Just in time for Pitchers & Catchers, we have broken into the Top 20 portion of MY FAVORITE SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT. The focus of this entry is neither a pitcher nor a catcher, but he does happen to be somebody who will be reporting to Port St. Lucie in the company of this year’s batterymates in the days ahead. In a happy accident of my not having picked up the pace on this project, this look back through one fan’s lifetime of rooting for teams he didn’t love that much; loved somewhat; loved a whole lot; and, ultimately, loved more than any other is actually kind of timely.

You’ll recognize the modern-day Met in question in about a minute if you haven’t already. Here’s hoping that player’s current contractual situation is resolved to our liking before we are tempted to apply regret to our long-term reading of how we arrived at his professional crossroads. We know we have him at the outset of 2024. We yearn to hear we’ll have him in 2025 and beyond. But no matter what the near future holds, we will always know what we had when we first wrapped our arms around who he was and what he could do for us. I’m certain I will always be glad the wrapping began when it did.

20. 2019

In the runup to the 2019 season, new camera-ready general manager Brodie Van Wagenen communicated a lot of things to the media, including, around mid-January, this assessment of the offseason he’d conducted to date:

“We are a good team. We are a complete team, we are a balanced team. We’ve got veterans, we’ve got youth, we’ve got a hunger and desire to win and I look forward to showing people we’re a team to be reckoned with. Let’s not be shy about wanting to be the best, and I fully expect us to be competitive and be a winning team. Our goal is to win a championship and it starts with the division, so come get us.”

The last three words, uttered on the occasion of the Mets signing the cherry on top of Van Wagenen’s winter, former Oakland middle infielder Jed Lowrie, had Freezing Cold Take penciled all over it once the Mets dipped below .500 in early May. “Come get us” might as well have been the team’s and the GM’s epitaph by the All-Star break, a juncture that found the Mets ten games under and holding the second-worst record in the entire league. With any luck, the Mets figured to improve from what they’d been in 2018 (77-85), but were neither the consensus pick nor a “smart money” selection to upend the National League East. “We’re coming for you” would have been a more appropriate tone to strike a year after languishing in fourth place. Hubris was a hairdo that didn’t accent these Mets’ better features.

If you shared your thoughts about the Mets with any kind of audience in 2019 and you wanted to score a chagrined grin at the expense of a very handsome man, you reminded everybody reading or listening of the dare Van Wagenen left on the doorsteps of the Braves and the Nationals and how the competition was in the process of responding (the Braves were en route to winning the East and the Nationals would cash in the Wild Card for their first world championship). BVW, as he was destined to be shorthanded in these social media times, knew when foot fit mouth. Ahead of the second half, he admitted to reporters, “They came and got us.”

But Brodie Van Wagenen, as mentioned, said a lot of things ahead of the first Met campaign played on his watch, including three less celebrated sentences just prior to the opening of the 2019 season. Within his tumultuous tenure’s mixed bag of quotations and transactions, perhaps a little more attention needed to be paid to this sentiment:

“I’m not of the mindset that we should be sacrificing the best product for the fans or the best product for the other 24 guys in the clubhouse to save service time or potential future money six years down the road. If Pete Alonso or anybody on our roster is good enough to have six consecutive years without having a hiccup, or without ever having to go to the minor leagues, that’s a good, high-class problem for the player. It’s a high-class problem for the organization.”

Sometimes class tells. Sometimes a GM continually and not unfairly strafed for setting an unrealistic bar knew what he was doing. Sometimes a mixed bag implies there are some tasty morsels included among the dregs.

Rookie first baseman and potentially prodigious slugger Pete Alonso made the Opening Day roster of the 2019 Mets. it was no sure thing. True, their 2018 predecessors were no great shakes; there was no incumbent with a hammerlock on Pete’s position; and the kid had dominated Triple-A pitching. Only in Major League Baseball would that confluence of circumstances not mean a job definitely awaited a young comer. But Pete played baseball. Baseball liked to tell kids who were ready to go in March that they should stick around the minors for a few weeks and cool their heels, lest they accumulate the service time that would make them free agents a year sooner six years from now.

Yet Pete made the Mets out of Spring Training 2019, circumstances for the offseason that would precede 2025 be damned. Brodie will always rate a gold star for not making Pete or Mets fans wait one minute more. Pete took advantage of his organic start to his first season and blew away whatever hype we’d heard. His first game was Opening Day. His first home run came in the Mets’ fourth game. Twelve games into his major league career, he had six home runs. He ended April with nine. By May, the month I had the privilege of finally witnessing in person one of his Citi Field bombs (No. 16, confirmed fair by replay review), I took it upon myself to start tracking his power progress versus the co-holders of the Met single-season home run recordholders, Todd Hundley (1996) and Carlos Beltran (2006), as well as the fella who, until he was halted by injury, was going to put the record out of reach for a generation, the legendary Dave Kingman in 1976.

Yet Pete made the Mets out of Spring Training 2019, circumstances for the offseason that would precede 2025 be damned. Brodie will always rate a gold star for not making Pete or Mets fans wait one minute more. Pete took advantage of his organic start to his first season and blew away whatever hype we’d heard. His first game was Opening Day. His first home run came in the Mets’ fourth game. Twelve games into his major league career, he had six home runs. He ended April with nine. By May, the month I had the privilege of finally witnessing in person one of his Citi Field bombs (No. 16, confirmed fair by replay review), I took it upon myself to start tracking his power progress versus the co-holders of the Met single-season home run recordholders, Todd Hundley (1996) and Carlos Beltran (2006), as well as the fella who, until he was halted by injury, was going to put the record out of reach for a generation, the legendary Dave Kingman in 1976.

I couldn’t go deep on the subject of Met moonshots without thinking about Sky King. Unless a few stray Bicentennial fireworks knocked a couple of his longballs off course, a Mets fan in the summer of ’76 had every reason to believe Kingman was going to place Hack Wilson’s National League standard of 56 home runs in danger. Dave swatted his 32nd home run in the Mets’ 92nd game, a pace four games better than Pete’s 43 years later. Alas, in their 93rd, he messed up a thumb attempting to play defense and would miss too much time to take his hack at Hack. Dave wound down 1976 with 37 home runs, which did establish a new Met record (breaking his own from 1975), but not one you required a telescope to detect. In a way, Pete’s only legitimate competition was eliminated more than three decades before the rookie took his first swing.

Hundley and Beltran, who finished their big years with 41 home runs apiece, proved modest hurdles for Alonso. Within Pete’s first 50 games, the Polar Bear — an apt and adorable nickname contemporary accounts suggest was crowdsourced by some combination of Todd Frazier, Noah Syndergaard and coach Gary DiSarcina — had gone over fences 17 times. By comparison, Todd required 64 games to hit that many home runs and Carlos needed 60. By the time Pete experienced a brush with a home run drought (no homers between Met Game 103 and Met Game 113), Pete’s cushion separating him from his predecessors was a veritable sofa bolster. The rookie who’d hit the most Met home runs previously, Darryl Strawberry in 1983, likewise couldn’t retroactively keep up. Strawberry, whose 39 homers in 1987 would surpass Kingman’s Met best from eleven years earlier, was promoted to the bigs on May 6 of his first year and put those nearly five months of NL action to very good use, clouting 26 homers and earning Rookie of the Year honors. His 1983 total seemed like such a formidable freshman number for so long, but Pete left Darryl’s initial quantity in the dust before the first half of 2019 was over. In only three months, that line of the Met record book was rewritten.

Hundley and Beltran, who finished their big years with 41 home runs apiece, proved modest hurdles for Alonso. Within Pete’s first 50 games, the Polar Bear — an apt and adorable nickname contemporary accounts suggest was crowdsourced by some combination of Todd Frazier, Noah Syndergaard and coach Gary DiSarcina — had gone over fences 17 times. By comparison, Todd required 64 games to hit that many home runs and Carlos needed 60. By the time Pete experienced a brush with a home run drought (no homers between Met Game 103 and Met Game 113), Pete’s cushion separating him from his predecessors was a veritable sofa bolster. The rookie who’d hit the most Met home runs previously, Darryl Strawberry in 1983, likewise couldn’t retroactively keep up. Strawberry, whose 39 homers in 1987 would surpass Kingman’s Met best from eleven years earlier, was promoted to the bigs on May 6 of his first year and put those nearly five months of NL action to very good use, clouting 26 homers and earning Rookie of the Year honors. His 1983 total seemed like such a formidable freshman number for so long, but Pete left Darryl’s initial quantity in the dust before the first half of 2019 was over. In only three months, that line of the Met record book was rewritten.

Pete was running roughshod over modern-day pitching, and franchise history couldn’t keep up with him, either. As 2019 went on, it was clear Pete Alonso was doing things in terms of home runs no Met had done before. It was just as clear to me that I was never as thrilled by any individual Met’s pursuit of any type of benchmark, record or title as I was by Pete’s. The thrill transcended mere statistics because, despite the skies over Shea and Citi having been effectively pierced by the likes of Kingman, Strawberry, Hundley and Beltran, this simply wasn’t an outfit defined by balls it put over walls.

When it came to four-baggers, we’d always ordered our most dramatic and memorable à la carte.

• Willie Mays coming home to the city that never didn’t consider him its own, May 14, 1972.

• Steve Henderson making Magic real, June 14, 1980.

• Gary Carter trying on orange and blue and demonstrating how well it fit, April 9, 1985.

• Mike Piazza when nobody knew what to expect other than Mike Piazza doing something dramatic and memorable, September 21, 2001.

• Wilmer Flores absolutely not getting traded, July 31, 2015.

Donn Clendenon in the World Series. Al Weis in the World Series. Lenny Dykstra and Benny Agbayani to end playoff games. Todd Pratt to end a playoff round. Lee Mazzilli late one All-Star night. Throw in Tommie Agee and Curtis Granderson from the leadoff spot; Yoenis Cespedes and his enormous spurt; Howard Johnson going on rolls; Lucas Duda, too. Circle back to Piazza, the Ginger Rogers of power hitters. He hit them far, he hit them often, and he hit them while half the time doing the baseball equivalent of backwards and in high heels. Mike crouched, called games and looked out at the field as only the catcher does.

Yet even Mike Piazza with his flair for the dramatic and memorable didn’t make home runs the main course of the Met menu. It was like we were on a restricted diet. When we were good, we were about pitching, glovework and fairy dust. What should be our most famous not to mention dramatic and memorable postseason home run went into the books as a grand slam single. Pratt tackled Robin Ventura before Robin Ventura could touch second let alone home. No thanks, Tank seemed to tell his teammate amid the delirium of October 17, 1999, we can’t eat another bite. It’s still dramatic and memorable, but it’s missing more than 180 feet worth of calories.

Another third baseman, David Wright, should have been, per the terms of his contract and the arc of the healthy segment of his career, extending his all-time franchise home run record in 2019. Except he stepped aside for good in 2018, having been sidelined for all but a couple of games that year and completely out of action the year before that and most of the two years before that. Wright, a steady rather than spectacular slugger, completed his Met clouting at 242 home runs, ten shy of Strawberry’s 252. Strawberry’s 252 were like Hundley’s and Beltran’s 41. Really, really good when you stopped and thought about it, but once you realized what home run figures other franchises had inked into their annals, not exactly super.

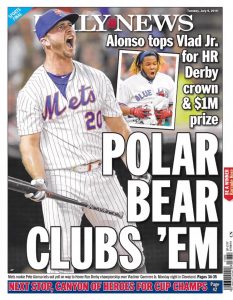

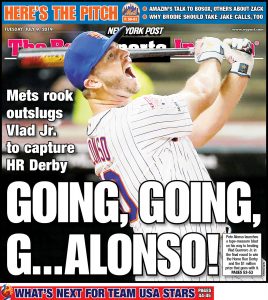

Then along comes the Polar Bear, almost unstoppable in the home run category practically from Day One, definitely in Year One, giving us permission to gorge. Somehow something that Pete made mundane qualified as an event. Another Apple-raiser for Alonso! In another era, crowds would have gathered in Times Square to learn of his exploits from the news racing around the zipper, the town, the nation, the world to keep up with the newly crowned Home Run Derby champ. His 30th! His 40th! His 41st to tie the Met record! His 42nd to break it! His blitz through the forties and, ohmigod, his 50th! A Met hit 50 home runs! Then a 51st! A 52nd, tying the all-time rookie record with two games left! And, in the season’s penultimate game, Pete Alonso of the New York Mets hit his 53rd home run, more than any rookie ever, more than anybody in Major League Baseball in 2019. He was already fewer than 200 from Strawberry’s Met career mark and he’d played precisely one season.

Then along comes the Polar Bear, almost unstoppable in the home run category practically from Day One, definitely in Year One, giving us permission to gorge. Somehow something that Pete made mundane qualified as an event. Another Apple-raiser for Alonso! In another era, crowds would have gathered in Times Square to learn of his exploits from the news racing around the zipper, the town, the nation, the world to keep up with the newly crowned Home Run Derby champ. His 30th! His 40th! His 41st to tie the Met record! His 42nd to break it! His blitz through the forties and, ohmigod, his 50th! A Met hit 50 home runs! Then a 51st! A 52nd, tying the all-time rookie record with two games left! And, in the season’s penultimate game, Pete Alonso of the New York Mets hit his 53rd home run, more than any rookie ever, more than anybody in Major League Baseball in 2019. He was already fewer than 200 from Strawberry’s Met career mark and he’d played precisely one season.

WOW!!!!

Yet one player does not make a season. I base this assertion on having lived through Pete’s very exciting power show when it served as counterpoint to the way the Mets were going as a whole, and I gotta say, what the Mets besides Alonso (along with that Jacob deGrom fellow on his way to another Cy Young) were giving us wasn’t much of a 2019.

Until it was. That took everybody’s contribution. Suddenly, in late July, right around the moment Pete matched Frank Thomas’s original single-season Met home run record of 34, the hat was being passed incredibly effectively. From Jeff McNeil to Michael Conforto to J.D. Davis to Amed Rosario to Wilson Ramos until it reached Dom Smith in the eleventh inning of the season’s final game. Every Met was kicking in a little, then a lot. The team Van Wagenen constructed was living up to the GM’s chest-puffing at last.

Pete hitting a ton of home runs while the Mets stumbled to a 40-51 start: plenty fun when he batted, not much fun otherwise.

Pete hitting a ton of home runs while the Mets racked up a 46-25 finish: baseball like it oughta be.

The 86-76 Mets didn’t assume the guise of a contender until it was a tad too late to dent the playoff race in earnest. Ah, but we didn’t fully know that until we claimed hindsight on irrevocable waivers. We sensed it repeatedly in late August and early September and mid-September, the way you do when you know deep down you’re bound to fall a little short, yet every time we were ready to throw in the towel, the linen would not leave our hand. Our Mets had gotten good enough all at once to let us believe, and that’s always dangerous when we’re determined to be realists. When it was finally too late to any longer deny the inevitable, after a one-run loss in Cincinnati during the season’s second-to-last weekend stuck the club 4½ out of the final playoff spot with eight to play, Todd Frazier tried like hell to work the long mathematical odds in the Mets’ favor. “I felt like we had to go 9-1” down the stretch, the Toddfather reasoned. “Here’s our one.” I knew desperation was talking and didn’t invest much hope in Frazier’s calculation. They were indeed ousted from the race a few days hence.

Still, Todd from Toms River wasn’t necessarily talking crazy. He was part of a team that between July 25 and August 10 went 15-1 and completely changed the tenor of their season. From a unit that was mainly about Pete Alonso hitting home runs, they evolved into a unit that was all about winning games, contending for a Wild Card and having a blast while trying to pick up ground. The veterans, the youth, the hunger and desire to win that Brodie Van Wagenen promised in January were all in evidence. It was during the 15-1 stretch that they started pulling off the jersey of the given evening’s hero to celebrate walkoff wins; that players not named Pete Alonso began getting our attention for Amazin’ feats; that LFGM became an accepted spelling for Let’s Go Mets; and that anything began to seem possible. It didn’t propel the 2019 Mets to come get a playoff spot when it seemed like they had a real chance, but it was enough to transform a season that had been a veritable one-man show into the kind of team effort that keeps a fan tuning in out of anticipation rather than habit.

Still, Todd from Toms River wasn’t necessarily talking crazy. He was part of a team that between July 25 and August 10 went 15-1 and completely changed the tenor of their season. From a unit that was mainly about Pete Alonso hitting home runs, they evolved into a unit that was all about winning games, contending for a Wild Card and having a blast while trying to pick up ground. The veterans, the youth, the hunger and desire to win that Brodie Van Wagenen promised in January were all in evidence. It was during the 15-1 stretch that they started pulling off the jersey of the given evening’s hero to celebrate walkoff wins; that players not named Pete Alonso began getting our attention for Amazin’ feats; that LFGM became an accepted spelling for Let’s Go Mets; and that anything began to seem possible. It didn’t propel the 2019 Mets to come get a playoff spot when it seemed like they had a real chance, but it was enough to transform a season that had been a veritable one-man show into the kind of team effort that keeps a fan tuning in out of anticipation rather than habit.

Moral: tracking a ballclub’s collective success beats tracking that of one individual, no matter how powerful the Polar Bear in the spotlight.

PREVIOUS ‘MY FAVORITE SEASONS’ INSTALLMENTS

Nos. 55-44: Lousy Seasons, Redeeming Features

Nos. 43-34: Lookin’ for the Lights (That Silver Lining)

Nos. 33-23: In the Middling Years

Nos. 22-21: Affection in Anonymity

Speaking as a fan, I would have had Conforto back. Not sure what happened there.

I am going to miss Pete when he leaves, and I hope he continues his success elsewhere. He is the best hitter the Mets have ever had, and that includes our best DH ever, Mike Piazza.

I loved Dave Kingman. He was a really nice guy when he made an appearance at a batting cage near Rockaway Beach in 1985 and took a picture with me (as well as with others).

The great Jerry Girard of WPIX said of Kingman on one of his sportscasts:

“The Mets were rained out today, and the only time I ever saw Kingman happier was when they were rained out of a doubleheader.”

Hoping Pete gives unequivocal evidence we should re-sign him this year. He’ll hit a bunch of balls out but a .217 BA to go with it? That’s gonna give me some conflicting feelings when it comes time to pay him big money. Batting .260 or so changes that.

As I recall, he went into that tailspin after he came back too soon from getting plunked by Atlanta.