“I was very fortunate to win three-hundred and eleven games, and not many people in the wonderful history of baseball were able to go past three-hundred,” said the man in the suit at the podium. “And you wonder why it happened? All you have to do is look at the individuals that were sixty feet, six inches away from me through a twenty-year career. How very fortunate I was to have three people that were my basic catchers through a twenty-year career, starting with Jerry Grote, ten-and-a-half years with the New York Mets.”

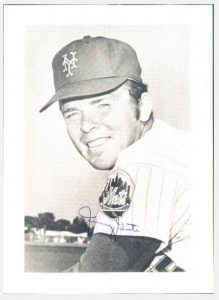

The man in the suit taking the time at the podium on a day that served as the capstone of his magnificent career was Tom Seaver. The podium’s location was Cooperstown, New York. And sixty feet, six inches away from the location he stood when he was making his case to someday be accepting induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame was indeed his catcher, Jerry Grote [1].

Nothing basic about Grote as a catcher, though. Tom knew that. We all knew that.

The mere fact that Jerry Grote was being mentioned as one-third of a triumvirate that included Carlton Fisk, who would be accepting the same honor as Seaver eight years down the line, and Johnny Bench, already enshrined as a member of the same exclusive club three years by then, spoke volumes. Close your eyes, and you can see Fisk and Bench hitting massive home runs. Keep your eyes closed and picture Grote. He’s catching.

He’s catching Tom Seaver. He’s catching Jerry Koosman. He’s catching Nolan Ryan. He’s catching Gary Gentry. He’s catching Don Cardwell. He’s catching Jon Matlack. He’s catching veterans. He’s catching rookies. He’s catching every Mets starting pitcher you can picture from 1966 to 1977, beginning with Jack Fisher (after Grote was practically stolen from Houston) and ending with Nino Espinosa (before Grote was mercifully traded to L.A.).

[2]He’s the catcher to a generation and then some. We see him behind the plate. We see him up and at ’em, perhaps more than any Met ever got up and at ’em. Up and out of his crouch and after a foul fly. Up and out of his crouch and gunning a throw to second. Up and out of his crouch to get his pitcher on the right page. Up and on to great things for his team. Up and off to a splendid career of his own, one that earned him inclusion in the Mets Hall of Fame, where he is, per Seaver’s equation, one of three. Gary Carter is in there. He came later. Mike Piazza is in there. He came later. As with Bench and Fisk, they have plaques in Cooperstown. As with Bench and Fisk, they went deep dramatically and regularly.

[2]He’s the catcher to a generation and then some. We see him behind the plate. We see him up and at ’em, perhaps more than any Met ever got up and at ’em. Up and out of his crouch and after a foul fly. Up and out of his crouch and gunning a throw to second. Up and out of his crouch to get his pitcher on the right page. Up and on to great things for his team. Up and off to a splendid career of his own, one that earned him inclusion in the Mets Hall of Fame, where he is, per Seaver’s equation, one of three. Gary Carter is in there. He came later. Mike Piazza is in there. He came later. As with Bench and Fisk, they have plaques in Cooperstown. As with Bench and Fisk, they went deep dramatically and regularly.

Grote could hit some, but all you really see is the catcher. Grote could talk some, all his pitchers would confirm with a knowing chuckle, but they listened, because he was the catcher. Basic? Primary. He had some capable backups, but with everything on the line, Gil Hodges (who came up as a catcher) and Yogi Berra (in the Hall himself as a catcher) never looked beyond No. 15 from San Antonio. The Mets played twenty postseason games with Grote on their roster. Every inning and every pitch was handled behind the plate by one man.

I have a new favorite Jerry Grote stat, one I was moved to confirm on Sunday night, a few hours after the Mets had beaten the Reds [3] in Cincinnati by a pitching-friendly score of 3-1, minutes after learning Jerry had passed away [4] at 81. The legend of the 1973 Mets centers on their pedestrian regular-season record, inevitably processed as the best of a so-so assortment of contenders, implying they were some kind of fluke. Yes, they went 82-79, which in pre-Wild Card times usually meant you weren’t going to the playoffs. And, yes, the Mets had to pull themselves out of the last-place muck to get where they needed to go practically in a blink. One of the elements of the pennant drive that has survived anecdotally, at least among the Met faithful, is the Mets got going once they had their regulars healthy again.

How does that translate from anecdotal to statistical? Well, on May 11, the night Grote was hit by a Ramon Hernandez pitch and suffered a fracture to a bone his right arm, the Mets were above .500, sitting in second place, a couple of games from the division lead. The next time Jerry was in the starting lineup, on July 13, the Mets were languishing in last, way under .500, far removed from first place. Yet first place, with Jerry Grote taking every start down the stretch, is where the Mets ended up.

To borrow from Tom Seaver, “and you wonder why it happened?”

When Jerry Grote was in the starting lineup for the 1973 New York Mets, the record of the 1973 New York Mets was 47-29, the kind of pace that captures pennants. Jerry Grote made his pitchers better and made his team better. He also made his competitors’ eyes pop. Bench the slugger, who won ten consecutive Gold Gloves for the Reds from 1968 to 1977, famously said that had Grote been in Cincy, he himself would have been the third baseman. Lou Brock, the sultan of stolen bases, identified Jerry as his most effective nemesis. “He’s the toughest catcher in the league to try and steal against,” Lou said in 1968, the year NL players voted Grote to start the All-Star Game (Bench was his backup).

It was rewarding to know Grote won the respect of so many peers and rivals, but it was even better when you were a kid growing up as a Met fan to see the man in action. The way they used to televise baseball games, from behind home plate, No. 15 usually had his back to us. He’d be the first Met we saw. Then one of his pitchers would throw him a strike. We’d take in the entire picture and we’d figure out that the Mets stood an excellent chance of winning as long as our catcher was where we counted on him to be. Jerry Grote’s presence told us all that.