Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

And when the morning light

Comes streaming in

We’ll get up and do it again

Get it up again

—Jackson Browne

On Wednesday night, October 2, 1985, at Busch Stadium, Tommy Herr batted for the St. Louis Cardinals in the bottom of the ninth inning with two out and the bases loaded, his Cards down by three. One massive swing from the St. Louis second baseman, who’d already driven in 108 runs, would win the game for the home team and effectively clinch the Redbirds a division title. But that was an unthinkable ending, because the pitcher Herr was facing was Dwight Gooden of the New York Mets, and in 1985, it was unthinkable that anyone, no matter how many RBIs he’d accumulated, could ruin one of Dwight Gooden’s starts with any kind of swing, dramatic or mundane. It was semi-unthinkable that any team would have the bases loaded against him or, for that matter, have two runs on the board as the Cardinals did.

All thoughts reverted to thinkable when Herr lined the final pitch he saw from Gooden in 1985 into Wally Backman’s glove. The Mets won, 5-2, and kept themselves alive for at least another night in the race for the NL East flag. Gooden won, too, raising his record to 24-4. With 10 Ks, his season strikeout total stood at 268. The two Cardinal runs, both earned, meant his ERA clocked in at 1.53.

That’s where it clocked out. Had the Mets taken the third game of this three-game series from the Cardinals as they had taken the first and second, and then continued to apply pressure when they returned home to play Montreal over the final weekend of 1985, perhaps Davey Johnson would have asked Gooden to pitch again on Sunday, on short rest. Or if the Mets and Cardinals were tied after 162 games, maybe Gooden would have been handed the ball on Monday for an all-or-nothing tiebreaker to decide the East. Had the Mets stayed hot and the Cardinals gone cold, vaulting New York over St. Louis before Sunday, the manager could have aligned his pitching for Game One of the NLCS versus the Dodgers. Barring something going terribly awry between October 2 and October 9, there’s no doubt Gooden would have pitched the opener in L.A., going against Fernando Valenzuela in a rematch of three previous 1985 dates.

This was all hypothetical, however. As it happened, the Mets lost the third game of their must-sweep series against the Cardinals on Thursday night, leaving them two behind with three to play. The race wasn’t over mathematically, but the Mets were all but done. Both teams won their Friday night games, keeping the Mets two behind with two to play. Alas, the Cardinals got the win they needed to make it official on Saturday afternoon, and that was that.

There’d be no postseason for the 1985 Mets. There’d be no World Champions flag to join 1969’s, no National League pennant to pair with 1973’s, not even an NL East banner for their troubles. But there was this: the greatest individual season ever recorded by a Met.

24-4. 268. 1.53. You could have embroidered that on a flag, run it up the pole in center and everybody who bled, sweated and teared up with those Mets would have stood to salute it.

Long may Dwight Gooden’s 1985 wave. For 35 years it has.

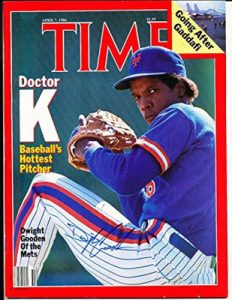

There was hardly ever a moment following Gooden’s debut on April 7, 1984, when he wasn’t The Man against men. His age only made his talent more tantalizing. Few pitchers could be as dominating as young Dr. K could be on a given night. Hardly any pitchers could overwhelm hitters so thoroughly as a rookie. Now factor in that he was a teenager two years removed from high school, pitching for New York instead of Tidewater because his first major league camp made him indispensable to the big club’s plans. The accelerated promotion was validated by performance. Except for a few perfectly reasonable bumps in the road as he got himself established from April to August, there was little wrong with what Gooden was doing on the mound.

Then, beginning on August 11, 1984, and extending to May 6, 1986, there was nothing — nothing — wrong with Dwight Gooden.

50 Starts

37 Wins

5 Losses

.881 Winning Percentage

25 Complete Games

12 Shutouts

404.2 Innings

412 Strikeouts

90 Walks

1.38 ERA

Maybe he didn’t hold baserunners on optimally, but there was barely enough of sample size to tell.

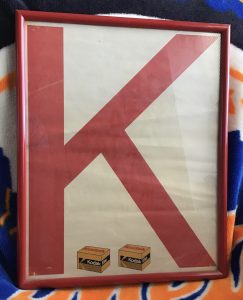

Firing a high fastball nobody could see and dropping a deadly curveball nobody could touch, Doc owned the National League. He could have brought it home to Tampa during the offseason and played with it in his front yard for fun. Instead, he displayed his abilities in our yard, a privilege for which we lined up anxiously to hail, whether with K cards dangling in left field, applause rising with two strikes or simply primal screams of exultation. For years and years prior to 1984, we wallowed in the second division, still licking the psychic wounds inflicted on us from when the Mets traded Tom Seaver. Finally, in ’84, we had a team definitively rising from those ashes, led by practically the second coming of Tom Seaver.

Maybe even better.

A Friday night at the end of July 1984 signaled the apprenticeship of Dwight Gooden, however brief, was nearing its conclusion. It was Doc vs. the Cubs at Shea, the first-place Mets striving to push back their closest pursuers, their ace charged with making the kind of statement Mets fans dreamed of being necessary to speak aloud for close to a decade. When was the last time the Mets had a big-time Big Game in which they had dealing for them the biggest deal you could have going? Probably 1975, Seaver vs. the Pirates on Labor Day. The start went well, but the rest of the month evaporated, so maybe 1973 — also Seaver, also September, also the Pirates — was more like it. Whenever it was, it had been forever. It had been that long since we had the best in the business taking the ball and shoving it down our foes’ throats with something significant at stake for all concerned.

In 1984, it was Gooden. It was all Gooden. For eight innings on July 27, he made the Cubs incidental to the showdown at hand. More than 51,000 were in attendance. If it wasn’t Doc’s strongest statistical outing of the year, it was his most critical. After allowing the top of Chicago’s order to cobble together a single run in the first (a stolen base was involved), he struck out Leon Durham and Keith Moreland to end their inning. The Mets immediately tied the game, and Doc proceeded to brush aside every ensuing threat. The Cubs thrice placed runners on third, once on a leadoff triple. Gooden’s blend of power and poise snuffed each potential rally. Batting in the seventh, he bunted Rafael Santana to second, enabling Wally Backman to drive in Raffy with the go-ahead run. All told, Doc went eight, struck out eight and earned his ninth win. The Mets were now 4½ in front after 96 games played.

We didn’t know it, but that was the high point of the season for the Mets as a unit. The Cubs would win the next three games of the series and sweep four at Wrigley soon after. Though the Mets would stay within shouting distance of first into September, and no Mets fan gave up on dreaming until mathematics sealed our fate, the race was pretty much decided by August 8.

But the most spectacular stretch of pitching ever rendered by a New York Met was about to begin. It started on August 11, at home to Pittsburgh. Gooden entered with a record of 9-8 (we took won-lost records very seriously in those days) and an ERA of 3.42. Punctuated as it had been by eight double-digit strikeout totals to date, a no-hit bid in Pittsburgh in June, and an All-Star appearance in which he struck out a side of American Leaguers in July, it would have been gauche to complain let alone note that his previous two outings — 3 IP, 7 ER at Busch; 4 IP, 5 ER at Wrigley — were more typical of a rookie beginning to run out of gas.

Apparently Doc had stopped to fill up on the way back from Chicago, because, brother, did he get the lead out. That and basically every batter in a Pirate uniform. He went seven innings that Saturday night, long enough for Gooden to strike out 10, which allowed him to surpass Jerry Koosman’s Met rookie strikeout record. Kooz fanned 178 batters in all of 1968. Doc was at 181 and counting with another seven weeks to go.

Go, he did. The Pirate game was the last time in 1984 Gooden pitched as few as seven innings. His next three starts each lasted nine, as did a pair in September. The other three measured eight. Each of them encompassed at least nine strikeouts. Two, in succession, featured 16 apiece. Those came after a one-hit shutout of the Cubs that was a highly questionable scorer’s decision from standing as the first no-hitter in Mets history. Only one of Gooden’s final nine starts — a stretch during which is earned run average measured 1.07 and the league batting average against him amounted to .160 — wasn’t a personal or team win. That lone loss, at Philadelphia, could be traced to an unearned run in the sixth and a balk in the eighth. Unfortunate, to be sure, but since it was on one of the nights when he struck out 16, it wasn’t exactly a cause for recriminations.

Doc carved his image in those weeks: long, lanky, fluid and demonstrably indefatigable. From August 11 through September 23, Dwight Gooden threw 76 innings, struck out 105 batters, set a new major league rookie strikeout mark with 276, finished overall at 17-9 with a 2.60 ERA, and ensured he’d finish a solid second to Rick Sutcliffe in NL Cy Young voting. And did we mention he was 19?

What would Doc Gooden do for an encore? He’d do 1985. He’d do it from beginning to end and he’d do it like nobody we ever saw.

The most curious feature of Doc’s ’85, I’ve long thought, is there really isn’t one standout game among his 35 starts that ever gets brought up when discussion turns to the greatest pitching performances in Mets history. When that chestnut of a topic arises, we instinctively go to Seaver’s imperfect game and Tom’s ten straight strikeouts; to Bobby Jones’s one-hitter and Jon Matlack’s two-hitter, each proffered amid playoff pressure; to Johan Santana holding together a stretch drive with one hand while slamming shut a creaky bullpen door with another; to Al Leiter freezing in place the Reds to gain the Mets a Wild Card; to R.A. Dickey’s mesmerizing one-hitter, at Tampa Bay, when he reeled off the first of two of those in a row; to Koosman putting the Birds in their place in Game Two of the 1969 World Series and putting Ron Santo and the Cubs on notice that September; to Matt Harvey being almost flawless versus the White Sox even as his nose bled; to David Cone rolling out a 19-strikeout gem on the final day of a season that ended with the cops waiting in the wings of the Vet to ask him a few questions; to Rob Gardner going 15 this-is-not-a-typo shutout innings in 1965, even.

It’s possible the most famous Dwight Gooden start of 1985 is one where his participation served as prologue rather than plot. Doc started on July 4 in Atlanta. July 4, 1985, in Atlanta is best known for lasting until 3:55 AM on July 5, with the Mets winning, 16-13. Rain, not the Braves, knocked Doc out in the third. Perhaps the “16” in the final score was the Mets’ way of saying they remembered ol’ young No. 16 pitching when the night/morning began hours and hours earlier. Less remembered is May 15 in Houston, though maybe it oughta be. That night, Davey removed Doc after the Astros strung together a double and a single to cut the Mets’ lead to 4-3 with one out in the seventh of what, with Jesse Orosco’s help, eventually became Doc’s sixth win of the year (despite Dr. K getting all but one of his outs without notching a K).

What those two games have in common is they are the only games from 1985 in which Doc left the mound mid-inning — and the July 4 instance was weather-induced. Gooden pitched 276.2 innings in ’85. The “.2” are a third-of-a-inning from May 15 and a third-of-an-inning from July 4. Otherwise, if it ever occurred to Johnson to take the ball from his ace’s hand, he didn’t act on it.

That leaves 33 starts.

The afternoon of August 15 at Shea was steamy for all. The schvitziness seemed to make Doc unusually uncomfortable — 5 IP, 5 ER — but the matinee conditions were too hot to handle for his opponent, none other than Jerry Koosman, at this point nearing retirement in a Phillies uniform. The Mets won, anyway. The Mets also won in conditions better suited to the Iditarod, on Opening Day, when Doc reached only the baseline of the trendy new term “quality start”: 6 IP, 3 ER. Gooden certainly gave his teammates every chance to win, which was the idea of labeling a start of no fewer than six innings allowing no more than three earned runs quality, and win they did, on Gary Carter’s “Welcome to New York” tenth-inning homer. If anybody was measuring Doc’s ERA after one start, it was an unsightly 4.50.

That leaves 31 starts.

Doc pitched well enough to win (7 IP, 2 ER) on April 24 in St. Louis, but didn’t; Joaquin Andujar, who’d won 20 the year before and was going to win 21 this year, held the Mets scoreless until the ninth. It was Gooden’s first loss. His second and third defeats, back-to-back in late May versus San Diego and Los Angeles, could be described in a similar manner. In each case he was outpitched by a former Cy Young winner who’d join him and Andujar on the ’85 NL All-Star team — LaMarr Hoyt of the Padres, Fernando Valenzuela of the Dodgers. At the end of August, Gooden lost to a less-credentialed starter, Jim Gott of the Giants. Gooden’s six innings of two-run, six-hit ball simply wasn’t (as headline writers never tired of printing) Goodenough.

Those were the four losses in 24-4. Add those to the tiny stack of the aforementioned not wholly satisfying Dwight Gooden 1985 outings — the exceptions — and that leaves 27 starts.

Those 27 starts, the wholly satisfying ones, were the rule from when Doc ruled. The Mets went 24-3 in those starts. Doc himself went 20-0. The four Doc no-decisions and three Met losses were mostly a product of the offense going into sleep mode or the bullpen blowing up. Every last one of them may not have been a gem, but none deserved to be classified cubic zirconia. Actually, most of them were gems. There were so many pitched so consistently that after a while it didn’t seem worth sorting one from another to determine which sparkled most. Plus, when you consider that from Day 1 to Day 161 the Mets were intensely engaged in trying to capture the division title that had eluded them in 1984, you realize there was little time to bask in any one start, Gooden’s or anybody else’s.

Probably the Met start that stands apart from all its peers in 1985 was thrown not by Gooden, but by Ron Darling. On October 1, the night before Doc kept the Mets alive with his fairly routine complete-game 10-K win, the one that brought him to 24-4, Ronnie crafted a masterpiece: 9 IP, 4 H, 0 R versus the closest thing the Cardinals or anybody in the NL had to Gooden, John Tudor. Tudor went 10. The Mets won in 11 on Darryl Strawberry’s home run off the clock. It is remembered better than any of Gooden’s non-July 4 starts from 1985, partly because Darling is ensconced in the Mets’ broadcast booth, partly because, though Darling was a fine pitcher for many years, it was a bit of an anomaly. Usually he was good. That night he was great.

What Darling did on the first night of October, Gooden did basically every five days through the month of September. In the heaviest month of the year in the fiercest year the Mets had ever contested to that point (from July 29 to September 24, the Mets and Cardinals traded first and second place continually, with the Mets never more than a game ahead of the Cardinals and the Cardinals never more than three in front of the Mets), Doc started five times. He compiled 44 innings of must-win work that yielded an earned run average of 0.00.

Grab yourself four paper clips, attach those five games and call that the greatest starting pitching performance in New York Mets history. Or, given the time of the season and the franchise at the time, the greatest finishing kick. This was, lest you’ve forgotten amid the stream of statistical superlatives, from a 20-year-old whose first five months of ’85 indicated any September brilliance to come would hardly be anomalous.

• On July 14, the night before the All-Star break, when the entire Metsian enterprise held its collective breath at word that Carter’s knee was acting up, he threw a five-out shutout over the Astros with rarely deployed Ronn Reynolds sitting in behind the plate for the premier catcher in the game.

• On July 30, amid a five-hit shutout of the Expos, he stood up for Carter by brushing back Bill Gullickson after Carter’s former batterymate had brushed back Gary — just as Koosman had done to Santo in retaliation for Bill Hands’s close shave of Tommie Agee on September 8, 1969.

• He’d surpassed 200 strikeouts for a second time, on August 20, the same night he struck out 16 in a game for the third time, versus the Giants at Shea (the fans in attendance expressed dismay when Keith Hernandez dared to catch a foul pop).

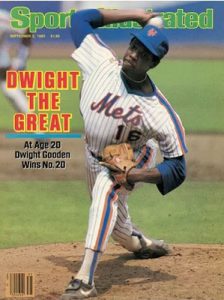

• He’d broken Seaver’s consecutive in-season franchise record for wins, 10, on August 4, the same afternoon Tom was earning his 300th career win, and kept it going until it reached 14, which it did on August 25, the same day he won his 20th game…at the age of 20, a feat Sports Illustrated saluted by labeling him “Dwight the Great”. Alexander the Great, who did his pitching in the Macedonian League, also ascended to his throne at the age of 20.

This was all before September. It had earned him attention and accolades and unquestioned status as the best pitcher in baseball.

It was an appetizer.

September was Doc shutting out the NL West-leading Dodgers for nine innings on the 6th, versus Valenzuela doing the same to the Mets for eleven, until Strawberry won it in the thirteenth.

September was Doc shutting out the rival Redbirds for nine innings on the 11th, while Tudor did the same for ten (if it wasn’t the year of the pitcher, it was sure a helluva year for certain pitchers), until Cesar Cedeño beat Orosco in the tenth.

September was Doc shutting out the Phillies on the 16th, a comparatively stress-free route-going effort, what with the Mets scoring nine.

September was Doc taking off the ninth inning gasp! in a 12-1 rout of the Pirates on the 21st after double-gasp! giving up an entire run, but, relax, it was unearned and, besides, the pitcher made up for the faux pas by belting a three-run homer that he admitted he treasured more than the thought of tossing a no-hitter (Doc was batting .230 when he said it, decent for a slick-fielding shortstop, outstanding for the defining pitcher of his day).

September was Doc returning to complete-game form by shutting out the Cubs on the 26th, a game the Mets so desperately needed to maintain their fading pennant-race viability, that this was how Keith Hernandez summed up the entire game in his deeply textured day-by-day diary of the 1985 season:

“Thank you, Doc.”

Yes, thank you, Doc. Thank you for September 1985. Thank you for all of 1985. Thank you for 24-4, 268 SO, 1.53 ERA, that last figure the lowest in baseball since Bob Gibson’s 1.12 in 1968 — and the lowest still. Thank you for your unanimously awarded Cy Young. Tudor was great for St. Louis that year. Andujar was, too. Valenzuela and Orel Hershiser personified the Dodger pitching tradition established by Koufax and Drysdale a generation or two before. Tom Browning won 20 as a rookie in Cincinnati. Darling, 16-6, wasn’t too shabby.

But there was no pitcher on Dwight Gooden’s level. No player, either, even if the apples and oranges flummoxed the BBWAA when it came to Most Valuable Player voting. Doc placed fourth in that balloting despite compiling a Baseball-Reference WAR of 13.3, dwarfing sanctioned MVP Willie McGee’s total by more than 5. Obviously Wins Above Replacement was an unknown concept in 1985, but the eye test and a scan of extant statistics should have been enough. Or as Wally Backman kidded his teammate after the Mets finished three behind the Cardinals, if it hadn’t been for you losing those four, Doc, we would have won the division.

The encores for the 98-win Mets and their 24-win ace were, as they’d been after ’84, breathlessly awaited. How could they not be? The Mets had come so close to beating the Cubs, even closer to beating the Cardinals. All the Mets had to do was win a few more games to take the East at last. All Doc had to do was be maybe just a little better, right?

Kidding aside, it didn’t seem preposterous that as long as Gooden was providing a touchstone for 1968 comparisons that maybe he could win 30 in 1986, making him the first 30-game winner since Denny McLain eighteen years before. Really, on an individual basis, what else was left him for him to accomplish inside a season?

Bad Cardinal karma got in the way of a happy Home Opener six days later, but Doc pitched just swell — eight innings, five hits, two runs. Then he threw a couple of complete games, the second of them a shutout of St. Louis as the Mets began to fully feel their 1986 oats. When Doc beat the Braves on April 30, it made him 4-0 and the club 13-3, riding an eleven-game winning streak.

The Mets were off to the races. We were too nervous to completely accept it, but the division was clinched in everything but name before May Day. The Expos would stay conceivably close until late June, but the Cardinals disintegrated and nobody else posed a challenge. We were reveling daily in what the Mets were doing for an encore to 1985.

Judging by April, Dwight Gooden was on the same course as his team. On May 6, it was more of the same as Doc shut out Bob Knepper and the Astros at Shea on two hits. Knepper had come in at 5-0. Gooden now had that very same record to go along with his 1.04 ERA. The encore everybody’d asked for was going splendidly.

Then it…well, it didn’t go off the rails by any means. But starting on May 11, versus the Reds, Doc proved the slightest bit penetrable, maybe even defatigable. Cincinnati loaded the bases in the second with two outs. Less than a year earlier, Doc faced the same situation at Dodger Stadium, but worse. There was nobody out then. What did he do in L.A.? He got out of the jam: strikeout, foulout, strikeout. He went on to beat the Dodgers and Valenzuela that night, elevating his legend in the process.

That was 1985. This was 1986. Usually when one invokes 1986 where the Mets are concerned, it’s all legend and all good. But here the Reds brought their own legend to bear. Batting with the bases loaded and two out was Pete Rose, player-manager and not incidentally all-time Hit King™. Rose had faced Seaver, Koosman, most every Met starter of stature since 1963. Pete hadn’t lasted 24 seasons being intimidated by the greats, even a great on the greatest roll of the post-Gibson, post-Koufax era.

“I’d rather have his future than my past,” Koufax said of Gooden in 1985. Gibson’s two cents on the subject were, “He can’t get any better,” which could have been taken as a extraordinary compliment or a word of caution.

On May 11, 1986, Dwight Gooden stopped getting better. Or stopped staying as good as he’d been for the preceding fifty starts. He worked the count full to Rose until, with all the runners in motion, Rose connected. It wasn’t close to the hardest ball Charlie Hustle ever hit, but it didn’t have to be. The 45-year-old part-timer lined a ball just above the reach of second baseman Tim Teufel. It ticked off the new Met’s glove and spent enough time in right to score all three runners. Rose hustled only as far as first.

A three-run single. It would be absurd to refer to it as Doc Gooden’s undoing, but since when did Doc give up a three-run anything? The Mets trailed and lost. It snapped their latest winning streak at seven and dropped their overall record to 20-5. They’d get over it.

Doc went only five in going 5-1. The only game when he went no more than five in ’85 were the bizarrofest in Atlanta on July 4 and the sweatbox at Shea on August 15. So just chalk it up as one of those days, right? The next start was closer to Goodenesque — eight innings, seven strikeouts, all three runs scored against him were unearned — but the Mets lost. The Mets lost his next start, too, a 10-2 thrashing of Doc the likes of which hadn’t been seen since he was a rookie. He was 19 then. He was 21 now. He was supposed to be past his apprenticeship.

I don’t remember exactly when I consciously drifted into referring to Doc Gooden as my favorite player in the active sense. There was Tom Seaver, who was my favorite of all-time, even if he started 1986 with the White Sox and ended it with the Red Sox. That status was and is etched in my heart forever. After Tom, though, there was Doc. I didn’t see the majority of Gooden’s starts in 1984, spending the spring and first half of summer at college (in his hometown of Tampa, ironically), but what I did see, let alone what I gleaned from box scores and wire copy, began to win me over. When I listened to him best the Cubs on July 27 in the final season I lacked cable, I think I knew for sure he was my guy. There were a plethora of personable, appealing Mets to choose from by 1985, but the fella who threw the first pitch of the year started and ended the conversation for me. Other than Seaver, Gooden was and is my favorite player ever.

I bring that up here because starting in the aftermath of Rose singling in those three runs in the second inning on May 11, 1986, I instinctively grew insanely defensive in response to anything anybody had to say about Doc Gooden being off his game, not being what he’d been in 1985, being only good not great.

HOW DARE YOU? Mind you, this conversation mostly took place internally, in my head, but that’s how I felt. What was it Keith said after that shutout in Chicago? Thank you, Doc. I never stopped being grateful for 1985, and I never wanted to admit that 1985 was once in a lifetime; that whatever Sandy Koufax’s future held after 1985, he probably should have held onto it vis-à-vis what Gooden’s had in store; that the double-edged observation Gibson made was as correct as could be from the cautionary perspective.

How could anybody expect anything better than 1985’s Dwight Gooden? You’d be crazy to. But we were crazy then. I was crazy then. Too crazy for Doc’s own good. I sat on the phone during the offseason leading into 1986 with my Mets-loving friend from high school, Joel Lugo, and mapped out what each Met pitcher should (not could; should) do in the way of winning and losing in the year ahead. We agreed that Doc should go 30-2.

Doc went 17-6. Most of Metsopotamia seemed apologetic about it. Or apologetic about being apologetic. Pitchers occupying only a slightly lower plane than Sandy Koufax’s would have traded their past for 17-6, a 2.84 ERA, 200 strikeouts on the nose. Yet Gooden was suddenly not on Gooden’s plane. Others had ascended while he descended to merely Goodenough. In Boston, Roger Clemens had Gooden’s won-lost record from 1985: 24-4. In Houston, Mike Scott won Gooden’s Cy Young and plaudits from 1985. He threw a no-hitter to clinch the NL West and send up a warning flare for what the Eastern Division champion Mets could expect by way of a postseason obstacle course.

Gooden versus Scott, Game One. Doc was great enough in a 1-0 loss. Scott, whether he scuffed the ball or not, was far better. I’d prefer to call it a draw. It wasn’t. Someone in the National League was outpitching Dwight Gooden when it counted most. Same in Game Five, though that really was a draw. It was Gooden vs. Nolan Ryan, a matchup dripping with symbolism and strikeouts. Ryan, the old master, was dazzling. Gooden simply got the job done. Each man gave up only one run. Neither man was involved in the decision, a Mets win Carter took care of in the twelfth. Stylistically, however, old Nolan outdazzled young Dwight.

The World Series brought Gooden head-to-head with Clemens. They were both disappointing when they clashed, but Gooden was more so. The Red Sox won his Game Two start. Then Hurst and the Red Sox thoroughly bested Doc in Game Five. The Mets lost three games of the seven-game World Series. Dwight lost two of them. Pitching to an ERA of eight, it seemed sacrilege to refer to Gooden as Doc.

But the important thing was the Mets won four of those World Series games. The Mets were world champions. All of them, right up to their 17-6 ace, the righthander who thrust them on the map in 1984 and levitated them close to the top of the standings in September 1985. OK, I’d admit to myself when nobody else was around, he wasn’t quite what he’d been. But, c’mon, who could have been? He deserved his World Series ring as much as anybody else. He deserved to absorb the love and confetti of the championship parade the next day as much as anybody else.

The coke was keeping me up. The booze had been keeping me mellow, though not much anymore. Both of them had clearly wrecked my judgment.

The sun through the window slammed me hard.

“Uh-oh,” I finally realized. “That’s not good.”

It was after six thirty by then.

The above passage of what it was like to have the morning light come streaming in when it’s the last thing you want to see is from Dwight Gooden’s 2013 memoir, Doc (written with Ellis Henican). It describes the morning of October 28, 1986, the morning that should have rated among the best of Gooden’s life. He was a newly minted champ. The parade that the Mets earned by dint of those four Series wins on top of the four NLCS wins on top of the 108 wins in the regular season awaited. Every Met who deserved a parade got one.

But one wasn’t there to get it. Unbeknownst to any of us who crammed into Lower Manhattan to strain for a peek of our heroes or anybody watching on TV, Dwight Gooden was not in attendance. On Channel 4, one of the reporters said we couldn’t see Doc on screen at the moment, but that was because he had just gone to be with his wife.

Nope. Doc had gone to be with cocaine. That was after Game Seven, after the World Series was won. Gooden recounts it heartbreakingly in his memoir. You so want him to be there on Broadway. You so want him to step up to the podium at City Hall. You so want there to exist footage of him accepting his key to the city that glorious October afternoon, just as you want to go to YouTube, enter “Gooden World Series ring ceremony Opening Day 1987” and find a clip that’s a perfect match.

But nothing is perfect in the Dwight Gooden story, at least not once we learn cocaine entered it. We didn’t find out until the following April Fool’s Day. I swear I thought it was a sick April Fool’s joke when I’d heard he’d been suspended, over WNEW-FM shortly before one in the afternoon. They were going on about how Doc was perspiring during his World Series starts, that something clearly wasn’t right with him, and now we know why.

Cut it out, lame-ass disc jockey. It’s not funny.

No joke, Doc tested positive for cocaine, was suspended by baseball, went to rehab, came back to the Mets eventually and, no, it wasn’t the same as before April 1, 1987, when this incredibly likable, admirably humble young man (he was only 22) had to admit first to his family, his team and the world that he had done that thing we were all warned against in school. No matter how I wished it so, it would never be the same as before Rose’s three-run single on May 11, 1986, that golden period from August 11, 1984, through May 6, 1986, encompassing all of platinum 1985. Just to reiterate:

50 Starts

37 Wins

5 Losses

.881 Winning Percentage

25 Complete Games

12 Shutouts

404.2 Innings

412 Strikeouts

90 Walks

1.38 ERA

Of course he couldn’t get any better. Of course he couldn’t stay exactly as good. But, Doc…cocaine? Seriously, man, 17-6, 2.84 and 200 strikeouts on the nose was still very good.

What I and most Mets fans weren’t in the mood to understand, or perhaps were not capable of understanding, was that addiction doesn’t act as a choice, that it’s not so simple, without a whole lot of effort, to choose to just say no, as they used to advise in the ’80s. Doc Gooden was an addict. His addiction was stronger than his pitching. It took an enormous effort go get through every inning of his future once he came to grips with that fact.

Set against an ongoing battle against addiction, going 15-7 in 1987, as Doc did once he returned to Shea on June 5, is pretty fricking remarkable. Ditto 18-9 in 1988, 9-4 in injury-shortened 1989, 19-7 in 1990 and 13-7 in 1991 before another injury interrupted him. These were, if you pulled back from the overwhelming excellence of the original production, solid encores. He was still Dwight Gooden, topflight pitcher for the New York Mets all those seasons. In my heart, he was still the best there was. My head wouldn’t entertain arguments to the contrary, no matter how much inevitably further time ticked onward from 1985. I loved Doc hard in every one of those years. The years directly after them, too, no matter what came up. He endured losing records in 1992 and 1993, but the whole scene at Shea had deteriorated. To win in double figures as he did (10-13, 12-15) was also pretty fricking remarkable.

Then came 1994 and a downturn in his battle against addiction. Another positive test, another suspension. He didn’t last the year with the Mets or in the majors. He was absent through 1995 and reappeared in New York as a Yankee in 1996. On May 14 of that year, I did something I’ve done wholeheartedly exactly once in my life. I rooted for the Yankees to win a game. Dwight Gooden was pitching a no-hitter. He got it. As with Seaver’s 300th, I’d have rather he’d gotten it for us and not at Yankee bleeping Stadium, but the important thing to me was that he got it.

Doc pitched until 2000, winning 194 games overall (157 for the Mets, second to Seaver). We saw him at Shea for one more regular-season start. He had left the Yankees, succeeded in Cleveland, struggled for Houston and Tampa Bay and was granted one of his many final shots by George Steinbrenner. Gooden started on July 8, the afternoon half of a day-night, two-stadium doubleheader. There was little time to savor Doc’s presence in Flushing. The Mets had been jobbed by a rookie ump in the top of the first, and every run and out mattered to death in those years, so it was hard to focus on a beloved if fallen icon’s homecoming, especially in the uniform it insisted on getting itself wrapped in. Still, it was Gooden on the mound at Shea. I applauded softly from afar. He went five and got the win. That night, his teammate Clemens beaned Mike Piazza. Life sure had gone on, huh? Dwight lingered in the Yankee pen clear through the World Series, which ended at Shea, not happily. He didn’t pitch, we didn’t win.

Soon he’d be not pitching at all and dipping in and out of various strata of trouble as a civilian, and all I could do when his name made news was shake my head and hope for the best, which used to be synonymous with him on the mound but now meant I sure hope he keeps living. Seeing him one final time at Shea Stadium, the Sunday in September 2008 when they closed the park, was his and my reward for him surviving. I cried a lot that day. I cried the most when my second-favorite player ever appeared wearing No. 16 with the racing stripe.

Correction: this was Dr. K.

Correction: this is Dr. K.

I want to be clear. He’ll always be Doc to me. Sometimes in writing about him I’ve decided to practice toughlove on him by referring to him only as Dwight, as if that would show him to not give into his addictive demons. I’m sure it was quite helpful.

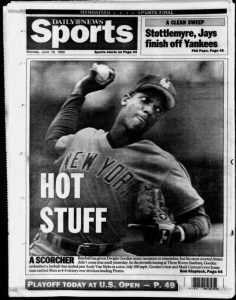

This last part isn’t about 1985, not directly, though, really, it’s always about 1985 where Doc Gooden is concerned. It’s about his outing of June 17, 1990. Doc was off to a choppy start that season. All the Mets were. It got Davey Johnson fired. But in June they started to get their act together. The Mets were in Pittsburgh taking long aim at the first-place Pirates. It was gonna take a whole lot of doing to catch them, but the Mets were commencing to resume serious contention. On this particular Sunday, Doc shook off whatever was troubling his right arm and the rest of his body and really delivered whatever he had to home plate. That day, according to the speed gun at Three Rivers Stadium, his fastball hit 100 MPH. It wasn’t 1985 anymore, but he had just thrown the hardest pitch of his career.

If it was 1985, there’s an excellent chance I would have watched Doc on a Sunday afternoon with my parents, neither of whom had been any kind of a Mets fan until 1984, and then, suddenly, I found them alongside me on the bandwagon I’d never left. Winning will do that, and I’m in favor of it. The more, the merrier. My dad and my mom both dug Doc. I imagine a lot of mothers and fathers across the Metropolitan Area did. We watched that final win of 1985 together, and that whole series against the Cardinals. We watched the game against Valenzuela that went thirteen from the West Coast. My father thought it amusing that Ralph Kiner pronounced Gooden’s given first name with two syllables: “Duh-wight.” My mother automatically perked up when she saw in Newsday that he was starting.

On Sunday, June 17, 1990, Gooden started, touched a hundred on the radar, evened his record at 5-5 and pushed the Mets within six games of first place. An eleven-game Mets winning streak was about to ensue, which, once it concluded, would have the Mets percentage points in front of the Bucs. I remember the date and circumstances with great specificity because Sunday, June 17, 1990, was also the day my mother died, about a month shy of her 61st birthday. She’d suffered with cancer for nearly two years, and our family was on high alert that the end was nigh. When my sister called me not long after the game with the news and told me to come to our father’s house, one of my first thoughts was, “Look who pitched today.”

Doc was still only 25 then. Was he ever not young?

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1967: Al Schmelz

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1971: Tom Seaver

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1974: Tug McGraw

1975: Mike Vail

1976: Mike Phillips

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1986: Keith Hernandez

1987: Lenny Dykstra

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1997: Edgardo Alfonzo

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2011: David Wright

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2017: Paul Sewald

2019: Dom Smith

2020: Pete Alonso

Just gorgeous. I remember the Saturday Game of the Week in 1984. I was living in Florida and suffering because I couldn’t get a regular fill of this phenom. But on that day, I did. I was wowed. I thought of him as the next Seaver. He wasn’t. But he still has written his name in stone as one of the greatest Mets.

Greg,

Brilliant work. Thank you.

Absolutely beautifully written. You encapsulate all the joy and tragedy that was Doc Gooden.

The thing I always wondered – if the Mets hadn’t lost Tom Seaver to the White Sox before the ’84 season, could he have been a steadying influence on a young Gooden? We’ll never know.

Beautifully done, Greg. A wonderful tribute to our most complex Met. Seems many of us have stories from life that Doc ties into. When I mention that he was the starting pitcher on the day we got married, it never fails to get an eye roll.

I’m sorry that younger Mets fans never got to see him. When the Mets owned New York, it was more thanks to him than anyone. His starts were events. Seaver had the better career, that’s indisputable, but even he never had a season like 85 Doc. I hope Doc has gotten past his demons. He deserves a happy life.

That’s a lot of greatness and a lot of abyss for just one article.

Sigh.

Great tribute to Dr K, Greg !! I actually was at the Aug , ’85 game where Gooden broke Seaver’s record for wins . It was during a road trip to Wrigley Field in Chicago. What a memory !