The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 9 July 2024 8:37 am The following is an excerpt from an article slated to be published in a forthcoming edition of The Metropolitan Journal of Sports Medicine, detailing critical work in the field of preservation of pitchers’ health.

The veritable plague of pitching-related injuries and subsequent Tommy John surgeries encountered a most serious challenge as the result of advances put forth in the summer of 2024 by a combined team of Drs. Stearns, Mendoza and Hefner when they prevented their patient, who we shall refer to as Christian S., from throwing more than 77 pitches in a given baseball game. The “organization,” as the consortium of doctors labeled themselves, determined in advance of Christian S.’s forthcoming outing that he would be removed from his starting assignment at roughly 75 pitches, no matter how well he was doing. Pitchers prior to this start routinely approached 100 pitches, indicating a pitcher pitching well could be left to proceed as if nothing was wrong with him.

As it happened, Christian S. was doing very well, having pitched five-and-two-thirds innings and giving up only one hit, a two-run home run to Oneil C., and walking only one opponent. Christian S. appeared vital enough to continue pitching without restriction and face at least one more batter, the dangerous Bryan R., an All-Star performer Christian S. had retired twice previously in the same contest. A similar outcome would have required only a handful of additional pitches from Christian S. to complete six full innings and position the organization for immediate success.

This is where the breakthrough work of Drs. Stearns, Mendoza and Hefner came into play. Adhering to their notion that approximately 75 pitches should be all Christian S. — then 25 years old and showing no physical ailments — be allowed to throw, Christian S. was removed in favor of Eric O., a then unknown reliever being asked to make his first appearance at the highest level of his profession in a tie game at the end of a road trip that would be described either as “winning” or “.500,” depending on the outcome of the game in progress.

In the short term, the decision to remove Christian S. in favor of Eric O. proved deleterious to the competitive health of the organization, as Eric O. (who did not pitch altogether badly) failed to set down any of the required three batters he faced and allowed the even score he inherited to become a deficit. Eric O. gave way to Adrian H., and things got inalterably worse from there.

While pitching machinations are the focus of our study, it should be noted that the organization’s offensive interests weren’t served by any member other than Brandon N., as none of Brandon N.’s colleagues found a way to counter the strengths of familiar organizational impediment Mitch K. (see “Finger of Starling M. and Fate,” September 2022). All of this is to say that the game was lost in multiple fashions.

While an 8-2 defeat and a dispiriting end to a road trip amid a highly charged playoff-berth pursuit dominated the thoughts of those who were invested in the fortunes of the organization in the summer of 2024, the long-term effects of the removal of Christian S. potentially proved beneficial, as throwing only 77 pitches, when to all observers he had the capability to throw a few more, conceivably guaranteed not only continued health for Christian S. but might have provided a road map for all young pitchers forever more.

“It turned out it was just that simple,” according to a statement issued under the names of Drs. Stearns, Mendoza and Hefner. “We pick a specific number of pitches; the pitcher is not permitted to exceed it by much regardless of game situation; and then everything is fine. Clearly it’s as easy as all that, because we’re pretty sure nobody had ever thought to put a young pitcher on a pitch count before. If they had, none of them would have been subject to injury, right?”

by Jason Fry on 7 July 2024 11:05 pm When your team’s going well, you call a game like Sunday afternoon’s things like “an inspiring win” or perhaps “proof of resilience.”

When your team’s going badly, you just laugh at being randomly atop karma’s wheel for a day.

I’m not sure what to call Sunday afternoon’s game, because I’m not sure what the Mets are.

One of the joys of baseball — which was a lot more joyous before they stuck a football-style clock on the proceedings — is the way good games unfold with a surface lack of action that hides the tension being ratcheted higher and higher, until boom! that tension is released in a hurry and anyone who’s been paying attention realizes that was the payoff of all the apparent quiet.

So it was Sunday, when Sean Manaea and Luis Ortiz traded zeroes for six innings and then handed it over to their bullpens. Both teams emerged from the seventh unscathed, but the eighth was another story: Things were about to happen in a hurry. In the Mets’ half, All-Star snub Brandon Nimmo laced a double off former teammate Colin Holderman to chase home Francisco Lindor and give the Mets a 1-0 lead. In the Pirates’ half, Dedniel Nunez was removed after getting two outs (and allowing two hits) in favor of Edwin Diaz. Diaz? With four outs to get? After working the night before? (Admittedly, with relatively few pitches thrown.) Without a clean slate?

Cue mutterings from the large contingent of visiting Mets fans at PNC Park and all of us on our couches farther away. And, indeed, Diaz walked Joshua Palacios on four pitches and his fifth pitch was a slider that sat in the middle of the plate, and which Nick Gonzales spanked into center for a two-run single and a Pirates lead. That sent the Mets out for the ninth a run in arrears with Aroldis Chapman — he of the fastest reasonably documented pitch ever thrown — filling in as the Pittsburgh closer.

Chapman got two quick strikes on Francisco Alvarez, but this year Alvarez has developed an ability to fight his way back into counts that brings to mind Edgardo Alfonzo and a young David Wright, as well as current specialist Nimmo. Alvarez worked the count to 3-2, spat on a slider that was just low, and was replaced at first by Ben Gamel. Harrison Bader fought his way to 3-2 and singled, putting speed on the bases and bringing up Mark Vientos.

Hope? It’s a delicate thing — a little bird to hold gently on your palm while it dries its wings, perhaps assisted by some gentle exhalations to speed the drying process up and accompanying assurances that the sky is wonderful and little feathered friends will love it up there. Vientos went down 0-2 on a pair of sliders, worked the count full … and got caught looking at a slider when he was expecting a fastball.

One out, ugh — and the ughs were compounded when Luis Torrens went down on three straight pitches, having clearly been looking for the exact opposite pitch of what Chapman had given him three times in a row.

Jose Iglesias was up as the Mets’ last hope, and I allowed myself to think he was exactly the kind of hitter I’d want there — possessed of a good eye and a reputation as a battler. And Iglesias did battle, fouling away putaway pitches at 101 and 102 before walking on a 101 MPH four-seamer a hair below the zone.

Chapman’s pitch count was rising steadily, and here came Lindor — who can look hopeless at the plate in one AB and like a wizard in the next one. Chapman’s third pitch was a slider that got too much plate; Lindor squared it up and a moment later it was touching the outfield grass and the Mets had the lead back.

Hope was flapping happily around at treetop level tweeting that the world was a wonderful place, but I was holding my breath because I knew what it didn’t: there are hunters lurking in the sky that a little bird doesn’t want to meet. Diaz went back out to the mound after nearly half an hour of sitting and, one feared, marinating in his own unhappiness about what had transpired. His first pitches to Oneil Cruz weren’t exactly reassuring, either: sliders getting too much plate and fastballs missing a bit of crucial juice.

But Diaz got Cruz looking on a slider at the knees and his pitches then seemed a lot crisper against Rowdy Tellez. He grounded out and Diaz went to work on Jack Suwinski, who worked a full count but tapped a ball harmlessly to Iglesias. It nestled in Pete Alonso‘s glove and the Mets had … enjoyed the rotation of the karmic wheel? Yanked one out through pluck and grit?

Damned if I know — every time I think I do, the Mets try and convince me of the opposite. What I do know is they won, and they’re about the most interesting .500 team one can imagine, even if you have no idea where that’s taking them.

by Jason Fry on 6 July 2024 11:57 pm In the early going Saturday, it sure looked like the Mets had reverted to the unholy mess they were throughout May. In the first inning they followed second and third and nobody out with a pop-out and a pair of Ks; in the second they wasted a leadoff single and then a one-out double. In the third, they loaded the bases with nobody out against Bailey Falter, who threw ball one to Pete Alonso and then departed with arm discomfort.

On came old friend Dennis Santana, whom you may have forgotten was a Met for nine games last year. Santana, throwing nearly all sliders, went to 3 and 2 on Alonso and I exhorted the Polar Bear not to swing at a bait slider.

The Polar Bear swung at a bait slider.

Up came Mark Vientos, who didn’t see a single pitch in the strike zone and struck out. (To be fair to Vientos, Santana’s slider was a lot sharper by now.)

The Mets were doing it again, weren’t they? Enter Luis Torrens, who wound up pitching in Friday night’s debacle, when he was the most effective hurler the Mets had to offer.

Santana threw a bait slider, which Torrens ignored in a sign of Metsian progress. Then Santana left a slider in the middle of the plate and Torrens didn’t miss it. He drove it into that funny nook in PNC Park’s center field, the only place where that distance wouldn’t yield a grand slam. It was a three-run double instead. “Finally!” said Gary Cohen, speaking for us all.

The game trundled along from there, with Oneil Cruz hitting a two-run homer into the river that glanced off the foul pole and might possibly have gone through it, leaving one of those cartoon bore holes, and Jose Butto relieving David Peterson in the fifth, which meant more rounds of reliever roulette.

The break point came in the seventh, when Reed Garrett struggled with his control, loading the bases with one out. He got a lineout from Ke’Bryan Hayes and then faced Jack Suwinski as a pinch-hitter.

It gives me no joy to say that Suwinski had to overcome not only Garrett but also home-plate umpire John Tumpane, who lost the strike zone in sync with Garrett. Garrett threw a sinker below the strike zone on 1-0; Tumpane called it a strike. On 3-1, Garrett missed low again; Tumpane called that sinker a strike as well. As Suwinski blinked in disbelief, Pirates skipper Derek Shelton emerged from the dugout red-faced with rage and was quickly tossed. On the next pitch, Garrett struck out Suwinski to end the inning.

It went our way, but it was nonsense. And this kind of nonsense swings games all the time — the Suwinski AB was glaring because of the game situation, but look carefully and every night you’ll see see 2-1 counts transmuted into 1-2 counts and vice versa because umpires miss pitches. Those blown calls tip the balance between hitters and pitchers and change outcomes — just not under the same spotlight as bases loaded, two out and a game on the line.

I’m all for the human element in baseball. But the human element should be a pitcher trying to dot the outside corner or a hitter outguessing the pitcher and zoning in on his pitch. It shouldn’t be a referee failing to do his job and so distorting the proceedings. Robot umps now!

Anyway, with Garrett having gotten an assist past Suwinski the game wound up in the officially ruled not inappropriately sticky hands of Edwin Diaz, returned from his 10-game suspension. Diaz started off by hitting Cruz, then drew a pitch-clock violation, and that sound was thousands of Met-fan heads going into Met-fan hands.

But then Diaz found it in a hurry. He struck out Pittsburgh folk hero Rowdy Tellez and got a grounder to short from Andrew McCutchen that became a game-ending double play. Seven pitches after we were all like, “Oh God not this again” the ballgame was over and the Mets had won — won on a day when everything kept looking like it was about to become unbearable but somehow, to our infinite relief, did not.

by Greg Prince on 6 July 2024 11:54 am Congratulations to the New York Mets of July 5, 2024, for doing something no Mets team had ever done before in a blowout loss so bad that a position player had to pitch. On Friday night, the Mets, whose last call to the visitors’ bullpen at PNC Park would summon catcher Luis Torrens, actually stayed close until fairly late. They trailed only 4-2 as the black & gold-clad crowd rose for the seventh-inning stretch, giving every indication they were very much in a game they had led as recently as the top of the fourth and were tied as recently as the top of the fifth.

Losses so resounding that they result in a Plawecki, a Recker or a Torrens staring in at somebody crouching where they usually find themselves tend not to be backloaded in their defining momentum. In the twenty previous episodes of You’re Not Gonna Believe Who’s Pitching, including the affair of August 15, 2021, when Mets fans resorted to that line twice (the night Kevin Pillar had to relieve Brandon Drury), the Mets were pretty well out of the game before everybody was in their seats, though there were a few first-inning Met leads that melted quickly, starting with the progenitor of all such improv embarrassments, Mets at Pirates, September 26, 1992. That Saturday afternoon, New York jumped ahead via the kind of attack that, if you knew nothing else except the game right in front of you, validated the signing of Vince Coleman two winters prior. Vince singled on a three-two pitch from Bob Walk to lead off the festivities; stole second while Walk worked to Chico Walker; cooled his heels while Walker worked a walk off Walk; and came home on Daryl Boston’s single to left. The Buccos were on the verge of clinching their third consecutive NL East title and the Mets were playing out as disappointing a string as they had ever unfurled, but in the moment, Jeff Torborg’s team was playing smart, heads-up baseball, running the opposition ragged.

The moment ended when the Pirates came to bat in the bottom of the first. They scored six runs. Four were on a grand slam belted by ex-Met farmhand Lloyd McClendon. Two were doubled in by Walk, who shook off the top of the inning pretty easily. Then came six more runs in the bottom of the second, featuring the final home run bopped by Barry Bonds in a Pirate home uniform. Then, in the bottom of the eighth, Met infielder Bill Pecota scaled the mound. He wasn’t there to pep-talk his pitcher. He was there to be the pitcher, the first time a Met position player had ever assumed that responsibility. The first Pittsburgh batter, Andy Van Slyke, homered to change the score from 18-2 to 19-2. Pecota held the line from there.

That’s usually how these position player/pitcher games go. By the time the manager gets super desperate, the game’s been a foregone conclusion for ages. Take the three games in this category started by Steven Matz…please. Matz could do some fine pitching in his Met day, but he also had a tendency to implode. Once in 2018 and twice in 2020 (a season that had only sixty games total), Matz took the hill only to have the Mets running for them. They were down to the Nats, 7-0, in the first on July 31, 2018; down to the Nats again, 5-0, in the third on August 10, 2020; and down to the Braves, 5-0 in the second on September 18, 2020. The respective finals in those Met losses were 25-4, 16-4 and 15-2. The respective closers for the Mets? Jose Reyes, Luis Guillorme and Todd Frazier.

Met annals are punctuated with these oddities that unfortunately aren’t as infrequent as they used to be (none between 1962 and Pecota; thirteen since 2017). Friday night’s incident may have been the oddest of them all in that it did not appear to be a candidate for cataloguing under Blowout That Blowed Up Real Bad. The Mets hit the ball hard a bit versus rookie phenom Paul Skenes when Skenes — 7 IP, 8 SO — wasn’t throwing the ball past them quite a bit more. Jeff McNeil homered in the third. Pete Alonso doubled with authority to lead off the fourth and came around to register the second Met run. Even after Luis Severino gave up a pair of solo shots in the bottom of the fourth, the Mets were level with their hosts. For a decent spell after Bryan Reynolds parked another Sevy serving with a man on in the fifth, the game stayed within reach. Down 4-2 going to the bottom of the seventh is hardly a death sentence.

The next sound you heard was the Mets walking the plank. First Severino tumbled into the drink with nothing left: double; single; walk; exit. Next, for reasons best known to Divine Providence, Jake Diekman, the lefty who has still not taken our well-intentioned advice to fling his glove into the stands in order to inspire a designation for assignment à la Jorge Lopez (the Mets could hold a team meeting afterward as well). Nope, Diekman, the old pro, conducted himself with utmost comportment after surrendering a grand slam to Reynolds, putting the game that had been within the Mets’ grasp all night completely beyond the longest of their fingertips.

Because the rules say the Mets must suffer the consequences of their mysterious decisions, Jake had to hang around for two more batters. He gave up a single and a walk, or the least damage one imagines Diekman can do. The veteran gave way to a less-heralded journeyman type, Ty Adcock, who slithered out of his inherited jam thanks primarily to Oneil Cruz necessitating an interference-tinged double play by running directly at third baseman Jose Iglesias while Iglesias was in the act of fielding a ground ball. Thank heavens for dim favors.

Adcock would get his chance to know the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela in the bottom of the eighth, as three different Pirates sent three of Ty’s pitches toward the mighty Ohio. Three homers for Three Rivers, thrusting Pittsburgh ahead, 14-2, or ten runs better than it was barely an inning before. The last of the dingers, bashed by Rowdy Tellez, was the Bucs’ second grand slam of the game, not to mention the seventh of their franchise record-tying home runs. Worse, somehow, was that amid all the cannon blasts (PNC literally ran out of fireworks), Adcock couldn’t mix in a third out.

Ergo, Torrens, who got his man (0.1 IP, 1 BF, 0 R). If you’re looking for a Rolaids Fireman of the Game candidate on the Met side, you could do worse than the backup catcher. You couldn’t possibly do any better.

Oh, and welcome back, Edwin Diaz. Wash your hands, clean your glove and start getting warm.

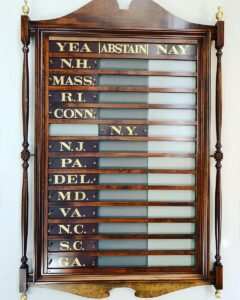

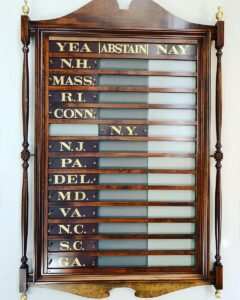

by Greg Prince on 4 July 2024 6:38 pm I loved watching the great victory today, a shutout for our side, with New York coming through toward the end. I am referring, of course, to my annual viewing of 1776, a film I still find worth watching every Fourth of July, my custom since 1991 and something I hope to do as long as the American Experiment continues to produce net-positive results.

Some late-inning Fourth of July box scores are more promising than others. Before the movie, I watched New York not come through toward the end nor at any point of the proceedings, resulting not in a suspenseful 13-0 blowout for the forces of independence, but in a 1-0 drubbing in Washington, a town where good things have been known to intermingle with the other kind. The best part of this particular blanking was it was over with early, a function of the game staring at 11:05 AM. My pregaming, as it were, consisted of a nap. Continuing it rather than disrupting it so I wouldn’t miss too many pitches likely would have been more satisfying.

The game in a nutshell: it’s nothing-nothing at the outset of the bottom of the eighth. I wander into the kitchen, half-listening to the TV audio from the living room. I hear Gary Cohen identify a Nationals batter as someone who has hit five career home runs off Adrian Houser. I do a quick calculation and assume he’s talking about ex-Red Jesse Winker, since who else on the Nats would have faced ex-Brewer Houser often enough to hit five home runs off him?

A moment later, I’m watching Winker Dinger No. 6 fly over a fence. I not only saw it, but I saw it coming…as, I imagine, did every Mets fan who processed the foreshadowing.

Kudos to Jose Quintana for preventing more than a bullpen cameo. Seven shutout innings ain’t nothing in the land of double-negatives. Thanks to Jeff McNeil for assuring we wouldn’t be no-hit, though some days it doesn’t feel as if avoiding highlight infamy matters. When you’re not hitting, being one-hit is only one hit better than being no-hit — y’know? Jake Irvin quelled every non-McNeil Met completely for eight innings and Derek Law took care of the rest. There’s something about a 1-0 Met loss put in the wrong side of the books in under two hours that’s as American as apple pie. It’s part of summer the way you remember it from when you were a kid, kind of like getting bitten by a mosquito.

by Greg Prince on 4 July 2024 9:19 am I gotta tell ya, I was really rooting for Jake Diekman on Wednesday night. More than I was behind Tyrone Taylor when he confounded the left field foul pole for his home run to lead off the third; more than I cheered Mark Vientos making the shrubbery beyond the center field fence at Nationals Park his personal meditation garden in the fourth; more than I applauded Francisco Lindor turning the disappointment of Ben Gamel’s near-home run moot by belting a two-run home run of hiw own with Gamel on second in the fifth; more even than I was delighted to have Christian Scott back in the major league rotation, I was all in on Jake Diekman.

“C’mon, Jake,” I urged, “I know you can do it. I have confidence in you. I BELIEVE in you! Go get ’em, Jake!! You’ve got this!!! This is YOUR moment!!!!”

But, alas, Jake didn’t do what I truly wanted him to do. He did not follow the example his former teammate Jorge Lopez set weeks earlier and he did not fling his glove into the stands in disgust after a terrible outing. I so yearned for Diekman to commit an unprofessional act and thereby compel the management of the New York Mets to designate him for assignment on the spot, meaning he’d never come out of the Met bullpen again and throw another inning like he did in the seventh, when he gave up a ten-pitch walk, a double and a single in succession and allowed a slim 5-4 Mets lead to transform into a 6-5 Nationals advantage en route to a 7-5 Mets defeat.

I thought you could do it, Jake. Next time (and it appears there will be a next time), remove your glove from your right hand and aim for the fans behind the dugout. Or, in your case, somewhere near them. Just be as bad coming off the mound as you routinely are on it and give the front office the nudge it needs. I still believe you can do it.

by Jason Fry on 2 July 2024 11:39 pm This recap’s headline is a term we’ve heard a lot in the sabermetric age, as front offices search for previously overlooked and/or undervalued traits in players. The last two nights, I’ve found a new market inefficiency as a fan: You don’t need to watch the part of the game that doesn’t matter.

I don’t recommend this strategy, because a) it’s hard to pull off consistently; and b) the fun of baseball is the journey and not just the destination. But for two nights in a row I have to admit it’s worked.

On Monday night I arrived for duty in the sixth; once I had the Mets drew even, blew the Nationals’ doors off in extra innings, and then survived a harrowing bullpen meltdown to win. (Whoops, sorry, I meant to type “another harrowing bullpen meltdown.”)

Tonight a dinner out in Brunswick kept me away from my station, save for a couple of under-the-table glances at Gameday. (I kept getting caught because Face ID doesn’t work that way.) I saw the Mets were down 1-0 and then down 2-0 — the stuff of resigned sighs back in May, but not quite so worrisome now.

I saw that, but I missed the Mets drawing even on a Francisco Lindor homer and an RBI single from Brandon Nimmo, apparently recovered from the scare he got fainting and gashing his head in a D.C. hotel room, and in the game because of a scare Harrison Bader got crashing into the outfield fence. (Stay tuned.) I figured out those details later; when I turned MLB Audio on for the drive back up the coast all I knew and all I needed to know was it was 2-2.

Which it stayed until the top of the 10th, thanks in large part to Francisco Alvarez gunning down speedy rookie James Wood. That meant the Mets were looking to drive in their Manfred man, suddenly a nightly occurrence in these parts.

(I know you’re expecting the giddy part of the recap, but nope, I’m climbing up on this here soapbox.)

One of the things I dislike about the free runner — besides the fact that I enjoyed baseball pretty thoroughly before all the impatient tinkering — is that it spotlights failure rather than success. With nobody on and nobody out, you’re hoping for a series of successes to put your team in the lead — say two singles sandwiched around a steal, or a pair of guys-swap-places doubles, or one of many other winning formulas.

But with a free runner on second and nobody out, you don’t need much in the way of success to grab the lead. A grounder to the right side and a medium-distance fly ball will suffice, with the same equation holding for the other team. And because the odds favor that run scoring, rather than hope for two or three good things in close proximity, you’re dreading that your team will fail. A run coming home isn’t a success to savor, but a disaster avoided. It usually takes a lot less time, which MLB’s committees of MBAs consider a plus, but it’s an upside-down, faintly sour experience, one that isn’t going to make anyone yell, “Free baseball!”

That was running through my mind in the 10th: I exulted behind the wheel as Jose Iglesias drove in Tyrone Taylor and replaced him at second, then despaired when Jeff McNeil popped up a bunt — because, again, the assumption is the other team will cash its own gimme run, meaning anything less than a two-run inning is perilous. Lindor grounded out, and there was that dread again, despite the Mets being up by a run.

Fortunately the roof was about to cave in on Robert Garcia and the Nats. Boom! Nimmo doubled in Iglesias. Pow! Mark Vientos brought in Nimmo. Zip! Pinch-runner Ben Gamel stole second. SOCK! Pete Alonso drove one over the fence.

The Mets had scored five runs, though of course being Mets fans we were all thinking that the night before they’d scored six and before that one ended we were all wondering if scoring 60 would have been enough. But this time there was no meltdown: Dedniel Nunez (whose arm has got to be feeling a little dedniel by now) set the Nats down 1-2-3, with their Manfred man left standing useless and disconsolate at third.

It was fun — a half-inning that features your team and goes on for 15 minutes or so is almost always fun. But I kept thinking that innings like that used to be more fun, back in the days before everything got fixed.

by Jason Fry on 1 July 2024 11:05 pm The Mets and the Nats, sheesh. I guess it proves that for every Nieuwenhuis there’s a Suzuki. And for the critical stretches of Monday night’s mildly bonkers game, it wasn’t clear whether the compass was going to wind up pointing to N or S.

And I missed the first five innings! I mean, so sue me — we were eating lobsters on the dock with Emily’s parents (actually I was eating fish and chips, due to a shellfish allergy) and I’d forgotten it was a 6:45pm start. Not to deflect attention from my lack of said, but isn’t that a little early to start a game anyway? 7:05, 7:10, even 7:40 I get … but 6:45 is just weird.

Fortunately, all I’d missed was the Mets being frustrated by MacKenzie Gore. I’d just gotten the TV on (accompanied by a gorgeous Maine sunset) when the Mets rose up in indignation, with Mark Vientos singling in Harrison Bader to bring the Mets within one, Tyrone Taylor reaching on a CJ Abrams error and Francisco Alvarez lashing a Derek Law cutter that didn’t cut into the gap for a 3-2 Mets lead.

It looked like the Mets might hold that lead, with Dedniel Nunez taking over for David Peterson and collecting four outs, leaving the Mets with four to get. But then Nunez walked Jesse Winker and Joey Meneses smacked a single to right field that took a strange bounce, startling a perhaps not completely attentive Taylor. Just like that, the Nats had tied it, and the ghosts of the last two days were suddenly romping around, cackling predictions of doom.

Nunez survived when Ildemaro Vargas inexplicably tried to bunt for a hit (seriously, WTF?); Jake Diekman came in for the ninth and immediately put the Mets in harm’s way when he threw away a ball, allowing newcomer James Wood to reach second with nobody out. The Mets survived when Taylor just barely corralled a drive by Jacob Young and we were on to extras, with Francisco Lindor once again the Manfred man.

This time, the Mets unloaded: Down 0-2 against Hunter Harvey and mired in an 0 for 12 funk, J.D. Martinez got a splitter that hung in the middle of the plate and drove it over the fence for a three-run homer. Alvarez brought in Taylor with a triple, and Jose Iglesias followed with a two-run blast. The Mets had driven in six runs, and Gary Cohen was exulting about putting the hammer down and cappers.

To be fair to Gary, so was I and quite possibly so were you. But Tyler Jay gave up a pair of walks and a pair of doubles and looked like he couldn’t get enough air out there, despite Alvarez trying to cajole, entreat and bully him across the finish line. (Alvarez is must-see TV, whether he’s show-ponying his way around the bases after another big hit or behind the plate tending to a reliever who’s become a spooked horse.) Jay was excused further duty in favor of Reed Garrett, who hasn’t been scintillating of late and was facing the tying run in Keibert Ruiz.

Ruiz singled in a run and the Nats were a drive down the line away from tying it and a home run away from showing the Mets the Full Suzuki, and if you were confident, well, I want to have what you were having. So of course Garrett made short work of Luis Garcia Jr., erasing him on a splitter to secure the victory. The lesson, as always: Never try to outguess baseball. The Mets had won despite playing reliever roulette with four or five rounds chambered; they’ll now undoubtedly make a slew of new moves in hopes that a few more of those chambers come up empty around 8pm Tuesday.

We won. Was it fun? It was at times. Were there times when I thought the best course of action was to slip into the other room and turn my stomach inside out? Yes there were. And that was not fun.

Let’s just say it … was a lot.

by Jason Fry on 30 June 2024 10:20 pm Since we’re Mets fans, we all knew the bullpen had issues. Since we’re adults, we all know progress isn’t always or even usually a smooth arc — it comes with fits and starts.

A day after blowing a big lead because of a nightmarish inning of relief, the Mets endured a bunch of bad luck, came back to tie it, had the game gift-wrapped for them, failed to capitalize on it, and saw another nightmarish inning of relief.

Oof.

I’m up in Maine, and the first half of the game was glimpsed during and between chores — which meant lots and lots of shots of Luis Severino looking perturbed and trudging around after yet another Houston hit felled in. I was at my station when the Mets launched a furious comeback, with Brandon Nimmo’s swing and a drive the exclamation mark.

And then? Weather delay. A very long weather delay — a whole game’s worth, in fact. The game came back while we were in the car seeking dinner, and proceeded as an animated Gameday rectangle in the pub we like a few towns over.

We shrugged when the Astros cashed in their Manfred man, then exulted when Nimmo immediately switched places with Francisco Lindor. A bunt and a sac fly, a grounder to the right side and a contact play … there were so many ways to emerge with a victory, and yet none of them materialized. J.D. Martinez’s bat has cooled from incandescent, as will happen; he struck out. The Astros walked Pete Alonso. Harrison Bader grounded out, moving up the runners for Mark Vientos. Vientos has had a helluva month, but this is baseball, where even the hottest hitter fails more often than not.

Vientos grounded out and the Mets had missed a layup. They brought in Matt Festa, whom I’d never heard of before today and learned was a Met around 4 pm. The roof caved in on Festa: three singles, a pair of lineouts, a double. Gameday’s version of this was a steady drumbeat of IN PLAY, RUN(S).

The Mets lost. They fell back below .500. A sour note to end one of the best months in franchise history, but in stoppering our ears lets not forget that last part. The conversation’s different. Summer baseball need not be pointless and obligatory. And the arc of the season may yet point skyward.

by Greg Prince on 30 June 2024 7:52 am In this new upbeat era of Mets baseball in which we only grimace ironically, let’s catalogue our positives.

Ty Adcock not only made his Met debut, but sparkled in it. Mark Vientos went about as deep as one can to dead center at Citi Field. Before Mark hit his mark, the Mets made the most of their luck in one particular inning (the second) and posted five somewhat improbable runs. The organization found space on its uniform sleeves for patches honoring the memories of Jerry Grote and Willie Mays as they continue to remember Buddy Harrelson the same way. And “OMG” continues to worm poppily in the ear of those who can’t help but be charmed by the Jose Iglesias experience.

So it’s not like Saturday was totally unpleasant.

I don’t know that I’d watched a game in 2024 brimming with expectations the way I did this middle contest Saturday. I expected the Mets to win. I expected the Mets to hold their 6-1 lead. I expected the Mets to push back on the Astros’ aspirations of catching up and going ahead. I thought about the standings and expected the Mets to gain ground.

Then I tempered my expectations bit by bit until I accepted that not every day is our day, even when for weeks almost every day has been.

If we’re looking for root causes, I suppose Edwin Diaz’s gunky hand and glove and the way the suspension they wrought brought about a reduced/diminished pitching staff sticks most. It’s a miniature 2023 out there in the bullpen, with everybody moving up a notch to compensate for Edwin’s absence, except we’re not allowed to fill in at the far back end of the relief corps, which is an issue when your starters throw a surfeit of pitches early and practically none by the sixth inning’s end. You really miss those marginal Syracuse arms when you are reminded they are better than nothing.

So, in the realm of faint praise, is Tylor Megill, who spells his first name with an ‘o,’ vowels his last name with an ‘e’ and an ‘i,’ and continues to have a career best described as Quadruple-A. As part of my newfound optimism, I thought Megill would shine against Houston if just to compensate for the cloud his previous performance cast over Chicago. I stand corrected. Megill gutted out five-and-a-third. The fourth was the discouraging one, with three painful Astro runs cutting the Mets lead to 6-4, and a sense emerging that, nope, this one wasn’t going to be as easy as everything to that point had looked.

Once Tylor was lifted after 101 stressful pitches, the bullpen shorts were showing. In the latter part of the twentieth century, where I lived until the millennial odometer turned, a seven-man pen was a luxury. Mostly it was unnecessary. Today I’m still shocked at how high and dry it can leave a team, especially if, god forbid, enough of the relievers in captivity have pitched lately. This one is unavailable. That one is unavailable. The safety net feels preemptively shredded. Even if you get an Adcock to come in out of nowhere and preserve order (we did), you still have innings to go before you can sleep.

And it becomes a nightmare.

I was under the impression Jake Diekman was one of those veteran lefties who would be über-dependable à la Brooks Raley. Alas, not all southpaws who’ve been in circulation forever are created equal. We miss the contributions of Raley. We’re still waiting for some on a consistent basis from Diekman, who was characteristically wild before giving way to Reid Garrett. Garrett faced three batters. It felt like three-thousand. Before Jake and Reed were done missing the strike zone, the Astros were ahead and I was missing more than ever Raley, Sean Reid-Foley and the likely Tommy John-bound Drew Smith. Goodness knows I’ve tensed up at the sight of Drew across his up-and-down tenure since he alighted in Flushing in 2018, but whoever isn’t coming in in the seventh typically looms as the much better option than whoever did enter, especially on a day like Saturday.

In the end, the Mets lost, 9-6, to a quality opponent, much as the Astros lost the night before to a quality opponent, which was us. We’re in that league now, safely removed from the ranks of Rockies and Marlins and anybody judged chanceless, but we haven’t ascended to the circuit where we never lose. We’re not yet that good. Nobody is, though I was at the precipice of believing our June ascent would proceed without pause clear to July. We were gong to win our fifth in a row in a fifth different jersey (I was even getting used to the City Connects). We were going to slip ahead of the Cardinals by a percentage point or two and hold the third Wild Card spot, for whatever that was worth. We were going to start breathing in the vicinity of the Braves’ necks, even. Didn’t happen. Or it hasn’t yet.

This taking the Mets seriously as a good ballclub is different from how I was expecting the balance of the season to play out. It’s more fun than what I figured we’d be relegated to. But it doesn’t preclude angst and disappointment on a given day when expectations aren’t shall we say Met. I vaguely recalling seasons working this way. Thanks for the emphatic reminder?

|

|