The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 24 November 2023 2:42 pm My friend Matt Silverstone. It feels good to write that. It doesn’t feel good knowing I’m writing it because I recently did a little curiosity-driven Internet snooping and discovered Matt died eight years ago. I seem to run into that situation when I start to wonder whatever happened to some old friend of mine with whom I long ago lost touch. Matt and I last got together in 1991, for lunch. Never heard from him again. I’m in time-shifted mourning.

We met when we were twelve. The junior high side of twelve. It’s an important distinction. Elementary school was well over. We were a matter of weeks past the age of absolute innocence if we use the movie Stand by Me as our guide. “I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was twelve,” Richard Dreyfuss as the Stephen King stand-in says at the end. “Jesus, does anyone?” The narrator had been recalling the summer when he and his three best friends went out in search of a dead body. That doesn’t sound like something I would have been into doing the summer I was twelve. By the summer I was fifteen, I imagine Matt could have talked me into it.

Matt was the first friend I made in seventh grade. I don’t remember what brought us together. Probably proximity in the same homeroom. Homerooms were determined alphabetically. My last name was the first to be called for the back of the alphabet in seventh grade. If there was one more kid named “Sullivan” or “Weinstein,” I may have wound up in another homeroom and maybe Matt and I wouldn’t have come into contact in quite the same manner. Or maybe we got chummy in math class and it was destiny. As for what drew us into hanging out, he said something amusing and I laughed is my guess. Or the other way around. Matt was a good listener. He was also innately funnier than I was. Wry and dry. I’ve been trying to remember some of the hilarious things he said all the years I knew him so I can quote him and illustrate that he was one of the funniest people I ever knew, but I think it was mostly delivery.

In ninth grade, there were two guys in one of our classes who, for lack of a more precise term, we’ll label preppies. This was before “preppies” were a thing, but go with it. One of them called out to the other about nothing of note, maybe a little too excitedly. Matt watched them interact and pegged them to me as “the gold dust twins,” no further elaboration. None needed. I laughed for about three weeks.

Anyway, in the fall of seventh grade we got to talking, and it became habitual. I went over to his house on a Saturday, which seemed an exotic thing to do, given that he lived on the other side of town. On that first trip I met his parents and his baseball cards. He wasn’t all that interested in either entity, but I knew who his father was before I ever knew Matt. His father was Lou Silverstone. If you read Mad magazine in the 1970s, you recognized the byline. Yes, Matt would confirm to those who would ask, that was his dad. It didn’t seem to impress him much. Lou didn’t seem terribly impressed by himself, either. He was low-key friendly, a good match for Matt’s Canadian-born mother. I aged out of the Mad habit as junior high went on, but I’m still grateful that when we were in high school Lou slipped me a complimentary copy of the issue with his parody of The White Shadow in it. He seemed particularly proud of that one.

Matt didn’t slip me any complimentary baseball cards from his collection, but I seem to recall we worked out a reasonable price for a stack of his otherwise neglected 1970 Topps, particularly some Seattle Pilots I was suddenly yearning for in November of 1975. I learned early on that while Matt was pro-Mets in that way kids on Long Island grew up being then, he wasn’t much of a sports fan. He wore a New York Giants hoodie to school, which caught my eye since I didn’t know too many other Giants fans. He shrugged that his grandmother gave it to him.

Some of the cards Matt didn’t sell me and other flammables became subject to Matt’s experiments with matches and rubber cement up in his treehouse. I’d never before been in a treehouse and, other than Matt’s, I haven’t been in one since. I didn’t know treehouses actually existed outside comic strips. It served as Matt’s pied-à-terre, where he could take a friend from the other side of town and burn things in peace. There was a bit of a rebellious or nihilistic streak to Matt. He didn’t have much use for the conventions of polite society. Maybe he grew tired of answering the same questions about who his father was or what it was like to be as tall as he was. Burning cardboard in the treehouse was one of his ways of going off the grid. Rubber cement, I learned from him, made for effective lighter fluid.

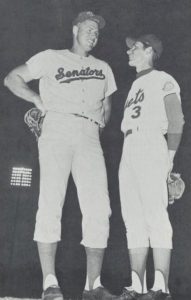

I waited this long to mention Matt’s height. He was a head or more taller than most everybody in junior high, 6-foot-6 by high school. He appeared mature enough so that on the first day of tenth grade, a vice principal told him in all earnestness he shouldn’t be sticking around this building anymore now that he’d graduated. I had decent height, enough to be placed in the back row of class pictures. Matt was the kid who was always directed to the center of that row. It must have gotten tiring to be reminded, when nobody had anything else to say, that he was unusually tall. Kids are good at pointing out physical differences. I’m pretty sure I never commented to him that he was tall. Maybe that’s why we stayed friends.

Matt did go out for basketball. Rode the bench mostly in JV, then on the varsity our senior year. He was just enough of a jock to make it work for him; he liked to surprise-punch me in the arm, as if that was something friends did. I never got mad at him for it, but that shit hurt. His game was being tall. Once in a while I’d get caught up in some schoolyard two-on-two with him versus any comers who wandered by. I wasn’t much good, but was usually willing to throw myself into it for a few minutes. Matt was a splendid teammate. Introduced me to the phrase, “Let’s kick some ass.” I’d heard others threaten to kick “your” ass (or my ass), but never with “ass” used as a non-specific object of kicking. I thought he made up the term.

I attended Matt’s JV games, which were usually sad affairs in that they were played after the varsity ones, which meant the gym cleared out and it was me and Matt’s parents representing maybe a quarter of the crowd. Matt, in turn, came to my school plays and made himself available to deliver copies of the school paper to various classrooms at my request when I was editor. From 1979 to 1982, he joined me at one Mets game annually, always into the experience if not deeply invested in the outcome. We supported each other’s endeavors and formed what amounted to our own social or antisocial circle. Matt didn’t not get along with anybody, but he was allergic to adolescent niceties. If “everybody” was doing it or watching it or talking about it, Matt wasn’t terribly interested in it.

As ninth grade drew to a close, what Matt wanted to do most was cut class. Like treehouses, that was one of those things I’d heard of but didn’t know was something that really existed outside of teachers warning against it. Matt talked me into joining him, probably to our shared detriment. I was very much on the bubble when it came to passing biology with the Regents on the horizon, and the biggest cutting-class call of all was not going to a review session that I, maybe both of us, could have used; my mother certainly believed I should have been there. Then again, it wasn’t mandatory, and we had our bikes, and we were riding on the boardwalk early on a June afternoon when those other suckers were stuck in school trying to remember which ventricle did what. Let’s just say I scraped by in bio and just now had to Google “ventricle,” whereas I’ll never forget that day on the boardwalk.

Having led me astray at the end of ninth grade, Matt set my agenda for the summer that followed. A lot of bike riding. He was really into bikes, especially fixing up old ones, including one for me. A lot of going to the beach, which was never something that appealed to me a ton once my family installed central air conditioning, but this was our dead-body summer, when Matt was expert at talking me into whatever. Without having to sell it, Matt convinced me everything we did was exactly what we should have been doing, even if it was stuff it wouldn’t have otherwise occurred to me to do, even if it was stuff I knew Matt shouldn’t have been doing. For example, Matt purchased from a classmate for twenty dollars and carried around a switchblade. I write that now and I wouldn’t blame you for expecting Blackboard Jungle to break out, but no rumbles were on the horizon. It was just Matt’s process for defying whatever might be expected of an exceptionally tall if otherwise average suburban ninth-grader going on tenth. He mostly liked to talk about the knife, as if he was keeping it handy for show ‘n’ tell (he gave it a name — Boopsie, I think, derived from Betty Boop). The only cutting he was gonna do was of class. The whiff of danger was enough.

I believe my role in Matt’s life as junior high was becoming high school was to be the kid who wasn’t remotely dangerous. Matt’s parents seemed to appreciate he had one friend who didn’t seem like the type to sell him a switchblade.

Midway through college, Matt transferred to a school on the East Coast of Florida. I was on the West Coast. He had his parents’ old Chevy Malibu and treated it like his bike, not hesitating to go out for a long ride, in this case to my side of the state. He’d call me on a Saturday afternoon and tell me to get ready for his arrival. I didn’t tell him no, and a few hours later he’d appear. This was during Matt’s would-be Lothario phase. Like with the switchblade, it made for better talk than action, which was just as well based on his patter. We’d run into a couple of girls I knew on the dorm elevator and he’d turn on the charm. The girls would laugh and exit. I’d cringe. He’d be undeterred.

I’ve been blackout drunk once in my life. It was one of those weekends Matt showed up. His advance instructions were for me to furnish gin. He’d bring tonic to make gin and tonics and then we’d go out. I’d heard of gin and I’d heard of tonic and I’d heard of them mixed together. I had never partaken. But if Matt is driving all the way over from the East Coast, I’d hate to be a bad host. Plus there was a party that night at the dorm that didn’t require any driving, so I guessed it was OK to have a few. I went to the Albertson’s liquor store, I picked up the distilled spirit in question, and we made gin and tonics, regardless that neither of us was adept at measuring gin versus tonic. Beyond cringing in the elevator at his rap (“hey, we’ve got gin and tonics in Greg’s room”), what I mostly remember is waking up after midnight on my roommate’s bed muttering about how “what I really want is to be in love,” and Matt listening to this without judgment. I’d be sober enough soon enough to give him directions to the 24-hour McDonald’s on Fowler Avenue, which is where one would go after adding too much gin to the gin and tonics. The next morning, he wakes me up bright and early so we can drive to Clearwater Beach, a spot he assumed I knew the location of. Only vaguely. I wasn’t any more of a beachgoer in Florida than I was in Long Beach unless Matt called.

Our last lunch was a half-dozen years after college. We’d kept in touch, but didn’t see each other very much. He was working in the same North Shore town I was, so it was convenient. I told him about a Mexican restaurant, and he was very much that’s it, that’s the place where we have to go, Mexican food absolutely. There was a little Damone from Fast Times at Ridgemont High to Matt: act like wherever you are, that’s the place to be. Setting baseball cards ablaze in a treehouse. Riding bikes on the boardwalk when we were supposed to be reviewing biology. Mixing gin and tonics like total amateurs. Mexican for lunch. I’d known Matt for sixteen years by then. It was a blast being reintroduced to his moves.

This was the summer of a bit of upheaval at my magazine, with an editor coming in who I didn’t necessarily trust. I droned on quite a bit during lunch about whatever indignities I perceived were being foisted upon me. Matt listened, because Matt was good at listening, though I had the sense it might have been a bit much with the droning on my end. Regardless, when we returned to my office for a few minutes after lunch and I introduced him to the momentary bane of my existence, Matt used all of his six feet and six inches to seem intimidating on my behalf. Later on, the editor and I would work out our differences and we remain friends to this day. At the time, however, the guy confessed he thought Matt was gonna kick his ass for me.

My wedding was a few months away at that point and I told Matt to be on the lookout for an invitation. I don’t think I ever got an RSVP. I was disappointed, but not surprised. The same scenario played out for my Bar Mitzvah. Matt didn’t really go in for those things. He did agree to be a groomsman at my sister’s wedding mostly because he assumed there’d be bridesmaids to work his charms on. I don’t think he signed my high school yearbook, either. That was Matt being Matt, I decided. Matt being Matt made him one of my favorite people ever. Matt being Matt also made me not reach out beyond 1991. I don’t want to bother somebody who doesn’t care to be bothered. I’ll see him when I see him, I figured, but I never did see him again. He didn’t show up for the two high school reunions I bothered with, and I knew damn well he wasn’t a social media person. I made cursory searches a few times, anyway. No dice.

His father I did bump into a few times, on the LIRR in the late 1990s. Lou had moved from Mad to Cracked as one might in his field. Became its editor, in fact. Matty was doing fine, he said, he’d send my regards. Lou died at 90 in March of 2015, the same year my father took ill. Eight months later, my recent rabbit-hole exploration revealed, Matt — married with two children and living one county east of me — died at the age of 52, apparently from cancer, which seems to have taken too many of my friends from my youth, guys with whom I was no longer in contact but had never forgotten. Matt was certainly unforgettable to me, down to my bones. My arm still hurts thinking about him.

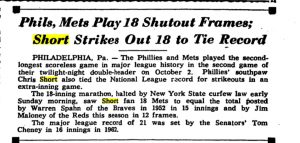

by Greg Prince on 22 November 2023 2:01 pm “I call to order the 2023 meeting of the Faith and Fear in Flushing Awards Committee for the purpose of selecting the Richie Ashburn Most Valuable Met for the season just past. Before we proceed, is there any old business?”

“Yeah — who did we name last year?”

“Uh… Starling Marte.”

“Wow. That doesn’t look very visionary a year later.”

“Perhaps not, but FAFIFAC isn’t in the business of forecasting. It’s in the business of reflecting.”

“Still, I’m beginning to wonder if there’s a FAFIF MVM curse. Who did we give the award to the year before last?”

“Uh… Aaron Loup and four other relievers who pitched a lot and pretty well.”

“Loup? He was gone the next year.”

“C’mon. One of the other relievers in that writeup was Edwin Diaz.”

“The Diaz who got hurt during Spring Training this year?”

“Well, it wasn’t Yennsy Diaz.”

“Ohmigod, we really are putting a curse on these guys.”

“Nonsense. We gave it to Jacob deGrom three times.”

“And look at him now. Missed most of the year and won’t be back until who knows when.”

“We also gave it to Beltran, Wright and Reyes, and they’re all on the Hall of Fame ballot.”

“See? None of them is still playing. Maybe we prematurely ended their careers.”

“Let’s get serious about this season. How about a nomination for the Most Valuable Met of 2023?”

“I nominate Nobody.”

“You really believe this curse business?”

“No, I’m saying that after a year like 2023, it’s clear that Nobody was ‘most valuable’ to the Mets, certainly not valuable enough to make any kind of difference.”

“We can’t do that.”

“Why not?”

“Because we don’t do that.”

“That’s not an answer.”

“It is in this case. We’ve given a Most Valuable Met award since the end of our first season in 2005, no matter how not good the season was.”

“I know. But has any season felt less valuable than the one we just got through?”

“I never thought of it that way.”

“Think about it.”

“I have. And you’ve got a point. Twenty Twenty-Three felt uniquely lacking in value while it played out and I have little desire to revisit it in granular form.”

“Great. So we’re agreed that our Most Valuable Met should be Nobody. Can I get a second?”

“Hold on. We don’t do that.”

“You already said that.”

“And I’ll keep saying it. Every baseball season, even the shortest and least inspiring, has its most valuable players, and even the lamest Met years have their most valuable players. We always come up with somebody because somebody inevitably stands out. Remember, we named the award for Richie Ashburn because the beat writers voted Ashburn the first Mets MVP in 1962, and that team lost 120 games.”

“Fine. But just so you know, to me, the MVM of 2023 is Nobody.”

“Duly noted. Now let’s get serious. Who’s our Most Valuable Met?”

“I don’t know. Lindor? Senga?”

“Yeah, that’s pretty much what I was thinking.”

“Which one?”

“Both, with Francisco Lindor and Kodai Senga sharing the designation as Faith and Fear in Flushing’s Richie Ashburn Most Valuable Mets for 2023.”

“Great. Move to adjourn!”

“Wait!”

“What?”

“There’s got to be more to it than that.”

“Why?”

“Because we do that.”

“These are your reasons? ‘We don’t do that.’ ‘We do do that.’”

“Baseball is defined by its traditions, and it is our tradition to celebrate our MVMs.”

“Can’t we start a new tradition of getting it over with? Like we wished the 2023 Mets had simply gotten their season over with?”

“Hmm…that would embody the spirit in which the 2023 Mets season played out.”

“Glad you see it my way. Move to adjourn!”

“Not so fast.”

“Never so fast with you. Why can’t we adjourn?”

“Listen, an entire season of Mets baseball was played, and we’re here to honor the two Mets who were not only here from the beginning of the season to the end — which isn’t something too many Mets could say — but two Mets who excelled from beginning to end.”

“I seem to recall Lindor slumping for a while.”

“Everybody slumps.”

“Wasn’t there a pop fly he didn’t catch?”

“Everybody makes mistakes. He was nominated for a Gold Glove, for cryin’ out loud.”

“His batting average was pretty low in the middle of the season.”

“It rose in the second half, and he was never not productive. More than a hundred runs scored, nearly a hundred runs driven in, first Met in the 30-30 club since Wright — and he won the Silver Slugger! First Met shortstop since Reyes to do that.”

“Senga barely qualified for the ERA title.”

“But he did, in fact, qualify. Finished second in the National League in that category, same place he finished in Rookie of the Year voting.”

“He pitched professionally in Japan for more than a decade. Was he really a rookie?”

“In the eyes of MLB, he was. We’ll take their word for it.”

“That bit where he always needed extra rest never sat right with me.”

“Call it an adjustment period. You change countries, rely on an interpreter and get batters out for six months.”

“Had some bad outings.”

“Had many more good outings, especially as he got used to pitching in the majors. The Mets won seventeen of his twenty-nine starts, and this wasn’t a team that won nearly enough of anybody’s starts.”

“I couldn’t help but notice that on the night both Lindor and Senga were being toasted for reaching their individual milestones — Senga becoming the first Met rookie since Gooden to strike out 200 and Lindor belting his 30th home run to make himself 30-30 — that the Mets lost.”

“So?”

“So it sort of symbolized for me the futility of this team that its two most valuable players couldn’t push it over the top in the game where they were lauded for personal stuff.”

“That’s a highly selective interpretation.”

“Well, we are a selection committee.”

“As a responsible selection committed, we’re looking at a much broader body of work. Lindor missed all of two games in 2023. Two! Senga, even with the rotation accommodating the extra rest that he functioned better with, never missed a start. They posted up and then some. Some years that really stands out.”

“If you say so.”

“I do say so. And now I need you to say so.”

“Fine. Here’s to our co-MVMs of 2023. If they weren’t necessarily more deserving than Nobody, they were certainly way better than nothing.”

“I’ll take that as a ‘yea’ vote for Lindor and Senga.”

“Yay. I mean ‘yea.’”

“Move to adjourn.”

“Seconded.”

“The 2023 meeting of the Faith and Fear in Flushing Awards Committee for the purpose of selecting the Richie Ashburn Most Valuable Met for the season just past is now adjourned. We will reconvene in short order to consider candidacies for the 2023 Nikon Camera Player of the Year.”

“Yay.”

FAITH AND FEAR’S PREVIOUS RICHIE ASHBURN MOST VALUABLE METS

2005: Pedro Martinez (original recording)

2005: Pedro Martinez (deluxe reissue)

2006: Carlos Beltran

2007: David Wright

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Pedro Feliciano

2010: R.A. Dickey

2011: Jose Reyes

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Daniel Murphy, Dillon Gee and LaTroy Hawkins

2014: Jacob deGrom

2015: Yoenis Cespedes

2016: Asdrubal Cabrera

2017: Jacob deGrom

2018: Jacob deGrom

2019: Pete Alonso

2020: Michael Conforto and Dom Smith (the RichAshes)

2021: Aaron Loup and the One-Third Troupe

2022: Starling Marte

Still to come: The Nikon Camera Player of the Year for 2023.

Here right now: A new episode of National League Town.

by Greg Prince on 18 November 2023 5:56 pm To properly commemorate what would have been the 79th birthday of Tom Seaver on Friday, the New York Mets made a gift of Daniel Vogelbach’s availability to anybody who wants him. Technically, it was a non-tendering, but a gift is a gift. Vogelbach’s status as beloved Met who could deliver a hit on demand was brief. He definitely wasn’t as good as we thought in the wake of his 2022 arrival, probably not as bad as we collectively decided by the time 2023 went to hell. He very much rates a live-and-be-well farewell, at least until he goes all Travis d’Arnaud on our ass.

Joining Vogey in the land of fresh opportunity is Luis Guillorme, whose six-season tenure as a utilityman outlasted its utility by roughly a year. When he and the Mets peaked together, in the first half of ’22, Luis was Buck Showalter’s “regular irregular,” catching every ball hit near him and hitting plenty of the balls pitched to him. With defensive dexterity that earned him the nickname Los Manos, Guillorme casually nabbed a flying bat (the wooden kind) while standing in the dugout one Spring Training, and worked an at-bat as epic as his beard in another Spring Training. Perhaps Luis would prefer a stream of impressive black-ink statistics to show off to prospective employers this winter, but there’s something to be said for being enough of a legend that fans will warmly remember who you were long after they’ve forgotten what numbers you didn’t post.

Also enveloped in the non-tendering agate type are three relief pitchers — Jeff Brigham, Sam Coonrod and Trevor Gott — who call to mind the Wolf’s description of the body that needs to be disposed of ASAP in Pulp Fiction: nobody who’ll be missed. This troupe of freshly minted free agents joins a slew of other 2023 Mets who’ve been brushed aside by recent roster machinations. For those who haven’t been paying utmost attention to minute detail, Anthony Kay and Vinny Nittoli were grabbed by the vagabonding/Vegas A’s in October, while out on the open market just in time for holiday shopping are (deep breath) Rafael Ortega, Jose Araúz, Michael Perez, Danny Mendick, John Curtiss, Denyi Reyes and Tim Locastro. Carlos Carrasco left of his own expired-contract volition and Adam Ottavino declined his player option, citing a surfeit of Met uncertainty. Player churn happens every fall. Factor in new management, and the the exit velocity where old players are concerned is bound to be accelerated.

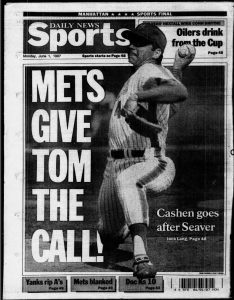

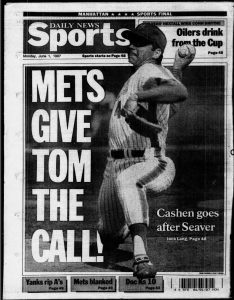

For all we know, one or more of the above will be back with the Mets sooner or later. We didn’t know Tom Seaver would be back with the Mets when he was traded on June 15, 1977, but there he was, striding in from the bullpen on April 5, 1983. We didn’t know Tom would be back with the Mets when he was swallowed up in the ill-fated compensation pool on January 20, 1984, but there he was yet again on the morning of June 6, 1987, putting on a Mets uniform and talking to Bob Murphy.

Could a comeback be any more official?

I recently stumbled across an audio gem. It’s from the Mets radio pregame show that bridged Mets Extra and Mets baseball from the first Saturday in June 36 years ago. Murphy hosted, Seaver guested. Tom was in orange and blue not for ceremonial purposes, but to take one more shot at pitching…and because the Mets weren’t giving up on contending.

Sometimes everything is about context. That morning in Flushing, the New York Mets were defending world champions, but their title defense hadn’t been going so swell. They were a fourth-place team, one game above .500 and six games from the top of their division. Yet there was hope. The night before marked the return of Dr. K. Dwight Gooden missed the first two months of the 1987 season after being directed to rehabilitation after testing positive for cocaine late in Spring Traning. One month in drug rehab at the Smithers faciity in Manhattan, one month in what amounted to pitching rehab, getting his arm back into shape in the minors. The former may not have been enough for a person with an addiction, but the latter seemed to have its intended effect. On June 5, 1987, Doc was on the mound again at Shea Stadium, holding the Pirates to four hits, four walks and one run over six-and-two-thirds innings in a 5-1 win. If Doc was back, hope was back.

Problem was, Bobby Ojeda, Rick Aguilera and David Cone were all out with injuries, and the Mets were vamping in the starting pitching department two out of every five games. That’s where an available right arm idling in Connecticut came into play. Four days before their reigning ace’s 1987 debut, Jack Lang broke a story in the Daily News that the Mets were in touch with their old ace. “Old” may have been the operative phrase, for even if Tom Seaver was and would always be The Franchise — and even if he had pitched effectively for the Red Sox in 1986 before a knee ailment eliminated him from their postseason rotation (and saved Mets fans from at least a sliver of emotional tug of war) — he was still a 42-year-old pitcher who hadn’t pitched in nearly nine months.

News you might figure would have been greeted with more huzzahs. Individual Mets from the club’s 1980s imperial phase were never shy about issuing opinions. Some players were conditionally supportive of the possible signing. “He may not be the Tom Seaver of old,” Wally Backman allowed, “but he knows how to pitch. If he’s healthy, he could help us.” Keith Hernandez countered, “We need immediate help. I don’t know how long it’d take him to get ready, and we need help right now.” Mex guessed Seaver would require a month to prepare, or roughly what the much younger Gooden spent tuning up. Gary Carter caught Seaver in January as part of a video shoot. “I can tell you that he could pitch in the majors today if he throws the way he did in the video,” Kid said. “He could give us a boost.” As an added endorsement, Carter noted, “Mickey Mantle took a few cuts against him and couldn’t hit him.” Mantle, however, hadn’t batted for real since 1968.

Less willing to see the Seaver glass as half-full was Lenny Dykstra. “I know we need another pitcher,” Nails assessed, “but I’m not sure he’s the one we need.” To Rafael Santana, one inactive pitcher profiled pretty much like another. “Maybe we should sign Pedro Borbon,” the shortstop said, referring to the Reds reliever of the ’70s. “He hasn’t pitched in six years.” One Met unwilling to put his name to his words threw this knockdown pitch at the prospective reunion: “He wasn’t the most popular guy in the clubhouse when he was here in ’83. I guess this shows we’re really desperate.”

Three years after the passing of the greatest Met who ever lived, the barely audible huzzahs for Seaver, let alone the thumbs-down reaction to the whole idea, come across as blasphemy. But in the moment, a pitcher who turned 42 the previous November and hadn’t fired a pitch in competition since he was 41 — never mind that this was 41 being talked about — may not have appeared an obvious plug to fill a gaping hole. Then again, he was Tom Seaver. He was 41 and all that implied. “Desperate times call for desperate measures,” Phil Pepe wrote in the News, labeling Tom Terrific “chicken soup for the Mets: he may not help, but he couldn’t hurt.”

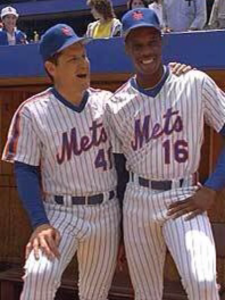

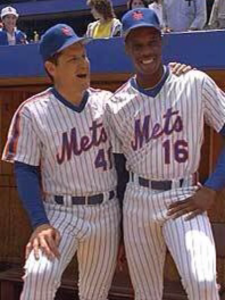

Tom Seaver didn’t have to be the Tom Seaver of 1969 in 1987. Being better than the Tom Edens of 1987 (a fill-in starter who wasn’t closing the rotational gap) would suffice. As chicken soup for the staff, Seaver’s presence loomed as mmm, mmm, good enough. Thus, Seaver was back at Shea the morning after the night Gooden was back at Shea, and maybe the world was as it was supposed to be, the only two Met Cy Young winners to date aligning like the stars they were in our galaxy. GM Frank Cashen was clear there was “no sentiment involved” in the move, but the Bow Tie’s business implored him to be all business. Of course there was sentiment involved. Tom Seaver was no Pedro Borbon, no standard-issue retread. Doc Gooden was only 22, but he understood and respected the bona fides of his new teammate.

“Being on the same club with Tom Seaver is a tremendous thrill. It’s going to be great having him around. I’m sure he’s going to be a big help. I grew up following his career, him and other guys like Nolan Ryan, J.R. Richard and Steve Carlton — all the power pitchers. I was a power pitcher in high school so, naturally, I followed them. It’s going to mean a great deal knowing you got him behind you. I look forward to getting to know him better.”

Doc did everything but quote from Hello, Dolly!. That flourish was left to Bob Murphy, who told Tom on the pregame show, “It’s nice to have you back where you belong.” In the audio clip that runs about ten minutes, you can hear the friendship between Seaver and Murphy, two avatars of everything beautiful about Mets baseball. In the moment, the news is the story. All these decades later, we can savor the interaction as a precious meeting of Met icons.

You can also hear…

• the “Let’s Do It Again!” theme that scored Mets baseball in 1987;

• a reminder that we were listening to “Sportsradio 1050 WHN,” the country station positioning itself to radically alter its format and its medium a few weeks hence;

• a smidge of Howie Rose not yet losing patience with the kind of call that a rabid (and later reformed) WFAN listener would not blame him for growing sick of in the years to come;

• rolfing talk, with invocations of Craig Swan and Tim Leary;

• Seaver acknowledging “I’ve been on vacation for seven months” and balancing his contentment with life after baseball with the fact that “I love to pitch”;

• Tom, still using the third-person to refer to the Mets, saying “these guys have a really good ballclub” and “they would love to repeat,” and you realize nobody has been able to use the second sentiment to express the Mets’ goal since that season;

• Murph shifting from referring to Seaver in the third person to talking to Seaver in the second person, a subtle pivot from addressing the audience to addressing his interview subject, but with Bob doing it, it’s so wonderfully familiar and graceful;

• that though he didn’t necessarily miss the routine of baseball, what really “got some juices flowing” for Seaver was playing catch, which may not sound like much, unless you’ve heard or read Bill Simmons tell the story of how fate led him, as a teenager, to be involved in one of those games of catch;

• Tom’s evergreen pitching philosophy: “Fastball, curveball, slider and changeup, high and tight, low and away, don’t throw ’em down the middle and don’t walk ’em — some things about pitching never change”;

• an estimate that in a normal Spring Training, Tom would need three starts to get up to five innings, though he would need longer to produce five “good” innings;

• a timetable that would have Tom throwing as soon as he’s done talking to Bob and pitching for the Mets in their visit to Tidewater later in the week;

• Tom’s answer of “I’m gonna have to work real hard on that” to Murph’s gentle nudge that after three years where the DH rule was installed, “you’ll have to start working on your hitting again”;

• Bob reiterating the target date that was floated for Seaver’s return during Tom’s press conference that morning: “around June the Twentieth, he’ll be back into action in the National League,” a lovely if distant echo of the Mets’ reason for being, namely the void New York fans felt once the Giants and Dodgers left town;

• Tom Seaver’s honorarium for visiting with Bob Murphy will be gift certificates to Crazy Eddie…and if you haven’t heard it in a while, don’t deprive yourself of the sound of Bob Murphy informing everybody that “Crazy Eddie, his prices are insane”;

• and that, per Murph, all this is going on amid “a beautiful Saturday afternoon in New York”

I can attest to the last bullet point, if we make like the local football teams and include New Jersey in New York. I listened to this interview when it first aired over Sportsradio 1050 WHN, while pulling out of the parking lot of the Marriott in Saddle Brook, the site of my first overnight getaway with my girlfriend of then 26 days, if we’re counting back to May 11, 1987, the night she and I met. Our first actual date — at Shea Stadium (where else?) — was 22 days earlier, May 15. There’s a brick outside Citi Field inscribed with the pertinent details of that outing, so maybe that’s when the relationship picked up its requisite steam. By June 4, Stephanie and I were already talking about marriage as a done deal. It seemed most appropriate to cross state lines together on June 5, with Doc pitching on the car radio, and wake up June 6 to the news that Tom really was coming home.

When stars were briefly aligned. Our 32nd wedding anniversary, by the way, was just over a week ago. As I said, that detail was a done deal by that first week in June of 1987. We had our little trip to Jersey, we crossed the George Washington Bridge back into Manhattan, and the Mets would go on to defeat the Pirates once more. A beautiful Saturday afternoon in New York, indeed.

Tom’s homecoming didn’t quite pan out. The exhibition game in Tidewater on June 11 wasn’t encouraging, nor were the simulated games Tom threw to Met reserves. Once he was lit up by the likes of Barry Lyons, Seaver knew he didn’t have any competitive pitches left in his right arm and wasn’t going to be able to help the Mets attempt to repeat. “I was looking forward to writing his name in the lineup,” Davey Johnson said as the comeback attempt concluded without the desired results. On June 22, the Mets held a press conference at Shea to announce Tom Seaver’s retirement, an occasion Cashen termed simultaneously sad for the ending and happy for the setting. Bench coach Bud Harrelson, Tom’s roommate on the road all those years, reasoned that even if Tom wouldn’t be going back to the mound, at least he was stepping aside in “our uniform”. No offense to Crazy Eddie, but that represented the greatest gift inherent within Seaver 3.0.

Not as epic as a Luis Guillorme at-bat in Port St. Lucie or a Bob Murphy interview of Tom Seaver in 1987, but perfectly enjoyable: this latest episode of National League town.

by Greg Prince on 15 November 2023 1:19 pm Whether as a season ticket perk, a stop on a tour or an element of community outreach, the Mets’ press conference space is sometimes occupied by activities other than Mets’ press conferences. Once in a while, when I’m at Citi Field with a media credential and I’m a bit early, I’ll step into the room usually used for official communications and glimpse something other than a Mets press conference in progress. The setting is familiar, the faces aren’t.

Watching on TV Tuesday, I had that same sensation. The curtain of dancing logos was hung as if to appear organic; the dais was in place (albeit in the Piazza 31 Club, because the Shannon Forde Room downstairs is ensnared in ballpark renovations); and the mics were amplifying sound. But in front of the occupied rows of chairs, there were a couple of people who, when the 2023 season ended, were essentially strangers to our baseball-consuming experience. On Tuesday, they were seated as if they belonged at the head of that room. They were talking authoritatively about the team to which we are emotionally attached. They were necessarily commanding the attention of a dutifully recording audience. I was watching because I felt I had to watch, regardless that I couldn’t shake my overriding thought of, “Who the hell are these guys and why are they talking about my Mets as if they have something to do with them?”

“Who are these guys?” is a question a Mets fan would have found challenging to answer not too many months ago. Those strangers/these guys have a topline grip on the fate of our Mets fan happiness for the foreseeable future. Not that anybody can foresee the future.

David Stearns and Carlos Mendoza can’t be called strangers anymore. They are, respectively, the president of baseball operations and manager of the New York Mets. We made the camera-filtered acquaintance of Stearns at the outset of October, and we’ve been introduced to Mendoza in mid-November. The Met months we care most about are February and March somewhat, April through September intensely, and the parts of October and November that don’t take place in a press conference room if we’re lucky. We were a little lucky in 2022, not at all in 2023.

So we meet Stearns and we meet Mendoza, and they tell us how excited they are to be among us and that they’re going to do their best for us, and it is up to us to trust them and believe in them. Why wouldn’t we? Because we’ve had so many versions of these press conferences in recent memory? Because October and November at Citi Field being used for something other than press conferences has been a rare and fleeting experience? Because we’re practiced cynics hardened against an onslaught of platitudes, especially those extolling changes in the prevailing Mets culture?

All of the above. But let’s trust and believe in David Stearns and let’s trust and believe in Carlos Mendoza, anyway. They’re erstwhile strangers now. They’re the guys we’ll get used to seeing with the curtain behind them, the microphone in front of them, the weight of the franchise on their shoulders. It behooves us to be David Stearns fans and Carlos Mendoza fans. We’re New York Mets fans. For the unseeable, foreseeable future, they and we are in this thing together.

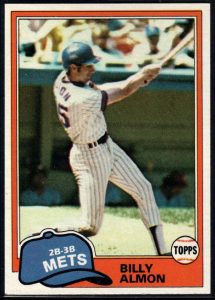

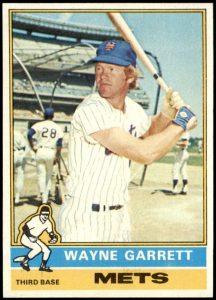

by Greg Prince on 10 November 2023 4:37 pm Welcome back to Faith and Fear in Flushing’s recently dormant series 3B-OF/OF-3B, an attempt to understand why the New York Mets have spent so much of their (and our) lives trying to fit guys who play one position well at a position where they inevitably less well. Or, if you care to be sanguine about it, we endeavor to celebrate the versatility of the now 83 players who played both third base and the outfield for the Mets.

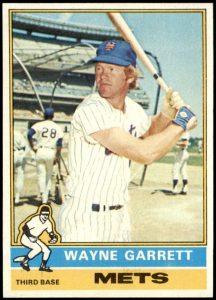

Wayne Garrett was not one of those players. He was versatile enough, with intervals at second (where he made his major league debut in April of 1969) and short (he was the “6” in the famous 7-6-2 putout of Richie Zisk at home plate the night the Mets definitively thwarted the Pirates in September of 1973), but what he did he did in the infield. Yet we can’t talk about the 3B-OF/OF-3B dizziness that afflicted the Mets in the years that followed Garrett’s trade to Montreal without Garrett, because Garrett leaving seemed to open the floodgates to a whole new multipositional matrix. No fewer than eight Mets joined the ranks of third basemen-outfielders in the next seven seasons. You might say that Wayne Garrett, on his way out of town, had ushered us into the octagon.

The self-perpetuating mythology that the Mets of their first two decades could never find a permanent third baseman tended to ignore the contributions of one Wayne “Red” Garrett, probably because the Mets themselves tended to ignore the contributions of one Wayne “Red” Garrett. Between May 4, 1969, and July 16, 1976, the New York Mets played 1,202 games. Wayne played third base in 711 of them, a clear majority. This includes 1971, when the redhead was serving his country until July in the Army Reserve as part of the last generation of ballplayers who had to fulfill such commitments. When he was available to play across his eight seasons as a Met, Garrett played the lion’s share of third, at first sharing time as a rookie with veteran and poet laureate Ed Charles, then threading appearances around imported answers Joe Foy, Bob Aspromonte, Jim Fregosi and Joe Torre.

“They tried to get a third baseman every year I was there,” Garrett reflected a couple of months after he was no longer a Shea Stadium staple. “I always felt if I didn’t have a good year, I wouldn’t be back.”

Wayne had the longevity. When he played his 711th game at third for the Mets, Wayne held the franchise record by several miles (Charles was second at 247). To this day, Wayne Garrett is the only Met to have played third base for the club in more than one World Series. His longevity in the position in his time seeped beyond the borders of Shea Stadium. Every year from ’69 to ’76. Garrett ranked among the Top 20 third basemen in the National League in terms of games played. Only two other NL third-sackers maintained that kind of presence across those eight seasons: Doug Rader and Richie Hebner.

Tony Perez was switched from third base to first base after the 1971 season and never played on the left side of the diamond again. Ron Santo was traded from the Cubs to the White Sox following the 1973 season and retired after one year on the South Side. They were the cream of the NL’s third base crop when Wayne broke in. Their accomplishments might have won them the status of immortality eventually, with each man today enshrined in the Hall of Fame, but they weren’t immune to being told they were no longer their team’s third baseman. Wayne Garrett didn’t reside in their echelon. He was forever being told he wasn’t going to be the Mets’ third baseman. Hence, the importation of Foy in 1970, Aspromonte in 1971, Fregosi in 1972 and Torre in 1975.

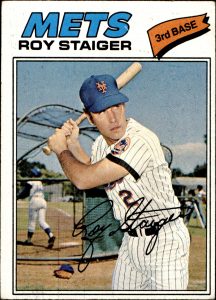

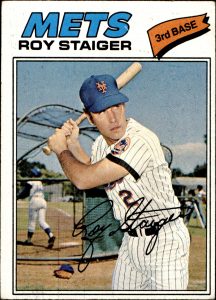

In 1976, the message finally became official. On Friday night July 16 at Shea versus Houston, Wayne started at third, made two putouts and two assists, and went 0-for-2 before giving way to pinch-hitter Roy Staiger. Talk about symbolism. Staiger had staked out his Third Baseman of the Future territory with his big year at Tidewater in 1975. Roy and Wayne more or less shared the position for three months of ’76, with one or the other getting swaths of playing time at third, and Wayne filling in at second for a ten-day stretch spanning May and June. Perhaps to indicate the shift from Garrett, 28, to Staiger, 25, was incomplete, the start at third base on Saturday afternoon July 17 went to utilityman Mike Phillips. Garrett pinch-hit in that game, for starting shortstop Buddy Harrelson, after which Staiger entered for third base defense, moving Phillips over to short. Elsewhere in the box score of this all-too-typical 1-0 loss for Tom Seaver (he struck out eleven, giving up only a barely fair, barely gone first-inning homer to Cesar Cedeño, while Met bats provided no support for their ace), we find Dave Kingman in right, Jerry Grote behind the plate and Joe Torre having pinch-hit for Seaver in the eighth.

Jerry Grote was the Mets’ 28th third baseman.

Wayne Garrett was the Mets’ 40th third baseman

Joe Torre was the Mets’ 48th third baseman.

Roy Staiger was the Mets’ 50th third baseman.

Dave Kingman was the Mets’ 51st third baseman.

Mike Phillips was the Mets’ 52nd third baseman.

As of July 17, 1976, 52 different Mets had played third base since the club’s 1962 founding. Six of them were in this game.

Two days later, Wayne made his final appearance as a Met, striking out as a pinch-hitter for Ken Sanders on the night Kingman — in left — hurt his thumb diving for a fly ball off the bat of Atlanta’s Phil Niekro, not only not making the catch, but short-circuiting his pursuit of the National League home run title, perhaps the National League home run record. Dave had 32. Hack Wilson had 56 in 1930. The chase of history went out the window, as did Kingman’s chance to become the first Met to lead the NL in homers. With Sky King confined to what was then called the disabled list until September, another third baseman, Mike Schmidt, caught and passed him. Compared to losing their only true power source, the trade that went through the next day was relatively small potatoes. For a franchise that was in only its fifteenth season, however, it represented a milestone, something beyond the same old same old…even if there was an element of déjà vu all over again underpinning it.

The Mets were sending their all-time third baseman to Montreal. Garrett and center fielder Del Unser became Expos so Pepe Mangual and Jim Dwyer could become Mets. Newsday’s headline: “Revolving Door Ejects Garrett,” with Malcolm Moran reviving and slightly revising a lede that could have served any reporter covering this team since 1962. “For 15 years they have come and gone,” he wrote, “each one staying for a while to occupy third base at the Polo Grounds and Shea Stadium.” As much as Garrett was the exception to the rule, the rule got him in the end. No Mets third baseman was safe.

DiamondVision was six years from existing, which was just as well, since Mets management in 1976 didn’t seem of a mind to produce a “THANKS WAYNE!” video. Manager Joe Frazier, trying not to get tossed from the revolving door himself as his team floundered double-digits from first place, referred to the veterans the Mets were jettisoning, each of whom carried a batting average in the .220s, as “deadwood,” adding that he considered his roster “pretty old. We’re stale in a few positions.” GM Joe McDonald was a little more diplomatic regarding the departed, choosing to talk up the youth and speed that would define the Mets’ lineup the rest of the way. So many times the Mets sought to supplant Wayne Garrett by bringing in somebody older. Now they did it with the homegrown Staiger, someone three years younger.

“I think Roy deserves a shot,” McDonald reasoned, “and as long as Garrett was there, the temptation was to play him.” Garrett, content to be wanted by the Expos as something other than a bad habit, didn’t apologize for his perennial resilience or continual attractiveness:

“Over here, they’ve always had the problems of third base, third base, third base. Now I’m out of the picture. Let ’em go ahead and get their third baseman. They’ve been trying to get one for eight years.”

They’d keep trying.

To helpfully warn us what would lie ahead between 1977 and 1983, Red did what Old Friends™ do. On September 29, 1976, in his first series back at Shea, Garrett crushed a grand slam off Tom Seaver to lead the Expos to a 7-2 win. It was Wayne’s first grand slam at any level. “I never hit one in high school or Little League or Babe Ruth or anything,” he said, and he couldn’t have been happier to have saved it for McDonald and Frazier. “It showed the management here about the trade.” As if Pepe Mangual (.186) and Jim Dwyer (.154) hadn’t shown them enough.

Seaver entered the night leading the league in ERA, but his old third baseman put an end to his chance to add another of those titles to his already brimming résumé. Tom would have to settle for finishing third in the category, just like the Mets in the standings, whose late surge to 86 wins nonetheless left them far from Schmidt’s first-place Phillies. Since 1969, when Tom and Wayne and all the Mets captured the world championship as well as the imagination of North America, the Mets expected better of themselves, even if we in the stands and watching from home kind of got used to them winding up stuck in the middle of the NL East pack. The 86-76 record looked better than it felt.

“It’s been that kind of year,” Seaver said without any cheer in evidence.

When it came to the Mets and “that kind of year,” Tom and we had no idea what awaited over the horizon.

***It’s May of 1977, and starting at third base for the New York Mets is Jerry Grote. That wasn’t the plan when Wayne Garrett was traded to clear a path for Roy Staiger. Not even as Staiger finished 1976 batting .158 was anybody thinking the rookie would be pushed aside by the second month of what was supposed to be his second full year in the majors. Roy, whose latter-day defensive metrics indicate he was one of the better fielding third basemen in the NL in ’76, was the Mets’ Opening Day third baseman in April ’77, homering in the team’s second game. A lingering groin muscle pull from Spring Training sidelined him for a few days, but he was back out at third soon enough. National League pitching began getting the best of him again, with his average dropping below .200.

Roy had the promise. When he did get on base, trouble awaited. After reaching on an error in the fourth inning at Candlestick Park on May 7, Roy came around to score from second on a single. Staiger had to slide to make it home. In doing so, his left hand was cut by Giants catcher Marc Hill’s left spike. Roy left the game and found his cut hand not improving, with swelling still a factor a week later. He’d be out ten days in all, during which time Grote — acknowledged over the previous decade as the best defensive catcher this side of Johnny Bench (and even Bench admitted he’d be the one to start working out as a third baseman if the two played on the same team) — exchanged his mitt for a glove and started eight of nine games at third base.

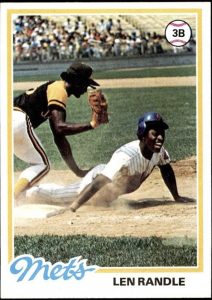

It wasn’t unprecedented. Jerry had played third twice for the Mets in 1966, three times in 1972 and twice more in 1973 (along with a turn in the outfield in ’72) — plus he had been Wayne Garrett’s roommate on road trips and might have picked up a couple of pointers along the way. Yet it was unanticipated. Then again, in 1977, anything seemed to go, especially the Mets’ chances of contending. They were off to a 10-18 start, their worst in ten years, when Jack Lang noted in the Daily News that Grote was serving as “the Mets’ 50th third baseman this season”. A little hyperbole was permissible, as the club had already cycled through Staiger, Phillips, Torre, the previous September’s callup journeyman Leo Foster and the lately acquired Lenny Randle at third. Grote made it six in twenty-seven games. Frazier, leaning on a 34-year-old catcher who had almost retired during the preceding offseason because of chronic back pain — Topps didn’t even bother to issue a card on his behalf in its ’77 set — to refamiliarize himself with terrain he hadn’t defended in four years, acknowledged, “We need Roy’s glove.”

He tried his luck with Jerry’s. “Grote,” Lang wrote, “doesn’t have great range, but he does have good hands and has played the bag before.” Still, an older catcher playing third base is a an older catcher playing third base. At Shea against the Giants, there was a bunt Jerry couldn’t handle, and versus the Dodgers, there was a Dusty Baker line drive beyond his leaping reach that earned back page prominence in the News, with an arrow printed by the ball to imply Grote may have been out of his depth. Lang’s more charitable assessment was, “The Mets were not hurt during Staiger’s absence,” judging Grote as having “filled in quite capably. He was as much of a whiz with the glove there as he is behind the plate,” where he was being eased out to make room for young gun John Stearns. Stearns was the Opening Day catcher and held down the position almost without pause into mid-May.

John had been waiting for his break since backing up Grote throughout his rookie year of 1975. “He’s a fiery guy, a real hustler,” his first Met manager Yogi Berra said of his prized prospect backstop. “I hate to sit him. I want him to play every day and if Grote gets hurt, he’s only one day away.” Patience wasn’t exactly the kid’s calling card. At the end of his freshman season, Stearns told Journal News reporter Al Mari that he was ready to ask for a trade if he wasn’t going to catch regularly. “Call it bad management, but I never got a chance here,” he said that September. “You can’t play every ten days and stay sharp. I know I can do the job up here.” In 1976, Stearns, still a Met, accepted the wisdom of having that chance at Tidewater, opting to get better at Triple-A rather than sit in frustration in New York. In 1977, he was back to stay at Shea and on his way to his first All-Star Game, minting his status as catcher of the present.

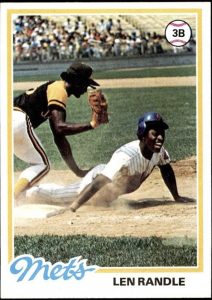

Another Met gaining a measure of satisfaction in a May that wasn’t otherwise merry was the new guy in town, Randle. Lenny was the avatar of the unanticipated. During Spring Training, he was a Texas Ranger, as he had been since the Rangers moved to Arlington from Washington in 1972. But the incumbent second baseman, 29, was falling victim to the same dynamic that saw Grote being nudged aside for Stearns. In the Rangers’ case, it was Bump Wills, who graced the cover of Sports Illustrated as the head of the class of NEW FACES OF ’77. It wasn’t a smooth transition in Randle’s view, and tensions rose between him and manager Frank Lucchesi. Lucchesi called Randle a punk for complaining. Randle fought back, literally, punching out his manager. Texas suspended the player.

Noticing there was a proven major leaguer in his prime as available as could be, and satisfied the Lucchesi incident was an aberration, the Mets took a flyer on Randle in late April and made him their new face of ’77. Frazier may have been in the same profession as Lucchesi, but was of a different mindset where Lenny was concerned. “I wish I had four or five more just like him,” Joe said, pleased with the erstwhile Ranger’s early Met production. The reception among teammates was almost universally positive. “Phenomenal,” Jon Matlack called him. “He’s got a magic wand. he’s great to have on the ballclub.” Ed Kranepool observed, “He’s playing great baseball. He hustles, he works hard. He’s not a problem on the club.”

One voice missing from the choir of hosannas was that of the Mets’ own incumbent second baseman, Felix Millan. Randle was versatile, but second base was where Frazier inserted him, which mystified Felix, who had served the Mets steadily since 1973. “Randle plays third and the outfield, and we have a catcher playing third base,” Millan said. “Why is he playing second base? Nobody’s told me anything. They just gave Randle my job. If they don’t want me here, they can trade me. I know I can still play every day for somebody.”

Millan was hardly the only Met looking for an exit from Shea Stadium as May was nearing June in 1977, but before the month was out, he no longer had to worry about a catcher playing third base. Staiger was healed and given his job back. Alas, the Mets continued to lose, and somebody was going to be given a ticket out of town. Not surprisingly, it was the manager. Joe Frazier was fired on May 31.

“I was ready to get out from under,” Frazier said of his 15-30 club. “It was driving me up a tree.” Ready to take on the same daunting oak of a challenge of steering the Mets out of last place was Joe Torre, initially hired as a player-manager (a designation that lapsed after a few weeks). The Mets had never had one of those before, but they also never had so much obvious dissension roiling their clubhouse. Millan wanted out. Matlack wanted out. Kingman was more unhappy than usual. And, not incidentally, Seaver’s ongoing conflict with M. Donald Grant was its own prime time drama.

“If Joe can do better with the team,” Frazier said, “more power to him, but I honestly didn’t see anything encouraging on the outskirts.”

The new Joe did one thing upon his taking over. He declared Lenny Randle would be his everyday leadoff hitter and third baseman (with Millan resuming everyday duty at second). Roy Staiger’s return from his hand injury, during which he batted .308 in eleven games, did not win him any long-term goodwill from the new manager, who knew a little something about playing third base. He also knew Randle, whose first few Met days included a couple of reps in left, was the hottest player Frazier bequeathed him, with an average that soared above .350. Staiger, for whom the Marc Hill cut was the deepest, was assigned to Tidewater for most of the rest of the season; come December, he was traded to the Bronx for Sergio Ferrer. Except for four games as a Yankee in 1979, Roy spent three years marooned in Triple-A, and was then through as a major leaguer. While he hadn’t made a great case for himself as the Met solution at third base, his tenure turned truncated once he experienced that injury to his hand after he slid home in San Francisco.

The batter who drove him in and ultimately toward dispensability? Lenny Randle.

***For about a week, Joe Torre definitely did better than Joe Frazier with the team. The Mets responded to their old peer and new leader, winning seven of eight. It was Honeymoon in Flushing time, but honeymoons last only so long, and the Mets’ 1977 season was trudging onward no matter which Joe was running the show, stuck in sixth place for the duration. Whatever respect and affection Seaver and Kingman had for the new skipper did not extend to the chairman of the board. Both stars wanted out, and both men were accommodated by a tone-deaf front office that sent both packing. Kingman, slumping but still the Mets’ only bona fide slugger, was sent to San Diego. Seaver, merely The Franchise, was traded to Cincinnati. The season, already doomed, was now dead. The era in which the Mets finished above .500 almost annually and fancied themselves de facto contenders heading into every April was just as gone. Those frustrating third-place finishes of the early and mid-1970s were about to start looking impossibly aspirational.

Seaver and Kingman wouldn’t be the last stalwarts of the previous era to walk out the door in the months ahead. Felix Millan’s hold on second base ended with a body slam from baserunner Ed Ott in Pittsburgh in August. The next time he played ball, it would be in Japan (for two years sharing a league with post-Expo Wayne Garrett). Jerry Grote was swapped to the Dodgers before September, in time to make L.A.’s postseason roster. Jon Matlack would find his trade request granted in December when he was dispatched to Texas in a four-team deal that also turned 1973 holdover John Milner into a Pirate. Before 1978 got underway, one more extremely familiar face was missing, with shortstop Bud Harrelson — a Met so long he was probably hiding somewhere within the club’s skyline logo — traded in Spring Training to the Phillies.

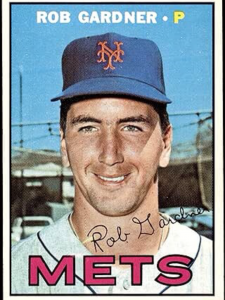

Before any of that happened, there was the matter of welcoming to the Mets the six players acquired for their two icons on June 15, 1977, along with another player exchanged for one of the Mets’ lesser lights. Seaver’s bounty was a starting pitcher, Pat Zachry (1976 co-Rookie of the Year in the NL); two minor league outfielders, Steve Henderson (who was immediately promoted to the majors as a Met) and Dan Norman (who would make his debut in September); and a glove-first infielder who was never going to crack the starting lineup of the Big Red Machine, Doug Flynn. Kingman wrought a reliever, Paul Siebert, and a veteran utility guy whose upward mobility in the game was years earlier undermined by a gruesome outfield injury, Bobby Valentine. That third deal, the one not dominating front and back pages, saw Mike Phillips go to St. Louis for a former Red, Joel Youngblood.

If you’re scoring at home, Flynn, Valentine and Youngblood all arrived wearing various labels of versatility, and each would play some third base for the Mets in 1977, elevating the season’s total to nine Mets on third, or the most in any year since 1967…which also happened to have been the last time the Mets finished last before 1977. Their hideous 64-98 mark represented a dropoff of 22 wins from 1976, a year-over-year plunge that would stand as the worst in Mets history until the Mets of 2023 stumbled 26 games off their 2022 pace. With so many of their veterans gone or going, the Mets tried to sell themselves to an increasingly indifferent public as an agglomeration of promising youth. “Bring your kids to see our kids!” newspaper ads suggested. Four of the of the Mets’ kids posing — Flynn, Henderson, Zachry and Youngblood (alongside Stearns and Lee Mazzilli) — were June newcomers. Crowds failed to materialize in response. Shea Stadium attendance set a new low in 1977.

Lenny had it all. Ironically, the baseball team so often cited for its revolving door at third base featured as its best player in its worst year in a decade its third baseman. Not that Lenny Randle was all that interested in the irony. “I’m not into the history of the Mets,” he advised. “I know they had a guy named Joe Foy and Ed Charles there, but that’s about all.” Third Baseman No. 54 concluded his first season in Queens batting .304 in 136 games; sealing two walkoff wins with that magic wand Matlack admired; stealing 33 bases to establish a new club record; withstanding the weirdness of being at the plate as darkness descended over Shea Stadium amidst the July 13 New York City blackout (“I thought to myself, ‘This is my last at-bat. God is coming to get me.’”); and answering, at last with authority, the question of “Who’s on Third?” Randle was delighted to claim the spot as his own. “I’d like to play here forever,” Lenny said toward the end of a season that few remaining Mets fans wished would go on any longer.

What Randle really adored was his position, especially that it was his. Versatility may appeal to managers and general managers, but as a player who shifted among second, third and the outfield in Texas, “I never knew where I’d be,” he explained. “You take ground balls for infield practice and fly balls for the outfield and when the game starts, you’re so tired you’re lucky if you have seven innings in you. I love third base. I’m doing the best I can to master it.”

In a year when the Mets couldn’t have been less popular, Lenny was the Met most easily embraced. “You can’t help but love the fans in New York,” Randle said as he grew accustomed to his surroundings. “They pump you up. I feel I owe the fans my best as an entertainer. I don’t cheat them.” His second Met manager was just as crazy about him as his first. “Randle has great instincts to get to the ball,” Torre said in September. “He catches line drives, throws from his knees, he’s a scrapper. He has been all year. As of now, there is nobody on this team than can do the things Lenny can. He’s aggressive offensively and makes great plays defensively.” If not much else seemed bright about 1977, at least we could count on the productive and beloved Lenny Randle at third base, presumably for years to come.

Lenny Randle lasted one more year as a Met. It didn’t go as well as it did in 1977. Before 1978 was over, four more Mets who hadn’t yet taken a turn there would get a crack at the hot corner Randle would wind up vacating before Opening Day 1979. The revolving door was destined to spin quite a bit into the decade ahead and sputter in circles before the Mets would return to contention. And the mixing and matching of third basemen and outfielders — encompassing miscasting, reluctance, dismissiveness and a couple more catchers — was just getting going.

Yet again.

THE METS OF-3B/3B-OF CLUB

Turn and Face the Strange (1976-1977)

21. Lenny Randle

Mets LF Debut: April 30, 1977

Mets 3B Debut: May 8, 1977

22. Joel Youngblood

Mets 3B Debut: June 24, 1977

Mets LF Debut: June 27, 1977

PREVIOUS INSTALLMENTS OF 3B-OF/OF-3B

Chapter 1: 1962

Chapter 2: 1963-1969

Chapter 3: C-3B-OF

Chapter 4: 1970-1975

by Greg Prince on 7 November 2023 5:51 am When I first heard of bright, young Yankees bench coach Carlos Mendoza a few years ago, I was disappointed to think that our September 1997 callup outfielder, the one who broke up Dustin Hermanson’s no-hit bid in what became known within certain circles of the Metsnoscenti as The Carl Everett Game with his first major league hit, had gone wayward in life. Aw, a Yankee? Then again, we couldn’t be responsible for what a Met of 15 games did with his post-playing career more than 20 years later, especially once he was exposed in the ensuing offseason’s expansion draft and was selected by the Tampa Bay Devil Rays.

Then I looked into Yankees bench coach Carlos Mendoza a tiny bit further and realized he’s a different Carlos Mendoza. Our Carlos Mendoza from 26 years ago was born in November 1974. Their Carlos Mendoza from these days was born in November 1979. The November 1979 Carlos Mendoza would have had to have been 17 to have played for the 1997 New York Mets. Ed Kranepool, born in November 1944, was and remains the only 17-year-old to have ever played for any New York Mets.

That was the tipoff that the Carlos Mendoza I remembered wasn’t the Carlos Mendoza who was getting written about as a bright, young managerial candidate. As a fan of a franchise that has sorted through pairs of Bob Millers, Bob Johnsons and Bobby Joneses, to name one trio of duos (the Mike Marshalls, Pedro Martinezes and Chris Youngs amount to another three), it was easy enough to discern once the facts were examined.

For a franchise that has sorted through a surfeit of bright, young managerial candidates and actually appointed a few of them manager in the past half-dozen years, definitive and useful facts about those types of fellas tend to be elusive early. The Carlos Mendoza from the Yankees is now, by all accounts except official, the manager of the New York Mets, following in the footsteps of previously anointed bright, young managerial candidates about whom we knew only so much, which is to say nothing much, as potential managers. It’s probably no more relevant to invoke their names than it is the Carlos Mendoza from the 1997 Mets, but we don’t have a lot of facts to tell us anything else.

Hence, we will think of Mickey Callaway, who was considered hot stuff when the Mets grabbed him in October 2017; and Carlos Beltran, who was considered an intriguing choice when the Mets grabbed him in November 2019; and Luis Rojas, who was considered a promising Plan B worthy of the shot the Mets were giving him in January 2020. We might also think of Buck Showalter, who succeeded all of them in what amounted to no time (hired by the Mets, December 2021) at all because none among Callaway, Beltran or Rojas lasted very long if at all. Then again, neither did the massively experienced Showalter (honored as NL Manager of the Year, November 2022; dismissed as manager of the Mets, October 2023).

Here we are, well into this offseason’s The Mets Are Hiring Another New Manager story and we’ve barely talked about the new manager. Pending his introductory press conference in which he will be presented in the best of lights, what is there to talk about as of now other than he’s not the guy with the same name from 1997 and he’s not those guys who invited the same broad-strokes categorization from previous introductory press conferences? This Carlos Mendoza has never managed in the big leagues before? Neither had any first-time big league manager. Some succeeded in their first posting. Some would go on and find success at a later date in another place. Some weren’t what was hoped for when hired and never much panned out for anybody.

That frames Carlos Mendoza the New York Mets manager in even broader strokes. He could be anybody. But broad strokes are what we have, along with the endorsements he’s gotten about being bright and young and capable and confident and collegial and communicative and comfortable with computerized calculations. The next contemporary manager lauded in advance for his lone-wolf tendencies and disdain of data will be the first. If sliced bread isn’t the comp for what Carlos Mendoza will be hailed as the best thing since when he slips a Mets jersey over his shirt and tie, it will be an upset.

If Carlos Mendoza is the manager of the New York Mets for more than two seasons, it will be an aberration. That’s a calculation conducted not with a computer but from recent experience, all of it basically immaterial. Mendoza is not Callaway, Beltran or Rojas, just as he is not Showalter or 1997 Mendoza. He is an individual like any of us and, as long as he’s here and entrusted with what managers are entrusted, we have to trust him from the get-go. The get-go wears off once it gets going, and then the trust is conditional based on how the club he’s managing is playing, which probably won’t be fully reflective of how he’s managing, but he’s the manager and it’s easier for us to pin whatever’s going wrong on the manager. Or, perhaps, praise the manager for whatever’s going right. We do that, too, sometimes.

Carlos Mendoza is the manager of the New York Mets not only because his four predecessors entrusted with the role over the past six years don’t manage here anymore but, we infer from multiple reports, the manager the Mets really wanted, experienced Craig Counsell, chose to go elsewhere. That’s an inference. Counsell did go elsewhere, to Chicago from Milwaukee, but despite the on-paper sense it made that Counsell would follow David Stearns from the Brewers to the Mets, it’s possible Stearns and Steve Cohen concluded Mendoza was, when all factors were balanced, more the manager for them. Throughout this round of baseball teams interviewing managerial candidates, the buzz on Mendoza was consistently enthusiastic. Nobody not on the inside really knows what any of that means, but he must have been impressing more than one owner and one president of baseball operations. A career of managing in the minors and coaching in the majors that dates back to 2009 was leading somewhere, not just to hearty handshakes at the end of interviews. One of those interviews was bound to lead to a manager’s position.

Now he’s got it. What we’ve got we don’t know. We never do at the outset. If we’re still talking about Carlos Mendoza in the present tense more than two years hence, we’ll have an idea that we got something and someone good.

by Greg Prince on 6 November 2023 12:02 pm Whether it was out of quaint National League loyalty, appreciation for vanquishing the Phillies, or a fleeting fancy born of the whims of October, I was an Arizona Diamondbacks fan for five nights in the World Series, extending the quick hop I made aboard their slithering bandwagon during the NLCS. An interim fan, you might have called me. It didn’t work out in terms of a burst of vicarious championship satisfaction, but I was glad enough they were my team for a week or two (Brent Strom’s unbecoming September crankiness toward a Ford C. Frick Award nominee notwithstanding). They played good Diamondbacks baseball for as long as they could, moving runners over and the like; they were young and athletic, with a dash of experience to provide a little faith that they knew what they were doing. I didn’t know much about the Diamondbacks before the postseason. I was happy to make their acquaintance until, inevitably, I reverted to not much caring about them.

But it helps to have a rooting interest if you wish to be engaged by a Metless tournament. By Game Five of the World Series as Arizona tried to hang on for dear life, I believe I was rooting less for the D’Backs and more for more baseball. There was a ground ball as the middle innings were becoming the late innings that I really wanted to see reach the outfield but didn’t. C’mon, keep going. That grounder was carrying within its stitches my hope that the postseason would keep going, too. A month since they made their last out, I hadn’t missed the most recent edition of the Mets whatsoever, but I did feel a void when November baseball expired ahead of its allotted time frame.

The Texas Rangers dictated the World Series would last no more than five games, just enough to escalate onlooker interest by a tick. Our last two World Series of surpassing Metsian concern, in 2000 and 2015, teased us during fifth games that a sixth was somewhere between probable and possible, and if we could get a sixth game, who was to say there wouldn’t be a seventh? In 2000 and 2015, it was the Mets’ opposition answering that question. Winners of Game Five who enter said competition up three games to one too often write the history…though we didn’t mind that in 1969.

Despite cheering on their opposition like I meant it, I found nothing to dislike in the Rangers, an affable and talented bunch with a few faces fairly familiar to us lurking in the shadows. Goodness knows those who truly cared about them had waited long enough. An first-time/long-time world championship for a franchise — whether actually its first or the first most any living fan of that team has experienced — should be a cause for sportwide celebration, fans affiliated with the losing side excused if they’re not feeling the love. I watched a bit of the Rangers’ parade through the streets of Arlington. I imagine some in the crowd were simply big proponents of success and celebration, but you know plenty lining the sidewalks had waited what was, for them, forever. In the context of Texas Rangers baseball, transplanted from Washington in 1972 and proceeding ringlessly until Wednesday night, it had been forever.

Although I was on the side of the Diamondbacks, I could not see those shots of the Rangers dugout where their manager stood tall and not be all for Bruce Bochy. I rallied around the skipper during the Giants’ three World Series conquests in the previous decade and never developed any animus for the man despite his sending Madison Bumgarner to shut us out in the 2016 Wild Card Game. “Boch,” as they call him, just seems to have a feel for what needs to be done in any situation, whether it’s leaving a MadBum into finish a seventh game as he did versus Kansas City nine Series ago, or plucking an umpteenth reliever from the mound despite a seemingly unblowable lead and going to his closer to put the hammer down, which he did in Game Four this year when he replaced Will Smith with Jose Leclerc (Leclerc gave up a hit that made things a little closer, but in the end it worked). Every Ranger pointed to Boch’s calmness as the constant that got them through every bumpy moment in the season and postseason, and I could totally see it, especially when Rangers interviewed in the minutes after they eliminated their last obstacle and gained their first ring were cool and collected rather than shouting “WOOOOOOOOOOO!!!!!!!”. After Bochy retired from San Fran in 2019, I wondered if anybody in Flushing thought to give him a call on those several occasions we had an opening. He was apparently lurable and was damn well worth a feeler.

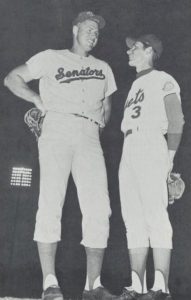

Eventually got a callup. Should’ve been called to manage the big club decades later. Of all within the Texas traveling party claiming Mets ties — idled pitchers Jacob deGrom and Max Scherzer, fill-in right fielder Travis Jankowski (whose performance helped his club remained calm following the injury to otherworldly Adolis Garcia), general manager Chris Young and pitching coach Mike Maddux — Bochy’s connection is both the most ancient and the least outwardly consequential. Bruce spent two years in the Mets organization, in 1981 and 1982, mostly with Tidewater. Perhaps he whispered something useful in the ear of a young Orosco or Darling that paid off long-term. Mostly, he was the guy who got written about in his first St. Petersburg Spring Training for having an oversized head and needing to tote his own batting helmet from team to team, where it would be painted whatever color would allow him to blend in. Bruce scored four runs as a Met. He has exactly that many World Series trophies to his credit now.

What a difference a manager makes. Or so we will allow ourselves to assume, considering San Francisco never celebrated a title until Bochy guided them to the promised land in 2010 (and 2012 and 2014), and North Texas wasn’t the capital of baseball until 2023. We will also wish to assume there’s something to this Leader of Men stuff because the Mets believe Carlos Mendoza is their next difference-maker, one who, if he’s as impactful as can be, will add his name to a very short list. Forty years ago at this time, the list of managers who had made all the difference to the Mets from a world championship standpoint contained only one name: Gil Hodges. That fall, fourteen years removed from the only Mets manager who had ever worked a miracle working that miracle, I don’t know if any of us imagined the newest fella hired to fill Gil’s old office was going to lead us toward a doubling of the names on that list.