The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 27 March 2024 1:13 am Today we reach that year in the MY FAVORITE SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT countdown when I have to admit I went to sleep sometime in early April and woke up sometime in early November. That must be what happened, because I don’t seem to have any memories of anything that could have actually happened.

Fortunately, I stirred often enough over those seven months to keep a dream journal, writing down some of the surreal things, Metwise and otherwise, that apparently occurred in my subconscious. As I reviewed it for this series, I was struck by how surreal it reads. Like, I guess it could have happened, but, no, even now it comes off as a little too strange for reality.

Nonetheless, I’m sharing some excerpts below. I wouldn’t necessarily call them bad dreams. Far from it, for the most part. But I’d definitely call them weird dreams.

What a season I seem to have imagined…

***12. 2015

APRIL 6: I dreamed the Mets won on Opening Day in Washington, which doesn’t exactly feel like a dream, since they usually win on Opening Day, but the save went to journeyman Buddy Carlyle, which I wouldn’t have expected in my waking hours. Where’s last year’s closer Jenrry Mejia? I wonder if this is a harbinger of strange dreams to come.

APRIL 9: Matt Harvey is back, if my dreams are to be believed. He’s beating Stephen Strasburg again, just like that game I went to in real life in 2013 when we all chanted “HARVEY’S BETTER,” which is the only thing I can remember ever chanting at Citi Field. Are my dreams in reruns? No, this took place in Washington. Also, a guy named Alex Torres wore an oversized hat and pitched in relief for us, and I never saw a hat like that before. Also, isn’t the Torres who pitches for the Mets named Carlos? I don’t know if I need more sleep, but I need better sleep.

APRIL 11: Where was last year’s closer Jenrry Mejia on Opening Day? Per my latest dream, he’s been suspended for PEDs. Also, the Mets lost in Atlanta to drop their record to 2-3. Even in my dreams, the Mets can’t catch a break.

APRIL 14: I’m at Citi Field for Harvey Night. It’s the first Harvey Night since 2013. It doesn’t seem weird that Harvey is pitching again. We spent the bulk of last year reading every update about his Tommy John rehab. What’s weird is a) Chase Utley — we’re playing the Phillies — homers off him in the first inning (I must’ve been thinking about Utley’s Corner), as if Harvey gives up home runs; b) Harvey hits Utley in the fifth (do the Mets ever retaliate?); c) Utley hits another homer, this time off a pitcher named “Sean Gilmartin” (a combination of Gil Hodges and Billy Martin, maybe, reflecting my unease about Terry Collins still managing this team for a fifth straight season); d) David Wright steals a base, but then has to leave with some kind of injury (the words “day to day” float through my ears; e) Anthony Recker, the good-looking catcher (why do I notice he’s good looking in my dreams?) has to play third base in his stead, which is REALLY surreal even though the Mets have that crazy “79 Men on Third” history with that position, which David Wright seemed to have rendered moot; and f) the Mets win despite all the weirdness.

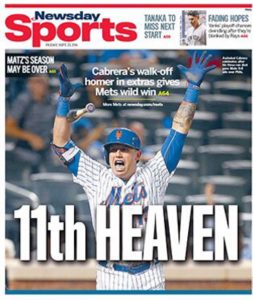

APRIL 23: I’m at Citi Field again, a weekday afternoon game. Wright still isn’t playing. The Mets are trying to tie their consecutive wins streak record at eleven, a mark they set in 1969 and have tied three times since but never broken. When they win eleven in a row, they always wind up having a winning record, which would be a nice change from what I’m used to as a Mets fan, having experienced nothing but losing seasons dating back to 2009 and the opening of the new ballpark. What are the Mets doing being unbeatable? In the dream, if the Mets win, they will have swept an entire three-team, ten-game homestand: the Phillies, the Marlins and the Braves, all hated divisional rivals. So many questions. Also, it is freezing, yet I am up and I am clapping and feeling very optimistic about the Mets, something I haven’t felt for more than five minutes in maybe seven years, probably longer. It’s like my cynicism has taken a holiday. “We’ll have to change our jaded ways,” Billy Joel once said, and I seem to have listened. Toward the end of the dream, the Mets do win their eleventh consecutive game — and our new closer Jeurys Familia saves his eighth, making it seem as if Mejia never existed. I’m loving these days?

MAY 6: Jacob deGrom, last year’s Rookie of the Year, beats the Orioles one night after Bartolo Colon does the same. I really like deGrom, though I find Colon a little too much of an Internet meme. “Jake and the Fatman,” I muse, and then tweet a picture of William Conrad. Good line, if a little pot calling the kettle black insensitive on my part. Can I help what material I come up with in my dreams? MAY 6: Jacob deGrom, last year’s Rookie of the Year, beats the Orioles one night after Bartolo Colon does the same. I really like deGrom, though I find Colon a little too much of an Internet meme. “Jake and the Fatman,” I muse, and then tweet a picture of William Conrad. Good line, if a little pot calling the kettle black insensitive on my part. Can I help what material I come up with in my dreams?

MAY 17: Back at Citi Field, a sunny Sunday afternoon. Noah Syndergaard is making his home debut. A lot of guys have brought toy hammers, like hammers of the gods from Norse Mythology, I assume, because his nickname is Thor. I must be dreaming, because I can’t believe security would let those through. Before I drifted off during Spring Training, I think there was something about Syndergaard (or “Thor”) eating lunch in the clubhouse during an exhibition game and David Wright telling him that’s a no-no, rook, and Bobby Parnell tossing it into the trash. Anyway, “Thor” is a Met now, according to my dream. Maybe he replaced Dillon Gee, who I don’t see anywhere. Gee, I always liked him.

MAY 20: My dreaming takes a dark turn. I’m supposed to be at tonight’s game, but I can’t go. Turns out the Mets get shellacked by the Cardinals and fall out of first place — the Mets are in first place? — but that’s hardly the center of the dream. In the morning, I get a call that my father’s been taken to the hospital, which gets me and my sister together to drive first to one hospital, then another until we find out which one he’s in. He fell at home, apparently. He’s there all day into the night, so I just can’t take off for a ballgame. Honestly, in the dream, I’m not too worried about the Mets. My father is checked in and staying for a while. Oh, and if all of this isn’t weird enough, this is the night David Letterman ends his talk show, three days after Mad Men airs its finale. I vaguely recall making small talk with my father about Mad Men while he’s lying on a gurnee in a hospital corridor. And wasn’t one of Letterman’s directors named Hal Gurnee? My dreams are getting weirder.

MAY 23: My worlds must be meshing because in addition to dreaming my father is a) still in the hospital and b) had to have brain surgery to remove as much could be removed of a glioblastoma, I learn David Wright — who hasn’t played in more than a month — will be out indefinitely with something back-related I have to Google (it’s something nobody’s heard of, but it’s not good). To make it all stranger, I seem to be driving back and forth from the South Shore, where I live in real life, to the North Shore, where my father’s recuperating, and I almost never drive any kind of distance. It’s all a little scary.

MAY 24: I’m visiting my dad in the hospital again. The Mets are on a TV, losing in Pittsburgh by a score of 9-1. The Mets won their first game ever in Pittsburgh by a score of 9-1. That was the year I was born, and here, in my dreams, I’m trying to get closer to my father, but somehow finding time to keep an eye on the Mets game and worry about Wright’s “stenosis” I think it’s called. What does it all mean?

MAY 30: I go the Mets game by myself. It’s all connected to my father being in the hospital in the dream. Everything about his condition and recovery and the family (ours and his girlfriend’s) is kind of closing in, and I just have to get back to something familiar, something with a different form of attachment. In the dream, I’ve chosen Pepsi Towel Day. I have a longstanding relationship to the beverage business, and Pepsi has a Porch at Citi Field, but the kicker in the dream is they run out of towels by the time I get to the ballpark. The Mets lose to the Marlins. That, somehow, doesn’t sound surreal.

JUNE 1 I dreamed an article ran in the New York Times about the Mets’ ancient third base problems and how they’ve revived with Wright out, how they’re suddenly using Ruben Tejada there. Thing is, in the dream they get the all-time number of Mets third basemen wrong — the article said 144 and I KNOW it’s 156 because I keep track — and it drives me crazy, even though I have bigger things to worry about, like my dad. I keep sending e-mails and tweets to the sports editor and the guy who wrote the story, even including Baseball-Reference links to support my assertion, yet they don’t do anything about it. Later in the dream, the writer winds up blocking me on Twitter and they never run a correction. But, for the record, I was right…or do I mean Wright?

JUNE 9: OK, this one might call for therapy. I’m visiting my father in the hospital, or whichever facility he’s in now. I come to see him almost every day, which is quite a switch of how it was when he was healthy. He’s coming along, which seems like an understatement — he had brain surgery less than two weeks ago (on the night THAT was happening, according to a dreamed memory I must’ve repressed, I was watching Noah Syndergaard pitch against another young fireballer, Gerrit Cole, as if it was important that I stay on top of the Mets), yet we’re holding conversations and they’re teaching him to get the hang of walking again. Anyway, toward the end of our visit, I tell him I’m going to the Beacon Theatre for an offseason football Giants event. Eli Manning’s gonna be there. Tom Coughlin’s gonna be there. My father gets a kick out of this, so it seems like a worthwhile fact for me to share with him. Next thing I know, after the Giants thing is over, I’m out on the street listening to the Mets game and I hear the Mets playing the BASEBALL Giants at Citi Field and some guy I’ve never heard of is throwing a no-hitter against the Mets. I’m totally confused by what all of this means. Is it because I’m fascinated by New York Giants baseball history and it’s split off in multiple directions? Is my father’s situation casting a giant shadow over the season? Am I worried that the Mets aren’t hitting and will therefore never hit again? The dream winds up with me listening to Howie Rose calling the play-by-play first outside Penn Station, then on a train home.

JUNE 10: I’m still having no-hitter dreams. I find Howie Rose’s ninth-inning play-by-play online somewhere and I decide to transcribe it, first on Twitter, then on the blog. I lose Twitter followers who don’t want to be reminded, and some blog readers tell me they don’t love being reminded. Yet in the dream I did it to be complimentary toward Howie’s play-by-play, particularly that he called it with the right amount of drama, never mind it was happening to rather than for the Mets, like Bob Murphy might have. The kicker to this dream? Howie Rose e-mailed me to thank me for making the comparison. No, this couldn’t have happened. MEANWHILE (yes, it’s one of those long and winding dreams), I go to a game that night, at Citi Field, against the Giants. It’s with a guy from California who tells me he’s moved to Queens for the season JUST so he can go to every Mets home game. I know, right? The guy, who tells me a book I wrote helped inspire him to do this, has very good seats not far from the field, the cushy green ones. At one point, I stand up, then sit down, and the seat collapses with me in it. In my dreams, this six-year-old ballpark is falling apart. JUNE 10: I’m still having no-hitter dreams. I find Howie Rose’s ninth-inning play-by-play online somewhere and I decide to transcribe it, first on Twitter, then on the blog. I lose Twitter followers who don’t want to be reminded, and some blog readers tell me they don’t love being reminded. Yet in the dream I did it to be complimentary toward Howie’s play-by-play, particularly that he called it with the right amount of drama, never mind it was happening to rather than for the Mets, like Bob Murphy might have. The kicker to this dream? Howie Rose e-mailed me to thank me for making the comparison. No, this couldn’t have happened. MEANWHILE (yes, it’s one of those long and winding dreams), I go to a game that night, at Citi Field, against the Giants. It’s with a guy from California who tells me he’s moved to Queens for the season JUST so he can go to every Mets home game. I know, right? The guy, who tells me a book I wrote helped inspire him to do this, has very good seats not far from the field, the cushy green ones. At one point, I stand up, then sit down, and the seat collapses with me in it. In my dreams, this six-year-old ballpark is falling apart.

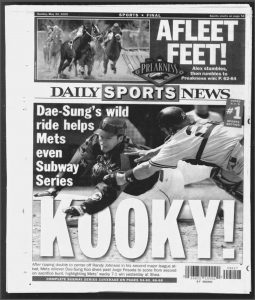

JUNE 14: In this dream, the Mets blew a lead yesterday, with the guy with the big hat (one of the Torreses, I think, still) blowing the save in the ninth and a guy wearing a normal-sized hat (the other Torres?) taking the loss in the eleventh; a horse named American Pharoah — spelled just like that — won the first horse racing Triple Crown in 37 years; and then the Mets storm from behind today to win. The racing metaphor must have something to do with the pennant race. That would make sense. Less logical are some of the names that keep filtering through my subconscious. According to the box score in my dream, one of the four Mets to hit a homer in the win was “Darrell Ceciliani”. Your guess is as good as mine as to who that is.

JUNE 18: This one feels like the culmination of a few things. There’s been a four-game series against the Blue Jays — two at home, two on the road. (Do they do that in real life?) First off, there’s a lot of Jose Reyes in this dream. He was traded at some point from the Marlins to the Jays, but deep down I’ve never stopped missing him on the Mets. Then, in the middle of a large Mets loss, there are two pitchers named “Jack Leathersich” and “Akeel Morris”. Where do these names keep coming from? Next, there’s R.A. Dickey beating us in Toronto. He’s another guy I’ve never quite made my peace with having been gone. But what really catapults this one into strange-dream territory is John Gibbons, the Blue Jays manager (and an ex-Met, make of that what you will), reveals that Dickey was pitching shortly after his father died. It’s too eerily similar to what I’m going through with my dad not to give me chills.

JUNE 25: The standings in my dreams indicate the Mets have slipped below .500, yet here they are for a change winning. DeGrom not only pitched eight shutout innings, but he gets a hit and scores the insurance run…and I’m listening to it in the lobby of a hospital that isn’t the one my father’s been in. We — me, him, my sister, his girlfriend — have just come to this other place for him to be examined and told he’s coming along. For a moment, I feel like I’m talking to my dad in some “normal” situation that just happens to be a hospital lobby. I take this to mean that they will be sending home soon, or that the Mets will be sending more runners home soon. Whatever it is, it’s one of the less disturbing dreams I’ve had of late.

JUNE 26: Latest bizarre setting in dreamland? One of those suites at Citi Field. What am I doing in a suite? Well, best as I can make out, a friend’s daughter is having her high school graduation party there. I know, go figure. I show up with my wife, and who do I see in the suite? Howie Rose AND Josh Lewin. Before I can say a word, Howie waves to me and says, “Hi Greg,” which is something I wouldn’t have dreamed when I started listening to him on the radio in 1987. I call my father from the hallway outside the suite. I’m a little cagey about where I am because I feel weird being at a game while he’s still in the hospital this Friday night. While we’re chatting, a very tall man walks by with an entourage. He’s wearing a Mets jersey but he’s supposed to be the Knicks’ first-round draft pick. Kristaps something. He’s from Europe and he’s throwing out the first pitch. These dreams’ details are heading off the charts.

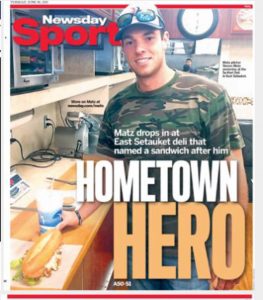

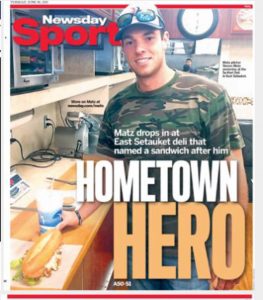

JUNE 28: My subconscious ain’t seen nothing yet. Today’s dream was a LONG one. I’m back at Citi Field, not for a doubleheader, but kind of a doubleheader, because apparently it rained a lot yesterday and that game was suspended — in the dream, I was there for that, too; it was a cold rain and the people behind me castigated me for opening my umbrella. Anyway, they have to finish the day before’s game, and that takes forever, because the Mets don’t hit, but they somehow win it. Lucas Duda drives in the winning run, which doesn’t sound like anything unusual, except in the dream, they gave out a “growth chart” with his picture on it. Then they play the regularly scheduled game, which is started for the Mets by a kid named Matz (a little on the nose) who’s supposed to be from Suffolk County, and everybody’s excited that he grew up a Mets fan. Not only does he pitch well, but he gets three hits and drives in four runs while his grandfather becomes a TV sensation by going nuts for the SNY cameras. So we sweep the pseudo-doubleheader and I stick around afterwards because STEVE MILLER? is playing a concert to like 200 people. He’s good, but it’s been a long day and I guess everybody else is itching to go home. In the dream, Steve Miller makes mention of “Stevie” Matz, like that’s what he’s called? I’m none among a joker, toker or midnight smoker, but I am confused.

JULY 2: My dad is out of the hospital and the Mets are being swept three by the Cubs while scoring exactly one run. Disappointing Met overtones asides, this qualifies as a good dream. JULY 2: My dad is out of the hospital and the Mets are being swept three by the Cubs while scoring exactly one run. Disappointing Met overtones asides, this qualifies as a good dream.

JULY 6: The Mets are in San Francisco. “Johnny Monell” breaks up a scoreless tie and we win. Where do these total strangers keep coming up and what do they mean?

JULY 11: Maybe because this is the same date that I went to my first game in 1973, I get a good dream for the occasion. I’m at Citi Field and Matt Harvey homers. Pitchers really do hit in my subconscious. I hate the designated hitter THAT much. I fuzzily recall Noah Syndergaard homering in late May, too, but that happened when my dad took ill, so I wasn’t able to dwell on it.

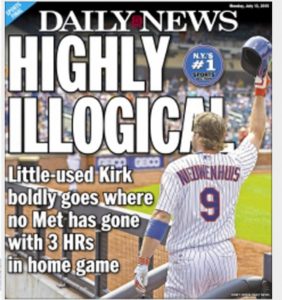

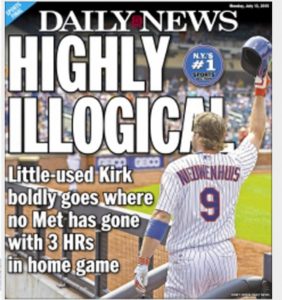

JULY 12: It’s the last game before the All-Star break and KIRK NIEUWENHUIS, who I think I dreamed wasn’t even on the team for a while this year, hits THREE HOME RUNS in a single home game, the first Met to ever do that at Citi Field or Shea Stadium or the Polo Grounds. Not Wright or Piazza or Strawberry or even the original Frank Thomas. Kirk Nieuwenhuis. Tell me I’m not dreaming.

JULY 19: It’s the Sunday after the All-Star break in this one. The Mets are in St. Louis and they play EIGHTEEN innings. I think the Mets won. I know Keith Hernandez got impatient (a very lifelike detail to have retained). JULY 19: It’s the Sunday after the All-Star break in this one. The Mets are in St. Louis and they play EIGHTEEN innings. I think the Mets won. I know Keith Hernandez got impatient (a very lifelike detail to have retained).

JULY 23: In this dream, the Mets are facing Clayton Kershaw, last year’s NL Cy Young and MVP. Who are they sending out to bat against him? I see names on a TV screen: Mayberry (didn’t he play for the Royals in the ’70s?); Campbell (am I secretly craving soup?); Recker (the catcher who played third base in my April dream). Bartolo Colon is the starting pitcher for us and he doesn’t even have the lowest batting average of the bunch. The Mets miraculously pound out three hits while Kershaw tossed an eleven-strikeout shutout. If somebody were awake while he came up with this Met lineup, I’d call it a nightmare.

JULY 24: I dreamed the Mets called up last year’s top draft choice Michael Conforto. The Mets never call up last year’s draft choice, so I must be dreaming. Unless they had the same nightmare about the lineup the night before that I did.

JULY 25: I wonder if I was sweating when I rolled over and went back to sleep, because this one feels like a fever dream. First of all, the Mets traded for major league help: Kelly Johnson and Juan Uribe. Random baseball names for my subconscious, but at least I’ve heard of them. Then the Mets, with me in attendance, stomp all over the Dodgers, 15-2, with those new guys helping AND Conforto getting four hits. Oh, and HEART — you know, “Magic Man” — plays a show afterward. The summer heat must be getting to me.

JULY 26: We’re still playing the Dodgers in my dreams. I’m at this game, too. I’m in the right field corner of Field Level with my wife and a bunch of people from where she works. That’s happened in real life, but on a Sunday afternoon? Against the Dodgers? Anything goes in a dream. Zack Greinke is pitching for L.A. and has this long scoreless innings streak, but who should drive in the run that snaps it? Jacob deGrom. He pitches great, but Familia blows the lead, it rains a little, and in the dream I’m really fatalistic. But then Jenrry Mejia, like from out of nowhere in my subconscious, returns to throw a scoreless inning, and Uribe drives in the winning run in the tenth inning. It’s also apparently the same day Pedro Martinez is inducted into the Hall of Fame, where he says something very nice about Mets fans. That’s the kind of thing I always dream of.

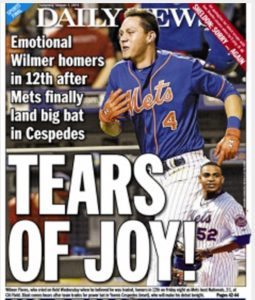

JULY 29: This dream starts in a doctor’s examining room. My father’s been getting radiation and taking chemo since leaving the hospital. The whole family is crowded in with him for a followup. He’s told he’s doing very well and can go about his life. He’s 86, but asks the doctor if he’s good for another “10 or 11 years”. The doctor doesn’t quite respond. I celebrate by letting a friend of mine know I will go to the game with him that night. Lucas Duda hits three home runs, just like Kirk Nieuwenhuis did a couple of weeks ago, but nobody notices, because the trade deadline is approaching and word spreads around the ballpark that the Mets are trading Wilmer Flores and Zack Wheeler (who’s been injured this whole time) to Milwaukee for Carlos Gomez, the guy we traded in a package to get Johan Santana in 2008. CARLOS GOMEZ? I don’t know where that name came from. The kicker is word spreads to the Mets dugout and somebody tells Flores, who’s getting appreciative applause from the stands, and he gets all sad and the TV cameras pick up that he’s playing with tears in his eyes and my friend and I ask each other what the hell he’s doing in the game? Then, maybe just before I woke up, Sandy Alderson shows up to say there is no trade. Holy crap, go figure that one out.

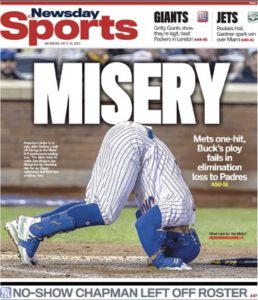

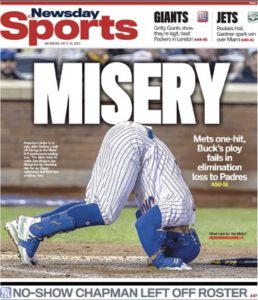

JULY 30: I’m at Citi Field yet again for an afternoon game. Everybody’s talking about Flores, but he isn’t playing. The Mets are beating the Padres, which is great, except it starts to get overcast, and there’s a late rain delay, and Familia comes out to get the save, but he doesn’t get it. One of the Uptons (I forget which one) hits a home run to put the Padres in the lead and it starts to rain again, really hard, and I give up and go home. Next thing I dream, I walk into my living room and turn on the radio to hear the Mets are still in rain delay. They eventually lose. Funny thing about this dream is everybody seems convinced the Mets are cursed, yet I notice they’re still close to Washington in the standings and I’m almost serene about the whole thing. In dreams, right?

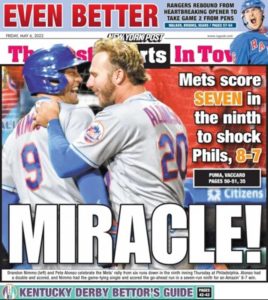

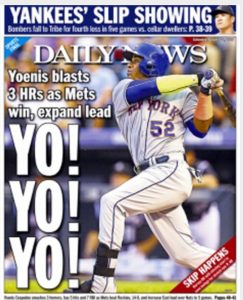

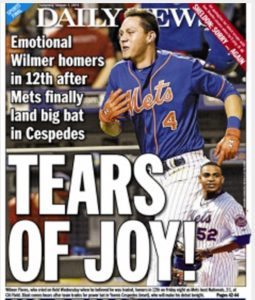

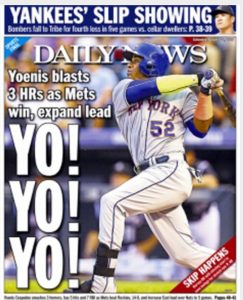

JULY 31: If I weren’t already seated while I’m entering this into my dream journal, I’d suggest I sit down for this. Shoot, maybe I’ll just stand up. Lemme see…the dream starts with a trade. At like a few minutes to four, right before the deadline, I dreamed the Mets got Yoenis Cespedes from the Tigers (wasn’t he with the A’s?). I’m excited, everybody’s excited. Then we’re playing the Nationals, which is a big deal because they’re in first place and we’re in second place, which is one of those things I’m still getting used to in my dreamscape after a real life in which they’ve won the division three times in the past five years and we’ve finished far from it. Matt Harvey is pitching for us. He pitches against them a lot in these dreams, doesn’t he? He’s going really well, but the Met who’s getting everybody’s attention at Citi Field is Wilmer Flores. Nobody’s trading him. They continue to applaud him. We go to extra innings and it’s Wilmer who hits the game-winning home run. Definitely a dream scenario.

AUGUST 2: One more Mets-Nationals dream. This time it’s Sunday Night Baseball, which is usually akin to a nightmare, but crazily enough, the Mets can’t stop hitting home runs, at least in the third inning. Granderson — home run! Murphy — home run! Duda — home run! The Thor guy goes eight. Tyler Clippard, who my subconscious vaguely recalls as a Yankee who came out of nowhere to beat us on Sunday Night Baseball a long time ago, gets the save for us. We’re in a “virtual tie” for first. I’m beginning to wish I was awake for more of this. AUGUST 2: One more Mets-Nationals dream. This time it’s Sunday Night Baseball, which is usually akin to a nightmare, but crazily enough, the Mets can’t stop hitting home runs, at least in the third inning. Granderson — home run! Murphy — home run! Duda — home run! The Thor guy goes eight. Tyler Clippard, who my subconscious vaguely recalls as a Yankee who came out of nowhere to beat us on Sunday Night Baseball a long time ago, gets the save for us. We’re in a “virtual tie” for first. I’m beginning to wish I was awake for more of this.

AUGUST 3: The Mets go to Miami and stomp all over the Marlins while the Nationals lose and we’re alone in first place. Don’t wake me.

AUGUST 8: That guy from California shows up again. It’s his birthday, and I’m taking him to lunch (we’re eating in this place that is showing the night before’s Mets win), then on the subway up to the site of the Polo Grounds to show him around because Willie Mays is his all-time favorite player. I’m telling him I kind of know where I’m going — though I admit I got lost the last time I came here the month before — and eventually, we wander around enough so I get my bearings and I can show him the rededicated John T. Brush Stairway and then the street where Willie used to play stickball. We part ways at Penn Station. The dream includes him telling me he got a parking ticket at the LIRR station near where he’s been staying.

AUGUST 11: I’m wandering around Citi Field before another Mets win (they’re all Mets wins lately) and somebody hands me a flier for Slomin’s Home Heating Oil. Am I dreaming that winter is coming before I know it?

AUGUST 12: For this dream, I’m in the Promenade with a few people I’ve either known well in my past or known a little, but we’re a group tonight and the Mets are winning and Citi Field is noisy like I’ve never heard it for just another weeknight game. I must really want the Mets to be as good as I’m dreaming they are.

AUGUST 14: Once more with the California guy. He tells me he won some kind of special pass to get us (which includes yet another California guy, somebody I’ve never seen before and will never see again) on the field pregame. Curtis Granderson walks by signing autographs for everybody. Michael Conforto comes out and poses for a picture with the California guys, with the one I know wearing a t-shirt with Conforto’s name and number on it. My California friend tells me he never wears that kind of shirt, but he was kind of stoked about the rookie, and this happens. There’s a lot of “this happens” in these dreams I’ve been having in 2015. The game, against the Pirates, gets to the ninth inning tied, and with two out, the same Michael Conforto blasts a fly ball to deep left field that we think is going out, but it doesn’t. We lose in ten. Somewhere in the middle of all this, I buy each of us (me and the California guys, but not the actual Conforto) a tall can of Heineken to show my appreciation for the invitation. I realize I drink very little beer when I’m actually awake, because in the dream I’m shocked at how much beer costs, at least at the ballpark.

AUGUST 19: It’s early evening, and I’m driving home from picking up dinner for my wife and me at a local Italian place, when my cell phone rings. I never talk on the phone in my car, since it’s an old car and a relatively old phone, but I glance and see it’s my father’s girlfriend’s daughter. I answer. She tells me my father is back in the hospital. This dream again. I go home, drop the food off, and my wife and I drive to the hospital, nervously and anxiously, if that makes sense. This time my father has a really bad cough to go with whatever else is bothering him, something like pneumonia. We stay with him for several hours until after he’s checked in. I slip away at one point to a lounge where the Mets are playing the Orioles. Carlos Torres gives up a game-winning home run. We get home very late and heat up some of the Italian food.

AUGUST 21: I visit my dad and watch preseason football with him while trying to keep up with the Mets on one device or another. In the dream, he sort of notices that my attention is divided and I try to play it off like, no, not really, but he knows. Cespedes, who we got a few weeks ago, goes crazy at Colorado, where it’s easy to go crazy. The Mets win, 14-9, which I somehow know they’ve never done before.

AUGUST 22: It’s the next night, and the Mets have beaten the Rockies again by THE EXACT SAME SCORE of 14-9, which must mean I’m dreaming in a loop. AUGUST 22: It’s the next night, and the Mets have beaten the Rockies again by THE EXACT SAME SCORE of 14-9, which must mean I’m dreaming in a loop.

AUGUST 24: A funny thing is happening in these dreams: my father is taking an interest in the Mets a little bit. He truly hasn’t cared what they’ve been up to since my mother died in 1990. But he’s noticed that I show up and stick around if the Mets game is on. I doubt I wouldn’t stick around if we watched something else, but I’m not gonna argue with a hospital patient, so we put the game on. And what a game I dreamed up for this night: David Wright is suddenly playing for the Mets again! And he hits a home run his first time up! Everybody hits a home run for the Mets, it seems. They hit a team-record eight and beat the Phillies, 16-7 (another new score), in Philadelphia. To prove it’s a dream, even the Phillies fans applaud David Wright for coming back with a bang. To prove my dreams are getting even weirder, I don’t see Wright’s home run the instant it’s hit because I’m emptying my father’s bedside urinal for him. It’s only when I return from disposing what needs to be disposed that I notice Wright is accepting his teammates’ congratulations. A surreal tradeoff for having David back and watching with my dad. I’ll take it.

AUGUST 25: Tonight’s twist: somebody comes to my father’s room and tells him he has to get something scanned. He’s against this. Even in my dreams, I don’t know how he puts up with the poking and prodding that I suppose is necessary. While he protests that he won’t go, I come up with the craziest thing I’ve ever said, awake or asleep. “Dad, if you don’t get better, you can’t go home, and if you can’t go home, I can’t come over to watch the World Series with you.” It seems he’s been aware of how well the Mets are doing and he’s already skipped ahead to October. HE’S the one who mentioned the World Series to ME — in AUGUST. I don’t know where I got the nerve to dictate terms to him and throw in baseball, but son of a gun (was that Freudian?), it worked. He puts up with the scan. Hopefully it’s all part of getting better.

AUGUST 27: There’s a play in tonight’s game nobody could have dreamed up: Jeff Francoeur (the Met from 2010 who I’m now dreaming plays for the Phillies) lines a ball off Carlos Torres’s foot, and Daniel Murphy retrieves it and flips it to Torres without looking, trusting Torres is covering first, and he is, and Francoeur is out. I’m dreaming I’m watching in my dad’s hospital room and Gary Cohen calls it “a play you’ve never seen before and you may never see again.” Even if it’s just in my subconscious, it’s incredible. Next thing I know, I’m driving home on a deserted road, the Mets win in thirteen and I applaud at the wheel and I can hear the echo come back to me through my car window.

AUGUST 28: The phone rings on a Friday afternoon. It’s my dad. He wants to make sure I’m coming up to watch that night’s game with him. That’s never happened before in my dreams or in my life.

AUGUST 29: I find the time in my dreams to head back to Citi Field. They’re giving away Jesse Orosco bobbleheads and playing the Red Sox. Now tell me who’s skipping ahead. There’s an insanely long line to be one of the first how-many thousand. Of course there is. My Met dreams are insanity practically every night.

SEPTEMBER 2: Ruben Tejada hits an inside-the-park home run, because what else HAVEN’T I dreamed this year?

SEPTEMBER 4: Matt Harvey’s agent says Matt won’t pitch in the playoffs if he’s exceeded his post-surgery innings limit. Didn’t they pull the same thing with Strasburg and the Nationals? Why would this filter into my subconscious? Why I am already deep-down dreading something going wrong in the postseason? Can’t I have a clear head for all of this?

SEPTEMBER 5: Watching the Mets with my father again, and Bartolo Colon is pitching at Miami. He throws a guy out at first by tossing the ball behind his back. I guess this qualifies as clearing my head.

SEPTEMBER 7: The Mets are playing a huge Labor Day game at Washington. We’re still in first place, but this is the Nationals’ big chance. Yet we win. I’m glad my subconscious hasn’t lost the pennant race thread.

SEPTEMBER 8: The Mets are still in Washington, and Harvey is getting lit up, but the Mets come from way behind and win again. In the parking lot at the hospital, where I’ve been watching in this dream, I let out a howl at the moon. That has to be symbolic of something.

SEPTEMBER 9: Last game in Washington. Kelly Johnson hits a late home run. Yoenis Cepedes hits a later home run (he hits a lot of them). The Mets sweep the Nationals and, in my dreams, they’ve all but clinched the division and made the ghosts of 2007 go away. It’s not too early in September for that, I hope.

SEPTEMBER 13: I’m home watching a Mets game on a Sunday afternoon from Turner Field, so I’d expect something terrible to happen. Indeed, in my dream, the Mets are losing by three runs with two out in the ninth, but then Daniel Murphy hits a three-run homer and Gary Cohen says the Mets don’t know how to lose. In point of fact, they win in the tenth inning, and I can’t imagine I’ll be any happier the rest of the season. Then the phone rings, and it’s my sister, who’s visiting my father, telling me Dad wants to know when I’ll be there, so I leave and drive up, and the postgame show on the radio ends, and there’s no Mets in the car, then no Mets at the hospital, and he’s in a bad mood (I can’t blame him) and I can’t even get him interested in the Giants and Cowboys on Sunday Night Football, and I leave feeling a little miserable about everything. I’ve really got to learn to wake up at the peak of these dreams.

SEPTEMBER 25: Most of the family is together in the hospital room this afternoon. Dad and his girlfriend are cheerful at first. They’re both aware the Mets have a dwindling magic number and tell me they’re happy for me. Then a doctor with not much of a bedside manner comes in to tell us the next step is palliative care. Dad tries to wrap his head around this. And, for reasons unknown to me, on TV they’re talking about the Pope visiting Philadelphia (the Mets are in Cincinnati).

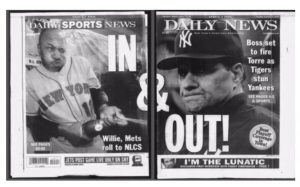

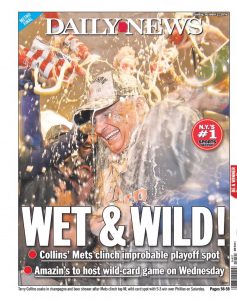

SEPTEMBER 26: The Mets have clinched their first division title since 2006. I couldn’t have dreamed this at the outset of April. I’m watching it at home, I’m going out to bring back pizza, I’m opening Champagne, I’m toasting with my wife. Nothing is going to ruin this for me.

SEPTEMBER 27: My wife and I visit my dad. He’s in the ICU all of a sudden. He’s only vaguely aware of the Mets being division champions and drifts off a lot. The dream ends with us sitting around his bed watching 60 Minutes. SEPTEMBER 27: My wife and I visit my dad. He’s in the ICU all of a sudden. He’s only vaguely aware of the Mets being division champions and drifts off a lot. The dream ends with us sitting around his bed watching 60 Minutes.

OCTOBER 4: Dad has moved into a new facility, in line with the palliative care, and I’m at Citi Field for the final game of the season. Even in my dreams I go to Closing Day. The Mets win their 90th game (didn’t Sandy Alderson say that’s what this perennially sub-.500 team was going to do back in Spring Training, before I found it so difficult to stay awake?) and David Wright addresses the crowd, which seems unusual, but whatever. Also, we were apparently no-hit again the night before. Bring it on, subconscious. We’ve got playoffs, I think.

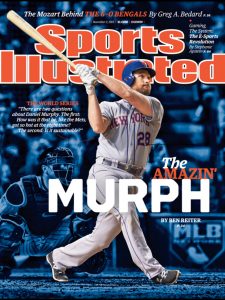

OCTOBER 9: We do have playoffs, Mets at Los Angeles. We win Game One. Daniel Murphy hits a home run off Clayton Kershaw, burning his name from his bat into the ball. Jacob deGrom strikes out 13. Such specificity. Also, deGrom plays a prank on Murphy during the postgame press conference, lowering his chair.

OCTOBER 10: Chase Utley, who is mysteriously a Dodger now, breaks Ruben Tejada’s leg by sliding into second base. Now I’m experiencing revenge dreams within my dreams at Utley’s expense. Mets lose.

OCTOBER 12: In what may be the weirdest dream of 2015 to date (and that’s saying something), I’m at Citi Field for the third game of the National League Division Series. Six seasons of Citi Field before this one, and I’ve never imagined, let alone dreamed, this place that so isn’t Shea Stadium, would either host one of these or get revved up for one of these. But, brother, is it ever. We’ve been waiting a long time to get loud, so it’s very loud — especially when Utley comes out as part of the introductions (we’ve all had revenge dreams) and then when Tejada comes out with the aid of cane festooned with Met logos. Best part of the dream is Cespedes hits a monster home run, the Mets win by a lot with Harvey pitching despite his agent’s protestations, and they’re one game from taking the series.

OCTOBER 13: The Mets are still one game from taking the series, since Clayton Kershaw beats them in this edition of my playoff dreams. Daniel Murphy hits another home run, though. And, oh, I’m there, like going to Citi Field for playoff games is now something I do.

OCTOBER 14: Guess which venue just showed up in my dreams again. Nope, not Citi Field — the Beacon Theatre. Am I looking for a beacon of light to guide the Mets safely to victory tomorrow night? For the record, I’m at a Steely Dan concert, and when they get to the part of “My Old School” that goes “California/tumbles into the sea…” I (in my Mets jacket) cheer, and I’m pretty sure I’m not the only one.

OCTOBER 15: I’m at the new place, with my dad. Whether the Mets advance in the postseason is at stake, and I’m watching on a palliative care facility TV. Not how I pictured it in my dreams, but that’ll show you what dreams know. The Mets are in trouble early. I must be having REM cycle problems sleeping. But Terry Collins stays with Jacob deGrom, Jacob deGrom hangs tough, Daniel Murphy both homers and does goofy stuff on the bases (that pays off) and, with some help from Syndergaard in relief, then Familia, we win. I mean, we win! I don’t know if I should shout too loud in this dream, given that there are probably a few older folks trying to sleep. Ah, what the hell — YIPPEE!!

OCTOBER 16: I dream there’s a picture going around the Internet of two Mets fans, one who was on the front page of the Daily News after the collapse of 2007, and one of another who was on the front page a year later after the collapse of 2008. They were both at Dodger Stadium looking really happy. Maybe my subconscious is no longer haunted by bad endings and Shea Stadium.

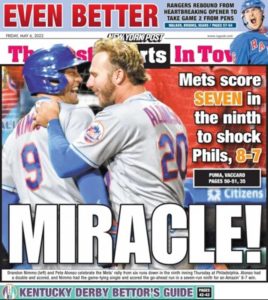

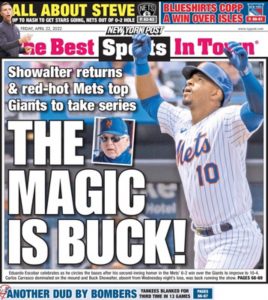

OCTOBER 17: Instead of being haunted by Shea, I am haunting Citi, site of Game One of the NLCS, Mets versus Cubs. How odd that it’s the Cubs in my dream. The Mets trying to catch the Cubs is where it all started for me as a fan, spurred on by my reading the Post my father would bring home every night. I’d see the standings and I’d see a cartoon on the back page, where the Cubs were the bear and the Mets were a bird of some sort, and now this? Does it mean some kind of full-circle in my relationship with my dad? While I ponder that, I note that my first NLCS game since 2006 (the Mets’ too, I guess) goes swimmingly. Murphy keeps hitting homers and we win. OCTOBER 17: Instead of being haunted by Shea, I am haunting Citi, site of Game One of the NLCS, Mets versus Cubs. How odd that it’s the Cubs in my dream. The Mets trying to catch the Cubs is where it all started for me as a fan, spurred on by my reading the Post my father would bring home every night. I’d see the standings and I’d see a cartoon on the back page, where the Cubs were the bear and the Mets were a bird of some sort, and now this? Does it mean some kind of full-circle in my relationship with my dad? While I ponder that, I note that my first NLCS game since 2006 (the Mets’ too, I guess) goes swimmingly. Murphy keeps hitting homers and we win.

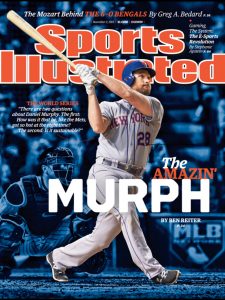

OCTOBER 20: This dream says Game Three, at Wrigley. At the place where my father is hanging out, too. He’s sort of into the game when he’s awake (I should talk — I seem to be mostly into it when I’m asleep). The Mets take a three-oh series lead. Did I mention Murphy hit ANOTHER home run? And that the announcers in my dream said he hit one in Game Two? I don’t remember Daniel Murphy being this much of a power hitter.

OCTOBER 21: I’ve never seen all of Back to the Future II, but in my dream, it’s significant that this is October 21, 2015, because apparently the Cubs win the World Series on this date in, you know, the future. (In, you know, the movie.) But never mind the movies. Let’s screen what I’ve been dreaming: the Mets win the pennant! Yes, Murphy has hit a home run in his sixth consecutive dream…I mean game. And though I’m watching from home, I get to share it with my father, as he calls me a few minutes after it happens. The strange part is he’s been calling me at all hours confused about whether it’s day or night, but in this part of the dream, he’s not only totally lucid, but simply calls to congratulate me, like he knows this is important to me, and that it was important to him to let me know that. OCTOBER 21: I’ve never seen all of Back to the Future II, but in my dream, it’s significant that this is October 21, 2015, because apparently the Cubs win the World Series on this date in, you know, the future. (In, you know, the movie.) But never mind the movies. Let’s screen what I’ve been dreaming: the Mets win the pennant! Yes, Murphy has hit a home run in his sixth consecutive dream…I mean game. And though I’m watching from home, I get to share it with my father, as he calls me a few minutes after it happens. The strange part is he’s been calling me at all hours confused about whether it’s day or night, but in this part of the dream, he’s not only totally lucid, but simply calls to congratulate me, like he knows this is important to me, and that it was important to him to let me know that.

OCTOBER 25: I’m going up to my father’s place with a bag from Burger King. In my dream, my sister told me I should bring him a couple of cheeseburgers, that he likes Burger King cheeseburgers. I’ve avoided Burger King and its Golden Arched-brethren for years, but in my dream I go to the drive through and order some cheeseburgers. On my way up there, I notice Mets flags flying in people’s front yards. There’s something different in the air, and it’s not just the Burger King aroma. There’s no ballgame on, so it’s not much of a visit, and he’s not that into the cheeseburger. On my way home, my car is making a noise. I barely steer it into the parking lot. My driving has improved throughout these dreams, probably out of necessity. But it’s still an old car, just like my dad is an old dad. I eat the leftover cheeseburger. It doesn’t sit well. OCTOBER 25: I’m going up to my father’s place with a bag from Burger King. In my dream, my sister told me I should bring him a couple of cheeseburgers, that he likes Burger King cheeseburgers. I’ve avoided Burger King and its Golden Arched-brethren for years, but in my dream I go to the drive through and order some cheeseburgers. On my way up there, I notice Mets flags flying in people’s front yards. There’s something different in the air, and it’s not just the Burger King aroma. There’s no ballgame on, so it’s not much of a visit, and he’s not that into the cheeseburger. On my way home, my car is making a noise. I barely steer it into the parking lot. My driving has improved throughout these dreams, probably out of necessity. But it’s still an old car, just like my dad is an old dad. I eat the leftover cheeseburger. It doesn’t sit well.

OCTOBER 26: I call my mechanic in my dream and he wants to talk baseball, which I should relish, since he’s a Yankees fan and I’ve got a team in the World Series, but I get to the point, that my car has been making a noise and then some. Next thing I dream, it’s towed to his garage and I get a call that it’s the transmission, and he’s talking about me letting go of it, but with the Mets going to the World Series and me somehow making good on my word to my dad that I’m going to watch it with him (even if he’s not home, exactly), I’m not up for letting go of longstanding attachments. It’s going to cost a stupid amount of money, but I say go ahead, fix it.

OCTOBER 27-28: In my dream, I’m still without my car, so I have to take the Long Island Rail Road in several different directions to get to my dad’s. Not how I would have pictured watching the Mets in their first World Series in fifteen years, but I make it. We’re on the road playing Kansas City, a team I liked in that American League way when I was a kid, but now they’re my nemesis. Game One doesn’t go well. There’s an inside-the-parker from the Royals’ leadoff hitter, not a good sign. Something’ weird with the TV feed, which isn’t helping my father’s concentration. Fortunately it comes back, as do the Mets. It’s 3-3 in the eighth when the Royals’ first baseman, who has the same name as one of my cats, makes an error and we take the lead. Maybe I’m dreaming of Buckner and 1986, when my parents were as into the Mets as I was (but what New Yorker wasn’t?). Any chance this was gonna be a good dream goes out the window when Jeurys Familia gives up a ninth-inning home run, and it’s tied, and the night goes on and on and we lose in the fourteenth and I have to take an expensive cab ride home well after midnight.

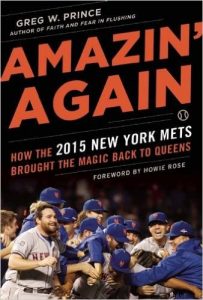

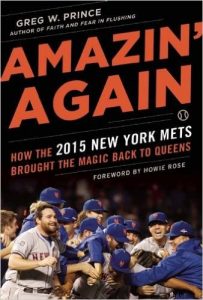

OCTOBER 30: The Mets are down oh-two in the Series, but I’m not giving up, because, according to the latest tributary of my dreamscape, I’m writing a book about the 2015 Mets, but it will only be published if they win. I’m working furiously on it before Game Three so I can have some of the chapters done and THEN walk to the train station and head for MY FIRST WORLD SERIES GAME. Not even in my dreams did I see the Mets in person in the Series in 1969, 1973, 1986 or 2000, but here I am, coming down the staircase from the 7 and taking in all the World Seriesness of it. I see a number of friends in the parking lot beforehand, including the California guy. It’s like we’re all getting our reward for our patience, and it makes me feel really good. Between one of the innings, they tell us to hold up our Stand Up 2 Cancer cards, which I do. I’ve written my father’s name on it. Daniel Murphy doesn’t hit a home run, but David Wright does. So does Curtis Granderson, but I don’t see it, because in this dream, the whole thing is almost too much and I have to get up and do a lap around Field Level. What else happened? Oh, Syndergaard! He’s brushed back that pesky leadoff Royals hitter, which was a welcome sight. Thor pitched well and we scored a lot and we won! I’ve seen the Mets win a World Series game in my dreams! Close enough to reality, I figure. OCTOBER 30: The Mets are down oh-two in the Series, but I’m not giving up, because, according to the latest tributary of my dreamscape, I’m writing a book about the 2015 Mets, but it will only be published if they win. I’m working furiously on it before Game Three so I can have some of the chapters done and THEN walk to the train station and head for MY FIRST WORLD SERIES GAME. Not even in my dreams did I see the Mets in person in the Series in 1969, 1973, 1986 or 2000, but here I am, coming down the staircase from the 7 and taking in all the World Seriesness of it. I see a number of friends in the parking lot beforehand, including the California guy. It’s like we’re all getting our reward for our patience, and it makes me feel really good. Between one of the innings, they tell us to hold up our Stand Up 2 Cancer cards, which I do. I’ve written my father’s name on it. Daniel Murphy doesn’t hit a home run, but David Wright does. So does Curtis Granderson, but I don’t see it, because in this dream, the whole thing is almost too much and I have to get up and do a lap around Field Level. What else happened? Oh, Syndergaard! He’s brushed back that pesky leadoff Royals hitter, which was a welcome sight. Thor pitched well and we scored a lot and we won! I’ve seen the Mets win a World Series game in my dreams! Close enough to reality, I figure.

OCTOBER 31: I’m back at Citi Field. I’m meeting up with people who have the tickets for Game Four. I see Bartolo Colon through a glass door. Someone in my dream yells BIG SEXY! at him and Colon waves without looking up. It’s Halloween, and people have come to the ballgame in costume. I run into a father and son who tell me they’re the ghosts of World Series past, dressed as “1969” and “1986”. I miss another home run, this one by Conforto, because I got up to go the bathroom and then opted for a slice of overpriced pizza (shortest line), but Conforto hits two, and I see the second. Unfortunately, all the nice dreams I’ve been having seem to catch up with me. Daniel Murphy, who’s on the cover of Sports Illustrated (cursed?) is no longer hitting, but he does make a crucial error. Cespedes gets himself doubled off base, too. The Mets lose and are one game from elimination. I just stand around a while as the ballpark empties out. It can be very lonely in my dreams.

NOVEMBER 1-2: I never dreamed of the Mets playing in November, but here they are, trying to not lose the World Series, no matter what the calendar says. My car’s still in the shop. so I’m commuting by rail to get to my father’s. Matt Harvey is pitching really well. Granderson homers. Dad naps in and out of the action. It’s actually going pretty fast. Maybe I can make a decent-hour LIRR and wind my way home and then we can plan for Game Six. Maybe I shouldn’t have been thinking about such things prematurely because suddenly Harvey is on the mound in the ninth after yelling at Terry Collins in the dugout (I think he was gonna be taken out) and this long, painful drip of a Royals rally ensues. I’m not sure of the details. I may have blocked them out, but I do know it’s tied and we’re in extra innings again, and my father’s asleep and I’m texting with my sister which is REALLY weird, because she’s never cared about baseball, but in my mind in my dream I’m remembering my very first World Series memory: me and her running errands with Dad with Game One against the Orioles on the radio for my benefit. Don Buford homers off Tom Seaver, but Dad tells me it’s all right, there’s still a long way to go. We lose that game, but we win that Series. It, like the business about the Post and the standings and the cartoon, is the touchstone of my fandom. Full-circle? Going in circles? Why would my sister be watching the World Series? Not to see the Mets win, apparently. I dream the Royals score a ton of runs, again via details I block out, and Wilmer Flores, who everybody embraced back in July, takes strike three to end it. My father is awake by now and offers some condolences blended with some encouragement. He’s lying there in bed, unable to get up and walk out as I’m sure he’d prefer, and he’s telling me everything’s gonna be all right, just like in the Chrysler in 1969. I think I tell him I was glad to watch so much baseball with him. Or did I forget to mention that? I should’ve said something profound, but we’ve never talked to each other like that, so why make him uncomfortable with emotions? I don’t know. I have to take another expensive cab ride home, during which me and the driver end up talking about Carmelo Anthony for some reason. Then, in the dream, I get home, I write a whole lot about how much this weird dream of a season meant to me, I fall asleep (sleeping while I’m sleeping; I can’t make sense of anything anymore), and when I wake up, I learn my car is fixed, so I better pick it up, and they’re gonna publish my book despite the Mets losing, so I better finish it. NOVEMBER 1-2: I never dreamed of the Mets playing in November, but here they are, trying to not lose the World Series, no matter what the calendar says. My car’s still in the shop. so I’m commuting by rail to get to my father’s. Matt Harvey is pitching really well. Granderson homers. Dad naps in and out of the action. It’s actually going pretty fast. Maybe I can make a decent-hour LIRR and wind my way home and then we can plan for Game Six. Maybe I shouldn’t have been thinking about such things prematurely because suddenly Harvey is on the mound in the ninth after yelling at Terry Collins in the dugout (I think he was gonna be taken out) and this long, painful drip of a Royals rally ensues. I’m not sure of the details. I may have blocked them out, but I do know it’s tied and we’re in extra innings again, and my father’s asleep and I’m texting with my sister which is REALLY weird, because she’s never cared about baseball, but in my mind in my dream I’m remembering my very first World Series memory: me and her running errands with Dad with Game One against the Orioles on the radio for my benefit. Don Buford homers off Tom Seaver, but Dad tells me it’s all right, there’s still a long way to go. We lose that game, but we win that Series. It, like the business about the Post and the standings and the cartoon, is the touchstone of my fandom. Full-circle? Going in circles? Why would my sister be watching the World Series? Not to see the Mets win, apparently. I dream the Royals score a ton of runs, again via details I block out, and Wilmer Flores, who everybody embraced back in July, takes strike three to end it. My father is awake by now and offers some condolences blended with some encouragement. He’s lying there in bed, unable to get up and walk out as I’m sure he’d prefer, and he’s telling me everything’s gonna be all right, just like in the Chrysler in 1969. I think I tell him I was glad to watch so much baseball with him. Or did I forget to mention that? I should’ve said something profound, but we’ve never talked to each other like that, so why make him uncomfortable with emotions? I don’t know. I have to take another expensive cab ride home, during which me and the driver end up talking about Carmelo Anthony for some reason. Then, in the dream, I get home, I write a whole lot about how much this weird dream of a season meant to me, I fall asleep (sleeping while I’m sleeping; I can’t make sense of anything anymore), and when I wake up, I learn my car is fixed, so I better pick it up, and they’re gonna publish my book despite the Mets losing, so I better finish it.

That was the last entry. Everything must have returned to some semblance of normal after that. I don’t think I’ve experienced anything remotely like all of that since then, in my dreams or wide awake.

PREVIOUS ‘MY FAVORITE SEASONS’ INSTALLMENTS

Nos. 55-44: Lousy Seasons, Redeeming Features

Nos. 43-34: Lookin’ for the Lights (That Silver Lining)

Nos. 33-23: In the Middling Years

Nos. 22-21: Affection in Anonymity

No. 20: No Shirt, Sherlock

No. 19: Not So Heavy Next Time

No. 18: Honorably Discharged

No. 17: Taken Down in Paradise City

No. 16: Thin Degree of Separation

No. 15: We Good?

No. 14: This Thing Is On

No. 13: One of Those Teams

by Greg Prince on 22 March 2024 3:30 pm One of the core tenets to emerge amid the MY FAVORITE SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT countdown is that the bromide “it’s not where you start, it’s where you finish” lacks foolproofitude. Sometimes the best part of a season is the start. Sometimes it’s somewhere in the middle. Sometimes it’s in the anticipation, like when you learn about a big-name signing to fill a gaping void on the eve of the next season, though what you’d really like is some follow-through once that season gets underway. If you’re extremely lucky, it is indeed where you finish, though you may have caught on that the Mets haven’t been extremely lucky all that often in this century.

Sometimes it’s where you spend the bulk of the regular season, the end of the regular season, a good bit of the postseason, and — if your head takes you there — the succeeding offseason. Sometimes, a fan makes the most of everything good that comes his way and learns to step around the unavoidable not-so-good. The not-so-good is always going to be unavoidable, but trust me: you can map out a detour.

***13. 2006

It’s January of 2024. My wife and I are watching the NFC Championship Game, the Lions at the 49ers, actually into it rather than simply having it on in the background while we scroll away on our devices. Every year at this time, bereft of baseball for months, I care more about football than I’d have suspected the previous summer. Stephanie thinks football looks good on TV and is capable of dipping into its spectacle on any given Sunday, especially if the HD picture is enhanced with a compelling storyline. This January, we have a doozy. Like all non-gambling Americans who are ostensibly unaffiliated in this matchup, we are Lions fans for the duration. Nothing against the Niners, but how can you NOT root for the team that has NEVER been to any of the previous LVII Super Bowls when they have an honest-to-goodness opportunity to make it to Super Bowl LVIII?

The Lions roar to a 24-7 lead and we offer sincere huzzahs for their (alas temporary) good fortune. We express genuine excitment for Michiganders we’ve never met. We don’t know any longtime, hardcore Lions fans, but today we are their auxiliary cheering section. Warming to the theme of the evening, we soon find ourselves sorting through teams that have waited so, so long to win the big one. In football, this automatically means the Lions and the Browns, two venerable franchises that have been on the clock ever since the 1970 NFL-AFL merger. No Supe for Detroit, ever; they haven’t gotten even this far since January of 1992, when Stephanie and I had been married precisely nine weeks. No Supe for Cleveland, ever…unless you count the Browns that became the Ravens…which, of course, you don’t. The last Browns team to win a National Football League championshp did so when I was turning two and Stephanie was, shall we say, not quite minus-three.

They Lions and the Browns, however, are hardly alone in Roger Goodell’s antsy waiting room. The Arizona Cardinals snuck into one Super Bowl, lost it late, and have to reach back to their Chicago incarnation and 1947 for their most recent NFL championship. The Atlanta Falcons have been been in the Super Bowl twice, led one of them by 25 points, yet have nothing in the way of an ultimate reward to show for their 1966 hatching. The Jets — for whom my “I’m more of a Giants fan, but I root for them, too” affinity has been on pause after sitting through a rain-soaked intraswamp debacle at the end of October — have gone cold for 55 years. The Dolphins, whose dynasty briefly captured my youthful fancy, just passed the half-century mark without augmenting their pair of Vince Lombardi trophies and are now four decades removed from their most recent trip to the Big Game (I can’t say I mind). The Cowboys have retained their glamour but haven’t gotten near a Super Bowl since their last win there XXVIII seasons ago (no complaints here). Washington was considered a jewel franchise, but their last significant celebration came the same January the Princes were newlyweds and the Lions last peaked. The then-Skins beat the Buffalo Bills to win it all that Sunday; the Bills are their own star-crossed story. As are, with less fanfare, the Bengals. And the Chargers. And the Vikings. And whatever happened to the Raiders? Didn’t they used to be an avatar of excellence? And didn’t they used to play in California?

These “haven’t since…” or “have never” totals can sneak up on fans and impartial observers alike. They can also disappear in a flash. Chiefs fans waited 50 years to re-enter the Kingdom of champions. Taylor Swift issues aside, when was the last time you conjured deep empathy for their cause? Hell, the Patriots, mostly futile from their founding in 1960 until a former Montreal Expos draft pick trotted into the huddle to relieve Drew Bledsoe in 2001, once presented a sympathetic face to the sporting world.

Natch, even before the Niners rally to ruin the Lions’ bid to cement their status as America’s Adopted Team (and two weeks before San Francisco guarantees it will extend its stealth Super Bowl championship drought to three decades), the conversation in our living room shifts to baseball. I am moved to catalogue the contact buzzes I’ve allowed myself as one overlong championship dearth of 40 or more years after another fell by the wayside ater the turn of the millennium: the Angels in 2002 (Stephanie joined me on that bandwagon, purchasing a few off-brand Rally Monkeys at our neighborhood Pathmark to send the Halos good vibes), the Red Sox in 2004, the White Sox in 2005, the Giants in 2010, the Cubs in 2016, and, to a lesser extent, the Astros in 2017 (extent lessened because of what came to light regarding their methods a couple of years later) and the Rangers in 2023 (I was rooting for the Diamondbacks, but it was still cool to see loyal Arlingtonians sip from their first goblet of glory after 52 seasons of building up a thirst). All this talk got me estimating how long is too long; when a wait becomes a drought; and when your team unquestionably becomes One of Those Teams everybody knows has been on the outside looking in forever.

Like the Lions, whose last NFL championship occurred in 1957.

Like the Browns, winners of it all most recently in 1964.

Like the Jets, I suppose. I’m just old enough to vaguely recall their standing as defending Super Bowl champions, but “January 12, 1969,” serves as much as a cudgel for the cruel these days as it does a milestone for the faithful, like “1940” did for hockey’s Rangers until 1994 (which wasn’t as long as it’s been for the Jets).

Like the Indians/Guardians, whose fans had to keep suffering toward and eventually past a seventh decade in order for the burden to be lifted from the shoulders of Cubs-lovers after 108 years.

Of course this led me to the Mets and how the 17 years between 1969 and 1986 represented a personal eternity, given that I waited between the ages of 6 and 23 for the second world championship. That’s being in first grade for the first one and being out of college a year-and-a-half by the second one. Even the wait between World Series appearances, from ’73 to ’86 was endless at that stage of my existence.

Thing is, I continued, every year without a championship is one year too many, but you have to be reasonable about it. Yeah, it sucked immensely to not win again in 1987, having now had a fresh taste of the top and then been denied an immediate next helping, but that was just one year. Boo-hoo, I’ve gone nearly 365 days without a ticker-tape parade. I could have made similar rationales to myself during the near misses and close calls that followed in ’88, ’89 and ’90 had I not been so aggravated by the near misses and close calls that followed in ’88, ’89 and ’90. It wasn’t until October 27, 1991, which happened to be the night the Twins and Braves were playing Game Seven of their World Series, that I really developed an inkling that length was coming into play. It was the fifth anniversary of our Game Seven victory, the one that vaulted 1986 onto the plane it shared with 1969 and no other Mets team. The Channel 4 news showed a clip of Jesse Orosco striking out Marty Barrett to commemorate the milestone. I was already aware of what date it was and what had happened five years ago tonight and what hadn’t happened since. Now it was This Date In History. For the first time since October 27, 1986, that world championship plane of ours was beginning to feel overly underoccupied.

I drifted from the Lions and Niners in front of us and heard myself reflecting aloud. I got older, I told Stephanie, and I waited for the Mets to make it back to the World Series. That took until 2000. Fourteen years, a pretty arid dry spell, I said. Stephanie nodded. She was there. She remembered. It was great to get where we got, but we didn’t win what there was to win, and the wait just kept getting longer. We passed 2003 emptyhanded, I added, noting that meant we would mathematically exceed those 17 years that spanned ’69 to ’86, and the next time we got to the World Series, in 2015 (also great), it was nearly 30 years — and when we didn’t win that one, it grew to exactly 30 years. It’s only grown longer since then.

The time I really thought we’d get it done, though, the time I decided was going to be perfect to get it done, I Metsplained to my wife (for not the first time, but she’s a good audience for reruns), the wait had already been long, but not as long as it would become. Not necessarily too long — not if it was going to come to an abrupt end, which I really and truly believed it would. The wait, at that point, was a 20-year wait. I was very ready for it to end after 20 years. So very ready. It should have. Twenty years was long enough.

But it didn’t end that year. It just kept going. It’s still going.

I started to detail why it should have happened for us that season and postseason, but I couldn’t quite get more than few words out without something get caught in my throat and something else welling up in my eyes. Stephanie understood. She was there then, too; she’s been with me a lot of seasons. I went silent for a moment, as if listening to the football play-by-play demanded my utmost attention. At last, I steered the subject into the long-term parking garage.

“Anyway, you don’t want to be One of Those Teams.”

Had the New York Mets won the World Series in 2006 and not again as of the Spring of 2024, it would be too long. Definitely too long. Longer than 1969 to 1986. But it wouldn’t be nearly as long as it is now, and the thought of the Mets being One of Those Teams wouldn’t have crossed my mind during the most recent NFC Championship Game or any time. That topic would be fodder for the Guardians fans (76 years since their last world championship in 1948) and the Pirates fans (45 years since 1979) and the Orioles and Tigers fans (41 and 40 years since 1983 and 1984, respectively) and the thus far altogether unrewarded followers of the Padres (born 1969), Brewers (relocated from Seattle 1970), Mariners (replacing the Pilots in 1977), Rockies (expansion class of 1993) and Rays (close but no cigar twice since swimming into being in 1998) AND it would be for the fans of any ballclub whose last World Series title came anywhere between 1987 and 2005. Our 18-year dry spell wouldn’t speak well for us in 2024, but at least we wouldn’t be wandering through the desert twice as long as we have been since 1986.

And who knows? We win in 2006, maybe we get the hang of it for 2007 and/or 2008. Maybe we stay on a perennial pennant path and don’t recede for eras at a time. Maybe we become One of Those Teams in a totally different sense of the phrase.

But we didn’t. We could have. We should have. We didn’t.

It’s 38 years and counting.

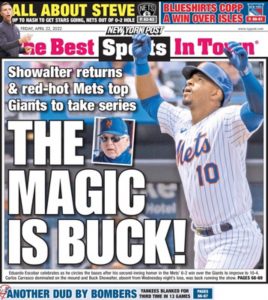

Of every Met year to have transpired after 1986, I’ve been absolutely convinced during only one of them that the Mets of the moment were on the verge of achieving their third world championship. In 2006, I knew as much as fan could think he knows it that THIS would be our year. Maybe not before it started, but before April was over I sensed strongly that we had a real shot. There were moments in May when we/I had to negotiate a pocket of uncertainty, but we/I made it through the month without a fatal stumble, and faster than you might say “hey, did you see where Pat Mahomes’s kid plays quarterback for Kansas City?” we took off and we never looked back. The divisional race was over by the middle of June, with us at the front of it, coasting in the direction of October, now and then revving our motor to demonstrate to any doubters we were capable of doing whatever it took to win whatever there was to win. Of every Met year to have transpired after 1986, I’ve been absolutely convinced during only one of them that the Mets of the moment were on the verge of achieving their third world championship. In 2006, I knew as much as fan could think he knows it that THIS would be our year. Maybe not before it started, but before April was over I sensed strongly that we had a real shot. There were moments in May when we/I had to negotiate a pocket of uncertainty, but we/I made it through the month without a fatal stumble, and faster than you might say “hey, did you see where Pat Mahomes’s kid plays quarterback for Kansas City?” we took off and we never looked back. The divisional race was over by the middle of June, with us at the front of it, coasting in the direction of October, now and then revving our motor to demonstrate to any doubters we were capable of doing whatever it took to win whatever there was to win.

I LOVED living in the heart of 2006. We won on Opening Day (helped by the lack of video replay review on a play at the plate; go tell it to a time machine), lost our second game in irritating fashion (perhaps the gods’ way of imbuing us with humility) and won our third game to take sole possession of first place. It was an item we held for the rest of the year. The Braves, who’d bullied us since suddenly remembering they played in the eastern half of the United States, had at last crumbled. We were five games ahead of them after the twelfth game of the season, and they were done. The Phillies, who annually boasted talent but lacked cohesiveness, could never quite get their act together. They had crept as close to 3½ games behind us as of June 7. By the afternoon we finished a three-game visit to Citizens Bank Park on June 15, we led them, our closest competitors, by 9½. Soon our margin over the pack was double-digits and it never slipped into singles.

For the first time since we’d pulled away from the Pirates in August of 1988, I knew — I mean knew — we were going to win our division. The 2006 Mets were NL East champs-in-waiting for more than half a season. The Wild Card, our treasured prize in 1999 and 2000, was for the rabble to fuss over. We’d effectively clinched first place.

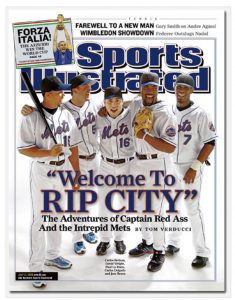

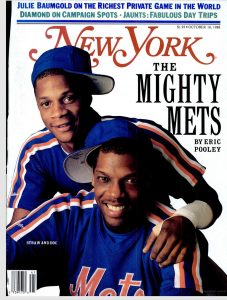

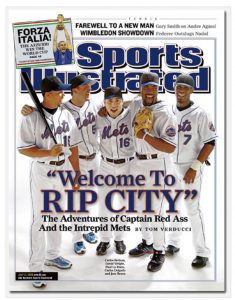

All at once, we were larger than life. It was such a step up from 2005 that I might have asked myself if this wasn’t all happening too soon (especially given that it was the second year of our blog, when I tended to pinch myself that we got to write about this kind of joyride), but then I’d remember twenty years was hardly too soon. So I got back to taking in all our enormity and reveling in it nonstop. Five Mets graced the cover of Sports Illustrated. Six Mets populated the National League All-Stars. Our new television network was a cable TV sensation. Our new ballpark was putting down stakes in Shea’s parking lot. Our Team, Our Time, as our goofy yet zeitgeisty attempt at an anthem put it. When the 1986 Mets swung by Shea in August to celebrate their china anniversary, they could have been forgiven for doing a double-take if they thought they were glimpsing a version of their younger selves. We were in the midst of a seven-game winning streak. We were nursing a 14-game lead. We were days away from swatting dramatic home runs to unnerve the Cardinals. By the end of the month, we’d have the best record in baseball. All at once, we were larger than life. It was such a step up from 2005 that I might have asked myself if this wasn’t all happening too soon (especially given that it was the second year of our blog, when I tended to pinch myself that we got to write about this kind of joyride), but then I’d remember twenty years was hardly too soon. So I got back to taking in all our enormity and reveling in it nonstop. Five Mets graced the cover of Sports Illustrated. Six Mets populated the National League All-Stars. Our new television network was a cable TV sensation. Our new ballpark was putting down stakes in Shea’s parking lot. Our Team, Our Time, as our goofy yet zeitgeisty attempt at an anthem put it. When the 1986 Mets swung by Shea in August to celebrate their china anniversary, they could have been forgiven for doing a double-take if they thought they were glimpsing a version of their younger selves. We were in the midst of a seven-game winning streak. We were nursing a 14-game lead. We were days away from swatting dramatic home runs to unnerve the Cardinals. By the end of the month, we’d have the best record in baseball.

Baseball Like It Oughta Be. Again.

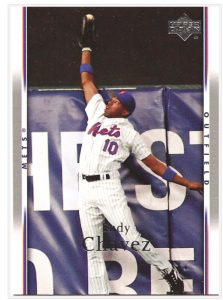

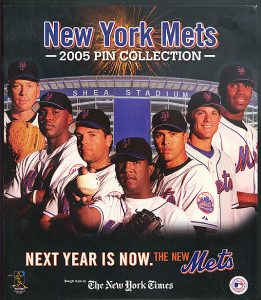

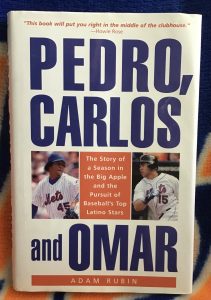

Jose Reyes and David Wright had blossomed into the superstardom that had been projected for them. Paul Lo Duca (Captain Red Ass, per SI) made us more or less forget Mike Piazza was still active and playing for somebody else. Carlos Beltran shook off his first-year New York tentativeness and put up MVP numbers. Carlos Delgado represented more of a good Carlos thing; between them, Belgado stroked 79 homers and drove in 230 runs. ¡Dos Carloses son mejores quen uno! Nobody saw Jose Valentin coming, yet he was hitting home runs regularly and filling the gap that had yawned at second base. Dos Joses, tambien. Nobody saw Endy Chavez coming, yet the erstwhile Met-killer (and before that Met farmhand) arrived to fill in all over the outifeld with defensive aplomb and timely hititng. Ancient Julio Franco revived as a pinch-hitter and team leader. Lastings Milledge showed a sample of his first-round stuff. Jose Reyes and David Wright had blossomed into the superstardom that had been projected for them. Paul Lo Duca (Captain Red Ass, per SI) made us more or less forget Mike Piazza was still active and playing for somebody else. Carlos Beltran shook off his first-year New York tentativeness and put up MVP numbers. Carlos Delgado represented more of a good Carlos thing; between them, Belgado stroked 79 homers and drove in 230 runs. ¡Dos Carloses son mejores quen uno! Nobody saw Jose Valentin coming, yet he was hitting home runs regularly and filling the gap that had yawned at second base. Dos Joses, tambien. Nobody saw Endy Chavez coming, yet the erstwhile Met-killer (and before that Met farmhand) arrived to fill in all over the outifeld with defensive aplomb and timely hititng. Ancient Julio Franco revived as a pinch-hitter and team leader. Lastings Milledge showed a sample of his first-round stuff.

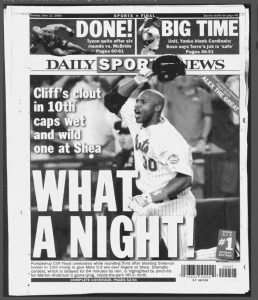

Were there reasons to worry? There are always reasons to worry. Fandom without worry is just wearing t-shirts that have a logo you like. The Cliff Floyd of 2006 wasn’t the Cliff Floyd of 2005, but there were definitely some big hits residing in his bat. He’d be fine. A taxi accident in Miami injured Duaner Sanchez and undermined the strength of our bullpen, motivating Omar Minaya to trade dependable right fielder Xavier Nady for relief depth, but we had a lot of arms out there, plus experienced hitter (and the most accomplished Jewish slugger since Hank Greenberg) Shawn Green on the way to replace ex-Met X-Man. We’d be fine. The starting pitching could be creaky at times, but among Pedro, Gl@v!ne, Trachsel, El Duque and whoever was the fifth starter in whichever week it was, it wasn’t like Willie Randolph couldn’t rely on guile and pedigree, along with blips of promise from younger fellows. We’d be fine. Were there reasons to worry? There are always reasons to worry. Fandom without worry is just wearing t-shirts that have a logo you like. The Cliff Floyd of 2006 wasn’t the Cliff Floyd of 2005, but there were definitely some big hits residing in his bat. He’d be fine. A taxi accident in Miami injured Duaner Sanchez and undermined the strength of our bullpen, motivating Omar Minaya to trade dependable right fielder Xavier Nady for relief depth, but we had a lot of arms out there, plus experienced hitter (and the most accomplished Jewish slugger since Hank Greenberg) Shawn Green on the way to replace ex-Met X-Man. We’d be fine. The starting pitching could be creaky at times, but among Pedro, Gl@v!ne, Trachsel, El Duque and whoever was the fifth starter in whichever week it was, it wasn’t like Willie Randolph couldn’t rely on guile and pedigree, along with blips of promise from younger fellows. We’d be fine.

You get through August with so much fine, you begin to feel invincible. We entered September with the best record in baseball. We were the first team to clinch — actually clinch — a division title. We nailed home-field advantage for the NL playoffs. What could stop us?