Baseball seasons run only so many games and so many months long. Yet if you’re lucky, they last forever. Also, if you’re a little unlucky after the fact, they stick around without a peer emerging to join them where you left them. The season that lands at No. 3 among MY FAVORITE SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT but surely gave me my hands-down favorite result did its best to set itself apart from anything that could have come after it. As far as I’m concerned, it’s done everything it’s had to do since its moment in the spotlight, even if it’s had to carry on with a status we never dreamed it would maintain for decades.

When it was coming along, we had dreamed only of the season it would give us when it was giving it to us. Boy, did it deliver.

3. 1986

It’s late one morning in May. I look up at a clock. It’s around 11:30. All I can think is, “Eight hours until the Mets game tonight.”

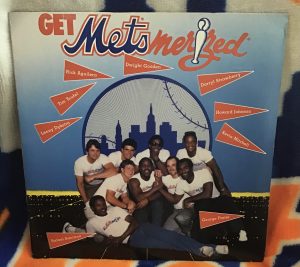

That was 1986 to me while it was going on. Watching the clock and waiting for the Mets equaled winning time. It occurs to me I didn’t have a lot else going on in my life that didn’t involve counting down to tonight’s game. It wasn’t an ideal route to personal fulfillment, waiting on a team of total strangers to report to work and make me ebullient, but I have no baseball-related regrets. I couldn’t stand for time to stand still because I wanted the game to get here. When the game got here, the Mets would probably win it, and by probably, I mean almost certainly. Once that game was won, I wanted another. The hours between wins dragged because the hours while the games were being won were, per the recording talents of George Foster, Metsmerizing.

With hindsight, maybe we’d appreciate those hours dragging. Don’t go away so quickly, season that had no Met precedent and has produced no worthy Met successor! What Mets fan wouldn’t want to continue living inside the baseball world that was 1986? If every season could be 1986, I wouldn’t argue with the outcome. But every season can’t be 1986. It would be too much to ask, maybe too much to take. Besides, how would you be able to differentiate it from all the other seasons?

With hindsight, maybe we’d appreciate those hours dragging. Don’t go away so quickly, season that had no Met precedent and has produced no worthy Met successor! What Mets fan wouldn’t want to continue living inside the baseball world that was 1986? If every season could be 1986, I wouldn’t argue with the outcome. But every season can’t be 1986. It would be too much to ask, maybe too much to take. Besides, how would you be able to differentiate it from all the other seasons?

In the great flight of Mets history, nothing else looks like 1986, and nothing else competes with 1986. That the Mets were celebrating their 25th anniversary all year brought the poles into stark relief (the kind Casey Stengel was usually saddled with in 1962 as soon he removed his starting pitcher). The full Met CV —108 regular-season wins; a divisional margin of 21½ games beyond any rival’s reach; an NLCS that couldn’t have been tighter for six games (but we won four of ’em); and a World Series that teetered on defeat but literally couldn’t be lost — has no remotely Metropolitan doppelgänger. There have been occasional subsequent invigorating roughshod rides through spring and summer that ultimately sagged in fall. There had been one previous world championship, but consensus pegs that one as a surprise for the ages, maybe the surprise for all ages. The 1986 Mets’ final acts versus Houston and Boston would have fit neatly in any highlight reel produced in miraculous 1969 or nearly as unbelievable 1973, but where they led was no stunner once you remembered these were the 1986 Mets. The 1986 Mets existed to win everything in sight, to take care of business like nobody’s business, with dominance and prominence, to say nothing of verve and panache.

That they did. Every day had you sneaking peeks at nearby clocks in anticipation. Looking forward to first pitches and last outs was how we lived. The Mets we rooted for were far and away the team in baseball. It took a little while to sink in that this was us. Eventually, we stopped pinching ourselves.

Yeah, we had a team like that once. Just once. Requesting another world championship after nearly forty years doesn’t seem greedy, but I doubt there can ever be another 1986 in this lifetime. My lifetime has encompassed one 1986. It oughta sate me. It makes me want a sequel. Sequels rarely measure up to the original, but I’d be willing to try another year like it on for size.

I wish us good luck casting the parts.

PART I — BECOMING THE 1986 METS IN 1986

Taking the long view, you’re usually safe starting with January 24, 1980, and the sale of the downtrodden Metropolitan Baseball Club of New York, Inc., to Doubleday & Company, fronted by Abner Doubleday descendant Nelson Doubleday, with Fred Wilpon on board holding a minority stake. They talk about reviving National League baseball in New York. They are greeted as liberators. They hire Frank Cashen, the GM in Baltimore from when they were a powerhouse (except for a five-game series in October of 1969), and Cashen goes to work. It doesn’t show in the standings for several seasons, but the farm system gets replenished. It begins to bloom. The crops are transported to New York. A manager from the Met minor leagues — also with Oriole pedigree — is promoted. Davey Johnson leads a young, talented team that has been augmented by a couple of imported superstars out of the utter wilderness and into serious contention. As 1986 arrives, the Mets are pretty much right there to greet it and grab it.

Taking the granular view, I’d say the 1986 Mets began to reveal they had become The 1986 Mets in boldface type on the dreary Monday evening of April 21, a rainy night in Flushing when paid attendance for the game against the Pirates (in those days actual turnstile count) was the lowest it would be all year. It was also the last time the Mets would enter action behind Pittsburgh in the NL East. Not that that was the yardstick anybody planned on using to measure 1986. Still, the Buccos, otherwise experiencing their own franchise doldrums, were 6-2. The Mets were 5-3. The Mets had been 2-3. Won their first two. Lost their next three. In retrospect, the first week of the season was the opening minutes of a first-round high-seed/low-seed March Madness matchup. The high seed comes out cold. The low seed hits a few baskets. Fans of the true blue blood programs understand there’s a long way to go in this game, not to mention tournament. Just give it a few more minutes.

Orange and blue blood didn’t necessarily circulate to our brains that way. Every game was precious. Every opponent was dangerous. The Pirates? The Pirates, coming off 104 losses the year before, had taken eight of eighteen from us, including three of six in September when us winning every game was imperative. We had built a one-game lead on St. Louis on September 12 after we bested them two out of three at Shea, yet finished three games in back of them. Down the stretch in 1985, the Cardinals dusted their cursed red feathers off and returned to winning. We futzed around and found out that you had to beat the Pirates and Cubs and Expos and Phillies, too. Gathering even a touch of panic at the idea of being 2-3 on April 14, or feeling a scintilla of anxiety that we were sitting in back of Pittsburgh starting play on April 21, required no hindsight to negate. Of course it was silly.

Or was it? We hadn’t learned how not to be nervous yet. Examining our roster and simply relaxing didn’t come easily. Not after coming close in 1984 and coming even closer in 1985. April wasn’t only close to March. It still carried the whiff of the near-misses of the previous two years. A certain strain of Mets madness infiltrated April’s air.

Then, on April 21, the Mets pulled into a second-place tie with the Pirates. Again, not the goal of the season whose competitive contours were still gestating, but significant for how we got there. The Mets trailed, 2-0, after a half-inning; 4-2 in the middle of the eighth; and 5-4 heading to the bottom of the ninth. Two comebacks, each on two-run homers off the scalding bats of demonstrative teammates — Gary Carter (.351) in the third, Ray Knight (.391) in the eighth — were poised to go to waste. Or would have in another year.

This wasn’t another year. This was 1986. This was Lenny Dykstra singling to lead off the home ninth, Kevin Mitchell bunting him to second, Tim Teufel doubling Dykstra home to tie the score at five apiece, and, within two batters, Carter driving home Teufel. Mets win, 6-5, in their first walkoff triumph of the young year. Now tied with Pittsburgh in the standings, the Mets would sweep the two-game set the next night; the season series versus Pittsburgh would turn out Mets 17 Pirates 1. No more futzing around. The Mets were on a five-game wining streak. An off day Wednesday, combined with a Cardinal loss, allowed us to nose into first place all by ourselves as we alighted at Busch Stadium for four critical games, Thursday through Sunday. Critical? In April? After last October, and our winning only two of three when we required one more in St. Louis in that season’s penultimate series, yes.

By the end of Sunday the 27th, once ex-Met Clint Hurdle lofted the last of new Met Bobby Ojeda’s pitches into star Met Darryl Strawberry’s glove, the Mets completed confirming they were The 1986 Mets. It hadn’t been a week since we trailed the Pirates, but now we led the team we had to lead by four-and-a-half games. We swept the Cardinals. I mean, we swept the hell out of the Cardinals. Thursday’s affair was another “nope, not this year”-style comeback, featuring Howard Johnson’s game-tying two-run homer off Todd Worrell in the ninth. Friday’s game was a pure whitewashing, Doc Gooden going the distance in a 9-0 breeze. Saturday’s game ended in one of those ninths that didn’t get away, with a 4-0 first-inning lead staying undisturbed until the final inning, when an eerily familiar Cardinal rally (three singles, one double and a sac bunt) fell short as Wally Backman turned the clutchest of 4-6-3 DPs. And Sunday’s game was the kind of coup de grâce that The 1986 Mets were honing into their specialty. Ojeda, picked up in an offseason trade we had no idea would bring us our winningest pitcher, threw a complete game. Rookie outfielder-third baseman Kevin Mitchell filled in at shortstop because Davey decided he could play it just fine. Mitchell homered, as did Teufel, the righthanded second baseman the Mets lacked in 1985 (Backman could do everything you wanted except handle lefties). These three added to Doc and Darryl and Keith and Gary and everybody else? The Mets were clearly improved. The Cardinals were clearly done.

The Mets left Missouri on a nine-game winning streak that grew to eleven. After a lone loss in Atlanta, they won another seven straight. The 2-3 Mets of April 14 morphed into the 20-4 Mets of May 10, a top seed turning all prospective NL East Cinderellas into pumpkins. Nobody in the division loomed as very concerning. Now and then, the Expos would present a theoretical obstacle — they drew as close as 2½ out on a West Coast afternoon in late May, and took two of three from us twice in June — but nothing insurmountable. We were playing from ahead in the standings from the instant we took the field in St. Louis on April 24, far ahead soon enough.

My favorite quote of the season came not from a Met, but from somebody who used to be one. In that second Expo series, at Shea, Montreal had pulled to within eight games of us after winning the first two. This was June 25, with well over a half-season remaining. The second-place Expos had their eyes on not just a sweep, but a statement. Instead, they saw a 2-0 lead in the Wednesday matinee finale turn into 5-2 loss. Instead of making up enough ground to get to within seven games of the Mets, they had fallen back to nine.

“Nine out is so damn close to ten,” their shortstop Hubie Brooks admitted after the loss. “Seven out is so damn close to five. I think we did good, but it’s too bad we couldn’t be better than nine out.”

I read that and thought, that’s it. That’s the concession speech. The Mets had played 68 of 162 games, and they had essentially clinched their division. To celebrate, they built a new eight-game winning streak. I guess this is where the Mets left zero doubt about being The 1986 Mets. Microspells of not stomping on opponents were capable of raising Mets fan eyebrows, because, well, our eyebrows hovered over eyes that had seen first-place Met clubs not finish on top in ’84 and ’85. You didn’t fully shake off your tendency to doubt, because you lived the previous years.

I read that and thought, that’s it. That’s the concession speech. The Mets had played 68 of 162 games, and they had essentially clinched their division. To celebrate, they built a new eight-game winning streak. I guess this is where the Mets left zero doubt about being The 1986 Mets. Microspells of not stomping on opponents were capable of raising Mets fan eyebrows, because, well, our eyebrows hovered over eyes that had seen first-place Met clubs not finish on top in ’84 and ’85. You didn’t fully shake off your tendency to doubt, because you lived the previous years.

But, really, you didn’t have any doubt.

PART II — BEING THE 1986 METS IN 1986

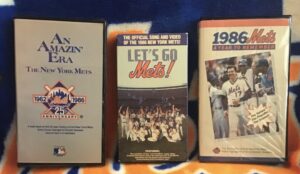

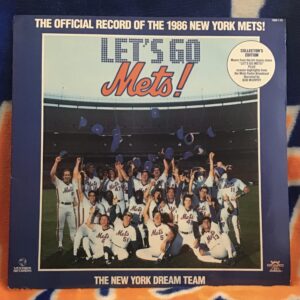

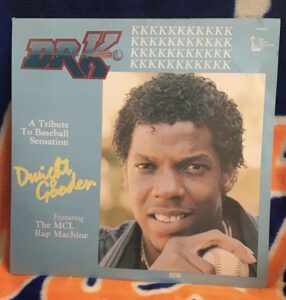

The above is the on-field stuff. The substance. What separates The 1986 Mets in the mind’s eye is the flair. The fights. The twelve-inch singles. The video productions. The curtain calls. The high-fives that would send the hands of mere mortals flying into Field Level. The aura. The top of the order. The heart of the order. The bench. The rotation. The back end of the bullpen. The speed. The power. The savvy. The rally caps. The hot foots/feet. The woman in the wedding dress brandishing a MARRY ME LENNY placard in the stands. The women and everything else we didn’t know about until the books and the documentaries came out much later. The best action in any sport being analyzed by the brightest mind in any booth, Tim McCarver’s. Ralph Kiner was in fine fettle, too, and Steve Zabriskie provided understated balance to McCarver’s brilliance and Kiner’s gleam. Bob Murphy was atop his game on WHN, paired with a worthy partner in Gary Thorne. Sure, some nights you had to put up with Fran Healy on Sportschannel, and no, they never did rustle up a dependable lefty specialist. Honestly, though, if those are your biggest problems, you don’t have problems.

I suppose the rest of the league didn’t love how the Mets took one game at a time and framed each as museum-quality. The 1986 Mets really loved being as good as they were. They didn’t act as if they’d been there before. Keith Hernandez had been to the mountaintop, as a Cardinal in 1982. Mex’s intensity was different from Kid’s; Carter blew the roof off open-air stadia with his exultations. Nobody besides Keith had won a World Series. These guys were all hungry to be the best and didn’t mind reveling in their status as the provisional kings of any mountain they scaled. It was infectious from a distance. We hadn’t made the playoffs in thirteen years. We had never carried around baseball’s best record or biggest lead day after day, week after week. They were excited? We were excited!

I suppose the rest of the league didn’t love how the Mets took one game at a time and framed each as museum-quality. The 1986 Mets really loved being as good as they were. They didn’t act as if they’d been there before. Keith Hernandez had been to the mountaintop, as a Cardinal in 1982. Mex’s intensity was different from Kid’s; Carter blew the roof off open-air stadia with his exultations. Nobody besides Keith had won a World Series. These guys were all hungry to be the best and didn’t mind reveling in their status as the provisional kings of any mountain they scaled. It was infectious from a distance. We hadn’t made the playoffs in thirteen years. We had never carried around baseball’s best record or biggest lead day after day, week after week. They were excited? We were excited!

Put another way, we had the teamwork to make the dream work.

Dissent could be discernible from an odd corner or two. For example, New York’s leading aficionado of underdogs Jimmy Breslin, who helped make the Original Mets as famous as could be for chronic failure via Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game?, registered a vote of protest against The 1986 Mets’ rampaging success. “[T]his year,” Breslin wrote in the News in August, “with the Mets winning so many games, it is embarrassing, for they resemble the old Yankees.” A month later, as the Mets closed in on their inevitable mathematical clinching, he expounded on the theme:

“When I sit alone, of course, I fanatically root for the Mets to lose. What do I need with a boring winner, with a first baseman, Hernandez, whom I don’t like personally but who can field the bunt and start a double play by throwing the lead runner out at third. My sports love still is the 1962 Mets, who lost 120 games, and who had as a first baseman, Marvin Throneberry. I still could see Throneberry in my mind on Friday night, Marvin Throneberry bent over, glove ready, eagerly looking at a ground ball, his mouth wide open, ready to bite the ball if it took a hop, eagerly watching, watching, watching as the ground ball went under his glove and through his legs and into right field.”

Mass huzzahs for the modern-day Mets ensued despite the columnist’s protestations. In the making-of video that accompanied the music video the Mets made in tribute to their awesomeness (because how else were you going to know the video had been made?), perhaps a member of Twisted Sister who wasn’t Dee Snider put it best: “Isn’t it nice to turn on the television and not have to worry that they may lose this evening — they’re still twenty games ahead! Think about that, they’re twenty games ahead, even if they lose once in a while. That’s what you call luxury! That’s almost as good as having a rent control apartment in Manhattan.”

Mass huzzahs for the modern-day Mets ensued despite the columnist’s protestations. In the making-of video that accompanied the music video the Mets made in tribute to their awesomeness (because how else were you going to know the video had been made?), perhaps a member of Twisted Sister who wasn’t Dee Snider put it best: “Isn’t it nice to turn on the television and not have to worry that they may lose this evening — they’re still twenty games ahead! Think about that, they’re twenty games ahead, even if they lose once in a while. That’s what you call luxury! That’s almost as good as having a rent control apartment in Manhattan.”

Let’s Go Mets Go, indeed.

PART III — STAYING THE 1986 METS IN 1986

One-hundred eight wins weren’t going to amount to a pitcher’s mound of beans if The 1986 Mets didn’t deliver in October. I don’t live in a world where they didn’t beat the Astros or the Red Sox, so I don’t know how I’d look back on them had they not brushed aside the best efforts of Bob Knepper and Dave Smith in Game Three of the National League Championship Series; or if Darryl Strawberry hadn’t connected off Nolan Ryan in Game Five, leading eventually to Gary Carter avenging Charlie Kerfeld in the twelfth inning; or if they hadn’t won…deep breath…Game Six. Ohmigod, Game Six. Ohmigod, and I don’t mean OMG. If anybody thought the Mets made 1986 look too easy for six months, Game Six in the Astrodome, culminating in a 7-6 win in sixteen innings and, oh yes, the National League pennant, reminded one and all that this team constantly created laurels rather than sat on them.

It could have gone the other way. The Astros could have held on in Game Three or Game Five or Game Six. They could have forced Game Seven, with Mike Scott on the hill, the Mets having every chance to look like fools swinging and missing at the ex-Met’s totally legitimate split-finger fastball whose movements weren’t enhanced by any foreign object, no sir. Or they could have sapped Scott of his strength and won the flag in seven. I wouldn’t have put anything past The 1986 Mets while they were being The 1986 Mets.

Not that I was pining to find out. Mets in six in the NLCS was sufficient. Bring on Boston!

Boston was brought on with a bit much velocity. The Mets endured the last of their Astrodome marathon on Wednesday, October 15. That gave them time to fly home (while tearing apart their airplane), rest up, work out, and, apparently, not be ready to play optimal ball on Saturday, October 18. Ron Darling pitched swell in Game One of the World Series. Bruce Hurst was a little sweller and won, 1-0. The next night, the hyped Dwight Gooden-Roger Clemens duel faltered on both ends, but faltered more for Gooden. A lot more. We lost, 9-3. Suddenly, the best team in the sport was down zero games to two in a best-of-seven situation.

What could have happened against Houston but didn’t was now in the process of happening against Boston. Then came Games Three and Four, and no frigging way was it going to happen. We won Game Three with ease (7-1), Game Four with essentially the same (6-2). Now we just had to win two out of a possible three. You’re gonna tell me we’re not gonna win two out of a possible three? That’s all we did all year. Two out of three fifty-four times in the regular season. Two out of three twice against the Astros. Hurst, the new Scott in practicality if not sandpaper, shut us down in Game Five, 4-2. So now we had to go back to Shea and win two of two. Shoot, we can win two of two.

First, however, we had to win one of one, because we trailed the World Series three games to two, meaning we faced a Game Six that literally could not be lost. Another Game Six? Didn’t we just do this in Houston? That was basically the greatest baseball game you thought you’d ever see, but it was ten days and a postseason lifetime ago. Plus, Scott or not, we’d led that series three games to two. This next Game Six had no hypothetical give to it. Could you imagine these robust, indefatigable, making-of-video-making Mets going down in six games to the Boston Red Sox? You didn’t have to imagine. It was happening in front of us for four-and-a-half innings, Red Sox 2 Mets 0, some dude parachuting from out of the sky, 24-game winner Clemens riding a no-hitter. Doubt was permissible in infinitesimal doses. We tied it in the fifth (phew!). We gave a one-run lead back in the seventh (damn!). We retied it in the eighth (yay!). We had a genuine chance to win it in the ninth, but didn’t (hmm…). We gave up two runs in the top of the tenth.

Expletive implied.

Suffice it to say, the bottom of the tenth of Game Six of the 1986 World Series took care of itself. The Red Sox led, 5-3, with two outs and no Mets on base. DiamondVision flickered discouraging word that it was all over. Yet The 1986 Mets, who’d already revealed and confirmed themselves The 1986 Mets, still maintained one out with which to play and a veritable Baseball Bugs conga line of individuals capable of making the most of a little leeway. Gary Carter singles. Kevin Mitchell singles. Ray Knight singles. A run scores. The Red Sox lead, 5-4. Mitchell is on third. Knight is on first. Former Met Calvin Schiraldi, the current Red Sox closer, is replaced by Bob Stanley, the Red Sox’ former closer. Mookie Wilson, drafted by the Mets on June 7, 1977, eight days before Tom Seaver (a current Red Sock) was traded, is up. Schiraldi throws a wild pitch. Mitchell dashes home. The game is tied. Knight moves up to second. Wilson continues to be up.

At this moment, within this at-bat, the World Series literally couldn’t be lost. Carter, Mitchell, Knight, Stanley and perhaps catcher Rich Gedman saw to that. It had all been on a beautiful, silver platter for the Red Sox, and the Mets took it away. Maybe in the eleventh inning, the situation would change, and the Mets literally could lose. But not in the tenth.

Wilson fouled off everything until he didn’t. His fair contact — a little roller up along first, per Vin Scully — was adequate for no more than a sprinter’s chance to beat out an infield base hit. If Mookie made it to first base safely, Knight would be on third, and Howard Johnson would be up. You couldn’t ask for more than that in the nanosecond you watched Mookie’s grounder trickle.

A nanosecond later, you got more than you asked for. You got the Red Sox’ first baseman, Bill Buckner, playing the part of Jimmy Breslin’s beau ideal of a first baseman, Marv Throneberry. The ground ball went under his glove and through his legs and into right field.

Mets 6 Red Sox 5. Series tied at three. Both teams have a chance to win this thing in seven.

But the Mets are going to win it. The Red Sox sure as hell aren’t going to. They take an early 3-0 lead off Darling, and Hurst holds us scoreless through five, but we’re The 1986 Mets. Fueled particularly by that trademark Mex brand of intensity (a tide-turning two-run single off Hurst after his brother gives him the high sign from the stands), we score three in the sixth. Then, two in the seventh, with Knight socking the tiebreaking home run over the wall. Boston gets two back in the top of the eighth, and that should make us uncomfortable, but nah. The Mets add two in the bottom of the eighth to make it 8-5. Jesse Orosco is on, just as he was in Houston when brass tacks were everywhere. He barely survived an Astro onslaught under the Dome. At Shea, nobody has to threaten him to throw nothing but sliders. He’s got this. So do Carter and Hernandez and Backman and Santana and Knight and Wilson and Dykstra and Strawberry. Davey has his platoons and his hunches, but here and now, you get the feeling he has precisely who he would want on the field to win a World Series.

Not that you wouldn’t trust any of the understudies right now. Everything about The 1986 Mets was, as Billy Joel reminded us regularly as summer seeped into fall, a matter of trust. Hearn the good-natured reserve. Heep the old pro. Mazzilli in his surprise second term. Elster, fresh from the bushes, smooth in the field. Teufel, not as much of a dirt-eater as Backman at second, but absolutely the slugger who walked off the Phillies in extras with a grand slam. Mitchell, brandishing numerous gloves to go with a potent bat. HoJo, who not only mortally wounded Worrell and the Redbirds in April, but won that crazy July game in Cincinnati, the one in which, as Breslin noticed, Hernandez fielded the bunt and started a double play by throwing the lead runner out at third…which happened to be manned by Carter. Howard Johnson had three 30-30 seasons in his near future. On the days and nights Mitchell didn’t start (85 games in all), the bench included 1989’s National League MVP. Come to think of it, on the nights Dykstra didn’t start (64 games in all), it had the guy who would in 1993 come in second to Barry Bonds for Most Valuable honors. Deep depth abounded just about everywhere you surveyed.

Darling (15-6) and McDowell (14-9, 22 saves) weren’t at their sharpest in this game, nor Gooden (17-6) in this series, but we wouldn’t be The 1986 Mets without any of them. And how about El Sid (16-6) holding the potentially crumbling fort in crucial middle relief? How about Ojeda (18-5) starting both Game Sixes and writing a new definition of withstand? How about Aguilera, if you allow yourself to look past the leadoff home run he allowed Dave Henderson in the tenth inning of Game Six? Aggie won ten games as the rotation’s forgotten man and kept Game Six of the NLCS scoreless for the three innings bridging Bobby O and Roger McD. How about Doug Sisk, despite the slump he sunk into in July of ’84 and seemed to come out of only intermittently? Sisk faced 312 batters in 1986 and gave up no home runs — no Met pitcher has come away from more encounters with batters in any season gopher-free. Hey, how about Randy Niemann, the personification of not the answer in lefty specializing? He did win his one start, in an August doubleheader, and Frank Cashen himself singled him out as a premier sprayer of champagne in Houston.

Darling (15-6) and McDowell (14-9, 22 saves) weren’t at their sharpest in this game, nor Gooden (17-6) in this series, but we wouldn’t be The 1986 Mets without any of them. And how about El Sid (16-6) holding the potentially crumbling fort in crucial middle relief? How about Ojeda (18-5) starting both Game Sixes and writing a new definition of withstand? How about Aguilera, if you allow yourself to look past the leadoff home run he allowed Dave Henderson in the tenth inning of Game Six? Aggie won ten games as the rotation’s forgotten man and kept Game Six of the NLCS scoreless for the three innings bridging Bobby O and Roger McD. How about Doug Sisk, despite the slump he sunk into in July of ’84 and seemed to come out of only intermittently? Sisk faced 312 batters in 1986 and gave up no home runs — no Met pitcher has come away from more encounters with batters in any season gopher-free. Hey, how about Randy Niemann, the personification of not the answer in lefty specializing? He did win his one start, in an August doubleheader, and Frank Cashen himself singled him out as a premier sprayer of champagne in Houston.

These were the days of the 24-man roster. Those were the 24 men the Mets suited up for the 1986 World Series. A dozen others played in the course of the year: George Foster, who went deep thirteen times before talking himself out of town; wunderkind hitter Dave Magadan, the All About Eve story of the September 17 division-clincher; Ed Lynch, the veteran righty who didn’t make it out of April; Bruce Berenyi, the once-prized acquisition who last pitched in July, then never again in the majors; Randy Myers, John Mitchell, and Terry Leach, pitchers whose biggest moments awaited a year or more down the road; Rick Anderson, the minor league lifer who capably soaked up handfuls of innings when the need arose; Barry Lyons, the catcher who gave way to Ed Hearn as Carter’s backup (reclaiming that role come 1987 and serving the Mets honorably into 1990); John Gibbons, the catcher who backed up Hearn when Carter briefly went down in August (serving the Mets currently as Carlos Mendoza’s bench coach); Stanley Jefferson, the next in what appeared a long line of fleet center fielders (serving New York later in the NYPD); and Tim Corcoran, the Keith Hernandez first base insurance policy, in case Keith served a yearlong suspension at the behest of Peter Ueberroth rather than take the deal the commissioner was offering after the Pittsburgh drug trials. Corcoran wound up playing in six games. Lynch, whose tenure dated back to the shadows of September 1980, pitched in only one before circumstances compelled him to be sent packing. In Jeff Pearlman’s The Bad Guys Won, good ol’ Ed likened it to “living with a family the whole year and getting thrown out of the house on Christmas Eve”.

They were all 1986 Mets, and we would gratefully thank each of them for being 1986 Mets if we bumped into any of them, but The 1986 Mets who manned the positions around Orosco (21 saves in the regular season, three wins in the NLCS) were exactly who you wanted to see out there as a world championship settled within our grasp late on Monday night, October 27. Carter crouching behind the plate. Hernandez, Backman, Santana, and Knight spread across the diamond. Wilson, Dykstra, and Strawberry covering the outfield. Good lord, that team really existed. Twenty-seven weeks had passed since that Monday night versus the Pirates in April. The Mets had won everything within reach for more than half-a-year. All that was left was three outs.

Ed Romero fouled to Keith Hernandez.

Wade Boggs bounced to Wally Backman.

Jesse Orosco struck out Marty Barrett.

Jesse Orosco’s glove flew into the air.

Gary Carter flew onto Jesse Orosco.

And that was that. The 1986 Mets had now won everything. They were world champions. Champions of the world. Winners of the World Series. World Series champions. Keep finding ways to say it. They are all accurate and wonderful.

This hadn’t happened for the Mets since 1969. I was six then. It was great, but I was six. This time I was twenty-three. I knew my baseball. I knew my Mets. Not as much as I would come to know baseball or the Mets, but more than enough to appreciate and retain every bit of what was going on around me and on television. As much as I expected this to happen, and as much as I had nurtured emotional muscle memory from ’69, I was newly delirious with joy, whooping and hugging and maybe having enough sense to shed a couple of tears. Nothing quite like this had ever happened to us or me. This had been the sui generis of Met seasons, capped off as it had to be capped off. “The dream has come true,” Bob Murphy summed the scene on the radio. Exactly, Murph. The dream worked. This was our dream. Winning the World Series is everything a baseball fan hopes for, and it had just happened. It was supposed to happen after 1984 and 1985 and waiting an interminable seventeen years overall. These were The 1986 Mets.

This hadn’t happened for the Mets since 1969. I was six then. It was great, but I was six. This time I was twenty-three. I knew my baseball. I knew my Mets. Not as much as I would come to know baseball or the Mets, but more than enough to appreciate and retain every bit of what was going on around me and on television. As much as I expected this to happen, and as much as I had nurtured emotional muscle memory from ’69, I was newly delirious with joy, whooping and hugging and maybe having enough sense to shed a couple of tears. Nothing quite like this had ever happened to us or me. This had been the sui generis of Met seasons, capped off as it had to be capped off. “The dream has come true,” Bob Murphy summed the scene on the radio. Exactly, Murph. The dream worked. This was our dream. Winning the World Series is everything a baseball fan hopes for, and it had just happened. It was supposed to happen after 1984 and 1985 and waiting an interminable seventeen years overall. These were The 1986 Mets.

Were? Try are. The present-tense extended for as long as they piled on one another on the field, and then sprayed bubbly one another in the clubhouse, and then rode (sans one notable pitcher) in their downtown caravan the next day, where I couldn’t see a whole lot but could feel everything. The championship designation remained intact after the ticker-tape was cleaned up. The 1986 Mets are still champions.

Even if they can’t help that it’s not 1986 anymore.

PART IV — STAYING THE 1986 METS BEYOND 1986

Jimmy Breslin was no longer a sportswriter by 1986, but he found the occasional Met angle for his Daily News column. One summer Sunday, he visited with Marc Gold of Staten Island. Much later, Gold would gain cachet as a Met superfan. His family business was the leading maker and marketer of horseradish, and Gold’s sponsored many a Met bobblehead day at Shea, then Citi Field. The players immortalized on the Gold’s mini-statues tended to get injured or fall apart in other ways, which wasn’t the fault of the horseradish or the proprietor.

Really, Marc was a pretty super fan from the get-go, keeping scrapbooks on everything the expansion club did and publishing is own newsletter, Met Maze. That was in ’62. In ’86, he was simply a businessman who recalled falling in love with the Mets the same year Breslin was making the most out of Casey Stengel’s quotes. Marc was 14 in 1962. The Mets were 40-120. His obsessiveness with them and their lousiness in general took a toll on his psyche. “Everybody made a joke of the Mets,” Breslin wrote, “but it wasn’t funny to a 14-year-old.” The 1962 Mets took precedence over his studies. His grades suffered. His future went in directions he hadn’t planned, and not necessarily for the better.

“Through all those years,” Breslin explained, “Marc, scarred in his youth, stayed away from baseball.” But then he got a look at Doc Gooden and started watching the Mets anew. He was back in the fold. “I deserve this!” he told Breslin. “I deserve this feeling I’m having.” Marc Gold spoke for all of us, even if we didn’t all go back to the beginning. I didn’t stay away from baseball between 1977 and 1983. I was the age Gold was in 1962 in 1977, the year the Mets traded Tom Seaver. “You can’t be 14 years old and have the team you root for lose three out of every four games they play. What a number that does on a poor kid,” Marc said. The 1977 Mets didn’t lose quite that often, but they chose to give away The Franchise rather than bobbleheads. What a number that does on a poor kid, too.

By 1986, any residual bemoaning was over ancient agony. Everything in the present was sunny and bright and double-digit games ahead of everybody else. Still, Gold cautioned, “I’m looking around me today. All these kids who root for the Mets, I want to see what this does to them 25 years from now. I want to see how they stand up under too much success.”

Turned out Marc Gold or anybody else didn’t have much to worry about vis-à-vis the warping of the values of the next iteration of the Youth of America. Young Mets fans didn’t have much of a chance to be spoiled by success. Mets fans who qualified as young adults didn’t, either. I went from 23 to 24 in 1987. I figured we’d keep winning. We sort of did for a few years, if you define winning as playing games and not losing as many as you win as a rule. The Mets’ records from 1987 through 1990 remained impressive, if not as impressive as 108-54: 92-70; 100-60; 87-75; 91-71. One of them was good enough for another division title. None of them resulted in another world championship.

Then came a half-dozen years without a single winning record (1991-1996), followed by five years with winning records (1997-2001) and two crackling postseason appearances facilitated by the implementation of the Wild Card (1999 and 2000), followed by three fallow years of losing (2002-2004), followed by four years (2005-2008) whose winning records rang rather hollow (one division title, one postseason series victory, each in 2006), followed by another six years of famine (2009-2014), the middle of which took us to 2011, which was 25 years after 1986, and I sensed no evidence of Gold’s concern coming to fruition. If Mets fans struggled to figuratively stand up, it wasn’t from too much success.

And so it has gone. Some good years here and there, especially lately, but nothing that provided precisely what 1986 provided. No world championship and only fleetingly a sense of rooting for an enterprise that was unbeatable. Those of us still standing still root for the descendants of 1986. And not a few of us take comfort that that the actual 1986 Mets continue to be The 1986 Mets.

In Spring Training of 1987, after a couple of contretemps various Mets wished to dismiss as no big thing, Dave Anderson in the Times suggested the club use the outer rim of Shea Stadium to advertise not “Baseball Like It Oughta Be” or “The Magic Is Back” or even (as it now read) “1986 World Champs,” but “We’ve Put That Behind Us.” Words to that effect were being uttered in St. Petersburg a little too frequently. I thought it also reflected the Mets’ policy of handling the immediate future. Was 1986 grand? It was the grandest. But it was no longer the present, therefore it was no longer where the Mets could look. Over the offseason, the club had traded Kevin Mitchell, said goodbye to Ray Knight, and altogether turned over nearly a quarter of the World Series roster. That was before Roger McDowell was diagnosed with a hernia that would keep him out for close to two months, and before, in the biggest blow of all, Doc tested positive for cocaine. The Mets who lined up to receive their rings on Opening Day at Shea weren’t unrecognizable from the Mets who embraced after Orosco tossed his glove the previous October, but when combined with their new teammates, they constituted a different bunch.

It was a bunch that had to put 1986 behind them. There’d be a lot of that as the 1980s wound down and the 1990s dawned. Some beloved familiar players aged out of the Mets’ plans. Some others weren’t content with limited roles and were traded for what was rationalized as the mutual good. Some seemed to management to not have the correct temperament to pursue the next world championship.

The next world championship has yet to present itself. Maybe the Mets did have to shed the immediate past and refocus with other types of players. Or maybe what had worked in 1986 should have been trusted a little longer. After a while, it didn’t matter. Everybody from 1986 wasn’t going to stay forever as active players. Yet before time could gracefully take its course, the Mets as a business seemed to develop an allergy about acknowledging 1986 as a blueprint for future success and shunned The 1986 Mets as attitudinal role models for their young players. When you reread The Worst Team Money Could Buy by Bob Klapisch and John Harper, the salaciousness surrounding the 1992 Mets isn’t the shocker. It’s how badly the people who ran the Mets by 1992 wanted to forget about 1986, or at least the character that permeated 1986.

“Cashen and the others,” the authors wrote, “didn’t realize or care that Knight and Mitchell, both legitimate tough guys, had been the muscle behind the Mets’ strut. But that was just the beginning.” Vocal Mets became disappeared Mets, including Davey Johnson, the most successful skipper the Mets ever had, dismissed in May of 1990 as if he was just another manager. “Owner Fred Wilpon, in particular, wanted to homogenize his ballclub […] and began to assert more influence on the baseball decisions as the Mets’ glory faded.” You’d see a clip of a ball bouncing through an opposing first baseman’s legs played on DiamondVision during a rain delay, maybe. You wouldn’t see much other evidence of 1986 as the 1990s wore on.

That amnesia couldn’t last forever, because 1986 was destined to live forever. Some players came back as coaches at the major and minor league level or as Spring Training instructors. They didn’t always last in those roles, but they were at least given a shot. Old Timers Day went away after 1994 (not to return until 2022), but when the Mets did host the occasional event spotlighting their history from 2000 onward, 1986 Mets were in bountiful attendance, and usually the mostly warmly received of any alumni en masse. A couple of 1986 Mets became club broadcasters and got very good and very popular doing it. The twentieth-anniversary celebration of The 1986 Mets in 2006, by which time they were all retired, couldn’t have been more electric. The thirtieth-anniversary bash in 2016 was just as much of a hoot. Not every 1986 Met has shown up for every get-together in Flushing these past two decades, but everybody seems to have made his peace with an organization that clearly values the connection.

That amnesia couldn’t last forever, because 1986 was destined to live forever. Some players came back as coaches at the major and minor league level or as Spring Training instructors. They didn’t always last in those roles, but they were at least given a shot. Old Timers Day went away after 1994 (not to return until 2022), but when the Mets did host the occasional event spotlighting their history from 2000 onward, 1986 Mets were in bountiful attendance, and usually the mostly warmly received of any alumni en masse. A couple of 1986 Mets became club broadcasters and got very good and very popular doing it. The twentieth-anniversary celebration of The 1986 Mets in 2006, by which time they were all retired, couldn’t have been more electric. The thirtieth-anniversary bash in 2016 was just as much of a hoot. Not every 1986 Met has shown up for every get-together in Flushing these past two decades, but everybody seems to have made his peace with an organization that clearly values the connection.

What wasn’t intended to live forever was 1986’s status as the most recent world championship season the Mets have had. If you lived through and loved the 1986 season, you will always love being reminded of it. Yet you’re not thrilled being reminded, however implicitly, that its signature accomplishment has not been matched. It hits me in little ways. For example, every October MLB Network runs a promotional montage featuring its band of former players turned analysts achieving something in a postseason. The footage of Ron Darling pitching in the 1986 World Series is clearly grainier than everybody else’s clips. Yeah, 1986! My god, that was so long ago. Nevertheless, I stood and applauded at the twentieth-anniversary reunion as if twenty years wasn’t more than twenty minutes ago, same as I did at the thirtieth-anniversary reunion, same as I did for every 1986 Met who showed up to commemorate the franchise’s sixtieth anniversary, same as I did when a slew of those guys showed up to support Keith, Doc, and Darryl when their numbers were retired. Blessedly, almost all of The 1986 Mets are still around, something you wouldn’t have bet on had you known the stories that later came out about their off-field exploits. I miss Gary Carter, but I’m grateful each of his 1986 teammates is available to tell us again what a good man he was.

What wasn’t intended to live forever was 1986’s status as the most recent world championship season the Mets have had. If you lived through and loved the 1986 season, you will always love being reminded of it. Yet you’re not thrilled being reminded, however implicitly, that its signature accomplishment has not been matched. It hits me in little ways. For example, every October MLB Network runs a promotional montage featuring its band of former players turned analysts achieving something in a postseason. The footage of Ron Darling pitching in the 1986 World Series is clearly grainier than everybody else’s clips. Yeah, 1986! My god, that was so long ago. Nevertheless, I stood and applauded at the twentieth-anniversary reunion as if twenty years wasn’t more than twenty minutes ago, same as I did at the thirtieth-anniversary reunion, same as I did for every 1986 Met who showed up to commemorate the franchise’s sixtieth anniversary, same as I did when a slew of those guys showed up to support Keith, Doc, and Darryl when their numbers were retired. Blessedly, almost all of The 1986 Mets are still around, something you wouldn’t have bet on had you known the stories that later came out about their off-field exploits. I miss Gary Carter, but I’m grateful each of his 1986 teammates is available to tell us again what a good man he was.

A few of them have experienced some very public issues (to put it kindly), but as a unit, The 1986 Mets have demonstrated incredible staying power. This is a group that will always be asked about that pitch or that swing or that little roller, and nearly four decades later, they appear content to revisit that slice of their life. All former ballplayers carry such a burden, and maybe it’s hardly a burden. When was the last time anybody asked a normal person to relive some day at the office from more than half-a-lifetime ago because what that person did way back when continues to make other people happy? Still, they have to be The 1986 Mets in a way I don’t think the 1969 Mets have to fill their own exalted role. Oh, the Shamskys and Swobodas are asked about their year in the sun every single day they are recognized, but the 1969 Mets aren’t “the most recent,” and there isn’t that lingering sense of there should have been something more from them and their colleagues when they come up in conversation. Besides, no matter how good the 1969 Mets really were (100 wins, nothing to sneeze at), they are perceived as the wonder of wonders, miracle of miracles, whereas the talent that constituted the 1986 Mets seems too good to be confined to one year of winning everything. They won “only once,” as if one team in one season could have won more, let alone with more élan or authority. Perhaps the era for which 1986 is convenient shorthand should have yielded another trophy, but once it stopped being 1986, those specific Mets couldn’t put anything else in the win column. The 1986 Mets were done playing ball the moment Orosco struck out Barrett.

A few of them have experienced some very public issues (to put it kindly), but as a unit, The 1986 Mets have demonstrated incredible staying power. This is a group that will always be asked about that pitch or that swing or that little roller, and nearly four decades later, they appear content to revisit that slice of their life. All former ballplayers carry such a burden, and maybe it’s hardly a burden. When was the last time anybody asked a normal person to relive some day at the office from more than half-a-lifetime ago because what that person did way back when continues to make other people happy? Still, they have to be The 1986 Mets in a way I don’t think the 1969 Mets have to fill their own exalted role. Oh, the Shamskys and Swobodas are asked about their year in the sun every single day they are recognized, but the 1969 Mets aren’t “the most recent,” and there isn’t that lingering sense of there should have been something more from them and their colleagues when they come up in conversation. Besides, no matter how good the 1969 Mets really were (100 wins, nothing to sneeze at), they are perceived as the wonder of wonders, miracle of miracles, whereas the talent that constituted the 1986 Mets seems too good to be confined to one year of winning everything. They won “only once,” as if one team in one season could have won more, let alone with more élan or authority. Perhaps the era for which 1986 is convenient shorthand should have yielded another trophy, but once it stopped being 1986, those specific Mets couldn’t put anything else in the win column. The 1986 Mets were done playing ball the moment Orosco struck out Barrett.

All those wins across six pulsating months. All that heartstopping melodrama in October. All that confetti that deluged Lower Manhattan. They won enough in their year to last us nearly forty years. It’s up to another Mets team to relieve them of the “most recent” onus. The 1986 team was built to win a world championship in 1986. It wasn’t built to be the last Mets team to win a world championship, whether you qualify “last” with a “since” or not. Their title, like 1969’s did until 1986, was supposed to serve as an aspirational example before the next the next one(s) came along. We’re still aspiring for a third Mets team to join the both of them. And we’re still using “since 1986” in our sentences, which I’d definitely like to stop. No time like the present, right?

I have confidence in the current Met club. I’ve had confidence in other Met clubs, too. Yet only one Met club ever has had me counting the minutes eight hours to first pitch.

PREVIOUS ‘MY FAVORITE SEASONS’ INSTALLMENTS

Nos. 55-44: Lousy Seasons, Redeeming Features

Nos. 43-34: Lookin’ for the Lights (That Silver Lining)

Nos. 33-23: In the Middling Years

Nos. 22-21: Affection in Anonymity

No. 20: No Shirt, Sherlock

No. 19: Not So Heavy Next Time

No. 18: Honorably Discharged

No. 17: Taken Down in Paradise City

No. 16: Thin Degree of Separation

No. 15: We Good?

No. 14: This Thing Is On

No. 13½: Making New History

No. 13: One of Those Teams

No. 12: (Weird) Dream Season

No. 11: Hold On for One More Year

No. 10: Retrospectively Happy Days

No. 9: The September of My Youth

No. 8: First Taste

Nos. 7-5: Three of a Kind

No. 4: Pound for Pound

Wow, what a wrap up. My favorite year when I was 35. And my career highlight to boot. I can’t write like you but I make a hell of a video. Enjoy:) https://youtu.be/ISTOWf5GWuc

Thanks for posting this, very enjoyable, and some great backstory.

I turned 24 in ’86 and was working part-time while going to Grad School at SUNY Albany and from a distance of 180 miles was able to really follow that season and catch quite a few games. I’ve thought sometimes that this was the last time my being a naive fan paid off. By naive I mean feeling like things would turn out right for your team no matter what, they were destined to win it all, it would turn out OK. Those were the days when I watched the Knicks being down 20 with 2 minutes left and mentally constructed how they could come back, or when my baseball team trailed by 2 runs with two outs nobody on in the final inning of what could be their last game of the season and they would still win. My Bob Uecker period. The Mets didn’t kill it BTW – I felt the same way in 1988 and was disappointed. It was because of the 90’s Knicks that I became what I am now, a person who half expects Juan Soto to have a season-ending injury at some point by June 1.

I watched games 6 and 7 from the TV Lounge at Albany while cutting class. From the absolutely packed SRO I wasn’t alone. We all have our own set of experiences with it but in my entire life that was the greatest group emotion experience I’ve ever had for a sporting event – this happens when you cheer for NY teams but live elsewhere; seeing the Knicks eliminate the Pacers at Market Square Arena in Indiana is certainly satisfying in its way (the way I feel at seeing thousands of devastated people at the end of a game does not make me proud as a person) but not like when you’re surrounded by like-minded fans. And personally I knew we’d win game 6 no matter how bleak things looked and game 7 when we fell behind. I was that annoying-as-hell guy looking at the person sitting next to me almost in tears saying, “We’re still gonna win this.”

And we did.

1986 can be difficult to describe, as there’s just no other Mets season to compare it to. They went into it fully expecting to win it all, and that’s not typical. Then, they curtain called, brawled, and steam rolled through the National League to a degree where the whole regular season was like one big Mets party. There’s never been a season where the Mets were a division lock by mid-July. Oh, it was just glorious, no tension, worry or doubt at all, at any point.

Then, in October, it was ALL tension, worry, and doubt. Relentless, all-consuming anxiety. Losing the NLCS or the WS in 1986 would have been crushing to a point where it would have reshaped the entire fan base permanently. They COULDN’T lose. And, almost as if to prove it, they took it to the limit. It was all so surreal. One unbelievable thing after another, culminating in the most outrageous one of them all, followed by ANOTHER thrilling comeback AND a full-fledged victory lap to close it out. I mean, the freaking Mets won the freaking World Series. It still seems unreal sometimes.

Maybe someday, it might be matched (although that’s a tall, tall order) but 1986 will never be topped. It was the perfect confluence of everything. As the (sigh) years zoom by, I look back on it with awe, and an appreciation of just how astonishing it really was.

Fantastic! Along similar lines to counting the hours down to season opener, today is my MetsMas Eve. Cos tomorrow.. is Metsmas DAY! Happy MetsMas everybody, I’m sure we’ll get some great gifts

I never was much of a boxing fan, but Ray Knight and Eric Davis had an interesting match.

That was a classic game. A huge brawl, Dave Parker dropping the last out, Gary Carter playing third, Keith playing out of his mind, Orosco and McDowell playing RF…AND they won.

And I remember John Franco slamming the ball into the ground in frustration after Parker dropped that pop fly. That wasn’t pretty.