Maybe Billy Joel’s Brenda and Eddie could never go back to the green, but I have no compunction about returning to scenes from my own fields of reality. Therefore, I welcome you anew to MY FAVORITE SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT, a series counting down just what the title implies. I started this endeavor at the very end of calendar year 2023; continued it for the balance of what remained of the last offseason; took it into Spring Training; and then paused it when the PRESENT encroached on my ruminations.

The PRESENT, in the form of 2024’s Met campaign, carried the potential to complicate matters in terms of my rankings. I had a very definite 55-through-1 order I was working my way up when I stopped at No. 12 in late March to concentrate on Opening Day and the days to come. No biggie, I figured as 2024 got going, because it didn’t appear any great personal revelations would sprout as a result of what the 2024 Mets were up or, more likely, down to. I’d get back to my rock-solid list after the regular season and smush the most recent edition wherever it fit, presumably somewhere in Also Ran Land, hopefully not compelling me to messily rearrange my bottom rung. I figured the season then in progress would rate not much more than a footnote to this entire endeavor.

But then, OMG, 2024 became TWENTY TWENTY-FOUR and may have upended some calculations. Stimulating to live through. Discombobulating to reflect upon in FAVORITE SEASONS context. So here’s my plan: proceed from No. 11 forward as anticipated, then circle back to figure out where the last Met season — a Met season like no other — fits into my scheme of things.

That bit of housekeeping attended to, I bring you below another Met season that was also like no other. That’s a trick designation, because all Met seasons are unique, surface similarities notwithstanding. How they live on in the consciousness of a particular fan is where the singularity comes to play.

April has been cited traditionally in baseball circles as a month when you shouldn’t necessarily believe your eyes, usually as it pertains to rookies who are the personification of a small sample size. The same applies to teams who stumble or surge out of the gate. If you want to sound sophisticated, say something like, “Let’s see where they are in June.” By June, the thinking goes, you know what you’re looking at.

Come June of one particular year, I saw what I wanted to see, maybe needed to see. Give me a little leeway with the calendar (lop a few days off the front of June, annex a couple of scoops of July), and in the course of my Met-loving existence, I can declare it a month for the ages in what turned out to be the year of a lifetime.

One of them, anyway.

If the assignment is to illustrate myself being a Mets fan at any time, in any place when and where I’ve been a Mets fan, I could pick a lot of times and a lot of places, as could you. But I couldn’t go wrong with a self-image that warms me all over.

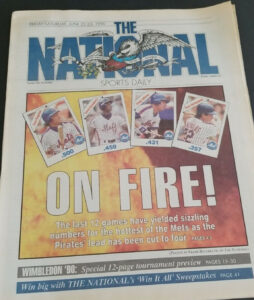

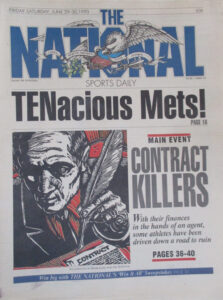

It’s late June 1990. It’s morning. It’s sunny. It’s hot. It’s after I drop my fiancée off at the train station, before I head home to get myself ready for work. It’s imperative that I stop for the papers. The Mets have won last night. The Mets have been winning every night. The Mets are on what will become an eleven-game winning streak. I park on our town’s main drag in a spot that I infer isn’t quite legal, but I’m only gonna be a minute. I run into the let’s call it candy store, though maybe it’s a cigar store or for that matter a luncheonette. I never stick around more than the length of the transaction, scooping up the News, the Post, Newsday, maybe the National and paying. Back in the car, back to our apartment, up to the kitchen table for a few minutes of soaking in another Mets win.

It’s late June 1990. It’s morning. It’s sunny. It’s hot. It’s after I drop my fiancée off at the train station, before I head home to get myself ready for work. It’s imperative that I stop for the papers. The Mets have won last night. The Mets have been winning every night. The Mets are on what will become an eleven-game winning streak. I park on our town’s main drag in a spot that I infer isn’t quite legal, but I’m only gonna be a minute. I run into the let’s call it candy store, though maybe it’s a cigar store or for that matter a luncheonette. I never stick around more than the length of the transaction, scooping up the News, the Post, Newsday, maybe the National and paying. Back in the car, back to our apartment, up to the kitchen table for a few minutes of soaking in another Mets win.

So much of what it was like to be me at a given moment crammed into one paragraph.

It’s late June… My mother died on June 17, almost two years after her chronically bad back acted up beyond the usual discomfort and indicated something worse was happening. It was cancer. The end was in sight by February 1990. That the end was a blessing in its way didn’t make it any less of an end. Her funeral was on June 19. Those she was survived by — her husband, her children, their significant others — sat shiva for visitors that night and two more. I went back to work before the week was out. Sitting around being sad wasn’t accomplishing anything. “Things’ll go your way,” Wilson Phillips advised me as I pulled into my company’s parking lot, “if you hold on for one more day.”

I drop my fiancée off at the train station… I slipped a ring on my girlfriend’s finger the previous September. Then she slipped back to college for the completion of one more academic year. Those long months wound down just before April became May. I flew down to Florida, helped pack her up, watched her graduate, and flew her to our new home. She’d never seen it before and neither of us had ever spent a night there. Yet she was all in. Within a matter of weeks, she’s lined up job interviews. She nails one by mid-June. They ask her if the death of her fiancé’s mother means she’ll need more time before starting. I tell her the active mourning period will expire conveniently. Her first day as a case manager tending to an elderly population on Manhattan’s Upper East Side is June 25. I drop her off for the LIRR, something she’s ridden before, but not to work. Just like that, barely two months removed from student life more than a thousand miles away, my intended is a daily commuter in the Greater New York Metropolitan Area. She’s 22.

Get myself ready for work. I’m 27. I kind of futzed around when I was 22, 23. The Mets were winning. I barely noticed anything else. At 24, I met Stephanie. Engagement was made official the September I was 26, when I’d been holding my first true full-time job for about six months. I needed to do something to afford a (humble) ring let alone that (humble) apartment that would set the stage for our life together. By June of 1990, it’s a comfortable enough situation careeerwise. Probably too comfortable. I’d begin to get a little sick of what I was doing — writing and editing for a trade magazine on Long Island — fairly soon, but not sick enough to do anything about it. Roughly every two years I’d have had enough, then have some more. Comfortable can be comforting when things around you are changing fast. My mother is gone. My fiancée is here. We’re living in this new place, which would require several rounds of moving. The people at work are very understanding when I need a few extra days in the first half of 1990 to take care of personal business. Nobody says anything if I show up at whatever time I do because I needed a few extra minutes to read the papers each morning.

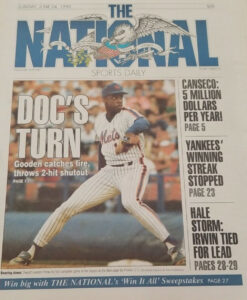

The papers… What else was I going to read if I wanted to dive deep into what was going on with the Mets in June of 1990? Later in the year, Goodfellas came out and the character I related to most was Jimmy Two Times, the wise guy who said everything twice. He was the one who said he was gonna go get the papers, get the papers. That was me, times two. Get the News. Get the Post. Get Newsday. Get the National, even. Tabloid sports section heaven. The National, new in 1990 (and gone by 1991), was nothing but a sports section. They were all essential when the Mets were in season. How else would I know what One Met Said when the Mets were losing? How else would I get a feel for what was going right when the Mets were winning? Looking at your phone in those days meant staring at it waiting for it to ring, and it’s not like Bob Klapisch was calling you personally.

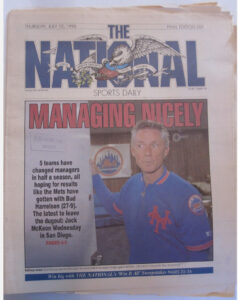

Eleven-game winning streak… Holy crap, the Mets were literally unbeatable. It wasn’t the first time the franchise had gone that long impervious to defeat; eleven was the record set when the 1969 Mets (rising from 18-23 to 29-23) awoke to the possibility that their perpetual lot wasn’t to be a punch line or punching bag, and it was tied in promising 1972 (surging from 14-7 to 25-7) and again in powerful 1986 (shaking off 2-3 to all but clinch the division at 13-3 before May arrived). But the timing here was most impeccable. The 1990 Mets had stumbled through April and May, unbecoming of their perennial contender status. At 20-22, they cost Davey Johnson, their most successful manager ever, his job. They bottomed out at 21-26. Longtime aide Buddy Harrelson, eternally a Met, except when he was passing through the Phillie and Ranger clubhouses — and maybe even then — was now steering the ship, but the early returns weren’t indicating smooth sailing was ahead.

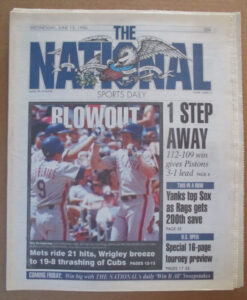

Then…ahoy, Metsies! On June 5 at Shea, Kevin McReynolds ties the Expos in the eighth with a two-run homer, and come the eleventh, it’s benchwarmer Tom O’Malley taking Dale Mohorcic deep to win the game and light a fuse. The Mets, stuck in fourth 8½ back, go on a 9-3 roll. The offense explodes, especially in Chicago, where we win 19-8, then 15-10, then 9-6. The wind really knew how to blow out in those days.

Then…ahoy, Metsies! On June 5 at Shea, Kevin McReynolds ties the Expos in the eighth with a two-run homer, and come the eleventh, it’s benchwarmer Tom O’Malley taking Dale Mohorcic deep to win the game and light a fuse. The Mets, stuck in fourth 8½ back, go on a 9-3 roll. The offense explodes, especially in Chicago, where we win 19-8, then 15-10, then 9-6. The wind really knew how to blow out in those days.

Somehow winning nine of twelve is tantamount to a throat-clearing exercise. In full voice, the 30-29 Mets proceed to win eleven in a row and become the 41-29 Mets. It begins in Pittsburgh, which is important, since they’ve assumed control of first place and therefore require catching, and it begins on June 17, which is important to me, because that’s the day my mother died. The game was over before she breathed her last. Doc went seven, struck out eight and pulled the Mets to within six. The News made much of the Three Rivers speed gun saying Doc’s fastball touched 100 MPH, a Gooden first. Doc, along with Keith, ranked as my mother’s favorite Met. She didn’t make lists like I did, but I could tell. Keith had moved on to Cleveland. Doc was still here for us, firing faster fastballs than ever, and evening his record at 5-5.

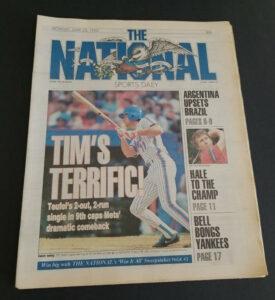

Then ten more Met wins in a row. Five at home, the spine-tingliest among them secured on a Sunday afternoon when Tim Teufel pinch-singled in the tying and winning runs in the bottom of the ninth off Roger McDowell. Three in St. Louis, including another eleven-inning thriller in the middle of the set (John Franco blows the lead in the ninth by allowing a leadoff homer to rookie catcher Todd Zeile, but HoJo comes through with a two-out, two run double to make the streak eight straight). Then back to Shea to take one on a Thursday night from supposedly unstoppable Cincy — they were going wire to wire in the West — and then another on Friday night. Bobby Ojeda scattered ten hits to secure that one, the eleventh consecutive New York victory. It vaulted us three percentage points ahead of the Pirates. Pittsburgh’s one ahead in the win column, but we’re one ahead in the loss column, because we have stopped losing.

Then ten more Met wins in a row. Five at home, the spine-tingliest among them secured on a Sunday afternoon when Tim Teufel pinch-singled in the tying and winning runs in the bottom of the ninth off Roger McDowell. Three in St. Louis, including another eleven-inning thriller in the middle of the set (John Franco blows the lead in the ninth by allowing a leadoff homer to rookie catcher Todd Zeile, but HoJo comes through with a two-out, two run double to make the streak eight straight). Then back to Shea to take one on a Thursday night from supposedly unstoppable Cincy — they were going wire to wire in the West — and then another on Friday night. Bobby Ojeda scattered ten hits to secure that one, the eleventh consecutive New York victory. It vaulted us three percentage points ahead of the Pirates. Pittsburgh’s one ahead in the win column, but we’re one ahead in the loss column, because we have stopped losing.

And doesn’t the East know it?

METS VS THE DIVISION, June 5, 1990 – June 27, 1990

vs Montreal 2-0

vs Pittsburgh 5-2

vs Chicago 3-1

vs St. Louis 5-0

vs Philadelphia 3-0

Over a 32-game span that also incorporates interactions with the Reds (4-1), the Astros (2-0) and the Braves (3-1), we go 27-5. None of those five losses are back-to-back. It remains the longest stretch in Mets history to encompass only five losses. The Mets were never better over a 32-game span than they were between June 5 and July 12 of 1990. Baseball success isn’t usually measured by 32-game spans, but this one deserves its props. In the equivalent of one-fifth of a season, the Mets play at an .844 pace. That’s a 137-25 record extrapolated over 162 games.

You can extrapolate to your heart’s content, but what happens on the field and how it lands in the actual standings is what counts, and that’s where 1990 drifts off toward the rocks again. It was a massive haul to rise to a virtual tie for first place as June was becoming July. So many Mets were so incredible for more than a month. Gooden kept winning. Frankie “Sweet Music” Viola kept winning. They were backed up by Coney (when he wasn’t arguing with umps while runners crossed plates) and El Sid. Bobby O was still capable of pitching a club into first place. Ron Darling was present as a reluctant recast swingman, though as a broadcaster he seems to prefer to forget he was ever a Met in the 1990s. I missed Randy Myers, who was Nasty in Cincinnati, but John Franco, for whom Randall K was traded the prior December, was born to be a Met, and now he finally was. Between Frankie and Johnny, the postgame interviews never sounded so authentically New York.

You can extrapolate to your heart’s content, but what happens on the field and how it lands in the actual standings is what counts, and that’s where 1990 drifts off toward the rocks again. It was a massive haul to rise to a virtual tie for first place as June was becoming July. So many Mets were so incredible for more than a month. Gooden kept winning. Frankie “Sweet Music” Viola kept winning. They were backed up by Coney (when he wasn’t arguing with umps while runners crossed plates) and El Sid. Bobby O was still capable of pitching a club into first place. Ron Darling was present as a reluctant recast swingman, though as a broadcaster he seems to prefer to forget he was ever a Met in the 1990s. I missed Randy Myers, who was Nasty in Cincinnati, but John Franco, for whom Randall K was traded the prior December, was born to be a Met, and now he finally was. Between Frankie and Johnny, the postgame interviews never sounded so authentically New York.

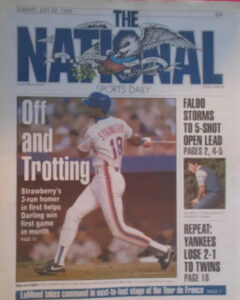

Daryl Boston, who started the year on the White Sox, and Mark Carreon, who started the year on the bench, shared center to exquisite effect. Jefferies, HoJo, K-Mac, Mackey the Slasher, Dave Magadan who made Mike Marshall superfluous, and the crown jewel of the operation Strawberry combined to slug like crazy. Darryl, eight seasons into a career that had been outstanding but never quite brilliant enough to satisfy us fully, was, at last, everything we’d dreamed he’d be when he was drafted out of Crenshaw High a decade before. Made the cover of Sports Illustrated and marked the occasion by banging one off the Shea scoreboard (Boston went nearly as deep in the same inning, two months after Newhart — featuring two brothers named Da(r)ryl — aired its finale).

Amid this 32-game stretch of 27-5, Strawberry’s individual offense was nearly as unbeatable: 14 homers, 36 ribbies and a .377 average. His OPS, whatever that was in pre-analytics 1990, measured 1.248. Straw was also rounding into form just in time for free agency. Cashen wouldn’t let him go, right? Hmm…Cashen let Davey go, and Davey was the winningest manager we’d ever had, just like Darryl already held the Met career record for home runs. Davey didn’t deserve canning, but you couldn’t complain about a thing Buddy was doing at the helm. He was, apparently, just what these Mets needed.

Amid this 32-game stretch of 27-5, Strawberry’s individual offense was nearly as unbeatable: 14 homers, 36 ribbies and a .377 average. His OPS, whatever that was in pre-analytics 1990, measured 1.248. Straw was also rounding into form just in time for free agency. Cashen wouldn’t let him go, right? Hmm…Cashen let Davey go, and Davey was the winningest manager we’d ever had, just like Darryl already held the Met career record for home runs. Davey didn’t deserve canning, but you couldn’t complain about a thing Buddy was doing at the helm. He was, apparently, just what these Mets needed.

And these Mets were, apparently, just what I needed. In the nautical terms I’m suddenly fond of, they kept me anchored. So much transition swirling around me in so-called real life, yet here were the Mets, just as much a part of my existence as ever. There for me in a summer of loss, a summer of discovery, a summer of settling in, a summer of absorbing every word and statistic the papers printed about my Mets. Not only my Mets in name and logo, but my Mets who were permanently (since 1984, at least) competing for a championship. Finished first twice in the previous six seasons. Fought for first four other times, finishing second but knowing we should have been first. We were fighting to get where we belonged again. Playing badly enough in April and May to get their skipper tossed overboard was the aberration. Full speed ahead was more like it.

It’s what the Mets had been like every season since they straightened themselves out. Since Doc. Since Darryl. No more Keith or Gary (or Mookie or Lenny or Wally, either), but wasn’t this how it was supposed to work? I grew into new circumstances as the ’80s became the ’90s. So did the Mets. Doc and Darryl were veterans. Other youngsters had been cultivated in their wake as the 1980s continued. Like Cone, who zipped from representing pitching inventory in ’87 to winning twenty games in ’88. Like Elster, who set an errorless streak record for shortstops in ’89. Like Magadan, whose ascent to the everyday lineup revealed a .328 hitter who was just waiting for his opportunity. Like Jefferies, the perceived problem child who had no problem when it came to doubling (he would total a league-leading 40 two-baggers by season’s end). They were all younger than thirty. They were all in or approaching their prime. The Mets as a year-in, year-out factor were built to last. Competitive sustainability that transcended players aging out or passing their peak was the beau ideal of baseball, and here it was, coming to fruition in Flushing four years after 1986.

It’s what the Mets had been like every season since they straightened themselves out. Since Doc. Since Darryl. No more Keith or Gary (or Mookie or Lenny or Wally, either), but wasn’t this how it was supposed to work? I grew into new circumstances as the ’80s became the ’90s. So did the Mets. Doc and Darryl were veterans. Other youngsters had been cultivated in their wake as the 1980s continued. Like Cone, who zipped from representing pitching inventory in ’87 to winning twenty games in ’88. Like Elster, who set an errorless streak record for shortstops in ’89. Like Magadan, whose ascent to the everyday lineup revealed a .328 hitter who was just waiting for his opportunity. Like Jefferies, the perceived problem child who had no problem when it came to doubling (he would total a league-leading 40 two-baggers by season’s end). They were all younger than thirty. They were all in or approaching their prime. The Mets as a year-in, year-out factor were built to last. Competitive sustainability that transcended players aging out or passing their peak was the beau ideal of baseball, and here it was, coming to fruition in Flushing four years after 1986.

But the .844 pace was unsustainable. Come across any 137-25 teams in your travels lately? More concerning in the moment was the Pirates were proving naggingly indefatigable. Our .003 lead on June 29 — I can still see the standings in our neighborhood Friendly’s house copy of Newsday I couldn’t take my eyes off between patty melt bites — didn’t serve as a launching point to blow away our competition. Our winning streak ended, but our general roll extended: five more in a row, seven out of eight, including the opener of a twi-nighter at Riverfront that got us to 48-31 directly after the All-Star break. But we dropped the nightcap, and the Pirates persevered past the Padres in fifteen. As of the close of business on July 12, we sat a game behind the Buccos. We’d gone 27-5, yet it didn’t earn us as much as a share of first place. We’d made up an ocean’s worth of ground since Tom O’Malley struck lightning, but not enough to compensate for the inevitable market correction.

Friday the 13th brought a second consecutive loss for the first time in seven weeks. The Mets dropped three of four in Cincinnati, then two of three in Houston. Winning returned to habitual if not constant (including a night at the Vet when a 10-3 laugher became a 10-9 nailbiter of a damn thing), and the Mets passed the Pirates for a few days here, a few days there, but there was no shaking the newest NL East nemesis. Slumps and injuries crept back in the picture. Mackey Sasser, who was always more about hitting than catching (or throwing) was never the same after getting bowled over at the plate in Atlanta in early July. Kevin Elster went out for the season in early August with a torn labrum in his right shoulder. There went dependable defense up the middle.

Friday the 13th brought a second consecutive loss for the first time in seven weeks. The Mets dropped three of four in Cincinnati, then two of three in Houston. Winning returned to habitual if not constant (including a night at the Vet when a 10-3 laugher became a 10-9 nailbiter of a damn thing), and the Mets passed the Pirates for a few days here, a few days there, but there was no shaking the newest NL East nemesis. Slumps and injuries crept back in the picture. Mackey Sasser, who was always more about hitting than catching (or throwing) was never the same after getting bowled over at the plate in Atlanta in early July. Kevin Elster went out for the season in early August with a torn labrum in his right shoulder. There went dependable defense up the middle.

Reinforcements shuttled in. Kelvin Torve was promoted in August and scalded the ball, wearing No. 24 until it was rightly judged a sacrilege; he was issued a less fraught set of digits. The postseason-eligibility trade deadline unveiled a pinch-hitter famous for delivering with the bases loaded, Pat Tabler, born too late to take advantage of any Golden At-Bat innovations; a new defensive specialist catcher, Charlie O’Brien (we went through seven backstops in 1990, including 1970s survivor Alex Treviño and MLBer for a day Dave Liddell); and a new middle infielder, Tommy Herr, whose participation on the wrong side of the Met-Cardinal wars of the ’80s we were willing to overlook. The answer to both Darling and Ojeda not pitching to their respective previous forms as starters was divined in the Triple-A personage of Julio Valera.

When you wish upon an unproven starter, dreams can sometimes come true. On September 1, a Saturday afternoon affair telecast to the nation by CBS, it all clicked. O’Brien caught Valera for six solid innings. Herr homered. Ojeda and Darling served as effective setup men for Franco, no matter that neither man fancied himself a reliever. Bobby O wasn’t happy: “I will do the best I can to keep my mouth shut.” Ronnie D wasn’t happy: “I am shocked. I am hurt. I never expected this.” Ultimately, Julio V wouldn’t delight Mets fans (he’d make two more starts, neither successful), but the outcome in the short term was unquestionably happy: the Mets beat the Giants, 6-5. Combined with the Pirates’ 2-1 loss in ten at Houston that night, the Mets leapfrogged into first place, perfectly positioned for the stretch drive ahead.

When you wish upon an unproven starter, dreams can sometimes come true. On September 1, a Saturday afternoon affair telecast to the nation by CBS, it all clicked. O’Brien caught Valera for six solid innings. Herr homered. Ojeda and Darling served as effective setup men for Franco, no matter that neither man fancied himself a reliever. Bobby O wasn’t happy: “I will do the best I can to keep my mouth shut.” Ronnie D wasn’t happy: “I am shocked. I am hurt. I never expected this.” Ultimately, Julio V wouldn’t delight Mets fans (he’d make two more starts, neither successful), but the outcome in the short term was unquestionably happy: the Mets beat the Giants, 6-5. Combined with the Pirates’ 2-1 loss in ten at Houston that night, the Mets leapfrogged into first place, perfectly positioned for the stretch drive ahead.

Nineteen Ninety marked the seventh consecutive year when September dawned and the Mets were no less than in it. You know…it. First place or a conceivably close second. Finish first, go to the playoffs. Finish second, go home. Finishing first was immensely preferable. Finish second, it was still quite a year, probably. But finish first, OK? Being in it is great. Being around to win it in October is the idea. I thought we’d win the NL East at the outset of September 1990. That may have been June and the first part of July talking, but I also thought we’d win the NL East at the outset of Septembers 1984, 1985, 1987 and 1989. I didn’t have to do much thinking on the subject entering September 1988 or any at all of this nature in the summer leading to September 1986. We’d had two divisions under lock and key; four going on five had been up for grabs. We’d never grabbed any of those we didn’t fully control in this era. September 1990 would have been a good time to start.

The Tommy Herr/Charlie O’Brien/Julio Valera/Pat Tabler-enhanced Mets spent three days in first place, the last three days any Mets team would spend in first place in September until the beginning of September 2000. Three golden days before the month gathered tarnish. The club didn’t exactly fall apart. There was no Terry Pendleton lurking to craft undying narratives. There were some rough losses in the moment — only true heads cringe at the invocation of Brian Barnes and Chris Nabholz — but little that echoes dissonantly down the corridors of time. The assorted letdowns of 1990 did not constitute a name-brand devastation. Conversely, the intervals when challenges were risen to stirringly have also faded from collective memory. In the middle of the Mets not necessarily getting done all that needed to get done, they did sweep a pair from the Pirates at Shea that would have fit snugly inside a sequel to A Year to Remember. The stars aligned where and how they’d been aligning since they rose for real in 1984.

Last dance…

September 12: Dave Magadan doubles into the gap to drive home Gregg Jefferies and Keith Miller in the first inning off John Smiley. David Cone makes those two runs stand up for the full nine in a gripping 2-1 decision. These were the Daves we knew. Barry Bonds surely recognized who he just went hitless against in four at-bats: “Cone pitched great, simply great. He’s a great competitor. He never gave and I don’t think he lost any velocity from one to nine.” These were the Mets we knew en masse, beating the Bucs of Bonds and Bonilla and pulling to within 2½ of first place in front of 48,375 paying customers who know a pennant race when they see one.

Last chance…

September 13: Darryl Strawberry is up in the fourth with Tommy Herr on second and Magadan on first. The Pirates are ahead, 2-0. Doug Drabek is on the mound, in search of his twentieth win. He’s not going to get it tonight, not once Darryl takes Doug deep for the three-run bomb that detonates ecstasy among 51,079. “I know Drabek is a good pitcher,” Darryl, who delivered a walkoff blast versus ace Cardinal closer Lee Smith two nights earlier and three other ribbies the night against Smith’s team the before that, says afterwards, “but man, I’m a good hitter right now.” Also a good pitcher in quite a groove is Doc Gooden, shaking off a shaky first and lasting until there were two out in the eighth to earn a 6-3 win. Doc was 3-5 when the Mets seemed to be going nowhere. He’s now 17-6, and the Mets are a game-and-a-half from first. “I pitched some great games in the playoffs in 1986 and in 1988,” Gooden reflects to reporters, “but I did not win those. This is the biggest game I’ve ever won.”

For love…

Seasons can slog too long and eras can endure not long enough. The season that launched the century’s final decade was, per the way we read calendars, not of the ’80s. It’s also not of a piece with the rest of the ’90s. In retrospect, 1990 — a year of personal reset for this Mets fan — was one big Closing Day for the era it wound up concluding. I can’t say I was sure the Mets would prevail in their pursuit of the pennant, but it didn’t cross my mind they wouldn’t. That was what that era was like, never mind all those second-place finishes that stung while they were burrowing under our skin. You didn’t believe in the Mets for golly-gee whiz rationalizations. You believed in the Mets because you believed the Mets were too good to not win.

No Mets fan who took in the depth and breadth of the victories of September 12 and September 13 would have bet against the 82-61 Mets passing the 84-60 Pirates in a matter of days. Except there were only so many days left to 1990, and Bonds was en route to his first MVP and Drabek nearing his only Cy Young, and the Mets, despite their spectacular homestand, had done too much ebbing when not flowing. Being 82-61 on the heels of a four-game winning streak was swell on the surface, but let’s remember they were once 48-31, meaning they had split sixty games from roughly mid-July to mid-September. The rest of the schedule would find momentum peeking in and out of view, only to go into hiding when you thought it was on our side to stay. There’d be games like the one against the Phillies when Tabler batted with the bases loaded and indeed drove in two runs off eventually ageless Terry Mulholland, but not enough coming through in the clutch on either side of the ball in too many other games. The Mets lost nine of sixteen after their sweep of Pittsburgh. They were eliminated while they were losing the last of them. I didn’t know that until I got off a plane in San Francisco — a conference required covering on my part — and raced to a pay phone to call home to get the score. Stephanie reported the result. Not the one I wanted to hear, but nobody I’d have rather heard it from. My fiancée, albeit by osmosis, had just experienced her first pennant race.

It wouldn’t be her last, though it would be for a while.

Darryl Strawberry took his 37 home runs, his 108 runs batted in and his penchant for meeting a moment and left for Los Angeles as a free agent in November. Stephanie broke that to me, too, and delivered the consolatory hug such a bulletin required. Darryl’s departure should have indicated the Met glory days of the 1980s were unconditionally over, but we were used to thinking big, so maybe we could get by without him in 1991. Strawlessly, the Mets hung within wishing distance of the Pirates until August before altogether collapsing. No pennant race in September. No winning record when the season ended in October. A gaudy shakeup in advance of 1992 yielded mainly embarrassment; then 1993 was somehow exponentially worse; and the next few years amounted to marginally effective damage control. The 1990s no longer bore any resemblance to the high-flying decade that preceded it at Shea, nor the year that served as its bittersweet coda.

What came after 1990 might have hit me harder than the Grant’s Tomb epoch that followed “I know, let’s trade Seaver!” because I thought we had absolute awfulness licked once the Doubleday-Wilpon-Cashen era shed its growing pains and put down roots. Seven years of pain, 1977 through 1983, were erased by seven years of plenty, 1984 through 1990, featuring one world championship and very few games when something wasn’t on the line. All good things might have to come to an end, but do they have to be shoved off a cliff? In exploring the Mets portion of David Cone’s career in A Pitcher’s Story, Roger Angell wrote, “Second place is hard country.” Try fifth, à la ’91 and ’92. Try seventh, with the expansion Florida Marlins sitting on your head in ’93. We had no inkling success would ever be out of our grasp again, let alone so soon. We had no idea we wouldn’t win more than we lost as a matter of course. We had no idea finishing a heartbreaking close second, pre-Wild Card, would seem like an accomplishment. From 1991 on and for the balance of the Nineties, such a season loomed as aspirational — an unreachable star beyond our reasonable hopes until handfuls of managers and general managers and loads of players came and went and, suddenly, the ’90s were growing late. I’d keep reading whatever was written about this team as the decade wore on, regardless of the news rarely being encouraging.

What came after 1990 might have hit me harder than the Grant’s Tomb epoch that followed “I know, let’s trade Seaver!” because I thought we had absolute awfulness licked once the Doubleday-Wilpon-Cashen era shed its growing pains and put down roots. Seven years of pain, 1977 through 1983, were erased by seven years of plenty, 1984 through 1990, featuring one world championship and very few games when something wasn’t on the line. All good things might have to come to an end, but do they have to be shoved off a cliff? In exploring the Mets portion of David Cone’s career in A Pitcher’s Story, Roger Angell wrote, “Second place is hard country.” Try fifth, à la ’91 and ’92. Try seventh, with the expansion Florida Marlins sitting on your head in ’93. We had no inkling success would ever be out of our grasp again, let alone so soon. We had no idea we wouldn’t win more than we lost as a matter of course. We had no idea finishing a heartbreaking close second, pre-Wild Card, would seem like an accomplishment. From 1991 on and for the balance of the Nineties, such a season loomed as aspirational — an unreachable star beyond our reasonable hopes until handfuls of managers and general managers and loads of players came and went and, suddenly, the ’90s were growing late. I’d keep reading whatever was written about this team as the decade wore on, regardless of the news rarely being encouraging.

I lived in 1990 and rooted in 1990 and loved this season enough during and after 1990 to identify it as a more of a personal favorite than some astounding seasons that have come along since, seasons that continued into postseason, which is the essential goal of every regular season, a destination 1990 never reached. “Favorite” is a funny word here. I can’t say I loved the outcome of 1990 more than I loved some of the seasons lined up behind it in my esteem, but I know 1990 meant too much to me as it unfolded middle out to hold its shortcomings against it. Not winning at the end doesn’t ruin everything if you’re in it for the long haul. Some years I’m in seasons as much for their Junes and Julys as much as I am for their Septembers and Octobers.

That there wasn’t much on which to hang a Mets hat in the protracted aftermath of 1990 makes 1990 stand up and stand out for me perhaps more than a fifth disappointing runner-up finish in seven years should. That it was the year that served as vibrant backbeat to our first summer in our first apartment — my fiancée and me — no doubt boosts it beyond its bottom line of 91-71, four frustrating paces behind Pittsburgh. Stephanie coming to New York was the move of a lifetime. More than Hearn for Cone. More than Allen for Hernandez, even. She embraced the Mets fandom that informed my mornings getting the papers and my nights watching to the last out and then flipping on Mets Extra for Howie Rose’s interpretation of events. She learned to discern my Metsian wails of agony from those indicating mere physical distress. I’d spent the previous six seasons utterly immersed in a ballclub that was always on the edge of greatness — one big pitch or swing would do it, I swore, and sometimes did. As a seventh coalesced, I didn’t know how to not care deeply about the Mets every single day, even with the presence of somebody else in the picture I cared deeply about making me realize I’d be loving two entities this way for as long as I lived. For better or worse, it was part of me, and not once did my future betrothed (we wedded on the second Sunday of November of 1991, the date chosen so as to ensure no anniversaries would conflict with any World Series) take stock of our shared household and act as if my attachment to baseball was something that would look better stashed in a drawer.

Then again, why would I fall in love and live happily ever after with somebody who’d act like that? And why wouldn’t I stick with a team that gave me a June and part of July like 1990’s? C’mon, they went 27-5! Twenty-seven and five! Happy endings are the best, but don’t sleep on elevated middles. They can take you places that now and then last a lifetime.

PREVIOUS ‘MY FAVORITE SEASONS’ INSTALLMENTS

Nos. 55-44: Lousy Seasons, Redeeming Features

Nos. 43-34: Lookin’ for the Lights (That Silver Lining)

Nos. 33-23: In the Middling Years

Nos. 22-21: Affection in Anonymity

No. 20: No Shirt, Sherlock

No. 19: Not So Heavy Next Time

No. 18: Honorably Discharged

No. 17: Taken Down in Paradise City

No. 16: Thin Degree of Separation

No. 15: We Good?

No. 14: This Thing Is On

No. 13: One of Those Teams

No. 12: (Weird) Dream Season

Interesting that this ranking is based on your overall experience with the season in question, as it is for each year, not merely a linear hierarchy of how many games the Mets won or how far they got in the playoffs. Your third-to-last paragraph sums up the sentiment nicely. Oh, and I particularly appreciated this phrasing: “[L]ittle that echoes dissonantly down the corridors of time.” Very evocative of image and mood. That is just one prime illustration, in addition to the Mets detail and pinpoint accuracy, of why we love reading your blog.

[…] baseball category, save heartbreak. I never have. I know recent decades indicate otherwise, butI have a functioning memory. I remember New York in 1969 and the first half of the 1970s. I remember when worms turned in the […]