The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 29 June 2024 10:04 am I won’t claim it’s high on my lengthy list of Selig/Manfred era outrages, but it annoys me that the Astros are in the American League. They’re our expansion siblings, after all, arriving along with us in 1962 as the Colt .45s.

We began as a novelty act to salve the still-fresh wounds of Dodgers and Giants fans, fielding an Old Timers’ Day lineup complete with taking the Polo Grounds out of mothballs; they started life as the Colt .45s, a mildly shameless bid for a business tie-in that would lead to a more shameless (and more enduring) rebranding based around Houston’s ties to the astronaut program. In our first go-round we finished 10th and became synonymous with baseball futility; they were merely bad and finished eighth.

(Side note: Holy cats were the ’62 Cubs horrible.)

Rusty Staub and Jerry Grote were early Colts/Astros. Later, the likes of Ray Knight and Mike Hampton passed through the Astrodome before becoming Met heroes. John Franco and Dwight Gooden played in Houston at the tail end of their careers, cameos that would make you go “oh yeah that’s right” when looking up their stats years later. Donn Clendenon didn’t want to play for the Astros at all, a drama that eventually led to his becoming a critical ’69 Met. We faced them in ’86, when their rotation was anchored by scuffballing former Met Mike Scott and ’69 hero Nolan Ryan, and prevailed in an exhausting sixseven-game Gotterdammerung.

All that has become so long ago that I feel like I just put an onion on my belt and gave a stemwinder about bees and quarters. The Astros have been in the American League for more than a decade now and become synonymous with cheating; opposing fans will be making jokes about trash cans decades after Jose Altuve is a white-haired Hall of Famer visiting a suite to glad-hand with oil executives. These days, sadly, I hardly think of our ’62 siblings at all — they’re far away and play in that jumped-up arriviste beer league, so why would I?

But 2024 has offered more parallels.

The Astros have exhausted their fans with a season of stops and starts and ups and downs, navigating injuries and tough personnel decisions, but they’d heated up of late and arrived for Friday night’s game with a record of .500 — not exactly world-beating stuff, but cause for celebration given where they’d been.

That’s our 2024 bio as well.

Baseball specializes in these something’s gotta give meetings, and momentum favored the Astros immediately: Five seconds into the game, Altuve had whacked a Jose Quintana sinker that didn’t sink into the stands for a 1-0 lead. But as has been a Mets hallmark of late, Quintana staggered out of the first inning weary but whole, giving up only the one run. The Mets loaded the bases with nobody out in their half of the first against Ronel Blanco and came away with only one run, but hey, that did tie it.

Houston took the lead again in the third, lost it in the fourth on a Tyrone Taylor solo shot, and then the roof caved in on Blanco in the sixth: Pete Alonso‘s overly aggressive first-inning AB had not exactly been a highlight, but now he hit a no-doubter to left to give the Mets the lead; four batters later Jeff McNeil golfed a ball into the right-field corner for a three-run homer and the Mets were up by four, on their way to winning by five.

McNeil would wind up three for four on the night, continuing a run during which he’s looked at least a little like his old self. Maybe that’s too little too late; maybe the knowledge that Brett Baty is playing second in AAA and tearing it up has concentrated the mind wonderfully. If nothing else, McNeil can look around and see plenty of teammates who’ve extracted themselves from the fan scrap heap and revitalized their seasons.

The Mets, at least for the moment, look thoroughly revitalized: After the game, Jose Iglesias AKA Candelita offered the Pride Night crowd a mini-set formally unveiling “OMG.” Watching a backup infielder perform his latest single in his stadium accompanied by adoring teammates is a new one for me, but it’s this week’s second never-seen-that-before video to have me laughing happily: During Wednesday night’s monsoon delay, fan video caught Grimace on the Shea Bridge, up on people’s shoulders shotgunning a beer before a cheering throng; as I stated on former Twitter, if that doesn’t lead the 2024 World Series Champions video, we riot.

That’s getting ahead of ourselves, of course, which leads me back to what exactly, this smidge-over-.500 team is.

Two perspectives may be at least mildly helpful.

The first comes from Joe Sheehan, to whom you should absolutely subscribe: “[T]he 2024 Mets are this year’s best argument for one of my guiding principles: Let the season breathe. This is what baseball teams do, they look good for a while, look bad for a while. The in-season variance of a baseball team’s performance is bigger than whatever you think it is. The Royals backed up 34-19 with 8-18. The A’s went 17-17, then 12-37. The Yankees have dropped ten of 13 after a 49-21 start and bodies are piling up in the Harlem River. Breathe. It’s not football.”

That’s excellent advice. And yet I’ve also thought back to something Greg said a few years ago. At the time I’d decided I needed to be better at analysis and was unhappy with how many of our recaps were essentially reactions. Greg heard me out quietly, then said: “We’re fans. That’s what we do. We react.”

Indeed we are, and indeed we do. There’s a value to understanding that a night’s bullpen meltdown doesn’t foretell doom just as a walkoff, come-from-behind three-run homer doesn’t print its own playoff tickets. But in the moment that’s not going to be anyone’s reaction. Nor should it be.

We’re fans. We react. Right now we get to react to rain-delay Grimace appearances and postgame concerts. That’s extraordinary; let’s just enjoy it.

by Greg Prince on 27 June 2024 10:10 am They’re probably not this good, are they? How could they be? Fifteen wins in nineteen games seems to give us all the answer we need, a stretch that’s unfurled since their last pairing of consecutive losses, not to mention the active streak of three victories during which the most recent ascension or explosion feels it can’t be topped, yet the next day it is. The odds say sooner or later the Mets who are making a science out of finding ways to win will accidentally lose a game, and from there a few balls will bounce in their opponents’ favor, and suddenly…

Welcome to the inversion. The above paragraph was written just over a month ago, except on Opposite Day, when every positive about the Mets now was a negative about the Mets then, meaning we used words like “bad” and “lose,” if you can remember back that far. There were a lot of Opposite Days for the 2024 Mets, who once relentlessly depressed us, which seems impossible, since we now know them only for relentlessly uplifting us. You know how the temperatures have been in New York lately. The Mets are playing at a crisp 180 degrees from where they were in May when we decided they were going to stay ice cold for the duration.

Instead, they’ve burned a path through June. From a nadir of 24-35, they have risen to 39-39. It’s a plateau that looked like Everest when they gathered at base camp to make this particular climb. Surely .500 wasn’t their goal. It was too high. Yet here they are, planting a flag for the moment atop Mount Break Even.

How did we get here? Why ask how? Team meetings, licensed characters, progression to the mean…take your pick. I choose to process what’s happening without questioning it too much. When the Mets were dreadful, that looked like what the Mets were. Now that the Mets are marvelous, I think I’ll just marvel at them.

Wednesday night, the only thing the Mets did wrong was get rained on. Shocking to realize they can’t overwhelm the weather as they do their opposition, but give them time. The 87-minute precipitation pause probably cost callup Ty Adcock his Met debut (he was warming in the pen when the tarp rolled out at Citi Field) and it made staying awake a challenge for some watching from home (I snoozed through the seventh), but the club’s momentum never dampened. Up 4-0 on the Yankees in the bottom of the fifth in what was already an official game, the Mets came back once the grass was sufficiently dry and ground their municipal rivals into the dirt. Eventually, it became an official ass-kicking, with a final of Mets 12 Judge 2.

Sean Manaea walked a few too many of the nettlesome neighbors, but that’s what double plays are for. Sean threw three pitches that each turned into a pair of outs. “Just the Two of Us,” indeed. With the lead up to 7-0 following the weather delay, Danny Young did what pitchers everywhere do: he gave up a home run to Aaron Judge with Juan Soto on base. As long as Judge couldn’t hit an eight-run homer — and not even he can do that — we were gonna be OK. We’d already had a long ball from Francisco Alvarez and were going to get one apiece from Tyrone Taylor and Harrison Bader, although I napped as the latter flew. There were all kinds of other runs and runs batted in, and there was Adrian Houser, once upon a time the internal bane of our existence, now closing out a three-inning save and a Subway Series sweep.

Could a person want more than a ten-run throttling of the so-called Bronx Bombers, described to us by the best booth in town? Well, I always want to add to the all-time Met roster, and though I was deprived of typing in the name “Ty Adcock,” I did get to expand the mothership of lists to include outfielder Ben Gamel, who checked in for defense in the ninth to become Met No. 1,240 overall. And will ya look at that: a “24” right in the middle of Gamel’s chronological ranking, apropos of Michael Mays, amid a group of dignitaries (including Cleon Jones) wearing Mets No. 24 jerseys, throwing out the first pitch Wednesday evening in memory of his father Willie. Isn’t it beautiful how the Mets’ institutional amnesia that the Greatest Ballplayer Ever played for them has lifted and stayed lifted?

Isn’t everything beautiful about the Mets as we speak? Is it baffling that such sentences are being composed? From the perspective of earlier in the season, absolutely. But the season went on and the Mets did, too, becoming something wholly different from what we were sure they were. Emotional cost certainty is in flux as a result. That’s the potential downside of any surge from nowhere to somewhere. I read something in April about fans of really good teams and fans of really bad teams being able to deal with losses better than fans of .500 teams, because if your team is really good, one loss is a veritable little fish within a great big pond of wins, while if your team is really bad, one loss is just one more loss that doesn’t surprise you in the least. The fan of the .500 team, however, sees any given loss as a referendum on the course of the season. Are we really this bad? Are we really this good? We don’t know. The finding out suddenly has stakes.

Which, we are beginning to be reminded, is why they play the games. The Mets’ arrival at .500 coincides with the recognition that there are definitely teams in this league and, for that matter, the other league who appear not quite as good as them, but very few who seem all that much better. The Yankees are the latest powerhouse we’ve faced that is obviously headed to the postseason, yet clearly isn’t impervious to injury or imperfection. All among the Braves, Phillies and Dodgers have struck me the same way. Incredible talent at the core, but if they’re dinged up enough, they have depth issues like anybody else. Of teams against whom the Mets have gone head-to-head to date, only the Brewers, who we played so long ago it was March, and the Guardians have come across (to me, anyway) as in a league of their own. Teams get hot, teams cool down. We’re about to welcome in the steaming Astros, who were twelve under .500 in this very season, ebbing lower than even us. They’re now where we are.

Can our .500 club, having passed a passel of NL wheel-spinners to become what would have to be objectively considered a playoff contender, actually continue to be, you know, this good? We are not impervious to injury or imperfection. We are still without our closer. We are also without two other bullpen mainstays in Sean Reid-Foley and Drew Smith, the latter having gone on the IL Wednesday, which explains why somebody like me is closely monitoring the movements of Ty Adcock. Ben Gamel is here because Starling Marte isn’t. Yet we’re not really missing anybody the way we’ve been playing as a whole. No Edwin Diaz amounted to no problem for two nights as we constructed leads so tall not even Hammerin’ Yank Aaron could completely cut them down to size. Everybody but Jeff McNeil is hitting consistently, and McNeil’s bat, as evidenced by the deep lineout that brought home a run in the New York-New York finale, is showing a bit of a pulse, too. Yet the collective sizzle will at some point fizzle. That’s not glass half-empty fatalism talking. It’s simply what happens in every season. The collective fizzle turned to sizzle. It was bound to happen, regardless that there was no sign it would.

Every season it’s like this, if not necessarily in a fashion as extreme as 0-5 followed by 12-3 followed by 12-27 followed by 15-4 to get to 39-39. Downs. Ups. Frustration. Elation. Not knowing exactly what comes next. Not knowing exactly how we’ll handle it. Not knowing if we’re really as bad or as good as we’re certain we are or if we’re just prone to taking a wildly divergent route to middling. Again, that’s why they play the games.

by Jason Fry on 26 June 2024 8:09 am I stopped attending Subway Series games years ago because they’re like Thanksgiving dinners where every single uncle and cousin you dislike RSVPs that they’ll show up drunk and eager to talk politics. No thanks — I’ll catch these from my couch, where any woofing mookdom can be addressed as an internal affair.

That part’s predictable; the rest of a Subway Series game isn’t. I certainly didn’t have David Peterson pulling a Houdini after facing bases loaded and nobody out, a sequence that started with a first-pitch single to Anthony Volpe and a pitch-clock violation, meaning Peterson was somehow stuck with a runner on first and an 1-0 count to Juan Soto after one pitch thrown. Though calling what Peterson did a Houdini act misses the important lesson: Peterson trusted his stuff and so struck out Gleyber Torres, Alex Verdugo and old friend J.D. Davis.

Another thing I hadn’t predicted was Gerrit Cole reporting for duty first without his location and then without his velocity. The location issues led to a trio of first-inning walks, with Francisco Alvarez coming back from 0-2 in another cool and collected AB, and a run when Tyrone Taylor punched a ball through the hole, though Pete Alonso was thrown out from you to me at home to short-circuit further celebrations. Cole had been touching 98 in that inning but came out for the second with his fastball much reduced, and he paid for it: Mark Vientos and Harrison Bader took him deep, with Vientos and Brandon Nimmo unloading on him in the fourth. It’s not our problem, but Cole is either not ready or not right.

Vientos, on the other hand, is turning into a monster, losing balls with a bat in his hands and not losing as many balls as we’d feared while wearing a glove. His growing confidence has been great fun to watch, to say nothing of how his more formidable bat has made the lineup deeper and more dangerous. (I’ll spoil that a little by admitting there’s probably an April recap in which I say something similar about Brett Baty.)

Peterson started leaking oil in the fifth and was excused two outs from the long side of a 6-1 decision — Carlos Mendoza has never shown the slightest interest in making moves based on the win rule. Dedniel Nunez needed just one pitch to coax a double-play grounder from the Solar Bear, and when the Mets added three more runs against momentary Met Phil Bickford it looked like we’d enjoy the rest of a laugher, with SNY doing its part by offering loving montages of Yankee fans slumped at Citi Field looking variously sullen and stoic.

(Speaking of which, it’s remarkable how intertwined the 2024 rosters are. Mendoza was Aaron Boone‘s bench coach, of course, but the Yankees roster includes former Mets Davis, Bickford, Michael Tonkin and Marcus Stroman, while the Mets employ former Yankees Bader, Adam Ottavino, Ben Gamel and Luis Severino, with Luis Torrens having arrived from their minor-league system.)

The laugher dissolved as everything fell apart in the eighth. Ottavino didn’t have it, Danny Young didn’t have it either, and with the bases loaded Reed Garrett was summoned to face Judge. Garrett immediately got to 0-2, albeit on a pair of cutters that sat in the middle of the plate, and Alvarez called for a fastball up and in, a waste pitch intended to push Judge off the plate and change his eyelines, setting up a cutter low and away.

That’s been a solid plan since the ball got lively a century ago, but Garrett missed his catcher’s up-and-in target by two feet, leaving a fastball in the middle of the plate; I’m pretty sure I let out an eeep! even before Judge swung. It looked like Bader would corral it deep, though he wasn’t doing his foot-crossing backwards prance, a play dripping with mustard that always makes me laugh. That was a sign of trouble; so, it goes without saying, was the ball plopping over the fence for a grand slam that cut the Mets’ lead to a definitely eeep!-worthy 9-7. The Yankees are a billion games over .500 for a reason, and any lead that will be contested by Soto and Judge should come with that rearview-mirror warning made famous by Jurassic Park: OBJECTS IN MIRROR ARE CLOSER THAN THEY APPEAR.

Garrett spent the top of the ninth stomping around in the dugout, no doubt thinking about what he’d done; I’d have preferred watching him exhale after the Mets put up, oh, six or seven more runs, but ’twas not to be. Also not to be, fortunately for him and for us: a Yankees lineup with Giancarlo Stanton and Anthony Rizzo. Garrett retired Verdugo on a first-pitch liner to Alonso, got a grounder from Ben Rice, and fanned DJ LeMahieu to secure the win.

Exhalations on the couch! High-fives all around! Though mostly I was just tired — the Subway Series will do that to you, regardless of your vantage point.

by Greg Prince on 24 June 2024 11:08 am The part where the Mets hit three home runs; receive a practically flawless performance from their starter; and win is the best part from Sunday night at Wrigley Field. Sadly, it’s not the main part. The main part is the part where the umpires inspect the Mets’ closer’s glove and pitching hand and tell him, nope, you can’t come in, you’re out of the game, and you’ll find you’re about to be suspended for ten more games on top of this one when you didn’t even get to pitch as planned.

That’ll take the edge off a good night, eh?

There’s no getting around the impending absence of Edwin Diaz for something that had nothing to do with jumping around on a WBC mound or a shoulder impingement. Just as Sugar seemed to be rounding back into Narcoesque form, the cops come and get him for having a little too much stick-to-it-iveness on his person. Per the pool report (required for simple communication with the media and therefore the fans because umpires are more imperious than the bleeping Supreme Court of the United States), crew chief Vic Carapazza reasoned, “It definitely wasn’t rosin and sweat. We’ve checked thousands of these. I know what the feeling is.” Well, that’s ample enough evidence to bleep over a team just finding its footing, ain’t it? Whatever the umps told Edwin, “go wash your hands and we’ll try this again” apparently wasn’t one of their suggestions.

Diaz, like Max Scherzer and Drew Smith before him, said the sticky-substance ejection followed him doing absolutely nothing different from usual in his routine. Smith, who substituted on no notice for Edwin in the ninth, said that after his 2023 ejection and suspension, he changed absolutely nothing about his preparation. Drew hasn’t been ejected since. He, like every pitcher, gets checked every time he goes to the mound. One time he got nabbed, as if the umps had a quota to fill before the end of whatever month. In this era when “accountability” is so valued by this ballclub, maybe one of the Mets’ umpteen coaches should be responsible for a glove & hand inspection of each pitcher prior to every inning before the umps get their gander, just as a precaution. Pretend it’s a new base hit celebration and the whole team will be into it.

Barring an unlikely successful appeal of the sticky-stuff ruling, the Mets will be sans Diaz for ten games and won’t be permitted to replace him on the roster. No time is ever good to be shorthanded, let alone without your ninth-inning man, especially when the team is playing well enough to be nursing leads of three runs or fewer as games near conclusions. The fireman’s role figures to be up for grabs this week and next. Drew didn’t exactly lay down a marker versus the Cubs, getting pulled with two out and a runner on first, shaking his right arm a bit during his surprise outing. Lefty Jake Diekman came on to finish, and he did. We’ll see who gets the ball when.

Too bad about all this from multiple angles, including that it makes a Mets fan forget what a good game we saw Sunday, despite ESPN’s involvement in telecasting it. Back-to-back homers from Francisco Lindor and Brandon Nimmo in the third made the score 3-0, and we never trailed from there. J.D. Martinez produced the most useful of groundouts to extend the lead in the fifth. When Luis Severino sat down after six shutout innings (10 Ks), the Cubs were so energized, they nicked Dedniel Nuñez for a pair of runs. Mark Vientos sapped half that life out of them by responding with a ball hit so far that it was out of the reach of any bleacherite wishing to fling it toward the grass.

We didn’t even pay a karmic price for two terrific defensive plays by 2020 Mets first-round draft choice Pete Crow-Armstrong, who, you’re probably aware, was traded to the Cubs in one those Win Now moves that didn’t result in winning then. The most impressive of the PC-A gems was a throw that nailed Francisco Alvarez going from second to third on a single, which is something a baserunner usually does with zero hassle. Earlier in the season, you could picture that sort of basepath blunder blowing up in our collective face. Sunday it was simply isolated fodder for The George Michael Sports Machine of the mind’s eye.

Yeah, good game (5-2), good series (two of three), good road trip, (four of six), good place in the shall we say fluid Wild Card standings (one out of a playoff spot, not behind too many combatants). Not a good development with Diaz, however. Maybe we shouldn’t sweat it too much. If we do, we, too, might get thrown out.

by Jason Fry on 23 June 2024 9:19 am By the time Saturday afternoon rolled around our 2024 beach vacation was at an end: house cleaned, last Long Beach Island breakfast consumed, farewells said, and car filled for the trip back to Brooklyn, the heat wave we’d been happy to miss, and normal life.

Heading up the Garden State Parkway, your correspondent was frankly weary. You’ve been there: thoughts wandering, eyelids heavy, brain feeling full of static so that bearing down on the task at hand is faintly painful. I was weary and it was going to get worse before the obvious remedy made it better.

I should stop, I thought. Which was good advice and the responsible thing to do. But we weren’t that far from home. We had things to do. And there wasn’t a good alternative. Emily was asleep in the passenger seat, head bent at an angle she’d complain about once fully awake again. The kid doesn’t know how to drive yet, and I doubted a helicopter zooming overhead would drop down a learner’s permit and an instructor. Nope, this one was on me.

I decided I’d stop at the Jon Bon Jovi rest area (yes it’s a real thing) if I wasn’t more awake by the time I approached it, and flipped over from a Spotify playlist to MLB Audio, as the Mets and Cubs were preparing to resume hostilities at Wrigley.

Ten minutes later, I was sharp and alert. The JBJ rest area went by without us, perhaps awaiting Tommy and Gina at the end of their long days spent at docks and/or diners. To them and all other weary prayer-livers, whoo wah oo wah oo wahooga.

What had changed? I was laser-focused on my irritation with Tylor Megill, who’d given us the full Tylor Megill Experience in a nightmarish first inning: nibbling and missing, nibbling and missing, until five runs were home and I wanted to jam a spork — made in whatever country — in my eye. Just like that, we’d gone from a laugher so nice we had to recap it twice to being the laughee and looking to Sunday for redemption.

Still, by the time it was mercifully over I was home and alive, people and automobile intact. Thanks for that, Tylor, even if you can keep the rest.

by Greg Prince on 22 June 2024 6:58 am “Solstice schmolstice,” they might say in the bleachers at Wrigley Field, where the exact position of the sun doesn’t matter as long as it’s out somewhere. They have their new tradition of building a cup snake that wends all the way to Lake Michigan, perhaps Michigan itself, and they have their old tradition of throwing back the baseballs hit at them by Cub opponents. Both traditions got a workout on Friday. Hope you had some version of summer hours and got to take it in in all its Metsian glory.

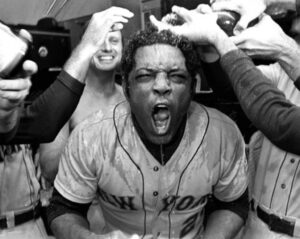

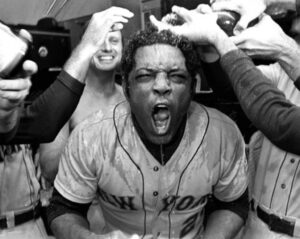

The Mets enjoying themselves in the visitors’ clubhouse is the best of Wrigley Field traditions. In the ballpark where Willie Mays dressed for the final time as a regular-season active player — he was a dugout spectator on October 1, 1973, as his Met teammates completed fighting for themselves en route to an NL East title, then a teetotaler taking a cold champagne shower in the jubilant visitors’ clubhouse — the Mets threw a first full day of summer cookout, grilling phenom Shota Imanaga for ten runs in three-plus innings. Given that Imanaga had the Mets roasting on a spit at Citi Field several weeks earlier, the main course was quite satisfying. Runs in each of the first four innings. Multiple runs in three of them. Souvenirs for reluctant recipients in those far away seats via the good graces of J.D. Martinez, Francisco Alvarez and Brandon Nimmo. Between the stacking of empty beer cups, each baseball the Mets deposited was marked RETURN TO SENDER. Sure, whatever. The runs the homers represented stayed glued to the scoreboard.

Four RBIs for Martinez. Three for Jose Iglesias, who recorded four hits and the ditty teammates love to blast when they’re done blasting the likes of Imanaga. Six-and-a-third innings of cool, calm professionalism from Jose Quintana, who allowed just one run and struck out eight. Competent relief from both Adam Ottavino and Drew Smith, putting the kibosh on any idea that this was going to be one of those Wrigley days when no window on Waveland Avenue is considered safe. Nope, only the Mets found the wind blowing out, gusting to an 11-1 romp. The end result was never in doubt. The last of the lingering intrigue, beyond whether Steve Gelbs would abandon his play-by-play post and race to cover his beloved cupathon (focus, Steve, focus), was whether we’d see two catchers in particular.

And we did. We saw Joe Hudson, a career journeyman on a weekend pass to the majors because Luis Torrens took a couple of days of paternity leave. Hudson caught the Mets’ final defensive half-inning, action enough to qualify him as Lifetime Met No. 1,239. Joe didn’t get to bat in what might be his only Mets game, temporarily placing him in the company of another Joe H. who crouched behind the plate without getting to stand beside it, the immortal Joe Hietpas amid the last wisps of 2004, a decidedly less jubilant season-ending occasion than the one that soaked Mays in 1973 (though Hietpas can probably still taste the cup of coffee and consider it champagne). Hudson bounced into the Met organization in April courtesy of the Cubs when the Cubs signed Silent Generation expatriate Ali Sanchez, our 2020 cameo catcher who has since been sent from Chicago to Miami, which in turn created Cubbie-hole space for none other than Tomás Nido, the other catcher we wondered if we were going to get to see on Friday. We did when he pinch-hit with two out in the bottom of the ninth. Nido didn’t respond to the sight of the only team for whom he’d ever played the way Mays did when he homered for the Mets against the Giants in 1972, but three strikes before he ended the game, I gave him a quick Old Friend™ series of claps from my couch. He probably didn’t hear them.

Tomás is an ex-Met after eight seasons of being true blue and orange (his MLB debut came on the wrong end of a 17-5 blowout at Wrigley in September of ’17) because Torrens, when not off taking care of emerging daddy duties, usurped any need for the Met lifer who always did his best, which was, you know, Nido-level. Luis and Tomás shared catching duties for a brief interregnum before Alvarez was pronounced fit as a fiddle and in fine fettle. Francisco returned to daily catching and by some Amazin’ coincidence, the Mets have won practically every day with him fully present. Who knew one of the key players on whom we were relying at the outset of the season being out for an extended period would have a deleterious effect on the ballclub as a whole? God, it’s hilarious how we keep overlooking stuff like that. We didn’t have Alvarez, and we were a worse team. Martinez wasn’t quite ready to swing to his standards, and we didn’t look like we had much of a lineup. Iglesias? Wasn’t he a glove-first, singing-second guy? Now he, like Torrens, is quality depth; Alvarez is shepherding every starter; and Martinez lines the ball everywhere. Better components will do wonders for the collective unit.

It’s the second full day of a summer when we’re one of nine (!) teams within two games of a playoff spot. We’ve got time to figure out plenty. We probably won’t, but we’ll try.

Tom Seaver sought out Willie Mays as the Mets went suitably nuts at the winning of their demi-flag on the final afternoon of ’73. As captured by Mays biographer James Hirsch, Tom asked, “Where’s Willie?” Someone told him, “He took two sips of champagne and he passed out.” No, Willie wouldn’t have been much help draining beer cups in the Wrigley bleachers, but he could do everything else in a ballpark. Jeff Hysen and I reflect on his briliance in the new episode of National League Town, which you can listen to here or wherever you drink in your podcasts.

by Jason Fry on 22 June 2024 12:58 am Here’s a list of what I did Thursday during our week of vacation on Long Beach Island:

bike ride

pancakes

beach

hot dogs/beer

nap

more beach

mini-golf

tuna steaks/prosecco

ice cream

end of a ballgame

That’s a pretty damn good day, one I felt absurdly lucky to get to enjoy. The ballgame was the last couple of innings of the Giants and the Cardinals at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field. Which I savored, from the Negro League throwback jerseys and the views of the field to Negro Leagues Baseball Museum president Bob Kendrick telling tales of Willie Mays and Satchel Paige. I missed both Reggie Jackson‘s searing account of being a young ballplayer in the Jim Crow south as well as FOX’s inning of retro play by play, but what I did see made for a lovely capper to the day.

The only flaw? No Mets game to watch. The team was off, traveling from Texas to Chicago to start a three-game set against the Cubs.

Enter Friday, which offered many of the same activities from Thursday’s list, but added an ingredient that will make any day better: first watching and then listening to the Mets beat the living shit out of the Cubs at Wrigley Field.

The Mets hadn’t enjoyed their first look at Shota Imanaga back on May 1, when he allowed them just three hits over seven innings at Citi Field. On Friday they had three runs against him before he recorded an out, thanks to a leadoff double by Francisco Lindor, a Brandon Nimmo walk and a J.D. Martinez home run.

Imanaga looked frankly shell-shocked, perhaps by his first experience of Wrigley on a summer day with the wind blowing out, though his fastball missing a couple of ticks on it was also probably part of the equation.

In the bottom of the first, a Mark Vientos error on a muffed double play let the Cubs get one of those runs back, and with Jose Quintana on the mound I braced myself for one of those 14-12 Wrigley slugfests. But Quintana pitched superbly, allowing nothing beyond that first-inning unearned run, while the Mets kept pummeling Imanaga, with Francisco Alvarez and Nimmo homering, J.D. doing more damage and Jose Iglesias winding up with four hits.

(In an odd turn of events, the game ended with Drew Smith fanning old friend and brand-new Cub Tomas Nido, while Joe Hudson was making his Mets debut behind the plate. Hudson was in there backing up Alvarez because Luis Torrens went on paternity leave; three weeks ago, if you’d given Nido a glimpse into this particular future … well, he would have had many questions.)

I greeted the pummeling of the Cubs with glee, which left my kid a little baffled and so required an explanation, namely that when I was a young baseball fan, the Mets’ primary rivals were the Cardinals and the Cubs, and of the two the Cubs were far more loathsome, which is probably something I picked up from having read every quickie paperback about the 1969 pennant race and World Series. All of them included Ron Santo‘s habit of clicking his heels, something nobody seems to do anymore but I have always deeply disapproved of as behavior only villains would indulge in.

It was the Cardinals and Cubs who left Young Jason frothing with rage, particularly the Cubs, and particularly the Cubs if the Mets were playing them at Wrigley. Few things were more painful than watching some luckless Met starter get strafed on a windy day before the baying Bleacher Creatures; few things were more delightful than watching the Mets administer a proper Wrigleyville beatdown to render those Bleacher Creatures first sullen and then absent.

Friday was a proper beatdown in every facet. And that made for a damn good day.

by Jason Fry on 20 June 2024 11:10 am Being a fan is inherently ridiculous.

Two weeks ago we were collectively rending our garments because the Mets were painful to watch and we were killing time waiting to a) see what they got for every upright body at the trade deadline; and b) complain about seeing Pete Alonso in the togs of the Mariners/Cubs/Giants/What-Have-Yous.

Then came the Grimace era, which while barely a week old saw us think the Mets had figured everything out and were unbeatable — perhaps no more so when they coolly came from four runs down to shock the Rangers, perhaps by way of tribute to the now late, eternally great Willie Mays.

Wednesday night this rickety tower built from giddiness and recency bias and hubris all came crashing down, as the Mets suddenly looked very much like the Mets of two weeks ago vintage, failing to win an eighth straight and leaving Grimace with a pang in his big purple heart.

Defeat had a lot of fathers. There was Edwin Jimenez‘s improv strike zone, which was no help to a suddenly wild Sean Manaea in a profoundly irritating first inning. (While Jimenez was definitely bad, a bases-loaded HBP on an 0-2 count isn’t one you can pin on the umpire.)

The Mets fought back against Andrew Heaney, whose significant other really should tell him to lose his living-under-a-bridge beard, with Alonso’s homer to center giving them a 3-1 lead. But they gave it back in the sixth, with Sean Reid-Foley allowing the Rangers to tie it while looking out of sorts, prompting Gary Cohen and Keith Hernandez to speculate if something might be physically wrong. Something definitely wrong in that inning was the defense: First Starling Marte overthrew the cutoff man and Alonso made a weak throw home, and then Mark Vientos couldn’t corral a hot grounder in the hole.

The Rangers had tied it, and Drew Smith allowed them to untie it in the seventh, serving up a two-run homer to a slumping Leody Taveras. While I’ve never dubbed Smith a Jonah, I’ve also never trusted him, unless it’s to give up dingers every time a Mets manager decides he’s worthy of moving a step up the bullpen ladder. Giving up home runs is what Smith does; I hurled poorly sourced and unfair imprecations his way and hoped the Mets would come back, though I had an uneasy feeling that particular well of luck had run dry.

As indeed it had. The Mets came up in the ninth needing a bloop and a blast and got neither: Marte grounded out, Vientos got himself out with an overly aggressive AB, and Francisco Alvarez fought through a tough AB but grounded out.

You can’t win ’em all, a wise person once said — a warning probably first heard in Mesopotamia, soon after some bunch of marvelously Guillorme-bearded Babylonians decided to venerate Ishtar with a diversion involving a ball and a stick. It’s a warning we briefly thought no longer applied to us. Now, once again, we know better. Stupid real life!

by Greg Prince on 19 June 2024 10:14 am He who has led baseball in every meaningful way for generations has been reported to have passed away. If these reports prove accurate, protocol therefore demands the flag be lowered to half-staff, then ball must be played like it’s been played only once before — from 1948 to 1973. Play it like it was played in Birmingham; in Trenton; in Minneapolis; in Manhattan; in San Francisco; in Flushing. Play it like it was played everywhere Willie Mays called home, which collective experience specifies was every ballpark he ever graced. Willie competed in the uniform of just a handful of organizations, but his brilliance belonged to every fan. So to honor him, wherever you are and whomever you root for, please remove your hat, bow your head, picture No. 24 amid your reverent moment of silence, and then play ball. Play with style. Play with heart. Play with innate intelligence that divines every nuance of the game and use what you know to your and your team’s full advantage. Play with all the ability in the world if you have it (Willie did) or all the ability you can muster (Willie did that, too). Play with joy. Work relentlessly at being the best, but don’t give the impression it’s work. Play ball.

On Tuesday night, the same night it was announced Willie Mays had moved on, the last team for whom he played professionally displayed the kind of joie de ball that made the man immortal in every sense we baseball-loving mortals can fathom. The New York Mets trailed the Texas Rangers, 6-2, after five innings, yet came away the winners in Arlington, 7-6, posting their seventh consecutive victory. They hit; they hit with power; they fielded; they threw; they ran; they understood what needed to be done; and they did it. Maybe their caps flew off in the process. If it wasn’t a conscious tribute to the National Pastime’s head of state, it was as appropriate a performance as one could summon to leaven the aftereffects of the shocking bulletin we’d been reluctantly delivered.

Willie, they said, died at 93. It’s shocking regardless of age. You would have bet even money — an action MLB is cool with these days — that Willie was the one person who would defy standard actuarial odds. Ninety-three? Watch Willie go for a hundred and then keep going. Based on everything we saw and read since he entered our consciousness, he may be deking us at this very moment just so the trail runner can take third on the celestial relay.

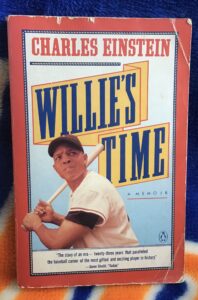

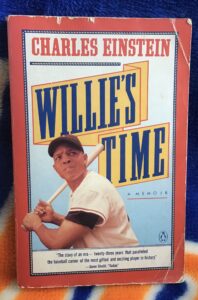

If this really is it, Willie still isn’t gone. Baseball is Willie’s game. Not was, is. We’ve lived in Willie’s time for so long, it seems impossible to reset our watches. There was baseball before him. There’s been Baseball with a capital Willie since. He linked every era so seamlessly that you’d almost think they’ve flowed as one. I’ve never existed a day when Willie Mays couldn’t be identified as the greatest ballplayer alive. I doubt I’m ready to start now. If this really is it, Willie still isn’t gone. Baseball is Willie’s game. Not was, is. We’ve lived in Willie’s time for so long, it seems impossible to reset our watches. There was baseball before him. There’s been Baseball with a capital Willie since. He linked every era so seamlessly that you’d almost think they’ve flowed as one. I’ve never existed a day when Willie Mays couldn’t be identified as the greatest ballplayer alive. I doubt I’m ready to start now.

Willie Mays came to New York in 1951 and put down psychic roots that outlasted both the Polo Grounds and Shea Stadium. Both parks were better off for his presence. The New York Giants, as proud and historic a franchise as ever was, personified past glory before Willie showed up. Willie made them vibrant and contemporary and winners. They left town, anyway. There are many reasons to fondly recall the New York Giants of 1883 to 1957. The first and sometimes only one people know in this century is Willie Mays.

We weren’t done cheering for Willie just because his jersey didn’t say NEW YORK on it when he returned to the old neighborhood or brightened the new environs. No “visiting” player was ever as thoroughly or sincerely or consistently embraced as Willie Mays was when he was technically a Met opponent for a decade. That’s because he was never more than technically a visitor. How could he be? He’d never stopped owning New York.

It’s wrong that the Giants ever departed New York. It’s wrong that Willie had to be anything but a Giant. It’s absolutely right that Willie Mays was a New York Met. There’s an awful lot of “you had to be there” to explain what it meant to see No. 24 rendered in orange and blue and Willie elevating the color scheme to a whole new level in 1972 and 1973. You had to know a little something about where Willie had been prior to San Francisco and how New York couldn’t forget him. Even if you were a kid of nine or ten, you got it and you were all in on what was happening. Willie Mays was here in front of you, not for a series, but for a season, then another one, then the postseason that followed. You knew it was late for him as a player. You heard it wasn’t the same as it had been when he arrived twenty-some years earlier. You, quite frankly, didn’t care. You got Willie Mays in your midst. You were blessed by the glimpse and you never forgot it.

When his career was over, a trope emerged that 42-year-old Willie Mays had stayed in the game too long. The next 51 years revealed Willie could stay as long as he liked, wherever he liked, however he liked. By outliving every ballplayer considered something akin to his peer, appreciation of Willie Mays as singular revived and amplified. The Giants, despite their sin of going west, took care to burnish his vast legacy. The Mets, once the proper people had their say, threw in their 24 cents on preserving his place in history. Film clips survived. Some were in black and white. Those that were in living color turned grainy. If you were shown video evidence of what Willie Mays was all about, you tended to see just so much. Unless you were regularly in those ballparks he made his, you could only imagine what he was really like to watch every day in his extensive prime. You could only listen to what was said about him doing the impossible. You could only read the breathless accounts and attempt to comprehend the breadth of his statistics. You didn’t get a nonstop stream of Willie Mays content as you would have had he come along in our time.

Maybe our loss. Probably his gain. This way he’s a legend with just enough evidence to back up the stories we’ve had handed down to us and take pleasure ourselves in handing down again. Willie Mays had all the tools. None surpassed his timing.

by Jason Fry on 18 June 2024 10:50 am I didn’t expect a giddy stretch related to the 2024 Mets, and yet here we are.

I was playing mini-golf and eating ice cream, meaning I was late to my assigned duties (sorry not sorry) and yet was only mildly surprised to find it was Forces of Good 7, Defending But Currently Not So Hot World Champions 0. A David Peterson non-slider immediately made it FoG 7, DbCnsHWC 2 and I felt a smidge of guilt, but no matter; as I excavated the interior of my cup for beaded-up caramel, Brandon Nimmo restored momentum order and it was 9-2.

9-2 on the way to 14-2, with luckless Andrew Knizner pressed into service before the end. The Mets pounded out 22 hits, 17 of them singles, ambushing Jon Gray early and relievers late. (Knizner was unscored upon, because baseball.) Four hits for a suddenly incandescently hot Francisco Lindor (in two-thirds of a night’s work, no less); three for Nimmo, Pete Alonso, Mark Vientos and Francisco Alvarez; two for DJ Stewart including a put-em-on-notice three-run homer in the second; at least one for everyone in the startling lineup save Tyrone Taylor, who somehow missed the memo.

By the end everyone was a little giddy. Gary Cohen was explaining to Keith Hernandez how Mets fans want carnage, not close-game drama; Steve Gelbs was recounting a delightful story about chatting with Max Scherzer and a random kid in the stands; and Scherzer, now in Texas garb, was riding Alonso from the enemy dugout for taking a walk against Knizner. After the game, Gelbs ambushed Nimmo with a query about whether the Mets attribute their winning streak to Grimace throwing out the first pitch last Wednesday. (If you’re not Very Online, it’s a thing.) Nimmo, expecting another round of arglebargle about approach and teamwork and one day at a time, was tickled to be caught off-guard.

Everything’s fun when you’re atop the world, whether you attribute said status to unlikely first pitches, team meetings, sunspots or having sacrificed a pure-white lamb on a blood-soaked obsidian altar beneath the last new moon of spring. (Let’s hope it’s not that last one; sounds kinda mean.)

I’ve watched enough baseball and internalized enough of its maddening ebbs and flows to know not to think too hard about these stretches; it’s simultaneously true that no logic underpins them and that whatever logic is assigned to them anyway can become its own engine of further success. You just enjoy them, knowing from hard experience that the karmic wheel is still turning and so the view from the top is to be savored as long as it lasts.

|

|