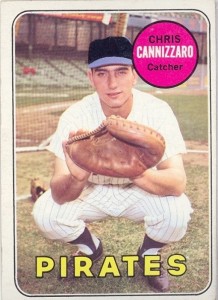

This card was brought to my attention a couple of months ago and I can’t get it out of my head. It’s a veritable diner placemat that urges you to find all the things that are wrong with it while you tear open another package of melba toast and wait for your cup of chicken consomme with matzoh ball and/or noodles to arrive.

Never mind that the two-toned black and vaguely lavender cap seems to be missing a Colorado Rockies logo from the distant future. Never mind that the next time the Pittsburgh Pirates sport light blue pinstripes will be the first time. Never mind your instinct to inform the photo’s subject that, “YO! HOME PLATE’S OVER THERE!” These reality-warping techniques were pretty standard stuff for Topps in its monopolistic heyday, which 1969 — the year of issue for this card — was smack-dab in the heart of.

What blows my mind, to invoke 1969 patois, is that the catcher in the middle of the card, Original Met Chris Cannizzaro, is squatting in the Polo Grounds. To squat in the Polo Grounds in 1969, you’d have to take the measure of the New York City Housing Authority Police Department, because they would probably have thrown you out, much the way Chris Cannizzaro once threw out thieving baserunners on the same plot of land.

As I don’t think I have to tell you, the Polo Grounds, home of the first two Mets teams, was the domicile of non-baseball players by 1969. The Mets vacated their temporary digs at the end of the 1963 season and moved to Queens. The city, as it had planned to do before Bill Shea and Branch Rickey conspired to invent a new National League ballclub that needed an old National League ballfield, finished tearing down the stadium that sat on Eighth Avenue between 155th and 157th Streets on April 10, 1964, one week before Shea Stadium opened. A housing project went up in the Polo Grounds’ place. It retained the Polo Grounds name, perhaps for reasons related to sentiment or familiarity, perhaps so when New York Giants romanticists like myself would trek uptown to find it, we wouldn’t get too lost.

The Polo Grounds Towers opened as public housing on June 30, 1968. The Mets didn’t live there anymore. Cannizzaro didn’t get his mail there anymore, either. According to Baseball-Reference, Chris was spending most of his 1968 as a Columbus Jet, grooming the Triple-A pitching staff of the Pittsburgh Pirates. After rediscovering his mojo in Ohio, the catcher who hadn’t been a major leaguer since late 1965 (he caught part of the Rob Gardner/Chris Short 18-inning 0-0 tie on October 2 and the Closing Day doubleheader nightcap that game’s curfew necessitated on October 3) was reportedly happy to be recalled to the Bucs in August. On September 14 and 15, Chris donned the so-called tools of ignorance, got behind the plate and caught a pair of games in New York…at Shea Stadium, not the Polo Grounds. To do so at the Polo Grounds would have been bad form, as throwing the ball back to the mound might have entailed hitting some lady bringing home her groceries.

Brooklyn-based Topps seemed to shoot most of its in-season National League photos in those days at Shea. Chris Cannizzaro was available for framing as a 1969 Pirate in September of 1968. Otherwise, it would use pictures captured during Spring Training. Chris, I’m pretty sure, attended the rites of spring every year he was bouncing among different organizations and trying to make a big league club. Topps occasionally dipped into its archives and plucked out a photo that had clearly been taken a couple of years earlier. For example, you can’t miss the NEW YORK WORLD’S FAIR patch on Al Jackson’s 1969 card. The World’s Fair closed in 1965 (a season when Chris played 57 games at Shea), but at least we know the stadium it was built next to was still standing in 1969.

The Polo Grounds wasn’t. Yet there is Mr. Cannizzaro, on Card No. 131, quite clearly ready to put down fingers in a stadium that was no more. He’s dressed as a Met. He’s identified as a Pirate. He’s airbrushed as a proto-Blake Street Bomber. And he’s in a place where there’s been NO GAME TODAY for more than five years.

Some call it spooky. If I stumbled upon this card at a tender age, it probably would have frightened me. Anything that wasn’t incredibly up-to-date seemed askew to me when I was a kid. But now, knowing the Polo Grounds lived on an Original Met’s card deep into the Shea Stadium era strikes me as nothing short of Amazin’. It could be construed as good luck, too, as Chris caught a significant break toward the end of 1969’s Spring Training. Just as kids were opening their wax packs and being convinced Cannizzaro was, contrary to almost all graphic evidence, a Pirate, Pittsburgh traded him to that new team in San Diego. As a retread Pirate pushing 31, he wasn’t likely to see much action behind budding star Manny Sanguillen even if he did make the Bucs out of Bradenton. But as an Original Padre, Chris Cannizzaro saw the most playing time (134 games) of his long and heretofore, shall we say, underdistinguished career.

In 1969, Chris Cannizzaro was named to the National League All-Star team. Granted, it was one of those “we gotta pick a Padre” choices, with Chris batting .245 and collecting 2 home runs and 23 runs batted in by the All-Star break, but it was a long-in-coming response to those who doubted his credentials as a Met, including his first manager. As David Bagdade recounted in A Year In Mudville, Casey Stengel referred to Cannizzaro — a name he unfailingly pronounced as “Canzoneri” — as “the only defensive catcher in baseball that can’t catch”. And Casey was just getting started in his appraisal:

“The pitcher throws. Wild pitch. Throws again. Passed ball. Throws again. The ball drops out of the glove. And all the time I am dizzy on account of these runners running around in circles on me and so forth.”

This particular scouting report, whatever its accuracy (Chris could throw — he nailed 20 of 36 runners who tried to steal on him in 1962), was no doubt historic. Casey ranted on until he found himself wondering aloud, “Can’t anybody play this here game?” Jimmy Breslin came along directly and twisted the Stengelese ever so slightly and invented the signature question that has stayed with the Original Mets ever since: Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game?

On the 1969 Padres, relative to teammates who were building a 52-110 record that looked good only when compared to the Mets’ 40-120 of seven years earlier, Chris could. He was the All-Star. He was third among all N.L. receivers in Caught Stealing, halting 41 runners who had ideas about taking bases that didn’t belong to them (Jerry Grote was fourth, with 40). True, he was also third in most bases stolen against, with 58, and he wound up the season batting .220, but on a 52-110 enterprise, Cannizzaro could squat proudly as someone who wasn’t necessarily one of the primary culprits.

Chris hung on as a Padre, a Cub, a Dodger and a Padre again through 1974, lasting as long among Original Mets as anyone. His final MLB game came on September 28, 1974, more than two months after Jim Hickman was released by the Cardinals and the same day Bob L. Miller threw his last pitch as a Recidivist Met. It was their (and, though he wasn’t Original, Ed Kranepool’s) longevity that helped reduce my personal fright factor where “ancient” Mets history was concerned. When I discovered the Mets in 1969, I couldn’t grasp the idea that they existed in such a dismal state, standings-wise, in those years when I was too young to have witnessed them. Yet with Cannizzaro, Hickman and righty Bob Miller still on the scene, even as opponents, Bob Murphy, Lindsey Nelson and Ralph Kiner were compelled to explore each player’s backstory. Still couldn’t quite reckon that players from way back then, just before I was born, could have been members of my team at its very beginning and still be active, but it began to sink in bit by bit. Nowadays I write books that in part celebrate that portion of my team’s history.

Before a very nice guy named Paul posted anachronistic Cannizzaro from 1969 on Crane Pool Forum in September and got me thinking about him, there was another reason the man who caught in the company of Choo Choo Coleman, Sammy Taylor, Joe Pignatano, Hobie Landrith, Harry Chiti and the recently deceased Joe Ginsberg in 1962 had been rattling around in my head. It came via a story from two Mays ago, just after the killing of Osama bin Laden. As Spencer Fordin reported for mlb.com, a Staten Island boy who wasn’t yet a year old when he lost his firefighter dad on 9/11 threw out the first pitch of the Mets-Dodgers game at Citi Field on May 6, 2011. He was ten by then and a completely rabid Mets fan. His name?

Christopher Cannizzaro. No relation by blood or marriage to the catcher who will turn 75 in 2013. It was more visceral than that. Both his parents, Brian and Jackie, were huge Mets fans and if their last name was Cannizzaro, then what else were they going to name their kid, especially one who was born during the 2000 Subway Series? Brian went so far as to place a Chris Cannizzaro card in his son’s incubator when he was born. Christopher’s route to fandom was just a matter of time and destiny from there.

The card that accompanied the infant in his first days probably wasn’t the 1969 Topps with the illogically lingering image of the Polo Grounds, given that the Original Met was labeled a Pirate in that edition and one would guess Brian preferred to introduce Christopher to Chris in non-airbrushed Met form. But that’s OK. Spirits live on in all sorts of ways.

Image courtesy of Wrigley Wax.

Leave it to a Mets fan to take a random Mets name like “Chris Cannizzaro” and spin a story like this out of it. Just brilliant, well done!

Yep, this is why I’m still reading a Mets Blog in late November.

And thanks for the memory jog. Wow, I actually do remember being happy to see the long-lost Chris Cannizzaro show up out of the blue (no pun intended) on TV in one of those two September 1968 games.

Good read on a blustery Novemeber Sunday, Greg.

I did recall hearing about young Master Canizzaro in 2011. I never did hear or read whether he was, or wasn’t, related to the 1962 Met Chris Canizzaro. Until now. The more eye straining Canizzaro card is, however, his 1975 Topps card, where the catcher’s Padre uniform is airbrushed in day-glo yellows and browns.

I hear you when it comes to being a very young brand new Mets fan and learning that people on other teams like Tommy Davis and Ron Hunt and heaven forbid Jim Hickman (OMG, he was playing for Durocher’s Cubs) had been Mets. How could that be? The Mets, I figured, were just these guys who were on the team at that time, nobody else could have belonged to that fraternity. Took some time to wrap my head around it.

Hi Greg,

Nice story as always.

My memory of Chris comes from the fact that despte only playing 60 games with less than 200 at bats in 1964, the Mets Yearbook (1965 edition) heralding him as having become a .300 hitter when he stopped swinging for the fences – we all knew at the time Chris had yet to hit one out in the majors. Yes, Chris hit .311 that season and along with the Dick Stuart of backstops, Jesse Gonder and Hawk Taylor, the Mets seemed to have one of the better offensive catching units in the game.

Of course, all that changed in 1965 when Chris couldn’t even hit .190, let alone .200. He was so inept at the bat that he hadn’t driven in a run for not quite yet the first half of the season though he was played in a lot more games. Finally, toward the end of June in a game at Candlestick Park, Chris finally drove in his first run of the season, which was, actually, the only run the Mets scored in a 2-1.

Why remember that so well? For part of the next day’s headline in the Daily News was: “CANNIZARO DRIVES IN RUN”.