Look at Dan Napoleon

And you might notice

The last name’s the first name

Just like Amos Otis

Like Ed Charles, Frank Thomas

Charlie Neal

Or Kevin Mitchell

But not Rod Kanehl

—Dick McCormack

On May 11, 1969, the New York Mets woke up in as good a situation as they’d ever enjoyed after 28 games: 13-15, a mark they’d reached previously only in 1963, good for third place in the newly carved National League East. Tom Seaver had just beaten the Astros, 3-1, to raise his record to 4-2 and lower his ERA to 2.08. Cleon Jones, having smacked his fifth homer of the young season, lifted his batting average to .402. Historically speaking, even without the benefit of 1969 hindsight soon to come, things were unquestionably looking up.

Yet to Red Foley in the Daily News, not much had changed since 1962. In that Sunday morning’s edition, Foley dwelled on the one constant that hadn’t budged since the Mets’ founding. They were still sorting through third basemen. “For the Mets, who’ve gone from A to Z trying to populate it,” Foley wrote, “third base has been a headache, the kind for which the boys at Excedrin don’t even have a number.”

If you watched enough television in the late 1960s, you got the reference. If you’d watched the Mets during their first decade, you understood the malady Foley was diagnosing. “If there’s a bromide for this lingering cranial pain,” Red elaborated, “you can bet your aspirin that managers Casey Stengel, Wes Westrum and Gil Hodges haven’t heard of it. They’ve tried a total of 40 brands and haven’t gotten to first base, let alone third, in the antidote league.”

Foley went on to giddily list all of the remedies that had purportedly failed, from “that memorable spring evening in St. Louis, when Don Zimmer became the foundation sire for the lengthening line of Met third basemen,” through all those “third basemen who conjure thoughts of those past days and nights when the Mets celebrated rainouts as moral victories” and up to the quartet that had thus far attempted to man third in ’69. “Now,” Foley concluded without giving an inch to the possibility that things maybe were turning a corner, “seven years and 1,163 games after Zim launched the hot corner odyssey, Rusty Garrett, Ed Charles, Amos Otis and Kevin Collins are helping extend the string that for too many has stretched from here to oblivion.”

Forty third basemen in just over seven seasons? Yikes! That sounds like a lot! But was it? Or was it just one of those Met myths that took hold in the earliest days and couldn’t be shaken? Thanks to Baseball-Reference, we can do some comparison shopping. Between 1962 and 1968, spanning all those tenth- and ninth-place finishes, here are how many third basemen each National League franchise employed.

Cubs: 14

Cardinals: 14

Giants: 16

Reds: 17

Pirates: 17

Phillies: 21

Braves: 22

Astros: 27

Dodgers: 27

Mets: 39…with 1969 rookie “Rusty” Garrett (also known as Red, more commonly as Wayne) making it 40

So yeah, the Mets used a lot of third basemen. Certainly a lot more than everybody else. A few amid those growing-pains campaigns were bound to wander in from the outfield.

Maybe Casey missed the best the Mets’ first Felix had to offer. According to Mantilla, the legend of the manager maybe not keeping both eyes on every game was more than myth. “People used to ask me if Casey Stengel used to go sleep in the dugout,” the 1961 expansion draftee told journalist Danny Torres in 2019, “and I said that was the truth.” One day versus the Phillies at the Polo Grounds, Mantilla swore innings one through seven went blank on Casey’s scorecard: “The guy was taking a big-time snooze […] God’s truth.”

It’s probably also true that anyone paid to watch the 1962 Mets every night and day might need to briefly escape to dreamland now and then.

However groggily decisions might have been made sometimes, Casey didn’t fully shut his eyes on what Felix — a man of “lusty good humor” in Vecsey’s estimation — could give him. After the Mets altogether gave up on Zimmer by trading him for Cliff Cook; after Stengel gave up on Cliff Cook by replacing him at third with Frank Thomas; and after Stengel gave up on Thomas as a third baseman and sent Frank back to left field, the manager turned again to Felix Mantilla. Nine Mets in all played third base in 1962. Mantilla was as close to a regular occupant of the Hot Corner as the club could claim. He put in 95 games at third, starting 88 of them and gave the Mets 141 games of baseball in all. The Opening Night shortstop in St. Louis settled in at third as well could be expected, finishing with a solid batting average of .275 and rating sixth among third basemen in double plays turned. It’s an esoteric stat, but considering 120 games were lost, it has to represent a feather in the 1962 Mets’ cap.

At bat, Mantilla was “drilling line drives in every direction,” Vecsey wrote, “but his fielding was a problem. Mets fans liked to imitate him, crouching forward, then rocking back on their hells, waving their left hands casually at the imagined baseball. That was Mantilla playing a hard grounder.”

Perhaps Mantilla, the first Puerto-Rican Met (more than a decade before kids coming upon his name in book’s like Vecsey’s did a double-take and thought, “doesn’t he mean Felix Millan?”) could have found his third base groove and slowed the door already revolving at the position had his services been retained for 1963, but Felix’s strong bat represented enough of a trade chip to land three players from the Red Sox in December of ’62: Tracy Stallard, Al Moran and Pumpsie Green. Two, Moran and Green, were about to become Mets third basemen. But neither was sent to play the outfield. Here in the land of OF-3B/3B-OF, that disqualifies us from saying much more about them.

As we roll like a 38-hopper into the second part of our series on players maybe not playing the position for which they were best suited, we’ve already said more than we planned about Mantilla, who somehow never played outfield as a Met despite seeing 155 games’ worth of action between left, center and right as a Brave, a Red Sock and an Astro in a career that lasted until 1966. He earned a World Series ring for Milwaukee four years before becoming a Met and made the AL All-Star team three years after leaving the Mets. “Mantilla,” Lenny Shecter wrote in his own fond post-1969 look back at the newly crowned champs’ humble beginnings Once Upon the Polo Grounds, “told the world that leaving the Mets was like being ‘pardoned from the electric chair’. He also said that the Mets were the worst team he had ever played on,” professionally or otherwise.

“He may have been right,” Shecter allowed, “but one of the reasons they were so bad was the way Felix Mantilla played the infield.” And Shecter may have been right, but Mantilla, the second player the Mets ever sent up to bat, turned 87 last July. That one year in New York losing all those games certainly didn’t kill him. Perhaps it made him stronger.

Not much strengthened the Mets as they entered their second season, and the third base door continued to spin. Charlie Neal, the primary second baseman from ’62, was tabbed to open the franchise’s sophomore season at third. He didn’t last there or at the Polo Grounds (like Zimmer the year before, he was traded to Cincinnati). Ted Schreiber became the tenth third baseman in Mets history as the Mets were losing their 125th game ever — falling to 0-5 en route to starting 1963 0-8. Ted’s Met highlight would come at year’s end when he grounded into the double play that ended the final National League baseball game the Polo Grounds ever hosted. In between, he’d conclude, “Casey didn’t want me.”

Chico Fernandez, acquired from Milwaukee in May, gave third a brief whirl. Larry Burright put in one inning at third, though Burright admitted in an interview many years later that “I’d never played third base before,” but Casey asked him to, so he tried it (after which, Casey told him, “go pinch-hit for Snider,” despite Burright already being in the game). Moran, mostly a shortstop, had his 3B cameo in May, the same week Ron Hunt commenced to moonlight at third. Hunt’s bright future, however, was mainly at second.

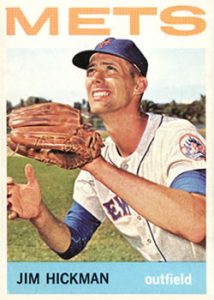

When the Mets chose Jim Hickman in the expansion draft, he had just completed a six-season hitch in the Cardinal chain. From 1957 through 1961, he’d played nothing but the outfield. When he made his major league defensive debut on April 14, 1962, it was in center. Because Opening Night CF Richie Ashburn’s wheels had only so much tread left on them, it would be Hickman who would eventually emerge as the closest thing Stengel could call an everyday starting center fielder. By Baseball-Reference’s reckoning, at no point in the minors nor in the majors entering 1963 had Hickman played third base.

So why not try him there? What did the Mets have to lose? More games? Please. The Mets were 25-42 on June 19 when the OF was first shifted for a couple of frames to 3B. As for Hickman, he was still pretty young (27) and still pretty promising (13 home runs in 1962) if not yet fully formed. Jim led ’62 team with 96 strikeouts, too many of them of the called variety for his manager’s liking. “Oh, you can’t improve your average,” Stengel felt compelled to remind him via ditty (per Vecsey), “with your bat upon your shoulder.”

The Mets improving their record with Hickman upon third base became the idea of the month after the Tennessean tested out the left side of the infield during an in-season exhibition versus their top farm club. “I know some of our players were a little afraid they were going to be left in Buffalo,” Casey cracked about the trip to the shores of Lake Erie. The stopover wasn’t only about maintaining healthy minor league relations and stoking major leaguers’ anxieties. Dana Mozely reported for the Daily News that Hickman “handled everything that came near him flawlessly and revealed a super arm. Everything he threw was a swift strike.”

Mozely may have been breathless in his assessment, but Stengel was circumspect. “I’ll think it out,” Casey said. “I’ve got to try ways to get more long-distance hitting in our lineup. Putting Hickman at third might help. Of course, we don’t know yet how he’ll do when they put on the bat play.” Either “the bat play” has since gone out of style, or Stengel actually said “the bunt play” (time spent with a Newspapers.com subscription indicates Daily News typographers of the day would have fit right in with the 1963 Mets’ defense).

When Stengel became game, Hickman had little choice but to do the same. A stiff upper lip went hand-in-glove with where he was taking his leather. The center fielder from April and May, who detoured to left and right much of June, got his first start at third on July 7. A month later, after he’d produced the first cycle in Mets history, he answered in the affirmative when Newsday’s Stan Isaacs asked him if playing third base was making him a better hitter.

“Well,” Jim reasoned, “I have been hitting a lot better in the last couple of weeks. I like third base. It [doesn’t] seem like I get as tired as I do playing the outfield. What takes it out of me in the outfield isn’t the playing, but the running back and forth between innings.” Stengel more or less shook his head at his OF-3B’s thought process: “He wasn’t tired when he knocked in all those runs earlier in the year.” But the Ol’ Perfesser theorized that if Hickman learned to properly shift his feet in the batter’s box, “he can make a living here as a third baseman. We been looking for a third baseman who can hit .260 and knock in 75 runs.”

Roger Craig was looking for anybody at any position to get him a big hit, and two days after Jim singled, doubled, tripled and homered in support of Tracy Stallard, Hickman did his ace pitcher teammate a solid. Craig was riding an eighteen-game losing streak. Good-luck totems fans sent him didn’t help. Counterintuitively switching his uniform number to 13 didn’t help. What — or who — helped was third baseman Jim Hickman lofting a walkoff home run to deliver Craig from a nineteenth consecutive loss. No 3-20 pitcher was ever so happy.

“The first thing I had in mind,” Craig said, “was to make sure he touched home plate. I’d have tackled him to make him do it if I had to.”

Over time, you likely would have had to have tackled Jim Hickman to keep him at third base when the Mets were in the field. Despite his brave words to Isaacs, he wasn’t really cut out to play third, possibly because he was an outfielder. “There are often drawbacks to that type of scenario,” none other than Frank Thomas averred in 2005 when asked to remember his and Hickman’s attempts to convert from the outfield. The numbers Casey wanted out of Jim weren’t there in 1963, with a .229 average and 51 RBIs his final totals. No Met homered more (17), but no Met struck out more (120). Despite not being sent to third regularly until July, Jim made the sixth-most errors in the National League at the position (though, like Mantilla in ’62, he ranked among the league leaders in double plays turned by a third baseman, which perhaps will happen when you play for a team that allows more than its share of baserunners).

More than four decades after Jim Hickman gave third base his best shot, he remembered for Bill Ryczek in The Amazin’ Mets, 1962-1969 that “they stuck me over there and it was tough. Heck, I was half scared to death. I wasn’t a natural third baseman and I just didn’t know what to do over there.” By Spring Training of 1964, Frank Thomas was again being talked up in the papers for third base and Pumpsie Green was getting a long look of his own. Jim moved back to the outfield as the Mets moved into Shea Stadium, and except for occasionally filling in, was done as a third baseman. Before he’d be done as a Met, he’d pile up the most home runs and runs batted in in Mets history — 60 and 210, respectively, over the franchise’s first five seasons, preceding his trade to Los Angeles.

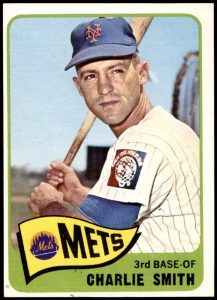

The man was a pro on a team often accused of being stocked with amateurs. In 1964, Charley socked twenty homers, the most by a Met since Thomas in ’62 (and the most until Tommie Agee in 1969). He also surpassed Hickman for the team strikeout lead and placed fourth in the NL in 3B errors. “Streaky” was how Vecsey described him, and it couldn’t have been surprising that, after hitting fewer homers and striking out even more (123 times) in ’65, Smith would be sent to his fifth club. Charley’s Met legacy, for our purposes, was Topps initiating him as a card-carrying member of the 3B-OF club in 1965. Charley played left field thirteen times in 1964; he played short in seventeen games. Maybe the Topps photographer dropped by Shea on one of those relatively rare LF instances and made sure to tell somebody back at the office that a “3rd BASE-OF” designation was in order. However it happened, Topps didn’t bother to print Smith’s first name in line with his preference. They had him as “Charlie” (then again, this is the same company that kept labeling Roberto Clemente “Bob”).

Smith was traded after the ’65 season with Al Jackson to the Cards for the quintessential “real” third baseman: Ken Boyer, barely a season removed from his MVP campaign for the ’64 Cardinals and with five Gold Gloves in his trophy case. Boyer, 34, was the essence of an accomplished veteran…which basically meant he was old, or at least baseball old. “Shopworn” was Vecsey’s descriptor. The Mets had gone the accomplished veteran route plenty since their founding. This is not to say Ken didn’t give the Mets an honorable year-and-a-half. In 1966, only Ron Santo made more assists among NL third basemen. Maybe the most valuable element Boyer gave the Mets was stability. For the first time, the Mets had a third baseman who finished in the top five in games played at the position…and for the first time, the Mets finished in a place above tenth.

The smattering of accomplished veterans the Mets brought in elevated the Mets to ninth place, but they weren’t long-term solutions. Neither, come to think of it, was the manager who steered them out of the basement. Wes Westrum had replaced Casey Stengel in the summer of ’65 after one of Casey’s 75-year-old hips gave out. Westrum went from interim to permanent to resigned in a little over two years. By the time Boyer was traded to the White Sox on July 22, 1967— and despite both Smith and Boyer having lent third base a hint of dependability for more than three seasons — the all-time meter on Met third basemen was up to 34. Before 1967 ended, by which time Salty Parker briefly replaced Westrum in the dugout and Gil Hodges could be heard driving up from Washington, the count had reached 38. Thirteen of those fellows had also seen outfield action as Mets.

The thirteenth among them would go down as the most misassigned Mets OF-3B yet…and probably ever.

Who’da thunk it? Probably not anybody who’d been watching the Mets for the seven seasons prior to Spring Training of 1969, not even the positive-thinking Hodges. Before it became clear Charles had a year of sheer poetry left in him and that 21-year-old Garrett might be more than prosaic in alternating with the 36-year-old, the Mets thought deeply of turning to another youngster to fill what was still considered their lingering hole.

Meet Amos Otis, the product of what could have gone down as one of the best moves the Mets ever made. On November 29, 1966, the Mets casually plucked young Otis, then a lad of 19, from the Red Sox farm system in the minor league draft. Much as the Orioles took Paul Blair from the Mets in the 1962 draft of first-year pros and then made the Mets regret the oversight while Blair piled up Gold Gloves and postseason appearances, the Mets could have filled the Red Sox with remorse.

In high school, Otis — who like Cleon Jones and Tommie Agee hailed from Mobile, Ala. — had played every position (“I was a jack-of-all-trades”), but primarily shortstop. For the Red Sox, he was tried at first, third, short along with the outfield. As a Met callup late in ’67, he’d get a fleeting glance at third, six days after Joe Moock got his. By 1968, at Triple-A Jacksonville, the Mets used Otis mostly as their center fielder. He flourished in all facets of his game, batting .286, swatting fifteen homers and stealing twenty-one bases.

By the spring of 1969, the Mets were committed to Agee as their center fielder. Agee endured a seasonlong slump in ’68, but Hodges believed in him, so much so that he vehemently disagreed with player personnel director Whitey Herzog’s brainstorm that Agee should move to right to clear space for Otis in center. “Jim McAndrew recalled that was the only time he ever saw Hodges and Herzog argue,” Mort Zachter noted in Gil Hodges: A Hall of Fame Life.

What Hodges believed about Otis, who’d earned All-Star accolades in the previous fall’s Florida Instructional League, was that the youngster could become the third baseman that would hush Red Foley and his army of skeptics. Not necessarily on board with the plan? Otis himself. When asked during Spring Training what was giving him trouble as he tried to learn third, this kid didn’t kid around: “Everything.” The player reasoned the Mets “made me an outfielder. They thought with my speed I’d be more of an asset in the outfield.” Then again, as Jack Lang pointed out in the Sporting News, Hodges was “up to his elbows in outfielders,” with Jones, Agee and Ron Swoboda each already penciled in as starters in March.

Amos Otis with fellow Mobile major leaguers Tommie Aaron, Cleon Jones and Tommie Agee. If only the kid could have stayed in the Shea picture.

Otis’s talent, minor league track record and assumed potential at more than one position attracted outside interest. The Braves dangled veteran catcher Joe Torre, a New Yorker with the kind of heavy bat the Mets were always lacking. Atlanta asked for a package of Nolan Ryan, Jerry Grote and Otis. GM Johnny Murphy demurred. “Otis,” he said, “is one of our untouchables.”

The response led to a bit of snickering that the Mets, whose 89-loss campaign in ’68 represented their high point to date, had untouchables — plural — but management sensed all that Youth of America the organization had been developing with a straight face since the days of Stengel was on the verge of paying off. And 1969 was about to prove them right.

But wrong about third baseman Amos Otis, at least when it came to what to do about him in the immediate future. Hodges carried the rookie north and started him three times in a row in April at third base. Dick Young snarked he was “the untouchable who finally became playable”. In what amounted to an abbreviated audition, Otis handled seven chances, made one errant throw to first, was credited with three assists…and then never again saw third base, except as an infrequent baserunner. “Third base,” Young concluded from scant evidence, “was strange for him.”

Amos received less and less playing time anywhere as the season wore on, fading from Hodges’s plans as the Mets otherwise shocked baseball with eptitude and competence. His average fell below .200 by mid-June, at which point he became the odd man out to make room for Donn Clendenon, acquired from Montreal for four Youths of America now deemed expendable; one of them was now erstwhile Met third baseman Kevin Collins. Otis spent the summer at Tidewater (batting .327), and wasn’t recalled until September, by which time his status as an extra outfielder was hardly a matter of primary concern for a band of miracle workers headed for the playoffs.

Garrett had a huge NLCS to help secure the pennant. Charles was the sparkplug of what proved the winning rally in Game Two of the World Series. Neither had posted dynamite numbers during the regular season — neither of them hit as high as .220 — but they were sure-handed enough, steady enough and ultimately the epitome of clutch. Just as nobody saw the Mets going all the way months earlier, it would have been tough to guess that the minor leaguer the Braves gave away and the old man who was viewed as hanging on would meld into the answer at third base for a team that never had an answer at third base.

Old habits, however, died hard. The world champion New York Mets, wrote Leonard Koppett in the revised version of his essential team history The New York Mets, still weren’t satisfied: “There just didn’t seem to be much future in filling third base with a Garrett-Charles platoon.” They released Charles. They invested minimal faith in Garrett. And they traded Amos Otis for Joe Foy.

Foy won a pennant with the Red Sox in 1967 and led the expansion Royals in RBIs in 1969. Kansas City nonetheless decided he wasn’t a building block, just as the Mets had deemed Otis a replaceable part. The Mets wanted an experienced third baseman who could hit and the Royals salivated at tapping Otis’s potential. Some deals prove win-win. This wasn’t one of those deals. Save for a 5-for-5 afternoon in San Francisco that he capped off with a tenth-inning, game-winning home run, Foy fizzled miserably for New York. Joe would be gone from the Mets following 1970.

Otis would make an impression in his new home right away and stick around for a very long time. “Incredibly underrated, and accomplished in all facets of the game: hitting, baserunning, and fielding,” Rob Neyer, a Royals fan from childhood, wrote in 2003’s Big Book of Baseball Lineups of the man who came to be known affectionately in K.C. as A.O. He made the American League All-Star team in his first Missouri summer, tipping his cap at the same Midsummer Classic as none other than Jim Hickman, who’d been reborn splitting time between left and right field for the Cubs when not spelling aging Ernie Banks at first. In the twelfth inning, it was Hickman who singled to center with Pete Rose on second, and it was Otis who fired home to Ray Fosse, only to see his throw rendered immaterial once Rose barreled over the catcher. The play is remembered for the baserunner and the backstop, but it was two Mets third base refugees who put the action in motion. After leaving the Mets, they’d each been stationed where they could be most comfortable and they had reached the spotlight, having succeeded at the sport’s highest level.

For Hickman, 1970 was the high point of a big league tour that wound through 1974. “Hickman was a youngster with a lot of potential in 1962, and he did a good job for us in the outfield,” Frank Thomas reflected in 2005. “He struck out a lot and made occasional errors in the field for which the fans sometimes got on him, so it was tough on Jim because he was only 25 or so years old. Casey tried to nudge him to improve with not-so-subtle hints in the dugout, and it would get to Jim, but Casey was just trying to help him develop. I think Casey’s methodology eventually got through to Jim because he went on to a nice career.”

Gil Hodges and Casey Stengel didn’t seem much alike, but Hodges, too, had great success getting through to the players he managed. The 1969 world championship and the testimonials that have rung through the corridors of time tell us Gil, in his quiet way, was a master communicator. Otis, though, was immune to Hodges’s motivational methods, however they manifested themselves. After Hodges, as manager of the National League All-Stars in 1970, crossed paths with Otis and extended his best wishes, Otis remarked, “That was half as much as he talked to me during my whole time with the Mets last year.”

No longer asked to play a defensive position outside the outfield, Otis lasted with the Royals through 1983 and then played part of another year for Pittsburgh. He made five All-Star teams, won three Gold Gloves, earned MVP votes in five separate seasons and went to the playoffs five times, thrice under Royals manager Herzog. He’d finish up with 2,020 hits, 193 homers and 341 steals. Bill James, a Royals fan before taking a front office job with the Red Sox, rated Amos Otis the No. 22 center fielder of all time in his 2001 Historical Baseball Abstract, terming him “strong, quick, fast, extremely graceful, and smart.”

Indeed, Otis was smart enough to wonder in an interview with Baseball Almanac in 2006, regarding his stint with the Mets, “I was one of the fastest players on the team, so why did they want to put me at third base?”

The Mets wouldn’t send one of their third basemen to the All-Star Game as a third baseman until nearly twenty years after Hickman and Otis first made it there as outfielders…and before long, they’d send that third baseman to the outfield. But that’s a ways off. In our next installment of OF-3B/3B-OF, we do meet a couple of other future All-Stars: the slugging outfielder whose awesome power was a fit in theory — but only in theory at third base; and another outfielder the Mets spent another spring pushing to third base only to have the outfielder push back.

THE METS OF-3B/3B-OF CLUB

The Ill-Advised Tradition Continues (1963-1969)

5. Jim Hickman

Mets CF Debut: April 14, 1962

Mets 3B Debut: June 19, 1963

6. Johnny Stephenson

Mets 3B Debut: April 26, 1964

Mets LF Debut: May 16, 1964

7. Charley Smith

Mets 3B Debut: April 24, 1964

Mets LF Debut: August 17, 1964

8. Danny Napoleon

Mets 3B Debut: April 24, 1965

Mets LF Debut: May 22, 1965

9. Chuck Hiller

Mets RF Debut: August 14, 1965

Mets 3B Debut: August 22, 1965 (Game 1)

10. Gary Kolb

Mets LF Debut: April 21, 1965

Mets 3B Debut: September 1, 1965 (Game 2)

11. Tommie Reynolds

Mets LF Debut: April 11, 1967

Mets 3B Debut: April 29, 1967

12. Phil Linz

Mets 3B Debut: July 19, 1967 (Game 1)

Mets LF Debut: August 8, 1967

13. Amos Otis

Mets 3B Debut: September 7, 1967

Mets CF Debut: September 8, 1967 (Game 2)

14. Jerry Buchek

Mets 3B Debut: April 23, 1967 (Game 2)

Mets LF Debut: June 11, 1968

Greg: THank you for quoting my 60s memories of the Mets.

Seems like yesterday. I knew those guys. One of them was the only MLB player who took me on the field during infield practice (remember infield practice?) The Mets were in the Astrodome in 1968 and I asked Ed Charles what it was like to play 3B on that rudimentary carpet, so during pre-game practice he grabbed somebody’s glove, told me to put it on, and escorted me to stand behind him at the “hot corner.” I saw balls skitter at odd angles and parabolas off the chemical lawn — for 5-10 minutes. Then he turned to me and shrugged, meaning, “Now you understand.” Nobody hauled me off, and he made sure I got back safely to the sidelines. A highlight of my career. We remained friends, were in touch to his final days, and I miss him….Suspended in the air over the pitching mound, at the end of the next season.

Kanehl is a constant in my emails with a teammate of his…and I remember Mantilla…and Charlie Neal….Danny Napoleon, great guy….clubhouse sages and wits.

Keep writing about the Mets. We might be dredging up these memories all summer long.

GV

Thank you for providing us with such rich detail, right up this moment, George. The Ed Charles tutorial is a blast to know about.

In that “hallowed pantheon” of truly lousy Met trades, the Amos Otis for Joe Foy trade is right “up there,” just behind the Nolan Ryan for Jim Fregosi trade and Tom Seaver to the Cincinnati Reds trade. What’s the next lousy Met trade: Scott Kazmir for Victor Zambrano, a/k/a Victor “Zamboozled” or Lenny Dykstra and Roger McDowell for Juan Samuel trade? (Some Mets fans might argue that it was the Jeff Kent and Jose Vizcaino trade for Carlos Baerga and Tim Foli lookalike Alvaro Espinoza of the Cleveland Guardians, formerly the Cleveland Indians.)

I remember when Ron Swoboda was filling in as guest host on John Sterling’s old sports talk show on either WMCA or WABC. A caller asked how could Met GM Bob Scheffing have ever traded Nolan Ryan for an over the hill player like Jim Fregosi. Ron Swoboda replied, “Bob Scheffing did not make that trade,” but declined to expand on that answer. I always wondered just who made that abysmal trade: M. Donald Grant, Gil Hodges? In Bill Madden’s book on the life of the late, great Tom Seaver, “Tom Seaver:A Terrific Life,” Madden quotes former Mets farm director Whitey Herzig as saying, “I wound’t have even traded Leroy Stanton (a throw-in in the Ryan/Fregosi trade) even-up for Jim Fregosi.”

So, I guess we’ll never know who was the “architect” of that Shea Stadium disaster. At least, neither Fred nor Jeff Wilpon can be blamed for that New York Mets colossal blunder.

I can’t believe you wrote about that today. Last night I watched ‘An Amazing Era” for the first time in at least 25 years .(Trying to get there new girlfriend to understand the Mets passion-they really need to update that video.) We were fixiated on how he rhymed all the names of the players to play 3rd base in the song. Tonight’s gonna be 86’s “A season to Remember.” On a side note with today’s news… Anyone remember the game I think it was the WhiteSox in 2013 that Harvey was pitching a no no for like 7 innings? Ironically, I think Gooden was there doing commentary that night but why I am bringing it up?? Harvey was bleeding from the nose while pitching. Who nose? Many times when i was younger and stupider my Kleenex looked like the flag of Japan in the morning and I told all it was the dry air…

Helluva night on the mound. Can’t vouch for what the rest of the pitcher’s night entailed.