

Thanks for your remembrance, Ken. You’re right about the posthumous induction of Short. I try not to judge how other teams honor their own.

Gardner has seven Ks, noted above.

…Gardner has seven Ks, noted above.

Ah, OK. Thanks. I jumped to a conclusion based on this sentence…

…Those totals were accumulated in the nightcap of October 2, 1965. Fifteen innings pitched. No runs allowed, with nine hits and three walks scattered. Eighteen batters struck out, all of them Mets. Yikes.

Ah, I can see how that might be read and redid that passage. Thanks.

One of your greatest pieces, Greg! The poignancy of the conclusion is masterful, particularly with what’s happening in the world today. And, yes, there was that distant sense of a brighter future with the tentative arrival of those ‘64 “kids”. May our own future, Mets and the world, be as bright.

Thank you, Andy — and amen.

Greg-

Another great piece of Mets History that somehow I still recall.

Can’t remember what I did 45 minutes ago, but I do recall what you wrote about.

Jim Bunning I despised, I only disliked Chris Short.

Thanks for the info-you do know our Mets History!

And yes, I was at that 1964 Memorial Day DH VS Gints with 2nd game going 23 innings and Mays played SS for 7 innings!

We did not stay for entire 2nd game.

Thank you & Jason for your articles.

“Jim Bunning I despised, I only disliked Chris Short.”

If that’s not a Mets fan since 1963 speaking, I don’t know what is. Thank you, Bob.

Thank you!

And so ends THE most boring baseball season in history. Too many Wildcards renders the regular season meaningless, which then leads to rendering the postseason meaningless as well. Which then leads to the least watched WS in history.

No surprise there at all, I’d say.