The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

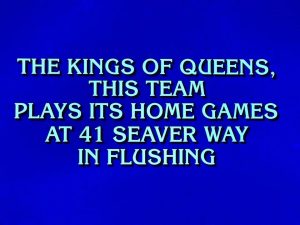

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

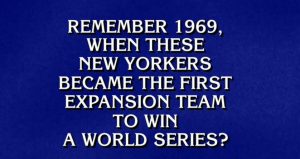

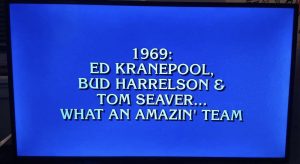

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 13 February 2024 11:09 pm The studio has a few notes on the next installment of MY FAVORITE SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT.

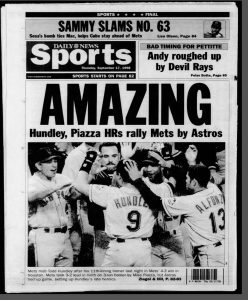

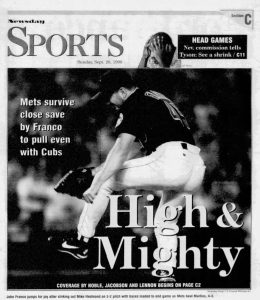

***19. 1998

First off, we love the concept. The Mets as a team you go into the season having expectations for is fresh. I mean, it’s not like it hasn’t been done before, but it will feel fresh to this audience. Our research shows most of our potential ticket-buyers can’t remember the last time they entered a season thinking things would turn out well.

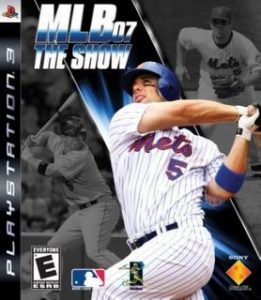

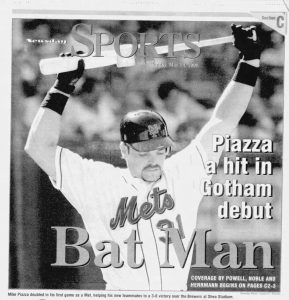

The end of the first act, where you introduce the superstar — unorthodox for timing, but effective. It might have worked better if you could have had him from the beginning of the story, but once you work him in there, he’s a blockbuster unto himself. We’re gonna put him on the posters and everything. The end of the first act, where you introduce the superstar — unorthodox for timing, but effective. It might have worked better if you could have had him from the beginning of the story, but once you work him in there, he’s a blockbuster unto himself. We’re gonna put him on the posters and everything.

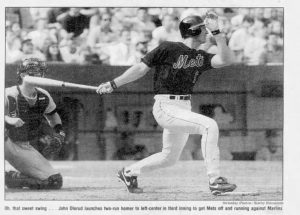

We like some of the supporting cast. The first baseman, for example, is a natural. The hard hat he wears everywhere is supposed to be what, his trademark? Whatever it is, it’s unique. We think it might test well. His hitting you shouldn’t change at all. We like some of the supporting cast. The first baseman, for example, is a natural. The hard hat he wears everywhere is supposed to be what, his trademark? Whatever it is, it’s unique. We think it might test well. His hitting you shouldn’t change at all.

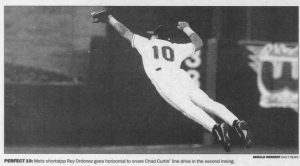

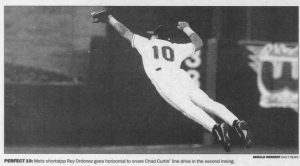

The rest of the infield is…interesting. Listen, we love the scenes where the shortstop fields. Those test off the charts. Well worth the special effects budget that I assume is needed to make him fly through the air. Could he be made into more of a hitter, though? Something to think about. His friend the third baseman plays well in his role, but we hear he has some versatility, and you might want to try him in the part of the second baseman. Nothing wrong with him at third, mind you, but we absolutely have to recast the second baseman. The rest of the infield is…interesting. Listen, we love the scenes where the shortstop fields. Those test off the charts. Well worth the special effects budget that I assume is needed to make him fly through the air. Could he be made into more of a hitter, though? Something to think about. His friend the third baseman plays well in his role, but we hear he has some versatility, and you might want to try him in the part of the second baseman. Nothing wrong with him at third, mind you, but we absolutely have to recast the second baseman.

For starters, and this is the superficial stuff, does the second baseman have to have a mustache? The superstar has a mustache. You really shouldn’t confuse the audience. One mustache grabs your attention. Two is…I don’t know, but it’s too hairy. Unless Charlie Finley is producing your picture, I don’t think the second mustache will fly. Even with special effects. For starters, and this is the superficial stuff, does the second baseman have to have a mustache? The superstar has a mustache. You really shouldn’t confuse the audience. One mustache grabs your attention. Two is…I don’t know, but it’s too hairy. Unless Charlie Finley is producing your picture, I don’t think the second mustache will fly. Even with special effects.

But never mind the face. The body is…I also don’t know, but it’s not that of a dynamic infielder. We need to recast. Or, better yet, take the third baseman — our test audiences really like him — and put him on second, where can form a relationship with the shortstop, and we find somebody else to play the third baseman. That could really make the infield a character unto itself. But never mind the face. The body is…I also don’t know, but it’s not that of a dynamic infielder. We need to recast. Or, better yet, take the third baseman — our test audiences really like him — and put him on second, where can form a relationship with the shortstop, and we find somebody else to play the third baseman. That could really make the infield a character unto itself.

Listen, you’ve got bigger problems in the outfield. You’ve got a motley assortment of players who don’t test well, players who don’t bring in the numbers, and what’s with the former star catcher in left field? We’re gonna have to talk about finding some new outfielders. We have a couple of intriguing names for you to look at later.

The starting pitching…people are not going to pay good money to see this starting pitching. They don’t dislike it, per se, but it’s not a draw. Fix that. Maybe you can get the bullpen in some of these scenes sooner. They’re more interesting. The closer who’s seen it all around here. The still-effective lefty journeyman who’s making his umpteenth stop on the circuit. The flaky one slamming that thing on the mound. We can merchandise that.

I know the closer has a mustache, but that’s OK. He’s a pitcher. The superstar is a catcher. They just can’t wear the same number is all. I know the closer has a mustache, but that’s OK. He’s a pitcher. The superstar is a catcher. They just can’t wear the same number is all.

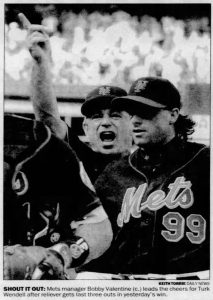

We love the character of the manager. He’s just off-center enough to keep your attention, just good enough at what he does that he seems believable. Is he based on anybody real? The general manager, on the other hand, may be a little too slick. I don’t see the manager and the general manager co-existing in this story. Not that big a deal maybe.

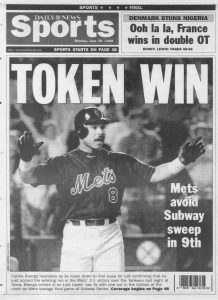

What I’m really concerned about is the story arc. We have the expectations at the beginning, swell. We have the superstar arrive when he does, the crowd eats it up. Again, off the charts with the testing. Even the adversity the superstar faces. He’s gotta have some reason to brood on the poster, am I right? What I’m really concerned about is the story arc. We have the expectations at the beginning, swell. We have the superstar arrive when he does, the crowd eats it up. Again, off the charts with the testing. Even the adversity the superstar faces. He’s gotta have some reason to brood on the poster, am I right?

You have the right idea about making this a story you can’t turn away from for the entire length of the picture. They’re trying to meet the expectations, which elevate in the middle of the arc, with the coming of the superstar, and they’re convincing everybody they just might if they can overcome their flaws, and the superstar and his mustache settle in, and the first baseman with the hard hat goes wild in his mild way, and that third baseman…maybe everybody calls him by a catchy nickname. The shortstop dazzles, even if he can’t hit…great. A couple of those starting pitchers come through. The debonair lefty tests well. The hardscrabble righty, too. I don’t know if you need the second pitcher from Japan, the…what’s he called? “Tornado”? Good nickname, but it could be confusing, like the mustaches. Yes, I know we signed off on him in concept, but we may have to rethink. It would be nice if we could call one of those starting pitcher characters “Ace,” but it might be taken as ironic. The flake reliever slamming the thing fits in any situation — we love that he’s used so often. Even that washed-up catcher who’s been exiled to the outfield who has one moment late in the picture moves the dials. You’ve got a lot of compelling scenes. Gripping, even.

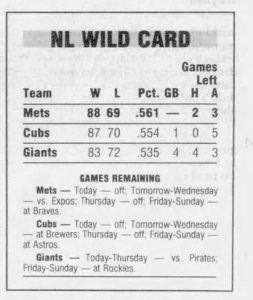

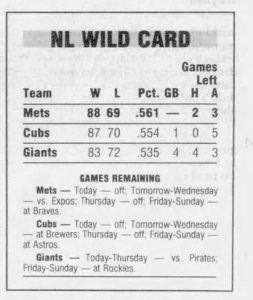

But does the end have to be so goddamn depressing? The whole bunch engages you all summer and keeps you hanging on into September and then in the last week we’re supposed to deal with them doing nothing but losing? Then going home? It’s just so…heavy. People are going to walk in, expecting something light and uplifting and then you want them to leave in a mood? Maybe it’s more artistic your way, but it’s not commercial. For us to greenlight this project, we’re gonna have to meet in the middle. But does the end have to be so goddamn depressing? The whole bunch engages you all summer and keeps you hanging on into September and then in the last week we’re supposed to deal with them doing nothing but losing? Then going home? It’s just so…heavy. People are going to walk in, expecting something light and uplifting and then you want them to leave in a mood? Maybe it’s more artistic your way, but it’s not commercial. For us to greenlight this project, we’re gonna have to meet in the middle.

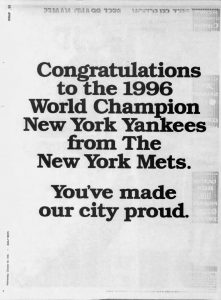

Also, do we have to have two bands of villains shooting down the hopes and dreams? We’d rather there be either the haughty rival from down south that almost never finds a way to lose OR the even haughtier rival from the same city that literally never finds a way to lose. It’s too much to ask to have take on both of them. Very frustrating from an audience perspective. I know we have equity in miracles and all that, but c’mon. Also, do we have to have two bands of villains shooting down the hopes and dreams? We’d rather there be either the haughty rival from down south that almost never finds a way to lose OR the even haughtier rival from the same city that literally never finds a way to lose. It’s too much to ask to have take on both of them. Very frustrating from an audience perspective. I know we have equity in miracles and all that, but c’mon.

Oh, and the wardrobe choice — black? Really? Stop trying to think like a marketer. Leave that to the professionals.

If you’re absorbing anything I’ve said today, you’ve got to work on the ending. And recasting those roles I mentioned. It’s not beyond hope, though. Far from it. If anything, you’re too close to not get this right. Make those changes we discussed, come back next year, and I bet we’ll have a massive hit on our hands.

PREVIOUS ‘MY FAVORITE SEASONS’ INSTALLMENTS

Nos. 55-44: Lousy Seasons, Redeeming Features

Nos. 43-34: Lookin’ for the Lights (That Silver Lining)

Nos. 33-23: In the Middling Years

Nos. 22-21: Affection in Anonymity

No. 20: No Shirt, Sherlock

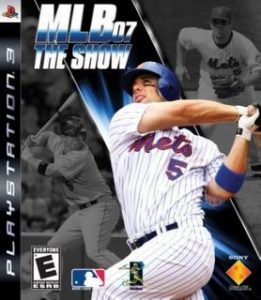

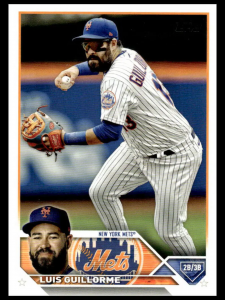

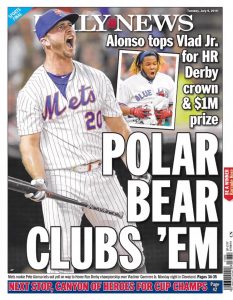

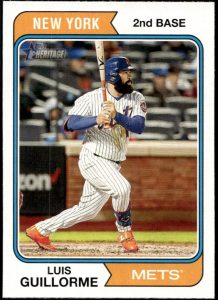

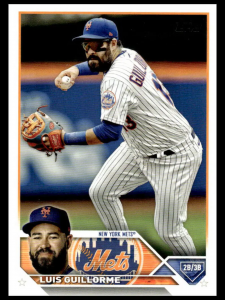

by Greg Prince on 12 February 2024 2:50 pm Just in time for Pitchers & Catchers, we have broken into the Top 20 portion of MY FAVORITE SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT. The focus of this entry is neither a pitcher nor a catcher, but he does happen to be somebody who will be reporting to Port St. Lucie in the company of this year’s batterymates in the days ahead. In a happy accident of my not having picked up the pace on this project, this look back through one fan’s lifetime of rooting for teams he didn’t love that much; loved somewhat; loved a whole lot; and, ultimately, loved more than any other is actually kind of timely.

You’ll recognize the modern-day Met in question in about a minute if you haven’t already. Here’s hoping that player’s current contractual situation is resolved to our liking before we are tempted to apply regret to our long-term reading of how we arrived at his professional crossroads. We know we have him at the outset of 2024. We yearn to hear we’ll have him in 2025 and beyond. But no matter what the near future holds, we will always know what we had when we first wrapped our arms around who he was and what he could do for us. I’m certain I will always be glad the wrapping began when it did.

***

20. 2019

In the runup to the 2019 season, new camera-ready general manager Brodie Van Wagenen communicated a lot of things to the media, including, around mid-January, this assessment of the offseason he’d conducted to date:

“We are a good team. We are a complete team, we are a balanced team. We’ve got veterans, we’ve got youth, we’ve got a hunger and desire to win and I look forward to showing people we’re a team to be reckoned with. Let’s not be shy about wanting to be the best, and I fully expect us to be competitive and be a winning team. Our goal is to win a championship and it starts with the division, so come get us.”

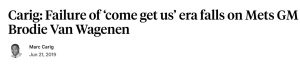

The last three words, uttered on the occasion of the Mets signing the cherry on top of Van Wagenen’s winter, former Oakland middle infielder Jed Lowrie, had Freezing Cold Take penciled all over it once the Mets dipped below .500 in early May. “Come get us” might as well have been the team’s and the GM’s epitaph by the All-Star break, a juncture that found the Mets ten games under and holding the second-worst record in the entire league. With any luck, the Mets figured to improve from what they’d been in 2018 (77-85), but were neither the consensus pick nor a “smart money” selection to upend the National League East. “We’re coming for you” would have been a more appropriate tone to strike a year after languishing in fourth place. Hubris was a hairdo that didn’t accent these Mets’ better features.

If you shared your thoughts about the Mets with any kind of audience in 2019 and you wanted to score a chagrined grin at the expense of a very handsome man, you reminded everybody reading or listening of the dare Van Wagenen left on the doorsteps of the Braves and the Nationals and how the competition was in the process of responding (the Braves were en route to winning the East and the Nationals would cash in the Wild Card for their first world championship). BVW, as he was destined to be shorthanded in these social media times, knew when foot fit mouth. Ahead of the second half, he admitted to reporters, “They came and got us.”

But Brodie Van Wagenen, as mentioned, said a lot of things ahead of the first Met campaign played on his watch, including three less celebrated sentences just prior to the opening of the 2019 season. Within his tumultuous tenure’s mixed bag of quotations and transactions, perhaps a little more attention needed to be paid to this sentiment:

“I’m not of the mindset that we should be sacrificing the best product for the fans or the best product for the other 24 guys in the clubhouse to save service time or potential future money six years down the road. If Pete Alonso or anybody on our roster is good enough to have six consecutive years without having a hiccup, or without ever having to go to the minor leagues, that’s a good, high-class problem for the player. It’s a high-class problem for the organization.”

Sometimes class tells. Sometimes a GM continually and not unfairly strafed for setting an unrealistic bar knew what he was doing. Sometimes a mixed bag implies there are some tasty morsels included among the dregs.

Rookie first baseman and potentially prodigious slugger Pete Alonso made the Opening Day roster of the 2019 Mets. it was no sure thing. True, their 2018 predecessors were no great shakes; there was no incumbent with a hammerlock on Pete’s position; and the kid had dominated Triple-A pitching. Only in Major League Baseball would that confluence of circumstances not mean a job definitely awaited a young comer. But Pete played baseball. Baseball liked to tell kids who were ready to go in March that they should stick around the minors for a few weeks and cool their heels, lest they accumulate the service time that would make them free agents a year sooner six years from now.

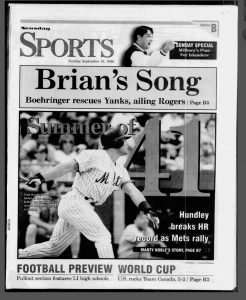

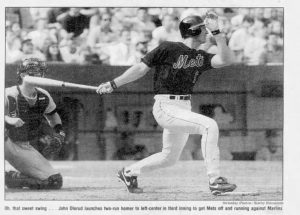

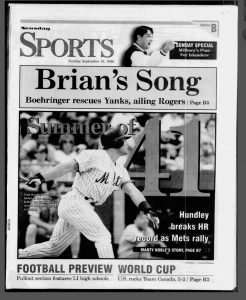

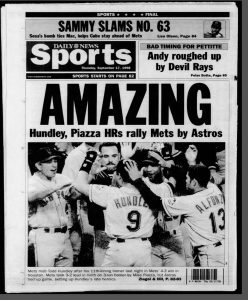

Yet Pete made the Mets out of Spring Training 2019, circumstances for the offseason that would precede 2025 be damned. Brodie will always rate a gold star for not making Pete or Mets fans wait one minute more. Pete took advantage of his organic start to his first season and blew away whatever hype we’d heard. His first game was Opening Day. His first home run came in the Mets’ fourth game. Twelve games into his major league career, he had six home runs. He ended April with nine. By May, the month I had the privilege of finally witnessing in person one of his Citi Field bombs (No. 16, confirmed fair by replay review), I took it upon myself to start tracking his power progress versus the co-holders of the Met single-season home run recordholders, Todd Hundley (1996) and Carlos Beltran (2006), as well as the fella who, until he was halted by injury, was going to put the record out of reach for a generation, the legendary Dave Kingman in 1976. Yet Pete made the Mets out of Spring Training 2019, circumstances for the offseason that would precede 2025 be damned. Brodie will always rate a gold star for not making Pete or Mets fans wait one minute more. Pete took advantage of his organic start to his first season and blew away whatever hype we’d heard. His first game was Opening Day. His first home run came in the Mets’ fourth game. Twelve games into his major league career, he had six home runs. He ended April with nine. By May, the month I had the privilege of finally witnessing in person one of his Citi Field bombs (No. 16, confirmed fair by replay review), I took it upon myself to start tracking his power progress versus the co-holders of the Met single-season home run recordholders, Todd Hundley (1996) and Carlos Beltran (2006), as well as the fella who, until he was halted by injury, was going to put the record out of reach for a generation, the legendary Dave Kingman in 1976.

I couldn’t go deep on the subject of Met moonshots without thinking about Sky King. Unless a few stray Bicentennial fireworks knocked a couple of his longballs off course, a Mets fan in the summer of ’76 had every reason to believe Kingman was going to place Hack Wilson’s National League standard of 56 home runs in danger. Dave swatted his 32nd home run in the Mets’ 92nd game, a pace four games better than Pete’s 43 years later. Alas, in their 93rd, he messed up a thumb attempting to play defense and would miss too much time to take his hack at Hack. Dave wound down 1976 with 37 home runs, which did establish a new Met record (breaking his own from 1975), but not one you required a telescope to detect. In a way, Pete’s only legitimate competition was eliminated more than three decades before the rookie took his first swing.

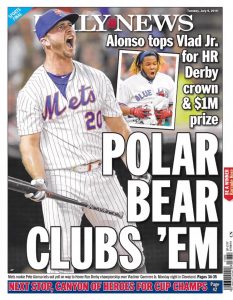

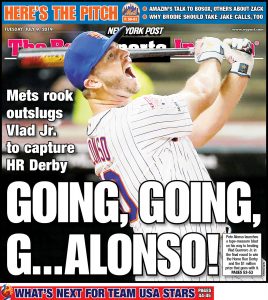

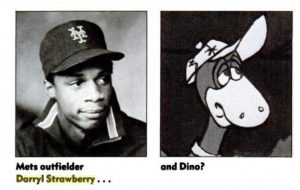

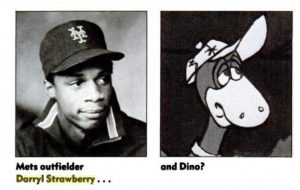

Hundley and Beltran, who finished their big years with 41 home runs apiece, proved modest hurdles for Alonso. Within Pete’s first 50 games, the Polar Bear — an apt and adorable nickname contemporary accounts suggest was crowdsourced by some combination of Todd Frazier, Noah Syndergaard and coach Gary DiSarcina — had gone over fences 17 times. By comparison, Todd required 64 games to hit that many home runs and Carlos needed 60. By the time Pete experienced a brush with a home run drought (no homers between Met Game 103 and Met Game 113), Pete’s cushion separating him from his predecessors was a veritable sofa bolster. The rookie who’d hit the most Met home runs previously, Darryl Strawberry in 1983, likewise couldn’t retroactively keep up. Strawberry, whose 39 homers in 1987 would surpass Kingman’s Met best from eleven years earlier, was promoted to the bigs on May 6 of his first year and put those nearly five months of NL action to very good use, clouting 26 homers and earning Rookie of the Year honors. His 1983 total seemed like such a formidable freshman number for so long, but Pete left Darryl’s initial quantity in the dust before the first half of 2019 was over. In only three months, that line of the Met record book was rewritten. Hundley and Beltran, who finished their big years with 41 home runs apiece, proved modest hurdles for Alonso. Within Pete’s first 50 games, the Polar Bear — an apt and adorable nickname contemporary accounts suggest was crowdsourced by some combination of Todd Frazier, Noah Syndergaard and coach Gary DiSarcina — had gone over fences 17 times. By comparison, Todd required 64 games to hit that many home runs and Carlos needed 60. By the time Pete experienced a brush with a home run drought (no homers between Met Game 103 and Met Game 113), Pete’s cushion separating him from his predecessors was a veritable sofa bolster. The rookie who’d hit the most Met home runs previously, Darryl Strawberry in 1983, likewise couldn’t retroactively keep up. Strawberry, whose 39 homers in 1987 would surpass Kingman’s Met best from eleven years earlier, was promoted to the bigs on May 6 of his first year and put those nearly five months of NL action to very good use, clouting 26 homers and earning Rookie of the Year honors. His 1983 total seemed like such a formidable freshman number for so long, but Pete left Darryl’s initial quantity in the dust before the first half of 2019 was over. In only three months, that line of the Met record book was rewritten.

Pete was running roughshod over modern-day pitching, and franchise history couldn’t keep up with him, either. As 2019 went on, it was clear Pete Alonso was doing things in terms of home runs no Met had done before. It was just as clear to me that I was never as thrilled by any individual Met’s pursuit of any type of benchmark, record or title as I was by Pete’s. The thrill transcended mere statistics because, despite the skies over Shea and Citi having been effectively pierced by the likes of Kingman, Strawberry, Hundley and Beltran, this simply wasn’t an outfit defined by balls it put over walls.

When it came to four-baggers, we’d always ordered our most dramatic and memorable à la carte.

• Willie Mays coming home to the city that never didn’t consider him its own, May 14, 1972.

• Steve Henderson making Magic real, June 14, 1980.

• Gary Carter trying on orange and blue and demonstrating how well it fit, April 9, 1985.

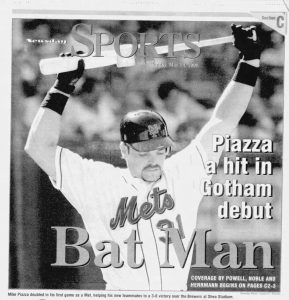

• Mike Piazza when nobody knew what to expect other than Mike Piazza doing something dramatic and memorable, September 21, 2001.

• Wilmer Flores absolutely not getting traded, July 31, 2015.

Donn Clendenon in the World Series. Al Weis in the World Series. Lenny Dykstra and Benny Agbayani to end playoff games. Todd Pratt to end a playoff round. Lee Mazzilli late one All-Star night. Throw in Tommie Agee and Curtis Granderson from the leadoff spot; Yoenis Cespedes and his enormous spurt; Howard Johnson going on rolls; Lucas Duda, too. Circle back to Piazza, the Ginger Rogers of power hitters. He hit them far, he hit them often, and he hit them while half the time doing the baseball equivalent of backwards and in high heels. Mike crouched, called games and looked out at the field as only the catcher does.

Yet even Mike Piazza with his flair for the dramatic and memorable didn’t make home runs the main course of the Met menu. It was like we were on a restricted diet. When we were good, we were about pitching, glovework and fairy dust. What should be our most famous not to mention dramatic and memorable postseason home run went into the books as a grand slam single. Pratt tackled Robin Ventura before Robin Ventura could touch second let alone home. No thanks, Tank seemed to tell his teammate amid the delirium of October 17, 1999, we can’t eat another bite. It’s still dramatic and memorable, but it’s missing more than 180 feet worth of calories.

Another third baseman, David Wright, should have been, per the terms of his contract and the arc of the healthy segment of his career, extending his all-time franchise home run record in 2019. Except he stepped aside for good in 2018, having been sidelined for all but a couple of games that year and completely out of action the year before that and most of the two years before that. Wright, a steady rather than spectacular slugger, completed his Met clouting at 242 home runs, ten shy of Strawberry’s 252. Strawberry’s 252 were like Hundley’s and Beltran’s 41. Really, really good when you stopped and thought about it, but once you realized what home run figures other franchises had inked into their annals, not exactly super.

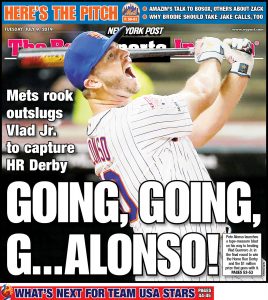

Then along comes the Polar Bear, almost unstoppable in the home run category practically from Day One, definitely in Year One, giving us permission to gorge. Somehow something that Pete made mundane qualified as an event. Another Apple-raiser for Alonso! In another era, crowds would have gathered in Times Square to learn of his exploits from the news racing around the zipper, the town, the nation, the world to keep up with the newly crowned Home Run Derby champ. His 30th! His 40th! His 41st to tie the Met record! His 42nd to break it! His blitz through the forties and, ohmigod, his 50th! A Met hit 50 home runs! Then a 51st! A 52nd, tying the all-time rookie record with two games left! And, in the season’s penultimate game, Pete Alonso of the New York Mets hit his 53rd home run, more than any rookie ever, more than anybody in Major League Baseball in 2019. He was already fewer than 200 from Strawberry’s Met career mark and he’d played precisely one season. Then along comes the Polar Bear, almost unstoppable in the home run category practically from Day One, definitely in Year One, giving us permission to gorge. Somehow something that Pete made mundane qualified as an event. Another Apple-raiser for Alonso! In another era, crowds would have gathered in Times Square to learn of his exploits from the news racing around the zipper, the town, the nation, the world to keep up with the newly crowned Home Run Derby champ. His 30th! His 40th! His 41st to tie the Met record! His 42nd to break it! His blitz through the forties and, ohmigod, his 50th! A Met hit 50 home runs! Then a 51st! A 52nd, tying the all-time rookie record with two games left! And, in the season’s penultimate game, Pete Alonso of the New York Mets hit his 53rd home run, more than any rookie ever, more than anybody in Major League Baseball in 2019. He was already fewer than 200 from Strawberry’s Met career mark and he’d played precisely one season.

WOW!!!!

Yet one player does not make a season. I base this assertion on having lived through Pete’s very exciting power show when it served as counterpoint to the way the Mets were going as a whole, and I gotta say, what the Mets besides Alonso (along with that Jacob deGrom fellow on his way to another Cy Young) were giving us wasn’t much of a 2019.

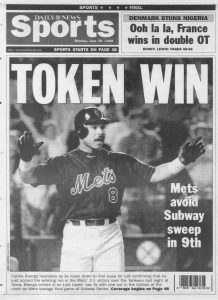

Until it was. That took everybody’s contribution. Suddenly, in late July, right around the moment Pete matched Frank Thomas’s original single-season Met home run record of 34, the hat was being passed incredibly effectively. From Jeff McNeil to Michael Conforto to J.D. Davis to Amed Rosario to Wilson Ramos until it reached Dom Smith in the eleventh inning of the season’s final game. Every Met was kicking in a little, then a lot. The team Van Wagenen constructed was living up to the GM’s chest-puffing at last.

Pete hitting a ton of home runs while the Mets stumbled to a 40-51 start: plenty fun when he batted, not much fun otherwise.

Pete hitting a ton of home runs while the Mets racked up a 46-25 finish: baseball like it oughta be.

The 86-76 Mets didn’t assume the guise of a contender until it was a tad too late to dent the playoff race in earnest. Ah, but we didn’t fully know that until we claimed hindsight on irrevocable waivers. We sensed it repeatedly in late August and early September and mid-September, the way you do when you know deep down you’re bound to fall a little short, yet every time we were ready to throw in the towel, the linen would not leave our hand. Our Mets had gotten good enough all at once to let us believe, and that’s always dangerous when we’re determined to be realists. When it was finally too late to any longer deny the inevitable, after a one-run loss in Cincinnati during the season’s second-to-last weekend stuck the club 4½ out of the final playoff spot with eight to play, Todd Frazier tried like hell to work the long mathematical odds in the Mets’ favor. “I felt like we had to go 9-1” down the stretch, the Toddfather reasoned. “Here’s our one.” I knew desperation was talking and didn’t invest much hope in Frazier’s calculation. They were indeed ousted from the race a few days hence.

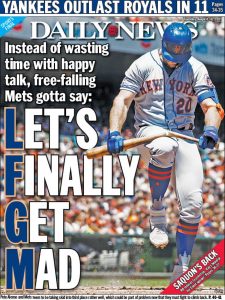

Still, Todd from Toms River wasn’t necessarily talking crazy. He was part of a team that between July 25 and August 10 went 15-1 and completely changed the tenor of their season. From a unit that was mainly about Pete Alonso hitting home runs, they evolved into a unit that was all about winning games, contending for a Wild Card and having a blast while trying to pick up ground. The veterans, the youth, the hunger and desire to win that Brodie Van Wagenen promised in January were all in evidence. It was during the 15-1 stretch that they started pulling off the jersey of the given evening’s hero to celebrate walkoff wins; that players not named Pete Alonso began getting our attention for Amazin’ feats; that LFGM became an accepted spelling for Let’s Go Mets; and that anything began to seem possible. It didn’t propel the 2019 Mets to come get a playoff spot when it seemed like they had a real chance, but it was enough to transform a season that had been a veritable one-man show into the kind of team effort that keeps a fan tuning in out of anticipation rather than habit. Still, Todd from Toms River wasn’t necessarily talking crazy. He was part of a team that between July 25 and August 10 went 15-1 and completely changed the tenor of their season. From a unit that was mainly about Pete Alonso hitting home runs, they evolved into a unit that was all about winning games, contending for a Wild Card and having a blast while trying to pick up ground. The veterans, the youth, the hunger and desire to win that Brodie Van Wagenen promised in January were all in evidence. It was during the 15-1 stretch that they started pulling off the jersey of the given evening’s hero to celebrate walkoff wins; that players not named Pete Alonso began getting our attention for Amazin’ feats; that LFGM became an accepted spelling for Let’s Go Mets; and that anything began to seem possible. It didn’t propel the 2019 Mets to come get a playoff spot when it seemed like they had a real chance, but it was enough to transform a season that had been a veritable one-man show into the kind of team effort that keeps a fan tuning in out of anticipation rather than habit.

Moral: tracking a ballclub’s collective success beats tracking that of one individual, no matter how powerful the Polar Bear in the spotlight.

PREVIOUS ‘MY FAVORITE SEASONS’ INSTALLMENTS

Nos. 55-44: Lousy Seasons, Redeeming Features

Nos. 43-34: Lookin’ for the Lights (That Silver Lining)

Nos. 33-23: In the Middling Years

Nos. 22-21: Affection in Anonymity

by Greg Prince on 4 February 2024 1:48 pm En route from the bottom 60% of MY FAVORITE SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT — Nos. 55–44 here; Nos. 43–34 here; Nos. 33–23 here — to the just plain Top 20 (expressed without a percentage sign because they are, in fact, Nos. 20–1), I need to make a stop in consecutive years to explore No. 22 and No. 21 on my list. It’s a convenient coupling and can’t possibly be coincidental, but I’m pretty sure the adjacent nature of these seasons in my ranking of favorites is just that.

The two seasons we are about to visit do exist adjacently in both my affections and their chronology. They are bound together by one ginormous event that was a huge factor in our baseball lives for 232 days. It (along with winter, one supposes) was the reason there was no baseball in that span. Then the ginormous event was over and receded into the backstory of our game, though not as far back as the two Met seasons it linked. These seasons are utterly anonymous in any garden-variety retelling of Met history, which may be just as well since they happened almost off the narrative grid that’s taken us from 1962 to the present. In their limited time as the present, both years were about new beginnings. The first of them didn’t take in such a capacity — that aforementioned ginormous event cut if off before it could gain traction; at least it stanched the bleeding of the season that preceded it. The second of them hinted at what was ahead, but doesn’t quite fit the role of harbinger of an era to come. A little here and there, perhaps, but it, too, doesn’t connect neatly to its relatively near future.

Yet here they are, on the edge of the Top 20, ranked above 33 of the Met seasons through which I have lived and rooted. I have maintained above-average affection for these two years despite their anonymity, or maybe as an ode to it. I know I lived them. I know I rooted during them. I remember ripples of gratification obscuring these seasons’ obvious imperfections. I liked these years a good deal then. To say I treasure them now might be an exaggeration, but I’m guessing they’ve stayed closer to my Met heart than they’ve hung around the Met heart of others. That’s just where I’ve kept them since I first found them roughly three decades ago, and it’s never occurred to me to shove them all the way into the back of my memory’s storage unit.

Keep the seasons nobody else thinks about handy. You never know when you’ll need them.

***22. 1994

No World Series in 1994? The hell you say! I experienced my version of the Fall Classic throughout the spring and as much summer as the feuding factions of MLB would allow. My World Series pitted the Mets versus how bad the Mets could have been. Respectability captured the only Series that mattered in 113 games. Context was named MVP.

True, there was no actual World Series that year. I prefer to err on the side of “big whoop” where that widely bemoaned cancellation is concerned. When Commissioner Bud Selig announced more than a month after the Players Association struck Major League Baseball that the World Series was canceled, garments were rent and wails went up. Millionaires and billionaires arguing!!! How could they do this to the WORLD SERIES?!?! I’ll never watch another game!!! I was approximately 5% sympathetic, 95% STFU with that BS, except I probably didn’t use acronyms. True, there was no actual World Series that year. I prefer to err on the side of “big whoop” where that widely bemoaned cancellation is concerned. When Commissioner Bud Selig announced more than a month after the Players Association struck Major League Baseball that the World Series was canceled, garments were rent and wails went up. Millionaires and billionaires arguing!!! How could they do this to the WORLD SERIES?!?! I’ll never watch another game!!! I was approximately 5% sympathetic, 95% STFU with that BS, except I probably didn’t use acronyms.

Yes, the World Series oughta be sacrosanct, but no more so than the regular season that sets its stage, which in 1994 had a curtain pulled down over it on August 11 after negotiations regarding a salary cap the owners wished to impose went nowhere. If you couldn’t get back to your schedule and play it to some sort of conclusion, why would a World Series matter? I start to care about the World Series in an earnest, nonpartisan way once the identity of the pennant-winners comes into focus. We were miles from those big reveals on August 11.

None of this had a darn thing to do with the Mets in 1994, which may also be why the World Series talk rang hollow with this diehard baseball fan. On the last night games were played, the Mets sat 12½ games from a postseason berth, the first time one was compelled to apply such nomenclature to baseball. Before 1994, we’d simply state how many games out of first place a team that wasn’t in first place was, and you had all you needed to know. But now, like every other sport, baseball offered side doors to the playoffs. The Wild Card was brand new in ’94, one per league. The Mets weren’t in the running for one of those. Nor, at 18½ games from the top of the NL East, was first place realistically attainable to them in their realigned division. The Expos were on fire and the defending Western Division champion Braves never lost a step when somebody finally decided to get geographically correct about their Georgia location. Let Expos fans and Braves fans and other teams’ fans regret the lack of a 1994 World Series. It wasn’t our problem. I was the prototype for football coach Jim Mora bellowing at the assembled Indianapolis media, “PLAYOFFS?” when a reporter dared ask him if his 4-6 Colts still had a shot at playing for the Super Bowl.

Yet I didn’t get mad that the Mets had no chance at any canceled playoffs, because the 1994 Mets were getting close to getting even in the winning percentage column. They succeeded wildly at not sucking all that much. T-shirts weren’t licensed and sold at Modell’s to celebrate the accomplishment, but I guarantee you if they had been, I’d have bought one. Not automatically expecting to lose can move theoretical merchandise.

The Mets’ record of 55-58 is a little misleading in communicating a sense of their ability to sustain stretches of competent baseball. They were surprisingly good in the first and final swaths of their limited season (18-14, 22-15), a stone drag in the ad hoc middle (15-29). Their composite mark left them four wins shy of their 59-victory sum from 1993, which, it should be noted, was compiled across a slate of 162 mostly miserable games. There’s that most valuable context coming to the fore: it was no longer 1993 for the Mets. That year’s team was a grim laughingstock. If it’s darkest before the dawn, 1994 represented those five or ten minutes ahead of the time listed for sunrise. It was no longer pitch black outside. You could begin to see clearly now.

Had there been no strike and the Mets maintained their .487 winning percentage — sixth-best in the entire National League — that would have been good for 79 wins, a gain of twenty from 1993, not to mention a couple of lucky bounces from being a winning team one year removed from being the butt of David Letterman’s monologue. Had they reverted to the low expectations 1993 wrought, they were still highly unlikely to lose as many as 90 games. The Daily News ran a computerized simulation of the daily standings during the strike in lieu of the real thing. According to Bill Konigsberg and Pursue the Pennant, the 1994 Mets “would” have gone 73-89. Not great, but a legit hop, skip and/or jump from the 59-103 that weighed us down in ’93.

I keep coming back to 1993 even as I praise 1994 for getting us away from it. Perhaps I was prone more than I realized to a condition we’ll label Marlin Envy. Yeech, I know, but Florida was a fresh new team in 1993. Colorado, too. I’d never experienced National League expansion from the ground up. Ballparks you hadn’t seen before. Logos you hadn’t seen before. Names from out of nowhere that lodged themselves onto the schedule and into your consciousness. Teal! Purple! The novelty was bracing. What was less delightful was being the one established unit in the senior circuit incapable of taking advantage of the neophytes. We finished behind the Marlins in 1993. We finished behind the Rockies in 1993. We finished behind everybody in 1993.

If you can’t beat ’em, sort of replicate ’em. The 1994 Mets came off a bit like a modern expansion outfit themselves. Not in line with the 1962 version of themselves, but the way expansion teams were constructed in the ’90s, with a handful of high-priced players mixed in with the prevailing gumbo of discards and kids getting a chance they might not have arisen had these extra jobs not been open. The team charter flew by the seat of its pants. Opening Day was April 4. Our Opening Day first baseman, David Segui, was acquired on March 27. Our Opening Day shortstop, Jose Vizcaino, joined the organization on March 30. The first week of the season included the Met debuts of seven other players guaranteed to set few fans’ hearts aflutter. Unheralded rookies Fernando Viña and Kelly Stinnett. Downswing retreads Pete Smith and John Cangelosi. Scrap heapsters Jonathan Hurst, Doug Linton and Luis Rivera. Yet with these and the rest of the Mets off and running to a start of 4-1, who gave a damn about their non-reputation? If we knew the term “replacement level,” we would have embraced it. All we wanted was to replace the bitter taste of 1993.

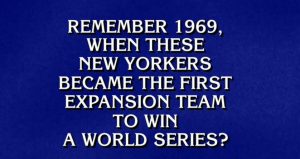

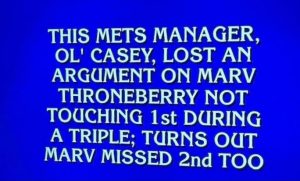

Of the 37 players who wore the Miracle Mets 25th anniversary sleeve patch in 1994 (you don’t have to be a uniform sleuth to pick out ’94 highlights), only four — Dwight Gooden, Kevin McReynolds, John Franco and Todd Hundley — had previously played for a Mets team that had posted a winning record, something no Mets team had done since 1990. If we were moving on from 1993, we were also inextricably separated from the suddenly not so recent golden age of Mets baseball. Gooden was the last 1986er extant on the roster. 1988’s near-MVP McReynolds returned after a two-year absence, Kansas City offloading him on us so we could dump Vince Coleman on them. K-Mac wouldn’t be back after 1994. Doc, testing positive like it was 1987, wouldn’t last until the strike. When the 1969 Mets were introduced at a distressingly empty Shea Stadium on July 24 (nothing personal, fellas — Mets attendance landed near the bottom of the NL), they were the only world champions in sight. Of the 37 players who wore the Miracle Mets 25th anniversary sleeve patch in 1994 (you don’t have to be a uniform sleuth to pick out ’94 highlights), only four — Dwight Gooden, Kevin McReynolds, John Franco and Todd Hundley — had previously played for a Mets team that had posted a winning record, something no Mets team had done since 1990. If we were moving on from 1993, we were also inextricably separated from the suddenly not so recent golden age of Mets baseball. Gooden was the last 1986er extant on the roster. 1988’s near-MVP McReynolds returned after a two-year absence, Kansas City offloading him on us so we could dump Vince Coleman on them. K-Mac wouldn’t be back after 1994. Doc, testing positive like it was 1987, wouldn’t last until the strike. When the 1969 Mets were introduced at a distressingly empty Shea Stadium on July 24 (nothing personal, fellas — Mets attendance landed near the bottom of the NL), they were the only world champions in sight.

Maybe the most compelling evidence that time was marching on came from the box score of April 5, the season’s second game. Dallas Green, in what was supposed to be his first full season of getting the Mets back on their feet, used a dozen players to beat the Cubs that afternoon. None of the twelve was alive on April 11, 1962, the official date of birth for Casey Stengel’s baby Mets. Our actual expansion roots, just like our glory days, were also growing more and more distant.

In a way, the 1994 Mets, commemorative patch notwithstanding, were, for better or worse, unmoored from their past. It was probably a necessary detachment. The Mets’ past was no longer providing a useful template for their immediate future. Their nascent present was about to evaporate on August 11, anyway. Nineteen players who were Mets in 1994 wouldn’t be Mets in 1995. Some of that was the attrition of a long strike, some of it a fact of replacement level life. For those of us just learning to communicate via computer, the phrase “reboot” was entering our lexicon. Perhaps that’s what we were experiencing as Mets fans back then. Our screen froze in 1993. Somebody must have told us to unplug, then plug back in and see if it works.

Son of a gun, it did. But maybe someone from IT needed to come by and take a closer look to figure out what exactly was going on.

21. 1995

Had the power rankings contrivance existed in 1995, the Mets might have crept to the fringe of the middle of the pack by the end of the season, decently above the cellar-dwelling rabble, far beneath your momentum-laden outfits like the Refuse to Lose Mariners and your eventual World Series combatants Atlanta and Cleveland. But that was no way to measure what we who were paying attention to our Amazins had goin’ on. Comparing the Mets to the powerhouses of the day wouldn’t have reflected the velocity with which our mood had risen. Had we worn mood rings, you would have seen ours turning violet, the color indicating the ring in question wraps around the finger of a person feeling very happy.

Mood rings weren’t undergoing a renaissance in the early fall of 1995, but the Mets sure were, a stark reversal from where they started in baseball’s late spring. The all-encompassing strike that knocked out everything the previous August through October crossed the line from one year to the next as 1994 became 1995. We didn’t know when our game would be played again, and we didn’t know who would play it. The owners, unable to pierce the resolve of the Players Association, hatched a scheme to hire replacement players. Not replacement level players (the Mets had already tried that in ’94), but minor leaguers not subject to union rules; stray retirees who thought they had something left; and, essentially, some dudes off the street. If you put them in major league uniforms and told the fans that these fellas were now your favorite players, maybe it fool some of the people some of the time. Mood rings weren’t undergoing a renaissance in the early fall of 1995, but the Mets sure were, a stark reversal from where they started in baseball’s late spring. The all-encompassing strike that knocked out everything the previous August through October crossed the line from one year to the next as 1994 became 1995. We didn’t know when our game would be played again, and we didn’t know who would play it. The owners, unable to pierce the resolve of the Players Association, hatched a scheme to hire replacement players. Not replacement level players (the Mets had already tried that in ’94), but minor leaguers not subject to union rules; stray retirees who thought they had something left; and, essentially, some dudes off the street. If you put them in major league uniforms and told the fans that these fellas were now your favorite players, maybe it fool some of the people some of the time.

Thanks to a U.S. District Court judge named Sonia Sotomayor, we never discovered just how gullible we might be. Sotomayor issued an injunction against the owners on the eve of Fauxpening Day, keeping them from unilaterally subverting the collective bargaining tenets that had been in place before the strike. In short, play ball!

Alas, the Mets weren’t prepared to do so, or at least not do it well. On April 26, after an abbreviated Spring Training, they lost their first game, the first game ever played at Coors Field in Denver. On April 27, they lost the second game ever played at Coors Field in Denver. For the first time since 1965, the Mets were 0-2. Two home wins followed (disgruntled fans tossed money at the players in the Shea Opener), boosting the 1995 Mets to .500 for the first and last time.

The season would be shortened to 144 games in deference to the late start. Yet the season started getting long real soon. That’ll happen when your team drifts from .500. For a spell, it wasn’t bothersome. Just having baseball back was a thrill, as it is every April. That never lasts, though. Any baseball might beat no baseball, but bad baseball drops out of contention quickly enough.

For the fifth consecutive season, the Mets were wearing home jerseys that didn’t look quite like the jerseys they wore the year before, their search for an identity taking a sartorial twist. In 1991, they’d added buttons to their racing stripe tops. In 1992, there was an “S” patch to honor the late Bill Shea. The 1993 strategy deleted those ’80s side stripes and birthed the wordmark tail nobody asked for; it was still there in 1994, as were, for just that year, MLB’s 125th Anniversary logo on one sleeve and a quarter-century commemorative emblem for the 1969 Mets on the other. In 1995, the Mets’ motif was back to basics…maybe a little too basic. The tail was off the “Mets,” which was a good deletion, and the overall look echoed what you might call the classic motif of 1965 to 1977. Mets in script, number on the front, no muss, no fuss, not bad.

Except there was something about that script “Mets” that struck this viewer as a little too thin, definitely not as hearty as it used to be. It seemed to speak for what the 1995 Mets — who we weren’t even sure were going to be the 1995 Mets when replacement players roamed St. Lucie — thought of themselves.

We don’t want to bother anybody.

We don’t want to get in the way.

Maybe you’ll come out and join us at the ballpark.

Maybe you won’t.

You might not know who all of us are yet, but that’s OK.

Just look for the familiar name on the front.

Whatever you want to do is fine with us.

We still have a hundred-something games left.

We’ll be here even if you’re not.

A fan will see what a fan sees. For quite a while in 1995, I saw an invisible team. When the Mets did appear in a highlight, it was as backdrop for some other team’s development. The Rockies’ new ballpark. Cliff Floyd of the Expos badly banging up his wrist in a first base collision with Todd Hundley. Chipper Jones of the Braves belting his first career home run into the sparsely populated right field Loge seats at Shea. There was minimal carryover from whatever infused with 1994 with hope before the strike. My main Met coming into the season, Rico Brogna, had won me over as a rookie the summer before when he emerged from what seemed like nowhere to bat .351 in 39 games. I waited out the labor-management machinations without rancor because I knew Rico Brogna was waiting on the other side. In the chill of Denver on Opening Night, Rico batted third and blasted the first home run in Coors Field history in the fourth. The Mets lost in fourteen. Rico’s start sizzled like it had in ’94, then cooled off to solid if not spectacular, which describes the injury-abbreviated career that awaited him. I sort of believed he’d keep hitting .351, just as I definitely believed the Mets who finished just shy of .500 in 1994 would storm past the respectability barrier after Judge Sotomayor gaveled some common sense into the National Pastime.

Solid if not spectacular would have been fantastic for the 1995 Mets at mid-season. The All-Star break came 69 games in, a function of the shortened season. The Mets were buried at 25-44, the third-worst record in all of baseball. Our only All-Star was Bobby Bonilla, whose persona had ventured into elder statesman territory, except for that May Saturday in Philadelphia when he a) ran through third base coach Mike Cubbage’s stop sign, b) got thrown out at third to kill a Met rally, and c) insisted to reporters that Cubbage “can kiss my ass” once told mild-mannered Mike’s side of the story (“I held him up”). Otherwise, Bonilla was being productive at the plate and less destructive than in past seasons to the club’s esprit de corps. Four years into his five-year contract, that’s really all you could ask of Bobby Bo. Still, you prefer to beam with pride rather than grimace in resignation when the lone player representing your cause in a going-nowhere year is introduced at the All-Star Game.

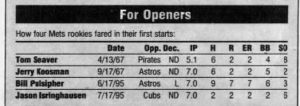

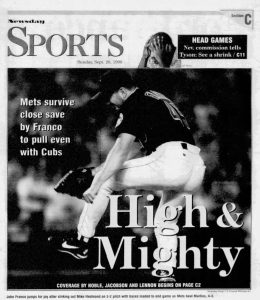

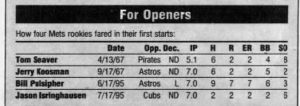

Two genuine spritzes of excitement, delivered a month apart, did burst forth from the rotating lawn sprinkler of player transactions. We didn’t even mind if our trouser legs got soaked as we strolled down the street when the news hit us. On June 17, Bill Pulsipher, 21, was summoned to make his major league debut. Pulsipher — Pulse — was the lefty starter we’d been hearing about since the year before when he was dominating Double-A. On July 17, Jason Isringhausen, 22, got the call to throw his first pitches in the bigs. Isringhausen — Izzy — was Pulse’s righty complement and the object of a swelling fan outcry to get him up here already from Norfolk, where he’d been toying with Triple-A batters. Each pitcher went seven innings in his respective introduction. Pulse’s, at Shea, were messy and the Mets lost (I witnessed it in person alongside this Jason guy I knew only from an AOL board; how exotic!). Izzy’s, at Wrigley, sparkled and the Mets won (I listened to most of it on the radio because something called The Baseball Network couldn’t be bothered to beam it into New York). For fourteen combined innings, our mood rings escaped black. For fourteen combined innings, the kids allowed us to anticipate what might be.

What actually was by the drizzly Sunday morning of August 6 had reverted to dreary, as the New York Mets sported the worst record in the National League, 35-57. The trade deadline motivated them to send Bobby Bo to Baltimore and Bret Saberhagen to Colorado. In a couple of weeks, they’d end the Brett Butler experiment and dispatch their leadoff hitter back to Los Angeles from whence he came. Izzy and Pulse were the bleeding edge of a de facto youth movement. The Mets didn’t explicitly advertise their change in direction. Nobody implored us to bring our kids to see their kids, “their” kids dressed in those not quite satisfying thin-scripted jerseys, yet that’s what I was doing on August 6. Well, no kiddies, but I did bring my wife, both of us in box seats alongside my college friend Rob Costa, by 1995 a sales rep in good standing for what would eventually be reviled as Big Pharma. Rob was a sweetheart who didn’t much care about baseball, but tickets to Mets games were one of the perks he was authorized to disperse at his discretion. He made us his clients for the afternoon.

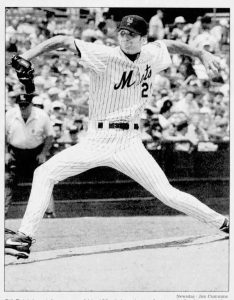

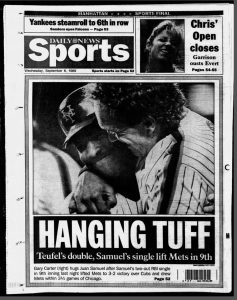

I’d been to six games since the strike ended. The Mets were 0-6 when I appeared in their midst. On August 6, there was mist, but there was also no mistaking that a losing streak was about to be broken. Third-year starter Bobby Jones gave up a first-inning run to the Marlins when Terry Pendleton grounded out to second with a runner on third and less than two out. Pendleton was a ghost of Shea pennant race past. Gloomy as the skies were, this was no day for ghosts or, for that matter, the past. Jones settled in to keep the Fish at bay through six. In the meantime, Bobby from Fresno drove in the tying run on a squeeze bunt in the second; my main Met Rico went deep to provide us a lead in the fifth; erstwhile utility infielder Edgardo Alfonzo, lately getting a chance to wrangle third base with Bonilla no longer around, chipped in an RBI in the sixth; and Jeff Kent, who never seemed to shake the boos his crummy first two months brought on, put things out of reach with a three-run homer. Jones pitched into the seventh of a 7-3 Met victory, my first since May 1, 1994.

Jones was 25, same age as Brogna. Alfonzo, or “Fonzie,” was all of 21. Kent was the senior youth at 27. Throw in Pulse, Izzy, 26-year-old Hundley behind the plate most days, 24-year-old Carl Everett around in right, maybe 25-year-old left fielder Damon Buford, who we got for Bonilla…did we have something here? Minor league slugger Butch Huskey would be promoted a couple of weeks later. He was 23. The other Oriole we received as payment for Bobby Bo, Alex Ochoa, would be up in September. “Five-tool” was the scouting report attached to this intriguing 23-year-old.

We had something here, all right. We had a young Mets team finding its footing all at once. From that gray Sunday afternoon at Shea in the company of Rob Costa forward, all the way to the end of the season, the Mets played 52 games and won 34 of them, an eight-week pace three games better than anybody else in the National League over that span and, for what it was worth, one game better than the 1986 Mets (33-19) from when they played their final 52 regular-season games. Meanwhile, Saberhagen and Butler were helping the teams to whom they’d been traded to the expanded playoffs, the same tournament that would include Worst Team Money Could Buy alumni Eddie Murray with the Tribe and Vince Coleman with the M’s. Bonilla didn’t show Baltimore October, but he won terrific-teammate kudos for pushing modest Cal Ripken from the dugout to take a victory lap at Camden Yards when Cal surpassed Lou Gehrig’s consecutive games played standard on September 6.

What was that acronym I learned from America Online? “LOL,” which by the 2010s would often be something done in the Mets’ faces when players they moved on from moved on themselves to bigger things and better situations. Yet we didn’t miss any of those veterans who wore out their Shea welcomes. We had the kids, and this old man of then 32 was bringing himself as often as possible to see them in winning action. My 0-6 start became a 7-7 final personal record, a crisp .500 in my steno pad of dutifully logged results, secured on the last day of the season when nothing could have deterred my rushing to Flushing. It took eleven innings, but the Mets beat the Braves for a series sweep. They had just swept the Reds the series prior. In August, they had swept the Dodgers, Izzy outpitching reigning rookie phenom Hideo Nomo in a sunny Sunday finale. The Braves, Reds and Dodgers were the three National League division winners in 1995. DiamondVision let us know the Mets were the only NL team to take three of three from all three flag-bearers. We were creeping into the highlights on our own merit.

The Mets’ final record in that 144-game season was 69-75. Momentum might have carried them to 81 or more wins had the pocket schedule contained its usual allotment of boxes. The upsurge was enough to catapult the Mets from fifth/last place in the East to a tie for (admittedly distant) second. We were statistically better than Florida, better than Montreal and no worse than Philadelphia, the league’s most recent pennant-winner. Give us time and we could think about taking aim at Atlanta.

I’ve rarely ended a Met year in a better mood, even if there was no ring to prove it.

by Greg Prince on 26 January 2024 4:01 pm “Yeah!”

“All right!”

“Finally!”

I can’t quote exactly, but the words above were more or less my reactions to immortality stamping its approval on the permanent records of Met icons and elevating them to the highest level visible to the general baseball public. We already knew our guys —

Tom Seaver, before posting the magic 98.84% no other starting pitcher has ever matched, in ’92;

Bob Murphy, before the Frick picked up on what he’d been saying into his mic all those summer nights, in ’94;

Gary Carter, before it could be discerned that an institutional choice between bronze logos would be necessary, in ’03;

Mike Piazza, before a fourth go-round certified him as “durable,” “prolific” and “power-hitting”, in ’16;

and Gil Hodges, after multiple generations had failed to recognize what he did and who he was, until all was remedied and forgiven in December of ’21

— were greats. Now nobody else had an excuse to not know. Our guys were Hall of Famers.

A check mark on at least 75% of Baseball Writers Association of America ballots will usher a player into the Hall of Fame. On Tuesday night, David Wright was revealed to have received 6.2% of the BBWAA vote, and I pumped a fist. I think I added a “Yeah!” despite the voting not being all Wright. It didn’t get him into the Hall à la 2024 electees Adrian Beltre, Todd Helton and Joe Mauer, and it didn’t get him within conceivable plaque gallery reach like his teammates Billy Wagner (73.8% with a year left) and Carlos Beltran (57.1% and the echo of banging trash cans fading), but it kept him in the conversation. Sometimes you can’t ask for more than to be talked about a little.

When David was in his prime, which lasted about a decade, I wondered how his Hall of Fame case might unfold. I was entitled to Mets fan bias, yet I wasn’t sure I’d be shouting to the heavens that an injustice was being done if he wasn’t collecting scads of ticked boxes when his time under the microscope came. It’s like that when you live with a player day in and day out.

David made outs slightly more than seven of every ten at-bats.

Why couldn’t have David gotten a hit there?

David was known to once in a while throw around or beneath the grasp of his first baseman.

Geez, David, c’mon!

David couldn’t lift an entire his team on his shoulders when that team insisted on weighing itself down with underachievement.

I’m mad at all of them — yes, even David.

He never put up video game numbers, but he was always the real deal. He did everything well and conducted himself better than that, still I never convinced myself he was quite on the level of a Schmidt, a Brett, a Chipper Jones, if you’ll pardon the expression. Those, to me, were Hall of Fame third basemen. I imagined some clever analytic argument would be floated on his behalf, and I could picture groupthink developing in the same way it’s evolved for players it never occurred to me were Hall of Famers when I experienced them when I watched them actually play, and, my Mets fan bias notwithstanding, I figured I’d kind of roll my eyes at the whole exercise. He’s not Mike Schmidt. He’s David Wright.

Then David’s prime screeched to an injury-riddled halt and I stopped wondering about his Hall of Fame case until the Hall of Fame released a ballot that included his name, and my prevailing Hall of Fame desire became 5 for 5: get those 5% of the votes that would keep the last Met who will ever wear 5 alive in the greater baseball consciousness for another year. Don’t let him be one and done. Don’t tell me the career of the only long-term everyday player who played every day as a Met until he physically couldn’t and never played in any other garb (besides that of Team USA) didn’t at least hint at that level. Don’t tell me nobody besides us noticed our guy, our Captain.

My desire was satisfied by a margin of four votes. Yeah. All right. Had five writers who threw him a check mark not thought highly of David’s stats or comps, or remembered warmly he was what he was as a third baseman/run producer while also being the standup guy they needed whenever they needed an honest quote, he’d be off next year’s ballot. Hanging around in the “all other” discussion every December and January carries its own burden of limited expectation and likely disappointment, but from the outside looking in, it seems preferable to being told to take your Silver Sluggers, your Gold Gloves, your All-Star selections, your quiet leadership and all the rest of your selfless persona and move along.

Less than 5% for No. 5 would have been the moral equivalent of spinal stenosis. No chance to change minds and garner a touch of momentum winter to winter. No chance to wave Scott Rolen’s name around and reason, Wright’s no Schmidt, but there was this other Philadelphia third baseman to whom he was pretty similar, and if Rolen’s in the Hall, well… No chance to be considered at all unless a Contemporary Era-type committee became intrigued by his case down the road, maybe far down the road, when “contemporary” implied an era way beyond his. No chance that wasn’t random that David Wright would be mentioned by anybody outside the walls of Metsopotamia, where we don’t require anybody else’s stinking validation to tell us who our greats are. Yet it sure is nice to know that slightly more than a bare minimum of professional baseball observers remembered there was once a lifetime Met who was on a path that, had all continued in decent health, could have led to Cooperstown.

by Greg Prince on 22 January 2024 1:00 pm We have reached the third installment of MY FAVORITE SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT. I can’t swear it’s the middle installment, but below you’ll find the middle portion of the list: the seasons just before the median (Nos. 33-29); the median season (No. 28); and the seasons just beyond the median (Nos. 27-23). As is implied by reaching the center square and adjacent environs, the overall Mets experiences here are veering more toward the explicitly positive than they were at the outset of this journey. Of course if you’re a Mets fan, you understand that even years whose statistical output appears splendid on the surface may not resonate as enchanting when you remember what they were actually like to live through. This explains how seasons with 88 or 92 wins will rank well below seasons with 41 or 68 wins. To be clear, winning beats losing 162 out of 162 times. Nevertheless, there are winning seasons and there are favorite seasons. They don’t always meet in the middle. My desire to say something nice about what I perceive as not altogether nice Met days remains, yet I stowed the kid gloves for certain of these campaigns and let my lingering discontent seep where appropriate. If a season encompassed 88 or 92 wins yet lands in the lower half of a ranking of favorites, I have to think it brought its infamy upon itself.

As in Part One (Nos. 55-44) and Part Two (Nos. 43-34), I have striven to mine my rooting subconscious and share some memories and insights that haven’t come up in these pages before. That gets more challenging as the countdown goes on, given that over the past nineteen years of blogging, I’ve shared a lot, particularly about the seasons I liked and loved most (not to mention the seasons that were in progress between 2005 and 2023). A person has only so much past, even one who goes back as far as I do. If bits and pieces begin to sound familiar to you as a regular reader, first off, thank you for reading regularly, and secondly, I hope my attempt to craft new spins adds a fresh element.

***33. 2007

I don’t know much about gambling per se, but here’s a piece of probably profitable advice: the next time the Mets are coming off a playoff year, bet the under the year after. The Mets have made the postseason ten times. Ten times, the Mets have posted a lesser record the year after; on average, their won-lost mark is minus-13 versus the more satisfying and successful season preceding it. I suspect that’s what the wagering community refers to as a lock. Not that precedent predicts everything, but 2007, when the Mets couldn’t maintain their division-winning pace of 2006, should have taught us once and for all that not only won’t the year after be quite (or nearly) as good, it won’t feel as good. Given a positive trendline, we’ll never stop trying to convince ourselves it feels comparably great — we might even be brimming with confidence as late as the middle of September — but don’t bet it will turn out well either mathematically or experientially.

32. 1987

“You know what it was like?” I remember telling a friend that November. “It was like having a nagging sinus headache all season.” I’ve been forever prone to sinus headaches that almost but don’t completely go away no matter what I take for them. I can operate like a functioning human being if I must, even manage to have some facsimile of fun in the intervals when it seems to recede, but until it’s completely gone, I know something’s off and I find myself pressing an index to the top of the bridge of my nose on whichever side is piercing most. It doesn’t help. What really helps is holding an index finger high in the air like I did the year before 1987.

31. 2001

For four-and-a-half months, 2001 provided a template for cruddy 2023. Then, as August grew late, 2001 began to echo 1973. Then the second Tuesday in September happened, which had nothing to do with baseball, yet there were the Mets, resuming their roll when play unpaused the Monday after that Tuesday, on September 17; and coming home to New York on September 21; and Mike Piazza hits a homer; and they win that night, and they win the next night; and they’ve picked up ten games in the standings in a five-week span; and you gotta believe something way bigger than a charge-from-behind pennant race is happening at Shea Stadium. Then, in the shadow of two fallen towers, the Mets find a way to break whatever corners of our heart aren’t already broken not once (Braves 5 Mets 4 in 11 on September 23), but twice (Braves 8 Mets 5 via a walkoff grand slam on September 29). Then, save for Mike’s incandescent swing, the entire season is memory-holed. I’m here to tell you it did happen. It was real and it was almost spectacular.

30. 1978

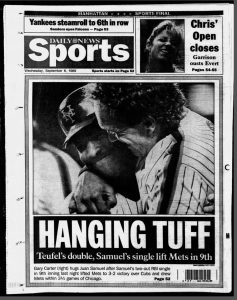

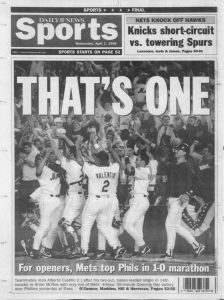

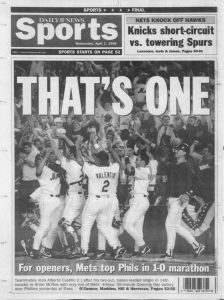

On April 23, the back page of the Daily News led its sports coverage with a headline trumpeting the Mets’ capture of the top spot in the National League East, something NOBODY was expecting at the outset of the second year of the Grant’s Tomb era. Staring at it when I was fifteen, my mind worked like Lisa Simpson’s years later when she met a cool kid who paid her hat a compliment. “Scanning for sarcasm…it’s clean!” I liked the headline so much, I clipped it and taped it to the door of my bedroom closet. The News that Sunday wasn’t messing with me. Jack Lang may have been shaking his head while he typed it in the Wrigley Field press box, but his lede was as sincere as it was accurate: “The first place Mets! Roll that around on your tongue for a while and see how it sounds.” Manager Joe Torre affirmed, “It sounds beautiful to me, just beautiful.” The explanation that followed in the wake of the Mets beating the Cubs was just as mellifluous: “The victory, combined with the Expos’ sweep of the Phillies in a twinbill, gave the Mets first place all by themselves.” Cripes, Lang even referred to Mardie Cornejo and Skip Lockwood as “co-aces of the bullpen”. Mardie Cornejo! All that was missing was praise for the blue and orange trimming the team had sewn on to the cuffs of its sleeves for ’78, though in those days New York’s Picture Newspaper didn’t publish in color. On April 23, the back page of the Daily News led its sports coverage with a headline trumpeting the Mets’ capture of the top spot in the National League East, something NOBODY was expecting at the outset of the second year of the Grant’s Tomb era. Staring at it when I was fifteen, my mind worked like Lisa Simpson’s years later when she met a cool kid who paid her hat a compliment. “Scanning for sarcasm…it’s clean!” I liked the headline so much, I clipped it and taped it to the door of my bedroom closet. The News that Sunday wasn’t messing with me. Jack Lang may have been shaking his head while he typed it in the Wrigley Field press box, but his lede was as sincere as it was accurate: “The first place Mets! Roll that around on your tongue for a while and see how it sounds.” Manager Joe Torre affirmed, “It sounds beautiful to me, just beautiful.” The explanation that followed in the wake of the Mets beating the Cubs was just as mellifluous: “The victory, combined with the Expos’ sweep of the Phillies in a twinbill, gave the Mets first place all by themselves.” Cripes, Lang even referred to Mardie Cornejo and Skip Lockwood as “co-aces of the bullpen”. Mardie Cornejo! All that was missing was praise for the blue and orange trimming the team had sewn on to the cuffs of its sleeves for ’78, though in those days New York’s Picture Newspaper didn’t publish in color.

The season was fifteen games old. The Mets’ grip on first place didn’t survive the weekend.

When 1978 was much older, on August 10, the News, the Post and the Times went on strike for what amounted to the rest of the season, so I didn’t get to read what would have been presumably much more cynical coverage of the Mets’ predictable fall from grace. There were a few strike papers available — the City News, the New York Daily Press and the New York Daily Metro stand out in my recollection — but their Met coverage tended to be brief, derived from wire reports and usually a day late; they’d have Tuesday home game results in print on Thursday. In 2018, Tom Verducci wrote at length about how the 1978 Yankees coalesced for their historic comeback because they had less local print media magnifying their every move. Overnight, scrutiny and pressure simultaneously diminished. “The suburban papers were there,” then-PR director Mickey Morabito remembered for Verducci. “They wrote game stories, and they went home. It was like a vacation.” As unfortunate as that byproduct of the job action was, I can sort of relate. The only 1978 Mets headline that stays with me, regardless of their last-place finish, is METS TAKE 1ST PLACE.

29. 2010

Between April 19 and July 27, I attended fourteen games at Citi Field. The Mets’ record in those contests was 14-0, meaning I was 14-0, easily my most incredible streak of luck in all my years of game-going. The Mets were pretty good at home in that span without me, going 15-12 (versus an abysmal 18-29 road record), but they weren’t utterly incapable of losing like they were when I was around. Somewhere along the way, the Mets’ A/V squad adopted a song called “Uprising” by a band called Muse as their would-be “L.A. Woman” for 2010. If the Mets won at home, the loudspeakers would blare it following a requisite dose of “Takin’ Care of Business”. I heard “Uprising” in regular rotation whether I wanted to or not. Given what it represented, I wanted to hear it in a loop and sort of did. I couldn’t tell you what they played after losses between April 19 and July 27, immune as I was to being there for such unfortunate events. The chorus of “Uprising” ended on a message that spoke to what Muse guaranteed was to come: We will be victorious. Maybe they should have stuck with what had just happened rather than trying to be fortune-tellers; even a fan who was going 14-0 never presumed a win in advance. There was also a line about watching our flag ascend. Alas, no banner other than the star-spangled one rose in Flushing in 2010. Still, when I hear “Uprising” these days, which only happens if I click on the iTunes playlist I complied for myself that season, I’m verifiably unbeatable.

28. 2014

I would hope John Mellencamp doesn’t mind that I’ve retroactively adopted the lyrics from “Cherry Bomb” to describe the year before the Mets won their most recent pennant: “We were young, and we were improving.” I wasn’t really thinking “hey, we are young, and we are improving” as 2014 dragged along, because a) the Mets’ roster included 40-year-old Bobby Abreu and 41-year-old Bartolo Colon, and b) the Mets fell below .500 on May 7, never to rise above it again. We were stuck in a cycle of mediocrity dating back to the opening of Citi Field. Never fewer than 70 wins, never as many as 80 wins. The 2014 Mets topped out at 79. But they also included within their number initially unheralded righty Jacob deGrom (26) earning the Rookie of the Year award; fellow starter Zack Wheeler (24) getting the hang of disposing of innings in a timely manner; revelation reliever Jeurys Familia (24) setting up repurposed closer Jenrry Mejia (24), each of these talented pitchers throwing to an increasingly confident Travis d’Arnaud (25); Juan Lagares (24) presiding over funerals for fly balls in center so consistently that he was awarded a Gold Glove in his first full season on pasture patrol; and less smooth infielder Wilmer Flores (23) brandishing a bat that made a person occasionally stop worrying where the kid from Venezuela’s mitt would fit best. On their better nights, I began to think we had something here. Their better nights leaned to too few and far between, so I didn’t think it that often. Some years it’s hard to see what’s coming together when there’ve been so many years when everything falls apart.

27. 1976

Had I been a less discerning 13-year-old, I’d probably maintain gauzier nostalgia for 1976. A sampler of signifiers pop like the National League centennial patches and special-occasion pillbox hats worn by the Mets that year and only that year. Mike Phillips hit for the cycle. John Milner swatted three grand slams. Bruce Boisclair became Bruce Boisclair. Good ol’ Kooz finally won 20. Dave Kingman was at his Dave Kingmaniest. Brooklyn’s own Lee Mazzilli came up in September and hit a home run that effectively knocked the second-place Pirates from contention. For the very first time in my life, I saw Tom Seaver pitch in person (fittingly enough with no run support in a 1-0 loss). And from 1970 through 1983 inclusive, no Mets team won more games than the ’76 bunch: 86. What’s to be discerning about at that age? Had I been a less discerning 13-year-old, I’d probably maintain gauzier nostalgia for 1976. A sampler of signifiers pop like the National League centennial patches and special-occasion pillbox hats worn by the Mets that year and only that year. Mike Phillips hit for the cycle. John Milner swatted three grand slams. Bruce Boisclair became Bruce Boisclair. Good ol’ Kooz finally won 20. Dave Kingman was at his Dave Kingmaniest. Brooklyn’s own Lee Mazzilli came up in September and hit a home run that effectively knocked the second-place Pirates from contention. For the very first time in my life, I saw Tom Seaver pitch in person (fittingly enough with no run support in a 1-0 loss). And from 1970 through 1983 inclusive, no Mets team won more games than the ’76 bunch: 86. What’s to be discerning about at that age?

Well, there was all that dust the Mets were left in by the Phillies. Pittsburgh wasn’t the only team that couldn’t make a successful run. Our third-place finish by this point was a little too familiar and that 86-victory total, while mathematically more than every Mets club that wasn’t from 1969, was practically as backloaded as Shohei Ohtani’s contract. We were 52-55 on August 2, 34-21 the rest of the way, better than everybody in baseball — 34-16 before an 0-5 sneak preview of 1977 ended the schedule. Even that badge of out-of-it honor was tarnished in May the next year in the wake of the Mets’ godawful start. Speaking for the board of directors, John Payson thought it necessary to visit the clubhouse and read to the players a statement of support for embattled chairman M. Donald Grant (an inversion of Grant telling the players four years earlier that management still believed in them). Within his declaration, Payson reasoned, “Our team played very well after the All-Star game last summer,” plus 1969 and 1973 went so swimmingly. “The Mets have had many early-season slumps and have pulled out of them by playing as a team” was his version of go get ’em. The sparkling conclusion to 1976 had been weaponized in the name of preserving the status of the man who was about to trade Seaver. So thanks for ruining that, too.

26. 1972