When your opponent puts double digits in the run column and you win, anyway…

When you record a final score in your favor that you haven’t posted since the final months of the previous century…

When the prohibitive favorite to lead your team in his signature category for a record-tying fifth consecutive season might be compelled to glance over his slumping shoulder…

And when your kooky line score hardly looks lonely when inserted onto an out-of-town scoreboard…

Then you turn to ABBA’s conversation with that Fernando fella for inspiration, for there was something in the air Tuesday night, and we’re not talking smoke from a distant Canadian fire.

The Mets won an 11-10 game, which is something they hadn’t done in 24 years, and when they did it on May 20, 1999 — propelled by a Robin Ventura grand slam home run (a feat he’d duplicate in the second half of that evening’s doubleheader) — it was a first. Those Mets birthed a Unicorn Score, which means that on Tuesday these Mets gave us a Uniclone Score at which to marvel. Any time you get a score the franchise has won with only twice, you simply have to pause and marvel, though it hardly felt like the only marvelous takeaway from the Mets edging the visiting White Sox, 11-10.

While New York (NL) was Eleven-Tenning Chicago (AL), the same act was being carried out in Cincinnati by the Giants over the Reds, and in Kansas City, where the Tigers were the high-rolling losers. What could be more breathtaking than processing THREE 11-10 ballgames on the same night? How about a game in which the winner and loser each scored more? That was the tale told in Atlanta via Diamondbacks 16 Braves 13 — and Arizona didn’t even top the run pool Tuesday night. The Cubs scored 17 in blowing out the Nationals by 14.

The Dodgers scored 10 in bopping Baltimore. The Guardians scored 10 in pasting Pittsburgh. The Twins scored 10 in smashing Seattle. The Padres were pikers, plating only 9 in torching Toronto.

Mamma Mia, that’s a lot of runs! My, my, how do you explain it? My pet theory is the fifth day after the All-Star break brought out a surfeit of back-end starters who hadn’t pitched in well over a week, and their rust showed. At Citi Field, the White Sox threw Lucas Giolito, who hadn’t gone in nine days. He was opposed by Carlos Carrasco, toeing the rubber for the first time in twelve days. Counterintuitive to the sense that a well-rested pitcher should be able to stay on the mound longer than usual, neither lasted long enough to qualify for a win.

Not that that was going to be a concern for Giolito, the rare opposing pitcher to fully enable the Mets in a first inning. The Mets scored five times out of the gate. Giolito lasted into the fourth, but whatever length he was providing the Sox wasn’t worth the bullpen preservation. The Mets were up, 7-2, when he departed, and then added another run charged to Lucas’s ledger.

Up 8-2 in the fourth! The Mets ahead from the start and never to trail! A laugher!

Funny thing is, no. Maybe not so funny a thing. True enough that the Mets led the game and were neither headed nor tied, but on a night like July 18, 2023, as evidenced by the plethora of runs from coast to coast, no lead that wasn’t gargantuan was quite safe. Carrasco waded into too much troubled water and the Mets needed Grant Hartwig to bridge the conclusion of the fifth inning. No win for Carlos, which only matters when you develop the sneaking suspicion that the laugher already in progress is about to be pre-empted so we can show you a nailbiter.

Oh, but let’s remember the good times. Tommy Pham hitting hard and running free of groin encumbrance. Jeff McNeil returning to something resembling offensive life. DJ Stewart becoming the 87th Met to hit exactly 1 home run as a Met (and making a case for more playing time so he can attempt to extract himself from the 1 Home Run as a Met list by belting another). Brett Baty going very deep to remind us he’s more than the guy who unsuccessfully circled under a popup on Saturday. And, most marvelous of all, Francisco Alvarez and his two home runs, giving the rookie 19 on the year, which is astounding for all sorts of reasons, none less so than Alvarez has pulled to within seven homers of Pete Alonso for the team lead.

Since Pete Alonso came up in 2019, no Met has finished a full season remotely near the Polar Bear in the home run category. Michael Conforto finished second to Pete by 20 four years ago. In 2021, Francisco Lindor was the runnerup by 17. Last year, Lindor took the silver medal again, finishing 14 behind Alonso. Even within the limited parameters of 60-game 2020, the race wasn’t particularly close: Alonso 16, Dom Smith 10, Robinson Cano 10. When Pete stormed forward this season, one could begin to pencil in a fifth consecutive team home run crown for our slugger-in-residence, which would tie him with Mike Piazza in Metropolitan slugging streak supremacy (Mike led the Mets in homers every year from 1998 through 2002; no other Met has outhomered each of his teammates more than three years in a row). Alonso blasted his 10th home run of 2023 on April 21. Hitting more home runs than all of the 1980 Mets loomed as a more likely challenge for Pete than fending off any 2023 Met.

Yet on April 23, Francisco Alvarez hit his first home run of the season, and from that moment forward, Francisco has outslugged Pete, 19 to 16 (he’s also pulled aside Lindor in the all-Francisco lane for the entire year). Alvy’s momentum has been a sight and sensation to behold. We’d be best off with each of the A&A Amigos cranking balls out of yards — or, in Pete’s case, maybe recording a few singles and getting untracked — but Francisco sneaking up on the dinger king of Flushing has been an unexpected surprise and, frankly, kind of delightful.

The White Sox sneaking up on the Mets as Tuesday night went along was less so, yet there were the Pale Hose, weaving serious business from a prospective laugher, closing gaps of 8-2 and 11-4 until the Mets found themselves clinging to a one-run lead in the ninth. The potential tying and go-ahead runs had reached third and second, with Tim Anderson, undergoing his own Squirrelish renaissance, at the plate, and David Robertson barely hanging on. Yet Robbie induced a fly ball to center that flew no farther than Brandon Nimmo’s glove, and there we had it: the 15th victory in Mets history that encompassed at least 10 runs for the losing side. That sort of thing last happened two years ago today, in Cincinnati (Mets 15 Reds 11); had never happened previously at Citi Field; and happened most famously on July 4 and 5, 1985 (Mets over the Braves, 16-13, the same score by which Atlanta lost Tuesday night, which is fun to mention again). In a better year, the ability to follow up a 2-1 win with an 11-10 win could be taken as some sort of sign. Taking them together as a pleasant pause from the otherwise desultory norm will do fine for now.

That’s not just power. That’s staying power.

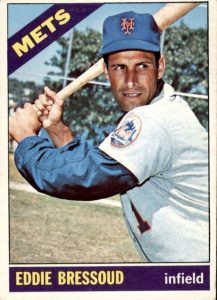

When Bressoud — rhymes with ensue — arrived in New York, the most home runs any Met shortstop had hit in a season was two. Eddie shattered that mark and then some, knocking 10 homers over fences in ’66. It was a good year for a veteran player to set a standard as a Met, as the Mets, reinforced by the presence of several veterans, set their own standard. They were the first Mets team to finish above last place and with fewer than a hundred losses. Like 10 homers by one player in one year (remember, Alonso had 10 this year by April 21), winding up in ninth place by going 66-95 may not strike the uninitiated as an accomplishment, but progress was progress. In 1966, the Mets of Eddie Bressoud were progressing from the dregs of the National League to something somewhat less dreggy.

Eddie wasn’t a building block in Flushing. He was filling a need for an established shortstop with a little pop while the good-glove youngster on whom the Mets had their eye for the position longer-term, 21-year-old Bud Harrelson, worked on his hitting in the minors. Bressoud thus succeeded slick fielding elder statesman Roy McMillan and kept the middle of the infield professional while Buddy summered at Triple-A Jacksonville, learning to swing from both sides of the plate (a career-altering course inspired by an incidental Spring Training encounter Harrelson had with a club executive by the name of Charles Dillon Stengel). Shortstops in those days for the most part were asked to field first and hit later, if at all. On the Mets, from Elio Chacon through Al Moran and McMillan, power was not part of the shortstop job description.

Bressoud reset that expectation during his one year as a Met. That record he set he took with him when he was traded to St. Louis before the start of the 1967 season. By then, Harrelson was ready to play short, which he did to great defensive effect for the next ten years, yet for all Buddy derived from his ability to switch-hit, he was never gonna be a home run guy. Nor were his part- or full-time successors Mike Phillips, Tim Foli, Frank Taveras, Ron Gardenhire, Jose Oquendo or Rafael Santana. It wasn’t until Kevin Elster, a Harrelson protégé, settled in as the regular shortstop that a Met who manned that position regularly matched Eddie Bressoud’s home run output. Kevin socked 10 homers in 1989, tying Ed. That remained the shared record until 2006, when Jose Reyes forever redefined the notion of production by a Met shortstop, hitting 19 homers.

Mets fans of a historical bent recognize Bressoud’s name for another reason Eddie came up to the majors with the New York Giants in 1956. By joining the Mets a decade later, he became the first alumnus of the departed New York National League ballclub to play for their successors. One of the enduring myths of Metsology is the Original Mets were stocked with old Dodgers and Giants to draw in the fans left abandoned by the teams that occupied Ebbets Field and the Polo Grounds. That’s half-true. Lots of Dodgers: Hodges, Zimmer, Neal, Craig, Labine briefly, Snider in the second year. No Giants, though, at least not in the players sense.

You certainly had Giant DNA on the premises. You had Mrs. Payson, who owned a sliver of the Giants in New York and couldn’t just let her fortune sit in a vault when there was a chance to replace them once they bolted. You had Ol’ Case, who starred in World Series play for the Jints in the 1920s but whose scampering around the bases days were through by 1962. You’d have old catcher Wes Westrum serving as Casey’s coach starting in 1963 and, eventually, the team’s manager when it leapt from tenth place to ninth. You had 1954 World Champion Giants ace Johnny Antonelli demurring when the Mets purchased his contract in 1961, choosing to retire instead. And, shoot, you had the Polo Grounds welcoming the Mets to Upper Manhattan as the neighborhood’s new home team. But it took until 1966 for an actual former NYG to take on the identity of NYM. That was Bressoud.

The second and last former New York Giants to play for the New York Mets wouldn’t show up for another six years. His name was Willie Mays. If it were up to Mrs. Payson, Willie would have been a Met from the beginning. If it were up to Mrs. Payson, Willie and the Giants would have never left.

In the ’61 expansion draft that stocked the Mets so (ahem) abundantly, it’s pretty well known that the Mets did pick a San Francisco Giant with their first pick, catcher Hobie Landrith. Hobie had his own mythology. Less known, outside of Houston maybe, is that the first pick overall, once the Colt .45s won the coin flip, was Eddie Bressoud. By then, Bressoud was, like Landrith, a Giant of the SF variety. The future Astros grabbed him, but then traded him to Boston for Don Buddin. Boston got the better of the deal, as Eddie would go on to reach the All-Star Game for the Red Sox in 1964. The site of that Midsummer Classic was Shea Stadium. From the American League bench, Eddie perhaps made a mental note that he liked the joint and wouldn’t mind getting to know it better. That opportunity arose prior to 1966, when the Mets traded their erstwhile .300 hitter Joe Christopher to Boston to get Bressoud.

“My wife always said that was the most fun place we ever played,” Eddie told author Bill Ryczek for his 2008 book about the Mets of the 1960s. “She described herself as a participant rather than a spectator. There was an awful lot of excitement in the ballpark all the time. We were being beaten by eight or nine runs in the seventh, eighth or ninth inning, and the ‘Let’s Go Mets’ chant would start up. You’d feel, ‘Golly sakes, they’re really with us’ and you’d try a little harder.”

The Mets weren’t hopelessly out of games as often as they had been previously during Bressoud’s lone year in orange and blue. If he remembered it fondly, he deserved to be remembered just as fondly. On his Ultimate Mets Database fan memories page, it appears his relatively brief detour through Shea Stadium left an impression beyond his longstanding shortstop home run record. The best comment attesting to his legacy:

Eddie drives up to the players lot behind the Met bullpen. Kids would hang there early and scream for tickets as the players pulled up. Eddie reaches out with 2 tix and says, “Don’t sell these. I’ll be watching for you.” My friend and I go inside and we are right behind the Met dugout 3 rows back. Eddie starts that day and first time up he looks back to see if we’re there. We wave and yell “hit a homer, Eddie!” Of course he does and we go nuts. He comes back to the dugout, looks at us and smiles. For two 15-year-old kids, it made our decade.

Eddie spent more than a decade in the big leagues, winding up with the Cardinals in a supporting role as they won the 1967 World Series. The Mets had sent him to the Redbirds in exchange for second baseman Jerry Buchek. Harrelson was going to get his shot at short, and that would work out pretty well. Meanwhile, the rest of Bressoud’s life, in and out of the ranks of pro ball, worked out more than splendidly. “He was a true family man,” Ed’s son Steve told the Vallejo Times-Herald, and noted his dad took it upon himself to be “an ambassador for the Giants, no matter where he went. He would see someone wearing a Giants hat and instantly strike up a conversation with him.”

Bressoud may have been a lifelong Californian, but he carried a certain New York distinction beyond the Mets-Giants connection. Few are the people who can any longer say they registered at least one regular-season base hit at the four primary 20th century ballparks of New York City. Eddie was one of them. He started out at the Polo Grounds and got a hit; he showed up in time to play a little at Ebbets Field and got a hit; his trade to Boston positioned him to visit Yankee Stadium, where he got a hit; and then came to the trade back to the National League and his introduction to Shea Stadium, where he not only got hits, but made a couple of kids’ decades. Well before Interleague play, when even trades between the NL and AL were infrequent and free agency was nonexistent, players didn’t really move much between leagues, so the chance to collect a hit in each of those four stadia was fairly uncommon. That Bressoud pulled it off by a) playing home games at the Polo Grounds and b) playing home games at Shea Stadium without c) having played home games at the Polo Grounds as a Met makes it all the more noteworthy.

To the best of my calculating, the 4 Borough Hit Club went out of business once Hank Aaron and Frank Robinson retired in 1976. It was already pretty sparsely staffed by the time Bressoud finished playing in 1967. Its survivors today include Ozzie Virgil, Sr. (one of the nine remaining living New York Giants) and Original Met Felix Mantilla, a teammate of Bressoud’s in Boston. There may be a few others I didn’t detect when researching the matter, but there can’t be many still around. You had to play well enough long enough to span multiple eras and be wanted on multiple teams, and to be able to claim the distinction more than a half-century later, you had to have lived quite a life after baseball.

Eddie Bressoud did all that.

Of course Francisco Alvy *shouldn’t* be catching up to Pete, if it wasn’t for Pete falling off a cliff lately.

Even the wins feel like losses these days…

Always a pleasure, Greg. Let the Chatbot top THAT!

Appreciate it, Eric.

I was at the game in 1966 when Bressoud hit 2 homers and Dick Rusteck pitched a shutout for his only major league win, beating the Reds 5-0.

Rest in peace, Eddie.

[…] That’s Powerful Stuff » […]

Beautiful tribute.

Thank you, Rumble.