The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 20 June 2024 11:10 am Being a fan is inherently ridiculous.

Two weeks ago we were collectively rending our garments because the Mets were painful to watch and we were killing time waiting to a) see what they got for every upright body at the trade deadline; and b) complain about seeing Pete Alonso in the togs of the Mariners/Cubs/Giants/What-Have-Yous.

Then came the Grimace era, which while barely a week old saw us think the Mets had figured everything out and were unbeatable — perhaps no more so when they coolly came from four runs down to shock the Rangers, perhaps by way of tribute to the now late, eternally great Willie Mays.

Wednesday night this rickety tower built from giddiness and recency bias and hubris all came crashing down, as the Mets suddenly looked very much like the Mets of two weeks ago vintage, failing to win an eighth straight and leaving Grimace with a pang in his big purple heart.

Defeat had a lot of fathers. There was Edwin Jimenez‘s improv strike zone, which was no help to a suddenly wild Sean Manaea in a profoundly irritating first inning. (While Jimenez was definitely bad, a bases-loaded HBP on an 0-2 count isn’t one you can pin on the umpire.)

The Mets fought back against Andrew Heaney, whose significant other really should tell him to lose his living-under-a-bridge beard, with Alonso’s homer to center giving them a 3-1 lead. But they gave it back in the sixth, with Sean Reid-Foley allowing the Rangers to tie it while looking out of sorts, prompting Gary Cohen and Keith Hernandez to speculate if something might be physically wrong. Something definitely wrong in that inning was the defense: First Starling Marte overthrew the cutoff man and Alonso made a weak throw home, and then Mark Vientos couldn’t corral a hot grounder in the hole.

The Rangers had tied it, and Drew Smith allowed them to untie it in the seventh, serving up a two-run homer to a slumping Leody Taveras. While I’ve never dubbed Smith a Jonah, I’ve also never trusted him, unless it’s to give up dingers every time a Mets manager decides he’s worthy of moving a step up the bullpen ladder. Giving up home runs is what Smith does; I hurled poorly sourced and unfair imprecations his way and hoped the Mets would come back, though I had an uneasy feeling that particular well of luck had run dry.

As indeed it had. The Mets came up in the ninth needing a bloop and a blast and got neither: Marte grounded out, Vientos got himself out with an overly aggressive AB, and Francisco Alvarez fought through a tough AB but grounded out.

You can’t win ’em all, a wise person once said — a warning probably first heard in Mesopotamia, soon after some bunch of marvelously Guillorme-bearded Babylonians decided to venerate Ishtar with a diversion involving a ball and a stick. It’s a warning we briefly thought no longer applied to us. Now, once again, we know better. Stupid real life!

by Greg Prince on 19 June 2024 10:14 am He who has led baseball in every meaningful way for generations has been reported to have passed away. If these reports prove accurate, protocol therefore demands the flag be lowered to half-staff, then ball must be played like it’s been played only once before — from 1948 to 1973. Play it like it was played in Birmingham; in Trenton; in Minneapolis; in Manhattan; in San Francisco; in Flushing. Play it like it was played everywhere Willie Mays called home, which collective experience specifies was every ballpark he ever graced. Willie competed in the uniform of just a handful of organizations, but his brilliance belonged to every fan. So to honor him, wherever you are and whomever you root for, please remove your hat, bow your head, picture No. 24 amid your reverent moment of silence, and then play ball. Play with style. Play with heart. Play with innate intelligence that divines every nuance of the game and use what you know to your and your team’s full advantage. Play with all the ability in the world if you have it (Willie did) or all the ability you can muster (Willie did that, too). Play with joy. Work relentlessly at being the best, but don’t give the impression it’s work. Play ball.

On Tuesday night, the same night it was announced Willie Mays had moved on, the last team for whom he played professionally displayed the kind of joie de ball that made the man immortal in every sense we baseball-loving mortals can fathom. The New York Mets trailed the Texas Rangers, 6-2, after five innings, yet came away the winners in Arlington, 7-6, posting their seventh consecutive victory. They hit; they hit with power; they fielded; they threw; they ran; they understood what needed to be done; and they did it. Maybe their caps flew off in the process. If it wasn’t a conscious tribute to the National Pastime’s head of state, it was as appropriate a performance as one could summon to leaven the aftereffects of the shocking bulletin we’d been reluctantly delivered.

Willie, they said, died at 93. It’s shocking regardless of age. You would have bet even money — an action MLB is cool with these days — that Willie was the one person who would defy standard actuarial odds. Ninety-three? Watch Willie go for a hundred and then keep going. Based on everything we saw and read since he entered our consciousness, he may be deking us at this very moment just so the trail runner can take third on the celestial relay.

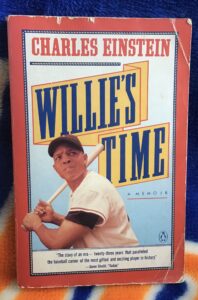

If this really is it, Willie still isn’t gone. Baseball is Willie’s game. Not was, is. We’ve lived in Willie’s time for so long, it seems impossible to reset our watches. There was baseball before him. There’s been Baseball with a capital Willie since. He linked every era so seamlessly that you’d almost think they’ve flowed as one. I’ve never existed a day when Willie Mays couldn’t be identified as the greatest ballplayer alive. I doubt I’m ready to start now. If this really is it, Willie still isn’t gone. Baseball is Willie’s game. Not was, is. We’ve lived in Willie’s time for so long, it seems impossible to reset our watches. There was baseball before him. There’s been Baseball with a capital Willie since. He linked every era so seamlessly that you’d almost think they’ve flowed as one. I’ve never existed a day when Willie Mays couldn’t be identified as the greatest ballplayer alive. I doubt I’m ready to start now.

Willie Mays came to New York in 1951 and put down psychic roots that outlasted both the Polo Grounds and Shea Stadium. Both parks were better off for his presence. The New York Giants, as proud and historic a franchise as ever was, personified past glory before Willie showed up. Willie made them vibrant and contemporary and winners. They left town, anyway. There are many reasons to fondly recall the New York Giants of 1883 to 1957. The first and sometimes only one people know in this century is Willie Mays.

We weren’t done cheering for Willie just because his jersey didn’t say NEW YORK on it when he returned to the old neighborhood or brightened the new environs. No “visiting” player was ever as thoroughly or sincerely or consistently embraced as Willie Mays was when he was technically a Met opponent for a decade. That’s because he was never more than technically a visitor. How could he be? He’d never stopped owning New York.

It’s wrong that the Giants ever departed New York. It’s wrong that Willie had to be anything but a Giant. It’s absolutely right that Willie Mays was a New York Met. There’s an awful lot of “you had to be there” to explain what it meant to see No. 24 rendered in orange and blue and Willie elevating the color scheme to a whole new level in 1972 and 1973. You had to know a little something about where Willie had been prior to San Francisco and how New York couldn’t forget him. Even if you were a kid of nine or ten, you got it and you were all in on what was happening. Willie Mays was here in front of you, not for a series, but for a season, then another one, then the postseason that followed. You knew it was late for him as a player. You heard it wasn’t the same as it had been when he arrived twenty-some years earlier. You, quite frankly, didn’t care. You got Willie Mays in your midst. You were blessed by the glimpse and you never forgot it.

When his career was over, a trope emerged that 42-year-old Willie Mays had stayed in the game too long. The next 51 years revealed Willie could stay as long as he liked, wherever he liked, however he liked. By outliving every ballplayer considered something akin to his peer, appreciation of Willie Mays as singular revived and amplified. The Giants, despite their sin of going west, took care to burnish his vast legacy. The Mets, once the proper people had their say, threw in their 24 cents on preserving his place in history. Film clips survived. Some were in black and white. Those that were in living color turned grainy. If you were shown video evidence of what Willie Mays was all about, you tended to see just so much. Unless you were regularly in those ballparks he made his, you could only imagine what he was really like to watch every day in his extensive prime. You could only listen to what was said about him doing the impossible. You could only read the breathless accounts and attempt to comprehend the breadth of his statistics. You didn’t get a nonstop stream of Willie Mays content as you would have had he come along in our time.

Maybe our loss. Probably his gain. This way he’s a legend with just enough evidence to back up the stories we’ve had handed down to us and take pleasure ourselves in handing down again. Willie Mays had all the tools. None surpassed his timing.

by Jason Fry on 18 June 2024 10:50 am I didn’t expect a giddy stretch related to the 2024 Mets, and yet here we are.

I was playing mini-golf and eating ice cream, meaning I was late to my assigned duties (sorry not sorry) and yet was only mildly surprised to find it was Forces of Good 7, Defending But Currently Not So Hot World Champions 0. A David Peterson non-slider immediately made it FoG 7, DbCnsHWC 2 and I felt a smidge of guilt, but no matter; as I excavated the interior of my cup for beaded-up caramel, Brandon Nimmo restored momentum order and it was 9-2.

9-2 on the way to 14-2, with luckless Andrew Knizner pressed into service before the end. The Mets pounded out 22 hits, 17 of them singles, ambushing Jon Gray early and relievers late. (Knizner was unscored upon, because baseball.) Four hits for a suddenly incandescently hot Francisco Lindor (in two-thirds of a night’s work, no less); three for Nimmo, Pete Alonso, Mark Vientos and Francisco Alvarez; two for DJ Stewart including a put-em-on-notice three-run homer in the second; at least one for everyone in the startling lineup save Tyrone Taylor, who somehow missed the memo.

By the end everyone was a little giddy. Gary Cohen was explaining to Keith Hernandez how Mets fans want carnage, not close-game drama; Steve Gelbs was recounting a delightful story about chatting with Max Scherzer and a random kid in the stands; and Scherzer, now in Texas garb, was riding Alonso from the enemy dugout for taking a walk against Knizner. After the game, Gelbs ambushed Nimmo with a query about whether the Mets attribute their winning streak to Grimace throwing out the first pitch last Wednesday. (If you’re not Very Online, it’s a thing.) Nimmo, expecting another round of arglebargle about approach and teamwork and one day at a time, was tickled to be caught off-guard.

Everything’s fun when you’re atop the world, whether you attribute said status to unlikely first pitches, team meetings, sunspots or having sacrificed a pure-white lamb on a blood-soaked obsidian altar beneath the last new moon of spring. (Let’s hope it’s not that last one; sounds kinda mean.)

I’ve watched enough baseball and internalized enough of its maddening ebbs and flows to know not to think too hard about these stretches; it’s simultaneously true that no logic underpins them and that whatever logic is assigned to them anyway can become its own engine of further success. You just enjoy them, knowing from hard experience that the karmic wheel is still turning and so the view from the top is to be savored as long as it lasts.

by Greg Prince on 17 June 2024 9:53 am For a team that has posted six walkoff wins to date, it’s not a bottom of the ninth or eleventh that ranks as the Mets’ most satisfying half-inning of the year (and it’s certainly not a tenth; the Mets are 0-6 in ten-inning games). We have to hand this highly specific honor to the bottom of the eighth from Sunday, a demi-frame that didn’t even involve coming from behind or breaking a tie.

Rewind slightly to the top of the eighth, which began with the Mets ahead, 7-2, itself a satisfying score. The Mets were in command from the moment Pete Alonso unleashed a three-run Polar blast in the bottom of the first, vaulting the Mets ahead, 4-1, the capper on four consecutive Mets reaching base, beginning with Francisco Lindor’s leadoff homer. The Padres had scratched out a run in the top of the first, but that dent on Tylor Megill’s ledger felt distant once Pete went deep. By the time Megill gave up his second run, in the fifth, the Mets had added three more of their own off San Diego’s Dylan Cease. Indeed, the action unfolded to ensure a happy birthday to all you fathers out there.

Then came the top of the eighth, when unfolding morphed into unraveling. Goriest details will be withheld to spare the squeamish. Suffice to say that as 7-2 shrunk to 7-6 at Citi Field in the present, somewhere in the mind’s eye, Derek Norris was going 5-for-5 and Justin Upton was licking his chops at the sight of Jeurys Familia. The stormy Padre uprising of July 30, 2015, notorious as it remains in the darker recesses of Met lore, at least includes the saving grace of seeding the ground for a much brighter Met redemption arc — Cespedes! Flores! Nats beware! — barely 24 hours away.

Somnambulant San Diego’s all-at-once wakeup call in the top of the eighth inning of June 16, 2024, offered no obvious redeeming features in the moment, and it was hard to discern any pony hiding in the pile of horse manure wrought by Starling Marte not catching a catchable fly ball; Jake Diekman showing terrible control whether throwing to second or home; and Drew Smith’s pitches serving as piñatas. Harrison Bader leaping in the air to nab a line drive that was ticketed for over his head and Marte firing to the plate with precision at least kept things from getting massively worse. They were already pretty bad.

The Mets’ five-run advantage had slimmed to one. The rare sense that the Mets were playing a baseball game and being the definitively better team within it had melted. Across the first seven innings, I found myself perceiving these Mets as actually pretty good. It took only 70 games to arrive at that conclusion. The previous two weeks’ worth of mostly winning was pretty swell, but struck me more as a delay of the inevitable return to 2024 form. I seem to have reached the stage in my lifelong fandom that might be labeled the Missouri phase. You want me to Believe? Don’t try to impress me with a win here, a win there. Show me you’ve got something more up your pinstriped/black/royal blue/slate gray/road gray sleeve. When the Mets are relentlessly subpar, brief intervals of competence tend to annoy me more than all-out ineptitude does. Why are you wasting my time trying to convince me you don’t suck? We both know you do. Just get it over with.

Ah, but then came the bottom of the eighth, when, à la Norris and Upton in ’15, whatever torture the Padres had just put us through turned out not to matter in the scheme of things. Luis Torrens homered. The lead was two. Jeff McNeil doubled. Harrison Bader singled. McNeil went to third. Bader stole second. Lindor walked. Brandon Nimmo singled home McNeil. The lead was three. Invincible J.D. Martinez somehow struck out with the bases loaded, but Alonso sure as hell didn’t. Pete singled to score Bader and Lindor. The lead was again five. This evenly divided eight-run eighth wasn’t quite the eleventh inning of June 30, 1979, when the Mets scored six in the top half at Wrigley Field only to have to withstand five Cub tallies in the bottom half, but it was close enough to make me remember the Mets and Cubs once combined for eleven runs in an eleventh inning, which set one of those records it never occurred to me existed.

My Dale Murray flashback dissipated, returning me to the contest we were no longer letting slip away. Did we really just answer four daggering, staggering Padre runs with four everything’s-gonna-be-all-right runs of our own? We did. Did the Mets simply decide via their actions that they weren’t going to completely blow a ballgame after almost doing so? They had. The Mets hadn’t sent a home crowd home happy on the third Sunday in June since Jacob deGrom homered on their behalf — were we not, for a change, going to end our Father’s Day in a collective grimace? We were not. Happy birthday, everyone.

An 11-6 lead and victory that wound up more fulfilling that holding onto the 7-2 edge ever would have been tells us it all worked out beautifully, save for confidence in relying on Diekman or Smith and Marte’s sense of right field geography. The Mets swept the Padres in a three-game series for the first time since we paused our giddy march to the 2006 division title just long enough to applaud like hell for Mike Piazza in a strange uniform. The Mets ended a six-game homestand with a 5-1 record, all five of the wins being their last five games, which suggests this is a team on a bona fide roll. That National League Wild Card jumble that encompasses most every band of mediocrities and their likely fatal flaws? We’re kind of in that mess for something approaching real, a mess much preferable to the one we’re usually in. It would take seven pretenders sneezing and the Mets tiptoeing by amid the cacophony of gesundheits to transport the Mets meaningfully up the standings, but that’s what the rest of the season is for. Ninety-two games remain. Suddenly, I don’t hear myself telling this team to just get them over with.

It ain’t exactly You Gotta Believe, but it’s definitely something different from what I’ve grown accustomed to thinking.

by Jason Fry on 15 June 2024 10:10 pm Happy teams, like Russian families, are all alike — and somehow the Mets are a happy team again.

That happens when you win four in a row, when J.D. Martinez is locked in, when Brandon Nimmo collects two RBIs, when Francisco Lindor pulls off an eye-popping play at shortstop, when Jose Quintana actually throws strikes and gets rewarded for it, and when the relief corps does its job.

I mean, what’s not to like?

Martinez is ridiculously hot right now, and it’s fun to finally see the deadly, professional hitter we were promised now that the rust of a late start is shaken off. Granted, it would be nice for some other Mets hitters to step up — before Nimmo’s eighth-inning RBI single Martinez had been responsible for seven of the Mets’ last eight RBIs — but that’s criticizing the brush strokes on a W after weeks and weeks of not seeing enough of that letter.

I’m still far from convinced that the Mets are any good, and seeing them part of a National League scrum shoving and elbowing for a wild-card spot leaves me grousing about too many wild cards instead of daydreaming about October. But they’re at least watchable again, with a certain seriousness of purpose and crispness of play that was galling in its absence. And that’s welcome — the season is too long to spend it mad at your baseball team.

We just arrived on Long Beach Island for our annual beach week, and between driving and attending to various logistics I lost track of the start time. So it was that I wound up riding a bike down an LBI boulevard with MLB Audio burbling out of the cellphone in my hand, knees pumping just fast enough to keep the bike moving beneath a perfect sunny sky. The Mets hadn’t done anything wrong yet (and basically wouldn’t all day) and I listened to Howie Rose painting the word picture and thought, This works. This works just fine.

Would that it could always be this way. But you take every day you’re given.

by Greg Prince on 15 June 2024 12:40 pm In the sixty-eighth game of the season, our Metsies gave to us…

Sixty-Five Minutes of Waiting: The forecast in Queens promised downpours Friday night, and the downpours were indeed delivered. The only ones that delayed play came before the first pitch, which follows a 2024 pattern. Five times this year the Mets have played ball after a tarp covered the field at their scheduled start time, yet to this point, they haven’t endured a single in-game rain delay. Clear skies are considered a lock for the rest of this weekend, followed by three games in a stadium with a retractable roof. Feeling pretty good that I haven’t jinxed anything.

Nine Averages Bracketed: Nobody in the Met lineup finished Friday night hitting as high as .300, but neither did any of our on-and-off offense-providers leave Citi Field batting less than .200. If a third consecutive win is what an average offensive team can produce, then by all means LGM (let’s get middling).

Eight Places Spacing: After topping the San Diego Padres, 3-2, Mets are a mere three games from a Wild Card slot, and have to pass only St. Louis, Cincinnati, San Francisco, Arizona, Pittsburgh, Washington and Chicago to claim it. Traffic can be a real hassle in these parts.

Seven Spirits Spooking: I count seven Friars from Friday night’s box score who were members of San Diego’s 2022 squad, five of whom participated in that October’s dreadful National League Wild Card Series, all of which transpired in Flushing, little of it to positive effect. Sooner or later, associations with postseason debacles fade, and you can look at a once-grudgeworthy opponent as just another guest in your ballpark. I’m not quite there yet where the sight of the Padres at Citi is concerned. Mostly it was the brown and yellow trim on the uniforms more than any given foe that inflicted me with chills twenty months later, though. to be fair, those threads mainly made me think of how best to adorn a Cuban sandwich.

Six Ballgames Under: The 31-37 Mets are as close to .500 as they’ve been since they sat as the 21-27 Mets 24 days ago. It’s something to be proud of only when it’s recalled that less than two weeks ago they wallowed at eleven games under. Progress is relative.

Five Golden Innings: Sean Manaea’s recent backsliding — eleven earned runs total in two decidedly non-quality starts — reversed itself. Sean pushed himself into the sixth, allowing only a solo home run to rookie phenom Jackson Merrill (he’s certainly been phenomenal this week). Manaea’s final hitter was Luis Arraez. Arraez nicked him for a base hit. Arraez nicks everybody for a base hit. Back-to-back-to-back evenings of starters not necessitating overly quick hooks is a recipe for not losing. Sometimes it even leads to wins for both the team and its starting pitcher.

Four Hits Sufficing: The Mets pulled out their victory Thursday night by making the most of three hits, the last of which was the quintessence of unpiddling. On Friday, the attack grew frisky with four whole safeties. Two occurred in the same inning; one of those was a double that brought home two runs, thanks to a walk setting that particular table. Four hits or fewer have been enough to manufacture a win on 173 occasions in their 63-year franchise history. We’ve just seen two of them in a little over 24 hours.

Three Halting Runner: Did your eyes deceive you when, as Adam Ottavino pitched, Arraez took off from first and was cut down on a throw from Francisco Alvarez to Jeff McNeil? They did not. We’ve seen the National League and its counterpart run wild on Ottavino; we’ve seen Alvarez throw out nobody; and we’ve seen McNeil drop the baseball in the process of tagging, yet this trio teamed up to actually erase a Padre from the basepaths. OK, so it took Luis oversliding second to assure this outcome, but that’s his problem.

Two Initials Raking: J.D. the DH was the HR hero the night before, and it was his 2B that provided the pair of Rs the Mets posted on the scoreboard Friday en route to their 2-1 W. A cynic might observe Martinez is the only Met driving anybody in these days. A cynic should go outside and check to see if it’s raining.

One Closer Closing: After Ottavino, Jake Diekman and Sean Reid-Foley caused no discernible tsuris in relief of Manaea, who was gonna protect our one-run lead going to the ninth? Who else but Edwin Diaz? So what if he pitched the night before? He’s back, baby! He’s back in the save column for the first time since May 6, at any rate, and he’s back on speed dial as the first option for Carlos Mendoza as long as Sugar’s not been overused. Edwin’s plenty rested. Give the man some leads. We’re brimming with confidence when he appears. Well, not overcome by dread. For Mets fans amid a one-run lead heading to the ninth, to not be overcome by dread is to brim with confidence.

by Jason Fry on 14 June 2024 11:51 am Mets Classics showrunner, slow your roll.

Thursday night’s game against the Marlins ended on a blissful note, but said blissful note was first heard and completed in the very last minute of the game. The previous 144 minutes? They were nonstop squealing and blatting, a baseball cacophony alternately dull and unpleasant to the ears.

The Mets didn’t hit. Not just as in they weren’t hitting against a semi-anonymous rookie, in this case 24-year-old Roddery Munoz, but as in they didn’t even have a hit until the sixth. Munoz left pretty much everything in the middle of the plate and the Mets hit pretty much everything right at Marlin defenders. Getting undone by hurlers still wet behind the ears has been a Met problem for decades — somewhere Chris Nabholz is cackling — but it’s always puzzling and usually at least mildly infuriating. Fortunately, Skip Schumaker decided six innings from Munoz was enough, despite his pitcher looking like he had at least another inning in him in terms of pitch count. Schumaker obviously had information not disseminated to my couch, so I’ll forgo further commentary; suffice it to say no one in orange and blue or swearing allegiance to those colors was sad to see Munoz go.

Luis Severino, on the other hand, had a baffling outing. The results were fine bordering on sparkling — six innings blemished only by a Jake Burger solo homer — but the process by which those results were obtained was off-kilter and annoying, with Severino missing his spots, losing the strike zone and constantly pitching from behind. He was helped out by a key double play as well as the Marlins’ chronic lack of discipline, but it still felt like disaster was only a step away.

And it was the Marlins. If you’re a longtime reader you probably know that I detest the Marlins to a mildly worrisome degree and think baseball would be better if this misbegotten franchise were moved elsewhere and rebranded, or better yet contracted and replaced, with the world’s population forbidden to speak of them ever again under penalty of torture. Watching the Mets play badly is never fun, but it’s particularly hideous when they’re playing badly against the Marlins.

Besides the above jeremiad, I’ll note that the Marlins are haphazardly constructed, poorly coached, and their clubhouse culture has been the stuff of raised eyebrows for generations, with Jazz Chisholm Jr. the latest example of a talented player to underperform his potential due to a lack of mentors and accountability. Lest the horse become too high, of course none of this has stopped the Marlins from outpointing us in numerous years, and last night it was Chisholm who gave the Marlins a key insurance run, homering off Drew Smith.

(Granted, surrendering homers is what Drew Smith does. When it happened I just flipped a hand in the air in mild disgust.)

The Mets looked poised to erase a 2-0 Marlin lead in the bottom of the seventh, loading the bases with nobody out behind a pair of walks sandwiching a J.D. Martinez double. Anthony Bender went to 3-0 on Starling Marte, but Marte hit a room-service grounder to third, and the Mets exited the inning with just a lone run scored. I swear the Mets are at their least dangerous with the bases loaded and nobody out, and it makes me insane.

Sean Reid-Foley held the fort in the eighth and Edwin Diaz returned to at least semi-critical duty in the ninth, showing a peppier fastball even if the sliders still looked to me like they needed some work. That left the Mets facing Tanner Scott, who looked untouchable strangling them two nights earlier, but at the cost of a lot of pitches.

(This is called foreshadowing. Let’s just pretend I did it more artfully.)

Down a run in the ninth, one of course hopes for the trademark bloop and a blast, though one will also accept a walk, some frittering around ahead of a stolen base and that blast. Francisco Lindor supplied the walk and the steal, Brandon Nimmo looked not exactly himself in striking out, and up came Martinez — who, oddly, had 320 career homers on his ledger, none of them a walkoff. The lesson, as always, is that baseball is peculiar and defies sensible explanation.

Scott went after Martinez in the time-honored fashion, looking to change speeds and scramble his eye level by alternating fastballs up and away and sliders down and in. That led to a 3-1 count and a slider that was at the bottom of the zone — not a bad pitch by any means, but one a baseball’s height or so above where Scott wanted it, perhaps because his arm had been taxed and so was lacking a certain quantum of the critical pitching-related substance known as oomph. Martinez golfed the slider into the air, knew it was gone immediately, and happily trotted around the bases amid a post-homer light show.

Just like that the Mets had won, transmuting an annoying grind against a hateful opponent into a last-second reprieve and a triumph. Not one for Mets Classics — not by a long shot — but hey, it’s a shoo-in for Amazin’ Finishes.

by Greg Prince on 13 June 2024 11:13 am It’s gonna get away, you tell yourself when an early 2-0 lead becomes a 2-2 tie. When the lead is rebuilt to 5-2, you figure maybe — maybe — the scenario developing won’t be worst-case. Then instead of remaining 5-2, the lead shrinks to 5-4, and you can sense where this is going. Yet when it goes in the other direction a little, to 6-4, you’re willing to believe (a little) that your harshest instincts might be a little too quick to come to the fore. I mean, yeah, they’re probably gonna blow it, but only probably.

Then you get 8-4 and you think, “I’d feel better if it were 9-4. At 9-4, I’ll stop with the doomsaying. There’s nothing magical about a five-run lead as opposed to a four-run lead, but if we’re up five runs going to the ninth inning, given that we haven’t given up a run since the fifth inning, then perhaps this is an evening destined to be defined by good rather than ill fortune.”

And the lead becomes 10-4 and the ninth inning is at hand, and you remember what it’s like to watch the end of a Mets game in something resembling psychic comfort.

Ergo, Zeiles of Approval® all around for the eight Mets who recorded fourteen hits, especially Tyrone Taylor, who registered four of them. Taylor had been so quiet with the bat for so long, I’d kind of forgotten that he can hit. And let’s power-pack a few Zs of A for our three homer-hitters from Wednesday night: Harrison Bader in the two-hole with a two-run blow to get us off on the right foot in the first; Starling Marte, who went very deep in the fifth; and Francisco Lindor, who led off the eighth with his eleventh of the season.

If we’re tipping hats, lids doffed to Carlos Mendoza or whatever analytical algorithm is responsible for jostling the lineup just enough to make a difference versus the preternaturally pesky Marlins. There was Bader batting second, J.D. Martinez third, Pete Alonso cleaning up, beloved-in-Belgium Jeff McNeil in the ol’ Nido nine slot, and Brandon Nimmo sitting and watching for a night against lefty Braxton Garrett. Garrett was pretty hapless for his not quite five frames of rubber-toeing. That wasn’t necessarily a function of not benefiting from Nimmo’s icy hole in the order, but we’ll never know. Lineup shaken, offense stirred.

David Peterson didn’t go much longer than his mound opponent, but he survived a full five, and though he gave up four runs and didn’t qualify for the all-important quality start designation, every out matters, especially within a staff where too many of them are dumped on the bullpen. Mendoza could call on Dependable Dedniel Nuñez to begin the sixth fresh, and Nuñez could begin polishing his acceptance speech for when they hand him the Nobel Prize in Relief Pitching. Dedniel faced seven batters and presented each with a gold watch, retiring one after another on the spot. Alas, it’s more likely Nuñez was thinking of how to say “see you soon” for committing the twin sins of having pitched two-and-a-third and possessing a minor-league option on the eve of Edwin Diaz’s reactivation, but the man deserves his own Approval Zeile.

The path cleared by the only Dedniel we’ve ever known did not grow cluttered by the efforts of either Jake Diekman or Reed Garrett. The Marlin defense didn’t do its pitchers any substantial favors. And did we mention ten Met runs on fourteen Met hits?

Relax, you told yourself when it was over. We won, which doesn’t happen as often as the alternative does. We won with minimal stress other than the kind we inflict upon ourselves, which almost never happens. We drifted off into dreamland not thinking the worst of our team. I’m not sure if that’s happened in months.

by Jason Fry on 12 June 2024 7:40 am So the Mets came home fresh off a heady, game-saving final play by Luis Torrens … and looked pretty much like the Mets we increasingly have no interest in watching.

Francisco Alvarez returned from the IL, which seemed heartening, and Tylor Megill pitched well in the early innings against the Marlins, looking like a young hurler who’d kinda sorta maybe figured some things out. But then came a fifth-inning implosion in which Megill was shoved off a cliff by his defense. With runners on first and third and one out, Bryan De La Cruz hit a ball to the gap that went off Harrison Bader‘s glove as Brandon Nimmo strayed into Bader’s airspace, bringing in Tim Anderson with the tying run. (But not Jazz Chisholm Jr., because he is fundamentally unsound as a ballplayer in addition to being selfish.) No matter: After a flyout Mark Vientos didn’t take his time on a hard grounder to third from Jake Burger and made an errant throw to first, giving the Marlins the lead.

You can put asterisks on things if you like: The play Bader didn’t make was one of those “two center fielders” misplays that will happen until guys sort things out, and Vientos only made a throwing error because he first made a great stop on a hard smash. But that’s cold comfort: The Mets forced Megill to get two extra outs, it cost them the lead, and in another hour or so it had cost them the game, with an insurance run coming in following an Alvarez throwing error and the Met bats slumbering against whatever Marlin reliever was sent out to shush them.

Jet lag? The Phillies looked just fine in beating the Red Sox, though I suppose it’s true that Boston is closer to London than Queens is.

Nope, chalk it up to Met lag. You’ll know you’re a sufferer if the doctor finishes his examination, sighs, looks you in the eye and says, “Maybe you’re just not very good.”

by Greg Prince on 10 June 2024 2:42 pm Some wins you’ve got to have. You traverse an ocean and lose the first of two scheduled high-profile games, you’ve got to come home with the second contest in your carry-on. You catapult ahead from what the odds termed prohibitively behind, you’ve got to remain ahead until the end. You’ve got this reputation for inevitably finding a way to lose any game whose outcome is in doubt, you must discover a method that secures you victory. The Mets’ need to win on Sunday had nothing to do with the standings and transcended the concept of self-esteem; we sent our self-esteem to the cleaners weeks ago. There was nothing to gain, nothing to lose. But we had to win. Nobody who cares about the Mets was going to be well-served by a reminder that there goes this team they love Metsing it up again, despite all of us knowing that this team we love is capable at any moment of Metsing it up again. And again.

The ocean’s distance the Mets journeyed to absorb Saturday’s defeat and then attempt avoiding an encore result on Sunday was no small matter; baseball in London will grab your attention like no ten trips to Citizens Bank Park. The opponent was inconvenient for a team that usually stumbles into and out of ninth innings. The Phillies entered the series with the best record in the sport, even if they generally appear more talented than special. Although I’ve attempted to mute the echoes of 2022, I look at Philadelphia and I sense a bunch the Mets outclassed repeatedly just two years ago, with casts that at their core haven’t changed that much, yet here are the Phillies earning superteam status…and here are the Mets being the Mets most days. I saw on social media waves upon waves of Mets fans sending their greetings home from England because they took it upon themselves to represent the orange and blue five time zones east of Citi Field, then I see (and hear) little but scarlet and powder blue during the telecasts. We sent Mr. and Mrs. Met over there. I think the Phanatic devoured them.

Yeah, a win had to be had by the Mets on Sunday, and the Mets took it. Or accepted it with modest conviction when it was handed to them late. Maybe the Phillies decided they didn’t have room in their luggage for another one.

History was made as soon as Old Friend™ and designated home side twirler Taijuan Walker threw the game’s first pitch at 10:11 AM New York time. As outlined here, there aren’t many ticks on the 24-hour clock when the Mets haven’t been in action at least once. There are now 24 fewer minutes on that clock such can be said about. Thanks to extra innings in Tokyo in 2000, we watched/listened to/napped through the Mets on the job between 5:05 AM and 9:00 AM. Thanks to a lot of extra innings in Los Angeles in 1973, when games regularly started after 11 PM EDT, the Mets worked until nearly dawn: 4:47 AM back in New York. A Forbes Field doubleheader between the Mets and Pirates on July 4, 1969, commenced at 10:35 AM, beginning the Mets baseball day the earliest it ever had sans the Japan business. Now London on June 9, 2024, has usurped that distinction. For those keeping time, there are now only blocks of 18 minutes (4:47 AM to 5:05 AM) and 71 minutes (9:00 AM to 10:11 AM) that the Mets haven’t trod upon.

All this adjusting of Sunday morning routines seemed to be nonetheless steering us to a typically dreary loss, with Walker shutting down his opposition without sweat, and Jose Quintana providing less length than a yardstick. The corollary between starters going shallow and bullpens being overworked doesn’t require a trip across the Atlantic. We’ve already seen that formula play out from coast to coast in America, and boy is it played out. Quintana’s 3.2 IP Sunday on top of Sean Manaea’s 3.2 IP Saturday ensured too much relief and probably not enough relief.

The venue certainly didn’t help on Saturday. Odd sightlines from the vantage point of the outfielders. Bouncy turf at all points. The good news was those factors were in play for both sides, and on Sunday, you could see it hinder the Phillies some. You could also detect a quick hook performed on Walker, who was one out from getting through six scoreless, albeit with runners on first and second. Taijuan had thrown 79 pitches and given up no runs, one walk and two hits to that juncture. The walk and one of the hits had come in the sixth. Still, sometimes you beat back your albeits and leave your starter alone.

Rob Thomson opted to open his bullpen gate a little early. The Mets crashed through. Gregory Soto quickly whittled Walker’s 3-0 lead to 3-1 on a Brandon Nimmo double, then erased it entirely on J.D. Martinez’s two-run single. When it was 3-1, ESPN’s “win probability” graphic explained it was 88% probable the Phillies had this thing in the bag. Getting the game tied at three indicated they’d keep playing, regardless that mathematics suggested the Mets board their charter ASAP.

The Mets couldn’t push any more runs across whatever the British call the plate in the sixth, and they let a rally wither on the vine in the seventh. The overworked bullpen’s effectiveness — nothing surrendered between Quintana’s exit in the fourth and the close of the sixth — suffered a ding when David Dahl led off the bottom of the seventh with a home run off Dedniel Nuñez. Jake Diekman and Reed Garrett got the Mets through the rest of that inning no worse off than down, 4-3. If only you could ask relievers to do that every day and have them respond in kind.

A one-run deficit was still in place as the ninth unfolded. Jose Alvarado was on. Let me rephrase that. Jose Alvarado wasn’t on at all, but he did throw. He threw nine pitches to Tyrone Taylor who converted four of those into a leadoff walk. He threw two pitches to Jeff McNeil, the second of which became a Squirrely single that pushed Taylor to third. Mark Vientos bounced a ball to Alec Bohm at third, the bounce tricky enough on that turf to handcuff the barehanding third baseman and let Tyrone score the tying run. Then Alvarado walked the greatest catcher few among us knew two weeks ago, Luis Torrens, to load the bases. I don’t believe it was intentional, but it was all happening so fast, who could tell?

Let’s see: McNeil, mostly shunned these days, was at third; pinch-runner Jose Iglesias — who would pick up for Vientos at third a couple of innings after Mark did the same for Brett Baty (three third basemen in one day, with one making his club debut at the position, equaling a very Metsie thing) — at second; Torrens at first. How could you not love the Mets’ chances with the heart of their order coming up?

Because you know what the heart of this order can be like sometimes. Francisco Lindor struck out. Pete Alonso had the good sense to get hit and not get hurt, producing the go-ahead RBI. Brandon Nimmo followed by cleverly stepping aside as one of Alvarado’s 35 pitches went wild. Hey, 6-4, Mets! But then Nimmo struck out, Alvarado was replaced, and the Mets did no further damage.

They’d be granted the opportunity to do damage in the bottom of the ninth, with the caveat that the damage would be to themselves. Garrett, still in there, would take a turn at playing Met closer in the absence of rehabbing Edwin Diaz (whose lockdown properties were AWOL even when he was physically present). Reed allowed a leadoff single to Cristian Pache, elicited a foul pop from Kyle Schwarber (caught by All-Time Met Third Baseman No. 190 Iglesias) and hit J.T. Realmuto. Enough with Garrett, onto Drew Smith, forever the reliever I forget is on the roster. Bryce Harper recognized Drew and singled to right the first pitch he saw. Smith’s delivery was addressed with such authority that the Phillie runners already on first and second couldn’t advance more than one base, and Harper didn’t have time to make like Jamie Tartt and perform a soccer-style celebration. A modicum of Phillie exultation would have its chance five pitches later, when Smith completed a bases-loaded walk to Bohm.

It was now 6-5, Mets. The bases were still philled with Phillies. There was still only one out. Genuine power threat Nick Castellanos was still due up. Drew Smith was still Drew Smith. I neglected to check the Win Probability calculations, but counting on the Mets getting out of this jam rated as folly. But if you were feeling lucky, perhaps you wished to wager a quid or two on the Mets’ good fortune. It’s only some other country’s money, right?

The savvy gambler, however, noted that Luis Torrens lurked behind the plate. If we’ve learned anything of late, it’s never bet against Luis Torrens. Thus maybe we shouldn’t have been surprised that when Castellanos got the slightest piece of the last pitch Drew threw and it traveled only the slightest patch of dirt from home out toward the field, Luis a) pounced on the ball; b) turned around and step on the plate ahead of an onrushing Garrett Stubbs, pinch-running in Realmuto’s stead, for the inning’s second out; c) fired a dart to Alonso; d) nailed Castellanos for the inning’s third out, with agile Pete proving he’s in there as much for his glove as his bat by performing a neat pick of his own.

Maybe we shouldn’t have been surprised, but, oh, we were. We don’t see too many game-ending 2-2-3 double plays to preserve one-run leads with bases loaded. We don’t see the Mets execute rather than get executed that often, either.

The Mets held on, 6-5. The Mets held off the Phillies, 6-5. The Mets made watching baseball while we withstood both drowsiness and Michael Kay ultimately worthwhile, 6-5. The Mets weren’t that team that always finds a way to lose. That’s a departure from the routine welcome on any continent.

|

|