The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 20 April 2024 2:42 pm The Mets should consider this a friendly suggestion.

They should also look good in their new uniforms.

This is a test, by the way. We’ve been having a few technical problems and hope to work them out so you can visit our site with ease, link to previous articles and share your thoughts Metwise. Thank you for your patience.

by Jason Fry on 20 April 2024 2:08 am Ah, baseball. It’s a game of redemption, they say. The question sometimes is who gets redeemed last.

Chris Taylor, normally reliable as a Dodger, has endured a nightmarish 2024 so far, one that left him hitting .029 going into Friday night’s game against the Mets. Things didn’t get much better for Taylor in his first AB: In the third he faced Sean Manaea with the Dodgers down 4-0 and trying to get back in the game. Taylor hit into a double play.

But this was a quietly wild game best suited to playing on a seesaw. The Mets beat up Yoshinobu Yamamoto, not long ago the object of their offseason affection, but Yamamoto then harnessed his breaking stuff and was able to keep his team’s powerful lineup at least within striking distance. Manaea was good but inefficient, as Mets starters so often have been, and handed a 4-2 lead to Reed Garrett in the sixth.

Garrett, through not much fault of his own, wound up huddled beneath a caved-in roof. The fault belonged to Joey Wendle, who made a pair of dreadful errors. Garrett persevered and struck out Max Muncy with this bases loaded, which isn’t easy to do, and had a chance to get out of the inning if he could just retire Taylor and his minuscule batting average.

Game of redemption: Taylor spanked a slider that got too much plate into left field and the Dodgers had tied it.

Not ideal, but redemption would have more to say. The Dodgers made an error of their own in the top of the seventh, putting Starling Marte on base ahead of Francisco Lindor. Lindor struggled dreadfully in the beginning of the year, particularly batting from the left side, and hadn’t driven in a runner in scoring position since last season.

Facing Daniel Hudson from the left side, Lindor demolished a 3-2 slider, sending it into the pavilion. The Mets’ lead had been restored and Lindor looked jubilant but also relieved as he embraced Marte after completing his trip around the bases.

This second dose of redemption seemed to deflate the Dodgers a bit; the Mets added two more runs in the eighth and a tack-on run in the ninth, with Jake Diekman finishing up. Old friend Freddie Freeman, who normally salivates at the sight of Mets pitching, struck out three times. That undoubtedly means Freeman will do something terrible to us in the not so distant future, but it won’t be Friday night. That one’s safely in the books.

* * *

The Mets’ City Connect jerseys were unveiled Friday morning, a milestone I approached with a certain dread; this is the organization, after all, that went all in on 1999’s goofy Turn Ahead the Clock promotion and so gave us the Mercury Mets, not to mention birthing the horror that was “Our Team, Our Time.” (Somewhere there’s SNY footage of Greg and me trying to be vaguely diplomatic about the latter.) Since the first wave of City Connects arrived in 2021, I’ve been nervous — to say the least — about what my team would do when its turn came.

Now that we know, I’m in a place I didn’t expect to find myself: underwhelmed. Now that we know, I’m in a place I didn’t expect to find myself: underwhelmed.

Now, let’s get a few things straight.

First off, the Mets got their home and road uniforms right in 1962, and it’s great that they’ve returned to them as their default look in recent years. May it always be so. But I’m not such a rock-ribbed traditionalist that any departure from the standard home and away makes me grind my teeth. I’m fine with alt uniforms, so long as there’s a logic to when they’re presented and so long as the frequency of the alts doesn’t upstage the mains. Weekends can be different; so can weekday matinees and holidays. We can make room for throwbacks and concept uniforms and one-offs and bring back old favorites. I don’t want to see the racing stripes too often (Ron Darling nailed it when he said they look like softball uniforms) but wearing them with ’86 royalty in the house makes complete sense. I’m happy to see the black late-90s unis now and again; I have no use for the blue alts but I can tolerate them on occasion. (Just keep the ice cream hats, the tail and those hideous camo tops locked up — and whoever suggesting pairing camo with pinstriped pants should be kept far away from any and all aesthetic decisions until they draw their final breath.)

Second, I like the City Connects, and I think some of the designs are keepers. The Marlins’ Sugar Kings-inspired alts are far better than their actual uniforms, and they ought to switch posthaste. The Angels should do the same: Their City Connects look like SoCal beachwear, and would give this schizophrenic franchise the visual identity it’s so often lacked. The Padres, Nationals and Rockies had fun with the concept and came up with great results. The Mariners stuck closer to tradition but emerged with a striking reinvention of their look. I like the Giants’ fog uniforms and applaud them for trying something new; the Diamondbacks finally found a color that doesn’t look ridiculous; and who would have thought the Red Sox, of all teams, would try something radical? Granted, the Dodgers look like blueberries (they’re apparently redesigning) and there are a few too many edgy black ensembles, but they can’t all be winners.

The Mets took their City Connect assignment seriously, as their careful attention to the details shows. The design aims to be resonant about New York City while also having fun, weaving in everything from the Queensborough Bridge and subway tokens and going so far as to assemble the pinstripes from the diamond and circle icons that every New Yorker knows means express and local lines. It’s not a complete departure from what we know and love: The lettering is taken from the current road uniforms, and they left the NY alone. And the promotional video is great! (Though live a little, fellas — there’s nothing wrong with pushing your pizza boundaries.)

But it feels like the designers were so focused on the details that they lost the bigger picture. Opting for purple because it’s the color of the 7 line was a fun choice, but look at the new uniform and there’s surprisingly little purple to be seen — it’s most notable as the color of the Nike swoosh. There’s a subway map on the cap liner, but it’s literally invisible. That detail about the diamonds and circles is fun, but you won’t see anything except a black stripe from the stands, or on a big OLED set.

Instead, the uniforms look like asphalt — and before one of the designers puts a hand up, I know that was the inspiration. The problem is that they just look like asphalt. They’re drab, and that’s one thing New York City isn’t. Given how much care went into this project — which, again, I applaud — that’s a strange miss.

by Greg Prince on 18 April 2024 1:52 pm “Don’t you just love it when you come back from the bathroom and find your food waiting for you?” Mia Wallace (Uma Thurman) asks Vincent Vega (John Travolta) over dinner at Jackrabbit Slim’s in Pulp Fiction, just as she has indeed returned from (ahem) powdering her nose to find the “bloody” Durward Kirby Burger she ordered waiting for her. The baseball version of this experience can be just as satisfying.

For very recent example, on Wednesday afternoon, the Mets were leading the Pirates in the bottom of the sixth inning, 2-1. It was a game I was in and out of consuming live, as will happen on a weekday afternoon when I can’t necessarily glue myself to the action. I adore baseball games magically appearing and brightening weekday afternoons, but there tends to be a tradeoff of a few pitches here, a few pitches there, in exchange for the more indulgent aspects of a midweek matinee. In the bottom of the sixth, after Francisco Lindor singled to lead off and advanced to second on a wild pitch while Pete Alonso batted, I had to check out for a few minutes. Maybe more than a few minutes. I didn’t know how many pitches were being thrown nor how the consequences of those pitches were unfolding.

Next time I check in, the first thing I hear on the radio is a discussion between Howie Rose and Keith Raad about the efficacy of a sacrifice bunt in broad terms. Then they drill down to how a specific sacrifice bunt, which might not be approved of as sound strategy in certain circles, sure worked that time. I haven’t yet heard a score, nor exactly the role of the bunt in question on the score, but it seemed to have been laid down by Jeff McNeil, and whatever was going on in the wake of the bunt seemed to be going well for the Mets.

Sure enough, it was Mets 6 Pirates 1, the key hit following the bunt in question coming from Tyrone Taylor, who singled in the previously advanced Lindor and Alonso (who had walked after that wild pitch). Then came the kind of crowning blow that makes every bunt look prescient, Harrison Bader’s two-run homer. I pieced the details together a little later. All I knew at that moment was four runs were delivered to my table during the brief interlude I had stepped away.

Don’t you just love when that happens?

Likewise, don’t you just love realizing your crummy baseball team is now your pretty good baseball team, with each facet of its on-field operation coming around bit by bit until your team is suddenly doing everything fairly well? And isn’t it wonderful when your baseball team has won its most recent contest, 9-1, and it isn’t a shock? The Mets were resolutely crummy for the first five games of this year, no argument. Oh and Five didn’t lie. Yet Oh and Five also didn’t forecast the next thirteen, let alone 157. It was only five games, or so we can tell ourselves now that the Mets have won ten of thirteen and have looked that much more formidable day after day in doing so. I’ve gone from being conditioned to the Mets losing; to surprised at the Mets winning; to, as of the parts of Wednesday’s game I could watch and hear, figuring we have at least a 50-50 chance to come out ahead any day or any night. I may be slow-walking my expectations upward, but after 0-5 to start the year, and 75-87 to ruin last year, I’ll settle for not expecting the worst.

Beating the Pirates on April 17, 2024, was also good long-term payback for losing to the Pirates on April 17, 1964, each game having been played in Flushing, the earlier one having been the first the Mets ever hosted in the borough of Queens. Presumably by coincidence, MLB sent Pittsburgh back to New York on the 60th anniversary of the opening of Shea Stadium. Good for the Mets for picking up on the milestone and inviting home their starting pitcher from that inaugural game, Jack Fisher, to toss out a ceremonial first pitch, accompanied by that year’s Met among Mets, 1964 National League All-Star starting second baseman Ron Hunt. The Immortal Chris Majkowski (I believe that’s his full name) also deserves applause for sharing with WCBS listeners during Wednesday’s game Bob Murphy’s call of Fisher’s very first pitch.

It sounded like this:

And the leadoff batter in the ballgame is Dick Schofield, switch-hitting shortstop of the Pirates, and ladies and gentlemen, we’re ready to go.

You can imagine there must be a lump in the throat of twenty-five year-old Jack Fisher, the Frostburg, Maryland native as he looks in the for the first sign ever taken in the twenty-five million dollar ballpark named Shea Stadium.

This is it.

Jack Fisher is into his windup and here’s the first pitch ever…a strike on the outside corner.

The roar comes up as the first pitch ever thrown in this beautiful baseball palace is over. Perhaps the tension now is broken, and the game is underway.

Jesse Gonder walking slowly, back toward the mound. Out in the outfield, the outfielders are checking their sunglasses; the breeze not really too much of a factor in the game, kind of blowing diagonally from right across toward left.

Three hundred and forty one feet down the foul lines to the wall. The ballpark is symmetrical. Three fifty-eight in left center and right center.

Maj didn’t play all of that on Wednesday, because the pitch clock tyrannically moves today’s games along too briskly to allow announcers to paint the most fulsome word pictures they can. It’s Amazin’ to consider Murph once had to explain what Shea Stadium looked like to everybody tuning in, because nobody had yet seen it. Now we see it in only in our memories or photographs or footage, or, perhaps best of all, when we’re treated to Bob Murphy’s voice in our head.

We, meaning Mets fans in general, had seen the Mets beat the Pirates by a score of 9-1 before Wednesday. The first time Mets 9 Pirates 1 was a final was the first time anybody saw the Mets beat anybody by any score. The Mets were 0-9 heading into Forbes Field on April 23, 1962 — 0-9 on the year, 0-9 in their existence. Just as Oh and Five didn’t foretell everything about the weeks ahead in 2024, the 1962 Mets were going to win a game sooner or later. Sooner arrived in Pittsburgh when Jay Hook went the distance to lift the Mets into the win column at least once (and then answered so many questions from the press afterwards that he discovered the shower in the visiting clubhouse had run out of hot water).

I was kind of hoping to find out that the 60th anniversary of the first game at Shea marked the first time the Mets had beaten the Pirates, 9-1, since their first-ever win. I looked it up via Baseball Reference’s Stathead tool and learned, nope, this was the fourth Mets 9 Pirates 1 tally in the rivalry’s history. I was at one of the two others, on September 14, 2010, an R.A. Dickey special whose deep-dive details apparently hadn’t stuck indelibly to my consciousness. The other came at Three Rivers, on September 8, 1982, which rang an audible bell for me datewise. It was the finale of a series that began two nights earlier with the Pirates honoring their retiring captain and legend Willie Stargell. Willie Stargell capped Willie Stargell Night on September 6, 1982, by pinch-hitting and singling off freshly called up Doug Sisk.

Stargell was uncommonly capable of doing more damage than that versus the Mets. Nobody to this day has hit more home runs off Met pitching than Willie Stargell. Pops clobbered 60. The third of those longballs came on April 17, 1964: the first home run anybody ever hit at Shea Stadium, part of a 4-for-5 christening of the new ballpark. Willie then took it easier on us for the rest of that opening series, though one of his teammates kept up the slugging. The second-ever homer at Shea came the next day, off the bat of Pirate first baseman Donn Clendenon, almost precisely five-and-a-half years before he would accept World Series MVP honors at Shea Stadium for the Mets. The third-ever Shea Stadium home run, and first (at last!) struck by a member of the home team, came in the next series the Mets played, against the Cubs. It was hit by Wednesday’s Citi Field co-guest of honor Hunt.

A lot of what goes around can come around if you pay attention, regardless that you sometimes have to miss a few pitches.

You don’t have to miss the latest episode of National League Town. It’s right here.

by Jason Fry on 17 April 2024 1:22 am How do you know things are going well? Here’s a sign: You take the lead off an opposing pitcher before he even throws a pitch.

The Mets somehow did that Tuesday night, the culmination of several unlikely events. They were down 1-0 to the Pirates in the seventh after being smothered by Pittsburgh’s Jared Jones and watching that lone Pirate run come home on an excuse-me bleeder off the bat of Bryan Reynolds, the kind of evening that makes you think this time the deck is too stacked for you to find your way to safety. But with one out in the seventh Francisco Lindor walked and Pete Alonso singled him to third. Brett Baty should have been next up, but he’d recently exited with a tweaked hamstring. (Baty is … wait for it … day to day.) Instead of Baty, we got the so far relatively unassuming Joey Wendle — who of course spanked a double into the left-field corner off Luis Ortiz to tie the game. Francisco Alvarez flied out, the second time in the game he’d stranded a gimme run at third, and Jose Hernandez relieved Ortiz.

From my vantage point up in 423, what happened next was … well, it was confusing. There were umpires running around and Jeff McNeil was conversing intensely with Henry Davis and then Alonso was happily trotting home and Hernandez hadn’t thrown a pitch yet the Mets had taken the lead. OK then! When Hernandez finally did get to actually pitch things didn’t go much better: McNeil served a ball into short left that fell in and gave the Mets an insurance run, and eventually a 3-1 win.

There was more to it than that, starting with my late afternoon decision that I ought to go to the game, because it was a warm spring night and going to the game is what I do, or at least what I used to do — a mournful realization but one I decided had an easy remedy. I secured a pretty good StubHub ticket for a whopping $13.61 (that’s with fees), got to Citi Field early and amused myself strolling around before finding my way to my seat, where I was soon happy Emily wasn’t with me.

I better explain that last part: If I determine someone within earshot is a baseball ignoramus or otherwise detracting from my evening, I calibrate my ears accordingly and essentially erase them from my audio experience. (Yes, it’s a gift.) My wife, on the the other hand, has what baseball players call rabbit ears as well as an unfortunate ability to attract dummies like a magnet. The guy mansplaining while getting basic facts wrong? The shrieking child on Day 1,724 of not being told no? The leather lung confidently calling balls and strikes from an oblique angle in the Promenade? In a typical game you’ll find at least one and possibly all three of them directly behind Emily; it’s usually around the fourth inning that she boils over and I (who’ve noticed nothing due to the aforementioned calibration) am soon thanking God she isn’t armed.

Now, a bunch of my neighbors for Tuesday night were actually Mets fans, and none of them were bad people — one Dad was even diligent about keeping hyperactive kids in their seats and out of the sightlines of those behind them, a rare courtesy these days. But the kids were part of a birthday party which inevitably turned distracted and sugar-addled, behind the kids was an assemblage of vaguely Goth kids whose primary interest seemed to be vaping, behind me were two girls yammering away in rapid-fire French … entire innings passed during which I was pretty sure I was the only person in the section watching the game, and it was taking considerable effort to not get swept away by the aggressive non-game-watching surrounding me. If my wife had been there I might be dictating this to Greg from jail.

Oh, and I was also getting cold — two unseasonably warm April afternoons lulled me into forgetting that a night game before May isn’t to be taken lightly. How soon we forget!

Between the yammering and the shivering I was beginning to think the night would go down as a cautionary tale, with baseball part of the lesson: Jose Quintana was annoyingly inefficient and I kept waiting for the roof to cave in on him as it eventually had on Adrian Houser. That didn’t really happen, in part because for a second night the Pirates kept getting in their own way. A Connor Joe baserunning blunder short-circuited their first inning, they inexplicably played the infield in against Alvarez with the score 0-0, and they pulled Jones after five innings.

It turned out after the game that was the plan, and Jones even expressed appreciation for the kid gloves, and while I roll my eyes at Once Pitchers Were Manly Men nonsense, I have to admit reading that made me feel 10,000 years old. Jones was unhittable and fearless: He threw 59 pitches and 50 of them were strikes, for Christ’s sake! He was clearly better than anyone else the Pirates could have put out there, as Ortiz and Hernandez soon demonstrated. And yet 59 pitches and a 1-0 lead was enough, somehow. The Pirates arrived at Citi Field as an early-season success story, and I’m happy for their long-suffering fans, but they’ve spent the last two nights taking aim at their own feet.

The Mets, on the other hand, keep scratching and clawing and doing enough things right so that they could fall into a little luck. Reed Garrett recorded all six of his outs via Ks, Jorge Lopez navigated a spotless eighth and Drew Smith looked as good as I can recall seeing him, filling in for Edwin Diaz as closer. They got some nifty defense from Alonso and Baty and Harrison Bader. And of course they took the lead without a pitch being thrown. It was a night for getting reacquainted with old habits, but that was a new one.

by Jason Fry on 15 April 2024 11:40 pm The Mets are suddenly good.

Well, not good exactly. Statistically speaking, they’re average. But in the vibes column — which you won’t find in your paper, on MLB.com or Baseball Reference, so don’t look for it — the Mets are killing it.

They rose to average statistically and red hot vibe-istically by beating the Pirates in an odd affair on Jackie Robinson Night, with both Mets and Bucs wearing blue 42s on their backs and their meeting blessed by the regal presence of Rachel Robinson, now 101. She, of course, was very much a partner in Jackie Robinson’s drama, which is somehow both long ago and ever-present given how much his work remains unfinished; seeing her greeted pregame by the likes of Pete Alonso, Francisco Lindor and Brandon Nimmo gave me that same chill that a rich baseball connection always inspires.

By the way, I was Shea in April 1997 on the night MLB announced mid-game that 42 was being retired, up in the upper deck watching Bud Selig, Rachel Robinson and President Clinton. It’s the coldest I’ve ever been at a baseball game, if you don’t count one May afternoon in Candlestick Park. I remember three pretty random facts: being so cold that my misery ebbed into a worrisome “To Build a Fire” lethargy; that Selig mentioned Butch Huskey would get to keep wearing 42 and that I was pretty sure that was the only time Bud Selig had ever said or would ever say Butch Huskey’s name; and that Toby Borland did his best work as a Met that night, much to the relief of all of us turning into freeze-dried corpses up in the tundralike red seats.

It was just a little warmer Monday night, in the high 60s after a sparkling spring day that had seen the mercury approach 80. The Mets and Pirates picked up where the Mets and Royals had left off, with neither team able to push across a run. Which was statistically similar to what Jose Butto and Cole Ragans had done on Dwight Gooden‘s special day, except Butto’s great stuff had been obvious and I had no idea how Adrian Houser was surviving: He kept walking guys and leaving pitches in the middle of the plate, which were somehow missed by increasingly exasperated Pirates.

Houser’s luck ran out, as one had figured it would, in the sixth: Andrew McCutchen got a second lease on life when home-plate ump Edwin Moscoso called a sinker that caught the bottom of the strike zone a ball. (Hey you: foreshadowing.) Two pitches later Houser left a sinker in the middle of the plate and this time his largesse was accepted: McCutchen spanked it through the infield to give the Pirates a 1-0 lead and end Houser’s night. Drew Smith came on and was lousy, pushing Pittsburgh’s lead up to 3-0, and Citi Field had become a sea of mutterings.

But the Mets equalized things in a hurry in the bottom of the inning, scoring three runs of their own in rapid succession on a Francisco Alvarez bases-loaded walk, a Jeff McNeil sac fly enabled by Connor Joe inexplicably spiking the ball into the turf, and a DJ Stewart pinch-hit double scorched over Joe’s head. The Mets got exemplary work from Brooks Raley and Adam Ottavino, whose slider/sweeper has never looked sharper than it has the last two nights, and then the Pirates imploded.

2024 has been good to Pittsburgh so far, but the eighth inning was the stuff of nightmares, one of those games you find yourself fuming about at 3 am weeks later. Aroldis Chapman got Alvarez looking at a third strike, but the putaway came three pitches after Moscoso clearly missed a previous third strike. That left Chapman clearly in a state of at least moderate agitation. He struck out McNeil on a slider in the dirt, but it eluded Henry Davis and so got McNeil to first. Stewart walked, with three of the balls granted extremely close, and now Chapman had gone from simmering to roiling. McNeil and Stewart pulled off a double steal and Harrison Bader ripped a double down the left-field line to give the Mets a two-run lead and earn Chapman a shower after jawing with Moscoso for his previous sins.

The Pirates weren’t done with their pratfalls: Bader stole third off Roansy Contreras basically uncontested, and after the Pirates belatedly brought the infield in, he streaked for home on a bounder by Nimmo to the second baseman. The ball went all of 110 feet but Bader slipped beneath Davis’s tag, popped up with the sixth run and swaggered into the dugout — not quite Trea Turner‘s Fred Astaire move through the plate on the cool factor scale, but pretty close. Bader looks healthy for the first time in years, he’s mashing lefties, and he slathers any play he’s involved in with a little mustard. And I’m starting to love him, for those reasons as well as for his marvelous Lindoresque pink batting gloves, his giddy dugout yammering in the direction of anyone who might be listening, and the mean center field he plays.

Edwin Diaz came in, and truth be told he once again didn’t look quite himself, which might be a thing to watch. But it was the lone blemish on a night that started as celebratory but solemn and ended in gleeful abandon. The Mets are .500, but their vibes differential suggests a better record than that. Which is a bit of advanced stats I can get behind.

by Greg Prince on 15 April 2024 12:36 pm I wish I had brought some string with me. An enormous spool of string. Had I, I could have offered some to each player I saw in the Shannon Forde Press Conference Room Sunday morning and asked him to align himself just so in order to form the most Amazin’ live-action Immaculate Grid you could ever hope to see.

Mike Torrez of the Mets in 1983 and 1984, you also played for the Cardinals and the Expos and the A’s and the Orioles and the Red Sox and the Yankees. Please stand in the upper left.

Gary Sheffield of the 2009 Mets, you came up with the Brewers and preceded to touch down with the Padres, Marlins, Dodgers, Braves, Yankees and Tigers. Would you mind heading over to middle-right?

Barry Lyons, whose Met service spanned 1986 to 1990, I know you have some Dodgers, Angels and White Sox on your ledger. You’d go great in the bottom row, thanks.

Mookie Wilson was a Blue Jay; Roger McDowell a Phillie, a Dodger, a Ranger and an Oriole; Rafael Santana a Cardinal, a Yankee and an Indian. If I needed a Met who was a Pirate, I had Lee Mazzilli. A Met who was a Twin? There’s Tim Teufel. Met-Rockie or Met-Cub? I could use Howard Johnson. Would Sandy Carter mind standing in for her husband Gary if a Met-Giant was necessary? Wait, I could use Darryl Strawberry there. And I could use Jesse Orosco practically anywhere.

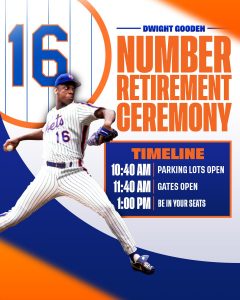

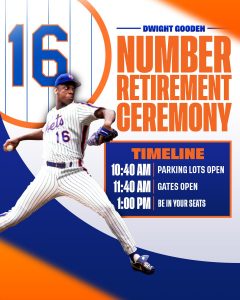

I could have done this all day, but putting baseball players in a box was not why I was there or they were there. This was about a round icon for a true icon, a circle with a 16 in the middle of it, and teammates who were happy to revolve around the man who it represents.

This was number-retirement day for Dwight Gooden, better known as Doc, only known as Doc, based on how he was addressed and referred to. That’s how it is with teammates, fans and onlookers who like to think they know what’s what. I was in the latter category most of Sunday, a media member by my credential, though a fan through and through. There’s Doc! There’s Straw! There’s Mazz and HoJo and, yeah, that’s Sheff! It’s hard to believe people bother with given names in real life.

There’s Straw! There’s Doc! Doc was real life for us from 1984 to 1994, as unreal as he could be on the mound for the first phase of that tenure. He hadn’t thrown a pitch for the Mets in thirty years as of Sunday. He’d been waiting for Sunday for thirty years as of Sunday, not so much to be the center of attention, but, as he said in the morning, to “make it right” between himself and the fans.

I think he did right by us.

Later he would stand stand amid an ill-timed shower in short center field, ignoring the gusts and speaking through the irony of how a little rain must fall on all our lives, even those who seem to have the world in their right hand. He reminded everybody who saw fit to celebrate with him that he couldn’t have done what he did without us cheering him at his best and sticking with him through everything else.

“I’m a Met, I’m a Met,” he said, a fact so nice it deserved to be mentioned twice.

Of course Doc had to clarify on that count since he also mentioned another association he had with another ballclub in town (twice), which isn’t necessarily a dealbreaker in the aftermath of anybody’s career. Torrez, Santana, Mazzilli, Sheffield, Strawberry, even the current manager Carlos Mendoza and a few of his charges…we’ll look past past identities if you come around here some more. At any rate, it wasn’t a day for recriminations, even if this day should have happened sooner than thirty years after the Mets and Doc initially “cut ties,” to use his phrase. He shared with the fans a story I’ve heard him tell in other settings, that he tried to come back to Shea as a pitcher when he thought he still had a little something left, but management rebuffed him. It was the late 1990s and the very early 2000s when he asked, twice. The Mets were doing well enough that it was a reasonable enough business decision that maybe a reunion didn’t make pitching sense. It also wasn’t that far removed from the time “business” reasons may have left a cloud over the Doc-Mets relationship.

The part that kills you is the Mets declining to do the one-day contract bit he’d requested when he was done, a ceremonial signing that would have allowed the pitcher who embodied them at their 1980s best to “retire as a Met” and get the new century off on the right foot. Teams and players of note make that kind of arrangement every now and then. It’s always a feelgood moment for all involved, a reminder that contracts and transactions are secondary to who you feel you are and how you wish to be remembered. Dwight Gooden pitched for the Yankees, the Indians, the Astros, the Devil Rays and the Yankees again. He was a Met “always,” he said. How about a gesture to make that clear to all concerned?

The Mets told him no, they weren’t going to do that. Fast-forward nearly a quarter-century and you could almost hear a mobile device ringing, and the reply when it was answered:

“New management, who dis?”

It was Steve Cohen on the line, telling Doc that No. 16 would be going up in the space Doc reserved for it back when Citi Field was Shea Stadium’s parking lot. Thus, Doc was back where he always belonged, give or take a stadium footprint. So was lots of his family, his nephew Gary Sheffield among them, along with lots of his teammates. The guys from the press conference room were on the field with him, as were Keith Hernandez and Ron Darling, who work there. Strawberry had a heart attack during Spring Training. His making it back really told you what this day meant to everybody who played with Doc.

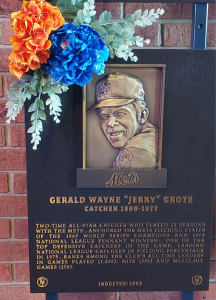

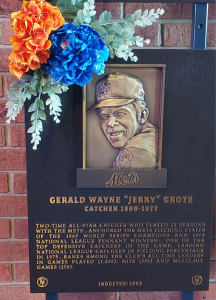

There’s everybody! Some of these Mets from the Eighties you’re used to seeing congregating in Flushing; other than Torrez, who Doc credits with mentoring him through his first months in the majors, nobody was a complete stranger to contemporary Met environs. Yet it’s breathtaking to realize they’re right in front of you as a group. Above the stairs of the Jackie Robinson Rotunda, where the Mets Hall of Fame now lives and breathes among the fans (not to be confused with the relocated Mets Museum, which now sits in an unused wardrobe closet somewhere on the edge of Northern Blvd.), orange and blue flowers adorned the plaques of Buddy Harrelson and Jerry Grote. Buddy died in January, Jerry just over a week ago. You used to see those guys and their 1969 teammates plenty at Shea and sometimes at Citi. Only a relative few are available to visit in 2024. What I’m saying is that when World Champion Mets are around you, open your eyes and your ears and, if you’re lucky enough to be issued an official tag of some sort, your notebook.

During the press conference, where most of the players beamed proudly as they sat against a side wall (and Jay Horwitz went into PR guy mode clearing a little space between encroaching photographers and Darryl and Doc enjoying a brief chat), I asked the guest of honor what it meant to know his 16 was about to be installed next door to 24 and down the block from 41. All the Mets who have numbers retired are franchise royalty, but Willie Mays and Tom Seaver — that’s baseball stratosphere. Doc picked up on my implication, told us Tom was “a friend of mine” and that he got to know Willie “a little bit,” too, but to him, an honor like this is “for all of us”. For Keith. For Ron. For Darryl. For everybody on that wall over there, especially for the 1986 crew, including the 1986 Met who is no longer with us. Or as I overheard Sandy Carter say later, “I know Gary’s with us in spirit.”

A couple of catchers were with us in spirit. After Doc moved on to other pre-festivities obligations, media was invited to spend time with Doc’s teammates, most of whom helpfully hung around to be pestered by the likes of me. As baseball’s particular attention to uniform numbers provided the excuse for us to have been here in the first place, I sought out Rafael Santana and asked “Raffy” (it seemed the thing to call him) about his relationship with Buddy, the man who coached him and shared 3 with him. Raffy told me Buddy was not only a great help to him but that when Raffy asked if he could give 3 back to him — Harrelson had been managing in the minors when he was installed as a lieutenant of Davey Johnson’s — Buddy told him, no, it’s more important that you have your number now, and the third base coach was fine wearing 23 in ’85 and ’86. Raffy affirmed it was meaningful to him to be in the exclusive club of two, Harrelson and Santana, who could say they were the shortstops on the diamond when the Mets became world champions.

Offering numbers to those who used to have them was a resonant subject. Doc asked Mazz, upon his return from Pittsburgh in 1986, if he wanted 16 back. Mazzilli was a big deal as 16 in Queens pre-Gooden, but Lee demurred, telling Doc it was his now. For that matter, none other than Whitey Ford let Doc know in 1996 that if he wished to wear 16 with his new club, he’d OK the Yankees unretiring it for him. That’s how big a deal Doc had always been in New York (and how much of a mensch Whitey Ford was). Doc couldn’t say yes to that.

“Respect for those people who came before you” was a theme that surfaced when I asked “Rog” McDowell about the number he wore, which, as I pointed out to him, we’d be seeing plenty the next day, Monday, April 15. Jackie Robinson Day was coming and every Met and every player in the major leagues would wear 42. I told him that every year on this occasion Mets fans like me couldn’t help but think of him, of Butch Huskey, of Ron Taylor, of the late Ron Hodges. McDowell definitely appreciated the connection, and it didn’t take Bud Selig’s declaration that 42 would be retired for everybody everywhere in 1997. Sure, he wore 42 simply because it was the number “Charlie Samuels gave me,” but he understood whose it was long before he and Doc were drafted together to be Mets in 1982.

Roger explained his father instilled in him that respect for those who preceded him, and that Mel Allen taught him history lessons on This Week in Baseball. The show and the homegrown curiosity sent young Rog to the local library to check out books on Jackie Robinson (and Ted Williams, Tom Seaver, Carl Yastrzemski and Babe Ruth as well) to learn all he could about the endeavor he would someday enter. He knew about Jackie at UCLA. He knew about Jackie in the military. Fans, he says, sometimes ask him to adorn his autograph with his number. Roger told me he’s “hesitant” to do so. It’s Jackie Robinson’s number.

I didn’t get a chance to ask Mookie Wilson anything, but I did hear him say that thing that all retired ballplayers seem to say when they talk about getting together with old teammates: “the lies get bigger” as the years go by. It’s always said with a chuckle, much as the observation of veteran players that younger players don’t sit around and talk about the game like we used to do is inevitably uttered with an undercurrent of scorn. No scorn on Sunday, though. Doc appeared happy and incredibly relaxed. Happy is understandable. Relaxed was a little surprising. Doc never wasn’t courteous to the press or anybody in a public setting, but the kid who was dealing with an army of microphones and cameras from age 19 on endured the attention in his youth as if he wished he could squirm away from it all. We know from the detours his life took that it probably wasn’t the ideal way for a young man to transition into full adulthood. On the cusp of 60, maybe it shouldn’t be surprising that Doc Gooden showed up Sunday as the old pro, as polished as a Seaver or a Mays in elder statesmanship, but we still reflexively think of him as being 20 winning 20. He seems to be winning his days nowadays. Those are the victories that count most going forward.

After the ceremonies and a 46-minute rain delay, the sun came out and the Mets won a game that you figure can’t but help them going forward.

It certainly couldn’t hurt.

You couldn’t miss Jose Butto paying proper homage to Dr. K with no runs and nine strikeouts in six innings.

You would have preferred KC’s Cole Ragans didn’t nearly match him by fanning eight and allowing nothing of consequence in six and therefore keeping the scoreboard a little too immaculate.

You were grateful to recently dormant Adam Ottavino and Brooks Raley for keeping Royals bats waving at air (2 Ks each in an inning apiece).

You were delighted that Francisco Lindor, in his long-term bid to join Buddy and Raffy as Met shortstops who will one day reunite with his world champion teammates, processed the standing-ovation encouragement the crowds are giving him into a couple of base hits.

You were relieved, despite lingering distaste for Kansas City’s misdeeds in New York in the fall of 2015, that the last of those world champion Royals still on these Royals, Salvador Perez, was able to stand up after a slam-bam play at the plate, even if the venerable backstop had to exit the action.

You were, if you were of my vintage, very much into hearing hits from the ’80s on the PA all day, a perfect accompaniment to a day devoted to a pitcher who prevented hits in the ’80s.

You were, if you were stoically pro-Mets while behaving yourself in the press box, quietly ecstatic that an eighth-inning rally built mainly on walks and punctuated by ex-Yankee Harrison Bader’s infield squib turned into two Met runs, literally enough of a cushion for trumpets to blare and Edwin Diaz to convert a save opportunity.

You weren’t really worried when Diaz gave up a solo home run with two outs. Really you weren’t. Edwin got the last out and we had a 2-1 Mets triumph over the Royals that was the only fitting way to cap off a day such as this. It didn’t alter the result of the 2015 World Series, nor did it instigate a cosmic do-over that would have had Doc facing Bret Saberhagen in Games One, Four and possibly Seven of the 1985 World Series, but we got a win on the field and a 16 in the rafters.

When you get a day like this, its rarity score is off the charts.

by Greg Prince on 14 April 2024 6:27 am Sometimes you stumble into something that catapults you toward something else. Shortly before the Mets, amid Sean Manaea’s off afternoon and a surfeit of Bobby Witt, stumbled Saturday into their 11-7 loss to the Royals, I stumbled into a nugget of information totally new to me. Sixty years ago, on April 13, 1964, the Mets held a season’s eve workout, itself nothing unusual. The club was about to travel to Philadelphia to begin its third year of existence, so they figured they’d get the last of their Spring Training in at home.

Except home wasn’t ready. Shea Stadium would open on April 17, and those who were finishing it up needed every last minute to put every detail in place. Hence, the Mets held their workout at Hofstra University in Hempstead. Hofstra! The same Hofstra a few Meadowbrook Parkway exits from where I grew up, the same Hofstra literally down the block from the home of the Nets (1972-1977), the same Hofstra that served as summer camp and base of operations for the Jets (1968-2008). But the Mets? As far as I knew until this weekend, Hofstra held only two connections to the Mets.

1) My friend Dana Brand, who defined what it meant to be a Mets Fan, taught American Literature there.

2) Dana organized an academic conference devoted to the Mets that coincided with their 50th anniversary in 2012, one year after Dana died without warning. That wonderful event had Dana’s imprint all over it.

Now, I had a third reason to connect Hofstra and the Mets: the 1964 workout that, according to Newsday, had the same effect on the neighborhood’s baseball fans that the Beatles showing up in Manhattan had on the musically inclined two months earlier.

“The scene at Hofstra — where a crowd of about 1,500, mostly small boys, turned up — was one of joyful pandemonium,” Joe Donnelly reported. “With no fences along the foul lines, it was every Met for himself against three-dozen or so boys who came equipped with gloves and engaged their idols in glove-to-glove war for every loose ball.” “The scene at Hofstra — where a crowd of about 1,500, mostly small boys, turned up — was one of joyful pandemonium,” Joe Donnelly reported. “With no fences along the foul lines, it was every Met for himself against three-dozen or so boys who came equipped with gloves and engaged their idols in glove-to-glove war for every loose ball.”

It’s not that the Mets didn’t want to be generous. It’s that the Mets brought all of sixty baseballs to practice with and, well, they were gonna run out before every player could take his swings. The Mets’ paucity was the fans’ potential bounty. Aching for a foul ball from the stands was one thing, but this was the horsehide equivalent of scheming for a few locks of hair off the heads of the Lads from Liverpool and magically being granted a barber’s license.

“They’d knock you down for a ball,” 19-year-old Ed Kranepool told Donnelly. “They’re friendly enough — but they want souvenirs.” The Mets responded, per Donnelly, by playing some of their most diligent defense to date. “As the supply of baseballs dwindled,” he wrote, “certain Mets, who wanted another batting practice turn, gave their greatest fielding exhibitions as they hustled to retain baseballs.”

Desired keepsakes included the players’ caps or maybe the players themselves, for once BP could be extended no further, the “friendly enough” kids chased the Mets, presumably out of adoration, to their temporary clubhouse beyond left field so they could shower, dress and prepare for the season ahead in one piece. Coach Wes Westrum, who caught for the Giants when the Giants belonged to New York, compared the scene that ensued at day’s end to the jubilant hordes at the Polo Grounds who poured onto the field when Bobby Thomson launched his Shot Heard ’Round the World in 1951, “only there were many more cops to hold the fans back that day.”

Duke Snider, who was about to have his wish to move to a contender granted with the sale of his contract to San Francisco, summed it up:

“This was a typical Met afternoon.”

Let us hope a couple of difficult but not impossible fly balls that couldn’t be caught — one clanking off the glove of Starling Marte for three bases, another barely out of the grasp of Brandon Nimmo en route to it becoming a home run for Salvador Perez — doesn’t represent a typical Met afternoon nowadays. If Saturday’s matinee was, save for Pete Alonso going deep twice, atypical, Sunday’s finale versus Kansas City looms as extraordinary for what will precede it.

On Sunday, the Mets are retiring 16 for Dwight Gooden. The last time the Mets retired a uniform number on a Sunday afternoon, it was 1988, the number was 41, and its bearer was Tom Seaver. The vagaries of scheduling presumably accounts for Doc’s honor landing on the same day of the week as Tom’s, but it sure seems appropriate. In the annals of Met acedom, there’s Tom, then Doc. On Sunday, the Mets are retiring 16 for Dwight Gooden. The last time the Mets retired a uniform number on a Sunday afternoon, it was 1988, the number was 41, and its bearer was Tom Seaver. The vagaries of scheduling presumably accounts for Doc’s honor landing on the same day of the week as Tom’s, but it sure seems appropriate. In the annals of Met acedom, there’s Tom, then Doc.

The Mets retired 41 the season after Seaver brushed the last of the dirt from his right knee and hung up his glove for good. They waited nearly a quarter-century after Gooden’s final professional pitch to hoist 16 to the rafters. The organization used to be slow about these things if your name wasn’t Tom Seaver. The organization was also slow to recover from the time it stumbled mightily and traded Tom Seaver. That happened in 1977. The Mets weren’t remotely the same again until Dwight Gooden came along in 1984, throwing fast and going places faster. “There’s Tom, then Doc” worked as an irrefutable Metsian construct by 1985.

But let’s not be too harsh on the subject of stumbling. Stumbling into that Mets-at-Hofstra interlude indeed catapulted me into something else. Once I had Hofstra and Dana Brand on the brain, I picked up Dana’s first book to read how he framed the arrival of Dwight Gooden onto the Mets’ heretofore arid landscape and the explosion of Dwight Gooden into our everlasting consciousness. Professor Brand’s interpretations were and are consistently delightful and reliably insightful.

Dana quoted an array of statistics from 1984 and 1985 that translate as enormous now as they were to experience then, before concluding that, while baseball isn’t only “about numbers,” sometimes “the only language we have” for expressing “the sublime, the beautiful terror of magnitude” of output like Doc’s “is numbers”.

One of the greatest pleasures I have had as a Mets fan was seeing Gooden when he was 19 and 20. I remember the games behind these numbers. I remember him striking out the side in his first All-Star game appearance. I remember him striking out 16 batters in two consecutive games. I remember how perfectly unhittable he was. I remember how excited I was. I remember what it felt like as these unprecedented numbers assumed their permanent form. I savored them, I thought of them over and over. I couldn’t believe that I was alive to see this. I couldn’t believe that this was being done by a Met.

Me from 1985 couldn’t believe it, either. Me from 1986 through 1994 never believed the same Doc wasn’t still pitching for the Mets. Of course he was. A little less spectacular as the years went by, a little worn down by time and travails, but still Doc. Then one day he wasn’t a Met, and 16, so indelibly associated with one player and one phenomenon, eventually landed on the jerseys of those who were Mets. If Dwight Gooden wasn’t going to wear it, somebody had to, it was supposed. A few times it was issued to players (Derek Bell, David Cone during his brief comeback, Rick Ankiel), who wished to pay homage to the No. 16 who used to strike out 16 at a clip. A few other times, a player would show up who could claim his own history with the digits (Hideo Nomo, Doug Minetkiewicz, Paul Lo Duca) and have his personal preferences deferred to. But after a while, it became just another number that got issued to commonfolk just passing through (Rob Johnson, Danny Muno, Kevin Kaczmarski). Pinch-runner deluxe Travis Jankowski was the most recent Met to wear 16, in 2022.

Last August, the Mets announced their institutional amnesia had been cured. Me from 1985 couldn’t believe how common 16 had become. Me in 2023 was a mixture of relieved and elated when it was announced 16 would no longer be thrown into the uniform lottery every February. It deserved better. He deserved better.

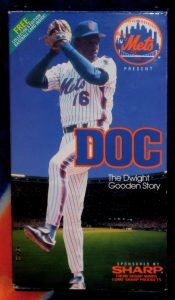

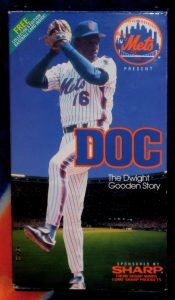

If we frame what Dwight Gooden did as a Met in Hollywood terms, Doc was the major studio release that proved a summertime blockbuster, completely exceeding the most optimistic of industry forecasts. They then made a sequel, and Doc II did even better, shattering box office records, drawing critical raves and winning every major award. Doc loomed as a lucrative franchise.

So they kept making sequels. Doc III, which opened to massive expectations in 1986, did all right by most standards, but fell short of what diehards were anticipating. Doc IV had problems in production, let’s say, and didn’t hit screens until June 1987. It did OK, but nobody embraced the turn the main character had taken. The controversial climactic scene of 1988’s Doc V detracted from what had been a good, solid popcorn flick; you wish they could fiddle with CGI and release a Scioscialess cut. A loyal following ensured there’d continue to be an audience for Doc content, though by the mid-1990s, everything this studio was putting out carried a straight-to-video stigma. So they kept making sequels. Doc III, which opened to massive expectations in 1986, did all right by most standards, but fell short of what diehards were anticipating. Doc IV had problems in production, let’s say, and didn’t hit screens until June 1987. It did OK, but nobody embraced the turn the main character had taken. The controversial climactic scene of 1988’s Doc V detracted from what had been a good, solid popcorn flick; you wish they could fiddle with CGI and release a Scioscialess cut. A loyal following ensured there’d continue to be an audience for Doc content, though by the mid-1990s, everything this studio was putting out carried a straight-to-video stigma.

Nobody much worries that the latter versions of Jaws didn’t live up to the original. I understand if you get on a tram at Universal Studios, you’ll still be exposed to a mechanical shark. Whatever isn’t beloved about The Godfather Part III doesn’t keep anybody from quoting the first two films with reverence. Rocky V…you get the picture. Sometimes there may be every business reason to keep churning out sequels, even if they don’t hold up as well as what preceded and inspired them.

Thing is, Dwight Gooden wasn’t only 1984 and 1985. The nine-season coda to the two-season tour de force that made him a legend was still the stuff of upper-level mortals. Doc won 157 games for the Mets, more than anybody else not named Tom Seaver. He didn’t win them all at once. It only feels like he did because what he did out of the box overwhelms whatever else was packed into his Met career. He pitched spectacularly for a couple of years. He pitched well for long time.

The Doc who will be at the ceremonial center of Sunday started 303 regular-season games for the Mets, which means some other pitcher started against him 303 times. Pitchers talk about facing opposing lineups, but we as fans love to dive into pitchers versus pitchers — mound opponents, mound duels. When we think about pitchers going up against each other, the fellows with the bats seem almost incidental. Given the magnitude 16 is about to take on, I rifled through Gooden’s game logs on Baseball Reference in search of one statistic in particular:

How often did Doc go up against a starting pitcher who went on to have his number retired?

As we’ve seen by the way the Mets have gone about it, number retirement is more art than science, and more impressionism than any other art form. There are no leaguewide regulations governing who may be deemed worthy. Every franchise has its own reasons for bestowing or not bestowing its own ultimate in-universe honor upon a given player, until the rules are bent or rewritten or cast aside, because some things you just know in your gut are the right things to do.

Doc faced off against a lot of really good pitchers in his Met tenure, pitchers I could imagine having their numbers retired under the right circumstances. Some of Gooden’s most distinguished mound opponents earned praise and accolades and took home serious hardware at their peak, but it didn’t usher them onto whatever wall or rafter a team for whom they excelled uses to display its most indelible mark of distinction. Free agency may have been a boon to players, but it’s also meant less sticking around long enough to cement the kind of bond that leads to a team retiring a number.

You know who were outstanding pitchers active at some point in the National League between 1984 and 1994? To name a few, there were Joaquin Andujar; John Tudor; Doug Drabek; Charlie Hough; Rick Reuschel; Mario Soto; Rick Sutcliffe; Dennis Martinez; Tom Browning; Orel Hershiser; Vida Blue. None of them has a number retired by a major league franchise. It doesn’t make any of their careers less excellent in retrospect. At their best, each of them was a tough son of a gun, and I know I never relished the prospect of Mets batters facing any of them.

Dwight Gooden pitched against each of them, however, and I would take Dwight Gooden over every single of one of them, just as I took Dwight Gooden over every single of them when he faced every single one of them. Until we knew 16 would be looking down from the left field corner of Citi Field, those guys qualified as the de facto peers of Dwight Gooden. Really and truly good, just not considered among the very, very best by some team entrusted to pass judgment on whether they were among that team’s best ever.

There was the level of talent and accomplishment exemplified by pitchers of that ilk, and then there was the level above it. In slightly more that one out of every ten of his Met starts, 31 times in all, Dwight Gooden went up against a guy from that tier: a starting pitcher who eventually did have his number retired by somebody. In chronological order of the first time Gooden faced them, that circle includes:

Nolan Ryan

Fernando Valenzuela

Mike Scott

Steve Carlton

Jerry Koosman

Dennis Eckersley

T#m Gl@v!ne

Don Sutton

Greg Maddux

John Smoltz

Pedro Martinez

Those are all great pitchers, but a caveat applies here. Few of these pitchers were at their apogee when they swapped half-innings with Doc, and not every one of these pitchers had his number retired by the team he pitched for when Doc was his mound opponent. Koosman, for example, was in his last go-round, as a Phillie, wearing a number, 24, that we don’t associate him with at all. We know him as No. 36 for the Mets, an identity reinforced when that very number was added to the Met pantheon in 2021, a sign that the Mets were doing their own bit of bending, rewriting or casting aside “rules” because they knew in their gut that Kooz, who won more games for the Mets than anybody not named Tom Seaver or Dwight Gooden, belonged up there.

Jerry was of the same generation as Ryan and Carlton and Sutton, all coming along in the 1960s. Eckersley, who’d succeeded as a starter but excelled as a reliever, was a product of the 1970s, the same decade that offered a first rough (if not yet sandpaper-rough) glimpse of Scott. Valenzuela preceded Doc to the majors by four seasons, coming up in late 1980 and inspiring a mania all his own in 1981. Maddux, Gl@v!ne, Smoltz and Martinez all debuted during the Doc sequel years. The box scores confirm that every one of them was, for at least a spell, a contemporary of Gooden’s. Steve Carlton goes back so far that the Polo Grounds still stood when he signed his first pro contract. Pedro Martinez is recent enough that he pitched at Citi Field.

Yet, regardless of date of birth or date of debut or date of last pitch thrown, none exactly strikes me as a peer of his, and I think I understand why. Because as a Mets fan who lapped up every thing Doc did in 1984 and 1985 and doesn’t disown his performance from the other years, I believe Gooden had no peers. He was Doc. He was ours. He was the best when he was doing what he was doing, especially but not exclusively at the outset. In my heart, Doc was never anything less than a blockbuster.

Those mound opponents of Doc’s, the ones with their numbers retired by somebody, were absolutely some of the best of their time, maybe all time. Eight of them have their names on the kind of plaque Dwight Gooden will likely never have. Yet I took Doc over every single of them when Doc faced them, and I would take Doc over single one of them in the abstract, even the ones whose résumés lapped his.

I’d take Doc over any pitcher he ever faced, which in the days Doc was pitching for the Mets meant only pitchers who pitched for other National League teams. From 1984 to 1986, prime Gooden time, one pitcher who certainly belongs atop any list of greats from any era happened to be finishing his career in the American League, first with the White Sox, then with the Red Sox. There was no head-to-head between Doc and him, thus no reason to envision a contemporary mound duel for the ages. Still, I have to ask myself one more question, one I can’t look up on Baseball Reference:

In the abstract, would I take Doc Gooden over Tom Seaver?

Answer: I don’t have to. Sunday will make official what we’ve known in our collective gut for nearly forty years. There’s Tom, then Doc. There’s no taking one over the other, because they go together. If you’re not feeling it in your gut, get a gander at 41 and 16. From now on, you’ll know precisely where to find them both.

by Jason Fry on 13 April 2024 8:47 am When your team’s bad you spend a lot of time fuming about how it should be made good. This guy who’s failed too often needs to lose his job to this guy who hasn’t failed yet, any fool can see the lineup should be revamped so it works like this, etc.

I’m not generally one for half-measures, so my favorite proposed remedy is to declare that the Powers That Be should DFA everybody, which has never happen but would indeed sure show ’em. I have on occasion gone a step further and advocated that the Mets be contracted, though that usually requires them to have offended me by doing something truly dreadful, such as losing six of seven.

That’s the formula for bad times. When your team’s good, on the other hand? Lips tend to stay zipped. Nobody wants to offend the baseball gods, those capricious beings capable of directing batted balls past or into gloves. And, really, what is there to say?

On Friday night the Mets beat the Kansas City Royals, who’d won seven straight and attracted all sorts of accolades for their youth and dynamism, by the rather convincing score of 6-1. They got key hits and airtight defense from Brett Baty, solid work from Luis Severino and the bullpen, a no-doubter of a homer from Pete Alonso, and a ridiculous number of two-out hits. Seriously, the last part was mildly absurd: Ten of the Mets’ 14 hits came with two outs, and five of those timely tallies drove in runs. No wonder Michael Wacha, our old friend from the bell jar 2020 season, spent a good chunk of the evening stamping around the mound looking consternated.

“Don’t make a third out” isn’t a particularly replicable formula, so maybe just shrug and enjoy that part, but it wasn’t all the baseball gods deciding to scatter rose petals: Beyond Baty’s welcome continuing maturation (or at least his continuing run of confidence-breeding good results), Jeff McNeil looks more like his old self of late and Harrison Bader‘s bat has come alive. Severino’s pitches didn’t strike me as particularly sharp, and he lost the plate at times, but his last act was to fan Royals phenom Bobby Witt Jr. with KC threatening to make it a game again, and that final line is undeniable regardless of how many caveats you attach to it.

It’s also not like the Mets are firing on all cylinders. The baseball gods have apparently forgiven Brandon Nimmo, but both Starling Marte and Francisco Lindor have hit in oddly poor luck. Oddly for them, of course; it’s not odd at all for someone in the lineup to be suffering a run of misfortune, just as it isn’t odd for someone else in that lineup to be enjoying unexpectedly good results when meeting ball with bat. (Not to ruin a good story, but so far in 2024 that’s Baty.)

The fans greeted Lindor with standing Os, offering an antidote to some vile social-media drive-bys on his family; there hasn’t been the same mutterings or poor behavior about Marte, probably because everyone’s still glad to see him hale and hearty again and he’s less of a heart-on-his-sleeve player than Lindor, which gives onlookers less to react to. (Also: Even if I were reincarnated as a skeevy Internet troll, I would prefer to not have Starling Marte angry at me.)

Lindor expressed his gratitude, saying being cheered “fills my heart” (aw); one imagines a few more balls touching down on grass would have the same effect. Maybe the baseball gods will grant that wish next. Or maybe they won’t. We’d never presume to tell them what to do, after all.

by Greg Prince on 11 April 2024 8:37 pm The season began with plenty of warning, yet I found myself scrambling in the hours before and after Opening Day to update all the things I keep track of once the season is underway. The files I maintain for my and occasionally your amusement/edification looked like the aftermath of a party nobody had bother cleaning up from before turning out the lights on 2023. Damn, I had all winter to get these ready, yet I haven’t touched them since early October. Some things I monitor are germane to the dawn of a new year, others specific to baseball’s daily nature, others kept in reserve for when a specific oddity occurs.

It took me a few games to regain my keeping-track rhythm, but now I’ve returned to my groove. And, oh by the way, so have the Mets! On Thursday afternoon in Atlanta, they appeared to be the team that too often creams them, winning by a score of 16-4 while simultaneously pinning a loss on the Braves by — what a coincidence — that very same score. I may have been hallucinating, but I could swear I saw an awfully familiar utility infielder pitching for the team that was hopelessly behind.

The Braves are rarely hopelessly behind the Mets, either in a game or in a season, but some days surprisingly don’t belong to them. This one was the Mets’. My track-keeping fetishes and I happily shared it.

Facts that fascinated me in and around a matinee:

• The Mets were delayed by 42 minutes at the start. Not so fascinating, but it became their first rain delay of 2024 not to become a rainout (they’ve had four of those already). After a particularly soggy spring and summer a few seasons back, I began keeping track of how many minutes the Mets are delayed in a year. In 2023, we stood around and stared at our shoes for more than eighteen hours before somebody, one way or another, said ball could or couldn’t be played.

• After the offense had woven enough of a cushion in support of Jose Quintana and Drew Smith, Carlos Mendoza was confident enough to tell 29-year-old rookie lefty Tyler Jay to come on in, the lead is wide. Jay is a journeyman’s journeyman who persevered through quite a journey to replace Dedniel Nuñez on the roster and become a) the 1,233rd Met overall; b) the 427th player to make his major league debut as a Met; and c) the eighth Met in this century to feature a last name that ends in “ay”, joining Ruben Gotay (whose pronunciation of choice didn’t prepare him for this little club), Darren O’Day, Lance Broadway, Jason Bay, Trevor May, Sam Clay and Anthony Kay. Also, Jay, the latest temp to punch the clock in our gig economy bullpen, gave up a run while recording six outs, which stands as his most vital statistic, but you can track down that information anywhere.

• Luis Guillorme (pity it’s not GuillormAY) became the fifth Old Friend™ to compete versus the Mets this season, though the only position player to pitch against them thus far. In the non-trademarked Almost Acquainted category, we saw Allan Winans, a former Met farmhand, start for the Braves. We also lit him up for five innings. (Neither Travis d’Arnaud nor Jarred Kelenic were involved in this game, though they did show their faces earlier this week.)

• Amidst this backdrop of romping giddiness, word arrived that Julio Teheran, a Met in whom we invested our allegiance for the very first time a whole three nights earlier, was outrighted to Syracuse, declined the assignment and declared free agency. This means Julio — pending a Recidivistesque turn of events — has been set aside for next year’s edition of the annual Mets Who Have Left Us salute, a holding area where Phil Bickford (let go during the latter stages of St. Lucie sorting, only to fall in with a bad crowd), Michael Tonkin (swapped to the Twins for Cash Considerations, a name that must have been hell to carry around the schoolyard) and Yohan Ramirez (not good enough for us, but suddenly worthy of being an Oriole) find themselves loitering. Keeping track also means looking ahead.

• The 16-4 victory, enabled by 16 Met base hits and nearly as many Brave misplays, was the first 16-4 victory for the Mets since April 19, 2005. Our blog was just over two months old; Tyler Jay was celebrating his 11th birthday. The Mets hit seven home runs that night in Philadelphia, then a franchise record. On Thursday, only DJ Stewart and Tyrone Taylor went deep, but Stewart had a man on and Taylor’s was a grand slam. Sweet Sixteen, indeed.

• The Mets have now played one-dozen games in 2024, or their 2,988th dating to Opening Day 2005. When they play another dozen, Faith and Fear in Flushing will reach a triply grand milestone: 3,000 consecutive regular-season Met games blogged. THREE-THOUSAND CONSECUTIVE GAMES BLOGGED?!?! Really and truly. It sounds like a lot. It is a lot. It’s what happens when you stay with something relentlessly into a twentieth season. But you have to keep track of things to be aware of what you’ve done.

by Jason Fry on 10 April 2024 12:18 am It’s a tenet of our blog that there are no moral victories in baseball — the loss column comes without asterisks, parentheses or stuff in superscript. Moral victories are losses.

Well, except when one of us declares that moral victories do too exist.

Maybe I was just in a good mood: Monday night’s game found me and Emily in Buffalo, where we’d gone to visit an old friend and hopefully experience a total eclipse. The eclipse part was largely spoiled by a blanket of clouds, though even without a clear view of totality the experience was still pretty cool: three minutes of nighttime followed by the light coming back up like God had flipped a cosmic dimmer switch. (Though two hours later the skies over Buffalo were totally blue, grrr.) The rest of the visit was great fun, though — so much that I left Julio Teheran to his struggles for dinner, then returned to the fold after a surreptitious glance at Gameday informed me of the heroics of Brandon Nimmo and DJ Stewart. I watched the ninth on my phone, without sound, and this morning had to double-check that they’d actually won, because what I’d seen seemed so profoundly unlikely.

It was a win to put a little extra pep in one’s step, so much so that I largely shrugged off Adrian Houser getting tattooed when Tuesday night came around. I’d prefer Houser not do things like that of course, but the current incarnation of the Braves may be the most terrifying offense I’ve ever seen assembled, and it’s more of a surprise when a Met hurler doesn’t get mauled by them. I was less philosophical about the Mets repeatedly short-circuiting their own offense in particularly frustrating fashion, with leadoff baserunners erased through mischance or their own dunderheadedness, but hey, don’t watch baseball if you can’t handle the idea that the universe is perverse and cruel.

I was also cheered by the subtraction of Teheran, though I mean no slight against him or his long-ago Bravedom. Rather, it’s that I was cheered by the Mets evidently concluding that young, homegrown Jose Butto deserves that chance more than a retread whose ceiling is that he can give you innings, whatever that means. It wasn’t so long ago that the Mets sent Tommy Milone to the mound over and over again to be a metronome of suck, leaving me spluttering in rage by the end of the summer. Those Mets would have given Teheran the ball until Tylor Megill or perhaps Kodai Senga returned, greeting each loss with wide-eyed horseshit about veteran leadership and clubhouse presence; these Mets thanked him for his service and moved on after that first trial balloon deflated.

And there was Dedniel Nunez, thrown into the lion’s den in his first big-league go-round. Nunez showed both good stuff and admirable poise: Most pitchers making their debut look like they’re on the verge of hyperventilating through their first batter, if not their entire appearance, but he stayed cool and collected even as bad luck and his defense conspired against him. Collecting your first three big-league outs by retiring Ozzie Albies, Austin Riley and Matt Olson? That’s doing it the hard way.

And all that came before the Mets awoke from having slumbered through the pitching tenure of journeyman Reynaldo Lopez. Pete Alonso‘s three-run homer cut the deficit in half in the eighth, and the Mets added two more runs in the ninth via the unlikely combination of Harrison Bader and Omar Narvaez. Alonso batted with the game suddenly to be decided and it turned out he didn’t have a second thunderbolt in him: He went down on a nasty changeup from Raisel Iglesias, putting this one in the books with the Mets a run in arrears.

But still. An encouraging debut, a roster move to applaud, and a spirited comeback that forced the Braves to use personnel they’d have preferred to keep far from the action? That’s not a win, granted, but it’s not unpraiseworthy.

Or, like I said, maybe I was just in a good mood.

|

|

Now that we know, I’m in a place I didn’t expect to find myself: underwhelmed.

Now that we know, I’m in a place I didn’t expect to find myself: underwhelmed.