“There are certain figures in American history who have passed into the realm of cultural mythology, as if reality could no longer contain their stories: Johnny Appleseed. Wild Bill Hickok. Davy Crockett. Rickey Henderson.”

—Tom Verducci, 2003

Maybe somebody else in baseball or sports or life referred to himself in the third person before Rickey Henderson made it a trademark of his conversation. But it was his public-facing trademark. Everybody else was “I”. Rickey Henderson was “Rickey”.

Rickey’s pronouns were Rickey, Rickey and Rickey’s. Being “Rickey” worked for Rickey. Rickey worked for many a team. There is no “I” in team, you’ve heard it said. When your team had “Rickey,” your team got way more interesting. We speak from first-Rickey experience.

Twenty-six years ago this month, Rickey Henderson signed with the New York Mets. The Mets bringing in an accomplished veteran from the hinterlands was nothing new. The first batter in Mets history was an accomplished veteran, Richie Ashburn. The first batter when next the Mets played would be Rickey Henderson. From Richie to Rickey…why not? Through the years (Duke Snider, Warren Spahn, Ken Boyer, Tommy Davis and so on), it was always worth a shot. Except this was different from all the for better/for worse importations of previous decorated elders. This was Rickey. Rickey was one of a kind.

Rickey had been one of a kind since ascending to the top of the Oakland A’s order on June 24, 1979. Rickey was twenty years old. He was on top to stay. He was about to start leading the American League in everything that was up his alley. Hits. Walks. Runs. Steals. Oh, the steals. Rickey Henderson’s proclivity for stealing bases made him national news. Nobody — not Cobb, not Wills, not Brock, not his less-celebrated, lower-key NL doppelgänger Raines — stole bases like Rickey. He had the single-season record wrapped up in his fourth August as a major leaguer. By his second, it was clear our beloved left fielder Steve would not be his position’s or generation’s leading Henderson.

Rickey owned every record related to Rickey reaching and Rickey running. Rickey did most of this out of a Mets fan’s view, save for All-Star games, postseason series and, when a Mets fan had nothing better to watch, those few years when Rickey was doing Rickey things in New York. If the Mets were idle, a Mets fan might glance at a Yankees game between 1985 and 1989. Rickey, Mattingly, Winfield — how did they never win anything? I mean besides because of not enough pitching?

Rickey had been traded to the Bronx from Oakland because of money. Oakland traded to get him back once they were angling for a world championship (and the Yankees hadn’t won anything). Rickey set the ALCS on fire in ’89. When the playoffs were simply division winners facing off, performances like his stayed with a temporarily affiliated viewer. The A’s were playing the Jays. The Jays had Mookie and Mazzilli, so I preferred they win. The A’s had Rickey Redux, and he made sure they won. Seven steals in the first three games. Two homers in the fourth game. A’s in five.

The next year, Rickey is AL MVP. The year after that, Rickey is the all-time stolen base champ. He passes Lou Brock again. Lou shows up to congratulate him. Rickey pays homage to Lou, then announces to the crowd that now he — Rickey — is the greatest at his core competency. It’s a little gauche. He’s not wrong.

The Nineties endure. Rickey is in and out of an A’s uniform, in and out of favor. Rickey is inevitably Rickey, which was understood. Rickey showed up in Toronto in a hot pennant race. The Blue Jays went to the World Series with him. Rickey led off the ninth of Game Six, Jays down one. Rickey walks. I’m rooting for the Phillies to hold on and force Game Seven (they have Dykstra and I’m watching with an old pal from Philly), but once Rickey walks, I intuit they’re screwed. Molitor singles. Carter homers. Rickey and the Jays are champs.

Still, you couldn’t mold him into exactly the person you wanted him to be, which crossed only the minds of those viewing from a distance, those uncomfortable with his utter Rickeyness. Singularity indicates a character who is one of one. You had to want Rickey as Rickey, which meant the older Rickey, the dinged-up Rickey (everybody else had hamstrings; Rickey had hammies), the Rickey who knew what was best for Rickey and figured out how to most optimally apply it in a given situation. Still reaching base, still taking bases.

Rickey’s not a direct concern of Mets fans until 1996 when Rickey is a Padre. The first time he faces us, he walks. Before the game is out, he singles, steals second and brings home an insurance run. Rickey leads off for San Diego throughout his age 37 season, and the Padres win the NL West. In the first game when he’s 38, Opening Day 1997, Mets at Jack Murphy, Rickey comes off the bench and homers against Pete Harnisch, part of an eleven-run uprising in which Rickey scores twice and Bobby Valentine uses four pitchers.

After a detour to Anaheim, Rickey returns to Oakland — fourth time — when he’s 39 and steals 66 bases, roughly half of the 130 he stole when he set the MLB mark in 1982. He was 23 then. He steals only half as many now? There’s a “what would Ty Cobb bat these days?” retort (“oh about .250 — he’d be over a hundred years old”) in there somewhere. Rickey shows he still has enough so that it could be discerned he’ll keep running forever.

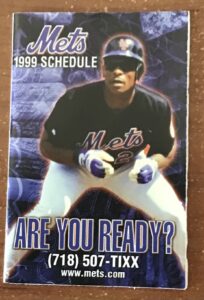

On the eve of his fortieth birthday, he takes off for Queens. In 1998, the year they almost won the Wild Card, the Mets employed ten different hitters in the leadoff slot. To upgrade for 1999, they seek stability at the top of the order. They sign Rickey Henderson, holding a press conference and presenting him a birthday cake a few days before Christmas. It is part of Rickey’s legend that he was born on December 25, Santa’s gift to the game.

On the eve of his fortieth birthday, he takes off for Queens. In 1998, the year they almost won the Wild Card, the Mets employed ten different hitters in the leadoff slot. To upgrade for 1999, they seek stability at the top of the order. They sign Rickey Henderson, holding a press conference and presenting him a birthday cake a few days before Christmas. It is part of Rickey’s legend that he was born on December 25, Santa’s gift to the game.

Rickey is Rickey as he returns to New York.

“I love to run and dive into the dirt. Age doesn’t make a difference. I said I can play until I’m 50, so I have another ten years.”

“I’m a winner. I want to be a on a team that wants to win.”

“I think the Mets have a better team because I’m coming here. It’s just the confidence I have, that anything can happen.”

“I’m hoping to create some excitement. If I steal some bases and take that attitude, I can make things happen.”

“We didn’t discuss who the No. 2 hitter will be, but I’ll say he’ll probably have a great year.”

Bobby Valentine’s two-hole hitter in 146 out of 163 games in 1999 was Edgardo Alfonzo. Fonzie drove in 108 runs. He had a great year. The leadoff hitters were mainly Rickey and his baserunning protégé Roger Cedeño, obtained from the Dodgers the same offseason. They were a good match, considering that Roger’s “hero when I was growing up was Rickey Henderson.” Between them, Rickey and Roger stole 103 bases: forty-year-old Rickey 37, Roger a new franchise record 66, or 58 more than he swiped for L.A. the year before. The 1998 Mets pilfered all of 62 bags and crossed the plate 706 times. The 1999 Mets, catalyzed by their most-everyday left fielder, increased those totals to 150 and 853, respectively.

The onslaught of offense wasn’t all Rickey’s doing, but opposing pitchers were facing Rickey (or Roger) to start every game. The opportunities awaited Fonzie, Olerud, Piazza, Ventura. Boy did that crew cash in. True to Rickey’s aspirations, excitement was created and things happened.

• April 7, Rickey’s third game as a New York Met, at Florida. Rickey leads off with a walk. He’s ready to steal. He’s picked off. So what? In his next four plate appearance, he homers to lead off the third; he doubles, gets balked to third and scores on a sac fly in the fifth; he doubles to lead off the seventh and eventually scores; and he homers again as an eighth-inning coup de grâce. Rickey goes 4-for-4 with a walk and scores four runs. Mets win. Rickey is how old, again? Weeks earlier, as Spring Training got underway, Marty Noble noted in Newsday, “Hard, chiseled, ripped, cut. Choose your adjective. Henderson’s physique is the definition of definition.” Talk about staying in shape. “I still work hard, read pitchers and get good jumps,” Rickey assured the press in December. From the looks of him not to mention his early production, he could have been in the best shape of everybody’s life.

• July 10, the Subway Series at Shea. We remember it as The Matt Franco Game, a 9-8 thriller for our side. Franco singles off the untouchable Mariano Rivera with two out in the ninth. He deserves naming rights. But it’s quietly The Rickey Henderson Game. One of oodles in his career, one imagines. He starts it by singling and scoring in the first. He walks to lead off the third. Singles to lead off the fifth. Doubles with one out in the seventh, well-positioned to trot home on Mike Piazza’s three-run bomb off Ramiro Mendoza, the blast that touched down “halfway up the picnic tent roof,” according to Gary Cohen’s satellite tracking on WFAN (Bob Murphy had asked him, “Where did that land?”). That made it 7-6, Mets. That sent me halfway to the moon way the hell up in Section 36. All day Yankees fans are loudmouths. Mike has shut them up…briefly. The other team’s catcher answers with a two-run homer, and we’re losing, 8-7, going to the ninth. Last year’s most oft-used leadoff hitter Brian McRae is the first batter. McRae grounds out. As if to emphasize what an upgrade was undertaken in December, the lineup turns over and this year’s leadoff hitter Rickey is up. He walks. Soon he’s on third, courtesy of Fonzie’s double. Another out is made. An intentional walk is issued to Piazza. Franco pinch-hits for unknown quantity Melvin Mora. That’s where it becomes The Matt Franco Game, what with the benchman’s “LINE DRIVE base hit into right field!” per Cohen. “Henderson scores! Here comes Alfonzo Here comes Alfonzo…here comes O’Neill’s throw to the plate…Alfonzo slides…he’s safe, the Mets win it! THE METS WIN IT!” And while Matt Franco is being “MOBBED BY HIS TEAMMATES!” it can be quickly calculated that Rickey was on five times in this cauldron of a barnburner, with two walks, three hits and three runs.

• October 4, Cinergy Field, known as Riverfront Stadium to most humans. The game is not on your 1999 pocket schedule because it’s been added after 162 have already been played. The Mets are 96-66. Rickey’s team wanted to win, and they’ve won eight games more than in 1998. Only problem was they worked an epic losing streak into the final two weeks of the season, pulling out of it just in time to make sure they wouldn’t be passed by the surging Reds, who also finish 96-66. The two teams are tied for the one available Wild Card. Rickey leads off the win-or-go-home affair. He singles. I’m thinking roughly the same thing I’m thinking in that Blue Jays-Phillies World Series. Rickey is on base, not good news for the team without Rickey. Fortunately the one I’m rooting for now has him. The next batter, Fonzie, caps off his great year with a two-run homer. Al Leiter will do the rest, by shutting out Cincy on two hits, but he has cushion, thanks to Rickey leading off the fifth with a home run. Rickey was known as history’s greatest leadoff slugger. His tablesetting power exploits weren’t confined to first innings. When the game is over, the Mets are in the playoffs for the first time in eleven years, the fifth time in their history. Rickey enters his seventh postseason.

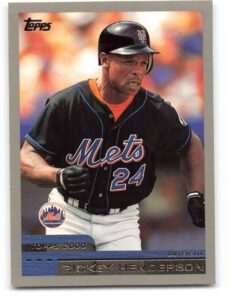

In the first game of the National League Division Series, Rickey goes 0-for-3…while stealing two bases and scoring two runs in the Mets’ 8-4 thumping of Randy Johnson and the Diamondbacks. Rickey was also one of history’s greatest walkers. The Mets couldn’t take Game Two, but Rickey took three more bases — and his sixth of the series in Game Three, a Met romp at Shea (Cedeño also stole one). Decisive Game Four would belong in its nutshell retellings to Todd Pratt, backup to a superstar coming through when it mattered, but let’s not overlook the clutch throw from left field in the eighth inning to nail Jay Bell at the plate. The throw was made by another backup to a superstar, Rickey’s defensive replacement Melvin Mora, rapidly becoming a known quantity amid the melodrama of the Mets’ scramble to keep playing baseball in 1999. Rickey had been aching down the stretch. His batting average took a tumble through September (so had those of most of his teammates), though he finished at .315 in 121 games, complementing his .423 on-base percentage and .466 and slugging percentage, two metrics that didn’t get mentioned a lot at the close of the twentieth century, yet there was Rickey, at forty, putting up numbers in those categories like he did in his early twenties.

When all you can think about is your already pretty good team storming the gates of greatness, you don’t necessarily carve out time to absorb the legends who inhabit your midst. The Mets got Rickey Henderson to make 1999 more successful than 1998? Once in a while, I was capable of stepping back to admire who was suddenly wearing Met snow whites, Met black, occasionally Met pinstripes with too much drop shadowing. Wow, Rickey Henderson is a Met. What became remembered for eternity as the June night Bobby Valentine slipped on dark glasses and a faux mustache to sneak back into the dugout after an ejection during extra innings started with a ride on the 7 with a co-worker I invited along to that game. All this guy, not originally a New Yorker, could talk about was he was going to have a chance to see Rickey Henderson…and the next day, he reiterated how grateful he was he saw Rickey Henderson not just play, but steal a base. This guy wasn’t a Mets fan, so it added a dollop of pride to my hosting him that, yup, we’ve got Rickey Henderson and he steals bases for us.

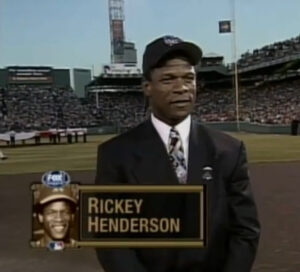

Mostly, though, I wondered over the course of 1999 if Rickey had enough left at his age and within the crankier aspects of his Rickeyness to make a positive difference. Through the long season and the first round of the postseason, he absolutely did. His mentoring of Cedeño when he wasn’t playing provided a second spark to light every game’s fuse. The sight of him sporting a Mets cap when he was introduced among the All-Century 100 at Fenway — he flew up there with Seaver and Kiner — was a reminder of who he’d been and that we were lucky to be getting what he had left. I didn’t initially love that 24 was in circulation after its informal retirement for Willie Mays (Kelvin Torve notwithstanding), but Rickey acknowledged Willie when he put it on and Willie recognized his number being borrowed by somebody whose play was worthy to carry it forward, somebody he called “a good friend”. And when Rickey cringed at his DiamondVision portrayal as a three-eyed Mercury Met, well, you’d cringe, too, if it was revealed to you on an enormous screen that in the future, your forehead could see.

Mostly, though, I wondered over the course of 1999 if Rickey had enough left at his age and within the crankier aspects of his Rickeyness to make a positive difference. Through the long season and the first round of the postseason, he absolutely did. His mentoring of Cedeño when he wasn’t playing provided a second spark to light every game’s fuse. The sight of him sporting a Mets cap when he was introduced among the All-Century 100 at Fenway — he flew up there with Seaver and Kiner — was a reminder of who he’d been and that we were lucky to be getting what he had left. I didn’t initially love that 24 was in circulation after its informal retirement for Willie Mays (Kelvin Torve notwithstanding), but Rickey acknowledged Willie when he put it on and Willie recognized his number being borrowed by somebody whose play was worthy to carry it forward, somebody he called “a good friend”. And when Rickey cringed at his DiamondVision portrayal as a three-eyed Mercury Met, well, you’d cringe, too, if it was revealed to you on an enormous screen that in the future, your forehead could see.

Rickey was no ornament to the 1999 Mets. He was critical to revving their engine. His presence was one among many that come to mind. The year in hindsight inevitably returns a fan to The Best Infield Ever, to Piazza, to Leiter’s two-hitter, The Matt Franco Game, The Todd Pratt Game, the varied exploits from out of nowhere Mora, not to mention the collective blessing-countings we totaled on behalf of having Agbayani and Dunston and Cedeño and Hamilton, not to mention Hershiser and Dotel and Yoshii and Mahomes and Benitez before he became, you know, Benitez. It’s hard to picture your primary leadoff hitter and one of your two future Hall-of-Famers getting a little lost in the big picture one paints in one’s mind for 1999, but Rickey’s not the first Met I think of when I think of that team that I’ve thought about a ton for the past twenty-five years.

Still, I think of him fondly. I willingly overlook, after the fact, that for all the runs he scored — 89, or exactly as many as he did in strike-shortened 1981 when he was 22 — he could intermittently show disinterest in running to first or second or third. When he wasn’t legging out ninety feet following a grounder or was misreading the length of a fly ball he’d just belted, I wasn’t seeing a legend. I was seeing a Met not helping matters. When, in the NLCS, he seemed more concerned with his playing time than whether his team was advancing toward its championship goal, it was a bit of a drag. Rickey saw Rickey being on the field as essential to the Mets winning. Bobby V saw an entire roster and gleaned best options for the situation at hand.

I trusted the manager, even after the clumsy defensive switch of Game Four — Rickey took his position to start the eighth only to have to reverse course in front of 55,000 when Valentine was tardy in tapping Mora to sub for him. There’d be some fuming on the part of the legend that didn’t go unnoticed by teammates. “We’re a scrappy bunch because we don’t quit,” Turk Wendell said afterwards. “Except for one person. You’ll find out who soon enough.” In the Daily News recounting, Turk pointed to Rickey’s unoccupied and empty locker. Rickey, in turn, wasn’t too thrilled with the comments Wendell offered reporters when he made himself available to the media for a response prior to Game Five. “I guess Turk doesn’t know me if he thinks I’m a quitter” was the gentlest retort. More pointed, per the News: “If he’s got something to say about it, tell him to meet me. I’ll beat his ass.” The episode couldn’t help but strike a sour note in the jubilant clubhouse on the heels of the Mets avoiding getting swept (thanks in no small part to Mora’s role in the winning rally in the bottom of the eighth). Whether they were issued in the pursuit of peacekeeping or out of sincerity, Valentine and Wendell crafted apologies, and no asses were beaten.

On the other hand, I wasn’t deeply disturbed that Rickey was “caught” playing cards with Bobby Bonilla in the midst of the sixth game of the NLCS at Turner Field, a nugget that dribbled out a little later. They had each played, they had each been removed. Rickey doubled behind Matt Franco in the seventh, when John Smoltz, who’d started three nights earlier, was brought in to put the pennant in a stranglehold for Atlanta. It was 7-3, Braves. Rickey’s RBI made it 7-4. Rickey’s ensuing run — moving to third on Fonzie’s flyout, coming home on Oly’s single — made it 7-5. Then Mike batted and it was 7-7, and after being down, 5-0, we were tied. This was after the Grand Slam Single in Game Five and the Mets getting to Rocker in Game Four, and tell me we weren’t going to win Game Six, then Reed wasn’t going to best Gl@v!ne in Game Seven.

Mora’s pinch-RBI single in the eighth, delivered while batting for Hershiser (our fifth reliever of the night), meant Melvin was already in the game. We led, 8-7, going to the bottom of the inning. We needed a new pitcher. It was John Franco. Franco had to be inserted into the batting order, somewhere harmless. Defense was vital with a one-run lead. Melvin had been making plays all postseason. He’d registered an assist apiece from left, center and right, each of them cutting down an out at the plate. Bobby wanted him in right, where Agbayani had been camped. Agbayani had led off the Met eighth with a single. It was Benny who scored the go-ahead run. Bobby shifted him to left.

Future Hall of Famer Rickey Henderson was out of the game. Except for the game of hearts or whatever it was he and Bonilla engaged in so Rickey could blow off steam. Per Bonilla many years later, “Rickey says to me, ‘Bo, get the deck of cards, let me relax my mind.’ And the reason we did that, we actually had played cards al year long. This was more to relax Rickey. We had the game on, we’re playing cards.”

That was Bonilla’s recollection in 2017. In 2000, Henderson told Bob Klapisch, then with ESPN, “We were in the clubhouse, that’s true, but that’s because me and Bobby were already out of the game. But there were five pitchers in there with us. How come it was OK for them to be in there, but not us? Why do people only talk about me and Bobby? We played cards before the game, but that’s the same thing we did all year. There was no [card] game going on at the end. We were watching the game.” Yet another Met in the aftermath of the loss to Atlanta recalled seeing their teammates invested in their own game rather than the one that went awry on the field: “We wanted to take a bat to their heads.”

Better optics would have had every Met on the bench as the Mets fought to hold on to their slim lead. Better tactics, perhaps, would have had the eventual all-time leader in walks (until Barry Bonds, who was intentionally passed to extremes, passed Rickey), steals and runs, not to mention collector of 3,000+ hits, in the dugout suggesting something he saw in some Brave’s approach that might provide the needed inch in a series, never mind game, of inches. Better understanding of the human psyche would explain why one of the best baseball players ever felt it was better to stay away from a live, in-person look at one of the best baseball games anybody would ever see.

But Rickey had been removed from that game, and the game continued without him. In another postseason, another player for the ages, Keith Hernandez, repaired to his manager’s office, while what was about to become a game for the ages was still in progress. Found a chair, found a beer, decided his actions were bringing good luck to the proceedings that were progressing in his absence. Superstition sometimes supersedes optics. Still, if you think about it, Keith gave up when there were two outs and nobody on, down two. Gary Carter, Kevin Mitchell, Ray Knight and Mookie Wilson hung in there. Mets won that Game Six, 6-5.

No such fortune for the 1999 Mets, who allowed the Braves to tie their Game Six at 8-8 in the eighth, before the combatants exchanged runs to make it 9-9 in the tenth and the Mets gave up the ultimate fall-behind run in the eleventh to end their pennant quest, 10-9. Had something more gone right, or something less gone wrong, “the deck of cards” would have rated display in the Mets Museum.

Rickey came back for a second season with the Mets. Derek Bell, new to the team, referred to Rickey as “the greatest teammate I ever had. I learned more about basestealing in 30 minutes from Rickey in Spring training than I did in my whole career. The guy is unbelievable, what he knows, what he sees in a pitcher.” Nonetheless, Rickey didn’t last past the middle of May 2000. One Friday night, Rickey was certain he’d hit a homer and went into his trot. The ball did not leave the park — it hit the base of the left field wall — and Rickey did not run beyond first. By eschewing a sure double, Rickey had written his ticket out of town, getting himself released after the next day’s game, though not before an interlude that, if you remember the Bobby Valentine era with any clarity, could have happened only at Shea.

On Friday May 12, he hits what amounts to the inverse of the Grand Slam Single (a ball that doesn’t go out, but the batter is sure it did). Hell breaks loose in the papers. The manager: “I told him it’s not acceptable. Hit one 400 feet before you pull that crap.” The player: “I hit a ball like that, I think the ball’s going out of the ballpark. What do want me to do, sprint again?” and, better yet, “I’m gonna do it again if I hit one like that.”

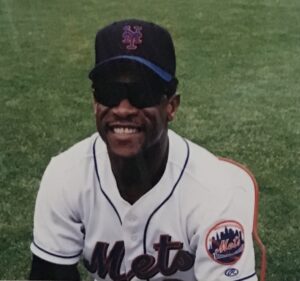

Legend or not, that was that. The release came after the Mets lost to the Marlins on Saturday May 13. Steve Phillips summed the Rickey Henderson experience at its end: “At some point, it becomes too much.” But it’s significant to note the Mets held on to Henderson for that game in between the incident and the release. The morning of the May 13 game happened to be Photo Day at Shea, in which the first 5,000 fans with a ticket, a camera and a cash register receipt from sponsor Genovese Drug Stores got to line the warning track and take pictures of Mets players, conveniently spaced around the outfield for shutterbuggers’ pleasure. This was before people carried phones that could capture images with minimal fuss. This was a big promotion.

Legend or not, that was that. The release came after the Mets lost to the Marlins on Saturday May 13. Steve Phillips summed the Rickey Henderson experience at its end: “At some point, it becomes too much.” But it’s significant to note the Mets held on to Henderson for that game in between the incident and the release. The morning of the May 13 game happened to be Photo Day at Shea, in which the first 5,000 fans with a ticket, a camera and a cash register receipt from sponsor Genovese Drug Stores got to line the warning track and take pictures of Mets players, conveniently spaced around the outfield for shutterbuggers’ pleasure. This was before people carried phones that could capture images with minimal fuss. This was a big promotion.

I didn’t partake, but my friend Joe did. Not only did Joe get up early and haul his camera for the event (I’d meet him in the afternoon for the actual game), he’d thoughtfully surprise me months later with an album recording his experiences from that morning, filling it with copies of his snapshots and a typed description of each encounter, from Dennis Cook (“polite, but never left his chair”) to Jon Nunnally (“like a kid in a candy store, full of smiles and accepting well wishes from the fans”) to Mike Piazza (“I had to stand over people to get this candid portrait of him. Then again, no photo of Mike Piazza could ever be a bad one.”). Joe greeted Benny Agbayani with an “aloha,” inspired Rick Reed to dash to the outfield (by recalling the night Reeder played one inning in right) and bonded slightly with Robin Ventura over the stylish 1980s White Sox logo on Joe’s jacket. There is no picture of Todd Pratt, because by the time Joe reached Tank’s station, “I simply ran out of film,” something a person practicing photography in 2000 was prone to do.

I’d forgotten about most of Joe’s encounters, but when I learned about Rickey Henderson’s Friday night passing this past Saturday (December 21, the day of the year with the least sunlight), I immediately thought of that album and Rickey’s inclusion in it. I dug it out to reread what Joe wrote:

Photo Day turned out to be Henderson’s swan song with the Amazins after a turbulent year-and-a-quarter. He, along with Mike Piazza, received the most fans. Surprisingly, Rickey’s visitors were kind and supportive. One woman told him, “Pay no mind to what those reporters say. You just keep doing what you’re doing.” I shook his hand and offered a few seconds of encouragement. He, in turn, smiled for my lens.

Sure enough, there’s Rickey, smiling as a Met, which harmonizes with so much I’ve read and heard since he died a few days short of his 66th birthday. Rickey’s smile has been a common theme in the remembrances from teammates, fans, everybody. And he definitely had a career to smile about. It would keep going despite the unpleasant conclusion of his New York affairs. Seattle picked him up and, lo and behold, Rickey’s helping yet another team the playoffs in 2000, part of the same postseason the Mets made despite having to sort through a dozen leadoff hitters now that they’d said goodbye to Rickey and, for that matter, Cedeño, the young speedster they traded to Houston with Octavio Dotel to bring over Mike Hampton and Derek Bell (Roger never again stole as many as he had under Rickey’s guidance). Late in the year, Bobby V decided on Timo Perez, a sparkplug down the stretch and in the first two rounds of October. Then, in Game One of the World Series, Timo the leadoff hitter, from his vantage point of first base, watches a ball sail to deep left field. Like Rickey in May, he assumes it’s going out. Like Rickey, he is mistaken. The consequences prove dire at home plate. It should also be noted that the Met who hit that ball, Todd Zeile, didn’t exactly bust it out of the box, either. After a generation in which he influenced the game, everybody in baseball seemed to have now and then taken a cue from Rickey Henderson.

While he could still play, Rickey played. Rickey at 42 returned to the Padres for a year, then the Red Sox at 43, then the Dodgers at 44, making it nine franchises in all. Rickey plays his last major league game in 2003, slating him for Cooperstown come 2009. In between, before he briefly served as first base and baserunning coach for the Mets in 2007, he’s in the independent leagues for a couple of seasons. The year this blog started, 2005, he was a San Diego Surf Dawg. The year he started playing professionally was 1976, the year I was bar mitzvahed. Calling him a four-decade player almost undersells his longevity.

Since time in the unaffiliated minors doesn’t interfere with a player’s Hall of Fame eligibility once he’s done with the majors (or the majors are done with him), 2009 indeed became the year Rickey Henderson was certified immortal. Six month before delivering his speech upstate, he appeared on The Late Show with David Letterman along with fellow electee Jim Rice to deliver Top Ten Highlights of My Hall of Fame Baseball Career. Number Five was Rickey’s line:

“Being a Met, a Blue Jay, a Padre, a Dodger…hell, even I cannot remember all the teams I played for.”

That was probably true. When Rickey did speak at Cooperstown, it was all very gracious. I don’t remember him mentioning the Mets. I didn’t take it personally. He had a lot to remember, just as he gave everybody who cherishes baseball a treasure trove of memories. Especially in the place where they named the field for him. “Rickey Henderson Field” at Your Name Here Coliseum was a rare tone-conscious touch for the Athletics in the years ownership began steering the local club out of town. The man himself remained deeply linked to the city of Oakland, where he grew up, despite departing it on numerous occasions for business reasons. Oakland having to say goodbye to Rickey this December after watching the A’s pick up stakes in September brings to mind the sorrow of Brooklyn Dodgers fans in the winter following 1957 when their team flew west to stay and their catcher Roy Campanella suffered a paralyzing automobile accident. The bittersweetness lingered over the borough a long time. Maybe it still does. Nevertheless, they’d had the Dodgers and they’d had Campy behind the plate and the Boys of Summer populating Ebbets Field. As the years went by, Brooklyn Dodgers fans had to smile for how it had been.

Me, I wouldn’t have remembered much in the way of the Rickey smile from his turbulent tenure among us, but I’ve got Joe’s photography to correct my perception. And I maintain the good vibes, whatever hard feelings existed in given moments, of knowing Rickey Henderson was a New York Met. Among his many Hall of Fame qualities that have been remarked upon these last few days — as the baseball-loving world absorbs the loss of yet one more indelible character in the year we’ve said goodbye to Willie Mays, Orlando Cepeda, Luis Tiant, Pete Rose, Rocky Colavito and Fernando Valenzuela (not to mention five 1969 Mets, most recently Jack DiLauro) — was Rickey’s generosity. One of the most heartwarming stories to have been told and shared this week is from Mike Piazza’s memoir, in which the superstar catcher recalled Rickey not getting with the program when it came to doling out postseason shares to short-time players and non-playing team employees who are easy enough for millionaires to miss. Usually, the guys who come and go in the course of a successful season are voted not nearly as much as the roster mainstays.

“Whenever the discussion came around to what we should give one of the fringe people — whether it was a minor leaguer who came up for a few days or the parking lot attendant — Rickey would shout out, ‘Full share!’ We’d argue for a while, and he’d say, ‘Fuck that! You can change somebody’s life!’”

Spoken like somebody who changed the game every time he stood on first and decided he’d rather be on second.

Great job as usual, Greg.

Funny thing about these superstars.

They should show some respect and not even ask for NUMBER 24.

At least Torve didn’t abandon his teammates to play cards during the game.

And did we really give 24 to Cano, that lazy, steroid-taking bum?

What miscreant are we going to give 41 to next?

Well we did give it to the ballpark a couple of years back…

When I started reading this article, I said, “This can’t be an obit. I mean, we’re talking Rickey Henderson. He’s way too young!”

No question, Rickey was a presence throughout his career, and well deserved his HOF first-ballot induction. I wasn’t such a huge fan of his Met tenure – that card game with Bobby Bo is what I tend to remember – but there’s no denying the impact he had on the way the game was played. RIP.

By the way – Fernando’s gone? Oh man. Not a Met, but every Latino pitcher we’ve had since his time owes him a debt of gratitude. Also way too young.