For those keeping adjustable score of very recent, relatively quiet Met offseason acquisitions at home, you can pencil in the following:

Righthanded pitcher Yuhi Sako.

A southpaw counterpart named Brandon Waddell.

Jared Young, who plays first.

Catcher Chris Williams.

Righty Griffin Canning, who maddeningly contained Met bats one day last summer, so I can say, “Him I’ve heard of.”

If you penciled in onetime All-Star reliever Alex Reyes, erase him. The lately inactive ex-Cardinal was reported in small circles to have signed with the Mets ahead of next year, but that report — too random not to be true, you’d figure — was apparently erroneous. Also, it turns out Alex was an unannounced member of the Met organization last year, never gathering notice for a good reason: he never pitched. He hasn’t pitched since 2021. The whole thing, disseminated and debunked in a matter of Internet hours, at least kept roster-watchers engaged before the Canning news came down a credible pipeline.

Collectively, this gang of gets, with or without Alex Reyes, doesn’t have quite the same zing to it as the individual Met offseason acquisition about whom word spread like wildfire almost two weeks ago, do they? Yeah, it’s gonna be hard to punch up the list of Met offseason acquisitions with quite as much as oomph as was done for outfielder Juan Soto.

Still…Juan Soto! That happened! Physicals got passed! Conferences got pressed! Jerseys with legible lettering got donned over street clothes! Baseball players wear clothes on the street you can’t wear on the field. Baseball fans wear clothes baseball players wear on the field. We’re all considering an expansion to our wardrobe. We all look sharp in 22.

Photoshop, et al, saw us through the unofficial period, when we knew we’d landed a star but it couldn’t be confirmed by the club. The anticipant got creative placing the “reported” acquisition in his correct threads before he could try them on. Who could wait for it to become official? Then it became official, and it’s still official. Juan Soto became a New York Met last week, and Juan Soto is still a New York Met. It bears repeating. We’re slated to repeat it for the next fifteen years. Might as well get used to saying it.

Before Cohen, the Mets were habitual HA! magnets. In February 2004, the Mets signed a lefty with a touch of big league experience, Randy Keisler. It’s what teams do as Spring Training approaches. “He has a track record in the majors and we liked what we saw of him at a tryout,” was GM Jim Duquette’s qualified endorsement. “We’ll see what develops.” Turns out nothing developed; despite Duquette’s low-ceiling projections. Keisler, who claimed some local experience, only made it as far as the Norfolk Tides before moving on.

Thing was, the Mets were ready to announce this most minor of moves the same day another team in New York had something to say about another transaction. The Yankees were introducing Alex Rodriguez. “Majors feel shock wave of Yank deal,” heralded the Courier-News in New Jersey, amplifying in its article’s subhed, “Mets answer with signing of ex-Yankee Randy Keisler.” In a small box adjacent to a large picture of the new third baseman in town posing for the cameras ran this headline in Newsday: “Mets Also Add A New Player”. The brief accompanying story led with, “Talk about teams headed in different directions.”

Nah, that’s OK, though to their self-aware credit, according to the Star-Ledger, the Mets issued their news in an e-mail headlined, “Alex Who?”

One of the first (of many) thoughts to pass through my head on the Sunday night we got Soto was the news broke while the NFL was filling a prime time window, much as was the case when we got Carter. Then it was Monday Night Football. Then it took players — Hubie Brooks, Mike Fitzgerald, Herm Winningham and Floyd Youmans — as much as a commitment of currency to land a superstar in Flushing, but let’s not overlook the financial aspect of getting Gary Carter on December 10, 1984. “Carter’s stats last year,” Channel 5 sports anchor Tom McDonald gushed the night the deal went down, “showed why he’s paid $2 million a season.”

One of the first (of many) thoughts to pass through my head on the Sunday night we got Soto was the news broke while the NFL was filling a prime time window, much as was the case when we got Carter. Then it was Monday Night Football. Then it took players — Hubie Brooks, Mike Fitzgerald, Herm Winningham and Floyd Youmans — as much as a commitment of currency to land a superstar in Flushing, but let’s not overlook the financial aspect of getting Gary Carter on December 10, 1984. “Carter’s stats last year,” Channel 5 sports anchor Tom McDonald gushed the night the deal went down, “showed why he’s paid $2 million a season.”

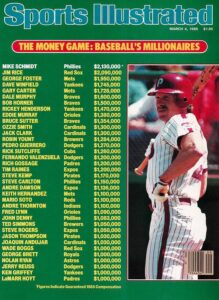

Baseball media’s fascination with how much top-flight baseball players make isn’t new, just as the press is pretty blasé about how much baseball franchise owners who aren’t Steve Cohen often aren’t spending to make their teams better. Sports Illustrated during Carter’s first Spring Training as a Met made “The Money Game: Baseball’s Millionaires” a cover story. Most of the cover art was a list of players guaranteed a million bucks or more in 1985. Gary Carter was listed fifth, two slots behind George Foster. Down the line some was Keith Hernandez. Three Mets had seven figures coming their way.

And the Mets won 98 games. Sometimes investing in players pays.

And the Mets won 98 games. Sometimes investing in players pays.

Soto is coming to a Mets team that just competed in the NLCS. Carter was coming to a Mets team that had just won 90 games. Beltran was coming to a Mets team wallowing beneath .500 and thirsting for a savior. If they were one or two players away following 2004, those players might as well have been (to steal a line from Dick Young) Babe Ruth and Walter Johnson. We settled for Pedro Martinez and Carlos Beltran.

Nice settlement. Pedro, 33, was a legend, if edging into inevitable creakiness. Nonetheless, we were very happy to have him as our ace in the moment. Carlos, not quite 28, we were over the stratosphere about. He was a multitalented player, all his tools having been on display in the spotlight of the most recent NLCS. That’s where he carried the Astros to the lip of the World Series. That’s where his price tag rose. The Astros would have liked to have kept him. The Mets wanted him more, as in they’d pay more. The Houston offer was a reported seven years, $105 million. The Mets’ terms were same length, $119 million. The Yankees may have been given a chance to swoop in and get in our way, but they abstained, chasing Randy Johnson instead that winter and deciding they could throw only so much monetary weight around. All at once, Carlos Beltran looked at his options and decided he had always wanted to be a New York Met.

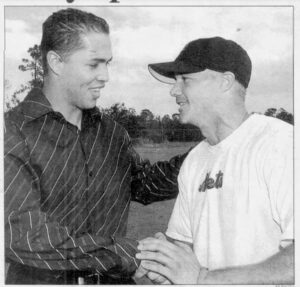

Taking in Soto’s delightfully substance-free presser (I don’t particularly care whether any of his erstwhile teammates rang him up while he was being courted), I remembered what a big deal it felt like that when Beltran was introduced, he said that he chose this downtrodden club of ours because under Omar Minaya and Willie Randolph and infused by their will to win, they were now “the New Mets”. Loved the hype. Loved watching Beltran arrive in St. Lucie a couple of days later for the team’s mini-camp, a passing rite of January, as if he couldn’t wait to whip this organization into shape and remold it in his own awesome image.

That wasn’t really Beltran’s personality. What did we know from Beltran’s personality? He’d been in Kansas City from 1998 until a month or so before 2004’s trade deadline, the essence of toiling in obscurity. Then he burst upon the postseason. We knew he was good. Suddenly it was clear he was great. Wouldn’t it be something if he was transformative, too? Yet Beltran’s vibe was far different from Martinez’s. Pedro, long an emblematic baseball figure, took over everything about the Mets to the extent he could in 2005. Of course he did. You didn’t need to be a Red Sox fan to know loads about Pedro Martinez. Wherever he went, it was going to be a scene. Low-key Carlos’s best public intentions would need a while to catch up to his inner capabilities. It was all right. There was only one Pedro Martinez.

That wasn’t really Beltran’s personality. What did we know from Beltran’s personality? He’d been in Kansas City from 1998 until a month or so before 2004’s trade deadline, the essence of toiling in obscurity. Then he burst upon the postseason. We knew he was good. Suddenly it was clear he was great. Wouldn’t it be something if he was transformative, too? Yet Beltran’s vibe was far different from Martinez’s. Pedro, long an emblematic baseball figure, took over everything about the Mets to the extent he could in 2005. Of course he did. You didn’t need to be a Red Sox fan to know loads about Pedro Martinez. Wherever he went, it was going to be a scene. Low-key Carlos’s best public intentions would need a while to catch up to his inner capabilities. It was all right. There was only one Pedro Martinez.

After 2005, Beltran grew into his leadership role, definitely modeling a formidable veteran presence over time. And he sure went about hitting and fielding once he grew comfortable in New York. But I think we expected the sun and the moon out of a star, to his initial detriment. The superstar required a wingman to produce to his potential. Most superstars do. Beltran didn’t have a Hernandez and Strawberry to take the pressure off the way Carter did, not until Delgado came aboard, and Wright was a year older. Soto has a Lindor. We all have a Lindor, thank goodness. No new saviors necessary this winter. One took up residence here in 2021, even if it took a while to realize we had one…and it took a while for Lindor to realize how to best execute his saviorship.

“Nah,” the Mets forced themselves to decide. “We can get Piazza. We gotta get Piazza. We got Piazza.” Then, despite the 1998 aspect of the equation not adding up in terms of earning a playoff berth (not Mike’s doing; he was on fire in September), the Mets convinced Piazza to stick around from 1999 through 2005. Seven years and $91 million would make any person realize how much they liked a particular place, though one assumes the money was gonna be somewhere if Mike wanted to seek it. He liked his new surroundings enough to make them semi-permanent. There’d be a year in San Diego and a year in Oakland much later, but check out the cap on his Hall of Fame plaque. He’s been a New York Met forever since 1998, and the New York Mets are forever better off for it.

The Mets even managed to pool enough dough to lure free agents Robin Ventura and Rickey Henderson onto their roster for 1999, and the hunt for the playoffs remained in full effect. Still, you always felt back then if you attracted hitters, you might not be able to pay pitchers. Little Dutch Boy finger-in-the-dike stuff. I don’t know if that was true. I don’t believe we’re gonna have to worry about prioritizing with Steve Cohen involved.

Juan Soto had a helluva year in those other pinstripes, his only year in that outfit. Won his way station a pennant with a dramatic swing. Then he was ready to exit stage Boras and pursue free agency. Sound like anybody we knew for one year once?

Mike Hampton is the answer I’m looking for. Mike Hampton was a top-flight pitcher (22-4) for whom the Mets traded to advance them further into the postseason than they’d gone the year before. It worked. The 1999 NLCS runners-up won the National League championship in 2000. Hampton threw a three-hit shutout to clinch it. Won the MVP of his signature series. Yet Hampton ultimately viewed New York (NL) as his way station between trade and free agency. The Mets offered him a nice contract to put down roots (just as Houston offered such a deal to Beltran). Colorado offered him a nicer one. He took Colorado’s. Even with the infamous “schools” remark, I didn’t take it as an affront. Business brought Hampton to Shea. Business sent him to Denver.

The Soto business is something every team should have sought getting in. The Mets got in. The Yankees wanted to stay in. The Mets prevailed. Technically, we got a Yankee. Really, we got a player. I could see the “how could he leave the Bronx?” angle when Bernie Williams nearly left that crew for Boston between 1998 and 1999. Williams had been there his entire decorated career. Soto was just passing through. It happens every winter.

What better way to prove seriousness than go after the Carlos Beltran of his time? Dave Winfield of the Padres had five tools and the All-American audacity to cash in. The Mets were signaling they planned to be a legitimate entry in the National League for years to come. The Mets under M. Donald Grant sat out the Reggie Jackson sweepstakes and wouldn’t even shop the less pricey aisle and make a real move to lure Gary Matthews in the first year of free agency. Matthews wasn’t a megastar, but he was, in his day, a potential stalwart for a team dedicated to staying above .500, which is where the Mets had maintained residence every year but one since 1969. Tom Seaver wanted the Mets to pursue Matthews. But why would Grant care what his franchise pitcher had to say about elevating the team behind him?

That was 1976 going into 1977 going into the depths. Nineteen Eighty going into 1981 could have represented another step out of hell. A giant leap. The new, enlightened owners were in place. The savvy GM was in place. Traces of talent were in evidence. Now, let’s go get Dave Winfield! The Mets put a reported eight years on the table, a total of $12 million, the psychic equivalent of $765 million over fifteen years then. The entire Metropolitan Baseball Club of New York went for $21.1 million the January before. Winfield could have taken it and taken over a metropolis. He could have stayed in the league he knew and not have to learn new strike zones (this was a concern in those days). He was interested enough to seek assurance from the Mets that he wouldn’t be the extent of the 67-95 ballclub’s reclamation project. Cardinal first baseman Keith Hernandez, a year removed from his co-MVP season, was mentioned as a potential trade target. The pieces were within grasp to create a beautiful marriage.

“It seems to have come down to the Mets and the Yankees,” wrote up and coming Daily News columnist Mike Lupica on December 5, “the first-ever New York, New York confrontation in the marketplace. The Mets need to win this fight. They need to prove to their starving fans that they are some good guys who can win. The Mets have to scrape together a deal at the winter meetings, show Winfield that they mean business. Then they must offer him enough money to keep him in the National League while still bringing him to New York. This is how the Mets can bring National League baseball back to New York.”

George Steinbrenner, implicit in Lupica’s calculation as the opposite of a good guy, came in with more years and more money. Winfield would learn the American League strike zone. He’d also watch the next ticker-tape parade bestowed on a New York World Series champion on television, and not because he overslept it. You wouldn’t have known when the Yankees beat the Mets to Dave Winfield in December 1980 how much New York was about to be enjoying National League baseball in a few short years. A painful interregnum bridging the darkness of de Roulet and the brilliance of Doc & Darryl had to be endured first, but the lights would switch on soon enough.

Dave Winfield might have fit the description of generational ballplayer, a phrase thrown around to identify Juan Soto. By definition, not too many of those come around. Perhaps that’s why the Mets, under their “good guy” ownership of Doubleday and Wilpon for the balance of the occasionally collusive 1980s, didn’t go after big-time free agents. But they did put their resources to work for the betterment of their ballclub. Traded in 1982 for George Foster and extended him for what a player of his caliber (which was high) was worth. Traded in 1983 for Keith Hernandez and then paid him a handsome sum to keep him from contemplating a way out. Assumed Gary Carter’s contract, a substantial package, when they gave up four players to land him in 1984. Nurtured their farm system all the while. The Mets who hadn’t known what to do with free agency when it started became the Mets who worked well within the system that included free agency — without necessarily dipping directly into free agent waters. In between their Grant incarnation starving us and their Cashen incarnation sating us, they attempted to harpoon one offseason’s biggest whale. Their spear was impressive, just not the most effective in the competition.

To counter that notion, I bring you Terry’s guest from that June episode, Howie Rose, who’s been hip to everything about New York baseball since 1961, the year he first started watching. He had twice as much to watch within a year of his introduction, all of which he brought to bear when answering a listener’s e-mailed question about what makes Mets fans unique, especially in light of “their neighbors” having so many championships to crow about.

Howie’s entire answer seems worth repeating all these months later.

“There is a unique identity to the Mets, and younger fans cannot possibly understand what the Mets meant in New York from their very beginning in 1962. You know, the Yankees had just come off of one of the great years in baseball history, 1961. But remember now, there were two fan bases that were disenfranchised when the Dodgers and the Giants left just five years before the Mets played their first game. So whereas you might have thought that with no National League baseball in New York, a lot of those fans would have gravitated to the Yankees, that wasn’t the case. The Yankees’ attendance for those four interim years was flat. They didn’t get any more fans because the Dodgers and Giants left.

“So the creation of the Mets was cause for major celebration. Casey Stengel did an incredible job of selling that team. And even though the Yankees were champions, the Mets, to a large extent, owned New York, even during some of those great years for the Yankees, and then on through until 1969, when the miracle of baseball miracles took place, and comparatively you could not find a Yankee article in the newspapers back in those days, the Mets had such a stranglehold on the city, as they did in the 1980s as well.

“So this whole business about the Mets being the little kid brother to the Yankees could not be anything further from the truth historically. If it’s been lately, that mindset needs to change, and I think under this ownership [it’s going to].”

The Yankees responded to losing Soto by signing Max Fried — thanks for taking him off the NL East’s hands — and trading for Devin Williams and Cody Bellinger. They’ll still spear their share of whales. But so will we. Even if we hadn’t gotten Juan Soto, the fact that Steve Cohen had gone after him with every intention of making it happen filled me with confidence. If not Soto, I figured, then somebody else to fill another need. We won’t be out on anybody we want to be in on.

Had free agency existed in 1962, I imagine that’s how Mrs. Payson would have played things. She wasn’t looking to bring anybody’s “little brother” into this world, let alone this town.

One sentence in a press release, and that was all I heard or read regarding “Mets” and “culture” this offseason. Every offseason since I don’t remember when has included a press conference in which an owner, a general manager or a manager hailed the culture that was being planned to change the New York Mets from whatever was wrong with them to whatever was going to make them less incorrect. You sort of want to believe it the first time you hear it. Hearing it too many winters tends to frost your windshield.

This offseason, after the playoffs, after the lovin’, in sync with the Soto, it’s one sentence, attributed to the president of baseball operations who doesn’t have to talk up the culture. We all experienced it for real from June on. We’re willing to trust David Stearns to build on what’s been started rather than promise to construct another from scratch.

Not that we wouldn’t like a little more to add to Soto besides Yuhi Sako, Brandon Waddell, Jared Young, Chris Williams and Griffin Canning, if not Alex Reyes.

Each winning team creates its own groove, though some notes resonate through the years. At heart, we’re scrappy as hell. In reality, our culture values signing superstars to fifteen-year contracts paying $765 million. Mets made money in 2024, too, but you’d be forgiven if you believed they were playing ball for the fun of it.

The Soto signing nudged 2024 ever so gently into the past. It happens one way or another when every calendar nears its end. The start of something big rather than a one-off blast is how we hope to recall 2024, meaning 2025 picks up where 2024 leaves off, and lord help it if another 22-33 start befalls us. Newsday reports hotcakes aren’t selling as speedily as tickets to see Soto and associates: “According to the Mets, it took 45 minutes on December 9 for the club to sell more tickets than it did on the entire first day of sales for the 2024 season.” Consumer patience ain’t what it used to be, so a blitz from Opening Day forward is advised.

Though if we require another late-season surge to burst through the gates of October, it will no doubt only add to the legend of those Amazin’, Amazin’, Amazin’, Amazin’ Mets.

But there’s an easier way to crown a new all-time Mets home run champ. Sign the guy who’s twenty-six homers away. Pete Alonso’s 226 are so close to Strawberry’s 252 that we can taste it. It’s absolutely Arctic. C’mon, the Polar Bear can’t be permitted to stray from his natural habitat, not when he’s so close and we’ve got a core that won’t be the same without him. It’s like imagining the Washington Nationals without Bryce Harper or the Baltimore Orioles without Manny Machado.

Or any number of teams who grow their own stars but see them leave for greener pastures. The Nats (with Soto) went on to win a World Series sans Harper, with whom Washington stuck until free agency struck. The Orioles’ endless rebuild picked up genuine steam a few years after Machado, traded to L.A. before he could walk away altogether. Your results may vary. I’m not yet fully prepared to reckon with the other side of baseball’s free market, but it’s beginning to occur to me it’s a possibility Alonso wanders off, despite there being no pastures greener than Steve Cohen’s. Maybe Pete sees a better situation for himself somewhere else. Maybe Stearns sees a long game whose outcome works better with another first baseman and premier slugger in Pete’s stead. I see a lifetime Met who, good health willing, will swat in the neighborhood of 400 homers as a Met. I don’t want to see him go away.

Except for the good health element, we never had these problems with David Wright, who was a cinch to pass Darryl had we not all been compelled to Google stenosis. Yet another reminder that one never knows how anything works out.

At least you can have a hunch that they’ll work out better when you’ve got Cohen, Stearns and Soto all on your side. Maybe that’s 2024 going on 2025 talking. I don’t have worst-case scenarios in me right now.

“…two fan bases that were disenfranchised when the Dodgers and the Giants left…”

Wow, that’s a literal definition of disenfranchise! I can’t imagine how heartbreaking those departures must have been. I kind of wonder how NY let that happen.

How did New York let that happen? One name – Robert Moses

Number 22? OMG. That doesn’t feel right. For 55(?) years that number has meant one thing to me – Donn Clendenon – one of the least remembered crucial players on the team in ‘69. That number may not be be hanging from the rafters but in my heart it’s retired. I do not think ‘69 happens without Clendenon being there, both for his bat and his veteran leadership. Okay, yes, but Al Leiter earned the number.

As for Soto and Carter comparison – No. Eh, eh. That was already a complete team. Getting Carter, turned it from a very good team to a special team. The team we have now has a pitching staff in shambles, aside from closer. We gained 41 HRs but as of this moment we’ve lost 34 HRs. If the Mets don’t re-sign Pete or replace his HRs and RBIs then what was the point of signing Soto? And as you alluded to, if Alonso is on-board then the season will be energized for player and fans as we count down homers to the Mets record, with Darryl’s Met celebrity becoming reinvigorated. A repeat of ‘85 Mets? I’m worrying about a repeat of the ‘92 Worst Team Money Can Buy Mets. If I sound like a long time brutalized by fate, pessimistic Mets fan it’s only because I’m a long time brutalized by fate, pessimistic Mets fan.

And why the heck haven’t they picked up Jose Iglesias?

I guess in this case, Juan flew OUT of the cuckoo’s nest.

Absolutely LOVE the 1974-style Soto card. Back then, they only said TRADED, but LOVE the ‘SIGNED’ affixed to the bottom.

Let’s hope in 4 or 5 years we are not begging Soto opts out. He doesn’t look like he’s missed too many meals lately, and he IS only a 2-tool player. And he will supposedly be 31, just in time for the downswing.

With the Yankees signing Goldie the Alonso plot thickens.

To me there are only 2 reasonable paths to take. One is to sign Pete.

The other is Alex Bregman, move Vientos to first. Would Pete DH? Probably not.

Sentimental me wants Pete even though, the way his hitting has dropped and his strikeouts gone up I’d give no better than 50% odds that he breaks our HR mark in 2025.

But when I get analytical getting a gold glove at third and giving up weak defense at first makes us a better team. And Bregman’s batting numbers have held up the last couple of years though he’ll be 31 next season so who knows.

I guess we’ll see. Do wish we’d start picking up guys who could be 2/3 starters, not competing for the 5th spot.

I can think of one other time the Mets and Yankees went head to head over a free agent. That was Curtis Granderson. So this is not the first time we beat them out, although it’s obviously the biggest. I didn’t remember that the Mets went after Winfield, though. One has to wonder what the Mets would have been like with Winfield, Foster, Hernandez, Strawberry and Carter all in the same lineup at the same time. We may have won a few more Series with those guys.

Foster was shot, but we certainly would have had the best record in May.

Truly sorry to hear about Rickey, only 65.

His mentor, Billy Martin, died on Rickey’s birthday, at 61, which happened to be Christmas Day.

Rickey’s now at that big card table in the sky.

Manaea’s coming back, 3 years, $75m. I guess the team believes the 2nd half of last season was real. I’m on board with that.

They just took another one of our heroes, Jack DiLauro.

R.I.P., my friend.

But its not really official until we hear it from Greg.