“You’ll never get me to downgrade the Mets. They’re not the only last-place team I ever played for. The fans here are hard to beat. When I was in the hospital this season, I got 600 to 700 letters and cards. You can’t beat that.”

—Frank Thomas, 1964

When he debuted as a major leaguer, starting in center field for the Pittsburgh Pirates at Forbes Field on August 17, 1951, Ralph Kiner, who would begin to describe his feats over the air eleven years later, flanked him in left field, just another day at the office for the glamorous slugger en route to his fifth of seven straight National League home run crowns. Danny Murtaugh, who would manage him six years later and world champions twice, played second base down the middle in front of him. The Chicago Cubs, the team composing the other half of the 8/17/51 box score, was populated by names that more than 70 years later would make a hardcore baseball fan’s neck hair rise like it was hearing the first notes of the Star-Spangled Banner: next season’s MVP Hank Sauer; erstwhile Dodger World Series goat Mickey Owen; fellow Brooklyn castoff Gene Hermanski; all-time pinch-hitter Smoky Burgess; a then non-existent franchise’s first modern hitting coach Phil Cavaretta; TV’s eventual Rifleman Chuck Connors; a Turk (Lown); a Monk (Dubiel); and Eddie Miskis, of whom it would be written two decades hence that he was “the sort of guy that if you were introduced to him at a party and he told you he was a big league ballplayer, you’d think he was kidding.”

For real, though, they all roamed the earth and the section of Pittsburgh known as Oakland simultaneously, big league baseball players gathered for the entertainment or perhaps exasperation of 10,007 paying customers on a Friday night. The Cubs, in losing by five, fell to 50-62, remaining solidly in seventh place in the National League. The only team looking up at them in the standings was that evening’s 8-3 victor, the cellar-dwelling Buccos. Their record rose to 47-68. Their fortunes rose at least a little with the emergence of their fresh new center fielder, Frank Joseph Thomas.

By the end of the season, the Pirates would climb from eighth place to seventh, passing the Cubs. Thomas, Pittsburgh-raised himself, hit his first career home run on August 30, 1951, at the Polo Grounds in New York. The site of his initial slugging represents an epic piece of foreshadowing. New York and the Polo Grounds explain why we gather today to remember Frank Thomas, who died Monday at the age of 93, the oldest living Met at the time of his passing and, until January 16, 2023, the last surviving Met to have been born in the 1920s. There aren’t many Mets left who can claim substantial careers before the birth of the Mets. Thomas was always one of them.

The 1962 Mets would come later. The 1952 Pirates came first. Well, last. Whatever late-season progress Pittsburgh accomplished on the heels of Thomas’s promise and Kiner’s growing collection of home run crowns faded with the reality that the Pirates of those days were roughly the Mets of their day. Not the Mets we know today, but the Mets as they introduced themselves, which was when our fates intertwined indelibly with Frank’s. Because you might have listened to what Ralph Kiner had to say every year from 1962 through 2013, you know the 1952 Pirates led the league in losing. Losing like crazy: 42-112, 54½ games out of first, 22½ games out of next-to-last. You couldn’t blame Kiner — he was leading the NL in homers once more. You couldn’t blame Thomas, either. He was farmed out to New Orleans for all but a September cameo. Frank, turning 23 that summer, hit 35 home runs in the Southern Association. Kiner drilled into us Pirate GM Branch Rickey’s philosophy of negotiating with his star of stars: We finished last with you, we can finish last without you. Entering 1953, perhaps the Pirates realized to stop finishing last or right near it, they should promote Frank Thomas once and for all. Kiner would be traded in June. Thomas would stick around.

By 1958, Frank Thomas’s Pirates were a second-place ballclub, finishing 84-70. In terms of progression, it was a miracle of sorts. The Bucs hadn’t had a winning record since 1948. They’d had nothing close to a legitimate pennant contender since 1938. They hadn’t won a pennant since 1927. The contours of a champion are obvious in hindsight. The 1958 Pirates included Bill Mazeroski, Dick Groat, Roberto Clemente, Roy Face, Vernon Law and Bob Friend, to name a half-dozen distinguished members of the 1960 world champion Pittsburgh Pirates. But when it came to home runs (35) and RBIs (109), no one Pirate steered the ship in 1958 more than Frank Thomas, making his third NL All-Star team, finishing fourth in MVP voting — directly behind Ernie Banks, Willie Mays and Hank Aaron — and living the dream of a hometown boy leading the hometown ballclub toward glory just over the horizon.

Except when the Pirates reached the promised land in ’60, Thomas was, like so many of the balls he socked, long gone. Traded to the Reds ahead of the 1959 season. Traded to the Cubs ahead of the 1960 season. Traded to the Braves in the midst of the 1961 season. Then, to bring it around to where we come in, traded before 1962 began to a team beginning in 1962.

Move over 1952 Pirates. Meet the Original Mets. Meet the Original Frank Thomas. He embraced that nickname in retirement for several reasons:

1) Another Frank Thomas emerged in baseball much later, and it helped to clear up mistaken identity.

2) It was probably better than being called the Big Donkey, the nickname with which Thomas was saddled in his playing days.

3) He was very much an Original Met.

4) He was very much a Met original.

The original Frank Thomas was originally obtained by the Mets for a player to be named later. The most famous of PTBNL situations associated with the 1962 Mets — 2023 Met bullpen coach Dom Chiti’s dad Harry being traded, ultimately, for himself once the Mets sent the catcher back to Cleveland from when he came — overshadows the slightly off-kilter transaction that landed Frank on the Mets. The fledgling club had selected outfielder Gus Bell with their fourth pick in the 1961 expansion draft. Bell had played with Thomas in Pittsburgh in ’51 and ’52 before Pittsburgh traded Gus to the Reds and finished last a whole lot without him. Bell made four NL All-Star teams himself before doing bench duty for Cincinnati’s ’61 league champs. The Mets couldn’t wait to swoop him up and stick him in right field to commence their existence, which is to say on the other side of the outfield from Thomas in left.

A little over a month later, the Mets revealed Gus Bell, with thirty games already in the books, as the player to be named in order to acquire Thomas. Off Gus went as 1962’s revolving door spun without pause. By then, the Original Frank Thomas was a stalwart and staple of the big doings in Upper Manhattan. The Polo Grounds was not only home to the new club in town, it was a comfortable fit down the left field line for Thomas’s righthanded swing, as it had been in 1951. He had power for any park, but it didn’t hurt for a righty pull hitter to play where a homer could tuck around the left field foul pole some 279 feet from home plate. Of course if it was as simple as popping long fly balls just beyond the reach of frustrated left fielders, every Met would have done it.

Among 1962 Mets, only Frank Thomas hit home runs with what you’d call frequency. He hit 34 of them, more than twice as many as any other Met (Marv Throneberry, who is remembered as Marvelous for many reasons before you get to “second on team in homers with 16”). Frank walloped seven dingers in the season’s first three weeks, had thirteen to his credit before Memorial Day and, as August dawned, went on a tear yet to be matched in Met annals: two home runs in the game of August 1; two home runs in the game of August 2; two home runs in the game of August 3. For good measure, another home run in the second game of a doubleheader on August 4. When the season ended, Thomas’s total was sixth-best in the National League, trailing only those of five Hall of Famers (Mays, Aaron, Frank Robinson, Banks and Orlando Cepeda). He outslugged every player in the city of New York, which is to say Thomas’s 34 was better than the 33 posted by Roger Maris and the 30 off the bat of Mickey Mantle. One year after 1961, when the M&M Boys blasted 115 home runs between them for a team that won 109 games, this was no small feat. When you realize Thomas stood virtually all alone in a lineup destined to absorb 120 losses, it looks even bigger.

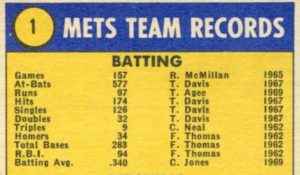

And when you’re a seven-year-old kid eight years later and you turn over Topps Card No. 1 for 1970, the team picture card labeled WORLD CHAMPIONS on the front, and scan the Mets’ various single-season records through 1969, you learn that F. Thomas and his 34 home runs are still the most home runs any Met has ever hit in one year, you can’t imagine any record any bigger within the realm of the team you have chosen as your own. No, you think to yourself, these Mets, defending WORLD CHAMPIONS or not, don’t really hit home runs. They wouldn’t in 1970 or 1971 or for a few more years and you just assumed Frank Thomas’s 34 from 1962 were unassailable. You knew Maris once hit 61 for the Yankees. You knew that a Willie Stargell might pound 48 for the Pirates or Johnny Bench might go deep 45 times for the Big Red Machine. You also knew no Met had ever hit more than 34 and took it on faith no Met might ever hit more than 34. You were OK with this because it was on the back of that baseball card. It was just a fact, and as facts went in a kid’s mind, it was king-size.

Then came Dave Kingman in 1975 and Kingman hit 36 home runs as a Met, and so much for 34 as the ceiling for Met sluggers. Kingman would hit 37 in 1976 and match it during his second Met go-round in 1982; and Darryl Strawberry would eclipse Kingman with 39 twice before the 1980s ended; and Todd Hundley would come along in 1996 and push the record all the way to 41, which Carlos Beltran would match in 2006; and Pete Alonso would shatter everything prior to his Polar Bear prowess when he hit 53 home runs in a Mets uniform in 2019; and through 2022, a Met has hit 34 home runs or more on 22 separate occasions.

Yet Frank Thomas’s 34 home runs is still the Mets record of the heart. A little piece of it, anyway. The rest of the back of that 1970 team card included year-by-year team records. That seven-year-old who pulled it from one of those tri-fold packs you could get at the Woolworth’s in the Green Acres mall learned quickly that his favorite team had never — never — been any good prior to 1969. They’d been particularly gruesome in 1962, yet here was one player, this F. Thomas, having hit more home runs than any Met ever had or presumably ever would. Who knew from Dave Kingman let alone Pete Alonso in 1970?

Funny thing is whenever old Pittsburgh Pirate hero Ralph Kiner or his broadcast partners Bob Murphy and Lindsey Nelson, or any of the writers who had covered the Mets continuously from 1962 into the 1970s, had reason to bring up the Original Frank Thomas (or just “Frank Thomas,” because who knew from The Big Hurt before 1990?), it wasn’t usually to pay homage to his 34 home runs. Maybe that was because the pre-Kingman Mets hit so few home runs, there was little reason to spotlight the record as aspirational. Or maybe because Frank Thomas was more than a longball barrage.

Things I learned about Frank Thomas from paying attention:

1) He helped serve the meals on a team flight, taking on the role of “stewardess,” as it was put back then. Frank would explain he was impatient and wanted to help get the food on his teammates’ trays. This was considered hilarious in 1962.

2) He dared Willie Mays to throw a baseball as hard as he could before a game to him, with the caveat being that if Frank Thomas caught it, Mays would owe him a hundred bucks…and Thomas had to catch it with his bare hand. Which he did. Frank claims Willie never paid up, but the story itself was something to be dined out on, especially when the airplane meals were slow arriving from the galley.

3) He was not among a small cadre of Mets who understood ¡Yo la tengo! was Español for “I got it!” The Mets who apparently knew were Spanish-speaking infielder Elio Chacon, helpful translator/outfielder Joe Christopher and future Hall of Famer and Midwestern rascal Richie Ashburn who wanted to be able to call Chacon off balls before the two of them would collide. ¡Yo la tengo! was to be the code that would let Chacon at short know Ashburn was rushing in from center with a bead on the ball. Only problem, per all the tale-telling that outlasted killjoy fact-checking, was that Christopher (nor anybody else) communicated to Thomas the meaning of what Richie was suddenly yelling. In any language, another ball fell in when Frank came rumbling into the multilingual picture.

Frank Thomas would deny this ever actually happened. A band out of New Jersey a generation later chose to believe the legend, and thus was born Yo La Tengo, whose members not only revered the Mets but perpetuated the legend. It represented an appropriate coda to Thomas’s Mets career, which lasted until he was traded the pennant-contending Phillies in August of 1964. His numbers could be gaudy. His legend is what created an Original.

The man himself would play through 1966. It got messy between the imported veteran Thomas and rising star Dick Allen in Philadelphia, leading to a hasty release in ’65 and a stop in Houston before second acts in Milwaukee and Chicago. His suitcase was covered with stickers from nearly every National League town, though the two places whose fans continued to take the most pride in him were Pittsburgh, where he went about his life after baseball, and New York, where he established a legend. Here, long after Casey Stengel urged him to maybe not pull the ball so much in yet another dialect (“if you wanna be a sailor, go join the Navy,” which was perfectly understandable if you spoke fluent Stengelese), Thomas remained appreciated by fans who never stopped being grateful to have National League baseball back after the Giants and Dodgers vamoosed. Even those of us who never knew a pre-Mets world could process between the lines when Thomas declared when the return of Old Timers Day was announced in 2022, “To be honest with you, New York is strictly a National League town.”

Thomas was good about sharing his experiences with anybody who’d ask, right up to this past August when he graced Old Timers Day festivities at Citi Field. For further enrichment, go listen to his interview with Jay Horwitz from 2019 or Howie Rose’s YouTube sitdown that same season. Order my friend Dave Bagdade’s recently revised edition of A Year in Mudville: The Full Story of Casey Stengel and the Original Mets to which Thomas contributed his recollections. If you can find it, grab a copy of Kiss It Goodbye: The Frank Thomas Story, which the player produced with co-authors Ronnie Joyner and Bill Bozman in 2005. It’s a 507-page memoir detailing practically every twist and turn of a legendary baseball life. You wish every player would write one. You’re thrilled Frank Thomas did.

If you’re at all interested in Mets history beyond a surface level, you’re eventually going to find yourself reading about or writing about Frank Thomas. Alonso’s pursuit of the home run record; Mets who played both third base and the outfield; Mets who endured to serve as longest-running Mets on their particular rosters. It felt like every time I wanted to blog about anything that stretched back a ways these past few years, I’d run into the name Frank Thomas and run into it with open arms.

You don’t build a franchise like this without a legend like him.

My boys and I had the pleasure of meeting Frank in Cooperstown (at the 2016 Piazza induction). He took the time to talk to us about his tenure with the Mets, including his vehement denial of the “Yo La Tengo” incident! We got a signed autograph of him, Hank Aaron, Eddie Mathews and Joe Adcock pictured together after they hit back-to-back-to-back-to-back HRs for the Braves in 1961. He was very proud of that moment. A true gentleman.

And she’ll like it too

It took me a couple of hours to realize this wasn’t a misplaced Choo Choo Colemanism.

What an excellent tribute to a departed Met hero. Thanks for this.

I was at the August 2, 1962 game at the Polo Grounds. In addition to Thomas’ 2 homers, Marvelous Marv also hit 2 homers, accounting for the 4 runs the Mets scored that day. Unfortunately, Phillies pitcher Art Mahaffey hit a grand slam, and the Phillies won the game 9-4.

All these years later, I still remember this game that I attended as a 14 year old like it was yesterday.

Thank you, Frank Thomas, for the memory and thank you, Greg, for keeping him alive.

RIP. Frank was my coach at Mets fantasy camp in 2000. We had fun with him. He was playing first when I hit a single to right…but the damn shift turned it into an out. The ball, my foot and Frank’s glove all arrived at the same time. Hojo was coaching and said “stay on the bag-that’s a hit!” We all laughed.

This is always the first page I go to whenever a Met passes away. Thanks for the eloquent sum-up of THE Frank Thomas.

And thanks for the links. I knew about the book, but I couldn’t remember the name of it, and for some reason searching “Book by Frank Thomas” only led me to The Other, and some 3rd Frank Thomas, not THE Frank Thomas. That one copy that was available on Amazon? It’s on it’s way to NJ.

And the link to the Howie interview, which I also knew of, but you know, never sat thru. It was the least I could in memory my earliest Met Hero. Inagine talking hitting with Rogers Hornsby, Frank Thomas actually did that, and was still alive to talk about it 3 years ago. (Even if Mr. Hornsby may or may not have said he’d only hit about .280 if he was playing in 1962..because was 62 years old).

Thanks again.

Greg, Thank you for a wonderful blog on Frank Thomas and his legacy with the Mets. It’s a shame we don’t think of the early Mets teams that often as they were part of the magic that has come back and back again and again over the years. Frank Thomas was certainly part of that. Like yourself, he was essentially a name on an old baseball card until Kingman came around and eclipsed his homerun record. I am thankful for those players who gave us a franchise and a memorable inaugural season – even if that meant we lost 102 games. Still magic. We are losing so many people from his age group – my Dad just passed away at 96. This is all part of that greatest generation that we can never forget. Thank you for the tribute. It was fun to read and remember at time that I actually don’t remember but only know from the telling and re-telling of Mets lore. We have to keep this era alive. RIP Frank Thomas and thank you.

What is the truth Greg about the nickname ” Donkey” being applied to Mr. Thomas? I’ve also heard a story that he

caught a baseball that was thrown down from the great Empire State Building or was it from a helicopter. Any truth to that one. Just one inquiring mind to another. He was my favorite Met until Mr. Hunt beat out Mr. Rose for Topps Rookie of the Year.

Bob

The best I can come up with (without a deep redive into Frank’s book) is a big man not necessarily light on his feet invited barnyard comparisons way back when.