In the beginning, the Mets didn’t have to play youngsters. The Mets were a youngster, a toddler, the bouncing baby of the National League basement. No matter who they featured, the thinking went, they were going to be clumsy, so they might as well be familiar. Hence the 1962 Mets’ early reliance on daily lineups of veterans who’d been through the senior circuit wars of the 1950s: Hodges, Zimmer, Thomas, Bell, Ashburn, Mantilla, Neal, Landrith. Everybody there had played this game…and seen better days in it. “All the memories were in the past tense,” George Vecsey wrote, “and most of the talent was that way, too.”

A year later, it was the beginning of a different story, with eternal spring chicken Casey Stengel touting his Youth of America. Ed Kranepool had debuted the previous September at just seventeen, if you know what I mean. Ol’ Case saw him standing there in St. Pete and invoked a previous phenom who got his feet wet at the Polo Grounds: “Who says you can’t make it when you’re eighteen? Ott made it when he was eighteen.” Mel Ott also played until he was 38 and hit 511 home runs. While Eddie dealt with perfectly reasonable comparisons, it was Ron Hunt, 22, who was poised to become the promising newcomer of 1963. Hunt batted .272, took 13 pitches to his person, finished behind Pete Rose for NL Rookie of the Year honors and was about to be the baby face of the two-year-old franchise as it took its act from Manhattan to Queens in 1964.

There’d be push and pull between the young and the old (baseball old, that is) as the 1960s progressed and the Mets intermittently strove to field promise on a daily basis. As 1965 wound down, and Wes Westrum assumed the managerial reins from the reluctantly retired Stengel, he leaned on not just Kranepool and Hunt — each an All-Star already — but rookies named Ron Swoboda (21), Bud Harrelson (21) and Cleon Jones (23). “We’ve looked at old players for four years,” Westrum reasoned, with another triple-digit sum of defeats staring him in the mirror. “We’ve got nothing to lose giving the kids a chance.”

Come 1966, the Mets would rise above tenth place and lose fewer than a hundred games for the first time in their history. It was about time. It was also about experience. Westrum’s key kids included Roy McMillan, 37; Ken Boyer, 35; Ed Bressoud, 34; and Chuck Hiller, 31. On the other hand, Jerry Grote, the new catcher, was all of 23, and Kranepool, 21, was still getting the hang of voting. Grote and Kranepool, like Swoboda, Jones and Harrelson, would be sticking at Shea Stadium beyond 1966, while those aforementioned veterans would all be gone before 1968.

The same fate that befell Boyer, et al, however, awaited Hunt, who sure appeared destined to star at Shea for years to come. Ron was traded with Jim Hickman to Los Angeles for Tommy Davis. Davis, a two-time batting champ, wasn’t exactly ancient when he took over left field at Shea in 1967, but he had miles on him; like Hunt, an injury struck him in 1965 and, like Hunt, his career never looked quite the same. After one solid year for the tenth-place Mets, Tommy, 28, was swapped to the White Sox for a Tommie — Agee, that is — plus Al Weis. Agee, 25, had very recently been the AL Rookie of the Year.

You never know how the demographics will coalesce on a given diamond or in a given era. The story of 1969, which nobody knew was having its preface penciled in as early as 1962 when Master Melvin’s successor Steady Eddie was taking his first swings, is one of kids coming together to take a division, a league and a world by storm. There’s no overlooking the mentorship and big hits provided by the veterans — Weis, Ed Charles and Donn Clendenon all effectively platooned for Gil Hodges from the other side of 30 — but we revel in the image of the Youth of America in full bloom. The young pitchers obviously mattered momentously, but at the core of the so-called miracle were those position players who were once prospects and who were now becoming champions. They all took the field together on the afternoon of October 16, 1969, and all ran for their lives from a grateful throng a couple of hours later.

Ed—24

Tommie—27

Bud—25

Cleon—27

Ron—25

Jerry—27

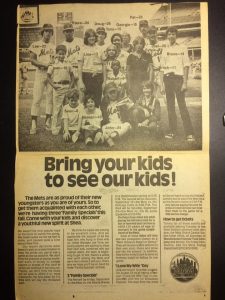

Even when the blossoming is slow to reveal itself, youngsters growing into winners is an ideal we all hope on. In the Mets’ darkest days, the late summer of 1977, the team’s marketing department, such as it was, went there. It went to the kids. It went to Our Kids, as in the Mets begging parents across the Metropolitan Area to “Bring your kids to see our kids!” The unironic newspaper ad copy wanted us to forget that so many of our former kids were no longer our vets, so it preached promise.

The Mets are as proud of their new youngsters as you are of yours. So to get them acquainted with each other, we’re having three “Family Specials” this fall. Come with your kids and discover a youthful new spirit at Shea.

The you gotta be kidding pitch has M. Donald Grant’s nefarious fingerprints all over it, as the ad attempts to explain away “trades we felt we had to make” in the name of keeping prices down. In addition to losing ballgames and fans at a rapid clip in 1977, the Mets were also lagging in prescience: “We don’t think the practice of paying exorbitant sums of money to certain players in excess of that paid to others will continue in the long run.”

Yeah, good luck with that, Don.

The brighter point of the advertising campaign was to claim “the trades are proving to be excellent ones […] under Manager Joe Torre, our young players are starting to show their stuff and, combined with our veteran talent, the team is beginning to gel.” The best of the veteran talent had been shipped off on June 15, but the ad preferred you focus on the youngsters who composed the big picture — literally the big picture at the top of the ad, an intermingling of young Mets and younger Mets fans. The bigger kids were helpfully identified by first name and age.

Lee—22

Steve—24

Doug—26

Pat—25

Joel—25

John—24

Also pictured: Lisa, Tony, Georgie, Bruce, Ivan, Cindy, Robert, Sylvia, Brock, Sean and Noreen, who ranged from six to fifteen. Those were “your kids,” the ones adults buying a full-priced box or reserved seat were invited to bring along for free to those Family Specials. The attraction was “Our Kids”: Mazzilli, Henderson, Flynn, Zachry, Youngblood and Stearns, five of them getting a chance to play every day and one tasked with pitching every fifth day. Unnoted in the invitation, but certainly implicit, was a chance to get another glimpse of Ed Kranepool, by then a Met forever, yet only 32 in people years.

Did anybody actually bring their kids to see the Mets’ kids because the Mets strongly suggested it would make for a fabulous family outing? According to Baseball-Reference, attendance did not noticeably tick up on the first two promotional dates, while the third was rained out. Attendance kept plummeting in 1978 and 1979, two more years when the one thing the Mets couldn’t advertise was winning baseball. By the time the Mets got good again, none of Our Kids from 1977 had much of anything directly to do with it.But there would be new kids. There usually are. Come 1984, the kids dotting Met lineups would be named Mookie and Hubie and Wally and Darryl (not to mention a few kid pitchers of note). More such kids would be coming soon, as would be a torrent of paying customers impressed not by slogans and specials but hits and runs. These kids of the early ’80s would blend with some imported elders of renown — including that once-young Mazzilli fellow, reborn in grizzled veteran form for a second Flushing go-round — and the 1986 Mets would create history.

Over the next thirty-odd years, the Mets would attempt to re-create not only that kind of championship result, but that kind of incredible chemistry. The push and pull of young and old continued apace. Sometimes all ages meshed. Other times every Met in sight seemed to be born too soon or have matured too late. With the exception of occasional outliers — Jose Reyes came up at 19 in 2003; Julio Franco hung around until he was 48 in 2007 — you didn’t necessarily notice whether your Mets of any particular year seemed particularly young or especially old.

In 2019, you noticed.

In 2019, the Mets had veterans. In 2019, the Mets had pitching. But mostly in 2019, the Mets had a youthful core throughout the infield and within the outfield. That core defined who the Mets were as a team and what we as Mets fans felt about the team. This is why Faith and Fear in Flushing is presenting its 2019 Nikon Camera Mets Player of the Year award — dedicated annually to the entity or concept that best symbolizes, illustrates or transcends the year in Metsdom — to the latest edition of Our Kids.

Pete—24

Amed—23

J.D. — 26

Jeff—27

Michael—26

Dom—24

Brandon—26

Together, this cluster of seven position players generated an energy and emitted an aura that made rooting for the Mets fun for fans of all ages.

One great big clusterfun.

Funny thing is I don’t think we even realized we are were at the tipping point of a youth movement as 2019 approached. Sure, the game was getting younger and perhaps cheaper from the perspective of clever front offices everywhere; youth was definitely being served, service time manipulation notwithstanding. And sure, our talent pool included three former No. 1 picks; a former prospect who had only a couple of years earlier landed in the upper echelon of everybody’s projections; a slugger who led the minor leagues in homers the year before; an infielder who batted .329 in an extended audition upon his late-July 2018 callup; and a castoff from an organization that mostly developed studs. With hindsight, the pieces were there. It just hadn’t occurred to us to put them together in advance. It probably hadn’t occurred to the Mets, either.

By the end of the season, they were the Mets more than any Mets were. Granted, those seven Met kids — one more than the Bradys, one fewer than the Bradfords — had help throwing their party. Certified veterans Frazier, Cano and Ramos. Pitchers-in-their-prime deGrom, Wheeler and Matz. Journeyman cameoists Gomez, Altherr and another Davis. That’s how teams that win more than they lose work. Yet over 58 seasons of Mets baseball, I’d be hard-pressed to name another reasonably successful edition whose essence was so vastly defined by its youthful core of position players. 1969 had Seaver and Koosman. 1986 had Hernandez and Carter. 1999 and 2000 had more guys who’d been around than hadn’t. 2006 and 2015, too. All of those guys from all of those years were wonderful. The guys we’re talking about from 2019 were different. Wonderful, but different in composition and as a critical mass.

It would be a blast to report that the kids who elevated our mood from the middle of July to the end of September had a 1969-style ending to their season, but we know they didn’t reach October. It would be most photogenic had they all been gathered together and preserved for posterity the way the wishful-thinking class of ’77 had been, yet the seven of them didn’t even congregate in the same box score after May 16. The closest we had to a “Bring your kids…” treatment was a commercial run on SNY for Beanie Night in September. Pete Alonso, Amed Rosario, J.D. Davis, Jeff McNeil and Michael Conforto each wore the pom-pommed winter hat the club was giving away, their smiling faces popping up in boxes like they were Mike Nesmith and the rest of the Monkees, monkeying around like it was 1966. Chances are the Mets kids needed to have the retro concept explained to them (The Monkees having completed its last revival on MTV well before any of these players were born), but whoever came up with the concept certainly captured the zeitgeist of this moment in Met time.

Except Brandon Nimmo and Dom Smith weren’t included. Nimmo had been injured most of the summer and Smith was on the IL. Players who are hurt apparently can’t sell hats. By the time Smith was activated and putting a signature on the season’s conclusion with his walkoff home run of September 29, McNeil was sidelined with a fractured right wrist. Mickey Callaway or whoever dictated lineups to the former manager never thought to cooperate, either, as these seven Mets didn’t once trot out to their positions to start a game. Blame lefty-righty matchups and the stubborn incumbency of a couple of vets who were slow to cede claims to their spots on the field.

Yet when we see 2019 in our memories, once our memories enter the serious past-tense stage, we will see these kids together. We will remember their assorted individual accomplishments, natch, but we will feel what they brought to the Mets. The zeitgeist and zest. The vim and vigor. The exuberance that, like the exuberant, never quit. Shirts ripped from one another in exultation. Repeated declarations of resilience embodied in the actions of the inevitably half-clad resilient. A guy on a scooter racing out to embrace a guy called Scooter. Acronyms updated and hashtagged. A Polar Bear, a Solar Bear and a Squirrel. Second halves that were more than twice as good as their predecessors. Two of the young men officially named All-Stars at midseason; two others named theoretical All-Stars for what they did the rest of the season. Shouts about “that New York swagger” and “that New York attitude” in the wake of another New York win. Youth too young to understand their chances to contend had dwindled to practically nil, while experienced old heads watching from a distance drew overly hasty conclusions that it was not too soon to call it a year. Our Kids were impatient to win, yet demonstrated more patience than we did that they eventually would.

As fans we don’t proof at the door. Did we mind, even amid the “don’t trust anybody over thirty” mindset of 1969, that Weis, Clendenon and Charles were older and established when they arrived among us? Did we care in 1999 that Ventura, Piazza and Olerud, to name three, had all come from elsewhere and were each over thirty when they were joined by Rickey Henderson and Orel Hershiser — 40+ California legends — to put us over the top and get us into the playoffs? Is McNeil, 27, necessarily a kid? Is Conforto, who played in the 2015 World Series, not already a veteran? Wasn’t Davis technically a member of those paragons of virtue, the 2017 Houston Astros, before any of us took full note of what a gift those recent world champions had sent us?

Sometimes not everything can be dated via precise chronology or measured by tenure. Sometimes we just know and we can be comfortable fitting who see fit in those boxes we create. Yes, McNeil, an All-Star in his first full season in the bigs, is one of Our Kids. Yes, Conforto, an All-Star in 2017 like Kranepool was an All-Star in 1965 — because the Mets had to have somebody designated as such — was still coming along as 2019 got going. Yes, Davis, a bit player on a potential dynasty maybe too smart to comprehend all its assets, had to come to New York from Houston to let his freak swag fly…as did Grote 53 years before.

Alonso we had a clue would hit ’em out of the park, though we had no idea he’d hit more than anybody else, wind up speaking on behalf of everybody quite often and winning everything a rookie can win. Rosario we were thinking would have to move to center, but that was before he truly got the hang of short and hit nearly 60 points better in the second half than he did in the first. Nimmo reminded us what the happiest man in baseball looked like when he returned in September, whether it was sprinting to first on walks or doing sponsored self-parody; seriously, check out Brandon’s interpretation of Pete’s #LFGM. And Smith, whose stock plunged the minute his alarm didn’t go off to start Spring Training the year before, couldn’t have been more alert to his opportunity when this year ended (he also outlasted the manager who fined him for sleeping late).

What a difference a spring, a summer and a hint of autumn make. Dom, referring to what made these kids these kids and this team this team the last time this team would be exactly this team, told Steve Gelbs, “This group from Spring Training, we grinded together, we vibed in the locker room and we had a lot of fun. We wanted to change the culture here, we wanted to have fun and we wanted to win ballgames.”

That he said it drenched from a Gatorade bath only lent credence to Dom’s words.

Yes, this was our youthful core. Yes, they were a delight to take in as a unit. Yes, the method by which they evinced enthusiasm for one another could come off as a little anathematic for those who identify as old school, but the Mets are traditionally one step ahead when it comes to being excited for themselves, each other and us. Watch footage of the 1965 Dodgers heartily shaking hands when they won the seventh game of the World Series and compare it to how the Mets greeted one another in similar circumstances four years later. Follow the evolution of the high-five and curtain call as both came to represent the Met way in 1986 and consider how silly the rest of the league sounded when griping that it meant the Mets were arrogant. Search for images of when David Wright (2006) and Daniel Murphy (2015) waved fan-made signs celebrating divisional titles. The 2014 Mets, who didn’t win much, got the most out of every home run, simulating a dugout car wash under the supervision of the very veteran Curtis Granderson.

Your smileage may vary, but with all that ebullience as precedent, the tearing of jerseys and the injection of an extra letter into LGM is simply Met evolution in action. We don’t know what they’ll do for an encore. We just hope their future achievements provide the motivation to go suitably nuts.

We don’t know a whole lot of what will come next. We don’t know that this group will stay together and improve together. We want them to keep blossoming, keep blooming. We want to tell them, “OK, bloomers,” in the best sense possible. In our dreams, we might place Alonso at first, McNeil at second, Rosario at short, Davis at third, Smith in left, Nimmo in center and Conforto in right on March 26 and let them ride.

Yet they’re probably not going to make up seven-ninths of 2020’s Opening Day lineup. There’s a decent chance a segment of the seven won’t be with us next year. Trades of young players do happen, sometimes for the ultimate better. Hunt wasn’t here in 1969, but Agee, one trade removed from Hunt-for-Davis, was. We missed Hubie Brooks after 1984, but we were pretty darn delighted to have Gary Carter in 1985 and ’86. Dom Smith, his efforts at acclimating to left field notwithstanding, doesn’t really have a position, not with Pete Alonso having set up shop at first for, we pray, the next decade or two. J.D. Davis’s versatility isn’t quite as agile as Jeff McNeil’s. The Mets could use a legitimate center fielder, a catcher who every pitcher is comfortable throwing to, a fifth starter and bullpen reinforcements. To be distressingly businesslike about the whole thing, chips are chips. The team of our dreams is yet to be determined. It may or may not include those we came to love in 2019. If it does, we can’t be certain that the blossoming and blooming will continue unabated. We can project everybody’s prime all we want and be no more prescient than M. Donald Grant was about the trajectory of player salaries. We’ve been crossing our fingers and hoping for the best since Ed Kranepool. We don’t usually get Mel Ott.

Still, you’ll take what we’ve been given and build on it if you can. You’ll take more of Alonso going deep dozens of times; of McNeil throwing out a runner at the plate from right; of Davis magically sticking his glove out in left; of Rosario reminding you, oh yeah, he was supposed to be this good; of Conforto once and for all consistent beyond the doubt of all but the most cynical; of Nimmo working counts to perfection; and more of Smith loving being a Met like he did in the minutes after he gave us additional reason to love being Mets fans.

“It wasn’t about me, it was about this team,” Dom told Steve Gelbs after his eleventh-inning three-run home run beat the Braves in Game 162, which was merely his first at-bat in more than two months. “You know, we grinded all year, we fought all year, and we showed so much…”

After he was interrupted by a Gatorade bucket’s contents, he continued: “That just shows the character of the clubhouse. Twenty-five guys who came in every day, we grinded everyday, we worked hard. Obviously we didn’t get to where we wanted to go, but this is the start of something great.”

Again, we can only hope. But why wouldn’t we? After that night Conforto beat the Nationals? After that night Davis beat the Indians? After those nights Nimmo and Alonso waited out opposing pitchers to win via walks? After everything McNeil and Rosario did as their youth morphed into truly valuable experience? After Smith put an exclamation point on the remnants of a stretch run that made us believe the most unlikely of in-season comebacks was possible?

That circle of celebration on September 29, wherein nobody in or soon to be out of uniform was unexcited to be young, old or otherwise and a Met…the home run belonged to Dom, but the vibe that informed the euphoria clearly emanated from the entire youthful core. Dom and Michael and Amed and Pete and Brandon and Jeff and J.D. It felt like the curtain call for what they had brought us in 2019 and a sneak preview of what they might bring us in 2020.

Worst-case scenario, we’ll always have the memories they made.

FAITH AND FEAR’S PREVIOUS NIKON CAMERA METS PLAYERS OF THE YEAR

2005: The WFAN Broadcast Team of Gary Cohen and Howie Rose

2006: Shea Stadium

2007: Uncertainty

2008: The 162-Game Schedule

2009: Two Hands

2010: Realization

2011: Commitment

2012: No-Hitter Nomenclature

2013: Harvey Days

2014: The Dudafly Effect

2015: Precedent — Or The Lack Thereof

2016: The Home Run

2017: The Disabled List

2018: The Last Days of David Wright

Coming soon: The Top 100 Mets of the 2010s.

An entirely appropriate category, made all the more ironic given how this was totally not the plan of the Mets brain trust (pardon the expression). Remember, going into the season, the roster looked more like Cano, Frazier, maybe a platoon between Keon Broxton and Rajai Davis, and Jed Lowrie will be off the DL any day now, and maybe we’ll see that guy Cespedes (remember him?) by the All-Star break. McNeil’s reward for his borderline ROY 2018 season was to have his position taken away from him. J.D. Davis was noticed more for his pitching ability than what he brought to the plate. And the whole world had to beg the Wilpons to allow Alonso to start the season in the majors, despite his being the most ready rookie in Mets history.

I remember ’84 being another banner year for youth. But the only reason it was was because Davey Johnson stormed the offices and demanded that the suits allow the Goodens, Darlings and Backmans to replace their older predecessors. Carlos Beltran needs to do the same, or else we’ll find ourselves right back where we were last year.

Here’s hoping Jed Lowrie is healthy in 2020, if only to let us think something about him besides the fact that he never was in 2019.

“OK, bloomers.” Brilliant. A November line drive by the Great Greg.

And that “Bring Your Kids” ad is priceless.

Thanks for this wonderful and uplifting piece.

You’re welcome!

As the photo from the archives shows, we’ve seen young players before. Problem with those young players was that they might not have been all that much better than the literal kids posing in the picture with them.

This batch could be the real deal, and considering the Mets farm system is generally considered to be barren above Single-A, this is a good thing. It also means that the GM damn well better be at liberty to be a real live player in the free agent market. You want to sign these guys off the waiver wires, the Chasen Shreves of the world? Fine, but there also needs to be some big-time guys. Otherwise taking your kids to see our kids will still have a late-70’s feel to it.

The early ’20s feel feels a lot sunnier from this juncture of the very late ’10s.

Bam Bam Meulens as bench coach for a rookie manager . . . really???

Two years alongside Bruce Bochy likely counts for a doctoral degree in bench coaching.

Great writeup of the 2019 season! And, the orange and blue clutter in my basement has been ennobled by your christening it “The Will in Central NJ Archives”! Love it!

I’m applying to have National Register of Historic Places status applied to that clutter.

Greg–

Now I’m hearing–“Bring your kiddies, bring your wife…”

Another great article–makes me recall how Ed Kranepool & Ron Hunt were a glimmer of hope in 1963/64…

Let’s Go Mets!

Thanks Bob. Glimmers of hope are our lifeblood.

Meulens speaks Papiamento?

Anything to try to through to Cano.

Kore den promé het.

(Run to first base.)

Alright, you convinced me. I was ready to scream bloody murder when this wasn’t #LFGM but you went deeper and got to the root of it. Bravo sir.

#TYVFM!