Spring Training, you gotta stop making real news. Frankie Montas’s lat last week [1]. Nick Madrigal’s shoulder over the weekend. Sean Manaea’s oblique [2] as the Monday surprise du jour. We’re here for bright skies and optimism and megastars presenting vehicles to would-be stars in exchange for jersey numbers. That’s the news we can consume and smile about.

All injuries come at the wrong time. All injuries are unfortunate. Some come at a worse time than others. Some are more unfortunate than others. Aesthetically, Spring is a bad time for injuries. As a practical matter, the earlier an injury occurs, the longer there is the opportunity for recovery or, if necessary, replacement. If you lose for a while a player who rates as replaceable…well, let’s not treat human beings as commodities if we can help ourselves. Still, as Anthony DiComo pointed out, the Mets have 68 guys in camp [3]; plus there are a couple of familiar fellows out there who are still unengaged by any organization; and we just picked up an outfielder named Alexander Canario [4] from the Cubs, which, I suppose means we have 69 guys in camp. Nobody’s a commodity, but it’s nice to have alternatives.

Montas goes down for a while? Good thing we have pitching depth. Manaea goes down, likely for less while, but still a while? The depth isn’t as deep, and Manaea is inarguably most vital to the Mets’ pitching plans. Clay Holmes looked good Saturday, Max Kranick pretty solid on Sunday. People step up. People earn closer looks. We’re better off with Manaea’s oblique clearing up. But somebody’s gonna have to pitch in his stead for a spell. No wonder reports of Jose Quintana withdrawing from Colombia’s WBC qualifier team raised multiple antennae Monday night.

Madrigal we barely know except that he was brought in as an infield backup instead of Jose Iglesias. Something about options and flexibility. Now Madrigal’s out “for a long time [5]” with a fracture, per Carlos Mendoza, and you’re left to wonder when Iglesias stopped being an excellent defender and reliable hitter. Then you remember, oh right, options and flexibility. Youth as well. I, too, would like to see more Luisangel Acuña. Not sure bench guy is his ideal role from jump in 2025. Or maybe sitting behind major leaguers in April beats starting every day in Syracuse.

Here I am, immersed in actual Met news and its impact before March. No, that’s not what you want a lot of in Spring. You want stories about numbers on the backs of jerseys and what it takes to shift them to the backs of other jerseys.

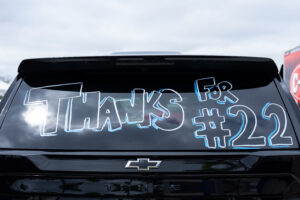

Saturday, Juan Soto homered the first time ever [6] we saw him swing as a Met, a cause for instant celebration for those of us tuning in from anywhere for a taste of Spring. Further down the lineup in that very same inning, we could be pretty happy that Brett Baty beat out an infield grounder by motoring to first base. Of course he motored. Brett Baty has a sweet new ride [7], a situation directly related to Juan Soto not having to get confused when he dresses. Win-Win!

Soto, who’s worn 22 at every major league stop before arriving at what we hope is his last and most glorious, came to a team where that number was assigned to a former first-round draft choice whose development has stalled like he trusts his sweet new ride won’t. Baty’s worn 22 since he was 22 and hinting that he’d be the Mets’ third baseman for the foreseeable future. That was in ’22. Times, it is said, change. Numbers, it should also be said, players need to be malleable about.

Before Christmas of 2024, there was Soto trying on 22 at Citi Field, as clearly his as it was Donn Clendenon’s and Ray Knight’s while they were proving themselves Most Valuable in the cause of the Mets winning World Series. Donn hit .357 with three homers in 1969. Ray hit .391 with an enormous Game Seven dinger in 1986. Clendenon and Knight earning their respective WS MVP honors wearing the number that they did has given 22 a little extra historical oomph in Met annals. It also belonged to as valuable a performer as the Mets had in another Fall Classic, Al Leiter: two starts, one hard-luck no-decision in Game One, one heartbreaking defeat in Game Five, a combined 268 pitches’ worth of blood, sweat and tears trickling across two boroughs’ mounds in his wake. Things go a little better in 2000, we probably have three 22s getting presented an October MVP.

For the record, Juan hit .333 with three homers in a World Series his team won, and .313 with another longball in a World Series his team lost. Think hard before betting against 22 when fall comes to Flushing.

The same digits Clendenon, Knight, Leiter and Soto have made memorable also made a habit of gracing the backs of players who engendered high hopes unmet somewhere between various Aprils and Septembers. Witness mid-’90s five-tooler Alex Ochoa; future closer of the 2000s Royce Ring; 2013 top pick Dom Smith. Ochoa cycled through a few moments in 22 before getting shipped to Minnesota for Rich Becker. Ring as 22 notched no saves for us, or anybody else in any number. Smith, in 22 between 2017 and 2019, produced [8] some big hits before dropping a 2 in deference to former Cy Young Award winner Rick Porcello. Got a few more [9] wearing just 2 until fading from our scene in 2022. Dom put a lot together [10] as a Met, but fell a little shy of putting it all together.

Like any number, 22’s success rate has depended on who’s been wearing it when. Few Mets could be more rewarding to watch than No. 22, Kevin McReynolds, at his 1988 peak. Few could be more disappointing to watch than No. 22, Kevin McReynolds, as he descended from that peak. We experienced Porcello long past his Cy status, in 22 in what there was of 2020; Willie Harris after he was done robbing us with regularity, in 22 for the duration of 2011; Ender Inciarte after he was done robbing us with regularity, in 22 for two pre-Baty weeks in 2022; and Brett Butler, four years after signing him as our leadoff hitter would have been a capital idea, in 22 for not quite four months in 1995. Jose Valentin was awesome all year in 18 in 2006, less so after switching to 22 in 2007, a year he got injured in July and never played again.

Conversely, Jack Fisher was sturdy as hell for 133 starts over four seasons in 22. Eric Young, Jr., swiped a stolen bases crown in 22. Mike Jorgensen did defensive wonders at first base and once won a game on a walkoff grand slam in 22. If forces hadn’t conspired to send Duaner Sanchez out for a late-night cab ride in Miami, I’m convinced Xavier Nady would have worn 22 in the 2006 World Series. Instead, he was traded to Pittsburgh because we needed Roberto Hernandez to reinforce the bullpen in Sanchez’s absence. The next time we were in the World Series, the Met in 22 was Kevin Plawecki, who caught only ceremonial pitches through three rounds of postseason inaction in 2015, suggesting that betting on 22 when fall comes to Flushing can be a bit of a crapshoot.

All those ups and downs for 22, from Bob Moorhead in 1962 to Brett Baty in 2024, but Soto had to have it. Juan wasn’t signing a record-breaking deal with the Mets to feel the slightest bit uncomfortable. Fortunately, Baty, whose grip on his number grew more tenuous than his grip on his roster spot, wasn’t going to be made to feel discomfort, either. Should Brett actually be a Met in the season ahead (third base is otherwise occupied), he will do it as No. 7, a selfless selection Brett said he went for in deference to his youthful affinity for one Met legend and one Hall of Famer.

Had things worked out perfectly, those would both identify Jose Reyes, but the Hall of Famer in Baty’s esteem is Joe Mauer. Before Baty’s switch, good ol’ 7 was out of circulation in these parts for several seasons. Marcus Stroman last wore it for the Mets, in 2019, then said it didn’t seem proper because it truly belonged in Queens to his former Blue Jay teammate Reyes — by then no longer playing — and switched to 0. With numbers being retired with surprising frequency in recent years, I wondered if 7 was being set aside for its own day of honor, whether for Jose, or our all-time avatar of tenure Eddie Kranepool, or the two of them in tandem Berra-Dickey style. Now it’s back on the field, and, honestly, it looks good on Brett.

[11]Even better-looking from Baty’s perspective is what resides in his parking space: a spanking new Chevy Tahoe, courtesy of the newest 22 in camp. The SUV is Soto’s “thanks, dude” to Baty for being so accommodating with his digits. Brett has until now been driving what he considers a hardy old Toyota, specifically a 4Runner. It’s a 2016. I drive an old Toyota that’s proven plenty hardy, despite it being smaller than Brett’s vehicle and considerably older than Brett himself. I’d say we Toyota guys have to stick together, but there’s the kid moving into his new model. Good for Baty. Good for Soto. Good for us. As baseball fans, we are primed to love numbers and cherish camaraderie. Whatever makes our guys happy and brings them together and revs them toward a winning season, right?

[11]Even better-looking from Baty’s perspective is what resides in his parking space: a spanking new Chevy Tahoe, courtesy of the newest 22 in camp. The SUV is Soto’s “thanks, dude” to Baty for being so accommodating with his digits. Brett has until now been driving what he considers a hardy old Toyota, specifically a 4Runner. It’s a 2016. I drive an old Toyota that’s proven plenty hardy, despite it being smaller than Brett’s vehicle and considerably older than Brett himself. I’d say we Toyota guys have to stick together, but there’s the kid moving into his new model. Good for Baty. Good for Soto. Good for us. As baseball fans, we are primed to love numbers and cherish camaraderie. Whatever makes our guys happy and brings them together and revs them toward a winning season, right?

Wright.

David Wright just pulled into the alumni parking lot of my mind, because the last time I gave uniform numbers much thought was last month when David was humbly conducting his media Zoom call regarding the forthcoming retirement of 5, a number beyond even the compensatory powers of Juan Soto. Naturally David did his press availability humbly. It’s how he’s forever done everything.

Had David been left to retire 5, he would have done it for Ed Charles or Davey Johnson or John Olerud or Chico Escuela. There are barrels of fun 5s in Mets history [12]. David might not know of everybody to have worn it before him, but to listen to him reflecting on his career, he’d believe anybody would deserve the highest honor a franchise could bestow before he should receive it.

“I don’t think it’s hit me,” he said on the cold afternoon of January 8. “I don’t think it’s ever gonna hit me. I truly feel like it’s a bit undeserved, given the skill and accomplishments of some of the numbers I’ll be amongst up there. I joke that I think there should be a special section for my number because it’s probably not deserving of being amongst the really, really good players in the organization.”

In Wright’s world of accomplishment, he somehow fancies himself Wayne and/or Garth. “I’m not worthy! I’m not worthy!” You can’t read a list of Met career totals in just about any offensive category and not run into WRIGHT right away. But that’s the same David who stood in front of his locker after wins uninterested in burnishing his base hits or runs batted in because all that mattered was the team won, the same David who took losses upon himself, never mind that baseball is a team game and too often his team was stocked with players not on his level.

[13]Now his level will be up there “amongst” Seaver and Strawberry and the rest of the Metropolitan immortals. I could name them all, but reciting Met numerical retirees now takes a minute. Live long enough, huh? I lived too long with the Mets ignoring their past to not adore them embracing it. It’s how we show our respect, and I have affection for the acknowledgment. Whether they rediscovered 36, remembered 24 or took care of the teens, 5 was a gimme from the time it was hung up by The Captain in 2018. As of July 19, David Wright, age 42, will be the youngest Met to have his number retired. He still had to wait too long.

[13]Now his level will be up there “amongst” Seaver and Strawberry and the rest of the Metropolitan immortals. I could name them all, but reciting Met numerical retirees now takes a minute. Live long enough, huh? I lived too long with the Mets ignoring their past to not adore them embracing it. It’s how we show our respect, and I have affection for the acknowledgment. Whether they rediscovered 36, remembered 24 or took care of the teens, 5 was a gimme from the time it was hung up by The Captain in 2018. As of July 19, David Wright, age 42, will be the youngest Met to have his number retired. He still had to wait too long.

It was five accompli, wasn’t it? They never gave out Wright’s number, just like they never gave out Stengel’s, Hodges’s, Seaver’s or Piazza’s once they were done (whereas 36 was issued to 27 different Met players plus Mickey Callaway in the four decades following Jerry Koosman’s departure from Shea). We didn’t have to dwell on it too long while it wasn’t happening or stew about its worthiness once it did happen. This was pretty close to old school number-retirement, fitting for an old-school player.

Another fitting juxtaposition from my early-January perspective was that Wright was directed to sit and be reminded by reporters of how marvelous a career he’d conducted one day before the nation had the privilege of being reminded what a person we once elected president.

In baseball, when appropriate, we retire a number. In America, when a prominent individual’s time arrives, we conduct a state funeral. It’s how we show our respect and, unless we’re made of stone, express our affection. Circumstances presented an intersection of aspects of both rituals in deepest winter. They each got my attention. A day after David of Virginia delivered his eternally sincere aw-shucks self-appraisal, national remembrance for President Jimmy Carter concluded. One Southern gentleman given his flowers in his forties, another passing at a triple-digits age and being remembered warmly in the aftermath of a remarkable life.

Both men always exuded graciousness in their time in the spotlight. Carter wasn’t as humble as Wright, but who is? Also, Jimmy Carter rooted for the Atlanta Braves, which may have been the only policy position of his I viewed as beyond the pale. He came by it honestly, however, being from Georgia and all. The man could count Henry Aaron as a friend. Pretty classy company when those two Peach State icons got together.

[14]No doubt somebody who shows up to applaud Wright in July will have grumbled way back when that he couldn’t lift a simple fly ball with a man on third and nobody out. The strikeouts and popups of yore are easily obscured in a toast to the long run. Politics can be a tougher sell for the act of forgiving and forgetting, which is what makes a state funeral such an stupendous occasion. People who had no more than modest use for you in life say nice things about you. People who are on record as saying terrible things about each other come together in comity. It’s like we’ve all grabbed a stool at Cheers and George Wendt has walked in. Norms! They can come off as a tad hypocritical if you have a memory. They can also come off as a civil and comforting.

[14]No doubt somebody who shows up to applaud Wright in July will have grumbled way back when that he couldn’t lift a simple fly ball with a man on third and nobody out. The strikeouts and popups of yore are easily obscured in a toast to the long run. Politics can be a tougher sell for the act of forgiving and forgetting, which is what makes a state funeral such an stupendous occasion. People who had no more than modest use for you in life say nice things about you. People who are on record as saying terrible things about each other come together in comity. It’s like we’ve all grabbed a stool at Cheers and George Wendt has walked in. Norms! They can come off as a tad hypocritical if you have a memory. They can also come off as a civil and comforting.

Our 39th president died on December 29. Ceremonies at different sites commenced within a week and continued through January 9. Seems like ages ago this happened in Washington. It was only last month. The goodbye was long, as was the nation’s preparation, given that Carter was announced as going into hospice care nearly two years before. The life was incredibly long in every sense. Jimmy lived to be 100, long for anybody, record-breaking for a president. The post-presidency beat everybody else’s, too. It went on for nearly 44 years and it was packed full of initiative and accomplishment. We should all make the most of our second, third and however many acts we get.

In the same way David Wright’s career pushed temporal boundaries [15] for a Met, Jimmy Carter’s stay in the public consciousness outdid just about everybody’s as a going concern. Among the several touching eulogies delivered at the National Cathedral were a pair prepared by men who preceded President Carter in death. When the next generation is sent in to read the words of their fathers, that says something about how long the deceased hung in there.

Steven Ford, for his late father, President Gerald Ford:

“Inspired by his faith, he pursued brotherhood across boundaries of nationhood, across boundaries of tradition, across boundaries of caste, in America’s urban neighborhoods and in rural villages around the world. He reminded us that Christ had been a carpenter. And in Third World villages, he successfully campaigned, not for votes but for the eradication of diseases of diseases that shame the developed world as they ravage the undeveloped one.”

Ted Mondale, for his late father, Vice President Walter Mondale:

“Towards the end of our time in the White House, the president and I were talking about how we might describe what we tried to accomplish in office. We came up with a sentence which remains an important summary of our work. We told the truth, we obeyed the law, and we kept the peace. That we did, Mr. President. I will always be proud and grateful to have had the chance to work with you towards noble ends.”

Other eulogists were able to speak eloquently for themselves. There was plenty nice to say from the pulpit. There was plenty nice to feel from afar. Scheduled with little notice but planned to a tee, every state funeral for a president, even the presidents I wasn’t necessarily crazy about, I allow myself a generosity of spirit [16] while they’re in progress. It’s a moment to be an American rather than a partisan. Nixon was a complex thinker; Reagan radiated sunniness when the cameras rolled; Ford was a tonic for our collective soul [17] when we needed it; the first Bush really adored his grandchildren and threw out a couple of first pitches at Shea.

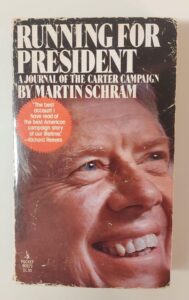

[18]Carter I actually was crazy about, handing out campaign literature on his behalf on Election Day 1976. I have a poster from that fall somewhere in a closet along with a couple of campaign buttons. He wasn’t my first choice in ’76 — I was a Scoop Jackson kid, initially — but I could see why his bandwagon rolled and I was happy to jump on board in summer. As his tenure in the White House wore on, I maintained my loyalty to and confidence in him to the end, sort of like I did for someone else whose reviews turned mixed after taking office in 1977: Met manager Joe Torre. The only thing I was running as they took on what I perceived as the two most important jobs in the world was a high school newspaper. I think I looked up to each of the commonalities implicit in their leadership styles, which seemed to amount to, “I know you’ve got problems with the results right now, but trust me, I know what I’m doing here.” Neither stayed in his role past 1981, the year I graduated from managing the Tide.

[18]Carter I actually was crazy about, handing out campaign literature on his behalf on Election Day 1976. I have a poster from that fall somewhere in a closet along with a couple of campaign buttons. He wasn’t my first choice in ’76 — I was a Scoop Jackson kid, initially — but I could see why his bandwagon rolled and I was happy to jump on board in summer. As his tenure in the White House wore on, I maintained my loyalty to and confidence in him to the end, sort of like I did for someone else whose reviews turned mixed after taking office in 1977: Met manager Joe Torre. The only thing I was running as they took on what I perceived as the two most important jobs in the world was a high school newspaper. I think I looked up to each of the commonalities implicit in their leadership styles, which seemed to amount to, “I know you’ve got problems with the results right now, but trust me, I know what I’m doing here.” Neither stayed in his role past 1981, the year I graduated from managing the Tide.

They each generated far better press for themselves in the decades that followed. Former President Carter won the Nobel Peace Prize and global admiration. Torre’s in the Hall of Fame for non-Met reasons, though it says NEW YORK N.L. somewhere on his plaque if you look closely.

Keep an eye on those next acts. The Mets will begin theirs before March ends. In the meantime, enjoy Spring and hope its remaining news rarely exceeds the trivial.