After the Major League Baseball lockout ends; after Spring Training goes through its motions; once the regular season begins; and whenever Eduardo Escobar takes the field at third base in 2022, he’ll achieve a Met milestone instantly recognizable to viewers of An Amazin’ Era, the videocassette that commemorated the franchise’s 25th-anniversary. Pending unanticipated roster moves and managerial prerogative, Escobar projects as the 179th man on third in Mets history, or 100 beyond the total as it stood when the ballad “79 Men on Third for the Mets” lit up the celebratory VHS the Mets released in 1986. As a refresher, Dick McCormack’s ditty went a little something like this:

Well, the Mets are really rockin’ that ball

But they can’t keep a man on third at all

Like Drake and Chacon

Fernandez, Ramirez

Pfeil and Graham

Maddox, Martinez

It’s a brilliant composition, albeit reflective of a less than sparkling heritage. The Mets had their problems keeping a man on third — not to be confused with their problems getting a man to third — and for the better or perhaps worse part of a quarter-century, they were regularly groping for solutions. For example, the 79th man on third for the Mets was Tim Teufel, who despite not really being a third baseman, was given a whirl at the hot corner on April 12, 1986, three games into what became A Year to Remember (speaking of classic video productions). Kudos to McCormack for staying alert to Met box scores and having the quantity current for when An Amazin’ Era screened for the press on July 8 of the Mets’ 25th annum.

The Mets being the Mets, even in their most spectacular season, rendered McCormack’s cataloguing out of date within two weeks. On July 22, the Mets deployed their 80th man on third, a fella named Gary Carter. Bright-eyed observers will recognize the occasion instantly. A clip of Carter playing third has made the social media rounds of late because it’s an example of the defensive handiwork of the finest first baseman the Mets have ever called their own and the holder of the most recently retired number in Mets history, Keith Hernandez. No. 17 got himself up in the face of Reds batter Carl Willis. Willis, a pitcher, had been called on to bunt. Bunting to Hernandez was rarely productive for the team on offense. Keith fielded the ball, flung it to third baseman Carter, who effected a forceout where he was stationed for the second time in his big league career, and relayed it to Teufel, second baseman covering first. Score it 3-5-4, with a Hall of Fame catcher manning the middle of a double play that kept a twelfth-inning tie knotted tightly.

Two innings earlier, Carter became the 80th third baseman in 24½ years of Mets baseball amid what manager Davey Johnson called “the strangest game I’ve ever been involved in,” and Davey managed the Mets a year earlier through a 16-13 19-inning jaunt to daylight in Atlanta. As you likely remember or have had mentioned to you at some point in your Met-loving life, July 22, 1986, was one of those nights (there were four) when the 1986 Mets got into a fight and a night when they experienced multiple ejections. With the bench depleted, Kid had to defend a spot he hadn’t visited as anything but a baserunner since August 8, 1975. Plus Jesse Orosco played right field and Roger McDowell played right and left field, in addition to both of them pitching.

But we’re getting a little off the track here.

The point, to the extent we need one in the middle of a lockout, is Eduardo Escobar is likely to be the 179th man on third base for the Mets. But will he be the 81st member of another subset of Mets third baseman? A club of which Carter is a member? A club of which Carter might be a card-carrying member had his card been printed to reflect his particular accomplishment in this realm? Not too many of those 80 guys got cards.

I’m talking about Mets third basemen-outfielders. And Mets outfielders-third basemen. It probably makes a difference which position you place before the hyphen. For many years while the Mets were trying to keep a man on third, they’d look all over the diamond for a solution. Even to the outfield…though sometimes they’d have holes in the outfield and seek help internally…even from third base.

The similarities between third base and any of the three outfield positions appear fleeting at best. According to a reputable-looking coaching website, here are what high school third basemen should feature:

• A very strong arm

• Excellent reflexes

• Great defense, if not with as much range as a shortstop

• Power

The reflexes are the first thing that occur to me. Balls come at a third baseman, if he’s not in a shift (in which case all assumptions are inoperable), fast and at tricky angles. Line drives are somehow both common and total surprises. Diving to one’s right is a must. The arm needs to unleash clothesline throws to first. Range requirements depends on who’s batting. Power has nothing to do with defense, but, yes, third base is often where we look for slugging when our team comes up to bat.

Not that much of it sounds like the outfield. A strong outfield arm has different utility than a strong infield arm. The ball tends to be in the air longer (and higher) if it’s headed for left, center or right. Defense relies more on speed out there. Power, of course, is swell, depending on other assets and the rest of your lineup.

In high school, a player may still be finding his position. In the majors, you’d figure you’d have your expertise boiled down to suitability with a given outlet. Shortstops can slide over to second. Second baseman can trot over to third. A right fielder oughta be able to play left. An aging catcher, given his experience with a mitt, might later settle in at first. And in a pinch, almost anybody should be able to give you an inning almost anywhere. Pete Rose played all three bases plus the corner outfield spots, and you can bet it was for more than an inning.

Yet I can’t wrap my head around the OF-3B/3B-OF paradigm, not as a way of life.

This has fascinated me at a low level for as long as I’ve been a Mets fan, which is a long time, but isn’t quite as long as there have been Mets, which may explain the fascination. Between 1962, our founding, and 1969, when I started rooting, outfielders and third basemen doubling as third basemen and outfielders seemed to be normative. Upon my introduction to the game, I grasped quickly that every team sent nine men into the field. But why were the Mets less than secure about who they sent to play third?

I understood, thanks to Lindsey Nelson, Ralph Kiner and Bob Murphy regularly touching on it, that it was more than a fleeting concern. From the earliest days of my fandom, I got that the Mets hadn’t been satisfied with their third base situation from their earliest days. The first trade I remember was for a third baseman: Joe Foy, in the offseason following 1969. We’d traded Amos Otis to get him. Amos Otis became an All-Star center fielder in 1970, my first full season as a fan. It was mystifying to my seven-year-old mind that somebody considered among the best players in the game was also somebody the Mets gave up on despite perhaps needing somebody considered among the best players of the game. More mystifying was learning the Mets had tried to make Amos Otis a third baseman.

But that (an episode we’ll dig into in a future installment of this series) was hardly the first time they attempted to pull the OF-3B conversion, nor the first time it didn’t take. You can go back to practically the beginning of the Mets to find dissatisfaction on third and an outfielder being tabbed to make it go away.

“Well, now you’re gettin’ down to Mister Zimmer. Mister Zimmer’s been handicapped five or six times in life because he was injured, but he never gives up. He’s a boy that don’t die. Now ya gotta have that spirit and ya gotta have somebody that won’t give up and plays ’til the ninth inning. If they’ll play ’til the ninth inning, then ya just beat a team six to five, instead of gettin’ beat five to four. Now if you can win six to five, you’re better off than losin’ five to four. Now if I can get the teamwork now, to go with those men that are on that infield, we oughta find some method in which we can come out winning a number of games that otherwise their records will not stand. We don’t care what their records were last year. It’s what’re ya gonna do when we ring the bell Opening Day.”

The above was Casey’s response to Lindsey Nelson’s query, posed during Channel 9’s season preview show, “Now what about third base?”

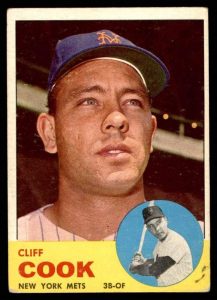

There’s no denying it’s better to win, six to five, than it is to lose, five to four. Alas, by the time the Mets achieved their initial 6-5 victory, over the Cubs in thirteen innings on May 15, Don Zimmer was no longer the Mets third baseman. Casey started Zim the first nine games of the year, all of them losses. Don’s batting average slipped below .100, part of an 0-for-34 skid that cost him his starting assignment as well as his roster spot. On May 6, the Mets traded Zimmer — a 1961 National League All-Star — to the defending NL champion Reds for Cliff Cook. Zimmer’s final totals as a Met: four hits, three errors and another fifty-plus years in baseball to exude that “spirit” even an .077 batting average couldn’t extinguish.

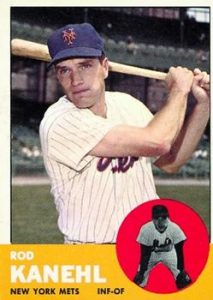

Cook was acquired to take Zimmer’s place at third base and, if the position wasn’t to his liking (or Cook wasn’t to the position’s liking), make a little history of his own as the first card-carrying member of the Mets OF-3B/3B-OF club. Let us distinguish card-carrying from those credentialed only by experience. The first third baseman-outfielder the Mets ever harbored was one of the signature players of their first team, Hot Rod Kanehl. The scrappy Mets utilityman who would create the template for all scrappy Mets utilitymen to come first played third base on April 21, in relief of Zimmer after a pair of pinch-hitting substitutions led to no runs, and then debuted in left field late in the April 29 doubleheader opener, a game the Mets were winning by eight runs after six innings. With Hot Rod showcasing his versatility, the Mets maintained their 8-0 lead and Al Jackson notched the very first shutout victory the Mets ever had

So why doesn’t Rod Kanehl rate a card for being a 3B-OF? Two reasons:

1) He was doing his utilityman job. Utilitymen who followed in Hot Rod’s fast footsteps — a cohort encompassing the likes of more than two dozen Mets spanning Rick Herrscher later in 1962 to Jack Reinheimer toward the end of 2018 — played third base and the outfield as asked because it’s what they were on hand to do. Teddy Martinez in the ’70s. Bob Bailor in the ’80s. Chico Walker in the ’90s. Heir to the Kanehl legacy Super Joe McEwing in the 2000s (“That was my life. That was my career. That was my job. I took extreme pride in that, being prepared for every situation,” McEwing told me in 2020 when I asked him about various facets of his utilitarianism.) You need a guy who can fill in at third base and somewhere within the outfield if you’re going to succeed. In 2016, the last year when the Mets made the postseason, the team had, depending on your yen for categorization, three or four of those guys: Eric Campbell; Kelly Johnson; Ty Kelly; and Matt Reynolds. The Mets’ recent signing of Reynolds to a Recidivist Met minor league deal may indicate, as much as the contracting of Escobar, Starling Marte, Mark Canha and Max Scherzer, that happy days will be here again soon.

2) I don’t issue the cards. Topps does. Several years ago, when I first began pursuing my OF-3B/3B-OF curiosity, I checked with Faith and Fear’s keeper of The Holy Books, my blog partner Jason Fry, and asked him to tell me how many among the thousand-plus Mets who had played as Mets to that point could claim Topps cards that identified them as Mets and labeled them as a third baseman-outfielder or outfielder-third baseman. Jason kindly perused his albums and answered me: four Mets as of 2016.

The first of them was Cliff Cook. His card is No. 566 in the 1963 set. He was a 3B-OF by Topps’s reckoning. That wasn’t necessarily the idea when he became a Met. After the Mets shipped Zimmer to Ohio and hoped for the best (not anticipating their hopes would be dashed by their new acquisition’s bad back), Cliff got his share of reps at third, starting 16 times in a 31-game span. He batted .216 as a third baseman, .208 overall. It was better than Zimmer. Low bar, but it was vaulted.

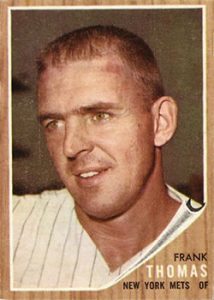

Even the 1962 Mets aspired higher from their hot corner and they looked up the line for their next solution. Left fielder Frank Thomas became third baseman Frank Thomas on June 17 against the Cubs, which meant third baseman Cliff Cook was almost simultaneously becoming right fielder Cliff Cook. The latter transformation impressed Topps more than it did the Mets, because by the latter half of July, New York’s Cliff Cook, who batted .207 in his new role, became Syracuse’s Cliff Cook. The Mets may not have been attached to their second 3B-OF — they gave up only an .077 hitter to get him — but Thomas was another matter.

Frank Thomas, flashing the power that would earn him 2022 induction into The Casey Stengel Vestibule of the New York Mets Hall of Fame, was already the Original Mets’ preeminent slugger, having knocked 13 homers over various walls in the Mets’ first 36 games. By comparison, Roger Maris had socked only eight balls out of yards after 36 games in 1961. Maris, en route to 61 home runs, mashed alongside Mickey Mantle, who would go on to 54. Stengel’s new kids in town didn’t have a companion slugger to take advantage of the Polo Grounds’ dimensions the way Thomas did, let alone the distances over fences elsewhere in the National League. As long as Thomas’s bat got its swings, maybe it didn’t matter where his glove wound up.

In the bottom of the first, following Thomas’s transformation into the first Met outfielder to become a Mets third baseman in the top of the frame, Lindsey Nelson broke the defensive decision down for Mets fans listening over WABC:

“And Frank Thomas is coming up, Frank Thomas, who is playing third base today in the lineup for the New York Mets. During his major league career, Frank Thomas has seen a great deal of action at third base. Pittsburgh Pirates used him there a great deal. Cincinnati Reds used him there. So this is not exactly a new position for him, though it’s the first time he’s played it for the New York Mets.”

Honestly, Lindsey seemed a little surprised that Thomas had been playing third for half-an-inning and maybe was trying to convince himself that this was a positive development. True enough, Thomas did have some experience at third base. As he told it in his 2005 memoir Kiss It Goodbye! The Frank Thomas Story, Frank’s first transition to third, in 1956, represented quite the to-do in Pittsburgh. The Pirates, for so long the doormat of the National League, had just moved into first place. Their stay was brief, but it was a much-needed jolt to the club’s self-esteem. Within two years, the Pirates would finish second in the NL, and two years after that win the pennant. Intrinsic to Pittsburgh’s rise was finding a full-time slot in the outfield for this kid the Buccos had drafted from Brooklyn following the 1954 season, a youngster named Roberto Clemente. Thomas, the everyday left fielder, essentially volunteered to break the logjam but removing himself from it.

One early June afternoon at Wrigley Field, “I played a position other than outfield for the first time in my career,” Thomas wrote, but the change didn’t come without warning. Manager Bobby Bragan had tried to persuade Frank to try third. The incumbent left fielder’s response: “At 320 feet out, I’m as close to those batters as I want to be.” Eventually, Bragan convinced Thomas he was natural born third base material. Frank had a knack for making barehanded catches (ask Willie Mays), and “anyone who can do that,” his manager told him, “is cut out to be a third baseman.”

Confident that his hitting wouldn’t suffer, Thomas agreed to try his hand — both of them — at third. Not only was a spot for Clemente opened up, but maybe a hole in the infield would be plugged. Presaging the situation that would surround him as a Met, Thomas recalled, “We had been having trouble all season finding a suitable third-sacker, and I was the tenth player to play there up to that point in the year,”. It was June 5, mind you. The Pirates even tried Clemente there once. “I was ready to make the switch if [Bragan] thought it would help the team.” In his memoir, Frank remembered the Pirates and himself playing well after he took on the new challenge, with none other than one of the all-time third base greats, Pittsburgh’s own Pie Traynor, going on local radio to praise his defense.

The record indicates third base may not have been Frank’s forte, certainly not upon manning a brand new position. Despite not taking over third until the season was more than forty games old, Thomas finished second in the National League in most errors committed by a third baseman. Somewhat established at the hot corner, he led the circuit in that dubious department in 1958. He could still hit, though, with 35 homers in ’58 forgiving his 29 miscues. After the Mets arranged to acquire Frank from Milwaukee, Stengel was happy to ink him into his batting order — and plant him in left field. With the 1961 Braves, who had Eddie Mathews, Thomas didn’t play third at all.

But this was 1962 and these were the Mets and best laid plans rarely remained undisturbed. Prior to June 17, the Mets had employed five different third basemen. Not ’56 Pirates-level, but close enough. Also, unlike in 1956, Thomas wasn’t concerned with his fielding getting in the way of his hitting. The man who’d go on to set the franchise’s single-season standard for home runs was wandering through a power desert, going homerless since May 25 and losing more than 40 points off his batting average in the process. And there was a personnel glut unfolding in the Met outfield, with the club having just acquired an old Stengel favorite, Gene Woodling, who, unlike Clemente in Pittsburgh six years before, was at the end of the line, but he needed a place to play regardless.

Around this time, Joe King offered several observations in The Sporting News that seemed to capture the plight of the Mets in their third month, when neither a stop in Texas to take on their fellow expansioneers the Colt .45s nor a taste of home cooking could rouse them from their recent losing ways.:

• “Casey had hitting for a few weeks, but Frank Thomas recently went 22 games without a homer and team run production sagged woefully.”

• “Then there was a time when Stengel felt that he had achieved a reliable, although modest defense. The Mets were not kicking the ball around at the start. This, too, was an illusion. The fielding crackup commenced in the finale at Houston and continued as the June home stand opened.”

• “No one summed it up better than Stengel: ‘I tell myself that it can’t be getting any worse, but it is.’”

• “If the Mets had a crew of kids with a year’s experience in the minors, it might be refreshing to play ’em for the remainder of the season. However, they do not have the men to achieve this renovation.”

And, the kicker:

• “Cliff Cook developed a strikeout seizure on the trip.”

So why not ask Frank to dig his third baseman’s glove out of storage? The man himself was willing and got himself ready. “To come in and play the infield,” he told the Crane Pool Forum in 2005, “you have to learn a lot of new things. I used to take 150 ground balls a day in order to improve myself there, and for the most part I feel like I did a good job.” In the first game the Mets put Thomas at third, he handled everything hit at him. Here’s Ralph Kiner describing all of it:

“Lefthander with a curveball, it’s hit down to third base. Frank Thomas there, up with it, over to first base in time for out number two. Frank Thomas, handling his first chance successfully at third base. Gene Woodling was put in left field, and Casey Stengel, in order to get more power in the lineup, moved Frank into third. He has played there before. He was originally converted to third base while playing for the Pittsburgh Pirates.”

Ralph sounded less incredulous about the switch than Lindsey had. Perhaps it was an ex-Pirate thing. Either way, that third-inning grounder Ron Santo hit to Thomas was it for third base opportunities in that June 17 doubleheader opener. If it didn’t go down as a momentous moment in early New York Mets history, it might be because it was a wee bit overshadowed by a couple of other developments that occurred in the same game. Lou Brock, then a Cub center fielder one day from turning 23 years old, launched a home run to the center field bleachers at the Polo Grounds. You may have heard about it from the oft-asked trivia question that has a pretty brief answer. Hardly anybody had ever gone that deep in that ballpark, nearly 500 feet from home plate. Those bleachers might as well have been in Yankee Stadium, across the Harlem River. But Brock reached them on June 17, 1962. As did Hank Aaron for the Milwaukee Braves on June 18, 1962. Before such a thing as Met opponents existed, only two players — Joe Adcock and Luke Easter — had done it. Now it had been done twice in two days.

While this was a noteworthy baseball achievement, that’s not the main reason the opening game of the June 17, 1962, resonates in Met annals. No, we remember that particular date because it was the day Marv Throneberry tripled in two runs off Cubs starter Glen Hobbie only to be told he hadn’t tripled at all because he hadn’t touched first base (or second) on his way to third. When one of your announcers — Nelson — has reason to inform you, “Hobbie comes off the rubber and throws over to first base,” leaving umpire Dusty Boggess no choice but to call Marv “OUT at first base on an appeal play!” and your momentarily heroic baserunner has to trot off of third and back to the dugout, you tend to forget everything else that happened.

The Mets lost, 8-7. Frank Thomas also started at third base in the nightcap, with Cliff Cook in right field. Thomas made an error that led to an unearned run in a game the Mets lost, 4-3. Frank started the next three games after that at third. After those five in a row, he’d be back in left field mostly, at first base occasionally, with only five more starts at third, none after July 8. His homerless drought ended in late June. Frank would finish the season with 34 longballs, most in a Mets campaign by anybody until Dave Kingman came along in 1975. The record also shows four errors in ten games at third base in 1962, plus one in one game when he played two innings at third in 1963, a year the Mets would be on to their next evanescent OF-3B solution.

In the next installment of OF-3B/3B-OF, we meet the next outfielder who wasn’t the answer at third; the next third baseman who carries a card that said he could play the outfield; and the youngster who preferred not to be blessed with versatility.

THE METS OF-3B/3B-OF CLUB

Founding Members (1962)

1. Rod Kanehl

Mets 3B Debut: April 21, 1962

Mets LF Debut: April 29, 1962 (Game 1)

2. Frank Thomas

Mets LF Debut: April 11, 1962

Mets 3B Debut: June 17, 1962 (Game 1)

3. Cliff Cook

Mets 3B Debut: May 8, 1962

Mets RF Debut: June 17, 1962 (Game 2)

4. Rick Herrscher

Mets 3B Debut: August 2, 1962

Mets RF Debut: August 7, 1962

“Brock reached them on June 17, 1962. As did Hank Aaron for the Milwaukee Braves on June 18,1962. Now it had been done twice in two days.”

Now, I always thought this was a great achievement, but I did not know it was twice in 2 days. That, and the fact that a beanpole like Brock could do it, leads me to believe that the windgusts were blowing out as fast as Brock’s speed!

I’m old enough to remember those “halcyon” days when the Mets had more third basemen than Zsa Zsa Gabor had husbands. “Sports Illustrated” had a pretty good table top baseball game, beginning in 1970. My younger brother bought the game for me as a Christmas gift that year. In addition, to the numbers for the pitchers and hitters, SI included comments on each of the 1970 MLB teams. For the Mets, one comment read, “The Mets brought in Joe Foy from the Royals to fill the gap at third and Foy created a chasm there.”

I don’t recall what SI said about the late Jim Fregosi as the Mets’ third baseman after the 1972 season, but it couldn’t have been fulsome in its “praise” for the former California Angel all-star shortstop turned abysmal hot corner flop at Shea Stadium.

Which brings me to the 2022 Mets; I hope like heck that J.D. Davis is NOT the Mets’ opening day third baseman, J.D.’s like the “Dr. Strangeglove aod Third Basemen.” Besides, he’s another reminder of the failed Brodie Van Wagenen regime. So I hope Davis is sent out of town like Juan Samuel and Roberto Alomar were.

Funny how all the Mets “Who’s on Third?” jokes stopped happening upon the arrivals of Messrs. Alfonzo, Ventura, and (especially) Wright. Now we’re back to square one (see: Davis, J.D.), but the Mets have certainly redeemed themselves from their early-’70’s Foy-bles.