It’s mid-March. Spring Training is entrenched until it’s not. Games that don’t matter are the norm until they’re not. If a game is accessible on TV, great. If it’s not, well, it’d be cooler if it was, but, really, no biggie. Players of whom you’d barely heard a month ago are your constants until they fall off your radar for a while or perhaps for good. Something called the World Baseball Classic temporarily enchants or irritates you until it disappears from your consciousness for at least a quadrennium. Back in the Grapefruit League, if a game is tied after nine innings, there won’t be a runner automatically placed on second. Everybody will simply go home or go to dinner. It’s enough to make you shrug.

Spring Training hums along, give or take a finger or forearm or something else that suddenly feels off. If nobody gets hurt, nobody will complain too volubly. During the six months that commence in a couple of weeks, baseball is everything. During the month that follows, postseason baseball, if we’re lucky, is everything and more. Then come the months of preparatory activity for the next six-, ideally seven-month period of everythingness, even if those months when we’re waiting for that — November, December and January — we define mostly by baseball’s void. Those are the months when we shuffle through departures and arrivals and hang our tongues out in anticipation of mid-February, which we convince ourselves will certify baseball’s return. Baseball indeed comes back then, but more as a hint than a fact. It’s just more preparatory activity, except sporadically televised and with uniforms. By the time we get to mid-March, where we are currently, it’s been a month of that and the low hum has set in as if it’s here to stay. The low hum is not enough if you want more, and of course you want more. You start to think about such-and-such date in a couple of weeks and realize there’ll be a game that day that matters without qualification, and it better be on TV. Of course you want that.

But the low hum is enough for now, if not much longer. We have hit the spot when we can sense the actual return materializing beyond the horizon. The WBC will be over and forgotten. The transitory figures will resume their journeys peripheral to our view. A few innings for the starters will become most of the innings. The pitchers’ pitch counts will rise, as will the stakes for those still trying to impress. The injuries will be healed or, like Jose Quintana’s, registered on the injured list, a chronicling we’ll have to take seriously because Opening Day and its Opening Day roster will cease to be theoretical. Then again, the Opening Day roster is the roster for just one day.

In 1975, the Mets conducted an entire Spring Training and exhibition schedule in service to carefully inking rather than penciling in every player who would fill every conceivable role in advance of their Opener, at home, on April 8. Yet the club flew from Florida to New York and discovered that one of the injuries they hoped would heal, that pertaining to Cleon Jones’s right knee and affecting his calf, wasn’t all the way recovered. Cleon, a Met since 1963, would be retroactively placed on what was then known as the DL, meaning the Mets would start the season one brick shy of a full 25-player load. They’d thus need an extra Met ASAP, ideally an outfielder who could swing from the right side. It shouldn’t have taken a nationwide talent search to fill the role. They just conducted that entire Spring Training and exhibition schedule. What’s the point of the Grapefruit League if you can’t pluck one of those players who was about to plummet from your radar and place him on your roster?

As if everything is always that simple. After a month of diligent Florida maneuvering, the Mets considered what they’d seen at or proximate to Al Lang Field and turned their attention west to what had recently occurred in the foreign land known the Cactus League, hiring a player who excelled in Arizona; a player who had been playing against them as long as Cleon Jones had been playing for them; a player who just the other year was part of a successful effort to prevent a world championship from becoming theirs.

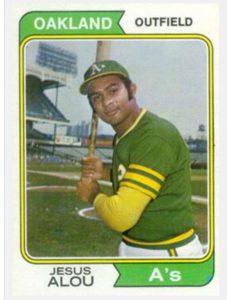

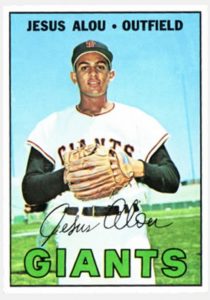

Before the 1975 baseball season was one week old, the Mets welcomed onto their roster Jesus Alou, most recently of the Oakland A’s. We saw him as an A in 1973, during the World Series we almost won, Alou having delivered a couple of key hits in the ALCS to help vault the Kelly Green, Wedding Gown White and Fort Knox Gold (Charlie Finley’s phrasing) into that Fall Classic. We’d seen Alou throughout his career in the National League, dating back to his debut on September 10, 1963, at the Polo Grounds, four days before Cleon himself broke in. Alous were not uncommon sights in the NL, as the Giants had corned the market on all three of them. Felipe had been up with San Francisco since 1958, Matty since 1960. If you became a baseball fan in the seasons that followed Jesus joining his brothers, you were acutely aware that in the sport you chose, there were inevitably three strikes, three outs and three Alous.

Once they were all ensconced within his realm, manager Alvin Dark couldn’t resist introducing them as a trio, pinch-hitting Jesus and Matty directly ahead of Felipe’s spot in the batting order in the eighth inning of their loss to the Mets — “it was like an old vaudeville telephone gag,” observed Harry Jupiter in the San Francisco Examiner — and later inserting each of them as one-third of his outfield for spells in three September blowout wins. This meant sitting Willie Mays, an act Giant skippers habitually resisted if a game’s outcome was in doubt. The last time Alou-Alou-Alou constituted the SF outfield was September 22, with the Mets visiting Candlestick and losing by eleven. Alou ended the game by catching Chico Fernandez’s fly to right.

To be specific, that was Jesus Alou, playing right, while Matty manned left and Felipe patrolled center. For a few weeks, you had to specify your Alous and their positions. In the ensuing offseason, Felipe would be traded to Milwaukee, and two winters later, Matty would be sent to Pittsburgh. Jesus, however, established himself as the Giants’ right fielder in 1964. According to the back of the 1967 Topps card where I made his acquaintance, “the San Francisco brass feels that Jesus has even more potential than his two brothers now in the majors,” though unlike Felipe (three times) and Matty (twice), Jesus never made an All-Star team. He did hit as high as .298 over a full season for the Giants, not bad for a) a converted pitcher and b) “the baby” of the family, which is how I saw him identified in an article when I was a kid and found it kind of curious that a grown man was referred to as a baby. I was also pretty taken by the youngest Alou’s first name. The first Jesus, any pronunciation, I ever knew of was Alou.

The Giants may have harbored all three Alous, but they also eventually let go of all three Alous. Jesus was exposed in the 1968 expansion draft and selected by Montreal. Montreal opted to include Jesus in a trade they had no idea would be the most consequential of 1969, the one that shipped Donn Clendenon to Houston for Rusty Staub. The consequence rippled from Clendenon’s refusal to go to Texas, which meant Donn was still hanging around in Quebec in June, perfect timing for the Mets to take off the Expos’ hands the veteran slugger who’d become their World Series MVP four months thereafter — and let us not overlook the foreshadowing inherent in mentioning Rusty Staub. None of that was of consequence to the youngest Alou, who would top .300 twice as an Astro and appeal to Oakland as a veteran pickup in 1973. Those A’s were always adding experience on the fly en route to crafting their surprisingly sturdy dynasty, chronically antsy owner Charlie Finley happy to make short-term deals and not have to pay anybody too much for too long. (Ex-Met Art Shamsky was a briefly a cog on the World Series-bound A’s of 1972.) Alou would play a pivotal role in ’73, stepping in to take over right field late in the season when Reggie Jackson encountered a hamstring injury and allowing Jackson to shift to center when Bill North got hurt shortly before the postseason. His contribution kept him with the A’s as they achieved their threepeat in 1974.

Come the spring of ’75, Jesus possessed two World Series rings but no guarantee he’d continue with the defending world champions despite hitting .586 against Cactus League pitching. Finley’s A’s relished speed in the form of pinch-running specialists. They already famously retained the services of Herb Washington, who literally did nothing but run for Oakland. They were now intent on adding the ultimately less-celebrated Don Hopkins to replicate Washington’s core competency. More speed off the bench meant less space for existing lumber. In other words, goodbye Jesus.

That amounted to a welcome development on the other side of the country, because the Mets had been keeping an eye on Alou. Bob Scheffing, who had been replaced as GM in the offseason, was scouting Arizona and believed in Jesus. Scheffing had a disciple in his successor as general manager, Joe McDonald, and Joe made Jesus an offer. Alou had thought about playing in Japan, where middle brother Matty had alighted with the intent of hitting for average and being compensated well for it, but this Dominican native decided he preferred playing ball in North America.

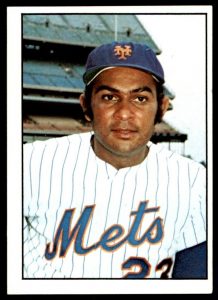

“We’ve made no promises,” McDonald said upon announcing the acquisition of Alou. “He knows he can be released again. We want him to pinch-hit.” Alou, in turn, was motivated: “I do not want to lose two jobs in a month-and-a-half. All I need is a batting practice or two, and I’m ready.” Jesus, the 32-year-old baby brother in baseball’s most famous troika of siblings since the DiMaggios, had been around, and didn’t require extensive preparation beyond knowing when the bus left for the ballpark. The veteran noted with pride to Daily News reporter Augie Borgi, “I have not missed a bus in seventeen years.”

Despite no Mets fan who diligently tracked Spring Training 1975 making out prospective rosters with the name “Alou” included, the career .279 hitter was suddenly one of ours as of the new season’s second series, in Pittsburgh, and he made his Met debut in the club’s seventh game, at St. Louis. He was a known quantity from a distance, if no more than a contingency ‘x’ factor plopped atop our meticulously considered personnel scheming and dreaming. Maybe we’d get a kick out of finally having an Alou on our side after taking on one or the other let alone all three at once for so long. As fans, we could make no promises, either.

At some point, whatever thoughts McDonald might have maintained about Jesus’s tenuous grip on permanence dissolved. Ours, too. Alou, the first Met World Series opponent determined to make it up to us by joining our side, lasted the entire year and did exactly what the Mets signed him to do. They needed a pinch-hitter? They got someone who established himself as a true specialist. The righty came through time and again, going 14-for-40 for a .350 average as a pinch-hitter. With Ed Kranepool starting more than anticipated, Alou emerged as manager Yogi Berra’s primary pinch-hitter — Roy McMillan’s, too, once the first base coach replaced Berra. Not only did Alou outlast his first Met manager, he endured longer that season than Cleon Jones, who didn’t return from his springtime injury until late May, only to be released ignominiously in July. Alou’s solid ’75 in a niche capacity, not to mention amid a whirlwind of organizational turmoil, earned Jesus a Spring Training spot in 1976. Alas, a visa problem delayed his reporting to St. Petersburg (if only he could have hopped a bus from the DR) and the Grapefruit League success of another, younger pinch-hitting candidate — lefty Bruce Boisclair — resulted in the veteran’s release.

“Jesus is a nice fellow,” said new manager Joe Frazier, echoing what people throughout baseball thought of Alou, “But when [injured] Mike Vail comes back, we need the spot. We have kids with options. You can understand our position.” Alou had been around and got it. He pulled back from playing for a couple of years, but wasn’t done. Jesus returned to action with the Astros in 1978 and 1979. Baseball’s quintessential kid brother played until he was 37 and stayed in the game long after, most notably as Dominican Republic scouting director in this century for the Red Sox, to say nothing of his uncle-ing Mets reliever Mel Rojas (1997-1998), Mets outfielder Moises Alou (2007-2008) and Mets manager Luis Rojas (2020-2021). Jesus Alou, who died last week a little shy of his 81st birthday, lived a long and distinguished baseball life, a year of it as a Met, the entirety of it as one-third of an even more exclusive club.

Unless you were in the outfield for San Francisco on September 15, 17 or 22 of 1963. In that case, everybody you saw was just another Alou.

A lovely and fitting tribute.

Greg-

Great memories–I do not recall Jseus in the 73 WS-but prior to that, I do recall the outfield full of Alous a few times.

RIP in Baseball Heaven and get that twitchy neck tended to!

Greg, what an Amazin’ tribute. I too first heard of a Jesus as a person, in the person of Jesus Alou.

And he had that big leg-kick before he swung the bat.

Another fella passed this month, closely associated with the Mets, though as an opponent. Dan McGinn famously pitched against the Mets for Montreal in their first game ever, in 1969. He hit a home run off Seaver in an 11-10 victory, the first home run in Montreal history. You can actually see it on YouTube and Twitter, from the Canadian Broadcast. I had never seen that play before.

The only home run of his career.

No Tommy Hutton, but quite an achievement nonetheless.

Well, Diaz may have broken his leg during the WBC celebration after getting a save….

I kid you not.

Guess Robertson is our closer now…

Sheesh.

As long as the “WBC” keeps getting shoved down our throats with no regard for the hundreds of millions being paid to professional MLB players or the millions of fans paying to see MLB baseball once the season begins, this will continue to happen. Perhaps when a position player suffers a career-ending injury, they’ll put a stop to this risky and ridiculous waste of time.

Testify.

RIP. Jesus Alou is a little before my time, but I remember reading that NY sportswriters renamed him “Jay Alou” because they didn’t want to write a headline like “Jesus Strikes Out”. My thought is, the Alou side of the family is always welcome in the Mets universe. The Rojases, not so much.

I will withhold my comments on the Diaz debacle until our gracious hosts have weighed in. Other than to say, here we go again… (sigh)…