I wish I had brought some string with me. An enormous spool of string. Had I, I could have offered some to each player I saw in the Shannon Forde Press Conference Room Sunday morning and asked him to align himself just so in order to form the most Amazin’ live-action Immaculate Grid you could ever hope to see.

Mike Torrez of the Mets in 1983 and 1984, you also played for the Cardinals and the Expos and the A’s and the Orioles and the Red Sox and the Yankees. Please stand in the upper left.

Gary Sheffield of the 2009 Mets, you came up with the Brewers and preceded to touch down with the Padres, Marlins, Dodgers, Braves, Yankees and Tigers. Would you mind heading over to middle-right?

Barry Lyons, whose Met service spanned 1986 to 1990, I know you have some Dodgers, Angels and White Sox on your ledger. You’d go great in the bottom row, thanks.

Mookie Wilson was a Blue Jay; Roger McDowell a Phillie, a Dodger, a Ranger and an Oriole; Rafael Santana a Cardinal, a Yankee and an Indian. If I needed a Met who was a Pirate, I had Lee Mazzilli. A Met who was a Twin? There’s Tim Teufel. Met-Rockie or Met-Cub? I could use Howard Johnson. Would Sandy Carter mind standing in for her husband Gary if a Met-Giant was necessary? Wait, I could use Darryl Strawberry there. And I could use Jesse Orosco practically anywhere.

I could have done this all day, but putting baseball players in a box was not why I was there or they were there. This was about a round icon for a true icon, a circle with a 16 in the middle of it, and teammates who were happy to revolve around the man who it represents.

This was number-retirement day for Dwight Gooden, better known as Doc, only known as Doc, based on how he was addressed and referred to. That’s how it is with teammates, fans and onlookers who like to think they know what’s what. I was in the latter category most of Sunday, a media member by my credential, though a fan through and through. There’s Doc! There’s Straw! There’s Mazz and HoJo and, yeah, that’s Sheff! It’s hard to believe people bother with given names in real life.

Doc was real life for us from 1984 to 1994, as unreal as he could be on the mound for the first phase of that tenure. He hadn’t thrown a pitch for the Mets in thirty years as of Sunday. He’d been waiting for Sunday for thirty years as of Sunday, not so much to be the center of attention, but, as he said in the morning, to “make it right” between himself and the fans.

I think he did right by us.

Later he would stand stand amid an ill-timed shower in short center field, ignoring the gusts and speaking through the irony of how a little rain must fall on all our lives, even those who seem to have the world in their right hand. He reminded everybody who saw fit to celebrate with him that he couldn’t have done what he did without us cheering him at his best and sticking with him through everything else.

“I’m a Met, I’m a Met,” he said, a fact so nice it deserved to be mentioned twice.

Of course Doc had to clarify on that count since he also mentioned another association he had with another ballclub in town (twice), which isn’t necessarily a dealbreaker in the aftermath of anybody’s career. Torrez, Santana, Mazzilli, Sheffield, Strawberry, even the current manager Carlos Mendoza and a few of his charges…we’ll look past past identities if you come around here some more. At any rate, it wasn’t a day for recriminations, even if this day should have happened sooner than thirty years after the Mets and Doc initially “cut ties,” to use his phrase. He shared with the fans a story I’ve heard him tell in other settings, that he tried to come back to Shea as a pitcher when he thought he still had a little something left, but management rebuffed him. It was the late 1990s and the very early 2000s when he asked, twice. The Mets were doing well enough that it was a reasonable enough business decision that maybe a reunion didn’t make pitching sense. It also wasn’t that far removed from the time “business” reasons may have left a cloud over the Doc-Mets relationship.

The part that kills you is the Mets declining to do the one-day contract bit he’d requested when he was done, a ceremonial signing that would have allowed the pitcher who embodied them at their 1980s best to “retire as a Met” and get the new century off on the right foot. Teams and players of note make that kind of arrangement every now and then. It’s always a feelgood moment for all involved, a reminder that contracts and transactions are secondary to who you feel you are and how you wish to be remembered. Dwight Gooden pitched for the Yankees, the Indians, the Astros, the Devil Rays and the Yankees again. He was a Met “always,” he said. How about a gesture to make that clear to all concerned?

The Mets told him no, they weren’t going to do that. Fast-forward nearly a quarter-century and you could almost hear a mobile device ringing, and the reply when it was answered:

“New management, who dis?”

It was Steve Cohen on the line, telling Doc that No. 16 would be going up in the space Doc reserved for it back when Citi Field was Shea Stadium’s parking lot. Thus, Doc was back where he always belonged, give or take a stadium footprint. So was lots of his family, his nephew Gary Sheffield among them, along with lots of his teammates. The guys from the press conference room were on the field with him, as were Keith Hernandez and Ron Darling, who work there. Strawberry had a heart attack during Spring Training. His making it back really told you what this day meant to everybody who played with Doc.

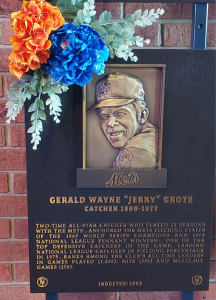

Some of these Mets from the Eighties you’re used to seeing congregating in Flushing; other than Torrez, who Doc credits with mentoring him through his first months in the majors, nobody was a complete stranger to contemporary Met environs. Yet it’s breathtaking to realize they’re right in front of you as a group. Above the stairs of the Jackie Robinson Rotunda, where the Mets Hall of Fame now lives and breathes among the fans (not to be confused with the relocated Mets Museum, which now sits in an unused wardrobe closet somewhere on the edge of Northern Blvd.), orange and blue flowers adorned the plaques of Buddy Harrelson and Jerry Grote. Buddy died in January, Jerry just over a week ago. You used to see those guys and their 1969 teammates plenty at Shea and sometimes at Citi. Only a relative few are available to visit in 2024. What I’m saying is that when World Champion Mets are around you, open your eyes and your ears and, if you’re lucky enough to be issued an official tag of some sort, your notebook.

During the press conference, where most of the players beamed proudly as they sat against a side wall (and Jay Horwitz went into PR guy mode clearing a little space between encroaching photographers and Darryl and Doc enjoying a brief chat), I asked the guest of honor what it meant to know his 16 was about to be installed next door to 24 and down the block from 41. All the Mets who have numbers retired are franchise royalty, but Willie Mays and Tom Seaver — that’s baseball stratosphere. Doc picked up on my implication, told us Tom was “a friend of mine” and that he got to know Willie “a little bit,” too, but to him, an honor like this is “for all of us”. For Keith. For Ron. For Darryl. For everybody on that wall over there, especially for the 1986 crew, including the 1986 Met who is no longer with us. Or as I overheard Sandy Carter say later, “I know Gary’s with us in spirit.”

After Doc moved on to other pre-festivities obligations, media was invited to spend time with Doc’s teammates, most of whom helpfully hung around to be pestered by the likes of me. As baseball’s particular attention to uniform numbers provided the excuse for us to have been here in the first place, I sought out Rafael Santana and asked “Raffy” (it seemed the thing to call him) about his relationship with Buddy, the man who coached him and shared 3 with him. Raffy told me Buddy was not only a great help to him but that when Raffy asked if he could give 3 back to him — Harrelson had been managing in the minors when he was installed as a lieutenant of Davey Johnson’s — Buddy told him, no, it’s more important that you have your number now, and the third base coach was fine wearing 23 in ’85 and ’86. Raffy affirmed it was meaningful to him to be in the exclusive club of two, Harrelson and Santana, who could say they were the shortstops on the diamond when the Mets became world champions.

Offering numbers to those who used to have them was a resonant subject. Doc asked Mazz, upon his return from Pittsburgh in 1986, if he wanted 16 back. Mazzilli was a big deal as 16 in Queens pre-Gooden, but Lee demurred, telling Doc it was his now. For that matter, none other than Whitey Ford let Doc know in 1996 that if he wished to wear 16 with his new club, he’d OK the Yankees unretiring it for him. That’s how big a deal Doc had always been in New York (and how much of a mensch Whitey Ford was). Doc couldn’t say yes to that.

“Respect for those people who came before you” was a theme that surfaced when I asked “Rog” McDowell about the number he wore, which, as I pointed out to him, we’d be seeing plenty the next day, Monday, April 15. Jackie Robinson Day was coming and every Met and every player in the major leagues would wear 42. I told him that every year on this occasion Mets fans like me couldn’t help but think of him, of Butch Huskey, of Ron Taylor, of the late Ron Hodges. McDowell definitely appreciated the connection, and it didn’t take Bud Selig’s declaration that 42 would be retired for everybody everywhere in 1997. Sure, he wore 42 simply because it was the number “Charlie Samuels gave me,” but he understood whose it was long before he and Doc were drafted together to be Mets in 1982.

Roger explained his father instilled in him that respect for those who preceded him, and that Mel Allen taught him history lessons on This Week in Baseball. The show and the homegrown curiosity sent young Rog to the local library to check out books on Jackie Robinson (and Ted Williams, Tom Seaver, Carl Yastrzemski and Babe Ruth as well) to learn all he could about the endeavor he would someday enter. He knew about Jackie at UCLA. He knew about Jackie in the military. Fans, he says, sometimes ask him to adorn his autograph with his number. Roger told me he’s “hesitant” to do so. It’s Jackie Robinson’s number.

I didn’t get a chance to ask Mookie Wilson anything, but I did hear him say that thing that all retired ballplayers seem to say when they talk about getting together with old teammates: “the lies get bigger” as the years go by. It’s always said with a chuckle, much as the observation of veteran players that younger players don’t sit around and talk about the game like we used to do is inevitably uttered with an undercurrent of scorn. No scorn on Sunday, though. Doc appeared happy and incredibly relaxed. Happy is understandable. Relaxed was a little surprising. Doc never wasn’t courteous to the press or anybody in a public setting, but the kid who was dealing with an army of microphones and cameras from age 19 on endured the attention in his youth as if he wished he could squirm away from it all. We know from the detours his life took that it probably wasn’t the ideal way for a young man to transition into full adulthood. On the cusp of 60, maybe it shouldn’t be surprising that Doc Gooden showed up Sunday as the old pro, as polished as a Seaver or a Mays in elder statesmanship, but we still reflexively think of him as being 20 winning 20. He seems to be winning his days nowadays. Those are the victories that count most going forward.

After the ceremonies and a 46-minute rain delay, the sun came out and the Mets won a game that you figure can’t but help them going forward.

It certainly couldn’t hurt.

You couldn’t miss Jose Butto paying proper homage to Dr. K with no runs and nine strikeouts in six innings.

You would have preferred KC’s Cole Ragans didn’t nearly match him by fanning eight and allowing nothing of consequence in six and therefore keeping the scoreboard a little too immaculate.

You were grateful to recently dormant Adam Ottavino and Brooks Raley for keeping Royals bats waving at air (2 Ks each in an inning apiece).

You were delighted that Francisco Lindor, in his long-term bid to join Buddy and Raffy as Met shortstops who will one day reunite with his world champion teammates, processed the standing-ovation encouragement the crowds are giving him into a couple of base hits.

You were relieved, despite lingering distaste for Kansas City’s misdeeds in New York in the fall of 2015, that the last of those world champion Royals still on these Royals, Salvador Perez, was able to stand up after a slam-bam play at the plate, even if the venerable backstop had to exit the action.

You were, if you were of my vintage, very much into hearing hits from the ’80s on the PA all day, a perfect accompaniment to a day devoted to a pitcher who prevented hits in the ’80s.

You were, if you were stoically pro-Mets while behaving yourself in the press box, quietly ecstatic that an eighth-inning rally built mainly on walks and punctuated by ex-Yankee Harrison Bader’s infield squib turned into two Met runs, literally enough of a cushion for trumpets to blare and Edwin Diaz to convert a save opportunity.

You weren’t really worried when Diaz gave up a solo home run with two outs. Really you weren’t. Edwin got the last out and we had a 2-1 Mets triumph over the Royals that was the only fitting way to cap off a day such as this. It didn’t alter the result of the 2015 World Series, nor did it instigate a cosmic do-over that would have had Doc facing Bret Saberhagen in Games One, Four and possibly Seven of the 1985 World Series, but we got a win on the field and a 16 in the rafters.

When you get a day like this, its rarity score is off the charts.

Doc overcame his demons and lived to get his just due on a magical Sunday.

’84 and ’85. Doc owned the Apple.

So glad there’s a happy ending for Doc’s baseball story. Anyone with a heart can’t help but shed a tear at the arc of Dwight Gooden’s story.

A good series win, but really frustrating leaving 12 men on base and going 1-9 with RISP. Danger, Will Robinson…

The only fear that existed in Flushing when Doc took the mound was in batter’s eyes and hearts. And all Mets’ fans had faith that Doc, having overcome his demons, would one day be back, looking like he could strike out the side if he chose to pick up a glove and ball.

Greg’s tribute was, as always, brilliantly spot on.

Fear not, Mets’ fans, because we have faith that, when Mets’ history is at stake, our favorite blogger will always be there to remind us of our lives when we were all young and anything was possible— especially a Mets’ win when Doc was on the mound.

[…] figuring has been exclusively on the Mets’ side since Doc Gooden’s 16 was unveiled in the Citi Field rafters and has calculated to their benefit almost without pause since Pete […]