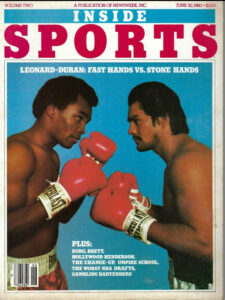

Before he incurred infamy for the two words he uttered to communicate he wanted no more of his 1980 rematch versus Sugar Ray Leonard — “no más” — Robert Duran was mainly recognized as the fighter who was “pound for pound” the best in the world. Duran is the reason I learned that phrase. For years, it was all I knew about the man. He won titles in four different weight classes, none of them heavyweight. Heavyweights were who on TV when I was growing up, so I knew about Ali and Frazier and Foreman and Holmes and Norton and Spinks. I didn’t really know about anybody trimmer. Ah, the boxing writers would tell me through their columns, there is a fighter who outshines them all, “pound for pound”. You couldn’t expect Duran to get into the ring against those much bigger men, but when you took into consideration everything about who could do what within the confines of the squared circle and the sweet science, pound for pound, he was the best.

[1]I’ve got a Mets season that answers the bell to such a description. For most of 162 games, it punched far above its weight class. When it inevitably went down for the count, I wasn’t ready to throw in its towel. Más, por favor. Mucho más.

[1]I’ve got a Mets season that answers the bell to such a description. For most of 162 games, it punched far above its weight class. When it inevitably went down for the count, I wasn’t ready to throw in its towel. Más, por favor. Mucho más.

Pound for pound, no Mets season has ever made me happier.

4. 1997

I’ll always remember what somebody with whom I’d someday write a blog e-mailed me during a Spring when little good was forecast for the shared object of our affections. I wasn’t particularly optimistic. My friend made me look like the hopeful one.

“Bobby Valentine’s a terrible manager,” he assessed. “The Mets are gonna lose a hundred games.”

When I brought his words up to him months later, his prediction no longer mathematically viable, he responded that there may be nothing better than being proven wrong about how bad your baseball team is going to be.

That was a page Jason and I were both on long before we grabbed this here URL.

Nobody saw them coming. I doubt many remember them staying. But there they were, for as long as they existed as an active entity, progenitors of perhaps the most satisfying, least gaudy season in Mets history. That’s a subjective call. But I’m the one making the call on this subject, as I have been throughout MY FAVORITE SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-‘PRESENT’ (with 2024’s slotting TBD) [2]. The only aspect of the season turned in by the 1997 Mets that didn’t satisfy me, for a while, was how obscure it became shortly after its conclusion. That bothers me less now.

I didn’t intend it to be, but 1997 seems to be my little secret. An open secret, available to the Mets-loving world at large, but one destined to move along quietly in the historical shadows. The larger Metropolitan narrative pretends Mike Piazza smote the ground the second he stepped off his plane at LaGuardia on May 23, 1998, and out sprang a Mets club fully grown and ready to accomplish audacious things. Getting Piazza was huge. What happened after Piazza was gotten was huge. But something beautiful was blossoming a year prior to Piazza, before many were paying attention — regardless that there was much of a captivating nature already in progress.

It was the same year the Will Smith/Bernard Gilkey vehicle Men In Black was in theaters. Erasing memories must have been all the rage.

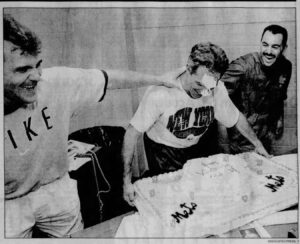

[3]Though I’m not a big fan of the word “forgettable,” I wouldn’t have anticipated 1997 becoming a memorable Met season. Maybe because of the months that followed, I’ve never forgotten the first tableau to make an impression on me that year, during Spring Training. Pitchers & Catchers were reporting on February 14. The senior pitcher and senior catcher in terms of Met service, John Franco and Todd Hundley, thought it appropriate to welcome their manager to Port St. Lucie with a cake bearing his name. The gesture appeared a little suspicious despite it being Valentine’s Day. Valentine’s Day usually involves candy rather than cake.

[3]Though I’m not a big fan of the word “forgettable,” I wouldn’t have anticipated 1997 becoming a memorable Met season. Maybe because of the months that followed, I’ve never forgotten the first tableau to make an impression on me that year, during Spring Training. Pitchers & Catchers were reporting on February 14. The senior pitcher and senior catcher in terms of Met service, John Franco and Todd Hundley, thought it appropriate to welcome their manager to Port St. Lucie with a cake bearing his name. The gesture appeared a little suspicious despite it being Valentine’s Day. Valentine’s Day usually involves candy rather than cake.

But you can’t smush an unsuspecting recipient’s face into a box of chocolates. That was the clubhouse gag. John and Todd, the only players extant who could remember what it was like to play on a Mets team with a winning record, way back in 1990, lured Bobby Valentine into their frosted trap, and next thing he knew, the skipper was wiping icing from his forehead and chin.

Bobby V, as he was universally called, became the manager the August before, as the latest losing campaign led by Dallas Green wound down. To be fair to Green, he wasn’t doing markedly worse with the Mets than his several predecessors had. The last time Spring Training served as prelude to a statistically successful Met season, Davey Johnson was ensconced in the manager’s office. By 1997, Davey’s 1984-1990 Met tenure seemed ages ago. Its only relevance in the present was when it began, it included Bobby Valentine as third base coach.

Bobby was part of Davey’s staff before he getting the opportunity to manage in Texas. He took over the slumbering Rangers in 1985, roused them to authentic contention in 1986, but never boosted them to the playoffs. The team owner and President George Bush’s eldest son, also named George Bush, let him go in ’92. Valentine managed Triple-A Norfolk for one year, left for Japan to lead the Chiba Lotte Marines for one year, and then returned to the Tides. He was a phone call away in case the Mets decided they’d had enough of Green, a fate waiting to befall every manager. On August 26, 1996, with the Mets floundering at 59-72, Dallas was thanked for his service.

We’d been through Buddy Harrelson, Mike Cubbage and Jeff Torborg before Dallas’s once-welcome tough-guy act wore out. Bobby, the clever Connecticut native who played for Joe Torre’s Mets, had been angling for another MLB shot ever since his Arlington goodwill expired. “The most unfair criticism is I never won,” Bobby said when he took the helm in late summer. “At the same time it’s the most factual.” My friend Jason’s idea that Valentine might not be the answer for 1997 wasn’t exactly iconoclastic. Bobby V’s dugout decorum was disdained in ingrained baseball circles as that of a “top step” character, a little too ostentatiously into the game, a little too convinced he’d invented it. “So often accused of being a major league know-it-all” is how Marty Noble reintroduced the Mets manager to his Newsday readers in February.

The end of ’96, when he oversaw a 12-19 conclusion to the ongoing doldrums, gave him a glimpse of a club he knew required reshaping. He came into his first camp as Met manager preaching preparation and awareness, likely determined to come off as less of a hardass than his predecessor. Franco and Hundley did all right under Green. Preparation? “I know what I have to do to get ready,” Todd said. Maybe they thought they’d heard it all before. Todd, who was unhappy Valentine was banning smoking in the clubhouse, casually dismissed the new-ish manager’s breath of fresh air aspirations: “That’s the way every camp starts. Then, after the first day, it’s chaos.” On the other hand, the less-established Butch Huskey anticipated a leader who “relates to young players better than Dallas did” and would stress the basics. “We got beat on the fundamentals last year more than anything.”

Depending on who you asked circa Valentine’s Day 1997, Bobby V’s managerial prowess might as well have been that box of chocolates of which Forrest Gump had been so fond a few years before. Maybe we didn’t know what we were going to get out of the first Met squad he molded rather than inherited. Yet between two managers in 1996, the Mets lost 91 games, and it was hard to spot any serious personnel upgrades in the ensuing offseason. A hundred losses? It didn’t seem out of the realm of possibility.

[4]Still, here was Valentine, in the midst of attempting to change Met culture, being a good sport about the cake. And here were Franco and Hundley having a laugh at their manager’s expense despite being the constants of six consecutive seasons that left little to laugh about. I saw the coverage in the papers the day after Valentine went down and kind of wondered, amid the in-his-face quality of the joke, why any of this was supposed to be funny.

[4]Still, here was Valentine, in the midst of attempting to change Met culture, being a good sport about the cake. And here were Franco and Hundley having a laugh at their manager’s expense despite being the constants of six consecutive seasons that left little to laugh about. I saw the coverage in the papers the day after Valentine went down and kind of wondered, amid the in-his-face quality of the joke, why any of this was supposed to be funny.

On Opening Day, there was even less that rated a chuckle. The Mets started the season on the West Coast so as to avoid the Northeastern climate. First up were the Padres, on April 1. Another too on-the-nose occasion for what was about to transpire. Hundley’s two-run homer in the top of the third staked Pete Harnisch to a 2-0 lead. Gilkey added two more via a bases-loaded single. Mets up, 4-0, going to the bottom of the sixth. Looks like one sweet Opening Day, huh?

APRIL FOOLS!

Harnisch gives up a homer to Chris Gomez to lead off the inning. Hey, that’ll happen. Rickey Henderson follows directly with another home run. Well, he is Rickey Henderson. Quilvio Veras, a former Mets farmhand, homers right after Henderson. The 4-0 lead is now 4-3, and no amount of Southern California warmth can cut the chill infiltrating the visitors’ dugout. Valentine removes Harnisch in favor of Yorkis Perez. The Padre bats are very much in favor of the decision, as another run is manufactured in the course of three hitters. Tie game. Toby Borland comes on to pitch; he walks three of his four opponents, and now it’s 5-4, Padres. The fourth pitcher of the sixth, Barry Manuel, enters. Barry finishes the inning by permitting six more runs en route to the third out.

An eleven-run inning. The Mets, regardless of urban myth, don’t win every Opening Day. The California trip is mostly a disaster. The club goes 3-6 in San Diego, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. They fly home to commence the home portion of their schedule on Saturday the 12th. Why on a Saturday? Because the other New York team had also begun its season out west and slated its Home Opener for Friday, and Mets management didn’t want their big event completely overwhelmed by a flag-raising on the other side of town. Their thanks for ceding the spotlight? A rainout Saturday, a de facto Home Opening Day doubleheader sweep at the hands of the Giants Sunday (attracting fewer than 22,000), and a Monday afternoon defeat to shove the Mets out of the gate at 3-9. Only in 1962 and 1964 had the Mets been worse after a dozen games. Those were hundred-loss seasons, to be sure.

If you were considering purchasing stock in the Mets’ chances, it was a classic buy-low inflection point. If you were a savvy investor, you might have noticed a couple of positive indicators. John Olerud, the faded batting champion the Blue Jays were happy to pawn off on the Mets, took a liking to National League pitching, posting a .373 batting average (and quickly replacing previous first baseman Rico Brogna as a fan favorite). Journeyman Rick Reed, noted mostly for having participated in MLB’s replacement player farce a couple of Springs earlier while on a minor league contract with the Reds (his mom needed insulin, he patiently explained), emerged as an effective control artist on the Western swing, delivering twelve unrewarded scoreless innings as a starter and reliever. Valentine had the 32-year-old in Norfolk the season before and saw him as something more than a Quadruple-A hanger-on. And if you liked the idea of a team capable of rising to something approximating a big moment, the next game the 3-9 Mets played was the first Jackie Robinson Night. Shea Stadium was sold out. President Clinton was on hand. In honor of the fiftieth anniversary of Robinson shattering baseball’s color line, No. 42 was announced midgame as henceforth retired throughout Major League Baseball. Not incidentally, the Mets shut out the Dodgers, 5-0.

OK, so the Mets were now 4-9. The next day, they barely managed to avoid being no-hit by Pedro Astacio and three L.A. relievers, leaving them 4-10. These numbers defied the notion that a turnaround was nigh. But when the Mets next played, they beat a team clearly worse than them, the 0-13 Cubs. Make that the 0-14 Cubs, when the 6-10 Mets did it again. Finally, Chicago took two from New York, which wasn’t good, but it did help lead Bobby V to a critical lineup alteration.

On April 22, with the Reds in town, Valentine installed Edgardo Alfonzo at third base in the field and the two-hole in the lineup. Huskey had received the bulk of the playing time at the Mets’ perpetually troublesome hot corner. He’d already accumulated six errors, while batting .149. Fonzie, as he was referred to when he was referred to at all, was somehow hitting worse in limited action — .129 — but had earned a reputation for headiness during his utilityman apprenticeship under Green. The 23-year-old’s first chance to prove himself offensively came against longtime Met nemesis John Smiley with the bases loaded in the fourth inning. Alfonzo lined a three-run double into the right-center gap, providing plenty of cushion for Reed to go the distance and beat his previous organization, 7-2. The next night, Fonzie was in there again. He went 3-for-3, as the Mets won, 10-2. It wasn’t precisely a coronation, but it was close enough. For the rest of the season, as long as injuries didn’t skew form, Alfonzo regularly batted second and regularly played third.

Fonzie at third. Oly at first. Reeder in the rotation. Nicknames as signs of familiarity and affection. The Bobby Valentine Mets were beginning to differentiate themselves from what preceded them, save for the matter of the won and lost columns. Two losses to the Expos had cooled the building momentum from the two wins over the Reds. They were 8-14 entering their Sunday finale at Olympic Stadium on April 27, the product of two weeks of .500 ball since their miserable start. Not a single team in Mets history to have started 8-14 or worse after 22 games — there were ten of them to this point — had finished with a winning record. Trendlines didn’t suggest this one was going to be any different, and a 3-3 tie yielded no resolution through nine in Canada. In the top of the tenth, however, Rey Ordoñez, he of the glittering glove and unremarkable bat, stroked a single into right field with the sacks full. Two runners came home. John Franco protected the 5-3 lead. The Mets left Montreal with a one-game winning streak.

Hindsight would reveal it as the biggest one-game winning streak since the dawn of the decade. One win in Montreal became four in a row and six of seven. A case of the ol’ win-one/lose-ones frustrated efforts to touch .500, but the Mets shook that off in due order. On May 10, a surging Bobby Jones, who’d been around quietly grinding since 1993, combined with Franco on a three-hit shutout in St. Louis. Jones was 6-2. The Mets were 18-18. The next day, they rode consecutive ninth-inning pinch-homers from Carl Everett and Huskey to a 6-4 lead, an edge again handed off to Franco, who once more secured the victory. The 1997 Mets were 19-18.

It was only the beginning. Four in a row. Seven of nine. By the time June got going, the Mets were 31-23. A third of the season was in the books. The standings listed the Mets as a half-game out of the Wild Card.

I was in heaven.

Granted, after what the Nineties had been for the Mets, my version of heaven didn’t have much of a barrier to entry. Maybe this wasn’t 1969 or 1984, but for me, it might as well have been. I was at least a few months too young [5] to comprehend 1969 while it was becoming 1969. I was a few too many miles removed [6] from New York to completely absorb 1984 becoming 1984. As come-out-of-nowhere seasons went, 1997 was the one that grabbed me and embraced me from the second its arms began to widen. I hugged it right back.

[7]Every morning with the papers was a thrill. Every morning measuring the distance between us and the Marlins — cosplaying as a large-market, high-payroll powerhouse — was an obsession. Every night that there was Mets baseball, there was little else I thought about. Where once the Mets offered emptiness, they now created possibility. I loved Oly. I loved Reeder. I loved Fonzie like I’d never loved a position player in my life. I adored everybody on the 1997 Mets. I adored adjusting my worldview from hoping the Mets might win their next game to believing the Mets could win their next game (to intermittently expecting they’d win). I revered Bobby Valentine, who seemed to get everybody into games and fill them with whatever it took to come through in those games, particularly late in those games. I appreciated his instilling in his charges an attitude that the biggest game the team was going to play this year was the one right in front of them, because it was “the only one we’re playing,” and preaching, “It’s not the best team that wins, it’s the team that plays best.” I didn’t care what step he stood on. I didn’t care that a player here or a reporter there let it be known he could be a bit much. I didn’t mind his riling up the opposition. Bobby Valentine was a terrific manager.

[7]Every morning with the papers was a thrill. Every morning measuring the distance between us and the Marlins — cosplaying as a large-market, high-payroll powerhouse — was an obsession. Every night that there was Mets baseball, there was little else I thought about. Where once the Mets offered emptiness, they now created possibility. I loved Oly. I loved Reeder. I loved Fonzie like I’d never loved a position player in my life. I adored everybody on the 1997 Mets. I adored adjusting my worldview from hoping the Mets might win their next game to believing the Mets could win their next game (to intermittently expecting they’d win). I revered Bobby Valentine, who seemed to get everybody into games and fill them with whatever it took to come through in those games, particularly late in those games. I appreciated his instilling in his charges an attitude that the biggest game the team was going to play this year was the one right in front of them, because it was “the only one we’re playing,” and preaching, “It’s not the best team that wins, it’s the team that plays best.” I didn’t care what step he stood on. I didn’t care that a player here or a reporter there let it be known he could be a bit much. I didn’t mind his riling up the opposition. Bobby Valentine was a terrific manager.

And we haven’t even gotten to June 16 yet.

The Mets of 1969 had never won before. At all. When they took their first giant steps in May and June, however, they were already the team in their city. New York was a National League town; Shea retained its Space Age sheen and accompanying sense of joie de vivre; and there wasn’t much in the way of municipal competition for share of baseball mind. The Yankees had their fans, but not as many as the Mets. The remainder of 1969 would ensure the balance would tilt irreversibly toward the Mets not just for the rest of that Amazin’ year, but well into the 1970s. They’d have to tear down, rebuild, and reopen Yankee Stadium in 1976 to redirect attendance in the other direction…and the Mets would have to be run into the ground of their own volition.

Not only did the 1984 Mets climb out of their self-inflicted 1977-1983 wreckage and up the National League East standings, they nudged New York’s National League rooting muscles awake. The Yankees, despite having their hopes mauled by the rampaging Tigers, weren’t dismal over the course of ’84, but they failed to any longer be as compelling as they had been when winning the back pages of the late 1970s and early 1980s. The Metropolitan Area was due for a sea change. Davey Johnson’s Mets swept in and swept aside that other team, becoming the “A” story of every season for seasons to come.

I’d love to report that the 1997 Mets’ unexpected success had the same long-term impact on the local baseball scene. It didn’t. The Yankees were in their latest imperial phase and weren’t going anywhere. Defending world champions. Young, homegrown core. Enough resources and wherewithal to buy stars as needed. Steinbrenner finally figuring out how to be Steinbrenner to beneficial effect for his enterprise. They constructed a wall of perception the Mets of that period were never going to crack. That was the one piece missing from this segment of the 1969-1984-1997 triad. There’s never a bad time to start getting good, yet you might say we waited a tad too long to ascend toward something special if we were going to take back our town. I’m still waiting on the next sea change.

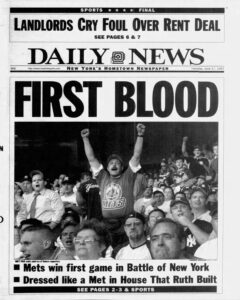

[8]Oh, but not on June 16, 1997. On June 16, 1997, we were it, baby. We were in the Bronx for a latter-day incarnation of the Mayor’s Trophy Game, except it wasn’t the Mayor’s Trophy Game. It was an actual game in the middle portion of the schedule. It was Interleague play, one of those theoretical what-ifs I’d read about in Baseball Digest as a kid. What if the National League’s teams played the American League’s teams in the regular season? It was right there with predictions that all games would be played under domes, on artificial turf, on other planets. I didn’t think much of the what-if, ’cause I didn’t believe it would ever happen.

[8]Oh, but not on June 16, 1997. On June 16, 1997, we were it, baby. We were in the Bronx for a latter-day incarnation of the Mayor’s Trophy Game, except it wasn’t the Mayor’s Trophy Game. It was an actual game in the middle portion of the schedule. It was Interleague play, one of those theoretical what-ifs I’d read about in Baseball Digest as a kid. What if the National League’s teams played the American League’s teams in the regular season? It was right there with predictions that all games would be played under domes, on artificial turf, on other planets. I didn’t think much of the what-if, ’cause I didn’t believe it would ever happen.

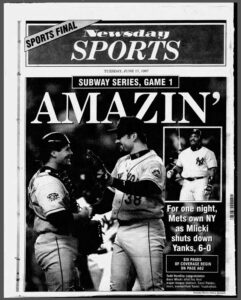

[9]It happened. It happened first the prior Friday, at Shea, the Mets hosting the Red Sox, its own historical overtones implicit. The Mets lost two of three to Boston. A mere undercard to Monday night, June 16, Mets at Yankees, the first of a three-game series in a rivalry that used to be limited to exhibitions and imagination. What if the Mets played the Yankees for real?

[9]It happened. It happened first the prior Friday, at Shea, the Mets hosting the Red Sox, its own historical overtones implicit. The Mets lost two of three to Boston. A mere undercard to Monday night, June 16, Mets at Yankees, the first of a three-game series in a rivalry that used to be limited to exhibitions and imagination. What if the Mets played the Yankees for real?

What if the Mets beat the Yankees like it was no big deal? Of course it was a very big deal, but let’s remember that one baseball game is one baseball game. Any one team can beat another. The Mets entered this Monday night 36-30, the Yankees 37-29. Two teams within a game of each other. Logic would tell you that’s a pick ’em situation.

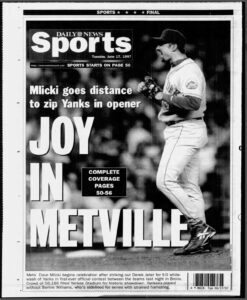

[10]So why was it treated as a shock, for better and less better, that the Mets beat the Yankees the first time they played a game that counted? Mets 6 Yankees 0. One of 162. But one above all. The novelty of it — first game between New York teams that got kept track of since the Brooklyn Dodgers couldn’t quite repeat as world champs in 1956 — explains a lot of it, maybe most of it. Erratic Dave Mlicki’s role as crafter of a complete game shutout also can’t be diminished. If this was the best performance of Mlicki’s career, eternal kudos to the Ohio native for choosing June 16, 1997, to share it with us. Had baseball shut down prior to the scheduled first pitch of the next night, we’d always have the all-time edge in intracity affairs, and I’d always have the memory of a pair of Yankee fan co-workers greeting my sunny “good morning!” of June 17 with expletives.

[10]So why was it treated as a shock, for better and less better, that the Mets beat the Yankees the first time they played a game that counted? Mets 6 Yankees 0. One of 162. But one above all. The novelty of it — first game between New York teams that got kept track of since the Brooklyn Dodgers couldn’t quite repeat as world champs in 1956 — explains a lot of it, maybe most of it. Erratic Dave Mlicki’s role as crafter of a complete game shutout also can’t be diminished. If this was the best performance of Mlicki’s career, eternal kudos to the Ohio native for choosing June 16, 1997, to share it with us. Had baseball shut down prior to the scheduled first pitch of the next night, we’d always have the all-time edge in intracity affairs, and I’d always have the memory of a pair of Yankee fan co-workers greeting my sunny “good morning!” of June 17 with expletives.

A tad bothersome in the moment and in memory to me was the idea that everybody should have been shocked the New York Mets could win a single baseball game from the New York Yankees — with audible vocal support outside Queens, no less. Never mind any team being capable of beating any team on a given night. The New York Mets were now 37-30, same as the almighty New York Yankees. They were contending in their league, and we were contending in ours.

[11]No need for shock. But plenty of reason for excitement. After the Subway Series, the Mets reeled off six consecutive wins, every one of them spine-tingling in its way. The last of them came against another foe that loomed as larger than life: the Atlanta Braves. The last time the Mets faced the Braves with much on the line for each of them, Nolan Ryan had come out of the bullpen to sew up the pennant. We had hewed to our respective lanes until the Braves were realigned into the NL East, another incident illustrative of bad timing. The once-sorry Braves had established their own imperial phase, coming into 1997 as winner of five division titles since 1991. It didn’t matter if they were West or East. They were Atlanta, and they’d been playing in a league above the Mets for years.

[11]No need for shock. But plenty of reason for excitement. After the Subway Series, the Mets reeled off six consecutive wins, every one of them spine-tingling in its way. The last of them came against another foe that loomed as larger than life: the Atlanta Braves. The last time the Mets faced the Braves with much on the line for each of them, Nolan Ryan had come out of the bullpen to sew up the pennant. We had hewed to our respective lanes until the Braves were realigned into the NL East, another incident illustrative of bad timing. The once-sorry Braves had established their own imperial phase, coming into 1997 as winner of five division titles since 1991. It didn’t matter if they were West or East. They were Atlanta, and they’d been playing in a league above the Mets for years.

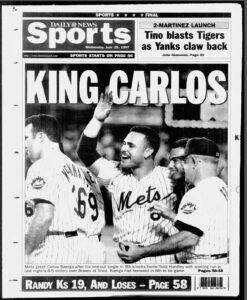

Not this June, though. The Mets took two of three from the Braves at Shea. It was the second of them that stands out. Somebody should have saved the tape. It’s the essence of a Mets Classic. Mets tie it at three in the sixth. Braves nose ahead by two in the seventh. Carlos Baerga homers with Carl Everett on to tie it anew in the eighth. Ex-Brave Greg McMichael strands his former teammates on all three bases to escape the top of the ninth. Baerga walks it off, singling in Everett. Jason, I learn the next day via e-mail, stood on his seat and high-fived a total stranger taking the same stance as the winning run crossed the plate.

The night “was made big by Baerga,” Noble declared in Newsday. Carlos had slid from key member of the Tribe when Cleveland rose to prominence a few years earlier to utterly dispensable by the Cuyahoga. We got him the previous summer along with Alvaro Espinoza in exchange for Jeff Kent and Jose Vizcaino, one of those change-of-scenery trades in which maybe somebody will regain their vitality. Nothing of a sort happened for Baerga in New York in 1996 (.193 in 26 games), and his 1997 limped to an unpromising start, not unlike that of his team. Now? As Baerga went, so went the Mets, and vice-versa.

King Carlos, the back page of the Daily News crowned him. He was overjoyed to have bested “the team of the ’90s,” a.k.a. the franchise that denied his Indians a world title (and maybe that title) two Octobers before. His “dream,” he added, was to “have this team in the playoffs, playing them again. I’d like to get a couple of hits and take this team to a championship.”

[12]This is how the Mets talked and thought behind somebody else’s castoff in the middle of the year nobody saw coming. “Baerga is growing as the Mets’ primary figure,” Noble wrote. “He’s becoming our emotional leader,” McMichael agreed. “It does make you think anything is possible when we have Carlos doing it,” Huskey affirmed. “There’s no better man to have up there. He’s changing the way we think.”

[12]This is how the Mets talked and thought behind somebody else’s castoff in the middle of the year nobody saw coming. “Baerga is growing as the Mets’ primary figure,” Noble wrote. “He’s becoming our emotional leader,” McMichael agreed. “It does make you think anything is possible when we have Carlos doing it,” Huskey affirmed. “There’s no better man to have up there. He’s changing the way we think.”

And what were the Mets thinking as they suddenly sat four games out of first place, not to mention a game-and-a-half from the Wild Card? Elder statesman Franco saw the East in play: “I’d take it if we won the division. Why not think that way? We’re close enough and we’re playing well enough that we can think about both. But why not think about the division?”

The revival of Baerga and Olerud, alongside the sustained emergence of Reed, Jones, and Alfonzo, plus contributions from the likes of Everett, Matt Franco, Jason Hardtke, Cory Lidle and, well, just about everybody who wasn’t one of those Opening Day relievers, made anything and everything seem possible as summer set in. Perhaps the Met-themed back pages weren’t plentiful, given who else locally was already established as a postseason aspirant, and maybe the turnstiles in Flushing weren’t clicking with the desired velocity — none of the three Brave games drew 30,000 — but if you knew, you knew, and you jumped up on a seat. “It’s time to come out and see what’s going on,” fireman Franco urged. He didn’t intend to save games as part of New York’s best-kept open secret, a hidden gem in plain sight.

Yet that might have been the accidental charm of 1997. We who knew did know. We had persevered from 1991 through 1996 with zero reward and commensurate buzz. If you were still a Mets fan coming into 1997 despite those around you congratulating themselves for boarding the Bronx bandwagon, you recognized the beauty of a team scrapping away daily and nightly, a team that forgot it was supposed to be doomed, a team that eventually lost sight of first place (curse that team of the ’90s) but stayed vigilant and diligent in pursuit of the other potential playoff berth. The Wild Card had been inaugurated as a prize in strike-shortened 1994, doled out in earnest for the first time in strike-solved 1995. The Mets fell too far off the pace to convince a fan it could be pursued in earnest in either of those years. For a hot minute in July of ’96, just before Baerga came over, the Mets drew kind of close. Then they fell away, spiraling out of even conceptual contention, ultimately getting Green fired.

That all seemed so long ago by July of 1997. The Mets were in this thing in the present, staying on Florida’s heels, sticking it out to eighth and ninth and extra innings, storming from behind over and over. We changed GMs midstream, swapping out Joe McIlvaine (who helped get us here) for Steve Phillips for “skill set” reasons that seemed murky. Phillips engineered a six-player trade that I didn’t quite grasp, either. Lance Johnson, possessor of 1996’s wonderbat, went to the Cubs in the company of hardy starter Mark Clark and valuable bench guy Manny Alexander, and in return came back a less exciting center fielder, Brian McRae, and two relievers who weren’t necessarily getting it done in Chicago, Mel Rojas and Turk Wendell. I took it on faith that this ilk of dice roll is what contenders who need a little something try when July becomes August. It had been so long since I’d rooted for one, I wasn’t sure.

The slightly retooled Mets continued to have their moments, but they also stalled a bit as summer grew late. The Marlins were within reach, but they had a lot of talent and enough of a lead to fend us off. I still believed we’d catch them. We were the 1997 Mets.

Yes, we. I was too connected to this team to view them with detachment. I’d exchanged my own hellacious high-fives with total strangers, at Shea and online. I’d shivered in the Upper Deck when the Mets did Jackie Robinson Night proud, I’d disregarded Ed Coleman’s warnings that a rainout was imminent in order to sit in the emptiest (but perfectly dry) Field Level I’d ever encountered one early-May Saturday. There were so few people there that I could pick myself out when Sportschannel aired its condensed version that night. I’d sweltered sweetly on a Sunday afternoon until Everett sent us home 12-9 winners in ten. When I couldn’t be at the ballpark, I was tuned in like I hadn’t been tuned in in years…and it’s not like I had ever tuned the Mets out.

This was different, though. This was the Mets as a way of life. As my way of life. Of all the branches I can trace that explain why I’ve been the Mets fan I’ve been and have stayed the Mets fan I stay, the one that stems forward from 1997 may be the sturdiest. In 1997, the Mets provided me a backbeat that’s remained steady ever since. The volume now and then lowers, but it’s always there. I watched and listened to games in the lousy years that preceded it, but that was me watching and listening to an entity distinct from myself. The 1997 Mets and I were intertwined. We were in this thing together. Backbeat and forefront. A tone was set. Priorities were reset, then set in stone. All in and locked in.

I was 34 that year. The last time the Mets were good, I was 27, still riding the Met high that arrived when I was 21. In my late twenties and early thirties, I’d had decent excuse to drift away to a state of mind where the Mets existed but mattered only so much. Marriage. Work. Cats. Maturity, possibly. I had never stopped being a Mets fan, yet it still represented a great leap forward to get where I got in 1997 from where I’d been in the desolation that developed after Davey and before Bobby V. I liked this new, more intense level of fandom that I found. Or did it find me? Either way, my foothold in it grew firm, especially in the succeeding half-decade. I’m still more or less there.

The Marlins slipped away from us in September. I think I knew deep down in August we weren’t going to reel in that Wild Card, but as long as I could rationally reason we were about get hot and they were about to go cold, I never gave up. The baseline of playoff chase anxiety that usually informs a fighting final month was mostly absent. They’d already given me so much, they couldn’t give me agita. I will admit that while watching from home on September 13, I came as close to giving up on the year as I could. We were down to the Expos at Shea, 6-0, heading to the bottom of the ninth. We’d cut it to 6-2 and loaded the bases. Everett was up and belted a long fly ball just foul. You don’t get one of those and then get the chance to straighten it out.

Before Carl could swing again, my wife reminded mopey me, “You Gotta Believe,” which itself felt like a miracle. Stephanie had been supportive enough of my obsessiveness through the summer, but this was stepping up down the stretch. She’d never quoted Tug McGraw to me before.

Reminded how to act by an unlikely source, I Believed. Everett got another pitch he liked and sent it soaring out of Shea for a game-tying grand slam. I’ve been blessed to witness more dramatic, more impactful clutch connections go deep since, including one that couldn’t have been more dramatic or impactful on the final day of the most recent regular season. I don’t know that any of them has moved me as much as Carl Everett’s grand slam. A couple of innings later, Gilkey walloped the game-winner. Somebody was gonna do it. We weren’t losing The Carl Everett Game.

Likewise, I wasn’t missing the final game of the year, September 28. Bought a ticket from a guy outside the ballpark looking to get rid of one, maybe 15 rows behind home plate. Imagine somebody not wanting to be at the final Mets game of 1997. Paid attendance indicates roughly half of Shea Stadium’s seats went unoccupied or at least unsold, par for a year when the Mets outdrew only four National League teams. Somebody must have inadvertently clicked “private” on the season’s settings.

We weren’t losing on Closing Day, either. The division champion Braves were the opponents, eternally tuning up for the playoffs. We’d been eliminated at the beginning of the week, after leaving Miami with three wins in a four-game series. They thought they’d clinch against us. We didn’t allow them to, yet another sign that these Mets would stand tall to the very end. “There’s nothing to be sorry about,” the writer Jonathan Yardley told his wife as she attempted to comfort him as his Orioles faced their final outs in the World Series of 1979, the year he plunged head over heels in love with his baseball team. “It was a wonderful summer.”

In sports talk radio parlance, you’d immediately sign for a season like that. More than the collection of statistics that encouraged me toward 1998 and beyond, I had the memories of players who’d melded into one inspirational unit. They inspired me to stick with them night after night and day after day for my own wonderful summer. It can be dangerous to decide who’s a “good guy” or a “bad guy” from a distance, but my 1997 Mets, together, felt like the good guys. They even wore those white “ice cream” caps for a spell to signal their cause was righteous. “On other teams I played on,” middle reliever and spot starter Brian Bohanon said at September’s end, “White guys stuck with the White guys, Latin guys stuck with Latin guys, and Black guys stuck with Black guys. Here, everyone mixes with everyone. That’s one of the things that makes this team different.”

The collection of statistics was pretty good, too. Olerud came into Game 162 in search of his hundredth RBI. He got it and then some. John finished at .294, Carlos at .284, Butch at .287. Ordoñez didn’t hit, but he tracked down his first Gold Glove. Alfonzo — Fonzie forevermore — fielded exquisitely at third and batted .315, earning scattered MVP support. Reed — Reeder forevermore — shunted aside the replacement player storyline by turning irreplaceable in the rotation. His ERA of 2.89 was sixth-best in the league. Bobby Jones cooled off in the second half, but he would always have his All-Star appearance, the one in which he struck out Ken Griffey and Mark McGwire in succession. John Franco posted 36 saves. Todd Hundley belted 30 home runs.

The sum of Met parts amounted to 88 wins, 17 more than the year before and the most the club had notched since 1990; they went 80-60 after that 8-14 start. The sum of Met parts finished four games behind the hastily constructed Marlins, who went on to capture the World Series and then be disassembled in a blink; had geography been more malleable, the Mets’ winning percentage would have been sufficient to clinch the NL Central and the AL Central (as long as Interleague play existed, we’re entitled to put forth broad hypotheticals). The sum of Met parts did not go gently into winter. Not only did they take care of the Braves for Win No. 88, but they and we engaged in one final hug. In the ninth inning on September 28, those of us who had the good sense to fill some Shea Stadium seats stood and applauded and chanted LET’S GO METS. We started with one out. We kept it going through the third out and maintained our expression of gratitude as the players eschewed handshakes and threw their arms around each other. Rather than leave the field, everyone mixed with everyone, turned to us, and acknowledged us. We kept acknowledging them. Conscious of Jason’s June example, I climbed atop my seat. Others did the same. How had I never noticed seat-climbing was a thing?

![]() [13]DiamondVision played a video, cramming as many spectacular moments as could fit the length of “Reach” by Gloria Estefan. I was already crying before the first clip; I was drowning in tears by the conclusion. I came to the game solo, but I wasn’t alone in this regard, not in the stands and not on the field. “This was more emotional for me than winning in Cleveland, the way we played together,” Baerga insisted. Valentine was affected, too: “I had some goose bumps. I had some emotion. There were so many images going through my head.” Me, I saw no need to dry out until my train ride home was complete. The waterworks resumed once I walked in the door to tell Stephanie about what I experienced.

[13]DiamondVision played a video, cramming as many spectacular moments as could fit the length of “Reach” by Gloria Estefan. I was already crying before the first clip; I was drowning in tears by the conclusion. I came to the game solo, but I wasn’t alone in this regard, not in the stands and not on the field. “This was more emotional for me than winning in Cleveland, the way we played together,” Baerga insisted. Valentine was affected, too: “I had some goose bumps. I had some emotion. There were so many images going through my head.” Me, I saw no need to dry out until my train ride home was complete. The waterworks resumed once I walked in the door to tell Stephanie about what I experienced.

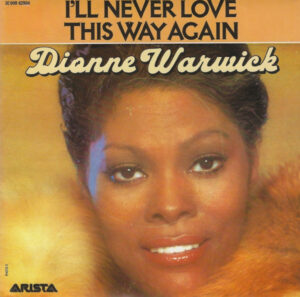

[14]I know I’ll never love this way again. I’m good with that. No other season can take me by surprise in the best manner possible. I’ve lived a few seasons in this century when the Mets far exceeded expectations (mine and everybody’s), and they excited me in their own fashion, but my path was already paved. When a 2015 or 2019 or 2024 hops out from behind a bush, slaps me on the back, and shouts “SURPRISE!” I no more than modestly startle. I intrinsically understand that invigorating Met years — not just uplifting Met endings — can come out of nowhere. Despite 1969 and 1984, I don’t think I truly understood that before 1997. Similarly, I don’t go into years that are projected as dim completely convinced the lights will stay off. I can be cynical and pessimistic, but, thanks to 1997, I see no need to predict how bad things might go. Or how good. If somebody wants to tell me in advance that the Mets are going to lose 100 games or win 100 games, I’ll shrug. Let things be. See what happens. Feel what happens.

[14]I know I’ll never love this way again. I’m good with that. No other season can take me by surprise in the best manner possible. I’ve lived a few seasons in this century when the Mets far exceeded expectations (mine and everybody’s), and they excited me in their own fashion, but my path was already paved. When a 2015 or 2019 or 2024 hops out from behind a bush, slaps me on the back, and shouts “SURPRISE!” I no more than modestly startle. I intrinsically understand that invigorating Met years — not just uplifting Met endings — can come out of nowhere. Despite 1969 and 1984, I don’t think I truly understood that before 1997. Similarly, I don’t go into years that are projected as dim completely convinced the lights will stay off. I can be cynical and pessimistic, but, thanks to 1997, I see no need to predict how bad things might go. Or how good. If somebody wants to tell me in advance that the Mets are going to lose 100 games or win 100 games, I’ll shrug. Let things be. See what happens. Feel what happens.

[15]At a glance, what happened in 1997 was an 88-74 team didn’t make the playoffs when playoff spots weren’t as plentiful as they would later become. That, I suppose, is why the 1997 Mets built no historical profile and encompass no historical cachet. They were close to October, but not achingly close. They had productive players, but no Piazza. The rebirth of the franchise as a legitimate on-field entity, not to mention the resumption of the fans’ ability to take the team seriously, definitely occurred, but the emotional/competitive payoff was a couple of years from bearing tangible fruit. Their achievement appears pedestrian by numbers. Their vibe preceded the sorts of mechanisms that would put the feelings they generated in their time on an easily accessible loop. The Mlicki shutout comes up some summers on the eve of an impending Subway Series, but nothing else tends to get mentioned widely. Our Mets-coded radio and TV guys who’ve seen it all and reference plenty never bring up 1997 to illustrate a point or relate an anecdote. The years directly after it, yes, but not the year that turned the team around. They’ve called a lot of ballgames, so perhaps it’s excusable that one particular year’s worth that doesn’t have a place on a banner and happened quite a while ago falls by the wayside…perhaps.

[15]At a glance, what happened in 1997 was an 88-74 team didn’t make the playoffs when playoff spots weren’t as plentiful as they would later become. That, I suppose, is why the 1997 Mets built no historical profile and encompass no historical cachet. They were close to October, but not achingly close. They had productive players, but no Piazza. The rebirth of the franchise as a legitimate on-field entity, not to mention the resumption of the fans’ ability to take the team seriously, definitely occurred, but the emotional/competitive payoff was a couple of years from bearing tangible fruit. Their achievement appears pedestrian by numbers. Their vibe preceded the sorts of mechanisms that would put the feelings they generated in their time on an easily accessible loop. The Mlicki shutout comes up some summers on the eve of an impending Subway Series, but nothing else tends to get mentioned widely. Our Mets-coded radio and TV guys who’ve seen it all and reference plenty never bring up 1997 to illustrate a point or relate an anecdote. The years directly after it, yes, but not the year that turned the team around. They’ve called a lot of ballgames, so perhaps it’s excusable that one particular year’s worth that doesn’t have a place on a banner and happened quite a while ago falls by the wayside…perhaps.

I’ve come to mostly accept 1997’s undeserved obscurity as a badge of honor. Other seasons I hold comparably dear produced heftier accomplishments. This one, though, made the most of what it managed to do, even if it didn’t do quite as much. Pound for pound, that’s a title no other Mets season can ever take away from this one. Pound for pound, no other Mets season could ever give me more.

PREVIOUS ‘MY FAVORITE SEASONS’ INSTALLMENTS

Nos. 55-44: Lousy Seasons, Redeeming Features [16]

Nos. 43-34: Lookin’ for the Lights (That Silver Lining) [17]

Nos. 33-23: In the Middling Years [18]

Nos. 22-21: Affection in Anonymity [19]

No. 20: No Shirt, Sherlock [20]

No. 19: Not So Heavy Next Time [21]

No. 18: Honorably Discharged [22]

No. 17: Taken Down in Paradise City [23]

No. 16: Thin Degree of Separation [6]

No. 15: We Good? [24]

No. 14: This Thing Is On [25]

No. 13: One of Those Teams [26]

No. 12: (Weird) Dream Season [27]

No. 11: Hold On for One More Year [28]

No. 10: Retrospectively Happy Days [29]

No. 9: The September of My Youth [30]

No. 8: First Taste [5]

Nos. 7-5: Three of a Kind [31]