In one of those Faith and Fear traditions known only to me, I like to present a list as long as Eric Hillman’s left arm when my birthday falls on a Sunday. Since we’ve been doing FAFIF, my birthday has fallen on a Sunday twice, in 2006 and 2017. Today is the third time. I’m keeping my obscure tradition alive by presenting the first portion of a list I’ve been nurturing for several years.

These are MY FAVORITE MET SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT. Such a list itself wouldn’t be too long if it was just the list: 55 seasons that I’ve been watching the Mets, 55 lines on the list, done and dusted, go watch the ball drop. Of course a simple list with no expanding on the subject matter wouldn’t be any Sunday birthday fun for me. Being expansive about the Mets is what’s gotten me to 61 in as good a mood as I can be.

Creating a commentary-laden list that goes from least favorite to most favorite rides a somewhat predictable arc in my thinking. If I were to start with No. 55, the Met season I liked least from a personal perspective, I’d be very down on No. 55, and stay down for the first wave of the countdown because, you know, they’re my least favorites. “This went wrong, that went wrong, what a year, yeech.” It’s understandable. When you love a team the way we do, you really hate when things go badly for them and that’s gonna come through in any retelling.

I want to be in a good mood at the outset of 61. So here’s how I’ve decided to proceed. For the first dozen entries on the list of MY FAVORITE MET SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT, I’m devoting myself to Something I Liked In Seasons I Didn’t. One distinct memory apiece from those dismal dozen when I can remember feeling pretty good in some way about and during a lousy Mets year. It was a bit of a challenge finding something nice to say about those Met circumstances that had little to recommend them when they were being lived, but that made taking it on more fun for me to put together. (This, you’ll note, is how I have fun.) I also tried my best to come up with material I haven’t used here before or at least haven’t delved into in quite the same manner. Apologies for any long lost redundancies. Apologies, too, for briefly transporting you to seasons you might wish remain lost. For me, “least favorite” implies some strain of favoring, however slight it might be.

Bob Murphy continually reminded us baseball is a game of redeeming features. Every season has those. That’s what this segment of this countdown is all about.

I’m limiting myself today to one glass-half-full anecdote for twelve mostly empty seasons. The seasons that are more favored will be counted down in a different style in upcoming posts. That’s the plan, anyway. I’m a tad pokey about following through on these multipart series ideas of mine, but we’re getting the least-favorite seasons out of the way right here, right now. It can’t help but get sunnier in the new year.

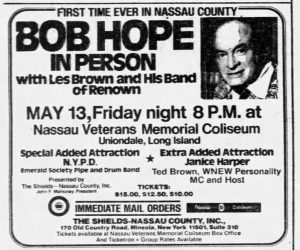

Bolstered by the magic of twi-night doubleheaders, the Mets played 29 games on Fridays in the year they a) traded Tom Seaver on June 15; b) determined the National League East cellar would make a nice long-term rental; and c) left few positive impressions in their wake. They lost 21 of those particular dates, including nine in a row spanning May 20 to July 1, indicating maybe Friday wasn’t destined to be their lucky day of the week whether they held onto The Franchise or not. Yet my clearest memory of any Friday game from 1977 comes from a win: Friday the 13th of May. My friend’s father had come into a boatload of tickets for a Bob Hope show at the Nassau Coliseum that night and was quite generous with his windfall, inviting my parents and me to join a rather large party to watch the ageless comedian ply his craft. I remember one Hope joke: President Carter has reached out to fill the White House with advisers from the north, south, east and west…of Georgia. I also remember the lot of us going out for ice cream at the Apollo Diner in East Meadow afterwards. So I didn’t see the game, but I recall getting home in time for Kiner’s Korner, from which I learned Dave Kingman had homered and the Mets had topped the Dodgers at Shea, 3-0. Sky King had been in a mood all season — he’d be traded the same night as Seaver — but here he was, performing his Dave Kingman core competency, hitting a “long, towering two-run homer,” per Steve Jacobson’s description in Newsday, two batters after Lenny Randle sent his first Met dinger over the 396 mark in left-center. “An accident,” the good-natured newly acquired infielder called his shot. “My quota is about one a year.” Randle made some nice plays at second, as did contingency third baseman Jerry Grote at his temporary position. Jon Matlack threw a seven-hit shutout to quell the Dodgers, who entered the evening at 24-6. Conversely, the Mets had won once in the past dozen days; they hadn’t even led in a game since the previous Sunday. Before Jon beat L.A., the Mets were 10-19. A few days earlier, the lefty revealed to Joe Durso of the Times that he was “fed up” with how the Mets were going about their business on and off the field. Kingman’s reaction to his eighth homer of the year (and second-to-last before he became a San Diego Padre)? “I don’t care anymore. I just play my game.” The Mets hadn’t exactly turned their frown upside down, yet this game got played to a pleasing decision for a change. Ralph had bona fide home team highlights to share and the 1977 Mets provided me with a wisp of optimism that these guys might pull themselves together rather than continue to completely fall apart. They didn’t, but for a minute I could be convinced otherwise. Thanks for the memory?

54. 2003

“I hated the Dodgers with that love that only hatred can understand,” is how Stephen Jay Gould summarized being a Giants fan in 1951 on Ken Burns’s Baseball in 1994. I’ve mulled that sentence over for nearly thirty years, and I still don’t know what it means, but I’ve always liked the way it sounded. Perhaps that also fits how I viewed the Mets in 2003. They replaced Bobby Valentine with Art Howe. They let my favorite player, Edgardo Alfonzo, walk. They dumped my wife’s favorite player, Rey Ordoñez. They imported T#m Gl@v!ne from the Braves and Mike Stanton from the Yankees. They created the first Mets team that I pretty much hated in advance, albeit with a hatred informed by love. Or something like that. It was as unlovable an edition as I had encountered in all my years of being a Mets fan, but I was still a Mets fan, regardless that I couldn’t stand these Mets. I still cheered for various Mets. Sometimes they were wearing other uniforms. On June 6, the Seattle Mariners came to town, which meant John Olerud was coming to town, which meant I would be at Shea Stadium to let John Olerud how much I missed him. I was almost as irritated with the Mets letting Oly go in December 1999 as I was with their making the same decision vis-à-vis Fonzie three winters later, but those Mets had too much going for them to seriously test my ardor. In 2003, I’d already rooted for an ex-Met over a current Met once, when Jesse Orosco filled in as closer for the Padres on May 9 and his chance to notch a save at Shea — something he’d done most memorably one October night versus the Red Sox — meant he’d have to retire Roberto Alomar. I already didn’t like Alomar. I was watching from home. It was an easy call. C’mon, Jesse. Orosco struck out Alomar with two on and two out. I clapped for the pitcher. The Mets lost? So what? 1986 took a curtain call, something 2003 would never be asked to do. Four weeks later, though, my fondness for Olerud and all he’d meant from ’97 through ’99, couldn’t quite break through another ninth inning. This time I was at the game. It didn’t matter that I loved Oly and I was past the end of my rope with Armando Benitez. Armando was protecting a one-run lead with two out and a runner on first. He was as capable of blowing it as he was of saving it. A Met win wasn’t going to mean anything in the scheme of 2003. John worked a three-two count. Of course he did. He was beautiful that way. Benitez was agita personified. The Mets deserved to have John Olerud, in his first trip back to Flushing since he advanced unmolested from second to third once the Grand Slam Single departed the park, remind them of who they felt fine about replacing with Todd Zeile. Yet, I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t root for one of my favorite Mets to stick a pin in the world’s largest Armando Benitez voodoo doll, not as long as he was a Seattle Mariner in my midst. Benitez struck out Olerud. I approved. It was the approval only disdain can understand. Or something like that.

53. 2002

My dismay for the 2002 Mets wasn’t set in stone ahead of time as it would be in 2003, but it was inevitable. Bad mix of personalities, bad results the rule by May, a total disaster by September. Still, on September 21, a Saturday night at Shea — and I’m not a huge fan of going to Saturday night games to begin with — I’d forgotten how disgusted I had become with the 2002 Mets over the previous five-and-a-half months once the Mets forced extra innings versus the Expos. Did I say “forced”? More like the Mets walked through the door to the tenth Montreal held open for them in the bottom of the ninth. Sure, the Mets had first and third, but with two out, Brady Clark grounded to two-time Gold Glove winner Andres Galarraga at first. All Galarraga had to do was throw accurately to second to end the game, 3-2, in favor of Les ’Spos, but Andres’s last Gold Glove came in 1990. His errant fling into left field furnished the Mets with the tying run. Come the eleventh (after Armando Benitez held up his end of the bargain with two scoreless frames), Joe McEwing absorbed a hit-by-pitch with one out, Roger Cedeño drew a base-on-balls with two out, and Esix Snead, the kind of player for whom garishly expanded rosters were conceived, belted a three-run homer to win it. Esix had been on the club since September 3, primarily to pinch-run. He entered this game as a pinch-runner in the eighth and was picked off. In the tenth, he delivered a leadoff single for his first hit in the major leagues, but was stranded at second. Snead left no doubt in the eleventh. “It’s pretty exhilarating,” the rookie said, expressing a sentiment nobody around the Mets had any cause to otherwise articulate of late. A week remained in the season. The Mets were going nowhere and they were doing in front of almost nobody. But as soon as Snead went deep to right, those of us who’d stuck around to the non-bitter end had detoured into a September to Remember. I was jumping around like House of Pain was back on the charts, high-fiving my pal Joe over and over and truly believing there was no better place to be on a Saturday night than Shea Stadium at the tail end of a last-place campaign. Hot damn, I was at The Esix Snead Game.

52. 1992

They weren’t yet dubbed The Worst Team Money Could Buy, but had you told the bulk of Mets fans by June 1992 that a book bearing that title would be out the following April and it would be about this team that was repeatedly frustrating us, we wouldn’t have blinked. Ah, but before it was abundantly clear what a debacle we were bearing witness to, there was Daryl Boston’s shirt and the ball that landed inside it. It was the sunny afternoon of April 23, a Thursday matinee at Shea. I wasn’t there, but I was close enough, sitting at my desk in Great Neck with the radio on, enjoying one of those day games that feels as if it’s never gonna end, now and then sharing updates with co-workers who cared and co-workers who didn’t. Bret Saberhagen pitched nine scoreless innings. Alas, so did a combination of two Cardinal pitchers, which meant extras were at hand. The eleventh was to be our downfall, if you assumed two singles and a walk to the opposing lineup with nobody out augured the worst. Assume nothing — Dave Magadan made two swell plays at third base and St. Louis couldn’t score. Still zip-zip, all the way to the bottom of the thirteenth, when the Mets loaded the bases, bringing up Boston. Redbirds reliever Juan Agosto managed to land a one-two pitch inside the loose-fitting jersey of the batter. It went onto your scorecard as HBP and RBI. Daryl plucked the ball out of his clothes and handed it to the umpire. Mets 1 Cardinals 0 in a shade under four workday hours. Some kind of omen for the season ahead, the listener at his desk thought before starting to spread the news throughout the office. It was no kind of omen, actually, but it was April, and the team for which he rooted seemed to be worth whatever they were being paid.

51. 1993

If ever a team inspired a fan to agree with McDonald’s that we deserved a break today, it was the 1993 Mets, whose rousing 12-2 victory over the Reds in Cincinnati on Wednesday August 18 raised their seventh-place record to 42-78, a mere nine games behind sixth-place Florida, a team that hadn’t existed before the current season. The Mets had a travel day Thursday, then a scheduled off day Friday before resuming their schedule in Colorado on Saturday evening with a twi-nighter against the NL’s other expansion team. No baseball planned for Friday was odd but explicable. The Denver Broncos had a preseason game at Mile High Stadium, so the Rockies had to work around the venue’s primary tenant’s priorities while Coors Field was under construction. Being left alone by the 1993 Mets sounded heavenly. I filled my Thursday evening void by tuning into the staticky Phillies’ broadcast on 1210 AM (Lenny Dykstra’s bunch had a certain appeal), and I was musing that if I absolutely had to, I guess I could go on as a baseball fan without the Mets if I had a strong enough antenna. Then Friday came, and the godawful Mets remained in absentia, and so help me, I missed them. Not that team and its toxicity, just the day-to-day Metsiness of what a season is supposed to give us, even in the moldy basement of a season like the one in progress. The 1993 Mets returned to action Saturday and lost twice to this other team that hadn’t existed before the current season. Everything was still lousy. Everything was all right again.

50. 1979

On one hand, there was a final dress rehearsal. The Long Beach High School production of Li’l Abner would have its world premiere on Friday night, April 6, featuring for one scene yours truly in the key (from an expository sense) role of Senator Jack S. Phogbound. But the Thursday afternoon before, directly following eighth and final period, we would run it through one time as if we were going on stage in front of an actual audience…which we were, courtesy of a group of seniors — actuarial rather than high school — bused in from a local nursing home. The show went great, and our cast was brimming with confidence ahead of Opening Night. The only fly in the ointment was the final dress rehearsal conflicted with the curtain rising on the 1979 Mets season in Chicago. Alas, in order to deliver my briefest of solos (of all the very/ordinary/most unloved/unnecessary/places on this earth…), I had to miss the first pitch from Wrigley and the initial innings of the new year as well. Thankfully, I was home in time for the ninth. The Mets had a 10-3 lead, built largely on Richie Hebner’s four-hit, four-RBI debut. They always won on Opening Day, right? The Cubs, however, stirred and made it 10-6 with a runner on when Joe Torre went to his 21-year-old rookie out of the pen, Jesse Orosco, the player to be named later from the Jerry Koosman trade. Our callow southpaw, wearing No. 61 without a name on his back (all his teammates were properly identified), would have to face one of the most dependably dangerous lefty swingers in the league: Bill Buckner, a .323 hitter the year before. This was a game that couldn’t get away, and it didn’t. Orosco induced Buckner to fly to right, and the Mets were perfect in 1979. As, I daresay, was Li’l Abner on Friday night. Saturday night’s show, however, lacked that certain something, but that was OK, I guess, considering it was our Closing Night. Besides, the Mets won Saturday afternoon. We were 2-0. Hebner was batting .556. I never performed in another musical again. The 1979 Mets, about to lose 99 games, might have considered taking a cue from the ol’ Senator here.

49. 1982

I was a car washin’ college man on a Sunday afternoon, making like Judge Reinhold as Brad Hamilton in Fast Times at Ridgemont High in the driveway of our house a couple of weeks before I was due back on campus. Determined to take care of my burnt orange 1981 Corolla (or, more likely, nagged into it by my mother), I had the hose, I had the bucket, I even had a fresh tin of Turtle Wax, a product I thought existed only as a consolation prize on Let’s Make a Deal. Whereas Brad scrubbed his “Cruising Vessel” to the strains of “Raised on the Radio” by a group called Ravyns, I went about cleaning my baby with WMCA on in the background. I was raised on the radio for Mets games if Channel 9 wasn’t televising them. Bob Murphy was exclusive to radio as of 1982, joined by newcomer Steve LaMar. In the first game of the doubleheader of August 15, Murph and his freshman partner kept me effervescent as I rinsed the bubbly water off my “Orange Flame”. The Mets took a lead in the fourth. Ed Lynch pitched serviceably for seven. When Jesse Orosco struggled in the ninth, George Bamberger called on Pat Zachry with the bases loaded. Pat worked out of Jesse’s jam and notched his only Met save. The Mets had started the season in promising fashion, rising to six games above .500 on Memorial Day. They proceeded to fall out of contention with a thud, but they did just beat the almost as lousy as them Cubs, and maybe, despite a 50-65 record, they could recover some momentum for the stretch drive. At the very least, maybe they could sweep this twinbill and make a move on respectability. But they lost the nightcap, then all nine games of their near-West road trip through Cincinnati, Atlanta and Houston, mounting a losing streak that would remain unabated as I made my own stretch drive from Long Island to Tampa to begin my sophomore year at the University of South Florida. After three days of classes, the Mets’ season victory total stayed stuck on 50. Their defeat total was up to 80. They executed a fifteen-game skid that washed away the residual vibes of not just 1982’s flashy start, but all that “Magic” stuff from ’80 and ’81. But, man, didn’t Bob Murphy sound great while I washed my car?

48. 2009

What could go wrong did go wrong Metwise in the first year of Citi Field, a place I found myself resenting more with every visit. I was still mourning the passing of beloved Shea Stadium, and the team inhabiting its successor facility wasn’t distracting me with great play. I’ll say this for the new joint: it had superb food and was brimming with retail. That may not have jibed with purist instincts (“it’s more like a mall,” was a common refrain), but inside the sprawling team store within the Jackie Robinson Rotunda, there was a cap that caught my eye. It was a modern take on the late 1970s “Superstripe” model. The Superstripe caps were regularly advertised in Baseball Digest and other indispensable periodicals of the day. They were produced for all teams in all major sports, including the Mets, and I had a Mets version. There was no mistaking what team it represented as their name was spelled out amid the striping. A white mesh back, adjustable sizing, not particularly well made, but I appreciated that it was made at all, seeing as how the print ads never spotlighted the Mets. Three decades later, the Sunday before the All-Star break, the cap beckoned to me as I browsed pregame. I tried to ignore its siren song of nostalgia for my youth, as it was kind of pricey (what wasn’t at Citi Field in 2009?), but I couldn’t get it out of my mind. Come the seventh-inning stretch, I slipped away from Promenade, tromped down those endless flights of stairs that were no aesthetic match for Shea’s ramps and made my purchase. The 2009 version of the Superstripe cap was a quality item. Almost too well made, but it was objectively better than my long-gone 1978 cap. The back was blue. The bill was orange. It was fitted. The “NY” in the middle of “NEW YORK” and “METS” was prominent enough to be discerned coming down the block. It became my game cap of record for the next decade, the one I took the most relish in grabbing as I headed out to catch my westbound train. I still wear it to Citi Field once or twice a year. I don’t resent the not so new ballpark any longer. I got my favorite cap there.

47. 2023

The most recent spate of Met misery didn’t prevent me from finding my way to Flushing on thirteen separate occasions, sometimes as something approximating working press, sometimes on a solo mission of the soul, but mostly to meet up with a really good friend. As these meetups begat more meetups, despite the Mets having given up the ghost of competing for a playoff berth, it occurred to me that this person I was having a good time sitting next to would also make a splendid lunch or dinner companion, and we could have very well done that today or tonight. Yet I knew this — going to see the Mets, even the 2023 Mets — was better. I wasn’t watching the game as closely as I would have had I been focused on it at home, but how closely did this team need to be watched? And me and whoever, we weren’t face to face much in the course of the couple of hours we were together, because we were looking at the Mets rather than each other, but we could hear each other fine, at least when the Citi Field A/V squad wasn’t urging everybody to GET LOUD. “A hot dog just doesn’t taste right without a ballgame in front of it,” Charlie Brown once declared. I’d add friendship tastes even better with a ballgame in front of it.

46. 2017

The Mets won the pennant in 2015, returned to the playoffs in 2016 and got off to a roaring start in 2017. All they had to do was keep roaring, and everything was going to be fantastic. The last legitimate roar came from the bat of Travis d’Arnaud on April 13, when our catcher conked Adam Conley with a sixteenth-inning leadoff homer at Marlins Park to give the Mets a 9-8 lead, an edge the skyward-pointer himself, Hansel Robles, preserved in the bottom of the frame. It was a long night (5:38), one that I snoozed through a bit of, but I woke up in time to see it won. The Mets, on a five-game winning streak, were 7-3. The bad Marlin juju we bake into our expectations hadn’t derailed them. Marcell Ozuna’s grand slam off Robert Gsellman way back in the first inning hadn’t buried them. They came right back with four runs in the top of the second, two in the top of third and one more in the top of the fifth. Yoenis Cespedes hit two out of that Miami monstrosity. Gsellman and Josh Edgin didn’t maintain the lead, but Michael Conforto got it back for us in the eighth. Then eight more innings, or as many as were required to get to 9-8 on the scoreboard and 7-3 in the standings. This was both sincerely appreciated and reasonably anticipated. The Mets of 2015 and 2016 and now 2017 were the payoff for all those dismal years of muddling in place. I truly believed we were ensconced in a legitimate era of Met success. The Mets lost ten of their next eleven, twenty of their next twenty-nine and finished 70-92. They’ve swerved in and out of eras every few months since that night in April of 2017. That’s the era I wish had kept going. It felt like a pretty good place to put down roots.

45. 1974

The kid’s name was Hal. His last name began with a P. I can’t quite remember what it was. It doesn’t matter. To me, he was Hal with the wristbands. This was during day camp in Oceanside, in July of a year when the Mets would definitively not repeat their success of 1973, and on the night before, Hal had gone to the Mets game. He mentioned it casually. Or maybe he announced his presence with authority. Whatever he didn’t say was there on his wrists. He was wearing Mets wristbands, acquired at Shea Stadium the night before, when he was at the game. I wasn’t so much envious of Hal with the wristbands — certainly not for the wristbands themselves — but I admired like hell his off-hours activity. As of that July day in 1974, I had been to two Mets games, once via the day camp I attended the previous summer, once with my older sister and a friend of hers a few Saturday afternoons prior. They were extremely special occasions that had to be carefully planned, either by enrolling at a camp or perusing the schedule and agreeing on a date. Yet here was Hal and his wristbands casually confirming he went to see the Mets on a weeknight. I’d heard of such things, the idea that somebody would decide to go to a game and just go. I don’t know how the decision was executed in Hal’s household, yet as far as I could tell, it was no big deal, wristbands or no wristbands. “I went to the game last night” was something I now wanted to be able to say like it was something I actually did. Eventually I would. I wouldn’t walk around the next day with any goddamn wristbands on. C’mon, Hal. Act like you’ve been there before.

44. 2020

In September, when I hadn’t been on a train except for the briefest of local hops since February, I considered boarding the LIRR and taking it to Woodside just like I would in any September, then switching for the 7 to Mets-Willets Point, also a familiar maneuver. I was going to get off the elevated line, walk downstairs, find a bench or lean against a post and turn my radio on to listen to the Mets play the Rays a few hundred feet away. I couldn’t go into Citi Field, as no fan could go into Citi Field while a pandemic was in progress and no vaccine for it was available. I understood I couldn’t go inside a ballpark. I watched the action on TV once it started up in late July, the very essence of better than nothing. Nothing was the attendance at every game, unless you counted those eerie corrugated cutouts, which I didn’t. Still, on September 23, I debated with myself the necessity to get as close as I could to the final home game of the regular season because I always went to the final home game of the regular season. I had an active 25-year Closing Day streak, dating from 1995 forward. It would necessarily hit pause in 2020, but shouldn’t I do something to spiritually keep it going? I ended up not acting on the impulse, safety being the better part of whatever while COVID lurked behind every corner. I picked up the Closing Day streak the next season and have kept it going ever since; it comes with a semi-colon now (1995-2019; 2021-Present). Once in a while, I picture myself taking that 2020 trip for the streak’s sake. It was a silly notion, but not inconceivable to a fan like me.

The final regularly scheduled edition of National League Town is available for your listening pleasure on Spotify and other podcast platforms. Pop it on, as the people who say things like that like to say.

Happy birthday Greg! And thank you. Thank you for this important part of our fandom. All the best for 2024 (Year of the Dragon).

Thank you, Seth. May we not be, uh, draggin’ in ’24.

Happy birthday, and tell me more about the Emerald Society Pipe and Drum Band warming up for Bob Hope.

Thank you. They were…pervasive.

Love the Peanuts cartoon, Greg.

How TRUE it is!

And Happy Birthday, as always!

And Ya Gotta Believe More in ’74.

Thanks, Eric. Believe we shall.

Sounds like you and Hebner each reached your performing heights right around the same time.

“On with the Show, This is It!”

One of us sensed when it was time to step aside.

I am so impressed with your recall, research of Mets seasons, games and players – never CBmind so much of the ‘atmospherte’ thstcaccompanies a season. For all my love of the Mets so much of it blurs aftercaxwhkk I’llle ! Thanks so much for this portion of a list. Hope you getcstoundctonsharingvthecrest over the next year. Happy Birthday and Happy new year! LGM!

Glad you enjoyed it, Ed. Thank you.