It’s Sunday night. The Mets haven’t won in more than a week. As if that’s not enough of a shame, our greatest miracle has been celebrated anew, and this is how our team responds in the present? What we could really use is a nice offensive explosion while everything is looking listless and limp, maybe a five-run inning leading to an 8-5 slumpbusting win.

Eerie how history can rhyme sometime.

The parameters of the lede paragraph were all in place on this most recent Sunday night, but it was also the situation a little over three years ago. On June 30, 2019, the day after the Mets celebrated the 50th anniversary of the 1969 world championship, they were aching for a win following a loss in Chicago; four in Philadelphia; and two more at home to Atlanta. (They’d also inadvertently killed off two members of their first champions in a flub-flecked In Memoriam reel and had to walk back Jason Vargas’s threat of physical harm to a reporter.) The abyss-tumbling even started at Wrigley, just as it had this summer, though then there wasn’t an All-Star break to consume the middle portions of those 2019 doldrums. ESPN came calling, anyway, somehow thinking that those Mets were national-audienceworthy. The Mets, as if to make it up to their inconvenienced fans, handed out replica 1969 World Series rings to their earliest arrivers.

No chance loomed that the 2019 Mets would be enlisting jewelers to manufacture real things based on how the club kept playing through the middle of the eighth, trailing the dreaded Braves, 5-3. Yet there the Mets were, on the field, unaware their season was essentially over. And in the bottom of the eighth, there was a home run, a couple of other big hits, a three-run lead and, in the ninth, Edwin Diaz on to record three necessary outs.

On July 24, 2022, history chuckled at its rhyme. Well, I did. I was at that game three years ago, when, with the Mets mired in a seven-game losing streak and courting embarrassment everywhere they stepped, they snapped out of it. Todd Frazier led off that eighth with the precedent-setting homer and newly minted All-Stars Jeff McNeil and Pete Alonso delivered impactful blows themselves, each driving in a pair of runs. It was cathartic — because I could swear the Mets were never going to win again — and it was respectful. You don’t get swept by the Braves when you’re remembering 1969.

We couldn’t help but remember 1969 this Sunday three years later, not with Gil Hodges’s induction going final on the road in Cooperstown. You didn’t need to follow the out-of-town scoreboard to know it had happened. Thanks to ESPN’s machinations, the Mets’ first pitch was pushed to 7:08 PM, plenty of time to watch the immortality festivities. Usually I’d gripe at being subject to the indignities of Sunday Night Baseball. On this occasion, I was grateful for the lack of channel-changing. I could focus on Gil and every other honoree in the afternoon. I could worry about the Mets later.

When Gil was elected in December, I literally shed tears of joy. Then, when it was announced Buck O’Neil would be joining him, the parade of precipitation from my eyes intensified. No tarp was necessary. Let it rain. Baseball had waited too long to make things right. The wrongful drought was over. The eternity those who cared for Hodges, O’Neil and, for that matter, Minnie Miñoso, ended. Winter after winter, their families and fans searched for any clue that some committee would sign off on what so many baseball-lovers knew in their hearts, that these men were as worthy of recognition as any with whom they’d crossed paths or were denied access to competing against. The waits for Gil and Buck and Minnie made the Mets’ three-game losing streak versus the Cubs and Padres appear mighty inconsequential.

Not that losing three in a row (five, if you wish to punish yourself with the results of the Home Run Derby and All-Star Game) is a breeze. Nobody likes having to endure a staggering eight days between Met victories while the Mets sit mired in first place. Oh, the humanity. It was cause for dismay, perhaps discomfort, maybe a cue to press the silent alarm that sets off the panic button, but did you really think 2022 was all but over with more than two months remaining in the Triple Wild Card Era?

Don’t answer that question. I doubt I want to know.

Thank goodness that long, Metropolitan nightmare ended Sunday evening, mostly when the Mets poured five runs on the board in the sixth after doing nothing for the first five. Carlos Carrasco pitched credibly (he gave up nothing before exiting in favor of loosening Drew Smith’s arm) and Brandon Nimmo fielded wonderfully (he saved at least one run after Eric Hosmer unleashed his trademark awfulness on Smith in the form of an RBI double), but Met batting was merely for show. Not much of a show, either.

In the sixth, when I was ready to join the hordes believing the Mets would neither score nor win ever again, the 2022 team reminded us that they’re not too bad. Versus Joe Musgrove, Starling Marte walked, Francisco Lindor singled and that Alonso kid from three years ago blasted a home run that could have given Juan Soto a run for his Derby money, or any money awaiting Soto. Suddenly, the Mets had a 3-1 lead. Suddenly, a Met had gotten a big hit with runners on base. To quote Ben Fong-Torres in Almost Famous, “Crazy.”

Crazier, still, hustling Daniel Vogelbach crossed the plate for the first time as New York’s own, when a two-out Luis Guillorme fly ball to shallow left fell in front of a tentative Jurickson Profar. Vogelbach had walked, advanced to second on a friendly Mark Canha (possibly pronounced CAHN-ya) grounder and rumbled 180 feet as fast as he possibly could, presumably as fast as he grabbed the first flight out of spiritually eliminated Pittsburgh to join a pennant race. Then, as long as miracles were in the air, Tomás Nido, he of the perfectly reasonable “whaddaya mean Buck didn’t pinch-hit for Nido?” carping roughly 24 hours earlier, doubled home Guillorme.

It was 5-1 en route to 8-1 en route to 8-5 after the Mets had spent the week either trailing or idling. It was enough to allow for a bead of sweat to be dabbed from the forehead, even as the relievers meant to mop up spilled their soapy-water buckets. Newly assigned David Peterson gave up a run in the eighth and Joely Rodriguez…well, let’s just say he hasn’t been a Joely good fellow of late. In the ninth, the lefty less-than-specialist allowed four Padres to reach base and two of them to score without recording an out. Rodriguez wouldn’t see a fifth Padre. Instead, we’d see Diaz, and Diaz would see to the end of things, no discernible harm done.

Dab your forehead again. The Mets not only didn’t lose, but they increased their lead on the Braves back to a game-and-a-half, although you’re already sure the team that’s led the division without pause since the second week of April courts doom every instance it swings and misses. I’m susceptible to Last Thing I Saw Syndrome, too, and as I hadn’t seen a Mets win in two Saturdays by Sunday night, I was ready to surrender to my bleaker instincts when it was Padres 1 Mets 0 in the middle of the sixth, never believing it could be Mets More, Padres Less by the end of the ninth.

I wonder how I would have handled July heading into August of 1969 with that kind of attitude. I’d like to think my manager wouldn’t have allowed me to start thinking the worst.

The Mets of 53 summers ago actually sagged in the middle. Their dip amidst miraculous doings is usually handled in a lone anecdote. They were getting their posteriors whupped by the Houston Astros in a doubleheader at Shea on July 30; Cleon Jones looked slower than Daniel Vogelbach going after a ball; and Gil Hodges sternly walked to left field to simultaneously remove Cleon and send a message to his teammates. Soon after that, the Mets more or less took off toward their destiny. With their manager guiding them to a better attitude, nothing could stop them from reaching highest altitude.

Which sounds great, though from the doubleheader of July 30 up to Woodstock weekend, there came no sun for the Mets. It took the expansion Padres coming into town while Richie Havens and everybody else got playing in Bethel to lift the Mets from the mud. We were 9½ out as late as August 14; we concluded regular-season proceedings 8 up on October 2. And that was just the Miraculous appetizer.

But let’s not forget that sag. As my late friend Dana Brand put it in Mets Fan, following his reliving and reveling in the second-place Mets’ unlikely July triumphs over Leo Durocher’s first-place Cubs, “Then it all collapsed. It had to. How could it possibly have happened? How could we have dared to hope for this? By mid-August, after a rough month [… t]hey were in third place, as the Cardinals had finally woken up. And the Pirates were gaining. We would probably finish fourth. It was okay. This season had been more fun than any Mets season had ever been. I was crushed. I was only 14, but I knew something about how the world worked.”

I didn’t. I was 6. I was only waking up to the Mets that summer. I place the opening of my eyes as somewhere between Woodstock overwhelming the New York State Thruway and the LOOK WHO’S NO. 1 shoulder-tap on Shea’s massive scoreboard. I don’t remember anything specific before the Mets chasing down and passing the Cubs as first grade was starting. I didn’t know that the Mets had never won many games let alone any pennants before 1969. I just knew they were winning a bunch now; and everybody said it was “Amazin’” without irony; and I wanted to be a part of it; and that I never stopped being a part of it.

Somewhere in those first weeks of awareness, I came to know the name of the man who was steering the ship. It was Gil Hodges. I didn’t know about his platooning or his quiet leadership or his willingness to tell his best hitter, in so many words, maybe you ought not be out in the field if you can’t chase after a ball properly without making more of a scene out of it than he had to. I certainly didn’t know about the playing career that preceded his becoming manager of the Mets, or that it took place in Brooklyn, where my family lived before I was born, and that he and his team in that borough were glorious and that everybody revered Gil Hodges. The reverence I’d figure out by 1970. I was only 7, but I knew something about how the world worked.

Fast-forward, as one will, to the present, and there was Gil Hodges being inducted into the Hall of Fame. It had been talked about since he was still alive, which was a mighty long time ago. Gil began appearing on Hall of Fame ballots in the winter of 1969, before the season that would define him and the Mets and this Mets fan here. He didn’t make it the first time he appeared. Or the second time. Or the third time. There was enough time then for his young daughter Irene to ask her dad if he thought he’d ever go into the Hall of Fame.

“No. Never,” was Irene’s father’s emphatic reply. She asked why. “Those are all great players in there. I’m not even close,” was his humble explanation.

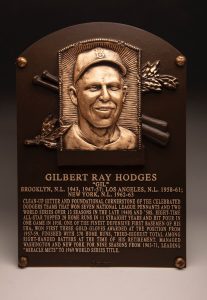

Forgive the heresy, but Gil Hodges was wrong. A lot of people continued to think he was wrong, and now there’s a plaque definitively refuting his self-assessment. Irene and her siblings were in Cooperstown Sunday to shepherd the plaque to its final station, in the Hall of Fame gallery. The daughter gave such a wonderful speech in honor of her father. As the son of a Brooklyn schoolgirl, I could hear the Brooklyn schoolgirl in Ms. Hodges throughout her presentation. She’d been assigned this report months ago by the Golden Era Committee’s vote, in her heart most of a lifetime ago, it is safe to infer. Just before she spoke, Tom Verducci on MLB Network explained how it came to be that Irene rather than brother Gil Jr. or sister Cindy gave the official address. Gil Jr. told Tom that Irene said, “Mine,” and that settled it.

Good a call as any if you saw it, and because the Mets didn’t play until Sunday night, you could see it live without conflicting interests. “Today,” Irene said as she wrapped up a review of her father’s career, life and the impact it had on others, “I am especially happy for my mother,” Joan Hodges, who was watching back home in Brooklyn because traveling is too much of a burden at her age. “When the call came from the Hall of Fame, and I heard, ‘this is Jane Forbes Clark, and it is my honor…’ I began sobbing probably as much as I did when I lost my father. I was so beyond happy for him, and even thrilled that my mom, at 95, and would be able to hear this news.” Irene was too much of a class act to note that had this decision been certified in a timelier fashion that her mom could have been in Cooperstown speaking herself. One assumes Irene had the value of grace instilled into her at an early age by both or her parents. Her father, after all, “would only do what he thought was the right thing. That was my dad.”

I thought it was telling that the four living 1969 Mets who made the not easy trip upstate to watch Irene Hodges accept on behalf of her dad were four Mets who could have spent the last fifty-plus years nursing grudges. Ed Kranepool lost playing time to Donn Clendenon after having been spotlighted as the Mets’ first homegrown star. Art Shamsky wasn’t the regular he looked forward to being when he was traded from Cincinnati. Ron Swoboda was prone to chafe at authority. And Cleon Jones was taken out of a game against Houston after not going hard after a batted ball, maybe because the Mets were getting blown out and it didn’t seem worth it or maybe, because Cleon says, his leg was bothering him and his manager recognized that. Yet each man won a championship by overcoming their initial differences with Gil Hodges and accepting the leadership Gil Hodges offered them and, literally to this day, each man will tell you the main reason they earned a ring that could be replicated as a promotional giveaway was mainly because of Gil Hodges. They have nothing to gain in 2022 by continuing to revere Gil Hodges. They do it because they think it’s the right thing.

In Flushing, in the aftermath of the Hall of Fame induction of the late Gil Hodges and six other worthy honorees (the late O’Neil, the late Miñoso, the late Bud Fowler, the advanced-aged Jim Kaat and Tony Oliva and the robust David Ortiz), the Mets gave out Gil Hodges bobbleheads to the first 25,000 through the gates at Citi Field. I imagine it complements the 1969 replica ring nicely for those who attended on both that Sunday night three years and this past Sunday night. In 1969, Gil called the likes of us who buy tickets and cheer our heads off “beautiful fans” for our support, given to his team that year all year, even in the middle of summer when they sagged.

I don’t know how beautiful we are on a given day in the midst of a given losing streak. I do know it’s beautiful that Gil is enshrined where he is enshrined.

EXCELLENT entry today!

Thank you.

Well, I also watched Gil Hodges daughter give that speech and I can tell you it was very wet here in North Hollywood–and NOT from any rain, (what’s that?) but from this 60-year long Met fan.

It’s about time–actually way past time for Gil-but to have Buck O’Neal & Minnie Miniso at the same!-what a bonus from the Baseball Gods!

Seeing Cleon & Ron Swoboda, Seaver’s daughter & Ed Kranepool just increased the water dripping here.

And I do recall that Mets game when they put up on the scoreboard at Shea-Look whos #1!

We’re number 1!

Let’s Go Mets for ever & ever!

Thank you Greg, well said. And while sure, it turned out to be convenient that the Mets got ESPN’d to the Sunday night schedule, there would have been no divided loyalty in my TV room. I can and do watch 162-ish Mets games every season; yesterday afternoon was the only time in my life I was going to get a chance to see Gil Hodges finally taking his place in Cooperstown, where he’s belonged for decades. Even a quiet but stern manager walking out to left field wasn’t going to drag me away from that.

All that remains is for Gil to be canonized by the Pope. The miracle attributable to him has been very well documented.

The Mets freezing 2 RISP LOB with 0 outs in the bottom of the 5th inning with 3 anemic unproductive groundouts, followed by Nimmo’s catch, followed by 2 RISP with 0 outs repeating in the bottom of the 6th, but this time the offense breaking out encapsulated the rush of being a sports fan.

Good 1st impression by Vogelbach. Montgomery, a lefty, starts for the Yankees tomorrow, but I wouldn’t mind seeing Vogelbach DH anyway. Maybe he’ll hit lefties as a Met.

Justice has been served,Gil is in! We got to converse with Gil’s 95 year old cousin from Indiana.The man arrived with his cane and told us WW2 stories of his own as well as Gilbert stories from back in their youth.What a family! Irene’s speech had us all in tears.The story about Gil not wanting to call his own mom(it was Joan’s idea) right after the Mets won in ’69 because Gil felt it wasn’t right to use the company phone for a long distance call says quite a lot about the man.He did everything right in his life.MLB dropped the ball waiting so long to let him in. Having the four men from that team,Gil’s daughter,Agee’s daughter and Seaver’s daughter in the same place made it all feel right.Justice has been served.We can all breath easier……Let’s Go Mets!

Great column. I’ve been waiting for this day and remembering my dad and his love of Brooklyn for a long time. I shook Gil’s hand at the 1962 Camera Day in the Polo Grounds. Haven’t washed it since :) I was lucky to be Vin Scully’s radio engineer and asked him all about Gil before airtime. I wore #14 at Mets Dream Week 2000, where my coach was Joe Pignatano. I talked to Campy once in Cooperstown too. So many loose ends neatly tied up in a perfect sentimental afternoon.

So happy for Gil’s family, as well as for me and all our brethren.

I sometimes drive by Gil and Joan’s house, where Joan still lives, hoping to get a glimpse of her royal highness, but so far, no luck.

And Gil is buried near where my Dad’s family is buried, at Holy Cross cemetery, so I make sure to always stop by and give my silent thanks for the Miracle.