The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

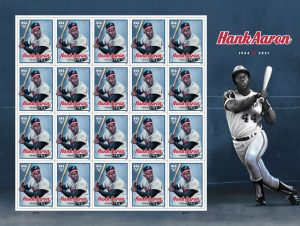

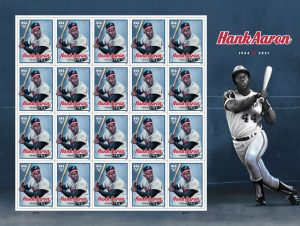

by Greg Prince on 9 April 2024 11:24 am By some stroke of coincidence, the Mets have visited Atlanta on the 30th, 40th and 50th anniversaries of Hank Aaron’s 715th career home run, which is swell, because what decent baseball fan doesn’t adore and revere the legacy of Hank Aaron? The Mets have to play the Braves at some point of every season. Might as well do it when one of the greatest players and achievements the sport has ever known is being commemorated.

The Mets weren’t mere spectators for this particular celebration of Hammerin’ Hank. They paid their own tribute by recreating the final score of the final game in which Aaron himself homered against them. That one, on July 17, 1973, finished up Mets 8 Braves 7 at what was then known as Atlanta Stadium, with not only Bad Henry contributing to the Atlanta offense in trademark fashion, but his fellow legend Willie Mays driving in what proved to be the winning run. For twenty seasons, so much of what made the National League special was defined by this duo. Aaron, now with 698 home runs, continued on his march toward surpassing Babe Ruth’s record the following April 8. Mays, who was sitting on 657 of an eventual 660 home runs, wound down toward saying Goodbye to America on September 25. They never again shared a box score.

The long view shouldn’t obscure what a tremendous comeback the Mets forged that night in a season that would have an even bigger one for them waiting come fall. Tug McGraw started, itself a story in that Tug was having the worst relief season of his life and Yogi Berra assigned him this start to snap him out of whatever was messing with the screwballer’s mind. Tug threw six innings and gave up seven runs but began to find himself. Meanwhile, with Aaron, Ralph Garr and Marty Perez all going deep, McGraw and the Mets fell into a 7-1 hole. Their 8-7 victory implies they dug their way out. They absolutely did, via a seven-run ninth. Rusty Staub homered with a man. John Milner — who was known as the Hammer, an homage to Hank — homered with a man on. Ultimately, Willie did his thing to give the Mets the lead heading to the bottom of the ninth. This is where a Mets fan of the early ’70s would expect Tug McGraw to come in and attempt to slam the door. Ah, but as noted, Tug started, so Yogi called on Harry Parker for the save opportunity. Harry struck out Darrell Evans and Sonny Jackson before getting Dusty Baker to foul out to Milner at first.

Mets 8 Braves 7. It reads so nice, the franchise decided to do it twice…technically an eighth time, as the Mets have beaten the Braves by this exact score on more occasions than you’d suspect, but let’s not get in the way of history rhyming, if not repeating.

With Aaron’s legacy in the spotlight and Baker visiting the SNY booth, the Mets a little too respectfully fell behind Atlanta, 4-0, early. Julio Teheran, whose name is familiar within the realm of Mets-Braves recaps, pitched in road grays while toeing a rubber he presumably knows well. Two innings as the Mets’ starter of next resort went all right. The third went about as well for the Mets on the 50th anniversary of 715 as the fourth went well for the Mets on the 30th anniversary of 715.

I should probably explain that.

On April 8, 2004, Dan Wheeler was the emergency starter for Art Howe’s Mets, forced into action when Scott Erickson, at the Julio Teheran stage of his career by then, was the latest of late scratches. Wheeler, a reliever who would pitch in the majors until 2012 without ever starting again, defused the perennial defending division champs’ offense wonderfully through the first, the second and the third. Staked to a 2-0 lead by a Ty Wigginton home run, a Mets fan thought his team might actually get away with something here. Then, in the fourth, Wheeler allowed a two-run double to Met-killer Johnny Estrada. The Mets took the lead back in the fifth, and Howe trusted Wheeler to stay in. Rafael Furcal doubled to lead off, ending Wheeler’s surprise start and opening the floodgates. The Mets went on to lose, 10-8.

In present-day Georgia, Teheran didn’t last as long as Wheeler, not after he yielded a two-run double to Ozzie Albies and a two-run homer to Marcell Ozuna. Two and two-thirds was all Julio could provide Carlos Mendoza, forcing Mendy to manage a bullpen game in which he was determined to not use the three relievers associated with the Mets holding leads…which didn’t seem like that much of a problem, considering the Mets trailed by four and this was Atlanta.

Hank Aaron slugged 40 home runs at age 40 in 1973, and it was, as viewed through orange-and-blue colored glasses, only the second-most remarkable feat in the National League that year. The Braves honored Hank Aaron on Monday night, and it turned out to be only the second-most gratifying event of the evening. We’re always happy to eclipse big doings in Atlanta. A single run in the top of the fourth, delivered by Starling Marte driving in Pete Alonso, didn’t hint that the spotlight would shift so dramatically. Brandon Nimmo taking Charlie Morton deep with two runners on in the fifth, however, indicated something was up, if not as far up as Brandon blasted his first homer of the season.

You watch the Mets at Truist Park, and you expect Travis d’Arnaud to do something harmful to them. Sure enough, he does that in the sixth, driving in the go-ahead run for the Braves off another pitcher-come-lately, Cole Sulser. Sulser replaced Yohan Ramirez on the roster Monday afternoon. Sulser didn’t give up anything else, though, same as Reed Garrett hadn’t given up anything at all once he took over for Teheran. Those relievers who are used when the manager doesn’t want to use the relievers he’d rather use sometimes come through somewhat.

Absolutely honor Aaron, but stamp the game as Nimmo’s. Back to Brandon Nimmo: he hit his second home run of the season, in the seventh inning. It was also hit very far. Nimmo trails Aaron’s career total of 755 by 666, but his two wallops Monday night indicate neither he nor his team should be counted out too soon.

Speaking of players who might have been counted out too soon, do you remember DJ Stewart? He approximated heroic for the 2023 Mets after all hope was lost for that sorry squad. Last August he drove in scads of runs before cooling off. DJ had a tepid Spring and was off to an icy 0-for-12 start, his ability to stand in the lefthanders’ batter’s box basically the only thing suggesting he’ll still be a Met once J.D. Martinez is ready to compete. But now those who make personnel calculations will be compelled to factor in the two-run homer Stewart produced in the eighth inning. It put the Mets up, 7-5, and it reminded onlookers that, right, right, not everybody who doesn’t hit for a week-and-a-half doesn’t hit forever. Recent home runs from Jeff McNeil, Francisco Lindor and Brandon Nimmo might have already told us that, but we require frequent reminders.

Hey, did somebody just mention Brandon Nimmo again? Well, they should have, because after Brian Snitker brought in lefty Jesse Chavez to face Nimmo, Nimmo knocked in his fifth run of what had turned into a robust affair. The Mets were up in the eighth, 8-5, and with Raley, Ottavino and Diaz out in the bullpen…

Oh yeah, they weren’t going to be used, because wins in Atlanta aren’t valued as much as resting relievers. So who else we got?

Jake Diekman, who followed Sulser in the seventh after Sulser followed Garrett in the sixth after Garrett followed Teheran in the third, walked the leadoff batter to begin the bottom of the eighth. Drew Smith, who’s edged into Circle of Trust territory of late, was rested enough to be judged eighthworthy. He followed Diekman. There was a lot of “traffic,” to use this year’s trendy vernacular, with walks and a wild pitch and acids in pits of stomachs, but Drew left the bases loaded, albeit after allowing one runner to walk home. The Braves had pulled to within 8-6.

The bottom of the ninth was not Edwin Diaz time or Tug McGraw time or Harry Parker time. The closer de la nuit was Jorge Lopez. Lopey, as Mendy calls him, has done some saving in his past, so why not? The retort might have been a) Matt Olson doubling and b) Ozuna doing something at least as bad had not Tyrone Taylor made a sparkling catch by the left field wall to keep Olson on the basepaths. Michael Harris singled to bring him home, and then Harris stole second, but a night that seemed poised to end as badly as possible got its groove back. Lopez induced a popout from Orlando Arcia and Old Friend™ d’Arnaud to fly out, and the scoreboard read at the end Mets 8 Braves 7.

Use it at will. It looks good in any year.

by Greg Prince on 8 April 2024 10:40 am “I was very fortunate to win three-hundred and eleven games, and not many people in the wonderful history of baseball were able to go past three-hundred,” said the man in the suit at the podium. “And you wonder why it happened? All you have to do is look at the individuals that were sixty feet, six inches away from me through a twenty-year career. How very fortunate I was to have three people that were my basic catchers through a twenty-year career, starting with Jerry Grote, ten-and-a-half years with the New York Mets.”

The man in the suit taking the time at the podium on a day that served as the capstone of his magnificent career was Tom Seaver. The podium’s location was Cooperstown, New York. And sixty feet, six inches away from the location he stood when he was making his case to someday be accepting induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame was indeed his catcher, Jerry Grote.

Nothing basic about Grote as a catcher, though. Tom knew that. We all knew that.

The mere fact that Jerry Grote was being mentioned as one-third of a triumvirate that included Carlton Fisk, who would be accepting the same honor as Seaver eight years down the line, and Johnny Bench, already enshrined as a member of the same exclusive club three years by then, spoke volumes. Close your eyes, and you can see Fisk and Bench hitting massive home runs. Keep your eyes closed and picture Grote. He’s catching.

He’s catching Tom Seaver. He’s catching Jerry Koosman. He’s catching Nolan Ryan. He’s catching Gary Gentry. He’s catching Don Cardwell. He’s catching Jon Matlack. He’s catching veterans. He’s catching rookies. He’s catching every Mets starting pitcher you can picture from 1966 to 1977, beginning with Jack Fisher (after Grote was practically stolen from Houston) and ending with Nino Espinosa (before Grote was mercifully traded to L.A.).

He’s the catcher to a generation and then some. We see him behind the plate. We see him up and at ’em, perhaps more than any Met ever got up and at ’em. Up and out of his crouch and after a foul fly. Up and out of his crouch and gunning a throw to second. Up and out of his crouch to get his pitcher on the right page. Up and on to great things for his team. Up and off to a splendid career of his own, one that earned him inclusion in the Mets Hall of Fame, where he is, per Seaver’s equation, one of three. Gary Carter is in there. He came later. Mike Piazza is in there. He came later. As with Bench and Fisk, they have plaques in Cooperstown. As with Bench and Fisk, they went deep dramatically and regularly. He’s the catcher to a generation and then some. We see him behind the plate. We see him up and at ’em, perhaps more than any Met ever got up and at ’em. Up and out of his crouch and after a foul fly. Up and out of his crouch and gunning a throw to second. Up and out of his crouch to get his pitcher on the right page. Up and on to great things for his team. Up and off to a splendid career of his own, one that earned him inclusion in the Mets Hall of Fame, where he is, per Seaver’s equation, one of three. Gary Carter is in there. He came later. Mike Piazza is in there. He came later. As with Bench and Fisk, they have plaques in Cooperstown. As with Bench and Fisk, they went deep dramatically and regularly.

Grote could hit some, but all you really see is the catcher. Grote could talk some, all his pitchers would confirm with a knowing chuckle, but they listened, because he was the catcher. Basic? Primary. He had some capable backups, but with everything on the line, Gil Hodges (who came up as a catcher) and Yogi Berra (in the Hall himself as a catcher) never looked beyond No. 15 from San Antonio. The Mets played twenty postseason games with Grote on their roster. Every inning and every pitch was handled behind the plate by one man.

I have a new favorite Jerry Grote stat, one I was moved to confirm on Sunday night, a few hours after the Mets had beaten the Reds in Cincinnati by a pitching-friendly score of 3-1, minutes after learning Jerry had passed away at 81. The legend of the 1973 Mets centers on their pedestrian regular-season record, inevitably processed as the best of a so-so assortment of contenders, implying they were some kind of fluke. Yes, they went 82-79, which in pre-Wild Card times usually meant you weren’t going to the playoffs. And, yes, the Mets had to pull themselves out of the last-place muck to get where they needed to go practically in a blink. One of the elements of the pennant drive that has survived anecdotally, at least among the Met faithful, is the Mets got going once they had their regulars healthy again.

How does that translate from anecdotal to statistical? Well, on May 11, the night Grote was hit by a Ramon Hernandez pitch and suffered a fracture to a bone his right arm, the Mets were above .500, sitting in second place, a couple of games from the division lead. The next time Jerry was in the starting lineup, on July 13, the Mets were languishing in last, way under .500, far removed from first place. Yet first place, with Jerry Grote taking every start down the stretch, is where the Mets ended up.

To borrow from Tom Seaver, “and you wonder why it happened?”

When Jerry Grote was in the starting lineup for the 1973 New York Mets, the record of the 1973 New York Mets was 47-29, the kind of pace that captures pennants. Jerry Grote made his pitchers better and made his team better. He also made his competitors’ eyes pop. Bench the slugger, who won ten consecutive Gold Gloves for the Reds from 1968 to 1977, famously said that had Grote been in Cincy, he himself would have been the third baseman. Lou Brock, the sultan of stolen bases, identified Jerry as his most effective nemesis. “He’s the toughest catcher in the league to try and steal against,” Lou said in 1968, the year NL players voted Grote to start the All-Star Game (Bench was his backup).

It was rewarding to know Grote won the respect of so many peers and rivals, but it was even better when you were a kid growing up as a Met fan to see the man in action. The way they used to televise baseball games, from behind home plate, No. 15 usually had his back to us. He’d be the first Met we saw. Then one of his pitchers would throw him a strike. We’d take in the entire picture and we’d figure out that the Mets stood an excellent chance of winning as long as our catcher was where we counted on him to be. Jerry Grote’s presence told us all that.

by Greg Prince on 7 April 2024 5:43 am As soon as you understand that a manager is going to try to “stay away” from using the relievers he relies on most, you also understand you’re going to need either a spit-ton of runs from your lineup or a comparable amount of innings from your starting pitcher. By the middle of the sixth inning on Saturday in Cincinnati, once it became clear the Mets’ starter was done, you understood the five runs the Mets had scored to that point, along with the three-run lead the Mets were holding, might be insufficient if your goal was victory.

And it wasn’t. Luis Severino gave Carlos Mendoza five gutty innings, which is to say one of them, the second, was a mess that did not quite spiral into something worse. The admirable work Luis — I’m not yet at the “Sevy” stage — put into extricating himself from the bases being loaded after two runs were home paid off in the short term, but almost guaranteed the long term wouldn’t be long enough. After 99 pitches through five, Severino was done.

The Mets led, 5-2, which was swell, given that the Mets hadn’t scored as many as five runs in a game in a week, but here came the “B” team out of the bullpen to back up the departed starter. Granted, the “A” team at any given moment might give you pause, and it’s quite possible that soon enough some pitcher on the “A” team might be relegated and a corresponding arm on the “B” team might be promoted, but for now, the vaunted Circle of Trust is real. For now, after so much recent usage of Drew Smith, Brooks Raley, Adam Ottavino and Edwin Diaz, Bob Murphy’s traditional ninth-inning instructions to fasten our seat belts carried extra resonance, and it was only the sixth.

Jake Diekman, one of our savvier offseason gets, per the assessment of those who make those pronouncements, came out of the pen with twelve outs to go. Two quick outs ensued. Great. Then Diekman walks Elly De La Cruz, hits Spencer Steer, and we’re antsily adjusting our shoulder harnesses. Pinch-hitter Stuart Fairchild singles to make it 5-3. Then there’s a steal of second that spawns a steal of home when nobody in road gray executes with big league precision, and it’s 5-4. Diekman squirms out of further trouble in could-have-been-worse fashion, yet you know in your bones it’s going to be worse.

It gets there, in the eighth, the second inning of work for Yohan Ramirez, whose seventh was effective. You wish for a reliever who can calmly deliver two solid innings and keep registering zeroes. It’s not impossible. Reed Garrett clamped down on the Tigers for three the other day (meaning he wasn’t available, either). Ramirez’s introduction to Mets fans was his taking one for the team by taking aim at the area behind Rhys Hoskins in the season’s first series. He heroically served a suspension. He was back to do something of greater value: get three goddamn outs and deliver the ninth inning intact to whoever was going to let Edwin rest.

Preservation of Diaz swiftly moved down the chain of priorities once the Reds and the eighth got through with Ramirez. Eight games into the season, it’s fair to call the bottom of the eighth Saturday a prototypical 2024 Mets defensive inning. Pitches missed when they needed to land. Fielders missed when they needed to grab. Bounces were unfriendly. And a big blow detonated. Without having the intestinal fortitude to pick apart the gruesome details, the tenuous 5-4 Met lead Ramirez was tasked with steering into the ninth transformed rather inevitably into a 9-5 deficit. The Met offense stirred in the ninth to add a run to its previously encouraging total, but the eighth and maybe the sixth had already told the tale.

New manager, new relievers, same problem in contemporary baseball, specifically contemporary Met baseball. Even when you have relievers you trust, you can’t send them out there every single day, yet you almost have to, because nearly every single day, starting pitchers thrill you if they get through five innings. Jose Quintana didn’t quite finish six on Friday night, a good outing, but an outing that led to calling on Smith and Raley and Ottavino and Diaz. Each of them had pitched on Thursday as well. The fan who’s been watching forever yearned for a Turk Wendell or a Roger McDowell to simply get up, get warm, get into the game and get the Mets through however many innings remained. Managers, whether they’re old hands like Buck Showalter or fresh faces like Carlos Mendoza, don’t do that sort of thing anymore. Also, it used to be unusual to have to get anybody cranking before the seventh. Contemporary baseball, Met or otherwise, operates differently.

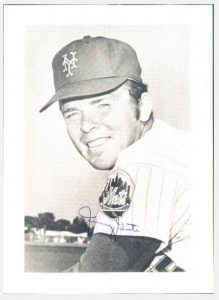

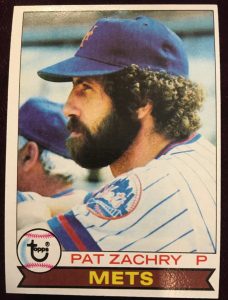

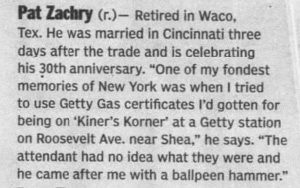

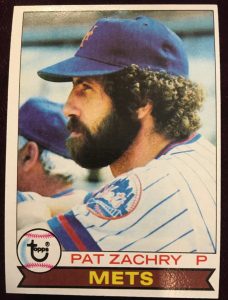

One necessarily comes to appreciate a pitcher like the late Pat Zachry even more against this tableau. Zachry, who pitched for the Reds and the Mets, died on Thursday a little shy of his 72nd birthday, following illness and personal tragedy. He was traded to New York on June 15, 1977, a date that still lives in infamy for Mets fans, though not because of anything related to the pitching or persona of Pat. You don’t replace Tom Seaver on the New York Mets in the middle of a season. You just hope to succeed him and that your best will occasionally surpass adequate.

To say Zachry was no Seaver is an exercise in obviousness. There was only one Tom Seaver, especially on the Mets. But Pat Zachry as Pat Zachry was pretty darn good. There’d be nights and stretches where you didn’t forget Tom, but you were happy to root for Pat. He didn’t make the All-Star team by accident in 1978 and he didn’t rate the Opening Day start merely by default in 1981. In tandem with Craig Swan, Zachry made us think, “OK, at least we still have some bona fide starting pitching.” You wished he’d stayed in one piece more often, because when he was healthy, he’d give you length and quality and confidence, the last of those elements too often lacking on the Mets clubs of his era.

No, no Tom Seaver, but go check out a few all-time career leaderboards where Met pitching is concerned. The tall Texan remains in the Top 25 in innings pitched and games started and ranks thirteenth in both complete games and shutouts. Complete games? What are those? Between 1977 and 1982, Pat Zachry defined the concept on a recurring basis, and every time he finished what he started, it meant one more day when Joe Torre or George Bamberger didn’t have to worry about who would have to be used in the sixth or seventh or eighth or ninth. The manager had his answer out there on the mound. No, no Tom Seaver, but go check out a few all-time career leaderboards where Met pitching is concerned. The tall Texan remains in the Top 25 in innings pitched and games started and ranks thirteenth in both complete games and shutouts. Complete games? What are those? Between 1977 and 1982, Pat Zachry defined the concept on a recurring basis, and every time he finished what he started, it meant one more day when Joe Torre or George Bamberger didn’t have to worry about who would have to be used in the sixth or seventh or eighth or ninth. The manager had his answer out there on the mound.

Most importantly, beyond statistics, Pat adjusted to life in a big city that was never on his radar, maintained good humor about some less than ideal professional circumstances (competitive intensity notwithstanding) and came across as a warm and decent soul to those who had the pleasure to get to know him even a little. That phrase about two seemingly contradictory things being true at the same time comes to mind: the Tom Seaver trade never should have happened, and we were lucky to have Pat Zachry. Most importantly, beyond statistics, Pat adjusted to life in a big city that was never on his radar, maintained good humor about some less than ideal professional circumstances (competitive intensity notwithstanding) and came across as a warm and decent soul to those who had the pleasure to get to know him even a little. That phrase about two seemingly contradictory things being true at the same time comes to mind: the Tom Seaver trade never should have happened, and we were lucky to have Pat Zachry.

by Jason Fry on 6 April 2024 12:51 am Baseball — perhaps you’ve heard — is a game of contrasts.

Take Hunter Greene vs. Jose Quintana, the starters for Friday night’s game in chilly Cincinnati. Greene is young, enormous and all but dripping talent, in possession of a high-90s fastball he can throw past big-league hitters as well as an evil slider tailor-made for embarrassing them. He used both to great effect against the Mets, retiring 10 in a row at one stretch and looking borderline unhittable in doing so. I can think of one bad slider that Greene threw all night — the one he hung to Starling Marte in the middle of the plate in the sixth. Marte’s swing caught too much of the bottom of the ball, and his look of disgust told you he knew that was the best swing the Mets were likely to have against Greene all night.

Quintana isn’t the physical specimen that Greene is, he isn’t young, and his arsenal isn’t one to elicit oohs and ahhs. And yet he matched Greene, bedeviling the Reds by shaving away at the edges of the plate and the upper and lower boundaries of the strike zone. Quintana was badly hurt on only one pitch: a first-inning sinker that didn’t sink, and that Spencer Steer sent away with a ticket to Kentucky, or near enough for a Reds’ run.

Another contrast came with two young infielders, Brett Baty and Elly De La Cruz, whose paths through the big leagues have been rocky in different ways. De La Cruz arrived as a jolt of human electricity, bringing power and speed and high-stepping flair, and looked like the game was too easy for him. Until the game reasserted itself and smacked him in the face. The flair is still present, but De La Cruz amasses strikeouts in bushels and his fielding has become hold-your-breath erratic.

Baty arrived with a home run in his first AB, but that was pretty much the last crackle of electricity — the rest of his rookie season was a humbling experience and his sophomore season was worse, both in terms of statistical results and in terms of intangibles that became distressingly tangible. You could see Baty thinking out there and you could also see that the thinking wasn’t helping him: the game speeding up as a grounder hopped in his direction, the strike zone expanding with a two-strike count, first base suddenly retreating to a million miles away when a throw needed to be made. By the time Baty was installed at third base this year, he was perilously close to going from prospect to suspect and getting labeled as one of those players who was never able to get out of his own way.

And who knows? Maybe that will be the verdict on Baty when verdicts get written. But Friday he had the kind of game you’d imagined for him from the beginning: a couple of hits, hard contact when making outs, and no ABs that snowballed and ran him over. And he was even better in the field, particularly in the sixth when De La Cruz smacked a ball to third. It was a tough chance for even the most sure-handed and confident infielder; as Baty moved to intercept it I was urging him don’t think don’t think don’t think. He didn’t — he scooped it up and fired a seed over to first, retiring De La Cruz by a step. A little run of games like that and maybe, finally, Baty will relax and become what all the scouting reports have said he can be.

When I wasn’t thinking about contrasts I was tempted to watch the game through the shutters of my fingers, because it was grinding and quietly terrifying. The Mets tied it at 1 on a sacrifice fly, converting a run out of an inning that featured a lone single, then took the lead on a what should have been a crusher of a double play off the bat of Pete Alonso that De La Cruz muffed.

It sure didn’t feel like it would be enough, particularly given recent late-game disasters. The Reds kept coming at the Mets and that skinny lead, with Drew Smith and Brooks Raley escaping trouble. The eighth inning, oddly, seemed to have parachuted in from some blissfully less stressful game, as Jeff McNeil lined a homer for a 3-1 run and Adam Ottavino looked the sharpest he’s been all year. But then Edwin Diaz was given an actual save to try and lock down and looked nervous and out of sorts. Diaz’s error on a comebacker put Jonathan India on first; he walked Steer; the Mets got just one out on what should have been a double play when Lindor and McNeil got their wires crossed at second; a sacrifice fly marked the second out but brought the Reds within one; and Diaz’s location was spotty against pinch-hitter Jake Fraley, with a wild pitch moving the tying run to third.

Disaster appeared nigh, but baseball is nothing if not a confounder of expectations. Somehow Diaz found a perfect slider — the Sugar Special that had been missing all inning. It might have been the only good one he threw all night, but it was the one he needed to retire Fraley. I’m not quite sure how the Mets won, but they did — you could look it up. They did just enough, perhaps, but just enough still counts as enough.

by Greg Prince on 5 April 2024 11:43 am It had rained for forty consecutive nights. The Mets had lost their previous fifty games. They had been no-hit for sixty innings in a row. Their most storied slugger was so desperate to effect change that he swung at a pitch seventy feet below sea level.

With one crack of the bat, the earth shook (eventually) and reality set in (immediately). It had been only two rainy nights, a five-game losing streak to start the season, and thirteen straight innings without a hit (and that little drought was snapped an entire inning earlier). Pete Alonso did swing at a pitch relatively close to the ground, but definitely above the dirt, and he made essential contact with it, driving it up in the air and over the fence in the ninth inning of a game the Mets were losing, in that way the Mets had been losing every game: hopelessly, lifelessly, chancelessly.

Now, however, the Mets had hope, had life, had a chance. They were tied with the Tigers, one apiece, in the bottom of the ninth at frigid, unpopulated Citi Field. Someday, perhaps, 500 people will claim they were there. After Alonso resuscitated the Mets’ DOA 2024 season with his second home run of the year and the 500th RBI of his career, actual baseball things began to happen for his baseball club…besides it finding a way to lose again. Brett Baty worked a walk. Starling Marte put the Mets’ new bunting craze to good use and moved Baty to second. And Tyrone Taylor — whose two prior base hits on the season placed him ahead of three bona fide Met regulars — lashed a low, outside slider well above the third baseman’s head and down the left field line, far enough to easily score Baty with what archaeologists classified the winning run.

Experts on ancient artifacts had to be called in for clarification, as nothing like it had been found on these premises in ages. Experts on ancient artifacts had to be called in for clarification, as nothing like it had been found on these premises in ages.

Alonso went down and got his pitch. Taylor went down and got his pitch. These Mets really did have to dig deep to excavate a single win on Thursday, a day they played twice and, until the ninth inning of the second game, produced little, except doubts. There was splendid home team starting pitching during the makeup doubleheader — five one-run innings from Adrian Houser in the opener and six from Jose Butto in the nightcap — but all that admirable hurling only seemed to accentuate how wretched the hitting had become. The Mets actually held a 3-0 lead in the first game, an advantage the Mets ceded slowly (single Tiger tallies in the sixth, seventh and eighth), before surrendering the contest all at once (luckless Michael Tonkin bending, then breaking in the eleventh). The meltdown portion en route to the 6-3 defeat was best captured by a text I received from Chuck, my best friend these last four decades:

Dude, seriously, I don’t know how u hang in there year in and year out. I am exhausted and it is only April 4.

It remained April 4 for the second game, but it might as well have been September 29, the scheduled date of the last game of this season, should the Mets endure as a going concern that long. The year was five games old and already felt over, no matter how repeatedly one muttered to oneself, “It’s still early.” The first eight innings of the nightcap — featuring a lone Met hit, from Harrison Bader — did nothing to disrupt the gloom.

Then Pete got ahold of one for one run, and the other fellows did what they did to build the other run, and the efforts of Butto and Reed Garrett in mostly shutting down the Tigers proved not in vain. The Mets, ahead 2-1 with an ‘F’ that could be repeated in polite company next to the score, came charging out of the dugout to heartily congratulate one another on finally winning something before retreating inside to fete Carlos Mendoza, a.k.a. Mendy, who now rates his clubhouse nickname, because a manager who has at last managed a win suddenly radiates humanity. Then Pete got ahold of one for one run, and the other fellows did what they did to build the other run, and the efforts of Butto and Reed Garrett in mostly shutting down the Tigers proved not in vain. The Mets, ahead 2-1 with an ‘F’ that could be repeated in polite company next to the score, came charging out of the dugout to heartily congratulate one another on finally winning something before retreating inside to fete Carlos Mendoza, a.k.a. Mendy, who now rates his clubhouse nickname, because a manager who has at last managed a win suddenly radiates humanity.

Watching the onrush of Mets in the wake of their walkoff, I took in what amounted to the first unposed team picture of 2024. 21? 13? 44? 75? I’m aware of which players wear which numbers, but in context, I was jolted into “who the hell are these guys?” mode. Right, right, they’re Mets I am depending on for brightening my outlook intermittently, blended in with 20 and 6 and 12 and 9 and 1 and 4 and 22, the guys whose identities I don’t have to question, except to wonder why 12 and 9 and 1 are 3-for-60 combined and what the hell ever happened to Lindor and Nimmo and McNeil.

Despite improving to 1-5 instead of declining to 0-6, Mendy and his Metted Men have a mountain to scale, and the Marlins (0-8) to thank for keeping them clear of the cellar. The starting pitching has been more than competent, but its depth is shallow enough to have created a need for Julio Teheran, a Met-killer of long ago, currently an arm whose most attractive aspect is availability. The relief pitching, Garrett’s scoreless three frames notwithstanding, tends to turn spotty at the worst moments. The fielding hasn’t done enough to keep bad innings from getting worse. And did we mention all that not getting a hit? Friday morning’s Metropolitan Area tremor surely wasn’t an aftershock from a torrent of Met offense. Despite improving to 1-5 instead of declining to 0-6, Mendy and his Metted Men have a mountain to scale, and the Marlins (0-8) to thank for keeping them clear of the cellar. The starting pitching has been more than competent, but its depth is shallow enough to have created a need for Julio Teheran, a Met-killer of long ago, currently an arm whose most attractive aspect is availability. The relief pitching, Garrett’s scoreless three frames notwithstanding, tends to turn spotty at the worst moments. The fielding hasn’t done enough to keep bad innings from getting worse. And did we mention all that not getting a hit? Friday morning’s Metropolitan Area tremor surely wasn’t an aftershock from a torrent of Met offense.

Yet it’s still early. And we’ve got a win. That’s the truth. Yet it’s still early. And we’ve got a win. That’s the truth.

by Jason Fry on 2 April 2024 12:09 am We could talk about Sean Manaea looking superb in a way that no Met starter looked against the Brewers, pitching aggressively and keeping the Tigers bothered and bewildered for six innings, with the lone blemish a sharp Andy Ibanez single to left with two out in the fifth — though that situation happily healed itself almost instantly, as Brandon Nimmo threw Carson Kelly out at the plate to preserve what was then a 0-0 tie. By the way, you want to be a catcher? Kelly — who plays that position for Detroit — slid hard into Francisco Alvarez at the plate, wrenching Alvarez’s head and neck to the side, got tagged hard in the nuts or uncomfortably thereabouts, and watched as his counterpart held onto the ball.

We could talk about Alvarez, who coolly made the kind of play it feels like catchers don’t make anymore, then showed the most offensive life the Mets displayed all night with a hustle double a few minutes after his close encounter with Kelly, not to mention a growing awareness of the strike zone and the need not to expand it in his other at-bats.

We could talk about Starling Marte, who looks better than he’s looked since that dreadful day two Septembers ago when a Mitch Keller fastball hit him in the hand and we didn’t yet know the Mets’ rocket ride had reached its apogee. We could talk about Brett Baty, who turned in a couple of crisp plays at third and looked like he had a plan at the plate, making you hope he’s finally ready to get out of his own way.

We could talk about those things, but who’d listen? Because the top of the 10th inning erased them all. With one out and the idiotic Manfred man having moved to third, Michael Tonkin in rapid succession a) hit old friend Mark Canha (this time at least the pitch behind an opponent’s back actually did get away); b) watched Joey Wendle make a dreadful error at second; c) instinctively tried to spear a high bounder from Gio Urshela and so turned an inning-ending double play into all hands being safe; d) almost managed the impossible task of walking Javier Baez, forcing himself to shrink the strike zone and giving up a sac fly; and e) surrendered a three-run bomb to Kelly that left the Mets five runs down and the fans jamming in the aisles in their haste to reach a safe distance.

Tonkin will have better days … well, provided he didn’t use them all up last year as a Brave, which is the kind of thing I think about all too often. Wendle can’t really do worse than a Mets debut that would make Mac Scarce or Chan Ho Park blanch, or at least I really hope he can’t.

Hell, I don’t know what will happen to those two: Baseball is cruel and confounding, with this 0-4 start just the latest reminder of that essential truth. What I do know is the Mets’ season is less than a week old and I’m relieved that they’re unlikely to be able to play baseball for the next two nights.

To be clear, I mean play baseball in the sense of “stand at the plate gripping a bat without being in danger of drowning,” not play baseball in the sense of “compete against another baseball team without it ending with an embarrassing and/or infuriating outcome.” So far the 2024 Mets have shown no indication that they can accomplish the latter in any kind of weather.

by Greg Prince on 1 April 2024 11:04 am Three games into the new season, and I already don’t want to dwell on the most recent baseball game the Mets played and lost. For the record, Tylor Megill labored for four innings Sunday and left with tenderness in his shoulder, slating him for an MRI. Carlos Mendoza served a suspension for Yohan Ramirez throwing in the general airspace around Rhys Hoskins the day before. Ramirez was suspended for three games but opted to appeal it, so fill-in manager John Gibbons used Yohan for three innings, a sure sign of an appeal likely to be dropped. The Mets did load the bases for a tantalizing moment in the fourth inning, albeit with two out. Omar Narvaez, the nine-hole hitter, was up, and I began to dream of Rusty Staub being deployed to pinch-hit, until I remembered a) Francisco Alvarez was the DH, so that meant — because we carry only two catchers — Alvarez would have to move behind the plate and we’d therefore lose the DH (stupid non-position that it is); and b) Rusty Staub hasn’t been available to pinch-hit in quite a while. Anyway, Narvaez hit for himself and gave a Colin Rea pitch a good ride, but his bid for a grand slam died at the warning track, as did the Mets’ last honest-to-goodness rally in their listless 4-1 loss to the now hated Brewers.

Stare into the neon and forget about the runs you can’t find on the scoreboard. The Mets must know how little we want to dwell on how they play, because they built many distractions into their season ahead of time. I saw a lot of what they were planning when they unveiled for the media their “NEW IN 24” chazerai, to use a word my mother would sprinkle into conversation when she wished to refer to random stuff, but do it with a touch of Yiddish. Citi Field’s chazerai is the stuff on the margins of baseball, like the way the 0-3 Mets will be lucky to be on the margins of the playoff race. Stuff like neon lights in upscale club spaces, and LED displays around every corner, and expanded retail operations, and more convenient ways to book a suite. Oh, and food, glorious food. Citi Field’s food has always been a winner, and a generous sampling by this reporter indicates it will continue to be so. (Pro tip: seek out Empanada Mama behind Section 103.)

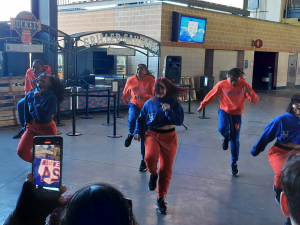

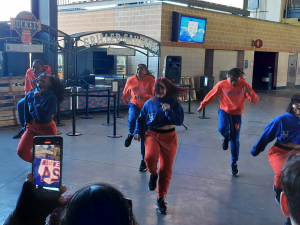

Met donuts don’t have as many holes as the Met lineup. The Mets were also kind enough to give visitors that chilly March day a sneak preview of the Queens Crew. The Queens Crew is the dance troupe you might have heard about. It’s a reflex reaction among Mets fans of a certain age to groan at the idea that dancers are being added to the baseball menu, because they didn’t have that in our day, let alone at our Shea. But y’know what? Time dances on, and maybe, as long as it’s between innings and the PA volume isn’t on blast, some people who aren’t me will enjoy it a lot. And I have to give these kids in the Queens Crew props for dancing in their thin getups on such a frigid morning. Seriously, they presented their first number in the left field corner, with the wind howling in so ferociously that it would have knocked down a Pete Alonso moonshot. Some of the young ladies (it’s a co-ed bunch) were sporting bare midriffs, and I was hoping somebody from one of the myriad team stores would appear when the music ceased to wrap them in blankets.

At least the Mets’ dancers showed up some pep in March. Despite accompanying my wife to the ballet a few Sundays a year many years ago, I’m no judge of dance, but these dancers showed some real skill and tons of enthusiasm. No, it’s not traditional baseball, but maybe we could use another distraction this season. Plus, there is a legitimate nostalgic element to bringing out a dance team at select home games in 2024. What wasn’t widely reported, but I’ve since learned, is that the Queens Crew is part of a reboot of one of the great Met anthems associated with the greatest of Met years.

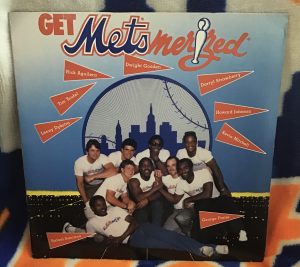

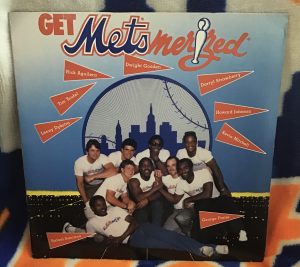

That’s right: they’re bringing back “Get Metsmerized”.

This Queens Crew truly knew how to kick it. Well, not bringing it back, exactly. They’re updating the song made famous during the 1986 season, the Mets’ bold entry into hip-hop, in which about a third of the roster — led by George Foster and including Darryl Strawberry, Dwight Gooden, Lenny Dykstra, Rafael Santana, Rick Aguilera, Kevin Mitchell, Tim Teufel and Howard Johnson — rapped their intentions to dominate the National League East and then some. You can’t say they didn’t make good on their prose or their promise.

The new version is called “Dance Metsmerized! 2024,” and it has quite a story behind it, per the Mets’ own hype. “‘Get Metsmerized’ was a landmark in the cross-pollenation between professional sports and an emerging art form,” the Mets’ press release detailing the new beats explains. “With ‘Dance Metsmerized! 2024,’ we’re adding a whole new layer to the timeless concept of ‘getting Metsmerized’. It provides us the opportunity to let our fans intimately know our newest personnel in a fresh and contemporary manner informed by old-school overtones, while providing a thumping soundtrack to the Queens Crew routines we’re confident Citi Field crowds will come to embrace. It’s baseball and diversity at its most ‘Amazin’!’”

Save a spot on your calendars for a “Dance Metsmerized! 2024” Day sometime this summer, sponsored by Danskin, Official Dancewear Partner of the New York Mets, with the first 15,000 fans through the gates getting sent to their devices a link that will allow them to download the song and its various remixes. By midseason, a vinyl version will be on sale at Citi Field concessions and through Mets.com, with all proceeds benefiting the great work done by the Amazin’ Mets Foundation.

“‘Dance Metsmerized! 2024’ strikes just the right balance of swagger and humility that the Mets have always been known for,” the release elaborates. “It may not be 1986 on the field, but you can bet at Caesars Sportsbook at the Metropolitan Market located on the Excelsior level that Citi Field’s world-class sound system will be pumping with ‘big league’ phrasing while the Queens Crew’s steps as they dance their hearts out atop the home team dugout will prove an inside-the-park home run!”

It’s admittedly a lot to digest. For copyright reasons, the actual music isn’t available for sharing yet, but fortunately, you can get a taste of “Dance Metsmerized! 2024” from the lyrics the Mets have furnished to various outlets (like ours). And you really do get to know better some of the new people the Mets brought in over the winter so they’re not just names on a stat sheet.

Honestly, with the Mets’ decision to play this little ditty “five or six times per game, including on our television and radio broadcasts, plus whenever fans engage with our social media accounts,” it would be foolish today or any day to think this baby won’t eventually be worming its way into all of our ears

***‘DANCE METSMERIZED! 2024’ OFFICIAL LYRICS

PRESENTED BY DANSKIN,

OFFICIAL DANCEWEAR PARTNER OF THE NEW YORK METS

QUEENS CREW

IN THE HOUSE!

QUEENS CREW

PLEASE ANNOUNCE!

Dance Metsmerized!

Twenty Twenty-Four!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for more!

Dance Metsmerized!

Hoofin’ on the roof!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for truth!

David Stearns

My passion burns

For baseball operations

Local guy

I’m flyin’ high

Makin’ calculations

Bringin’ in

Slight upgrades

At this an’ that position

We might compete

For a Wild Card

If we can’t win our division

Dance Metsmerized!

Twenty Twenty-Four!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for more!

Dance Metsmerized!

Hoofin’ on the roof!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for truth!

It ain’t where I came from

It’s where I’m goin’

I’m Carlos Mendoza

I impressed Steve Cohen

We’ll soon be better

At catchin’ and throwin’

And we’ll get bunt singles

If they’re not lawn-mowin’

Dance Metsmerized!

Twenty Twenty-Four!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for more!

Dance Metsmerized!

Hoofin’ on the roof!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for truth!

You say sooner

I say later

You say your name

I say Bader…

MY NAME!

BADER!

Hailin’ from

The Nine One Four

I’m the Mets’

Boy next door

Got my schoolin’

At Horace Mann

If you like defense

You’ll be my fan

Dance Metsmerized!

Twenty Twenty-Four!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for more!

Dance Metsmerized!

Hoofin’ on the roof!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for truth!

Some ask when-a

Some ask why-a

Don’t ask me

I’m Sean Manaea

My locks are shorn

My beard is shaved

Relax, Met-lovers

Your season’s saved

Dance Metsmerized!

Twenty Twenty-Four!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for more!

Dance Metsmerized!

Hoofin’ on the roof!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for truth!

‘YO, ADRIAN!’

I’ve heard it a lot

‘YO, ADRIAN!’

Feel free to stop

If ya wanna greet me

That’s okay

Just gimme a nod

Or gimme a ‘hey’

‘How’s it goin’, Houser?’

I’ll acknowledge, whatever

But that ‘Rocky’ bit?

Yo, it’s not clever

Dance Metsmerized!

Twenty Twenty-Four!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for more!

Dance Metsmerized!

Hoofin’ on the roof!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for truth!

I’m Joey Wendle

And I’m Zack Short

Some fantasy players

Can’t tell us apart

We’re utility guys

We know what we’re doing

We’ll try to be super

Like old Joe McEwing

Dance Metsmerized!

Twenty Twenty-Four!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for more!

Dance Metsmerized!

Hoofin’ on the roof!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for truth!

Popeye the Sailor

Lived on the sea

Tyrone A. Taylor

Yeah, that’s me

Flushing Bay’s

My port of call

Swing at everything

That’s my ball

Dance Metsmerized!

Twenty Twenty-Four!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for more!

Dance Metsmerized!

Hoofin’ on the roof!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for truth!

Severino, I used to be good

Severino, perhaps I still could

Severino, my price was alright

Severino, I go five tonight

Dance Metsmerized!

Twenty Twenty-Four!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for more!

Dance Metsmerized!

Hoofin’ on the roof!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for truth!

We’d introduce ourselves

But we’re just relievers

In this organization

We have few believers

If we give up earned runs

Then we’re off the team

We’re replaceable cogs

In the Met machine

Dance Metsmerized!

Twenty Twenty-Four!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for more!

Dance Metsmerized!

Hoofin’ on the roof!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for truth!

I’d be there with you

If they’d got me quickly

Without me there

The hitting’s sickly

I’m J.D. Martinez

A proven batter

I’ll be there soon

(It might not matter)

Dance Metsmerized!

Twenty Twenty-Four!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for more!

Dance Metsmerized!

Hoofin’ on the roof!

Dance Metsmerized!

Get ready for truth!

Now you’ve met

All our new faces

We could finish

In one of three places

Hope for the best

Don’t expect a whole lot

Mets fans know

The club they’ve got

QUEENS CREW IS OUT!

by Jason Fry on 31 March 2024 12:12 am Years ago, after too many not-yet-spring days spent at Shea watching it rain, waiting in horrible lines for bad coffee or both, my wife instituted a rule: No ballpark visits before May. In recent years, as I’ve become older and grumpier and more fragile, I’ve made her rule my own. I hope Opening Day is lovely, but I’ll see you when the trees have green leaves and the conversation is about returning the heaviest coats to the back of the closet.

So I was surprised bordering on shocked when Emily looked at the weather report and said it was going to be 60 and sunny on Saturday and we ought to go to the game. Off to StubHub I went, and at 1:40 pm we were sitting down the third base line in abundant sunshine, waiting to see how the Mets might fare in a second go-round with the Milwaukee Brewers.

The answer? Not to our satisfaction, though we’ll get to that. And maybe stick an asterisk or two on the verdict. We’ll get to that too.

One of the joys of the early baseball season is a simple one: getting used to the world reorienting itself around the game. Your nights and scattered afternoons are booked. Your phone alerts and Google searches return to looking up schedules and checking on prospects and fretting over medical reports. The first time back at the park is like that too, whether the visit comes in May or (gulp) late March: Is there going to be a 7 express? How do we do this again? And do the old routines, once remembered, still apply? Is there a byzantine new rule about things you can or cannot bring into the ballpark? Are there new displays? Attractions? Things to eat?

We got ourselves to the ballpark just fine (no 7 express though) and found the lineup now announces itself on video boards as you ascend the escalator. (A little gaudy but not bad.) The Mets museum has been relocated to beyond center field in favor of a far larger team store. (Eh, commerce gonna commerce.) We found some birra tacos and sweet corn (tasty), drank a cider and a beer and then got down to witnessing the business on the field.

From where I was down the third-base line I had no idea that Luis Severino‘s location was lousy, which it was — all I saw was baseballs struck by Brewers not finding their way into the right gloves at the right time. A lot of the contact was soft early — even the newly villainous Rhys Hoskins‘ first-inning double was more about location than velocity — but the later contact was not soft at all. When Hoskins connected in the third I didn’t even bother watching the ball’s flight, but just said a bad word and kicked at the cement.

The Mets fought back in fits and starts, with Francisco Alvarez socking a no-doubter home run in the second and high-stepping around the bases like a show pony, a sight that always makes me laugh and that I’d sorely missed. But the Brewers just kept pouring it on, with their crisp defense a sharp contrast to the Mets’ sloppiness, and by the time Severino was excused further misadventures I was just hoping someone in blue and orange would put some lipstick on this pig.

Lo and behold, the last three innings turned out to be pretty exciting.

The headline, inevitably, is that Yohan Ramirez threw behind Hoskins, a blatant bit of retaliation that earned him an ejection and a standing ovation from a crowd heartily sick of a steady diet of crow served up by our new least favorite former Phillie. The cheers for the heretofore anonymous Ramirez made me think back to Yoan Lopez earning plaudits from his teammates two Aprils ago for buzzing Nolan Arenado after Cardinal pitchers kept hitting Mets with baseballs. But I also needed to look up the details to remember Lopez had been the earner of said plaudits — my brain supplied “guy who was Adonis Medina before Adonis Medina.” Which, ehhh, really isn’t wrong.

As for the rest of the contretemps, I was amused to see Carlos Mendoza peddle the inevitable “no intent, pitch just got away” bullshit like a 10-year veteran skipper. Nothing that’s happened in the last two days has struck me as news: Rhys Hoskins straddles the hard to define but very real line between “hard-nosed competitor” and “kind of a dick;” Jeff McNeil‘s incessant chirping doesn’t endear him to his fellow players (ambush Francisco Lindor with some truth serum and see what information you return with); teams will protect their own and then swear, wide-eyed as choir boys, that they did no such thing; and retribution is pretty cold comfort when you’re getting your brains beat in.

When Adam Ottavino let in yet another run in the eighth I just sighed, and even let myself be mildly amused by Ottavino’s Eeyore demeanor, which is his affect even when things go well. Who knew that said run would turn out to be kind of important?

An amusing Fry family factoid: My mother watches every game, lives and dies on every pitch, and loves the Mets. But she cannot stand Brett Baty, whose serial failings draw a cold stare and a scornful “chew some more bubble gum, Baty.” So when Baty stepped into the box against Hoby Milner in the eighth I just shook my head, knowing my mother wouldn’t grade Baty on the curve for having to come off the bench to face a guy who’s not only a lefty but also a sidearmer. I still have no idea how Baty did what he did, but after he finished circling the bases I texted my mom a bunch of exclamation points, which she replied to with an only mildly grudging “OK Brett. Take a bow.”

Edwin Diaz entered to pitch the ninth, which was a nice moment even if a) he didn’t look his sharpest and b) there’s always something a little embarrassing about closer pomp and circumstance when there’s nothing to save. Though I must confess that when Diaz faced Hoskins I had a dreadful vision: Diaz would drill Hoskins, there’d be a brawl, and Diaz would emerge from it with his knee busted again — maybe the same knee, maybe the other knee, hell why not both knees? This is the kind of thing one imagines telling a therapist who’d then suggest that there are 29 other baseball teams and surely not all of them go about their business attended by an apparently permanent black cloud.

The bottom of the ninth saw the Mets get to within 7-6 but no closer, but that was another little personal victory: the one run (when we needed two) came on a Pete Alonso homer into the left-field stands, not a classic high arcing shot but a line drive whose destination was never in doubt. I’ve long mourned never seeing an Alonso homer live, which actually isn’t true: Greg (who knows these things) tells me I have seen one, though he allowed that it required replay review. I’ve now unambiguously and undeniably seen the Polar Bear doing what he was put on this earth to do, and it made me happy even when Starling Marte swung through a slider a few minutes later and it was time to go home.

The Mets lost, but they’re playing baseball again, Emily and I got to sit in the sun and see that baseball right in front of us, and the game was not without its pleasures and even offered a few surprises. Besides the ones covered, did you know the Mets now offer the 50-50 raffle? When I first encountered a 50-50 raffle at some park now forgotten I assumed it was an amusing local tradition; it took me a while to understand it’s a ballpark thing pretty much everywhere except New York. Now that that’s changed, there was no question that I was in for five tickets (or that I wouldn’t win, but oh well).

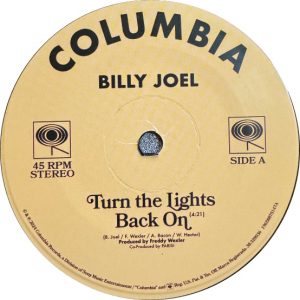

The Mets also inexplicably decided not to rig the ballpark singalong vote, leading to the man-bites-dog sight of “Piano Man” coming in behind the Killers’ “Mr. Brightside.” To be honest, “Mr. Brightside” moves at too speedy a clip to work as a singalong, plus everybody thinks they know the words but they actually don’t. No matter: It’s not “Piano Man,” which I’d rather be waterboarded than have to listen to. The Mets lost, but I was spared having to endure my least favorite song, and that’s not a bad way to start the year, even if other statistics point to work that needs to be done.

by Greg Prince on 30 March 2024 9:44 am Care for an omen? The Mets lost their last game of the season in 1968, a home game. They then lost their first game of the season in 1969, also a home game. That particular unpromising strand of homestanding Closing Day/Opening Day synergy hadn’t transpired again until they lost, 9-1, at home last October 1 to finish 2023 and then lost, 3-1, at home, on Friday to start 2024. Not all calendar-spanning two-game losing streaks are created equal. Some serve as prologue to unlikely world championships.

And some are just two losses in two different seasons. We’ll have plenty of opportunity to find out more of what the latest sample portends in the 161 games that follow.

One of the many Met coaches introduced on Opening Day might want to advise the hitters to start generating some electricity. If you don’t care for an omen, mostly what you got out of Opening Day 2024, beyond a plethora of pageantry and a return to routine, was Carlos Mendoza’s inaugural edition of the New York Mets being one-hit and their second baseman being slid into in chippy fashion. The one hit was Starling Marte’s second-inning home run, a good sign to all who remember those halcyon days of Marte’s considerable skills not being compromised by injury. The chippiness was furnished by former Phillie Rhys Hoskins, now wearing the Cub Scout garb of the Milwaukee Brewers after a year of rehabbing a torn ACL. You can take the Hoskins out of the Phillies, but Chase Utley proved Buttleyness lingers anywhere. Hoskins, charging from first on a grounder to third in the eighth, took Jeff McNeil out after an infield force. Jeff himself said he wasn’t going for the double play, so he didn’t know what the hell Hoskins was doing coming at him spikes up, other than being Hoskins.

Umpire review confirmed the slide was legal. In a previous era, it might not have raised an eyebrow, but sliding directly into a guy’s left leg is generally frowned upon in today’s preservation-minded version of the sport. I don’t blame McNeil, who plays now and not a hundred year ago, for expressing displeasure, nor the benches for emptying Harrelson-Rose style in response to the escalating yaps. As for Hoskins making a wah-wah! gesture from the safety of the visiting dugout, there’s no rule against McNeil bunting up the first base line today, is there? Pity if he runs straight into the Milwaukee first baseman. What’s his name again? He used to the play for the Phillies, I believe.

The Brewers’ starting pitcher, Freddy Peralta, was magnificent. The Mets’ starting pitcher, Jose Quintana, mostly navigated through trouble. We got some good relief from Drew Smith and Michael Tonkin, less good relief from Jorge Lopez. As Opening Day usually offers, there was a lot of window dressing. Festive as it is, it loses a little oomph when your lineup is all but impotent and your second baseman is mistaken for second base.

Maybe we all need time to get our act together. Early on, I watched a Francisco Lindor fly ball travel to right and decided it had a chance to leave the park. Maybe it was the wind, maybe it was my out-of-practice perception, but the ball was headed nowhere near the fence. In a split second, my thought process shifted from “keep going!” to “don’t go so far, maybe you’ll fall in!” It wound up caught by a Brewer, but it was comforting to know I’m still on speaking terms with baseballs.

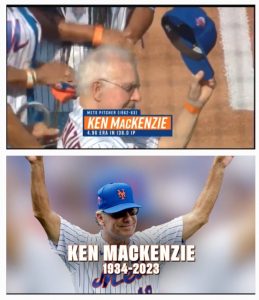

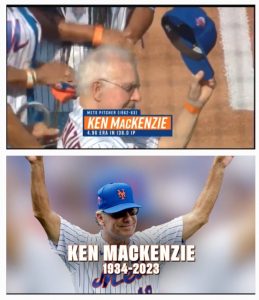

A bad omen for Opening Day might have shown itself in living color when the Mets couldn’t get through their pregame In Memoriam tribute without an unforced error. In attempting to remember lefthanded pitcher Ken MacKenzie (1934-2023), they displayed a picture of lefthanded pitcher Bobby Ojeda (1957- ). MacKenzie pitched for the Mets in 1962 and 1963 and died in December. Ojeda pitched for the Mets from 1986 to 1990 and, at last check, is still with us.

Top: Ken MacKenzie. Bottom: not Ken MacKenzie. The mistake that took a routine good intention and dropped it on the transfer — when will the Mets ever again have reason to devote enormous video screen bandwidth to their first winning pitcher, a gentleman who cherished his Met affiliation? — is almost understandable if you know that MacKenzie and Ojeda each wore No. 19 at Old Timers Day in 2022, just as they did in their Met tenures. The picture of Ojeda is that of a fellow above standard playing age wearing No. 19 standing and waving to the crowd on that occasion. It’s a nice picture. But it’s of Ojeda, not MacKenzie (who needed to be wheeled to the foul line to take part in those 2022 ceremonies). The Mets made this same mistake in initially announcing MacKenzie’s passing, but corrected it shortly thereafter, if not permanently within their files. Quality control that amounts to “I’m doing a search for an old dude who wore No. 19 less than two years ago in this very ballpark” apparently nets you more than one match.

by Greg Prince on 29 March 2024 3:48 am “What a break,” the player said. “Wow! This is great. I can hardly believe it. Imagine going to a club like the Phillies. I feel like I’ve been born again.”

The player was Buddy Harrelson, on the occasion of his trade from the Mets in Spring Training 1978. The Mets were founded in 1962 and were headed into their seventeenth season. Harrelson had signed with them in their second and had never been associated with anybody else. Born again? He was practically born a Met. How does somebody like that take such glee in assuming another identity?

“I kinda wondered about all that family stuff I’d been hearing for years. I thought I was a member of that family, but they didn’t have the decency to let me know they were getting someone to take my place.”

That quote is also Harrelson’s, uttered on the same occasion. During the preceding winter, the Mets dealt for Tim Foli, himself an ex-Met. Harrelson, 33 and oft-injured, understood the last-place Mets were going in a different direction. He didn’t understand why he couldn’t have been given a heads-up about Foli taking his spot while he was still on the roster. Thirteen seasons in a Met uniform didn’t mean much in the wake of 1977.

“If the Mets said I could have a lifetime contract to be a coach, I’d be crazy not to.”

The proprietor of that particular limited ambition? Mets coach Buddy Harrelson, August 1988. Buddy had filled in briefly for Davey Johnson and the Mets won the series he skippered. By then, Buddy had been back in the Met fold since the fall of 1981. A new Mets management structure recognized who Harrelson was and what he meant to the franchise. He’d been delighted to have been sent to a contender in Philadelphia, but “I never stopped being a Mets fan,” Buddy admitted when he came back the first time, “even when I was traded.” He also knew his baseball, and the Mets were smart enough to put what he’d accumulated to good use. He coached for George Bamberger. He announced over SportsChannel. He managed at Little Falls. He was in the third base box to urge Kevin Mitchell to bolt for home when a pitch got away from Rich Gedman and, a couple of moments later, he shadowed Ray Knight down the line. Now he was Davey’s right hand in the dugout. He wasn’t bucking for a promotion.

“The team was going to Philadelphia and I was going home to Long Island. I could have finished the week. The writers would have asked, ‘What about Harrelson?’ and they could have said they were deciding. In the winter they could have said, ‘He’s going to be a scout.’ That’s what hurt. They knew the heart of who I am and how I am. I earned better treatment than that.”

That’s Buddy Harrelson reflecting in 2000 on how the managing gig he wasn’t seeking in 1988 ended with seven games remaining in 1991. Frank Cashen was giving way to Al Harazin in the GM role, and it was decided somewhere upstairs that it would provide a fresher start for Harazin if he didn’t have to make his first official act the firing of Harrelson. Buddy had taken over for Davey in 1990 and led the perennially underachieving Mets’ charge into the thick of an ending era’s final pennant race. No, Buddy wasn’t gonna be back in 1992, nor, if you experienced 1991’s Met crash to earth, would have you thought he should be. But did they have to cut him loose with a week to go?

Between 1992 and 2000, Harrelson had been back to Shea plenty, no hard feelings evident, though “that’s what hurt” indicates some feelings remained harder than others. He’d even been enlisted, alongside Mookie Wilson, as a Mets community outreach representative after the disastrous 1993 season, when if any Mets were known for reaching out, it was so they could get better rotation on the firecrackers they were throwing. What more positive faces could you put on the Mets at any time than those of Mookie and Buddy?

“I never really wanted to manage. I’ve moved on.”

Harrelson’s direct association with the Mets was over by 2000, which was when he added the above thought. He was helping to start up and run the Long Island Ducks, an independent professional baseball team technically operating within the same Metropolitan Area where the Mets sold tickets, but the Ducks stressed they weren’t intending to take a bite out of any big league entity’s box office. Ticket prices were lower out in Suffolk. “We’re competition for the movies,” Buddy said. He had stayed on Long Island, and now he was doing something for his community. The Mets were his past. “This” — the Ducks — “might end up being my baseball legacy.”

Due respect to the pretty ballpark in Central Islip and the four Atlantic League championship teams to which it’s been home and however many kids who were introduced to baseball there because of the affordable tickets and cozy atmosphere, but no, that’s not Bud Harrelson’s baseball legacy. It’s great that Buddy had an enormous hand in creating, popularizing and sustaining the Long Island Ducks, but we know Buddy’s legacy is what he did as shortstop for the New York Mets, particularly the year the Mets first won it all and the year the Mets almost did that again. We might also add that the arc of his baseball life past those peaks of 1969 and 1973 speaks well for the idea that in this sport that begins again today in Flushing, you can go home again. You don’t have to be an alert third base coach to know the object of baseball is to go home.

Buddy Harrelson belonged in a Mets uniform, at the Mets’ ballpark. When the circumstances allowed it, he returned. Not only after he was traded as a player, not only after he was fired as a manager. When his calling card read Ducks, he’d still slip into something orange and blue and come home. In 2000, the same year the Ducks were first flapping their wings, Harrelson took a Sunday off to join his long-ago teammates at Shea Stadium. The occasion was the unveiling of the Ten Greatest Moments in Mets history, as determined by an online vote of the fans. When Buddy’s name was announced amid a slew of ’69ers, I had the sense (from his closeup on DiamondVision) that he was a little uncomfortable on the premises, as if someone in a suit might have intimated he was siphoning off business with that new Long Island team of his. But he showed up. He showed up on the final day of Shea Stadium, hopping atop home plate during the postgame ceremonies, and he was as special a guest as any alum during the 2009 and 2019 reunions of the 1969 champs at Citi Field.

And in 2024, the Mets will wear a memorial patch with his nickname and his number to commemorate his life and his legacy, because while a lot of things happen in baseball that don’t go down well in the moment — like being traded or being fired or being suspect — some people ultimately withstand and transcend those rough patches. Buddy Harrelson, No. 3, New York Mets. That’s who we remember. That’s how we’ll remember him. And in 2024, the Mets will wear a memorial patch with his nickname and his number to commemorate his life and his legacy, because while a lot of things happen in baseball that don’t go down well in the moment — like being traded or being fired or being suspect — some people ultimately withstand and transcend those rough patches. Buddy Harrelson, No. 3, New York Mets. That’s who we remember. That’s how we’ll remember him.

Eleven of the Mets who will wear the uniform that will feature the BUDDY 3 insignia, per the announced 26-man roster, will be brand new to the ballclub: starting pitchers Luis Severino, Sean Manaea and Adrian Houser; relievers Yohan Ramirez, Jorge Lopez, Jake Diekman and Michael Tonkin; infielders Zack Short and Joey Wendle; and outfielders Harrison Bader and Tyrone Taylor. A twelfth new Met, J.D. Martinez, will join them once he swings himself into shape. Martinez will be depended on to hit and to mentor, notably Mark Vientos, the promising youngster whose prospective job J.D. was signed to take. Vientos won’t be one of the Mets wearing the BUDDY 3 patch on Opening Day, either, as he’s been sent down to Syracuse. He figures to be back soon enough, and Martinez says he’ll be available to talk hitting with him or any teammate. “I’m an open book,” he said in St. Lucie. “That’s my passion. That’s what I do.”

The Mets are our passion, which is why we mope when our scheduled Opening Day is rained out, and we brighten when we realize tomorrow was only a day away. Citi Field, I can attest from a visit there last week, waited capably through the endless offseason and will be there to welcome our flock anew (plus it now has dancers!). What we do is revel in baseball’s arrival. That’s the theme entering today.

Then, at the first signs of adversity, perhaps before today is done, we grow antsy. It’s very likely in this ongoing era of roster churn that we won’t have to wait long to learn somebody among those ten new Mets has become an ex-Met…and his name will barely ring a bell months, maybe weeks later. It’s just as likely that one of the new Mets who sticks won’t succeed and mention of his name will wind up striking an unpleasant chord years from now.

Hopefully not the guy who sat on the market for months despite posting one overwhelmingly positive OPS+ after another for the past decade unless a pandemic happened to be shortening a season. Once March grew late, J.D. Martinez was simply too available to pass up, no matter the winter’s prevailing “let’s see what the kids can do” philosophy. May he bring to the (regrettable) DH role the kind of production and stability the Mets have lacked since the National League consented to have its rules bastardized. And if he can offer valuable insights to his designated successor, all the better.

“It’s part of the baseball tradition. They come up with new things in baseball, nowadays swing path and different things. There are things I can’t teach him. But at least I have experience. There are things I’ve lived and done. I definitely can share my experiences and knowledge with him. I can tell him what has worked and what hasn’t.”

What a gracious thing for 36-year-old J.D. Martinez to say about how he plans to relate to 24-year-old Mark Vientos. Except that quote isn’t from Martinez and it isn’t about Vientos and it’s not even from 2024. It was 35-year-old Adrian Gonzalez in 2018 looking forward to guiding 22-year-old Dom Smith. Different baseball players, yet similar baseball elements and sentiments, expressed a mere six years ago. When was the last time you thought about Adrian Gonzalez of the New York Mets? Or marveled at how well Dom Smith was doing?

It’s not the most hopeful of notes to scrawl across the clean slate of a new season, but we know how one minute you’re delighted that the only clouds on the horizon are puffy and cumulus, and the next minute a tarp is covering the infield. New Mets are offed in favor of newer Mets. Accomplished veterans impart only so much wisdom and have only so much left physically. Prospects fizzle. Franchises inevitably let legends leave in unseemly fashion — still. But like Bud Harrelson, who had every reason to remain disenchanted with his former employers, we never stop being Mets fans and we never stop coming back. All that family stuff proves real to us, season after season. It’s not the most hopeful of notes to scrawl across the clean slate of a new season, but we know how one minute you’re delighted that the only clouds on the horizon are puffy and cumulus, and the next minute a tarp is covering the infield. New Mets are offed in favor of newer Mets. Accomplished veterans impart only so much wisdom and have only so much left physically. Prospects fizzle. Franchises inevitably let legends leave in unseemly fashion — still. But like Bud Harrelson, who had every reason to remain disenchanted with his former employers, we never stop being Mets fans and we never stop coming back. All that family stuff proves real to us, season after season.

Happy new year. May you someday recall it well and recall it fondly.

A new episode of National League Town greets the new year. Listen to it here.

|

|