The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 31 December 2023 1:59 pm In one of those Faith and Fear traditions known only to me, I like to present a list as long as Eric Hillman’s left arm when my birthday falls on a Sunday. Since we’ve been doing FAFIF, my birthday has fallen on a Sunday twice, in 2006 and 2017. Today is the third time. I’m keeping my obscure tradition alive by presenting the first portion of a list I’ve been nurturing for several years.

These are MY FAVORITE MET SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT. Such a list itself wouldn’t be too long if it was just the list: 55 seasons that I’ve been watching the Mets, 55 lines on the list, done and dusted, go watch the ball drop. Of course a simple list with no expanding on the subject matter wouldn’t be any Sunday birthday fun for me. Being expansive about the Mets is what’s gotten me to 61 in as good a mood as I can be.

Creating a commentary-laden list that goes from least favorite to most favorite rides a somewhat predictable arc in my thinking. If I were to start with No. 55, the Met season I liked least from a personal perspective, I’d be very down on No. 55, and stay down for the first wave of the countdown because, you know, they’re my least favorites. “This went wrong, that went wrong, what a year, yeech.” It’s understandable. When you love a team the way we do, you really hate when things go badly for them and that’s gonna come through in any retelling.

I want to be in a good mood at the outset of 61. So here’s how I’ve decided to proceed. For the first dozen entries on the list of MY FAFVORITE MET SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT, I’m devoting myself to Something I Liked In Seasons I Didn’t. One distinct memory apiece from those dismal dozen when I can remember feeling pretty good in some way about and during a lousy Mets year. It was a bit of a challenge finding something nice to say about those Met circumstances that had little to recommend them when they were being lived, but that made taking it on more fun for me to put together. (This, you’ll note, is how I have fun.) I also tried my best to come up with material I haven’t used here before or at least haven’t delved into in quite the same manner. Apologies for any long lost redundancies. Apologies, too, for briefly transporting you to seasons you might wish remain lost. For me, “least favorite” implies some strain of favoring, however slight it might be.

Bob Murphy continually reminded us baseball is a game of redeeming features. Every season has those. That’s what this segment of this countdown is all about.

I’m limiting myself today to one glass-half-full anecdote for twelve mostly empty seasons. The seasons that are more favored will be counted down in a different style in upcoming posts. That’s the plan, anyway. I’m a tad pokey about following through on these multipart series ideas of mine, but we’re getting the least-favorite seasons out of the way right here, right now. It can’t help but get sunnier in the new year.

***55. 1977

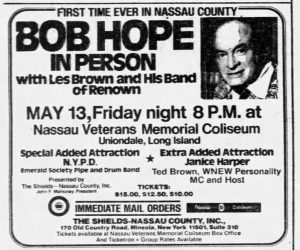

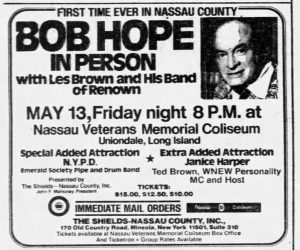

Bolstered by the magic of twi-night doubleheaders, the Mets played 29 games on Fridays in the year they a) traded Tom Seaver on June 15; b) determined the National League East cellar would make a nice long-term rental; and c) left few positive impressions in their wake. They lost 21 of those particular dates, including nine in a row spanning May 20 to July 1, indicating maybe Friday wasn’t destined to be their lucky day of the week whether they held onto The Franchise or not. Yet my clearest memory of any Friday game from 1977 comes from a win: Friday the 13th of May. My friend’s father had come into a boatload of tickets for a Bob Hope show at the Nassau Coliseum that night and was quite generous with his windfall, inviting my parents and me to join a rather large party to watch the ageless comedian ply his craft. I remember one Hope joke: President Carter has reached out to fill the White House with advisers from the north, south, east and west…of Georgia. I also remember the lot of us going out for ice cream at the Apollo Diner in East Meadow afterwards. So I didn’t see the game, but I recall getting home in time for Kiner’s Korner, from which I learned Dave Kingman had homered and the Mets had topped the Dodgers at Shea, 3-0. Sky King had been in a mood all season — he’d be traded the same night as Seaver — but here he was, performing his Dave Kingman core competency, hitting a “long, towering two-run homer,” per Steve Jacobson’s description in Newsday, two batters after Lenny Randle sent his first Met dinger over the 396 mark in left-center. “An accident,” the good-natured newly acquired infielder called his shot. “My quota is about one a year.” Randle made some nice plays at second, as did contingency third baseman Jerry Grote at his temporary position. Jon Matlack threw a seven-hit shutout to quell the Dodgers, who entered the evening at 24-6. Conversely, the Mets had won once in the past dozen days; they hadn’t even led in a game since the previous Sunday. Before Jon beat L.A., the Mets were 10-19. A few days earlier, the lefty revealed to Joe Durso of the Times that he was “fed up” with how the Mets were going about their business on and off the field. Kingman’s reaction to his eighth homer of the year (and second-to-last before he became a San Diego Padre)? “I don’t care anymore. I just play my game.” The Mets hadn’t exactly turned their frown upside down, yet this game got played to a pleasing decision for a change. Ralph had bona fide home team highlights to share and the 1977 Mets provided me with a wisp of optimism that these guys might pull themselves together rather than continue to completely fall apart. They didn’t, but for a minute I could be convinced otherwise. Thanks for the memory?

54. 2003

“I hated the Dodgers with that love that only hatred can understand,” is how Stephen Jay Gould summarized being a Giants fan in 1951 on Ken Burns’s Baseball in 1994. I’ve mulled that sentence over for nearly thirty years, and I still don’t know what it means, but I’ve always liked the way it sounded. Perhaps that also fits how I viewed the Mets in 2003. They replaced Bobby Valentine with Art Howe. They let my favorite player, Edgardo Alfonzo, walk. They dumped my wife’s favorite player, Rey Ordoñez. They imported T#m Gl@v!ne from the Braves and Mike Stanton from the Yankees. They created the first Mets team that I pretty much hated in advance, albeit with a hatred informed by love. Or something like that. It was as unlovable an edition as I had encountered in all my years of being a Mets fan, but I was still a Mets fan, regardless that I couldn’t stand these Mets. I still cheered for various Mets. Sometimes they were wearing other uniforms. On June 6, the Seattle Mariners came to town, which meant John Olerud was coming to town, which meant I would be at Shea Stadium to let John Olerud how much I missed him. I was almost as irritated with the Mets letting Oly go in December 1999 as I was with their making the same decision vis-à-vis Fonzie three winters later, but those Mets had too much going for them to seriously test my ardor. In 2003, I’d already rooted for an ex-Met over a current Met once, when Jesse Orosco filled in as closer for the Padres on May 9 and his chance to notch a save at Shea — something he’d done most memorably one October night versus the Red Sox — meant he’d have to retire Roberto Alomar. I already didn’t like Alomar. I was watching from home. It was an easy call. C’mon, Jesse. Orosco struck out Alomar with two on and two out. I clapped for the pitcher. The Mets lost? So what? 1986 took a curtain call, something 2003 would never be asked to do. Four weeks later, though, my fondness for Olerud and all he’d meant from ’97 through ’99, couldn’t quite break through another ninth inning. This time I was at the game. It didn’t matter that I loved Oly and I was past the end of my rope with Armando Benitez. Armando was protecting a one-run lead with two out and a runner on first. He was as capable of blowing it as he was of saving it. A Met win wasn’t going to mean anything in the scheme of 2003. John worked a three-two count. Of course he did. He was beautiful that way. Benitez was agita personified. The Mets deserved to have John Olerud, in his first trip back to Flushing since he advanced unmolested from second to third once the Grand Slam Single departed the park, remind them of who they felt fine about replacing with Todd Zeile. Yet, I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t root for one of my favorite Mets to stick a pin in the world’s largest Armando Benitez voodoo doll, not as long as he was a Seattle Mariner in my midst. Benitez struck out Olerud. I approved. It was the approval only disdain can understand. Or something like that.

53. 2002

My dismay for the 2002 Mets wasn’t set in stone ahead of time as it would be in 2003, but it was inevitable. Bad mix of personalities, bad results the rule by May, a total disaster by September. Still, on September 21, a Saturday night at Shea — and I’m not a huge fan of going to Saturday night games to begin with — I’d forgotten how disgusted I had become with the 2002 Mets over the previous five-and-a-half months once the Mets forced extra innings versus the Expos. Did I say “forced”? More like the Mets walked through the door to the tenth Montreal held open for them in the bottom of the ninth. Sure, the Mets had first and third, but with two out, Brady Clark grounded to two-time Gold Glove winner Andres Galarraga at first. All Galarraga had to do was throw accurately to second to end the game, 3-2, in favor of Les ’Spos, but Andres’s last Gold Glove came in 1990. His errant fling into left field furnished the Mets with the tying run. Come the eleventh (after Armando Benitez held up his end of the bargain with two scoreless frames), Joe McEwing absorbed a hit-by-pitch with one out, Roger Cedeño drew a base-on-balls with two out, and Esix Snead, the kind of player for whom garishly expanded rosters were conceived, belted a three-run homer to win it. Esix had been on the club since September 3, primarily to pinch-run. He entered this game as a pinch-runner in the eighth and was picked off. In the tenth, he delivered a leadoff single for his first hit in the major leagues, but was stranded at second. Snead left no doubt in the eleventh. “It’s pretty exhilarating,” the rookie said, expressing a sentiment nobody around the Mets had any cause to otherwise articulate of late. A week remained in the season. The Mets were going nowhere and they were doing in front of almost nobody. But as soon as Snead went deep to right, those of us who’d stuck around to the non-bitter end had detoured into a September to Remember. I was jumping around like House of Pain was back on the charts, high-fiving my pal Joe over and over and truly believing there was no better place to be on a Saturday night than Shea Stadium at the tail end of a last-place campaign. Hot damn, I was at The Esix Snead Game.

52. 1992

They weren’t yet dubbed The Worst Team Money Could Buy, but had you told the bulk of Mets fans by June 1992 that a book bearing that title would be out the following April and it would be about this team that was repeatedly frustrating us, we wouldn’t have blinked. Ah, but before it was abundantly clear what a debacle we were bearing witness to, there was Daryl Boston’s shirt and the ball that landed inside it. It was the sunny afternoon of April 23, a Thursday matinee at Shea. I wasn’t there, but I was close enough, sitting at my desk in Great Neck with the radio on, enjoying one of those day games that feels as if it’s never gonna end, now and then sharing updates with co-workers who cared and co-workers who didn’t. Bret Saberhagen pitched nine scoreless innings. Alas, so did a combination of two Cardinal pitchers, which meant extras were at hand. The eleventh was to be our downfall, if you assumed two singles and a walk to the opposing lineup with nobody out augured the worst. Assume nothing — Dave Magadan made two swell plays at third base and St. Louis couldn’t score. Still zip-zip, all the way to the bottom of the thirteenth, when the Mets loaded the bases, bringing up Boston. Redbirds reliever Juan Agosto managed to land a one-two pitch inside the loose-fitting jersey of the batter. It went onto your scorecard as HBP and RBI. Daryl plucked the ball out of his clothes and handed it to the umpire. Mets 1 Cardinals 0 in a shade under four workday hours. Some kind of omen for the season ahead, the listener at his desk thought before starting to spread the news throughout the office. It was no kind of omen, actually, but it was April, and the team for which he rooted seemed to be worth whatever they were being paid.

51. 1993

If ever a team inspired a fan to agree with McDonald’s that we deserved a break today, it was the 1993 Mets, whose rousing 12-2 victory over the Reds in Cincinnati on Wednesday August 18 raised their seventh-place record to 42-78, a mere nine games behind sixth-place Florida, a team that hadn’t existed before the current season. The Mets had a travel day Thursday, then a scheduled off day Friday before resuming their schedule in Colorado on Saturday evening with a twi-nighter against the NL’s other expansion team. No baseball planned for Friday was odd but explicable. The Denver Broncos had a preseason game at Mile High Stadium, so the Rockies had to work around the venue’s primary tenant’s priorities while Coors Field was under construction. Being left alone by the 1993 Mets sounded heavenly. I filled my Thursday evening void by tuning into the staticky Phillies’ broadcast on 1210 AM (Lenny Dykstra’s bunch had a certain appeal), and I was musing that if I absolutely had to, I guess I could go on as a baseball fan without the Mets if I had a strong enough antenna. Then Friday came, and the godawful Mets remained in absentia, and so help me, I missed them. Not that team and its toxicity, just the day-to-day Metsiness of what a season is supposed to give us, even in the moldy basement of a season like the one in progress. The 1993 Mets returned to action Saturday and lost twice to this other team that hadn’t existed before the current season. Everything was still lousy. Everything was all right again.

50. 1979

On one hand, there was a final dress rehearsal. The Long Beach High School production of Li’l Abner would have its world premiere on Friday night, April 6, featuring for one scene yours truly in the key (from an expository sense) role of Senator Jack S. Phogbound. But the Thursday afternoon before, directly following eighth and final period, we would run it through one time as if we were going on stage in front of an actual audience…which we were, courtesy of a group of seniors — actuarial rather than high school — bused in from a local nursing home. The show went great, and our cast was brimming with confidence ahead of Opening Night. The only fly in the ointment was the final dress rehearsal conflicted with the curtain rising on the 1979 Mets season in Chicago. Alas, in order to deliver my briefest of solos (of all the very/ordinary/most unloved/unnecessary/places on this earth…), I had to miss the first pitch from Wrigley and the initial innings of the new year as well. Thankfully, I was home in time for the ninth. The Mets had a 10-3 lead, built largely on Richie Hebner’s four-hit, four-RBI debut. They always won on Opening Day, right? The Cubs, however, stirred and made it 10-6 with a runner on when Joe Torre went to his 21-year-old rookie out of the pen, Jesse Orosco, the player to be named later from the Jerry Koosman trade. Our callow southpaw, wearing No. 61 without a name on his back (all his teammates were properly identified), would have to face one of the most dependably dangerous lefty swingers in the league: Bill Buckner, a .323 hitter the year before. This was a game that couldn’t get away, and it didn’t. Orosco induced Buckner to fly to right, and the Mets were perfect in 1979. As, I daresay, was Li’l Abner on Friday night. Saturday night’s show, however, lacked that certain something, but that was OK, I guess, considering it was our Closing Night. Besides, the Mets won Saturday afternoon. We were 2-0. Hebner was batting .556. I never performed in another musical again. The 1979 Mets, about to lose 99 games, might have considered taking a cue from the ol’ Senator here.

49. 1982

I was a car washin’ college man on a Sunday afternoon, making like Judge Reinhold as Brad Hamilton in Fast Times at Ridgemont High in the driveway of our house a couple of weeks before I was due back on campus. Determined to take care of my burnt orange 1981 Corolla (or, more likely, nagged into it by my mother), I had the hose, I had the bucket, I even had a fresh tin of Turtle Wax, a product I thought existed only as a consolation prize on Let’s Make a Deal. Whereas Brad scrubbed his “Cruising Vessel” to the strains of “Raised on the Radio” by a group called Ravyns, I went about cleaning my baby with WMCA on in the background. I was raised on the radio for Mets games if Channel 9 wasn’t televising them. Bob Murphy was exclusive to radio as of 1982, joined by newcomer Steve LaMar. In the first game of the doubleheader of August 15, Murph and his freshman partner kept me effervescent as I rinsed the bubbly water off my “Orange Flame”. The Mets took a lead in the fourth. Ed Lynch pitched serviceably for seven. When Jesse Orosco struggled in the ninth, George Bamberger called on Pat Zachry with the bases loaded. Pat worked out of Jesse’s jam and notched his only Met save. The Mets had started the season in promising fashion, rising to six games above .500 on Memorial Day. They proceeded to fall out of contention with a thud, but they did just beat the almost as lousy as them Cubs, and maybe, despite a 50-65 record, they could recover some momentum for the stretch drive. At the very least, maybe they could sweep this twinbill and make a move on respectability. But they lost the nightcap, then all nine games of their near-West road trip through Cincinnati, Atlanta and Houston, mounting a losing streak that would remain unabated as I made my own stretch drive from Long Island to Tampa to begin my sophomore year at the University of South Florida. After three days of classes, the Mets’ season victory total stayed stuck on 50. Their defeat total was up to 80. They executed a fifteen-game skid that washed away the residual vibes of not just 1982’s flashy start, but all that “Magic” stuff from ’80 and ’81. But, man, didn’t Bob Murphy sound great while I washed my car?

48. 2009

What could go wrong did go wrong Metwise in the first year of Citi Field, a place I found myself resenting more with every visit. I was still mourning the passing of beloved Shea Stadium, and the team inhabiting its successor facility wasn’t distracting me with great play. I’ll say this for the new joint: it had superb food and was brimming with retail. That may not have jibed with purist instincts (“it’s more like a mall,” was a common refrain), but inside the sprawling team store within the Jackie Robinson Rotunda, there was a cap that caught my eye. It was a modern take on the late 1970s “Superstripe” model. The Superstripe caps were regularly advertised in Baseball Digest and other indispensable periodicals of the day. They were produced for all teams in all major sports, including the Mets, and I had a Mets version. There was no mistaking what team it represented as their name was spelled out amid the striping. A white mesh back, adjustable sizing, not particularly well made, but I appreciated that it was made at all, seeing as how the print ads never spotlighted the Mets. Three decades later, the Sunday before the All-Star break, the cap beckoned to me as I browsed pregame. I tried to ignore its siren song of nostalgia for my youth, as it was kind of pricey (what wasn’t at Citi Field in 2009?), but I couldn’t get it out of my mind. Come the seventh-inning stretch, I slipped away from Promenade, tromped down those endless flights of stairs that were no aesthetic match for Shea’s ramps and made my purchase. The 2009 version of the Superstripe cap was a quality item. Almost too well made, but it was objectively better than my long-gone 1978 cap. The back was blue. The bill was orange. It was fitted. The “NY” in the middle of “NEW YORK” and “METS” was prominent enough to be discerned coming down the block. It became my game cap of record for the next decade, the one I took the most relish in grabbing as I headed out to catch my westbound train. I still wear it to Citi Field once or twice a year. I don’t resent the not so new ballpark any longer. I got my favorite cap there.

47. 2023

The most recent spate of Met misery didn’t prevent me from finding my way to Flushing on thirteen separate occasions, sometimes as something approximating working press, sometimes on a solo mission of the soul, but mostly to meet up with a really good friend. As these meetups begat more meetups, despite the Mets having given up the ghost of competing for a playoff berth, it occurred to me that this person I was having a good time sitting next to would also make a splendid lunch or dinner companion, and we could have very well done that today or tonight. Yet I knew this — going to see the Mets, even the 2023 Mets — was better. I wasn’t watching the game as closely as I would have had I been focused on it at home, but how closely did this team need to be watched? And me and whoever, we weren’t face to face much in the course of the couple of hours we were together, because we were looking at the Mets rather than each other, but we could hear each other fine, at least when the Citi Field A/V squad wasn’t urging everybody to GET LOUD. “A hot dog just doesn’t taste right without a ballgame in front of it,” Charlie Brown once declared. I’d add friendship tastes even better with a ballgame in front of it.

46. 2017

The Mets won the pennant in 2015, returned to the playoffs in 2016 and got off to a roaring start in 2017. All they had to do was keep roaring, and everything was going to be fantastic. The last legitimate roar came from the bat of Travis d’Arnaud on April 13, when our catcher conked Adam Conley with a sixteenth-inning leadoff homer at Marlins Park to give the Mets a 9-8 lead, an edge the skyward-pointer himself, Hansel Robles, preserved in the bottom of the frame. It was a long night (5:38), one that I snoozed through a bit of, but I woke up in time to see it won. The Mets, on a five-game winning streak, were 7-3. The bad Marlin juju we bake into our expectations hadn’t derailed them. Marcell Ozuna’s grand slam off Robert Gsellman way back in the first inning hadn’t buried them. They came right back with four runs in the top of the second, two in the top of third and one more in the top of the fifth. Yoenis Cespedes hit two out of that Miami monstrosity. Gsellman and Josh Edgin didn’t maintain the lead, but Michael Conforto got it back for us in the eighth. Then eight more innings, or as many as were required to get to 9-8 on the scoreboard and 7-3 in the standings. This was both sincerely appreciated and reasonably anticipated. The Mets of 2015 and 2016 and now 2017 were the payoff for all those dismal years of muddling in place. I truly believed we were ensconced in a legitimate era of Met success. The Mets lost ten of their next eleven, twenty of their next twenty-nine and finished 70-92. They’ve swerved in and out of eras every few months since that night in April of 2017. That’s the era I wish had kept going. It felt like a pretty good place to put down roots.

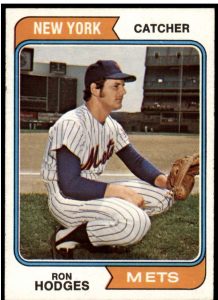

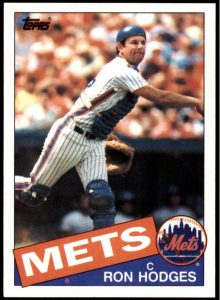

45. 1974

The kid’s name was Hal. His last name began with a P. I can’t quite remember what it was. It doesn’t matter. To me, he was Hal with the wristbands. This was during day camp in Oceanside, in July of a year when the Mets would definitively not repeat their success of 1973, and on the night before, Hal had gone to the Mets game. He mentioned it casually. Or maybe he announced his presence with authority. Whatever he didn’t say was there on his wrists. He was wearing Mets wristbands, acquired at Shea Stadium the night before, when he was at the game. I wasn’t so much envious of Hal with the wristbands — certainly not for the wristbands themselves — but I admired like hell his off-hours activity. As of that July day in 1974, I had been to two Mets games, once via the day camp I attended the previous summer, once with my older sister and a friend of hers a few Saturday afternoons prior. They were extremely special occasions that had to be carefully planned, either by enrolling at a camp or perusing the schedule and agreeing on a date. Yet here was Hal and his wristbands casually confirming he went to see the Mets on a weeknight. I’d heard of such things, the idea that somebody would decide to go to a game and just go. I don’t know how the decision was executed in Hal’s household, yet as far as I could tell, it was no big deal, wristbands or no wristbands. “I went to the game last night” was something I now wanted to be able to say like it was something I actually did. Eventually I would. I wouldn’t walk around the next day with any goddamn wristbands on. C’mon, Hal. Act like you’ve been there before.

44. 2020

In September, when I hadn’t been on a train except for the briefest of local hops since February, I considered boarding the LIRR and taking it to Woodside just like I would in any September, then switching for the 7 to Mets-Willets Point, also a familiar maneuver. I was going to get off the elevated line, walk downstairs, find a bench or lean against a post and turn my radio on to listen to the Mets play the Rays a few hundred feet away. I couldn’t go into Citi Field, as no fan could go into Citi Field while a pandemic was in progress and no vaccine for it was available. I understood I couldn’t go inside a ballpark. I watched the action on TV once it started up in late July, the very essence of better than nothing. Nothing was the attendance at every game, unless you counted those eerie corrugated cutouts, which I didn’t. Still, on September 23, I debated with myself the necessity to get as close as I could to the final home game of the regular season because I always went to the final home game of the regular season. I had an active 25-year Closing Day streak, dating from 1995 forward. It would necessarily hit pause in 2020, but shouldn’t I do something to spiritually keep it going? I ended up not acting on the impulse, safety being the better part of whatever while COVID lurked behind every corner. I picked up the Closing Day streak the next season and have kept it going ever since; it comes with a semi-colon now (1995-2019; 2021-Present). Once in a while, I picture myself taking that 2020 trip for the streak’s sake. It was a silly notion, but not inconceivable to a fan like me.

The final regularly scheduled edition of National League Town is available for your listening pleasure on Spotify and other podcast platforms. Pop it on, as the people who say things like that like to say.

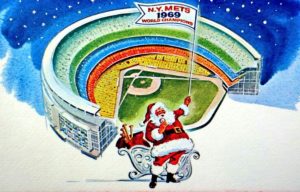

by Greg Prince on 24 December 2023 9:57 am I don’t observe Christmas in the ecclesiastical sense, but I’ve watched a lot of Christmas episodes of sitcoms, both live-action and animated, so I understand assisting Santa Claus when asked is necessarily a good thing. Every year around this time, I hear that a reindeer with a nose visible in fog went down in history for lending a hand (or hoof). Thus, when Santa got in touch with me about a week ago and asked me to help right a few historical Met wrongs, of course I listened.

Santa let me know he was going over some old correspondence, and mixed into the letters he’d received from children far and wide was a folder filled with printouts of National League Rookie of the Year balloting results from 1962 to the present. The man in the red suit told me he was astounded at some of the names he didn’t see on those lists, specifically the Met rookies who never got any attention when it came time for the Baseball Writers Association of America to honor a given year’s freshmen. It seems Santa watches a lot of baseball during his summer vacations and figured more Mets would have received more support for ROY awards than they have.

Mind you, Santa isn’t endorsing greed. He’s quite aware that six Mets — Tom Seaver, Jon Matlack, Darryl Strawberry, Dwight Gooden, Jacob deGrom and Pete Alonso — have won the Rookie of the Year award, and four others — Ron Hunt, Jerry Koosman, Steve Henderson and Kodai Senga— finished a respectable second. He knows, too, that the balloting has been dotted by Met comers from Cleon Jones in 1966 to Andrés Giménez in 2020 receiving at least token support, which itself represents a nice little reward for a player who’s just made the major league scene. Santa is also hip to the historical reality that the BBWAA has conducted ranked voting for ROY only since 1980. Before that, writers would fill in just one name as their Rookie of the Year choice, reducing the opportunity to dispense a “nice first season there, young feller” consolation point or two to nearly nil.

Yet Santa is all about who’s been nice; naughty, too, but he’s trying to maintain an upbeat attitude in these turbulent times. He hates to think kids who tried their best and did rather well didn’t get a little official recognition for their efforts. That’s when Santa reached out to me via Zoom.

Blogger, with your Stathead

Subscription up to date

Won’t you assign some down-ballot points

Before it’s too late?

“Seriously,” Santa continued, “I’d like to get them distributed by Christmas Eve to ensure that they’ll be hung by the chimney with care. Surely you’ve heard that old chestnut.”

My December 24 looked clear, so I told him OK. Santa was asking simply that I arrange for some stocking stuffers…a point here, a point there for the Met rookies of yore who surely deserved to be mentioned on at least one ballot. I asked if I needed to do deep dives to discern who is most deserving; whether I should relitigate the rookie campaigns of multiple National Leaguers who perhaps shouldn’t have gotten votes Mets rookies could have gotten; might I have to take into account how careers unfolded with decades of hindsight at my disposal; and if this exercise would benefit from calibration of candidacies vis-à-vis other forms of rookie recognition from the likes of Topps, Baseball Digest or the Sporting News, which in their day were kind of a big deal.

“Use your judgment,” Santa replied. “Be as statistical or as anecdotal as you like. I trust you to use your head and your heart and arrive at reasonable conclusions.” Bolstered by the confidence Santa Claus expressed, I was ready to take on the task with so much holiday cheer that you could have spread the excess across the tray of Christmas cookies baked in the getting-to-know-you scene of whichever movie the Hallmark Channel is airing at this very moment. Still, as St. Nick was about to log off Zoom and get back to loading his sleigh to beat the holiday travel rush, I had to throw one more question at him.

“Santa? How come you didn’t deliver Yoshinobu Yamamoto to Flushing? You would have made a whole lot of kids from 1 to 92 happy if you had.”

The connection went dead at that point for some reason. Oh well. I can’t worry about that now. I have to stuff some stockings. A dozen is a good figure, I figure. I seem to recall something about twelve days of this particular holiday, and I can’t imagine too many fireplaces are grand enough to hang more stockings than that.

But into which erstwhile Met rookies’ stockings should I be stuffing the ballot socks, so to speak? To use the modern noun-as-verb parlance, I’m going to “gift” a point to the dozen Mets listed below — six pitchers, six position players. I’m not suggesting they were robbed of the Rookie of the Year award. Rather, I’m giving them the simple shoutout they deserved all along.

Oh, look! Twelve stockings belonging to first-year Mets have indeed been hung by the chimney with care! It’s a Christmas miracle!

GARY GENTRY, 1969

Did I mention Santa was particularly mystified that a pitcher for the National League East champions who was trusted by Gil Hodges to start 35 times — including the division-clincher in which the righty shut out the Cardinals — was completely overlooked by the 24 writers who voted for Rookie of the Year? And that from a distance of 54 years, the NL rookie class that did attract votes doesn’t seem to have been all that impressive in their neophyte stage? How do 13 wins for the 1969 Mets not make a dent? These elections have nothing to do with postseason performance, but the Mets won both of Gentry’s starts in the playoffs and World Series.

A 1969 National League Rookie of the Year runner-up vote has been stuffed in Gary’s stocking.

FRANCISCO ALVAREZ, 2023

We’re shooting straight to the present for this present. Francisco Alvarez belted 25 home runs and began mastering his craft behind the plate almost immediately after he was called up ahead of schedule. The pitchers, including the crusty veterans, praised him to the high heavens. Word even reached the North Pole, where Santa has been appreciating the hard offseason work Alvarez has been putting in to get even better as a sophomore.

A 2023 National League Rookie of the Year runner-up vote has been stuffed in Francisco’s stocking.

DAVID WRIGHT, 2004

The 21-year-old Virginian wasn’t summoned to Queens until late July. You know who else wasn’t promoted to the majors until late July? A first baseman named Willie McCovey, in 1959. McCovey whacked 13 homers and drove in 38 runs in 219 plate appearances and was awarded Rookie of the Year unanimously. Operating from the opposite corner of the infield early in the next century, David’s power numbers were as eye-popping as Stretch’s: 14 home runs and 40 ribbies in fewer than 300 PAs. Wright gave every indication a beautiful career was off and running from the get-go, and every moment from 2005 confirmed our initial faith.

A 2004 National League Rookie of the Year runner-up vote has been stuffed in David’s stocking.

TSUYOSHI SHINJO, 2001

A cult hero with credentials! Two walkoff hits! Sacrificed one of his quads to beat out a double play grounder and set up Mike Piazza for one of the longest blasts in latter-day Shea history on a Sunday night in the Subway Series! Inspired the Daily News to splash SHINJOY across the back page! Took the orange in orange and blue to heart by modeling it in his hair! You can’t ignore a major league first year like this one.

A 2001 National League Rookie of the Year runner-up vote has been stuffed in Tsuyoshi’s stocking.

DILLON GEE, 2011

Overlooked in his time, this kid knew how to get outs as soon as he came up to the bigs in September of 2010, breaking in with five no-hit innings at Washington. In his first full year, for a team that was lighting nobody’s world on fire, Gee won 13 games, or as many Gentry notched pitching for a much more competitive Met outfit. Proved a stopper at Atlanta in April when he halted the club’s seven-game losing streak. Proved enduring when, in his final September start, he foiled the powerhouse Phillies. The Braves missed the playoffs by one game, while 102-win Philadelphia, shorn of its inevitability, fell in the first round back when that sort of thing rarely happened to an odds-on pennant favorite

A 2011 National League Rookie of the Year runner-up vote has been stuffed in Dillon’s stocking.

MARK BOMBACK, 1980

The surprise rock of a rotation that was an essential part of making Mets fans believe in Magic for a few months. Peaked at 9-3 in August, before the whole team kind of went poof. On a staff ostensibly led by veterans Swan, Zachry and Burris, it was Bomback who led all pitchers in victories, the only Met hurler to reach double-digits in that then critical department.

A 1980 National League Rookie of the Year runner-up vote has been stuffed in Mark’s stocking.

RICK AGUILERA, 1985

An underappreciated component of the most compelling wire-to-wire pennant drive in franchise history. Aguilera came up minus fanfare in the middle of June and was soon constituting a fifth of a youthful rotation headed by Gooden, Darling and Fernandez. Had a knack for shining amid potential Metsian messes. Who won the night after the Mets were steamrolled, 26-7, at the Vet? Who chose the night after the 19-inning game at Fulton County to throw his first career complete game? Whose starting pitching set the stage for five Met victories in September, when every win was crucial?

A 1980 National League Rookie of the Year runner-up vote has been stuffed in Rick’s stocking.

RICO BROGNA, 1994

As long as they were giving out what amounted to short-season awards in strike-curtailed 1994, BBWAA members should have looked a lot more closely at the first baseman who rose to the majors in June and started lighting the NL on fire: a .351 average highlighted by seven long balls. If writers were hip to OPS+ nearly thirty years ago, they would have been gobsmacked by the kid from Connecticut posting a 158 in that category. It’s not Brogna’s fault baseball ended on August 11.

A 1994 National League Rookie of the Year runner-up vote has been stuffed in Rico’s stocking.

RON SWOBODA, 1965

Dynamite power-hitting first half, featuring fifteen dingers. He tailed off in the second half, but c’mon. This is 1965, the Mets’ fourth year of heretofore futile existence, and Swoboda is showing the league the Mets can produce somebody productive. This Youth of America talk may really be something more than Casey Stengel prattling on.

A 1965 National League Rookie of the Year runner-up vote has been stuffed in Ron’s stocking.

DOUG SISK, 1983

Anybody here want to follow Tom Seaver to the mound on the afternoon Tom Seaver has executed the most emotional homecoming in Shea Stadium history? You there, the reliever we called up for an audition last September — yeah, you. Here, take the ball, maintain Tom’s shutout and keep a lineup crammed with likely future Hall of Famers off the board while we try to make like Hanover and manufacture a run or two. Nice way to start your first full season if you can get it, and Sisk got it, picking up the win over the Pete Rose/Joe Morgan/Tony Perez/Mike Schmidt Phillies in relief of Seaver on Opening Day and going on to form a meaningful third of one of the franchise’s most formidable bullpen trios ever. That was Sisk succeeding the traded Neil Allen as the Mets’ main righty in relief, nailing down 11 saves and operating in sync with frontline closer Jesse Orosco and dependable lefty Carlos Diaz as they protected leads and held forts all season long.

A 1983 National League Rookie of the Year runner-up vote has been stuffed in Doug’s stocking.

SETH LUGO, 2016

Lugo was snuck into the bullpen at the outset of July and mopped up intermittently as the Mets slipped and slid on the periphery of contention. With almost every starting pitcher injured and not a lot of alternatives at hand, Terry Collins inserted the righty whose spin rate was off the charts into the rotation in late August, and by some Amazin’ coincidence, the Mets rocketed into the Wild Card race, eventually taking command of it. From August 25 through September 28, Lugo made seven starts, and the Mets won each and every one of those games. The starter’s record in that span: 5-0 with a 2.45 ERA, all compiled amid genuine pennant chase pressure.

A 2016 National League Rookie of the Year runner-up vote has been stuffed in Seth’s stocking.

BENNY AGBAYANI, 1999

In his first twenty-seven games as a 1999 Met, between May 11 and June 13, Agbayani blasted ten homers and pretty much created the OPS metric. The unheralded outfielder’s on-base average plus slugging percentage measured 1.338 in that first golden month-plus. The Hawaiian Punch graphic that began to grace the Shea scoreboard was quite literal. As the 1999 Mets were morphing into the 1999 Mets — dripping with drama, crammed with charisma and shining with stars — there was a period where you couldn’t help but think of them as Benny and the Mets. And even when the youngster cooled off some, he was still an important part of all that was going on, right through Game Six of the NLCS, when he scored the final Mets run of the millennium.

A 1999 National League Rookie of the Year runner-up vote has been stuffed in Benny’s stocking.

Two more votes are cast here as well: 1) for a wider fireplace mantel that would allow for the hanging of some more stockings into which retroactive Rookie of the Year votes would be stuffed on behalf of other worthy Met kids who took a bit of our breath away right away; 2) and for you, dear reader, to experience true (if Yamamotoless) joy the rest of this holiday season, the rest of this offseason, and all the seasons ahead.

by Greg Prince on 21 December 2023 4:09 pm Although baseball has already conducted its winter meetings, winter insists on meeting the rest of us this evening at 10:47 PM Eastern Standard Time. We wish a scintillating solstice to all, yet we’ve got a bigger milestone to mark before the month is out.

That’s right: the Baseball Equinox is nigh! At 3:26 AM EST on Saturday, December 30, 2023, we will sit exactly between the final out of the 2023 Mets season and the scheduled first pitch of the 2024 Mets season. That’s 89 days, 9 hours and 44 minutes after Phillies shortstop Edmundo Sosa caught Pete Alonso’s two-out, ninth-inning pop fly to shallow left last October 1, and 89 days, 9 hours and 44 minutes before you’d figure Kodai Senga throws his first ghost fork to whatever leadoff hitter David Stearns hasn’t liberated from the Brewers by this March 28. Incumbent ace Senga is a best guess for Opening Day starter at Citi Field, but it’s only a guess. So much can happen and occasionally does. For example, you wouldn’t have hazarded a pre-Equinox projection that Tylor Megill rather than Jacob deGrom or Max Scherzer was going to be our Opening Night pitcher in Washington in 2022, nor that the Opener three years running from 2020 through 2022 would be postponed, once from a pandemic, once because too many of the Mets’ opponents tested positive for COVID, and once when a lockout took its sweet time unlocking itself.

If life in this decade has taught us anything, it’s that presumption can occupy too much roster space of the mind. If the Mets in this decade have taught us anything, it’s to presume nothing. The calculation of the Baseball Equinox is offered as a public service to make the coming of Spring a little more visible a little sooner, but whatever might happen on the far side of the BE is not to be written in indelible ink until it actually happens.

We also happen to have completed 40% of this decade’s baseball seasons, which isn’t any kind of a milestone, exactly, but it’s got me thinking about the Mets and the 2020s. Decades don’t usually get anybody’s attention unless one is winding down and the next one is looming. But why wait for the last gasps of 2029 to get a handle on this one?

From a Mets perspective, it could use a boost.

The four seasons of the 2020s to date have had one thing in common: none of them has felt great in the months that followed them. Three encompassed losing records; two saw first place slip away; the lone campaign that seemed to be rolling merrily along faded in frustration. We entered the 2020s with lofty expectations, failed to meet them, reset our sights even higher a couple of times, and fell to earth successively harder

Even if we allow that decades are arbitrary chronological constructs, this one has been dismal four Met years in…which is pretty much par for the Met course in terms of how our decades commence. Let’s give the first four Met years of the 1960s and their relentless 100+ losses per annum a break, given that for Met purposes the 1960s didn’t get going until 1962, and we were starting from scratch (making how the 1960s ended in Flushing even more remarkable). And let’s acknowledge that 1970 through 1973 represented a reasonably competent above-.500 quadrennium whose culmination, You Gotta Believe, couldn’t have been much more thrilling.

Since Wayne Garrett popped to Bert Campaneris to end the 1973 World Series, we haven’t been able to string together a strong four-year start to any Met decade. From 1980 through 2023, the Mets have contested twenty seasons that have ended in the numbers 0, 1, 2 or 3 — or 21, if we take the split seasons of 1981 into account. The Mets posted a winning record in four of them. There was one pennant in there, in 2000; one additional playoff spot, in 2022; one end-of-an-era shortfall, in 1990; and one that we’ll call, considering its September’s circumstances, a nice try, in 2001.

The early 1990s completely got away after 1990, with 1991 a cavalcade of misery a Mets fan couldn’t have imagined would be surpassed not once but twice over the next two years. The residual good vibes of 2000 all but disappeared until late in the 2001 season, at which point it was probably asking too much of the Mets to see to fruition their attempt at coming to their city’s emotional rescue — after which, 2002 was essentially 1992 redux, and 2003 was its own kind of pits.

And those were the decades, besides this one, that had at least one decent year within their four.

When I think of what might become of the 2020s, I try to remind myself that the 1980s went 0-for-4/0-for-5 out of the gate, yet when we think of the Mets of the 1980s, we don’t think at all about how bad the Mets of 1980, both 1981s, 1982 and 1983 were. The Mets of the 1980s as they exist in the popular imagination materialized nearly fully formed in 1984 and rode high right up to the doorstep of the 1990s. The Met version of the 1980s was the era that was ending when the 1990 Mets made one last charge at glory. It never occurred to us until August of 1991 that Excellence Again and Again, as the marketing theme went, wasn’t going to be a perpetual way of life, and it probably didn’t sink in until May of 1993 that a fan should take nothing for granted, certainly not an era’s ability to self-renew and extend itself indefinitely.

Decades are too long to wholly reflect the quality of a baseball franchise. Ten years leaves ample room for ups to overtake downs and vice-versa. If you invoke the Mets of the 1970s, you won’t evoke warm fuzzies for the best parts of 1970 through 1973. The decadesque definition of the ten years in progress fifty years ago got swallowed up by the rest of the 1970s, especially the Grant’s Tomb motif of its final three seasons. If a person wishes to define a team’s decade as “good” or “bad,” making a judgment 40% of the way in is why they put erasers on pencils.

Our 1990s plodded along until they could pull themselves up by their bootstraps circa 1997, and proceeded to give us a most compelling final act by 1999, though I don’t know whether the Mets of the 1990s stand more for the explosion wrought by the Grand Slam Single or the explosion wrought by Vince Coleman’s taste for parking lot firecrackers. The Mets who were withering at mid-decade in the 2000s discovered new life in the second half of what people insist on calling the Aughts (I preferred Ohs), but the life oozed right out of the party by 2009. As for the 2010s…

Ah, the Mets of the 2010s, the last decade before this one. That’s the one I find myself thinking about most vis-à-vis the 2020s, and not just because of adjacency. In dwelling on the early 2010s recently, I came to label the period when we were getting used to Citi Field the Hump Years. This was after the brief glory of 2006 morphed into the lingering bitterness from the collapses of 2007 and 2008, the culture shock of having Shea’d Goodbye, and the entire Metsian enterprise being hamstrung by the Madoff Affair — and before 2015 tickled our sadly neglected fancy. Rooting for non-winning Mets clubs through 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014, we persevered in hopes that some year soon, we would get over the hump. The hump cast a mighty long shadow on our enthusiasm. Glints of happy distractions might speckle the landscape now and then, but the collective benefits from an intermittent array of individual accomplishments didn’t feel like it was making the slightest dent in that goddamn hump.

Yet we got over it, or around it, or did something indicating meaningful success had at last been achieved come October of 2015, and things got happy and stayed fairly happy for a year or two. Then they got largely unhappy for a couple of years. Then, in the latter stages of 2019, they verged on happy when we no longer dared expect happiness.

Then the 2010s were over and the 2020s were here and, as we approach the Baseball Equinox that precedes this decade’s fifth season, I’m in a Met headspace that feels familiar from ten or so years ago. I feel like we’re behind another hump, which was an object I would have presumed was consigned to my rearview mirror rather than my front windshield had I permitted myself to make presumptions.

2020 was sixty games in empty ballparks that I sort of wish hadn’t been bothered with. The Mets went 26-34.

2021 had the Mets in first place from May until August with the Mets hardly ever feeling like a first-place or playoff team. The Mets went 77-85.

2022 wiped away every scintilla of ennui from the previous two years as — under the guidance of a real manager and through the resources of a real owner — we romped to a tremendous start and built a monumental lead. We not only felt like a first-place team, we were a first-place team. But the Braves were as well, except more so, and the part where we went to the playoffs as a 101-61 Wild Card only rubbed it in more that we didn’t win our division. As a result, I have about as much affection for our participation in the 2022 postseason as I do for the sixty games in empty ballparks from 2020. Still, 101-61 wasn’t chopped liver, despite the pâté September and October turned into.

2023 disintegrated on contact. The real manager didn’t make it out in one piece. The real owner is still fine-tuning. The closer we get to 2024, the less it feels like the fun parts of 2022 ever happened. The Mets went 75-87. Spread it on a cracker.

The presence of Steve Cohen still gives me hope that humps can be scaled, traversed and ground to dust. The presence of David Stearns I will trust is a long-term positive in an endeavor where the terms seem shorter and shorter. I’m not invested in the new manager as of yet, but sure, why not him? A few core players and a couple of the youngsters form my contemporary rock; at least I have them. Everything and everybody else seems up for grabs. I’d like to be more stoked that once we pass 3:26 AM EST on December 30, we will be closer to the next season than the last season, but I’m nowhere near worked up over the coming of the next season. Fortunately, the next season has next season and the seasons after that to definitively alter my outlook.

The penultimate episode of National League Town for 2023 revisits 1973, because who the hell wants to revisit 2023?

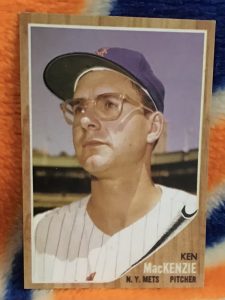

by Greg Prince on 16 December 2023 6:20 pm You might know Ken MacKenzie was the only Met pitcher to post a winning record in 1962. As calling-card facts go, it is distinctive and enduring and, within the context of a team that inspired its beat writers to track what Leonard Koppett dubbed the “neggie” or negative statistic (like the Mets’ failure to win a single game on any Thursday), unusually upbeat. Less commonly referenced is that Ken was also the only Met pitcher to post a winning record in 1963, a year during which he was traded, and that no Met pitcher who remained or emerged in 1964 posted a winning record. For three seasons, Ken MacKenzie provided the only concrete evidence that the Mets could win more than they lost.

Few are the Original Mets who symbolize winning in orange and blue, but you can’t take away from Kenneth Purvis MacKenzie his distinction, nor would have Ken, who passed away Thursday at age 89, downplayed his association with our tribe. If you trailed a vehicle tooling around the Tri-State Area with a Connecticut plate reading 62 MET in recent years, you were following in the tracks put down by the automobile of Ken MacKenzie.

One day after stocking the prospective Original Mets with 22 personnel possibilities from the 1961 expansion draft, George Weiss returned to his shopping and purchased Ken’s contract from the Milwaukee Braves. The lefty reliever became a member of Casey Stengel’s very first pitching staff, the one that broke camp in St. Petersburg, flew to St. Louis to begin the franchise’s official existence, and came home to the Polo Grounds to reinstate National League baseball in New York. Ken’s Met debut occurred on April 15, 1962, the club’s fourth game ever. Curiously, the native of Gore Bay, Ontario, was the second Canadian in Mets history. Ray Daviault, who pitched in the Home Opener on April 13, hailed from Quebec.

The Mets reserved two spots for pitchers from the Great White North, yet they were heading south at a precipitous rate. The Mets’ first nine games resulted in nine losses. MacKenzie worked in three of those, though he steered clear of any deleterious decisions himself until May 4, when he took the L in a 6-5 defeat at Philadelphia. But Ken’s days would come.

Ken’s calling card was unique for New York in 1962. The first of them arrived May 19 in Milwaukee, versus the team that sold him to the Mets. Ken let the Braves know he remembered them by throwing a pair of scoreless innings that culminated in retiring Hank Aaron on a grounder to short. The Mets were behind, 5-2, when MacKenzie entered, and he hadn’t extended their deficit a whit in the sixth and seventh. Holding the fort can be fortuitous, and so it was this Saturday in Cream City. Another ex-Brave, Frank Thomas, tripled to lead off the visitors’ eighth. A rally commenced. Down 5-4, Stengel pinch-hit Richie Ashburn for Ken. Whitey came through with a single. Charlie Neal crossed the plate. The game was tied. Jim Hickman then batted with one out and delivered a sac fly to score Rod Kanehl. Ken MacKenzie was the pitcher of record on the long side. Craig Anderson nailed the final six outs.

The Mets were 10-19, or 10-10 since losing those first nine. Ken MacKenzie was 1-1. Having tasted variations of .500, Kenny and the Mets the very next day decided they wanted more out of life. Being the Mets, they’d have to struggle for it. They trailed the Braves, 5-1, at County Stadium in the seventh when MacKenzie came in once more. The seventh inning on May 20 reflected his success of the day before, with Ken striking out Aaron again. The Mets trimmed the Braves’ lead in the eighth to two runs and stuck with their lefty in the bottom of the inning. Ken did not give up a run. In the top of the ninth, Casey again pinch-hit Ashburn for MacKenzie. Ashburn again singled, sparking a four-run uprising that vaulted the Mets into a 7-5 lead. Anderson again came on to protect what Ken had constructed. This time it wouldn’t be easy for Craig, as Hammerin’ Hank doubled home his brother Tommie, but the Mets held on to win the first game of this Sunday doubleheader, 7-6, and they’d grab the nightcap as well.

The Mets were in the midst of their very first three-game winning streak, and Ken MacKenzie was 2-1. “The darlings of New York — an odd-lot collection of expendables,” reported Bob Green of the Associated Press, “suddenly are the hottest team in baseball.” The relief pitching Stengel was getting from Ken, among others, was proving a “thorough-going pleasure,” according to Dick Young in the Daily News. For the briefest of instances, despite Green’s assessment that “there is still an air of the Keystone Cops about this crew that lost nine straight at the start of the season — they flounder about and sometimes run into each other,” it appeared the 1962 Mets would have to be taken somewhat seriously. They’d won nine of their previous twelve games and led two teams (Houston and Chicago) in the standings. “Somehow,” the man from the AP marveled, “Stengel, the old master manipulator, has them winning.”

Well, that didn’t last. A seventeen-game losing streak awaited as soon as the Mets left Milwaukee, and tenth place was a sure thing by the end of May, yet Ken MacKenzie was destined to make his mark in the other direction. On July 2 in San Francisco, Ken rescued Anderson for a change, setting down the Giants in order in the seventh inning after Craig turned a 4-1 Met lead (built at Juan Marichal’s expense, no less) into a 5-4 Met deficit. Another savvy pinch-hitting choice by Casey the master manipulator — this time Rod Kanehl reaching on an error as he batted for MacKenzie — contributed to a four-run eighth that provided the Mets the winning margin in an 8-5 triumph. Ken’s record was raised to 3-3.

The next victory in the MacKenzie collection was a doozy. Four innings of relief were punctuated by Ken himself singling in Joe Christopher to give the Mets a 9-6 lead, an insurance run that proved vital in what turned into a 9-8 final. With his arm and his bat, MacKenzie could now claim a 4-3 record.

Casey tried his lucky lefty as a starter in a Polo Grounds doubleheader on August 18. Not much luck for Ken in that capacity, and he’d be 4-4 by the time that game versus the Cardinals was over. Yet one more decision was in the offing as 1962 rolled on. The day that distinguishes MacKenzie among all Mets pitchers until 1965 (when Jim Bethke, Darrell Sutherland Dick Selma all finished over .500) is August 22, a home date versus the Giants. A home date versus the Giants in 1962 was no matter of playing out the string. San Fran was charging hard to catch up to L.A. at the top of the NL standings. And even if neither the Giants nor Dodgers was battling for a pennant, Mets fans remembered who left their town high and dry in 1957. “Every close Mets’ game against the Giants or Dodgers,” Stan Isaacs wrote in Newsday at the time, was tantamount to “another version of the ‘little World Series.’”

In this classic of the genre that drew 33,569 paying customers, the Mets led the Giants by three heading to the eighth. Alas, what Isaacs termed “the creeping dread of catastrophe” was also in attendance beneath Coogan’s Bluff. Bob L. Miller had handled the former neighborhood residents for seven innings, but Bob was burdened by an 0-10 record, and the Mets were 31-95 entering this particular Wednesday night, which is to say Met catastrophe didn’t necessarily creep in on little cat feet. Miller issued a pair of walks to start the eighth, then secured a groundout, then faced Willie Mays.

Facing Willie Mays didn’t often end fabulously for a pitcher, as Miller could attest after allowing an RBI single to the Say Hey Kid. The Giants were now down by two, they had two on and Orlando Cepeda due up. Miller time was over. MacKenzie time was at hand. Ken was a lefty, and Cepeda was a dangerous righty, but Casey had his reasons, all of them tied to his faith in the Canadian southpaw.

”He gets those righties out better than lefties and now he’s getting the lefties out. That man is getting close to being a big league player. I mean just because you’re playing for us don’t mean you’re a big leaguer, but he’s getting there.”

Which is great, except Cepeda singled to center to score Chuck Hiller and move Mays up to third, from whence Willie came home when the next batter, Felipe Alou, grounded out. The game was knotted at four. Bob Miller’s shot at getting his first win was erased by MacKenzie’s not so hot outing.

If Ken couldn’t preserve a win for his beleaguered teammate, he could at least make it up to the rest of the team. Stengel had MacKenzie bat for himself to lead off the home eighth. He made contact, which is so much better than striking out, because you never know what will happen when you put the ball in play. In this case, an error happened, charged to Giant second baseman Hiller. MacKenzie was on first, carrying the potential go-ahead run. Its potential grew in possibility when Casey replaced Ken on the basepaths with Joe Christopher. The Ol’ Perfesser called on pinch-runners 86 times in 1962, still the most in any season in Mets history. “With a chance to go ahead, Stengel operated like the master he is,” Isaacs observed. “He still makes the masterful moves with the Mets, but the boys just don’t ‘execute’.”

On the night of August 22, they did. Richie Ashburn drew a walk to advance Christopher to second, and Neal singled to drive speedy Joe home with the lead run. Up 5-4, and not taking an opportunity to beat a contender (or anybody) lightly, Stengel inserted Roger Craig to pitch the ninth. Roger Craig was the ace of the starting rotation in 1962, but what exactly was Casey gonna save him for that was bigger than this? Roger indeed notched the save…with defensive help from none other than Marv Throneberry at first. Following Jose Pagan’s leadoff single, Marvelous Marv made a nifty stab on a sharp grounder off the bat of Willie McCovey and started a clutch 3-6-3 double play that set the stage for the final out.

Isaacs, ever ready to interpret the deeper meaning of Mets baseball in its infancy, heard “a grown man in the upper right field stands blurt, ‘Oh boy, we saw the Mets beat the Giants,’” illustrating that “for people who are with it, these Met games are an experience over and above the mere pleasure of watching baseball. Grown men at Yankee games or My Fair Lady or Little Orchestra recitals don’t come away with the gleam in the eye of the man who exulted at the good fortune of having seen the Mets beat the Giants for the fourth time in seventeen games.”

Amid the enthusiasm attached to such an outcome, MacKenzie’s won-lost mark rising to 5-4 might not have seemed a particularly big deal. let alone rated an “oh boy”. Even in 1962, when pitchers were judged mainly by their accumulations of Ws and Ls, it was understood relievers sometimes happened to benefit from right place/right time syndrome to record their victories, particularly when a pitcher left a game trailing or tied after giving up key runs himself. Sometimes the pitcher on the hook sat back and enjoyed the fruits of his team’s offense making everything better and him a winner. “Vultured” is how those wins tend to be described. But it’s a long season, and teammates do pick up for teammates. This team was on its way to losing three times more often than it won, yet one pitcher on this team was the pitcher of record nine times and came away with one more win than loss on his ledger. If it was that easy to achieve, some other 1962 Met would have achieved something like it. None did.

Five-and-four was the record Ken MacKenzie would keep for the rest of 1962, and that’s the record by which he’d be recognized into baseball eternity. The 3-1 he cobbled together in 1963 would be less invoked as a piece of trivia, but, yeah, no other pitcher in the Mets’ second year had a winning record, either. Ken showed enough as a “big league player” to attract the interest of the contending Cardinals in the summer of 1963. St. Louis swapped Ed Bauta to the Mets to acquire MacKenzie while they were visiting New York. Ken had worn 19 as a Met. It was immediately issued to Ed. The pitchers themselves traded warmup jackets, with Ken shedding blue nylon in favor of red.

But Ken’s license plate nearly sixty years later didn’t read 63 CARD. He clearly relished his connection to that first bunch of Mets, and if being known as the guy who won for a team that made losing an art form was what people chose to remember, it beat being known as just another pitcher who lost a lot…or being mostly forgotten. He nodded along for decades when his other calling card, his status as the so-called “lowest-paid member of the Yale class of 1956,” was brought up to him. Going into professional baseball wasn’t a path to riches for an Ivy Leaguer or any leaguer back then. Embroidered within the legend of the first Yalie to pitch for the Mets (Ron Darling being the second) was Stengel’s advice to bear down against tough batters like he was facing “the Harvards”. Per MacKenzie, who would coach at his alma mater after retiring from baseball, that was no stray tossed-off trifle of Stengelese. Ken actually pitched very well against Yale’s archrivals, and MacKenzie said Casey knew that, much as Casey had a knack for knowing something about everything.

MacKenzie threw his first pitch in the majors for the Braves in 1960 and his last for the Astros in 1965. His tenure left him about a month shy of qualifying for the major league pension, and as a Yale alumnus not necessarily in the same league financially with classmates who pursued other endeavors, he put out feelers to his old teams in 1969, when he was 35, to see if there’d be room for him on the September roster in order to accumulate the requisite days he needed. He also checked in with the expansion Expos, given that they were ensconced in Montreal; he was Canadian by birth; and their enterprise was run by John McHale, who remembered him from their days together in Milwaukee, pre-Mets. McHale, operating a team that was going nowhere, brought Ken on board to finish out his career as an active pitcher. He threw only batting practice, but he earned his pension. He also had a pretty good seat for what had been unthinkable seven years earlier when he came into Shea Stadium with the Expos on September 10 and watched the Mets surge into first place. In 1962 and 1963, MacKenzie was the only Met with a winning record. In September of 1969, the Mets as a whole hardly ever lost. Despite wearing the uniform of the Expos, MacKenzie admitted to Isaacs he was quite happy for their opponents’ upturn in the standings. “I’ve always thought of the Mets as my team,” Ken said.

For the rest of Ken’s life, that sense of identity was clear, and not just if you saw his car. MacKenzie remained a generous sharer of stories about the Original Mets whenever he was asked to recall those days, a gift that grows in value when you realize there are only nine living Mets among the 45 who played for our team in 1962. They were just anecdotes, but they were the kinds of anecdotes that would otherwise disappear from the baseball discourse if he didn’t tell them. Pregame hands of bridge in which Ken and his pal Hot Rod Kanehl competed against two future Hall of Famers, Gil Hodges and Duke Snider. An unexpected compliment from batting coach Rogers Hornsby that “‘you’re not a bad hitter, you put the bat on the ball.’ And usually, he didn’t talk to anybody.” Ken would confirm, as best he could as the details blended into Met mythology, the old favorites about Yale, and going 5-4 when everybody else was going 35-116 combined. Historical retellings are ultimately copies of copies of copies once the source material is no longer within our grasp. Here was a primary source, still telling it like it was.

First to win more than he lost, first to be introduced 60 years later. When the Mets performed their biggest mitzvah as a franchise and invited back 65 of their alumni for a blowout sixtieth-anniversary celebration at Citi Field in 2022, the first Met returnee Howie Rose introduced was Ken MacKenzie. Ken had helped promote the revival of Old Timers Day all year, joining Jay Horwitz’s podcast over Zoom and granting a lengthy interview to the Hartford Courant. When the big day approached in late August, Jay later revealed, Ken checked himself out of the hospital to make sure he’d be there. He had to be wheeled to the foul line, but this Original Met wasn’t gonna miss this occasion.

A grown man in the upper left field stands that afternoon didn’t blurt anything in the moment, but he did applaud heartily, thinking to himself, in so many words, “Oh boy, I’m seeing the first Met to post a winning record.” There were, that grown man is certain, more than a few gleams in more than a few eyes when Ken’s name was called.

by Greg Prince on 13 December 2023 6:29 pm Aren’t we supposed to be immune to developing brand new sympathy pains for injured Mets players in December? Mets players aren’t supposed to get injured this time of year unless it’s something like what happened to Tug McGraw in the winter following the Miracle Mets’ world championship of 1969. In his 1974 memoir Screwball, Tug came clean on an ankle he twisted and reported to the club as the result of slipping on some ice while taking out the garbage. The injury was actually sustained as a result of tobogganing in snowy Syosset with Ron Swoboda, the two teammates sharing one toboggan. One of their rides didn’t go as planned, with Ron landing on top of Tug when it was over. Swoboda was OK. McGraw wasn’t.

“I had to sign my contract for the next season — it had just been mailed out by the Mets,” Tug remembered, “and I sure as hell didn’t want to tell them what happened, at least not how it happened. Especially since they thought we were nuts in the first place.” Thus, the cover story, which the Mets shrugged off as a hazard of bad luck and cold climes. Slipping on ice on Long Island is not uncommon (as I can vouch). Tug made it back to start the 1970 season and saved the Mets’ very first Opening Day win.

What befell Ronny Mauricio this past weekend while playing winter ball had the same luck component to it, though the weather was warmer. A baseball player got hurt playing baseball. That will happen. That it happened not for the Mets or a Mets affiliate but for Tigres del Licey in LIDOM competition…well, that, too, will happen. Mauricio tore the ACL in his right knee as he began to take off toward second base from first as a baserunner. He went down less than halfway toward his destination.

Ronny was honing his craft and the Mets were well aware of what he was up to. No whiff of scandal, not even WBC recriminations à la Edwin Diaz. As if that matters now. The injury will require surgery plus a recovery period that will prevent Ronny’s presence on the Opening Day roster or any Met roster for quite a while. This is a shame on several levels. Ronny’s been a Met prospect since approximately the year Swoboda was traded to Montreal, or so it seems. He’s only 22, but was signed at 16 and has ranked among Baseball America’s Top 100 up-and-comers since 2019. We got our first glimpse at his obvious offensive talent last September. A shortstop blocked by Francisco Lindor for the foreseeable future, Mauricio played a swift second base when he came up, a less sure third, the latter a spot that has no obvious Met occupant at the moment. Ronny will contend for neither position as 2024 gets going.

Sympathy abounds, of course, even if we were hoping to save it for the kid’s first slump.

by Greg Prince on 11 December 2023 5:59 pm I count fourteen players with major league experience the Mets have picked up in the past month or so. I feel I recognize five, maybe six of the names. I’ve probably seen a few others as Met opponents but forgotten them. A generous portrayal of their collective appeal would be they provide our team with depth.

Absolutely none of these names is exciting, but I’ll take it on faith that their presence in Spring Training on major or minor league contracts is necessary. Following the crummy 2023 season, the Mets shook out from their roster a bunch of players fans of other teams might not recognize. Depth replaces depth. Depth is what you call the players whose presence amounts to a dearth of excitement.

We are in the museum gift shop phase of the offseason. I love going to museums. I recoil at the sight of their gift shops, however, because once you’ve toured the museum, you are vulnerable to books and posters and whatever other tchotchkes the gift shop is offering for a fee. It’s all stuff that’s neat, but it’s also stuff for which you hadn’t any need or desire before you showed up at the museum. You still don’t have the need for it, but the desire can be overwhelming. “Can I really leave here without this thing, now that I know the backstory of this thing?” I try to confine my purchases to a refrigerator magnet and otherwise keep my hands in my pockets.

“I just gotta have this pitcher!” I didn’t know I desired Yoshinobu Yamamoto for the Mets until the Hot Stove tour guide mesmerized us with tales of the sensational pitcher. He’s thrown how many no-hitters? He’s won how many Japanese Cy Young equivalents? He’s only how old? His repertoire is how enticing? I was modestly aware of Yamamoto during the season, but now he’s the talk of the offseason, and I’d very much like him for the Mets’ collection…I mean rotation. His name permeates every 2024 Mets thought I’ve had lately, though such exclusivity is a little misleading. Other than the reports surrounding Steve Cohen and David Stearns flying to Japan to pitch the pitcher on pitching for the Mets, I haven’t much thought about anything specific pertaining to the upcoming season since the last one went away. Fourteen players with major league experience picked up, zero sparks given off. I can’t remember the last time I was less revved up for late March in mid-December.

Unless we get Yamamoto, who I have to have, the way I had to have Carlos Correa once it was clear we were getting Carlos Correa last December. We ultimately didn’t, but it was a pretty exciting thing to think we did, best deals sometimes being the ones you don’t make notwithstanding. We’re not quite in Correa to the Mets territory yet, let alone Ohtani to the Jays. Ohtani to the Jays was so much in the atmosphere that a Canadian front pushing down from Ontario was evident on weather apps all over North America. Except Shohei Ohtani signed with the Dodgers (boy, did he ever). I’m figuring Jays fans are a lot sadder about not getting their man than I’ll be if we don’t get our man. Unless Yamamoto’s flight into LaGuardia is tracked by reputable sources. Then all emotional bets are off.

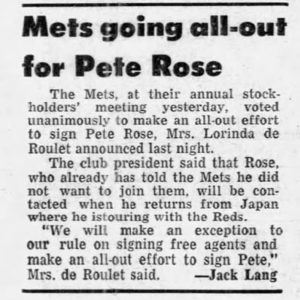

Spoiler alert: Mets did not get their man. I’ve been focused enough on Yamamoto to the Mets that I never devoted a byte of bandwidth to considering Ohtani to the Mets, other than knowing it wasn’t absolutely beyond the realm of possibility. With Steve Cohen, the Mets emerging as the choice of a player who winds up commanding $700 million over ten years is never beyond the realm of possibility. I know we’ve signed our share of glamour pusses in recent winters, but deep down, I view free agency as an excuse for stars the caliber of Reggie Jackson and Pete Rose to laugh off our feelers, instinctively flashing back to when baseball’s open market was very new and the Mets were acting very old. In the 1979 free agent re-entry draft, the system under which teams had to select negotiating rights to players, the Mets tossed their names in on mid-level availabilities Rennie Stennett, Rudy May, Bruce Kison, Greg Gross, Don Stanhouse, Rowland Office, Jim Wohlford and Roy White. None of those fellas was flattered enough by the attention to be swayed toward Shea. If memory serves, one of them huffed that if he wanted to play in New York, why would he ever choose the Mets? That’s what winter used to be like around here. It’s my version of insisting we walked to school through two feet of snow.

We’ve come a long way, baby, albeit in theory this offseason. Sometimes just being mentioned in the fifth paragraph as a place a player like Ohtani could go is tantamount to a fleeting Hot Stove moral victory. Those times are when you’re thinking to yourself, “Look how much we saved that can now go toward Yamamoto.” Meanwhile, Yamamoto has flown to the U.S. and is said to be talking with multiple teams on both coasts. His price is no doubt being driven up, but the gift shop isn’t closed until it’s closed.

by Greg Prince on 8 December 2023 4:02 pm Met offense is moping along as Met offense has made a habit of doing since its founding in 1962. Then amid the mopery emerges some genuine hope in the form of a Triple-A outfielder who brings to New York a bat loaded with hits, making things a little less mopey, at least for a spell. Mike Vail is the most extreme example of this phenomenon, D.J. Stewart the most recent.

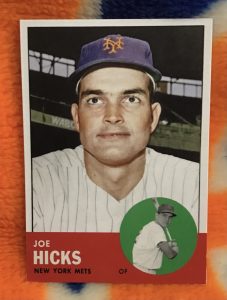

Joe Hicks, who died on December 2, stands out as the first.

Hicks was called up to the Mets from Buffalo shortly after the All-Star break in 1963. The Mets finished the first half on a ten-game losing streak and began the second half by losing five more. All help was welcome. All help began to make a difference on July 15 when, in Hicks’s third start as a Met, Joe doubles in a run in his first at-bat. Two batters later, pitcher Carl Willey launches a grand slam. Hicks will also single a run home in the fourth and single once more besides. Three hits, two runs, and the Mets are 14-5 winners over the Colt .45s in the opener of a doubleheader at home. Losing streak over. Hot streak begun.