Welcome to the second installment of MY FAVORITE MET SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT, a continuation of the project I introduced on my birthday. The ten seasons spotlighted below I liked a little more than the dozen I counted down on December 31, not as much as the thirty-three that are still to have their number called.

As we creep out of the shadow of the “LEAST” end zone (forgive the football terminology), I’m sticking with the notion of saying something nice about seasons that weren’t that nice, though this time around being less purely anecdotal and attempting more to identify how their essence meshed with my experience when they were live. Each of these campaigns had something going for them for at least a little while; a couple even ended with winning records. I didn’t find them close to ideal, but there were threads that stay with me that didn’t strangle my Metsian enthusiasm.

This is a personal appraisal. My ranking of a season as “37th-favorite” is neither right nor wrong. It is mine. Some of these capsules lean to the first-person. Some spout numbers as if I were the offspring of two computers. Both forms of expression indicate how I interpret this ballclub. Were the Mets making me feel good in the year in question? Were the Mets actually good in the year in question? The seasons the Mets strove sincerely for success and succeeded to some degree tend to place higher with me. This group of years falls short on that count, yet for a week or a month, I believed they were getting there. Or maybe they were just giving me something I needed to keep going as a Mets fan.

I was gonna keep going, regardless, but a boost in the right direction is always appreciated.

Processing the competitive contours of the 2021 season less than three years after the fact, I find it shocking to remember the Mets were a first-place ballclub from early May to early August. I would say they “commanded” the NL East for three “solid” months, but their lead was gelatinous and their command never more than tenuous. I find it better to forget the false summer of divisional dominance along with the frustration that abounded once it dissipated and recall instead the true purpose of our first full season of baseball since COVID entered the atmosphere. Call 2021 a rehab year for us as fans. Learning how to finish out Spring Training again. Learning how to start a season more or less on time again. Seeing and hearing some people in a ballpark again. Becoming one of them once it felt OK. Remembering what you could and couldn’t bring to a game — and that you might as well keep a mask handy. Willing to almost convince ourselves this Met team might stick around until October. Fuming when the standings finally reflected our doubts. Glad to be done with this season, antsy for the next one. Normality crept back into our routines. We regained the hang of what came naturally…including falling out of the race when it turns out the Mets aren’t really very good.

42. 2004

“That uneasy alliance between Bright Young Things and old survivors” was a phrase spoken in a 2003 film that foresaw what was coming at Shea Stadium the very next year. From Fred Wilpon’s nostalgic haze for the Dodgers emerged a parade of veritable codgers: Franco, Leiter, Gl@v!ne…ten dudes in all born the same decade I was, which was several decades before, and nobody was scouting this veteran of the baseball scene. Seven Mets were older than Mike Piazza, history’s greatest-hitting catcher judged to have gotten so up there in years that he was directed to try his mitt at first base. But for a while, the old guys still had it. Crustiness notwithstanding, the 2004 Mets moved to within one game of first place on July 7. The creaky nature of the operation began to show, and there went both contention and Wilpon’s dream of meaningful games in September, a month when the franchise for a third consecutive season went to seed. Yet there was that bright young Jose Reyes, when his hamstrings were loose, preparing to reclaim shortstop from Kaz Matsui (what was up with that?), and there was that bright young David Wright, once he had enough Triple-A under his belt, getting promoted and driving in runs. I leapt from my seat for mind-boggling home runs from Victor Diaz, 22 (his career first), and Todd Zeile, 39 (his career last), eight days apart. I didn’t know where we were going, but I figured we’d get there eventually.

41. 2012

I’m tempted to say we should have called it a season once Johan Santana made our dreams come true by throwing The First No-Hitter in New York Mets History on June 1, but then we would have missed R.A. Dickey’s incomparable journey to Twenty Wins. I’m tempted to say that we shouldn’t have bothered with anybody’s post-Nohan starts except R.A.’s, but then we would have missed the sizzling batch of innings dropped on our plates by prodigy pitcher Matt Harvey. Well, maybe arrange to consume only the most uplifting starts of Santana’s, Dickey’s and Harvey’s — but then how do you enjoy David Wright’s last full-on MVP-caliber campaign, including the night he broke the franchise hit record? Jeremy Hefner started for us that night, so you kind of had to watch everybody. There were many gobs of good to 2012, even the illusion that 2012 was going to be something beyond the ordinary, and not just because of the occasional à la carte splash. We were seven games over on July 7 before finishing fourteen games under at the close of business on October 3. With the second half came a baseball bout of seasonal affected disorder, a.k.a. SAD. Essentially six days of gray skies per week, then there’d be one day the sun would burst through. Somebody would do something exhilarating or downright historic, we’d high-five across our screens, and then we’d be back to moping. Based on the composition of the roster, you could have forecast that’s how it would go. Still, those days that weren’t dreary made you want to believe Met-eorologists aren’t always accurate.

40. 2011

This team had spunk. Lou Grant might not have approved, but he wasn’t our news director. The news for us as 2011 unfolded was the Mets weren’t nearly as bad as they could have or should have been amid the depths of the Bernie Madoff fallout. They weren’t terrific by any means, nor did we expect them to be. They started the season with Brad Emaus at second base. I try to resist picking on individual players as illustrative of how hopeless the overall situation was in a given year, but I repeat: we started the season with Brad Emaus at second base. Because he was a Rule 5 pick plucked from the Blue Jays, we had to keep Emaus on the active roster or risk losing someone who was supposed to be our offseason bargain. Having gotten off to a 5-13 start, which nobody bargained for, maintaining Brad Emaus emerged as less than a priority and he went back to the Toronto organization before April was over. Terry Collins’s first crew, once Eamusless, began to demonstrate bona fide competence, busting past the .500 barrier for a spell and displaying a knack for now and then capturing games that appeared utterly out of reach. Down 7-0 to the Pirates after two-and-a-half on June 2, the Mets won, 9-8. Down 6-1 to the Cardinals — a team rampaging toward a Wild Card that they would exchange for a world championship — after seven on September 22, the Mets won, 8-6. The season was speckled with Mets Classics that never get reaired as such. If SNY did show them again, would you recognize half the players? Loads of Emauses (Emaii?) made their Met entrances and exits in 2011. Blaine Boyer! Taylor Buchholz! Chin-lung Hu, for whom a question mark would serve as effectively as an exclamation point! Willie Harris, who you likely remember far better as a homer-thieving Met villain than any kind of Met helper, played in 126 games, as many as chronically hamstrung batting champ Jose Reyes (Willie drove in the go-ahead runs in that Cardinal comeback). Jason Pridie, who you likely barely remember if at all, played 101 games — one fewer than David Wright did the year The Captain was first compromised by back issues, and 32 more than he himself played total in snippets of six other seasons for six other teams (Jason drove in the winning run in the game that followed the Pirate comeback). Val Pascucci socked 21 home runs at Buffalo, earning himself a September callup after a seven-year absence from the majors (his one Met homer broke up Cole Hamels’s no-hit bid). This team also had Francisco Rodriguez and Carlos Beltran, guys who are receiving Hall of Fame votes more than a dozen years later, but traded them both in July despite having arrived at the fringes of the playoff race with them in tow. The day Beltran was swapped to San Francisco for minor leaguer Zack Wheeler, we were one game behind St. Louis. We understood the business reasons that dictated shying away from going for it. We understood the 50-38 stretch that erased the Emausosity of our start was mostly a spunky mirage. We understood limping to the finish line well out of the money was inevitable. We can be ridiculously understanding that way.

39. 2013

The blob of non-competitive baseball conducted by undistinguished Mets collectives that filled the years between the dismantling of Shea Stadium and Citi Field’s eligibility to host postseason contests does its best to exist as a blur a decade later. One year’s very like another/when your head’s down over the standings, brother. Yet 2013 stands out clear in the mind’s eye if I squint hard enough…and I do like to squint. The 2013 Mets dealt us multiple nadirs early and late, but there was a stint when they rose to the level of their best pitcher, Matt Harvey, and their best player, David Wright, and their ballpark’s signature attraction to date, the All-Star Game (in which the National League started Wright at third and Harvey on the mound). For a month-plus, surrounding the Midsummer Classic’s first trip to Flushing in 49 years, the world resembled the Mets’ oyster. An array of second-line overachievers played with pep and zip and verve and panache, leaving me believing they weren’t necessarily going to lose every night. Everybody from David Aardsma — who usurped Don Aase’s spot atop the alphabetical cataloguing of the all-time roster — to Eric Young, Jr. — who swiped a stolen bases crown after coming over from Colorado — kicked in a little something. You couldn’t spell Mentos without Mets, and this was our freshmaker period. So what if it lasted not much longer than a mint in your mouth? The 22-14 spurt didn’t erase the dreadful 24-39 stumble out of the gate, and it didn’t prevent a 28-35 fizzle to the finish line, but somewhere in there was a real team to get real excited about.

38. 2018

Thirty days hath September/April, June and…oh, those months of magical, tragical thinking. Going chronologically and allowing ourselves some leeway for a season that started on March 29, we were treated to the best Mets team ever for the first nine, ten, eleven, twelve, thirteen and fourteen games of 2018, accomplishing unheard of Met records like 11-1 and 12-2. The blistering pace couldn’t last, but the Mets were still in first when April ended. Shockingly, they weren’t in last when June was over, though not for lack of trying. The same team that ripped off a record-setting start plummeted from one game above .500 on May 30 to sixteen below exactly one month later. The 5-22 nosedive told us everything we needed to know about who the 2018 Mets were…until September, when an 18-10 end run had us reconsidering. ”Well, if we could just subtract June…” Calculating wins and losses could be a confounding exercise that year. I know for certain I saw Jacob deGrom pitch to a 1.70 ERA across thirty starts, and it was stupendous, yet I also know I saw Jacob deGrom collect 10 Ws against 9 Ls, and that was stupefying.

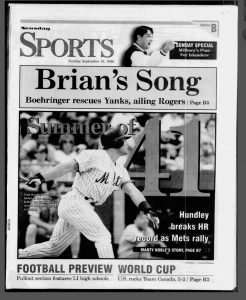

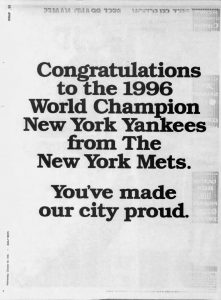

37. 1996

I felt something for this team amid the dregs of September that had been missing from the vast expanse of dismay that turned April through August into such a drag. A whiff of a hint of a clue that better days were ahead for this 91-loss jugger-NOT? Not exactly. The numerical pursuits of Todd Hundley (41 homers) and Lance Johnson (227 hits) certainly kept me leaning forward, but it was also what was going on across town. The Yankees were nearing their first divisional title in fifteen years and taking too much of New York with them. Subconsciously or otherwise, I dug into my historical position. I shall not be moved. I climbed aboard a similar municipal bandwagon in the mirror image year of ’69, embraced the Metropolitan ethos I encountered as a lad, and never thought to exit. In ’96, trends were whooshing in the other direction. I lived through that sort of reverse commute in the late ’70s, right around the same moment Time columnist Joel Stein was experiencing his baseball awakening as a kid in Jersey. Reggie. Billy. George. Toxic tea for those so inclined. In 2000, when the Subway Series loomed and the Yankee express had been running nonstop for five seasons, Stein explained the roots of his pinstriped allegiance: “My father, who grew up in the Bronx, took me to Yankees games. He is one of those tough Yankees fans who liked the Yankees aspirationally, because many lived the glamorous, drunken, bar-fighting, womanizing lives he wanted to lead, and then did after he got divorced.” Stein concluded that despite the Met motif better reflecting his own self-effacing tendencies, “I can’t get myself to switch allegiances…simply because the Yankees win.” Ya wanna be that way, fine — there’s a team for that. We knew that’s how their bandwagon rolled in 1996, even in the moments before it all became certifiably dynastic and intolerable. My sensibilities were offended that the Yankees of Joe Torre and Don Zimmer and Darryl Strawberry and David Cone (with Dwight Gooden having socked away a no-hitter) were getting points for being something akin to lovable underdogs. They’re not lovable. They’re never underdogs. Do your winning, but do it like the pricks you are. Hands off our brand equity. “Fuck you, I’m a Mets fan” was my attitude that September when “all of New York” was alleged to be excited about the Yankees. It carried me through October and toward those better days, too.

I felt something for this team amid the dregs of September that had been missing from the vast expanse of dismay that turned April through August into such a drag. A whiff of a hint of a clue that better days were ahead for this 91-loss jugger-NOT? Not exactly. The numerical pursuits of Todd Hundley (41 homers) and Lance Johnson (227 hits) certainly kept me leaning forward, but it was also what was going on across town. The Yankees were nearing their first divisional title in fifteen years and taking too much of New York with them. Subconsciously or otherwise, I dug into my historical position. I shall not be moved. I climbed aboard a similar municipal bandwagon in the mirror image year of ’69, embraced the Metropolitan ethos I encountered as a lad, and never thought to exit. In ’96, trends were whooshing in the other direction. I lived through that sort of reverse commute in the late ’70s, right around the same moment Time columnist Joel Stein was experiencing his baseball awakening as a kid in Jersey. Reggie. Billy. George. Toxic tea for those so inclined. In 2000, when the Subway Series loomed and the Yankee express had been running nonstop for five seasons, Stein explained the roots of his pinstriped allegiance: “My father, who grew up in the Bronx, took me to Yankees games. He is one of those tough Yankees fans who liked the Yankees aspirationally, because many lived the glamorous, drunken, bar-fighting, womanizing lives he wanted to lead, and then did after he got divorced.” Stein concluded that despite the Met motif better reflecting his own self-effacing tendencies, “I can’t get myself to switch allegiances…simply because the Yankees win.” Ya wanna be that way, fine — there’s a team for that. We knew that’s how their bandwagon rolled in 1996, even in the moments before it all became certifiably dynastic and intolerable. My sensibilities were offended that the Yankees of Joe Torre and Don Zimmer and Darryl Strawberry and David Cone (with Dwight Gooden having socked away a no-hitter) were getting points for being something akin to lovable underdogs. They’re not lovable. They’re never underdogs. Do your winning, but do it like the pricks you are. Hands off our brand equity. “Fuck you, I’m a Mets fan” was my attitude that September when “all of New York” was alleged to be excited about the Yankees. It carried me through October and toward those better days, too.

36. 1991

It’s July 13. The Mets win seven in a row right before the All-Star break and three directly after it, stomping on the Expos, the Phillies and the Padres in succession. We’re two-and-half out. Great, we’re making our move. It’s July 21. An up-and-down homestand ends with Doc Gooden beating the Dodgers by doubling a run home off Bobby Ojeda in the third and striking out Darryl Strawberry to end the fifth; serves them right for not being Mets anymore. We’re four out. Still plenty close, here we come. It’s August 8. After a messy trip out west, we take two out of three from the Pirates, the team we’re chasing, Gooden and Viola making the Bucs walk the plank on consecutive nights. We’re five-and-a-half out. Not ideal, but there are still two months to go and we’re gathering momentum. Three times my confidence has crested in the 1991 Mets. Thrice I have been convinced that my flawed team is ultimately capable of contention, meaning an eighth consecutive year of, at the very least, making a push in September is at hand. They lose 34 of their final 54 and no longer resemble the team I lived and died with from 1984 forward. They die on me in 1991. Rest in peace, Met era like no other.

35. 1989

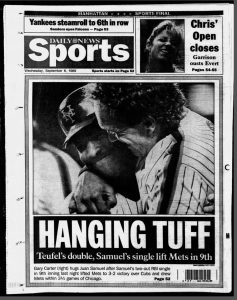

New Kids on the Block had a bunch of hits. One of them inspired the headline that graced the back page of the Daily News late that summer: HANGING TUFF. It wasn’t to describe the exploits of a lynch mob, but to assess how on September 5 the Mets, led by their veteran pinch-hitter, pulled out a walkoff win versus the Cubs at Shea, moving them to within 3½ games of first-place Chicago with 25 to play. With the score tied at two, Tim “Tuff” Teufel batted for starter Sid Fernandez with one out and doubled. Lou Thornton ran for him and moved up to third on Gregg Jefferies’s fly ball. Juan Samuel singled him in. After a torrent of tumult, turmoil and turbulence that transformed a flattering profile of the Mets as “the IBM of baseball” in Manhattan Inc. magazine into the prototype of a Freezing Cold Take and cast the season’s advertising slogan of “Excellence. Again and Again.” as the height of hubris, Amazin’ vibes reigned anew. The Mets had pissed away every chance to step up in the division, yet they were still standing, too good and too feisty to go quietly. Two weeks later, they were barely hanging on. A mini-scandal erupted with the revelation that their reaction to a 1-0 loss in Montreal was to file into the TV lounge off the visiting clubhouse and get engrossed in a football game —making “more noise than we make when we score a run,” per one “disgusted veteran” — just like any group of sports-minded guys on a Sunday afternoon. In their subsequent series at Wrigley, they brought more media grief upon themselves when Darryl Strawberry and Kevin McReynolds vacated the bench in the ninth inning of an apparently hopeless 10-3 game, perhaps to get an early start on changing into street clothes, maybe to check in on the Broncos-Bills tilt happening that Monday night. Except the Mets rallied at the ballpark where no lead is safe. Straw had to be summoned from the clubhouse to bat with two men out and three men on and the Mets suddenly trailing by four. Darryl struck out to end the game, with K-Mac grudgingly on deck. Davey Johnson fined the heart of his order. Elimination was inevitable. Teufel, the last hero of 1989, reflected as Met opportunity diminished, “No one should be surprised where we are. We’ve proven we’re a little better than a .500 club, and we’ve never done anything to become a .600 club.” Turned out they weren’t too good to go quietly. The club finished second, winning 87 times, but this edition never truly had the right stuff.

New Kids on the Block had a bunch of hits. One of them inspired the headline that graced the back page of the Daily News late that summer: HANGING TUFF. It wasn’t to describe the exploits of a lynch mob, but to assess how on September 5 the Mets, led by their veteran pinch-hitter, pulled out a walkoff win versus the Cubs at Shea, moving them to within 3½ games of first-place Chicago with 25 to play. With the score tied at two, Tim “Tuff” Teufel batted for starter Sid Fernandez with one out and doubled. Lou Thornton ran for him and moved up to third on Gregg Jefferies’s fly ball. Juan Samuel singled him in. After a torrent of tumult, turmoil and turbulence that transformed a flattering profile of the Mets as “the IBM of baseball” in Manhattan Inc. magazine into the prototype of a Freezing Cold Take and cast the season’s advertising slogan of “Excellence. Again and Again.” as the height of hubris, Amazin’ vibes reigned anew. The Mets had pissed away every chance to step up in the division, yet they were still standing, too good and too feisty to go quietly. Two weeks later, they were barely hanging on. A mini-scandal erupted with the revelation that their reaction to a 1-0 loss in Montreal was to file into the TV lounge off the visiting clubhouse and get engrossed in a football game —making “more noise than we make when we score a run,” per one “disgusted veteran” — just like any group of sports-minded guys on a Sunday afternoon. In their subsequent series at Wrigley, they brought more media grief upon themselves when Darryl Strawberry and Kevin McReynolds vacated the bench in the ninth inning of an apparently hopeless 10-3 game, perhaps to get an early start on changing into street clothes, maybe to check in on the Broncos-Bills tilt happening that Monday night. Except the Mets rallied at the ballpark where no lead is safe. Straw had to be summoned from the clubhouse to bat with two men out and three men on and the Mets suddenly trailing by four. Darryl struck out to end the game, with K-Mac grudgingly on deck. Davey Johnson fined the heart of his order. Elimination was inevitable. Teufel, the last hero of 1989, reflected as Met opportunity diminished, “No one should be surprised where we are. We’ve proven we’re a little better than a .500 club, and we’ve never done anything to become a .600 club.” Turned out they weren’t too good to go quietly. The club finished second, winning 87 times, but this edition never truly had the right stuff.

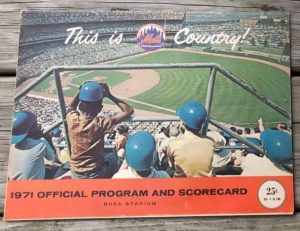

34. 1971

When Rosalynn Carter died in 2023, it was noted that she and Jimmy lived in the same “modest” house they moved into in 1961. Of course there were extended stretches when they bedded elsewhere, like when Jimmy was governor and president, yet they always returned to Plains, Ga. The 1971 season may be my version of their humble abode at 209 Woodland Drive. Homey. Comfortable. Sufficient as long as we had our trophy from 1969 sitting over the fireplace to remind us we’d been somewhere. It was a New York Met state of mind I got used to. Tom Seaver was magnificent. Everybody else was more or less OK. The team was good enough to not be bad, lacking too much to be great. It wasn’t a whole lot different from 1970, except Pittsburgh put more space between themselves and the rest of the East, so no pennant race transpired, at least not one involving us. There was a little more Ken Singleton, who the announcers seemed excited about, and they loved to tell us Danny Frisella threw a forkball. Don Hahn was here instead of Ron Swoboda. Mostly the same agreeable roster. Exactly the same respectable record of 83-79. I was eight and semi-content to tie for third if this was how it was gonna work every year…though even homebody Jimmy Carter aspired to hold office in Atlanta and Washington, and then traveled the world ambitious to make a difference for as long as his health would allow him. So, yeah, you need to have goals. And, no, you can’t live in 1971 forever.

Ah the teens. I remember them well. Good memories. I mean — mediocre memories (shrug).

I’ve never seen (and, before this post, never heard of) Bright Young Things, but did anyone else notice that the cast appears to be studded with stars/well-known names…none of whom appear on the poster?

Chin Lung Hu. The only player with two body parts in his name.

Bill Hands, if his mom screwed a platypus.

Interesting that you rated 2011, 2012, and 2013 as a trio. To me those are the most interchangeable three consecutive seasons in Mets History.