Sometimes you stumble into something that catapults you toward something else. Shortly before the Mets, amid Sean Manaea’s off afternoon and a surfeit of Bobby Witt, stumbled Saturday into their 11-7 loss to the Royals, I stumbled into a nugget of information totally new to me. Sixty years ago, on April 13, 1964, the Mets held a season’s eve workout, itself nothing unusual. The club was about to travel to Philadelphia to begin its third year of existence, so they figured they’d get the last of their Spring Training in at home.

Except home wasn’t ready. Shea Stadium would open on April 17, and those who were finishing it up needed every last minute to put every detail in place. Hence, the Mets held their workout at Hofstra University in Hempstead. Hofstra! The same Hofstra a few Meadowbrook Parkway exits from where I grew up, the same Hofstra literally down the block from the home of the Nets (1972-1977), the same Hofstra that served as summer camp and base of operations for the Jets (1968-2008). But the Mets? As far as I knew until this weekend, Hofstra held only two connections to the Mets.

1) My friend Dana Brand, who defined what it meant to be a Mets Fan, taught American Literature there.

2) Dana organized an academic conference devoted to the Mets that coincided with their 50th anniversary in 2012, one year after Dana died without warning. That wonderful event had Dana’s imprint all over it.

Now, I had a third reason to connect Hofstra and the Mets: the 1964 workout that, according to Newsday, had the same effect on the neighborhood’s baseball fans that the Beatles showing up in Manhattan had on the musically inclined two months earlier.

“The scene at Hofstra — where a crowd of about 1,500, mostly small boys, turned up — was one of joyful pandemonium,” Joe Donnelly reported. “With no fences along the foul lines, it was every Met for himself against three-dozen or so boys who came equipped with gloves and engaged their idols in glove-to-glove war for every loose ball.”

“The scene at Hofstra — where a crowd of about 1,500, mostly small boys, turned up — was one of joyful pandemonium,” Joe Donnelly reported. “With no fences along the foul lines, it was every Met for himself against three-dozen or so boys who came equipped with gloves and engaged their idols in glove-to-glove war for every loose ball.”

It’s not that the Mets didn’t want to be generous. It’s that the Mets brought all of sixty baseballs to practice with and, well, they were gonna run out before every player could take his swings. The Mets’ paucity was the fans’ potential bounty. Aching for a foul ball from the stands was one thing, but this was the horsehide equivalent of scheming for a few locks of hair off the heads of the Lads from Liverpool and magically being granted a barber’s license.

“They’d knock you down for a ball,” 19-year-old Ed Kranepool told Donnelly. “They’re friendly enough — but they want souvenirs.” The Mets responded, per Donnelly, by playing some of their most diligent defense to date. “As the supply of baseballs dwindled,” he wrote, “certain Mets, who wanted another batting practice turn, gave their greatest fielding exhibitions as they hustled to retain baseballs.”

Desired keepsakes included the players’ caps or maybe the players themselves, for once BP could be extended no further, the “friendly enough” kids chased the Mets, presumably out of adoration, to their temporary clubhouse beyond left field so they could shower, dress and prepare for the season ahead in one piece. Coach Wes Westrum, who caught for the Giants when the Giants belonged to New York, compared the scene that ensued at day’s end to the jubilant hordes at the Polo Grounds who poured onto the field when Bobby Thomson launched his Shot Heard ’Round the World in 1951, “only there were many more cops to hold the fans back that day.”

Duke Snider, who was about to have his wish to move to a contender granted with the sale of his contract to San Francisco, summed it up:

“This was a typical Met afternoon.”

Let us hope a couple of difficult but not impossible fly balls that couldn’t be caught — one clanking off the glove of Starling Marte for three bases, another barely out of the grasp of Brandon Nimmo en route to it becoming a home run for Salvador Perez — doesn’t represent a typical Met afternoon nowadays. If Saturday’s matinee was, save for Pete Alonso going deep twice, atypical, Sunday’s finale versus Kansas City looms as extraordinary for what will precede it.

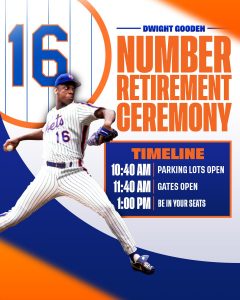

On Sunday, the Mets are retiring 16 for Dwight Gooden. The last time the Mets retired a uniform number on a Sunday afternoon, it was 1988, the number was 41, and its bearer was Tom Seaver. The vagaries of scheduling presumably accounts for Doc’s honor landing on the same day of the week as Tom’s, but it sure seems appropriate. In the annals of Met acedom, there’s Tom, then Doc.

On Sunday, the Mets are retiring 16 for Dwight Gooden. The last time the Mets retired a uniform number on a Sunday afternoon, it was 1988, the number was 41, and its bearer was Tom Seaver. The vagaries of scheduling presumably accounts for Doc’s honor landing on the same day of the week as Tom’s, but it sure seems appropriate. In the annals of Met acedom, there’s Tom, then Doc.

The Mets retired 41 the season after Seaver brushed the last of the dirt from his right knee and hung up his glove for good. They waited nearly a quarter-century after Gooden’s final professional pitch to hoist 16 to the rafters. The organization used to be slow about these things if your name wasn’t Tom Seaver. The organization was also slow to recover from the time it stumbled mightily and traded Tom Seaver. That happened in 1977. The Mets weren’t remotely the same again until Dwight Gooden came along in 1984, throwing fast and going places faster. “There’s Tom, then Doc” worked as an irrefutable Metsian construct by 1985.

But let’s not be too harsh on the subject of stumbling. Stumbling into that Mets-at-Hofstra interlude indeed catapulted me into something else. Once I had Hofstra and Dana Brand on the brain, I picked up Dana’s first book to read how he framed the arrival of Dwight Gooden onto the Mets’ heretofore arid landscape and the explosion of Dwight Gooden into our everlasting consciousness. Professor Brand’s interpretations were and are consistently delightful and reliably insightful.

Dana quoted an array of statistics from 1984 and 1985 that translate as enormous now as they were to experience then, before concluding that, while baseball isn’t only “about numbers,” sometimes “the only language we have” for expressing “the sublime, the beautiful terror of magnitude” of output like Doc’s “is numbers”.

One of the greatest pleasures I have had as a Mets fan was seeing Gooden when he was 19 and 20. I remember the games behind these numbers. I remember him striking out the side in his first All-Star game appearance. I remember him striking out 16 batters in two consecutive games. I remember how perfectly unhittable he was. I remember how excited I was. I remember what it felt like as these unprecedented numbers assumed their permanent form. I savored them, I thought of them over and over. I couldn’t believe that I was alive to see this. I couldn’t believe that this was being done by a Met.

Me from 1985 couldn’t believe it, either. Me from 1986 through 1994 never believed the same Doc wasn’t still pitching for the Mets. Of course he was. A little less spectacular as the years went by, a little worn down by time and travails, but still Doc. Then one day he wasn’t a Met, and 16, so indelibly associated with one player and one phenomenon, eventually landed on the jerseys of those who were Mets. If Dwight Gooden wasn’t going to wear it, somebody had to, it was supposed. A few times it was issued to players (Derek Bell, David Cone during his brief comeback, Rick Ankiel), who wished to pay homage to the No. 16 who used to strike out 16 at a clip. A few other times, a player would show up who could claim his own history with the digits (Hideo Nomo, Doug Minetkiewicz, Paul Lo Duca) and have his personal preferences deferred to. But after a while, it became just another number that got issued to commonfolk just passing through (Rob Johnson, Danny Muno, Kevin Kaczmarski). Pinch-runner deluxe Travis Jankowski was the most recent Met to wear 16, in 2022.

Last August, the Mets announced their institutional amnesia had been cured. Me from 1985 couldn’t believe how common 16 had become. Me in 2023 was a mixture of relieved and elated when it was announced 16 would no longer be thrown into the uniform lottery every February. It deserved better. He deserved better.

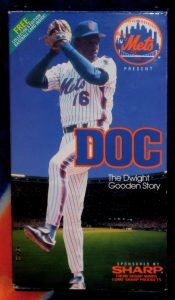

If we frame what Dwight Gooden did as a Met in Hollywood terms, Doc was the major studio release that proved a summertime blockbuster, completely exceeding the most optimistic of industry forecasts. They then made a sequel, and Doc II did even better, shattering box office records, drawing critical raves and winning every major award. Doc loomed as a lucrative franchise.

So they kept making sequels. Doc III, which opened to massive expectations in 1986, did all right by most standards, but fell short of what diehards were anticipating. Doc IV had problems in production, let’s say, and didn’t hit screens until June 1987. It did OK, but nobody embraced the turn the main character had taken. The controversial climactic scene of 1988’s Doc V detracted from what had been a good, solid popcorn flick; you wish they could fiddle with CGI and release a Scioscialess cut. A loyal following ensured there’d continue to be an audience for Doc content, though by the mid-1990s, everything this studio was putting out carried a straight-to-video stigma.

So they kept making sequels. Doc III, which opened to massive expectations in 1986, did all right by most standards, but fell short of what diehards were anticipating. Doc IV had problems in production, let’s say, and didn’t hit screens until June 1987. It did OK, but nobody embraced the turn the main character had taken. The controversial climactic scene of 1988’s Doc V detracted from what had been a good, solid popcorn flick; you wish they could fiddle with CGI and release a Scioscialess cut. A loyal following ensured there’d continue to be an audience for Doc content, though by the mid-1990s, everything this studio was putting out carried a straight-to-video stigma.

Nobody much worries that the latter versions of Jaws didn’t live up to the original. I understand if you get on a tram at Universal Studios, you’ll still be exposed to a mechanical shark. Whatever isn’t beloved about The Godfather Part III doesn’t keep anybody from quoting the first two films with reverence. Rocky V…you get the picture. Sometimes there may be every business reason to keep churning out sequels, even if they don’t hold up as well as what preceded and inspired them.

Thing is, Dwight Gooden wasn’t only 1984 and 1985. The nine-season coda to the two-season tour de force that made him a legend was still the stuff of upper-level mortals. Doc won 157 games for the Mets, more than anybody else not named Tom Seaver. He didn’t win them all at once. It only feels like he did because what he did out of the box overwhelms whatever else was packed into his Met career. He pitched spectacularly for a couple of years. He pitched well for long time.

The Doc who will be at the ceremonial center of Sunday started 303 regular-season games for the Mets, which means some other pitcher started against him 303 times. Pitchers talk about facing opposing lineups, but we as fans love to dive into pitchers versus pitchers — mound opponents, mound duels. When we think about pitchers going up against each other, the fellows with the bats seem almost incidental. Given the magnitude 16 is about to take on, I rifled through Gooden’s game logs on Baseball Reference in search of one statistic in particular:

How often did Doc go up against a starting pitcher who went on to have his number retired?

As we’ve seen by the way the Mets have gone about it, number retirement is more art than science, and more impressionism than any other art form. There are no leaguewide regulations governing who may be deemed worthy. Every franchise has its own reasons for bestowing or not bestowing its own ultimate in-universe honor upon a given player, until the rules are bent or rewritten or cast aside, because some things you just know in your gut are the right things to do.

Doc faced off against a lot of really good pitchers in his Met tenure, pitchers I could imagine having their numbers retired under the right circumstances. Some of Gooden’s most distinguished mound opponents earned praise and accolades and took home serious hardware at their peak, but it didn’t usher them onto whatever wall or rafter a team for whom they excelled uses to display its most indelible mark of distinction. Free agency may have been a boon to players, but it’s also meant less sticking around long enough to cement the kind of bond that leads to a team retiring a number.

You know who were outstanding pitchers active at some point in the National League between 1984 and 1994? To name a few, there were Joaquin Andujar; John Tudor; Doug Drabek; Charlie Hough; Rick Reuschel; Mario Soto; Rick Sutcliffe; Dennis Martinez; Tom Browning; Orel Hershiser; Vida Blue. None of them has a number retired by a major league franchise. It doesn’t make any of their careers less excellent in retrospect. At their best, each of them was a tough son of a gun, and I know I never relished the prospect of Mets batters facing any of them.

Dwight Gooden pitched against each of them, however, and I would take Dwight Gooden over every single of one of them, just as I took Dwight Gooden over every single of them when he faced every single one of them. Until we knew 16 would be looking down from the left field corner of Citi Field, those guys qualified as the de facto peers of Dwight Gooden. Really and truly good, just not considered among the very, very best by some team entrusted to pass judgment on whether they were among that team’s best ever.

There was the level of talent and accomplishment exemplified by pitchers of that ilk, and then there was the level above it. In slightly more that one out of every ten of his Met starts, 31 times in all, Dwight Gooden went up against a guy from that tier: a starting pitcher who eventually did have his number retired by somebody. In chronological order of the first time Gooden faced them, that circle includes:

Nolan Ryan

Fernando Valenzuela

Mike Scott

Steve Carlton

Jerry Koosman

Dennis Eckersley

T#m Gl@v!ne

Don Sutton

Greg Maddux

John Smoltz

Pedro Martinez

Those are all great pitchers, but a caveat applies here. Few of these pitchers were at their apogee when they swapped half-innings with Doc, and not every one of these pitchers had his number retired by the team he pitched for when Doc was his mound opponent. Koosman, for example, was in his last go-round, as a Phillie, wearing a number, 24, that we don’t associate him with at all. We know him as No. 36 for the Mets, an identity reinforced when that very number was added to the Met pantheon in 2021, a sign that the Mets were doing their own bit of bending, rewriting or casting aside “rules” because they knew in their gut that Kooz, who won more games for the Mets than anybody not named Tom Seaver or Dwight Gooden, belonged up there.

Jerry was of the same generation as Ryan and Carlton and Sutton, all coming along in the 1960s. Eckersley, who’d succeeded as a starter but excelled as a reliever, was a product of the 1970s, the same decade that offered a first rough (if not yet sandpaper-rough) glimpse of Scott. Valenzuela preceded Doc to the majors by four seasons, coming up in late 1980 and inspiring a mania all his own in 1981. Maddux, Gl@v!ne, Smoltz and Martinez all debuted during the Doc sequel years. The box scores confirm that every one of them was, for at least a spell, a contemporary of Gooden’s. Steve Carlton goes back so far that the Polo Grounds still stood when he signed his first pro contract. Pedro Martinez is recent enough that he pitched at Citi Field.

Yet, regardless of date of birth or date of debut or date of last pitch thrown, none exactly strikes me as a peer of his, and I think I understand why. Because as a Mets fan who lapped up every thing Doc did in 1984 and 1985 and doesn’t disown his performance from the other years, I believe Gooden had no peers. He was Doc. He was ours. He was the best when he was doing what he was doing, especially but not exclusively at the outset. In my heart, Doc was never anything less than a blockbuster.

Those mound opponents of Doc’s, the ones with their numbers retired by somebody, were absolutely some of the best of their time, maybe all time. Eight of them have their names on the kind of plaque Dwight Gooden will likely never have. Yet I took Doc over every single of them when Doc faced them, and I would take Doc over single one of them in the abstract, even the ones whose résumés lapped his.

I’d take Doc over any pitcher he ever faced, which in the days Doc was pitching for the Mets meant only pitchers who pitched for other National League teams. From 1984 to 1986, prime Gooden time, one pitcher who certainly belongs atop any list of greats from any era happened to be finishing his career in the American League, first with the White Sox, then with the Red Sox. There was no head-to-head between Doc and him, thus no reason to envision a contemporary mound duel for the ages. Still, I have to ask myself one more question, one I can’t look up on Baseball Reference:

In the abstract, would I take Doc Gooden over Tom Seaver?

Answer: I don’t have to. Sunday will make official what we’ve known in our collective gut for nearly forty years. There’s Tom, then Doc. There’s no taking one over the other, because they go together. If you’re not feeling it in your gut, get a gander at 41 and 16. From now on, you’ll know precisely where to find them both.

I was there that Friday night, SEP07/1984 when Gooden threw that 1-hitter against the Cubs, who we were battling for the pennant.

Doc was super that night, and I finally thought we were going to get that no-hitter we were waiting for “all these years.”

Moreland hit a slow grounder toward the 3B bag in the 5th inning, and Ray Knight didn’t make the throw against the slow-footed Moreland. Another look 40 years later (the game was on regional NBC, not sure why/how) shows a tough play, and perhaps Knight’s vertigo had some effect that night.

Whatever, Cub-Busters and no-hitters were not meant to be that year.

Glad to see them finally retiring all Felix Millan’s numbers, my favorite Met of all time.

He wore 16 in 1973 and 17 from 1974-1977.

BTW, you can hear (on YouTube) the entire RADIO broadcast of the game from AUG 1977 where Ed Ott bodyslams Millan and ends his Major League career.

Lindsey Nelson was broadcasting solo, and obviously did not have a TV monitor in the radio booth, because he did not really have a clue as to what had actually happened.

It was only in the next inning when Bob Murphy took over on radio, that Murphy fully described what had actually happened. He had been doing the TV side.

I watched that game live on Channel 9, and can still see to this day Felix squirming as he is being lifted and deposited by Ott.

I remember the Ott game like it was yesterday. Was at my grandmother’s. I was apoplectic, screaming at the TV. Everyone came running in wondering what horror had me shrieking like a banshee.

Is there an unwritten rule that you can’t retire numbers on a Tuesday? Because then they could have retired #16 on the 16th.

Wonderful piece Greg. Thank you for the tip of the cap to Dana. I remember the Hofstra conference so well. Especially meeting Bud Harrelson (May he rest in peace ) who was just as wonderful as my nine-year-old’s crush remembered.

I met Doc a few years after that. He was a bit shaky, clearly still working on his recovery. He was hardly the formidable presence he was on the mound or staring down on us from the mural on 42nd St. But it made me love him more because he was so human, very sweet. I love that the Mets are honoring him and I love seeing how well he is doing now. I love reliving his greatest moments today. Just wish Dana was with us to enjoy it!

The ultimate link between Seaver and Gooden was August 4,1985, smack in the middle of Doc’s brilliant Cy Young season. That was the day Seaver won his 300th at a Yankee Stadium overtaken by Mets fans (on what was nominally, at least, Phil Rizutto Day!) and several hours later Gooden won after joining his teammates watching Seaver’s historic win. What a day for Mets fans! I remember that feeling of a torch being passed from one ace to the other, with Doc onrushing towards his destiny, and Tom indelibly stamping his ticket to Cooperstown, but on that day, even though neither Tom nor Dwight was pitching at Shea, everything was coming up Mets.

Greg, here’s another connection between my alma mater, Hofstra and the Mets. Ken Singleton spent a year as a Hofstra student, at the same time I was there, before being drafted by and eventually playing 2 years for the Mets.

I loved Seaver so much that I openly wondered who I would have rooted for had he faced us in the World Series. Pretty sure the Mets would have won my affections, though I wouldn’t have minded a game like the Doc/Ryan game at Shea a week earlier. Glad I didn’t have to find out, that would have been awful.

Younger fans who thrilled to “Harvey Day” and Jake’s starts would be amazed at the electricity when Doc pitched. Man, he was something. I was away at college in PA and even the Phillies fans who hated us wanted to watch the Gooden starts.