The Mets, it was established when they were established, represented the New Breed. Their fans were descended from a tradition of Giants and Dodgers, but they — we — were something else altogether. We were not the past. We were the present and, by implication, the future. We were the stuff of 1962 when 1962 was as cutting edge as it could get. Everything about our existence shouted PROGRESS! as much as it roared LET’S GO METS!

That’s why I find it incongruous when a direct link can be forged to something old, musty and unmissed. If the Mets were all about the new, how old could they be?

In the case of five Mets, pretty old. And very unmissed.

Four players who wore the Mets uniform in the early years of the franchise as well as one extraordinary player who wore it when the team was approaching adolescence had previously worn uniforms that were no longer in style when the Mets came to be. They were the uniforms of the Indianapolis Clowns, the Kansas City Monarchs, the Atlanta Black Crackers and the Birmingham Black Barons.

Five Mets played in the Negro Leagues.

Maybe in 1962, while civil rights legislation still awaited its mighty push, this didn’t seem so anachronistic. It had been only sixteen years since Jackie Robinson broke the minor league color line with the Montreal Royals, fifteen years since he took it a step further with the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Cleveland Indians, St. Louis Browns and New York Giants were all integrated by the end of the 1940s, though by integrated, we mean no more than a few African-American players joining the white players. Even the most “progressive” organizations weren’t flinging open the doors to everyone regardless of race. Quotas kept the number of black players to a handful throughout the Fifties, and no team dared field as many as five black players at the same time, lest fans do the math and figure a majority of their team at a given moment wasn’t white.

And those were the progressive organizations. Several took their not-so-sweet time signing any black players at all. The Boston Braves and Chicago White Sox became the fifth and sixth franchises to include a black player in 1950 and ’51, respectively. More than six years had to pass between Robinson’s April 15, 1947 debut with Brooklyn before the Philadelphia A’s and the Chicago Cubs got on board in 1953. It was barely a month before Brown v. Board of Education was handed down on May 17, 1954 that the Pittsburgh Pirates, the St. Louis Cardinals and the Cincinnati Reds deigned to field a team that wasn’t wholly white.

The highest court in the land struck down “separate but equal,” yet five major league baseball teams clung to separate beyond Brown. No black Washington Senator played until September 1954; no black New York Yankee played until 1955; no black Philadelphia Phillie played until 1957; no black Detroit Tiger played until 1958; and no black Boston Red Sock played until July 21, 1959. That was a dozen years after Jackie Robinson became a Dodger, nearly three years after Jackie Robinson retired.

Who was the first black Met? Beautifully, that’s never been an issue. By 1962, there was no color line to break. The expansion teams were integrated from their beginning, the Mets included. The first three batters the Mets sent to the plate on April 11, 1962 were, for the record, Richie Ashburn, Felix Mantilla and Charlie Neal — a white man from Nebraska, a Latin man from Puerto Rico and a black man from Texas.

They were all Mets is all that mattered.

But let’s not kid ourselves. Brown v. Board of Education didn’t erase discrimination in this country any more than Jackie Robinson erased all vestiges of racism in baseball. Likewise, the matter-of-fact integration of the New York Mets, the Houston Colt .45s, the Los Angeles Angels and the second edition of the Washington Senators (the first one having vamoosed to Minnesota partly for reasons of race, by owner Calvin Griffith’s ineloquent reckoning), didn’t signify that everything was equal for everybody everywhere. The 1962 Mets trained in St. Petersburg, a southern city by dint of more than geography. The big Spring Training hotel in town then was the Soreno. It was where the Cardinals stayed and where the Yankees had stayed before they moved to Fort Lauderdale. The Mets planned on making it their base, too, but as a Newsday article from 1987 noted, “the Soreno Hotel wouldn’t take their black players, so the entire team stayed at an unrestricted hotel inconveniently located on St. Petersburg Beach.”

The team’s new place, the Colonial Inn, wasn’t an unalloyed bastion of equality. As recounted by Janet Paskin in Tales From the 1962 New York Mets, Al Jackson was “greeted by the vestiges of segregated Florida” upon arriving at the Colonial, namely a “request” from the hotel manager that Jackson, while certainly welcome to sleep in his room, stay out of the restaurant, the bar and the pool.

“I thought, ‘I’ll be damned,'” Jackson told Steve Jacobson in Carrying Jackie’s Torch. Mets traveling secretary Lou Niss “raised hell,” but to only partial avail. Mets players — black or white — who stayed at the Colonial would eat in their own private dining room and, by club edict, avoid the hotel bar altogether. It wasn’t a perfect arrangement by any means, but it was the Mets’ clumsy way of saying everybody here is a Met, not a black Met, not a white Met. Just a Met.

“I guess if the blacks couldn’t go in the restaurant,” Jackson recalled to Paskin, “the white guys couldn’t go in either.”

We were a long way from Utopia in 1962; we’re a long way from it now, too, but can you imagine having players on the Mets whose baseball backgrounds included a stint in a league that was identified by race? A league that no matter how great the level of competition may have been — and it’s generally considered to have been major league — existed because custom and law dictated it?

Yet it was so in 1962 and 1963 and 1964 and 1966 and as late as 1972 and 1973. Five Mets began their professional baseball careers as Negro Leaguers.

• The third batter and first second baseman in Mets history, Charlie Neal? He was one of those ex-Dodgers the early Mets had a predilection for collecting, but before he signed with Brooklyn and starred for the ’59 world champs in L.A., he had been an Atlanta Black Cracker.

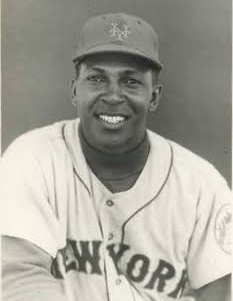

• The taciturn catcher whom we know mostly from Ralph Kiner’s timeless anecdote — “her name’s Mrs. Coleman and she likes me, Bub” — Choo Choo Coleman? Prior to his legendary answer regarding his wife’s name and “what’s she like?” he had been an Indianapolis Clown. (Update: In January 2012, Coleman told Nick Diunte of examiner.com that the Clowns with whom he played in 1956 and 1957 was a touring club not affiliated with any specific league.)

• The One-Year Wonder who started in right field in the very first game at Shea Stadium, George Altman? Before flanking Jim Hickman on April 17, 1964, he had been a Kansas City Monarch.

• The Say Hey Kid who electrified Shea upon his return in 1972 and drove it to tears by saying “Goodbye to America” in 1973? Willie Mays? Willie, perhaps the greatest player to ever wear any uniform, became a big league ballplayer for the first time as much with the Birmingham Black Barons as with the New York Giants.

Mays, as recounted in James Hirsch’s wonderful biography, was definitely a product of the Negro League, technically the Negro American League, the one that continued to operate for more than a decade after Jackie Robinson began to render segregated baseball obsolete. Hirsch describes Mays as a “new archetype,” blending speed and power as it had not been combined by previous superstars.

His base-stealing skills had developed out of necessity. There, most squads had fewer than twenty members, so versatility was required, and pinch runners were an unaffordable luxury.

[…]

Stolen bases were the easiest way to quantify Mays’s running skills, but he also accumulated extra bases through speed, cunning and force of will. In this area, more than any other, he imported the Negro League philosophy of daring, exuberance and pugnacity.

Willie Mays was the last Met to have Negro League experience in his background and the penultimate major leaguer to have played in such a circuit (the last was Hank Aaron, who retired in 1976). There was no more Negro League baseball after 1960, so any of its veterans who made the Mets were necessarily young when they played in those generally overlooked uniforms. There were still onerous quotas to stretch and stubborn barriers that had to crumble as they were coming up, but men like Neal, Coleman, Altman and Mays had more opportunity than the generation that preceded them.

A fifth player who shared the Negro League pedigree with those four Mets was Sammy Drake, an ostensibly unremarkable member of the remarkably bad 1962 Mets. Drake was an expansion draft choice of the Mets in October 1961, but didn’t make the club until the following August. He played in 25 games and registered 10 hits. The last of them led off the top of the eighth at Wrigley Field in the final game of the season. With Drake on first, Richie Ashburn singled. Then Joe Pignatano, later to earn a World Series ring as bullpen coach of the remarkably good 1969 Mets, hit into a fly ball 4-3-6 triple play. It was the last swing of Pignatano’s career. The last time Ashburn would be on the bases, too. Same for Drake. Their major league careers all ended that day, September 30, 1962.

I knew about Pignatano making his last big league at-bat overly memorable. I knew about Ashburn retiring after that 120th loss. I didn’t know about Drake, though. Until I looked it up, I had no idea he was one of the three outs. I didn’t know that he kept plugging away in the minors through 1965. Frankly, I knew next to nothing about Sammy Drake until last month when word of his death filtered onto the Internet a few weeks after he passed away at the age of 75. It was only then that I learned Drake, like Altman — and Satchel Paige, Ernie Banks and Jackie Robinson himself — was briefly, on a “tryout” basis in 1953, a Kansas City Monarch…a Monarch who would become a Met.

In an earlier time, he would have stayed a Monarch or maybe moved on to the Baltimore Elite Giants or Homestead Grays — or continued with the Carman Cardinals of Canada’s Mandak League, where he played in 1954. That would have been as far as Sammy Drake could have gone as a baseball player. But by the end of the ’54 season, with Brown v. Board of Education sinking into the American way of life with all deliberate speed, Drake signed with the Cubs. They sent him to the Single-A Macon Peaches of the South Atlantic League, or the Sally, in 1955. There had been Macon Peaches playing baseball in Georgia since early in the 20th century. It wasn’t until 1955, however, that there were black Macon Peaches. The first of them were Ernest Johnson and Sammy Drake.

It was eight years after Robinson. It was eleven months after Brown. It was a future Met making history in Macon seven years before he’d become one of ours.

There were no parades for this pioneer. As Drake told the Macon Telegraph in 2009, he and Johnson were limited to dining in a “little hole-in-the-wall restaurant there they had for us.” Macon and the Sally League of 1955 weren’t close to even the limited options permitted by St. Petersburg circa 1962. If you were Drake and Johnson, you stayed on the bus when your teammates got off to eat. They brought you your food and you ate it there.

“That was very degrading,” Drake told Coley Harvey of the Telegraph. “It hurt, man. It really did.”

That was just an element of a painful year in Macon, according to Drake’s recollections.

“It was the fans and the city itself where I had the problem,” Drake said. “It was the same way they treated Jackie Robinson. They threw black cats on the field, called me all out of my name and everything else. They called me the ‘N’-word, OK. They called me burr head. Or ‘black this, black that.’ And these are my home fans. I’m not talking about when I would be traveling to Savannah and all these other Southern cities.”

Sammy Drake moved on from Macon. He made the majors in 1960, with the Cubs, playing alongside Banks as well as his brother Solly (the Drakes were the first African-American brothers to play on the same major league team). Sammy got into 28 games with Chicago over two years before being drafted by the Mets. His last professional baseball experience was as a Buffalo Bison, amid an eclectic roster that included Choo Choo Coleman, first black Boston Red Sock Pumpsie Green, first Dominican major league shortstop Amado Samuel and champion Mets to be Cleon Jones and Bud Harrelson. In retirement, Sammy Drake taught Sunday school at the Greater Ebenezer Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles, a congregation led by Pastor Solly Drake.

As a .192 hitter on team that lost 120 games, we could probably get away with calling Sammy Drake an unremarkable Met. But it would be inappropriate to say anybody who persevered as he — or Willie Mays or Charlie Neal or George Altman or Choo Choo Coleman — did to make the majors when talent alone wasn’t nearly enough of an entrance fee was anything but a rather remarkable human being.

Image courtesy of New York Baseball History Examiner. Thanks to Crane Pool Forum for helping to gather the names of the ballplayers in question.

Please join us tonight at the first AMAZIN’ TUESDAY of 2010, 7 PM, at Two Boots Tavern on the Lower East Side, as we read aloud, rally around and try to raise a few bucks for the Tug McGraw Foundation. Details here.

Way OT, but too good not to share:

JOSE’S BACK!

I look forward to it being a topic when something actually happens besides a tease.

[…] — quite different legendary times — who hit the road in April was catcher Choo Choo Coleman, Negro League veteran and one of the avatars of the absurdity of the ‘62 Mets. Coleman kept catching even when […]