This isn’t a piece on the Mets and Bernie Madoff, but as explained somewhere below, it was inspired by the current mishegas surrounding those unfortunately linked bedfellows. There is no literal tie between the 2011 mess and what it brought to mind — it’s just that something occurred to me in the wake of what’s been going on and I decided to write about it.

That established, we return now to the pre-apocalyptic final days of Spring Training 1991. The Mets had just completed a string of seven consecutive winning seasons. Thing is, they didn’t know they’d completed it. None of us necessarily did. Our team had averaged 95 wins per annum from 1984 through 1990. We were conditioned by perennial success to believe a similar total would pile up next to the Mets’ name in the standings in ’91, then ’92 and then indefinitely. Winning many more baseball games than they lost is simply what the New York Mets did every year.

If visible storm clouds weren’t yet gathering over Port St. Lucie, one’s Met radar might have detected a change in the weather was in the offing. This, remember, was the spring that followed the winter in which Darryl Strawberry made good on his recurring threats to leave New York for Los Angeles. Right there, 37 home runs and 108 runs batted in boarded a westbound 747. In exchange, essentially, came a theoretical boatload of stolen bases from one Vincent Maurice Coleman and the recently not altogether powerless bat of old friend Hubie Brooks. In modern terms, the 6.5 WAR posted by Straw in 1990 would be replaced by Coleman’s and Brooks’s combined 4.2 WAR.

I’m no sabermetrician, but two guys who were brought in to replace one guy and accounting for two fewer Wins Above Replacement doesn’t seem to add up.

It was a creative solution to the Strawberry void, all right, but that’s not the one Mets executive VP Al Harazin later gave himself a case of the back-pats over. Darryl Strawberry was gone. Replacing him with Vince Coleman and Hubie Brooks would prove a fool’s errand (combined 1991 WAR: 1.3, never mind Coleman’s winning personality), but that wasn’t yet known — even if it could have been predicted had we not developed Met myopia from staring hard at those 95 or so wins every season.

Replacing Dwight Gooden, on the other hand…

What’s that? Replace Dwight Gooden? Unthinkable!

Even with Frank Viola, David Cone, Sid Fernandez and Ron Darling returning from 1990’s 91-71 squad, the Mets wouldn’t have been the Mets without Doc…not even without the Doc who was no longer automatically threatening to go 24-4 in a given year. In 1990 — when a panel of leading National League hitters, convened by the Sporting News, named him after all those years the senior circuit’s toughest pitcher — Gooden’s won-lost record was 19-7, highlighted by a vintage 16-1 stretch that spanned the Mets’ surge into their seventh pennant race in seven seasons. Gooden received a ton of run support in ’90 (6 runs every 9 innings), but Doc returned the support when it mattered most intensely in September.

Four of the Mets’ ten best starting pitcher Game Scores in their final month of ultraserious pennant contention (until 1998, as it turned out) were achieved by Gooden. The Mets went 5-1 in Gooden’s September 1990 starts; the only loss occurred when they handed a 3-3 ninth-inning tie to John Franco and Franco a) couldn’t keep Tim Raines at first base (stole second, wild pitched to third) and b) couldn’t retire the immortal Junior Noboa (go-ahead single that, per usual, found a hole between infielders). When Gooden wasn’t starting that September, the Mets’ record was 10-14. They finished four behind the Pirates in 1990.

There was a security blanket aspect to Dwight Gooden pitching every fifth day, even when he wasn’t operating like the Doctor of his slowly receding youth. Doc would be 26 when the 1991 season began. It was young for most pitchers. It seemed young enough for Gooden, though by now he was an old fixture, someone on whom we had come to rely for his presence as much as his stuff.

But what if we were to go without any of it? Not for two sad months of Smithers Institute rehab as was the case in 1987 nor for a couple more months due to an aching shoulder in 1989, but for good? It was unthinkable, but the possibility loomed as St. Lucie filled up in February 1991. Dwight Gooden was entering his walk year. He had been a well-paid 24- and 25-year-old pitcher and would be handsomely compensated again, at 26. Prior to the 1989 season, Doc signed a then industry-leading deal that would earn him $6.7 million across the next three seasons, 1991 being the last of them. But this was baseball, where superstar salaries were (and are) always climbing upward. In the winter of 1991, Doc — staff ace for a team that had never not contended with him as its top gun — was due for a big raise.

The Mets avoided giving one to Darryl Strawberry in 1990, his walk year. Every night, after Darryl would launch a barrage against one National League scoreboard or another, Howie Rose would come on Mets Extra and offer his counsel to GM Frank Cashen: “Pay the man!” Cashen didn’t listen. The Dodgers did. It wasn’t a popular decision in New York. But, you could reason, that was Darryl, and Darryl was…you know, Darryl.

This was Dwight…Doc. You can’t lose Doc. You can’t even think about losing Doc.

But can you pay him what he wants? You can’t say Doc hadn’t earned a surgeon’s ransom: 119-46, 2.82 ERA, 8.2 strikeouts for every 9 innings pitched since 1984. Who had been better? More dominant? More consistent?

There was only one other pitcher in the conversation in the spring of 1991, and he was, if you’ll excuse the expression, Roger Clemens. Clemens crossed paths with the Mets memorably in the 1986 World Series and would present himself and his huge ass (Shawn Estes notwithstanding) again on a recurring basis between 1997 and 2007, but his role in 1991 was of an off-stage nature…off-stage and upstage, you might say.

Clemens got the contract he (grrr…) deserved that February, four years, a little more than $21.5 million, or $5.38 million annually. That was the kind of number on which Cashen choked the previous summer when it was suggested Strawberry had an enormous payday coming. Nevertheless, Gooden wanted to reside in Mr. Roger’s neighborhood.

The Mets were not rolling out the Welcome Wagon, as such.

Four years was one year too long by their calendar — a “dealbuster,” by Cashen’s reckoning. Thing is, Gooden not only wanted a Clemens-like deal but wanted it in place by the time pitchers and catchers reported (February 22, in 1991). As that Doc-imposed deadline approached, the Mets’ offer was three years for $13 million, or $4.33 million a year through 1994. When the deadline slid by like Vince Coleman under a shortstop’s tag in his Cardinal days, talks were broken off. Gooden made no secret of his miffedness when he told a press conference, “The next time I talk to the Mets, I’ll be talking to everybody. We’ll see what everybody feels about Dwight Gooden.”

Dwight Gooden was the Mets’ best pitcher entering 1991. He was the Mets’ best player. Next to Tom Seaver, he was the most important player they’d ever had, and it wasn’t heresy after seven seasons to suggest that by the time Gooden’s career was over, he might earn equivalency with Seaver in Franchise status. Tom, Doc…Doc, Tom…the historical race was too close to be called at that juncture.

Never mind experiencing another Darryl Strawberry-style exit. Imagine a replay of June 15, 1977. It was unimaginable to the Mets fan as winter became spring in 1991, yet here was The Franchise, Jr., suggesting he was being pushed out the door.

To think it, no matter what we know with twenty years’ hindsight, is to shudder at it.

Thankfully, in negotiations, absolute deadlines suddenly prove movable, just as hard and fast numbers tend to shift with the breeze. The Mets and Doc’s agent, Jim Neader, returned to the bargaining table and kept talking after pitchers and catchers arrived at camp; after position players joined them for full-squad workouts; after exhibition games began; after — as happens every spring — the whole March baseball panorama lost its novelty and everybody got antsy for the season to start already.

With one week remaining before Buddy Harrelson would hand Dwight Gooden the ball for his sixth Opening Day start, it got done. Doc had a new contract, effective with the expiration of his current pact. It wasn’t what Clemens got, but it more or less satisfied Team Doc.

“The bottom line is we got what we wanted,” agent Neader said. “The Mets got Dwight for three years and Dwight got his $5.4 million,” referring to his average annual compensation if you took all incentives, bonuses and other factors into account. Added up that way, it topped Clemens’ yearly number, making Doc the highest-paid player in the game. Calculated by base salary, Clemens held the edge by about $230,000 per year, a relatively minute amount in the world of baseball megabucks, even back then. Being No. 1 was “important,” Gooden said, “but when it’s that close, it doesn’t really matter.”

It must have mattered to the Mets, because it was that close, and they stopped just short of it and couldn’t bring themselves to simply pay The Man. “If we step up and make the Clemens standard the standard of the Mets,” Harazin said when negotiations took a sour turn in February, “it impacts on the entire organization. Everything flows from that.” Viola was entering his walk year, too, that spring, so the Mets had a multitiered interest in keeping the price of pitching down.

“To them, it’s a business,” Gooden reasoned in early April as regarded his not insignificant $5.15 million average annual base salary, “and so you can’t blame them for having tried to get me as cheap as possible.” Harazin, meanwhile, spun it as a win-win: “The beauty of the deal is that it can be perceived in different ways by different people. We’d like to think we stood up for things we believed in.”

Harazin labeled it a “unique contract for a unique player,” partly to signal to Frank Viola that, comparatively speaking, he wasn’t nearly as special to the Mets (Gooden was the “heart and soul of the club,” according to Cashen’s ranking deputy) and partly to take a bow for devising a clever-seeming contractual provision. Anybody could pay a pitcher millions of dollars. Anybody could lay out a signing bonus. Anybody could promise more money based on innings pitched. And Doc definitely had all of that coming if everything went to plan.

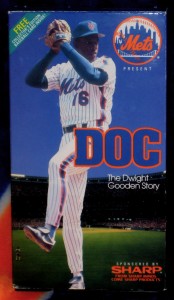

But only the Mets, it seemed, could come up with a clause paying Dwight Gooden $250,000 a year for three years for, as the New York Times put it, “the right to produce and use Gooden in commercial videos.” The Times’ Joe Sexton reported it was the video idea, proposed by the Mets late in negotiations, that “clinched the deal”.

So Clemens’ package was “irresponsible and incomprehensible,” in Harazin’s words, but guaranteeing Gooden three-quarters of a million dollars by saying it was for videos and not pitching…well, Al was right. It was unique.

Videos? What the hell did that mean? It certainly brought out the wiseacres in the New York press (proving, perhaps, that bloggers didn’t invent snark). George Vecsey of the Times wanted to know, “Will he carry a synthesizer with him on the road to work on some rap music?” Tom Verducci, then with Newsday, suggested, “The organization can build an entire Mets library of videotapes while thinking they are holding down salaries.” Verducci’s gems included:

• Duck Hunting with Kevin McReynolds

• Surfing with Sid

• Jeff Innis, Live at the Improv

As for what that element of the contract actually yielded, there was one video produced, titled, Doc: The Dwight Gooden Story. It was filmed (taped, actually) during the 1991 season and — perhaps ominously — had its world-premiere screening that November, when Harazin, since promoted to succeed Cashen as GM, was preoccupied by free agent negotiations with Bobby Bonilla and Eddie Murray.

They’d be wanting money, not videos, but at the public screening for Doc, Harazin did not indicate any displeasure with the final product the previous spring’s dickerings brought about. “It solved a variety of objectives,” Harazin told the Times. “Desperation breeds creativity.”

I don’t recall the Mets advertising Doc quite that way, but as soon as they put the word out that the first (and only) Dwight Gooden video was available, I raced to my nearest Nobody beats the Wiz and purchased a VHS copy. I watched it immediately, stored it on a shelf, took it down a couple more times in the ensuing two decades to either cheer or depress myself during dark Met times and otherwise hadn’t given it any thought until just the other week. Those recent revelations about the unholy link between the clever deferred payments to Bobby Bonilla and how the money for them was supposed to be bearing interest in Bernie Madoff’s accounts, however, served for whatever reason to remind me of Al Harazin’s 1991 creativity — even if nobody has cause to sue anybody over Doc: The Dwight Gooden Story.

I’ve no reason to believe this video isn’t a perfectly legal 50 minutes of baseball entertainment.

However it came about, I found myself thinking about it lately, so I took the tape down from its shelf once more and watched Doc: The Dwight Gooden Story for the first time in who knows how long. I can report it remains alternately cheerful and depressing, depending on your Met mood.

Doc is clearly a curio from its time, both for production values and content. Anybody who’s excessively watched An Amazin’ Era or A Year to Remember will recognize it as emanating from the same basic school of Met video storytelling, save for the lack of a recognizable soundtrack. Amazin’, which commemorated the 25th anniversary of the Mets franchise, and Remember, the tribute to our second world championship, were both made in 1986, when MTV’s influence was cresting. Thus, “real” music was a must, whether you were setting highlights to Petula Clark and Neil Diamond (An Amazin’ Era) or Duran Duran and Bob Seger (A Year to Remember).

By 1991, the Mets weren’t paying the necessary rights fees to use anything you’d ever heard, though an original hip hop theme, “Doctor Doctor” was composed for the occasion — credited to Richard Fiocca and D.C. Smooth. Though it focuses on Gooden and his ability to throw strikes, “Doctor Doctor” is not to be confused with Mellow Mel’s 1986 recording, “Dr. K,” nor, for that matter, Robert Palmer’s 1979 hit, “Bad Case of Loving You (Doctor, Doctor)”.

Nothing about Dwight Gooden’s synthesizer was mentioned in the credits, but crafting scores for video productions was about the only thing Doc couldn’t do if you believed Doc. And why wouldn’t we? Who was going to buy this thing except Mets fans for whom Dwight Gooden indeed represented heart and soul, even at the late date of winter 1991-1992?

Doc, it should be noted, wasn’t a warts-free exercise in hagiography. There was always an elephant-sized drug test in the room when the subject was Gooden’s career and it was impossible to avoid. The video therefore dealt honestly with his 1987 brush with cocaine even if it couldn’t offer foolproof prophecy regarding relapse. Aside from that detail, and a little problem regarding arthroscopic surgery curtailing his most recent season — and, oh yeah, an ill-fated pitch to Mike Scioscia in October 1988 — it was all good.

“All good” always carries caveats when you’re a Mets fan.

The narrative is otherwise what you’d expect. It’s all about greatness. Doc was a great kid growing up in Tampa. Doc had great parents. Doc was, of course, a great rookie in 1984 and authored an all-time great season in 1985. Doc was a great Met among Met greats in 1986, the greatest season of them all. Doc has great career numbers. Doc’s a great teammate. Doc’s a great practical joker. Doc’s a great hitter (within reason). Doc’s a great guy to be around. Doc’s got great character. And once his shoulder is completely healed, goes Gary Cohen’s’ voiceover, “He’ll be here at Shea creating more memorable moments.”

Two ghosts hover over Doc — his and the Mets’ past, and his and the Mets’ future. Despite insisting that in terms of technique, “I’m a better pitcher now than in ’85,” we know his best days came when he was 20 years old. We intellectually understood that when this video came out, but we still held out hope that the Doc Gooden of 1985 (24-4; 1.53 ERA; 268 K’s in 276.2 IP) might peek his head in now and again in 1992 and thereafter. After Dwight went 13-7 (3.60 ERA; 150 K’s in 190 IP) in his injury-abbreviated 1991 campaign, it didn’t seem altogether out of the question.

But 1985 was long over by then, just as 1986 was. Doc: The Dwight Gooden Story was released by a company called Halcyon Days, and clearly the Mets’ halcyon days were fading by the early ’90s. While Doc footage was being recorded, the 1991 season — projected as the Mets’ eighth consecutive year of contending — unraveled like a cheap Fan Appreciation Day scarf. It’s no wonder, then, that references to ’86 feel like allusions to another time entirely. By late 1991, the 1986 Mets were of an era separate from the present. Except that Dwight Gooden and a handful of teammates were still on the roster, the 1986 Mets might as well have been the 1969 Mets, and that’s how they are treated in Doc: as distant, sepia-toned nostalgia.

Sigh.

As for what lay beyond 1991, it couldn’t help but spread out as “who knows?” territory, but you watch Doc, and you wish you could delete the parts all but promising for Gooden more World Series appearances, 300 wins and an inevitable landing spot in Cooperstown. There’s a moment when pitching coach Mel Stottlemyre is telling Doc, “The next time you’re out there in a playoff situation or World Series situation, somebody’s gonna pay.”

At that point, Mel is smacked in the face with a pie, which, in retrospect, is what happened to all of us where Doc and the Mets after 1991 were concerned.

Who could know, exactly? Who could know that Doc Gooden, like the Mets, would not post a winning record in 1992 or 1993, or that in 1994 he’d throw his last Met pitches (dreadful ones, mostly) on June 24. Who could have conceived he’d fall short of pitching 500 innings over the life of his three-year contract and not collect what was surely supposed to be one of his gimme bonuses? Who wanted to consider that the segment about cocaine and 1987 wasn’t a cautionary tale but a prequel?

If you dare to watch Doc, you have to glean from it the enjoyment you would from any random time capsule you come across. You have to enjoy Dwight’s fade haircut. You have to respect his wearing surgical scrubs and a Janet Jackson Rhythm Nation t-shirt while paying a goodwill visit to a hospital. You have to marvel that somebody thought to interview Gary Carter while he was a Dodger, Tim Teufel while he was a Padre and Dale Murphy while he was a Phillie. You have to remember when you see Mark Carreon and Mackey Sasser representing the 1991 Mets with “Gee, Doc is swell” testimonials that maybe it wasn’t so shocking the Mets were about to decline precipitously as a competitive entity.

With hindsight, we can see 1991 was this franchise’s sign of the apocalypse. They were so generally good in the years before it; they were so very bad in the years after. The Mets slipped from 91-71 in 1990 to 77-84 in 1991. Heart and soul notwithstanding, the Mets were less and less Dwight Gooden and more and more Sasser and Carreon, Coleman and Brooks, whoever and whoever, none of whom could ward off the impending storm of ineptitude that was about to drown Metsopotamia. 1992 brought a new-umbrella brigade to Flushing — Jeff Torborg in for Buddy Harrelson; Bobby Bonilla in (in essence) for Darryl Strawberry; Bret Saberhagen in for Frank Viola — but that didn’t provide protection, either, and the spiritual flood commenced.

I don’t know how many Mets fans need guidance on how best to watch Doc: The Dwight Gooden Story since I doubt there are many copies in circulation. It was offered in a doomed format that as far as I know never found new life in DVD or Blu-Ray, and YouTube yields no indication that any Mets fan ever transferred it to digital or dared attempt to sneak it by MLB’s watchful eye. Even in real time, during the twilight of the Doc, I don’t think it was what you’d call a hit. In the spring of 1994, more than two years after its release, I visited the Mets Clubhouse Shop in Roosevelt Field in search of a road batting practicing jersey that had caught my eye.

“We don’t have it,” I was told by a clerk who pointed to a rather dense display of blue VHS boxes. “But we have a ton of Doc the video.”

More recent Mets-related video release, available here, highly recommended.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by You Gotta Believe!, Greg Prince. Greg Prince said: Revisit "Doc: The Dwight Gooden Story, a VHS born of a #Mets' front-office creative impulse from 1991 haggling. http://wp.me/pKvXu-22G […]

Hi Greg,

Your writing got me to think of the sad way the life of the subjects in both of those videos, Doc Gooden and Billy Joel, parallel each other. Both found success during the height of the drug culture and in turn became victim to it. The difference is that Doc appeared as a down to earth kid while the other was arrogant and self-centered, thus the young pitcher’s problems came as a shock while, at least to me, those of the piano man didn’t.

But still, sad examples of what can happen when fame and success comes so quickly at such a young age. though the same can happen to ones equally as young but without celebrity and wealth as well.

It was during the heady days of summer 2006 that I came across a like-new VHS tape of “DOC: The Dwight Gooden Story”. It lay among some used toys and old sneakers on a faded blanket, on someone’s suburban lawn during yard sale season. For fifty cents American currency, it found its way into this Met fan’s library.

Similar to Harry Chapin’s Taxi Driver, I stashed the tape in my car trunk, like Chapin’s driver stashed the $20 bill in his shirt: with a touch of nostalgia, a whiff of regret and acceptance of a failed love affair.