The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 23 September 2023 1:24 pm Anyway, it’s turned cold and rainy here lately, but I like winter.

—Maya, in her answering machine message to Miles, at the end of Sideways

Pending iffy weather, the Mets are positioned to carve a statistical triptych of despair this afternoon in Philadelphia. Thursday night, they clinched a losing record for the season. Friday night, they were mathematically eliminated from their last remaining fraction of postseason contention. Their next milestone looms as the setting of the franchise record for most precipitous plunge from one year’s won-lost record to the next. Right now, at 71-83, they have a tie locked up, assured of being 22 games worse in 2023 than they were in 2022, when, for all our complaints about them through September and into October, they accumulated a mere 61 defeats. Our loss total at the moment relative to 101-61 in ’22 matches the decline from 1976 to 1977, the long-established standard for season-to-season Met falloff, one of those internal worsts it never occurred to me to look up until a season like this came along on the heels of a season like last season.

The Mets were nothing special in 1976, finishing 86-76 (though today that absolutely gets you into the National League playoffs). In 1977, the Mets avoided special like the plague, going 64-98, accelerating their ongoing descent into the abyss by trading Tom Seaver at the deadline. Forty-six years later, perhaps some analytically inclined junior executive in Flushing posited, “If we sent away one Hall of Fame pitcher in the middle of the season and we went to hell, imagine what would happen if we send away two…”

Gonna guess hardly a Mets fan alive decades from now will identify the days Max Scherzer and Justin Verlander were instructed to pack as the moment that signaled the end of childhood, and I don’t truly believe a 1978-style 2024 is on deck. Different times, different contexts. But 22+ losses worse is 22+ losses worse, although as much as I do remember about 1977, I don’t remember when exactly the 1977 Mets were mathematically eliminated. Being mired in last place in a pre-Wild Card world will take the edge off such details.

I almost forgot mathematical elimination had just happened to the 2023 Mets when the game that did them in, their 154th of a planned 162, went final. Watching a game on a streaming service on a tablet, some strange app’s pictures synced to familiar radio sound, will knock a person off-kilter, even a person who’s spent most of his waking hours monitoring an off-kilter team for 154 games for nearly six months. When the Mets didn’t take advantage of Brett Baty’s revival from imploded prospect to rising star — game-tying homer in the top of the ninth; game-saving defense in the bottom of the ninth — by not driving home their speediest ghost runner possible, Tim Locastro, in the top of the tenth, you figured the Phillies would find a way to end the whole affair quickly if not painlessly. How much one feels the sting of another 5-4 loss, this one on Alec Bohm plopping a single into short right, ensuring Philly apparition Trea Turner would motor in with the winning run, depends on how much feeling you have left in your Met epidermis with just over a week remaining in 2023.

I suppose it always hurts to lose in extra innings. I suppose it always hurts to lose in Philadelphia. I suppose it always hurts to see gumption like Baty’s go unrewarded in the course of an evening. I suppose Tylor Megill’s almost six innings of shutout ball flying over the left field fence, courtesy of one mighty blow off the bat of J.T. Realmuto, converting a 2-0 Mets lead over Old Friend™ Taijuan Walker into a 3-2 deficit, hurt from the standpoint of rooting a young pitcher along, but I honestly don’t know about the last one. Postgame chatter about the shame of Megill putting in almost six innings of spotless ball, only to have his valiant night besmirched by Realmuto, put me in mind of the night in 2013 when Dillon Gee carried a 1-0 shutout into the ninth in Atlanta, only to have Justin Upton single with one out and Freddie Freeman launch the game-winner/game-loser one batter later. Except Gee was trying to go nine, and it’s a national holiday when Megill can go six.

You’re lucky if you can feel anything from this team after 154 games and 83 losses, but the numbness was pierced when I realized, after clicking off the Friday night stream that, oh yeah, we were eliminated, weren’t we? This September’s Met discourse wasn’t infiltrated by one of those tragic numbers a fan tracks as a quixotic lunge for a postseason berth inevitably sputters. Rob Manfred would be disappointed to learn the 2023 Mets didn’t make as much as a ghost run at the playoffs.

Yet the finality suddenly hit me. We were done with eight games to go. We were done when there were seventy, eighty, ninety games to go, really, but math has a way of sealing the deal. To the televised postgame show, I said boo. I mean actually booed the TV. I booed Gary Apple. I booed Todd Zeile. I booed whatever inanimate object I could find. The Mets were pretty inanimate most of the year.

Stephanie stuck her head out of the upstairs bathroom where she was getting ready for bed. She inadvertently had the postgame show on the radio, me having helpfully tuned it to 880 for everybody’s listening convenience. I reported, with dark irony (as if it was worthy of a bulletin from an all-news station), that we wouldn’t be going to any playoff games this October. She is aware of the state of the Mets on a conceptual level — whether they’re good or not so good — but doesn’t check the standings multiple times a day. I wanted to confirm their current status aloud for somebody who wasn’t inanimate.

“I’m sorry, baby,” my wife replied from the top of the stairs. She really meant it, too. After all these years and all these mathematical eliminations, she understands. No need to calibrate for inevitability versus devastation.

The weekend we got engaged, which was exactly 34 years ago, I decided the best way to burnish our rite of coupling passage was by going to the Mets-Phillies game that Monday night. About 18,000 people joined us at Shea Stadium. The game story in one of the papers the next day referred to the lot of us as “entertainment-deprived”. Bobby Ojeda pitched against Pat Combs, nursing a 1-0 lead into the eighth. Tommy Herr played the role of J.T. Realmuto/Freddie Freeman on that occasion, belting the two-run homer that ensured a 2-1 ending and the ouster of the Mets from what was left of their semi-serious pursuit of the 1989 NL East title. It was Game 156 that night. There was no realistic chance the Mets were going to catch the first-place Cubs by then, but still. Mathematical elimination is mathematical elimination. Last out came and I just sat, which meant we both sat, which meant we had to put on speed to make our train, which isn’t something I make my wife of now nearly 32 years do if I can help it (the lady doesn’t like to be rushed). But Stephanie respected my Shea mourning ritual for the 1989 Mets that Monday night and did the same for the version I unfurled in our living room on a Friday night in 2023.

It felt really sad to realize definitively that the defending 1988 National League East champions would not be playing beyond their 162nd game. I can’t say it feels anything like that anymore vis-à-vis what the Mets accomplished in 2022. For a while in 2023, even as realization came early that These Mets weren’t likely going anywhere, a good inning or a good game would awaken the echoes of the year before, as if this team was still, in its soul, that team. The 1989 Mets were no longer the 1988 Mets, certainly not by September 25, yet, I decided, those Mets who remained from one year to the next couldn’t have possibly forgotten altogether how to be good.

C’mon, that’s Bobby Ojeda out there! He started both Game Sixes!

But, sometimes for better, sometimes for worse, the Mets of “this” year are never the Mets of “last” year. Nevertheless, that year-after sense has carried me, sometimes to my own emotional detriment, through portions of 1970 and 1974 and 1987 and 1989 and 2001 and 2007 and 2017 and 2023 (the years directly after 1999 and 2015 are excused from this recounting as they actually kind of worked out). Then whatever was mathematically obvious about the present would overtake pleasing recent precedent, and I could no longer convince myself that whatever made 1969 or 1973 or 1986 or 1988 or 2000 or 2006 or 2016 or 2022 its own brand of special automatically renewed. That’s still a playoff team, no matter that their record says otherwise was how I thought for as long as I could.

Until the next time their record says something much different from what it says now, I won’t be thinking anything like that about the Mets at all.

by Greg Prince on 22 September 2023 11:16 am Despite indications it might never happen in the course of a year that had only just begun, in their seventh game of 2023, the Mets (3-4) fell below .500 for the first time. So much for white lace and promises.

In their 61st game of 2023, the Mets (30-31) fell below .500 for what turned out to be — if you’ll excuse the expression — good. Watchin’ the signs along way told you there’d be no return above the break-even point.

In their 153rd game of 2023, in which they were defeated by the Phillies in Philadelphia, 5-4, the Mets (71-82) made it official that they’d finish with a losing record.

And yes, we’ve just continued…to lose.

Eleven times over the past fifteen years, the Mets have lost more games in a season than they’ve won. By that very specific metric, this has been the worst fifteen-year period ever in Mets baseball, an enterprise that has been around long enough to contain multiple, overlapping fifteen-year periods and legendary amounts of losing. One wouldn’t intuitively think to measure the Mets by fifteen-year periods, except here we are, having finished under .500 for the eleventh time since 2009.

Which is to say this all feels a bit too familiar.

These past fifteen seasons have included four Septembers that have been more fun than not to blog during: 2015, 2016, 2019 and 2022. Those were the four seasons when the Mets finished with a winning record. This takes into account that the Mets’ bid for a Wild Card fell short in 2019 and the division lead was slipping away as 2022 wound down. Yet in both seasons they were a winning team overall. Until you’ve continuously covered, from an advocacy perspective, a ballclub that spends its Septembers almost never in a position to win more than it loses, you come to value the Septembers when the opposite is the case. A year like 2019, with no playoffs to show for a spirited second-half sprint, and a year like 2022, when a gaudy regular-season record isn’t quite good enough to clinch a division title, are, by comparison to what has otherwise been the norm in these parts, the stuff of a golden age. When you’re dealt years like 2017, 2018, 2020, 2021 and now 2023, the pennant run of 2015 and the followup surge to one night of the postseason in 2016 shimmer as if emblematic of a mythic dynasty — particularly as one remembers the practically unyielding doldrums preceding that two-year interlude in 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014.

Still here, though.

Still mining silver linings, like thinking it was encouraging that almost if not every time they fell behind Thursday night, the Mets came back to tie the Phils.

Still getting excited over the latest prospect who shows a little pop, like Mark Vientos homering again.

Still taking solace in a veteran hitting his stride when he earlier appeared unmoored from his previous form, like 2B-LF-RF Jeff McNeil continuing to play everywhere and hit everything (single, double, triple, a couple of runs, a couple of ribbies, even a stolen base).

Still tuning in whenever the Mets play, wherever they air or stream.

Still planning another trip or two to the ballpark to soak up the last of this next-to-last-place team’s endeavors before they end.

Still reading explanations and gleaning rationalizations for what went wrong this time.

Still writing about the experience for anybody who’s still interested more days than not.

Four winning seasons in the past fifteen. Three that have included extensions of the year beyond was what initially scheduled. One that has gone as far as participation in a World Series. No world championships in any of these fifteen seasons, nor any of the fifteen seasons before these, plus none in however many preceded those until you count back to 1986, which is as close to today as 1949 was to 1986 in 1986. Thirteen winning records in the twenty-two seasons spanning 1987 to 2008. We blogged the last four of those. A couple of Septembers therein admittedly tested the concept of fun with winning records, but any way you cut or collapse it, over .500 is over .500.

In a matter of days, perhaps hours, the losing-record 2023 Mets will also be mathematically eliminated from postseason contention, another formality. At that moment, the “haven’t won since…” clock ticks forward to 38 years, and the 2024/1986 temporal relationship analogizes to 1986/1948. The Cleveland franchise won its most recent world championship in 1948. By 1986, they had waited forever. By next year, their fans will therefore have waited two forevers, meaning we’ll have one under our belt. But, after a while, unless you keep count, you lose count, because when you lose more often than you win so often, it all feels like forever. Fifteen Septembers with eleven seasons concluding on the wrong side of .500 is enough losing to last you a lifetime that you devote to a ballclub that probably doesn’t mean to devote itself to losing, yet there they are, finishing another year when they’ve done exactly that.

And here you are reminding yourself and anybody else who shares your wavelength that first pitch tonight from Citizens Bank Park is at 7:05 PM on Apple TV+.

I’m also reminding you to listen to the latest episode of National League Town, which includes a paean to dashed expectations; a milestone-anniversary remembrance of one of the losing years among the eleven referenced above; and a tribute to someone we lost too soon. Believe it or not, it’s cheerier than it sounds.

by Jason Fry on 21 September 2023 1:15 am So the Mets won two out of three — and could have swept if not for a Gott-forsaken relief appearance — to knock the Marlins off their postseason course, at least temporarily. They’ll now tangle with the Phillies, whose playoff aspirations will be somewhat harder to foil, then host the Marlins, then square off with the Phillies again and then that will be it. Remember the first couple of weeks of the season where you could instantly recall the outcome of every game? This is its mirror image: a few squares left on the calendar, a handful of blanks to be filled in.

There’s some satisfaction in beating the Marlins, of course — my feelings about them have long been clear. But I can’t summon up as much Schadenfreude as I wish I could. Part of that is that playing spoiler is a little too thin a gruel to sustain me, smacking of “if I can’t have this toy nobody can have it.” But never fear, I’m not climbing on that particular soapbox. It’s more that I’ve crossed over to acceptance, and with that has come feeling unhappy that soon enough there will be baseball without any Mets, and soon after that there will be no baseball at all.

And here, near the end, I find myself wanting more, even if it’s not exactly the conclusion to the season we envisioned back in March.

But why not want a little more?

It’s fun watching Mark Vientos absolutely crush two baseballs, on 0-2 counts no less, and wonder what might be if some hitting coach can turn that scorching hard-hit rate into reliable production.

It’s fun seeing how freaking hard Ronny Mauricio makes contact, and to see him materialize in the right spot on the infield, and think about how far he’s come and where he might be headed.

It’s fun seeing Jeff McNeil, that one-man wrecking crew of Marlins hopes, make a jaw-dropping acrobatic play in right to nail Jazz Chisholm Jr. at second base, then finish off the same inning by cutting down Jorge Soler at the plate. McNeil, briefly not displeased with the outcome of a play involving him, all but came off the field blowing smoke off his pistol fingers, and who could blame him?

It’s fun watching Brett Baty, who’s had a trying year to say the very least, connect off Johnny Cueto and remind you that there’s a reason for all the hype. And that 2024 will be a new year and a new start.

It’s fun rooting for Kodai Senga to figure it out on a night when his best stuff wasn’t there and he had to go to pitching improv. A lot went wrong in 2023; signing Senga was something that went very right.

It’s fun watching Drew Smith and Trevor Gott somehow not screw things up. OK, so maybe “fun” isn’t the word I was looking for there. I’m still glad it happened even if I’m not sure how.

When baseball is played crisply and with a little zing it’s so much fun, particularly if you win. And even if you don’t win and even if the baseball’s goopy and soggy — there’s been plenty of that variety chronicled during this season — well, it still has its pleasures. My assignment for myself, as the season’s needle swings with a sigh over to E, is to remember that and cherish what’s left.

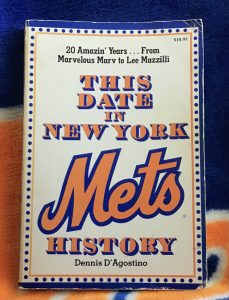

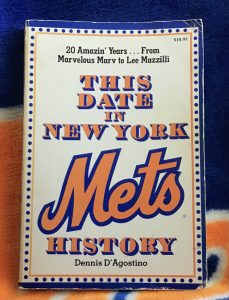

by Greg Prince on 20 September 2023 12:29 pm In memory of the late Dennis D’Agostino and his classic book, This Date in New York Mets History, let’s remember what the Mets were up to on this date — September 20 — fifty years ago, in 1973.

It was time to carefully remove the m-word from the ark in which it had been kept undisturbed for nearly four years, for the fairly recently last-place Mets were about to perform the most sacred act their faith allowed.

It was time for a miracle.

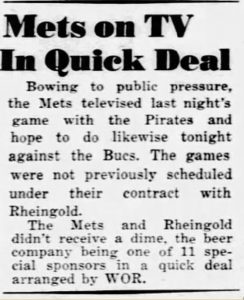

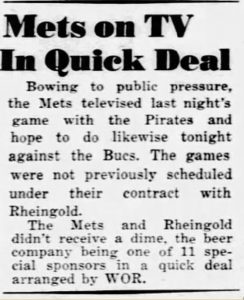

But first, let’s have some bullet points illustrating the relatively mundane from this about-to-be extraordinary Thursday night at Shea Stadium — a game that wasn’t scheduled to be televised over Channel 9, but Mets fans clamored, and the station, along with sponsors like good old Rheingold, among other sponsors, came through. (No matter what historians might tell you, not everybody in New York was watching Billie Jean King take it to Bobby Riggs on Channel 7.)

The people had spoken.

- Jerry Koosman pitched eight innings, struck out eight Pirates and allowed only one unearned run, which unfortunately put him behind 1-0, because Jim Rooker had held the Mets scoreless through seven.

- Jim Beauchamp, making the final regular-season appearance of his ten-year career, pinch-hit for Koosman to lead off the bottom of the eighth and singled. After he was pinch-run for by Teddy Martinez, and Martinez was bunted to second by Wayne Garrett, Felix Millan singled home the tying run.

- Harry Parker, usually a rookie revelation in Yogi Berra’s bullpen, came on to preserve the tie in the top of the ninth but couldn’t quite do the job. Two runners were on when Dave Cash doubled one of them in to return the Pirates to their lead, 2-1.

- Bob Johnson, who pitched two games for the 1969 Mets, was tabbed by Danny Murtaugh to finish off his old team. A win here would erase the Mets’ recent momentum, leaving them 2½ back with a scheduled nine to play. It wouldn’t clinch anything for the Pirates, because others were still alive and contending, but it would put a crimp in the Mets’ plans, no matter much they Believed. But Johnson allowed a leadoff pinch-single to Ken Boswell and a sacrifice bunt to Don Hahn before exiting for Ramon Hernandez.

- Hernandez struck out pinch-hitter George Theodore for the second out of the ninth, but another pinch-hitter, Duffy Dyer, delivered a double, scoring Boswell to tie the game at two.

- The two teams went to extra innings, as Yogi Berra went to veteran swingman Ray Sadecki. Sadecki gave Yogi three perfect innings. The Mets, meanwhile, failed to score against Jim McKee and Luke Walker. The game would go to a thirteenth inning, when Sadecki, with one out, would allow his first hit, a single to Richie Zisk. After he retired Manny Sanguillen for the second out of the inning, he faced September callup Dave Augustine.

This is where The Miracle occurs.

This is where it’s best left to Bob Murphy to deliver The Word:

“The two-one pitch…

“Hit in the air to left field, it’s deep…

“Back goes Jones, BY THE FENCE…

“It hits the TOP of the fence, comes back in play…

“Jones grabs it!

“The relay throw to the plate, they may get him…

“…HE’S OUT!

“He’s out at the plate!

“An INCREDIBLE play!”

If you’re scoring at home, the interpretation would be 7-6-2, Cleon Jones to Wayne Garrett to Ron Hodges, the rookie catcher who ascended to the Mets’ starting lineup for much of the summer from Double-A Memphis because of injuries. Zisk, the runner from first, tied a piano to his back when he took off around the bases. The man was slow. But The Man Upstairs was quick-thinking. He (or Something) prevented what looked like, on Channel 9, a sure home run for Augustine from landing in the left field bullpen for what would have been his first — and only — major league home run. Had the ball made it past the wall, the Mets would have been down 5-3.

But it didn’t go quite far enough, at least from a Pirate perspective. It bounced off the very top of the fence and caromed right back into Cleon’s glove. He made a strong throw to Garrett, who made a strong throw to Hodges, who made a strong stand in front of the plate, bringing down an emphatic tag on Zisk.

“The ball hit the corner and it just popped up to me,” Jones recounted. “I didn’t think he hit it high enough to go over. I knew the ball was gonna hit the fence, but it could’ve gone anywhere.”

Garrett, who had moved to shortstop from his usual third base in the tenth after Bud Harrelson had been pinch-hit for, aimed low when he made his relay throw to Hodges. “I wanted it to hit the ground,” Wayne said, and he got his wish. The ball arrived in Hodges’s mitt the same time Zisk was charging into Hodges’s body. The kid catcher held the ball and home plate ump John McSherry held his right arm upwards, signaling the lumbering Pirate runner out.

“It has to be one of the most remarkable plays I ever saw,” Garrett swore.

The Mets weren’t done being remarkable. The aptly named Walker walked his first two batters in the bottom of the thirteenth. Luke walked off the mound. Dave Giusti walked on. He got one out, but that was all. Hodges, having the night of his career, singled, scoring John Milner from second. The Mets had won 4-3 in a game that would be forever remembered for the Ball Off the Top of the Wall and how it bounced in the only direction it could.

Namely, the same direction the Mets were going in.

This third straight win over the Pirates didn’t put the Mets in first place. It didn’t even put them then at .500. But both of those events would happen the next night, when Tom Seaver would throw a five-hitter to beat the Bucs, 10-2. In a four-day span in September, an unprecedented Metamorphosis occurred. The Mets not only picked up one game per day in the standings, they picked up one place per day. From fourth and 3½ out after Monday, they climbed to first and a half-game up on Friday. It had been barely three weeks since they were in last place. Now they were in first place.

They were in first place. The Mets. The 1973 Mets.

Fifty years ago tonight: you pretty much had to Believe by then.

by Greg Prince on 20 September 2023 8:55 am He may not have had the spelling quite right 46 summers ago, but Marvin Gaye foresaw Tuesday night’s ninth inning in Miami at…I know what it’s called, but I’m not in the mood to acknowledge it Park. After struggling to convert baserunners into runs, and balls hit at them into outs, the Mets dramatically pulled into a tie with the Marlins and made a whole new ballgame of it. And then, because the Mets were engaged in a 3-3 deadlock rather than holding a lead, Buck Showalter entrusted the bottom of the ninth to Trevor Gott to make the same old ballgame of it.

Trevor entered, the Marlins were havin’ a ball. In 1977, Marvin Gaye hit the top of the pop charts with a hypnotic dance floor groove titled “Got To Give It Up (Part 1)”. One “t” in the song’s first word notwithstanding, Marvin was right on the nose, much as a conga line of Marlins would soon be on the basepaths. Trevor’s first pitch was to the body (if not the nose) of Nick Fortes. He’d be the first Marlin on first.

You knew at that point Fortes won’t be the last. Fortes or somebody running in his stead would prevent a runner from standing on second to begin the tenth because they’re wasn’t gonna be no tenth. I’d known since the top of the third ended and I absorbed the R-H-E line score:

METS 1 5 0

MARLINS 0 0 2

We were ahead, but we were finding ways to not be ahead by the plenty more the Marlins were inviting us to be. As the evening progressed, highlighted but not limited to…

a) Joey Lucchesi fielding a bunt and throwing to third base despite third baseman Ronny Mauricio standing next to him and no Met standing at third as a runner approached from second (with Mauricio likely not providing Lucchesi any direction to throw to first as we’ve been told third basemen are supposed to, because Ronny’s a brand new major leaguer and an even less experienced third baseman);

and

b) Garrett Hampson robbing Mauricio of the go-ahead run in the top of the ninth following Brandon Nimmo’s clutch double to rescue the Mets from their own offensive frustration (with Mauricio reminding us that it will be worth enduring his growing pains, because he can really swing the bat)

…the sense crept to the fore and remained in our direct line of sight that the Mets would produce a loss no matter how reluctant the Marlins appeared to inflict one on them.

Buck told Trevor to do what Trevor does, and he responded. In retrospect, it was methodical, but in the moment, it wasn’t easy. Nothing about this game was easy. I watched it with a piercing sinus headache that didn’t get any better from the presence of Trevor Gott. My doctor probably wouldn’t have recommended it, yet there I was, watching Xavier Edwards bunt Fortes to second (with, fortunately, nobody throwing a ball to nobody); Jorge Soler receive an intentional walk (thus delaying the inevitable a couple of minutes); Joey Wendle come in to pinch-run for Fortes; Yuli Gurriel make a productive out to the right side, moving the runners from second and first to the third and short; and then, despite a couple of strikes meant to lull us into a false sense of optimism, Jake Burger line the game-winning single into center. Wendle scored, and the Marlins had themselves an important Wild Card race win, along with their 4-3 revenge on us for getting our revenge the night before on some combination — in my mind, at least — of the 1998 Marlins, the 2007 Marlins and the 2008 Marlins.

The night before, I felt like Daniel Stern as Shrevie in Diner marveling that Tim Daly’s character Billy had just punched out Willard Broxton to get even for something that had happened in a high school baseball game. Neither Shrevie nor Billy (nor Willard) had been in high school for quite a while when this punch was delivered. But Billy swore eternal vengeance after Willard and his entire team had done him wrong in the tenth grade, and he’d get all nine of them — Willard Broxton made it eight — one day, no matter how many days it took.

Beating the Marlins on Monday night in a game the Marlins really needed to have in a year when the Mets just need the year to be over didn’t change the result of that Friday night at Shea in September of 1998 (a John Franco special), or those two out of three in Septembers 2007 (double ugh) and 2008 (double ugh redux) in the same ballpark of blessed memory. In each of those playoff-free seasons, the Mets ended one win shy of where they needed to be to ensure the opportunity to play on. The Marlins were at least partially responsible for all three shortfalls. The Mets were more responsible for not winning enough games in general, yet it is the Teal Menace, with zero otherwise to play for in the waning days of campaigns, we remember as special guest culprits.

Now, FINALLY, the Marlins are in a playoff race that the Mets are not involved in — a Manfred-rigged playoff race, but a legitimate enough one in that it’s taking place over 162 rather than 60 games. The last time this happened was in 2003. The Mets were helpless and hopeless throughout that September, and all those Mets could do was literally let those Marlins punch their postseason ticket in their faces at…I’m gonna guess it was called Pro Player Stadium then. This September, as the Mets have occasionally appeared capable of competing with contenders, they’ve taken games no doubt rued as having gotten away by Mariners fans, Diamondbacks fans and Reds fans. I’ve heard the Mets referred to as spoilers. I did not come into this world with the ambition of, when nothing else of a Met nature was at stake, spoiling the hopes and dreams of fans of the Mariners or the Diamondbacks or the Reds. I enjoyed the Mets beating them, given that I maintain a pulse, but I didn’t take bonus satisfaction from the tossing of a monkey wrench into their respective ambitions.

But when we beat the Marlins on Monday night, doing it as we did on a reversed home run call that screwed them and Jeff McNeil going deep to screw them further, it was as if somebody had just socked Willard Broxton/Hanley Ramirez in the face. Yes! That makes it one!

It would have been nice to have kept up that vibe. For all the evil we attribute to the Marlins, they didn’t actually sweep us in September 1998 or September 2007 or September 2008. I realize it makes a more appealing woe-be-unto-us story to say we’ve never beaten them in a big game, but we came back on that weekend in ’98 to beat them twice, and we memorably won Saturday games from them the last two years at Shea, one pitched by John Maine (almost a no-hitter) and the other by Johan Santana (almost a miracle, as it was on one knee and with no assist, thank goodness, from the bullpen). We even managed to pluck three in a row in Miami the penultimate weekend of 2007 at…I’m gonna guess it was called Sam’s Discount Light Bulb Palace of Sparks then.

The Marlins never had to sweep us in those years. They just needed to abscond with one or two well-placed games to stab us in the heart, or apropos of how I’d been feeling since Tuesday afternoon, the left sinus. Maybe our injecting defeat into their jaws of victory Monday night will make all the difference when all is said and done for 2023. Maybe Tuesday night reset their momentum and we’ll be watching them do Fish tricks in October. Either way, to have taken the first two of this series would have been very sweet and set up the possibility of an even sweeter sweep in front of their long-suffering fan, whose name I have to apologize for not immediately recalling. Buck Showalter, however, didn’t listen to Marvin Gaye. “Got(t) to give it up,” the singer warned the manager. Gaye even helpfully added a “(Part One)” to the record’s label to emphasize to Showalter that this wasn’t going to happen just once.

Gott’s given it up multiple times. But we already knew how that number goes.

by Jason Fry on 18 September 2023 11:44 pm Marlins Nation! We need to talk! Because what just happened?

We just took it to the Atlanta Braves — the mighty Braves! — by sweeping a three-game series and outscoring Acuna and Strider and Co. by a cool 23 runs. There are less than two weeks to go in the season, and the playoffs are right there — it’s not like I need to remind you, but we started play Monday night tied for the National League’s third and final wild-card spot with the Cubs.

Tonight we got to play the Mets, and well, we all know it hasn’t been the best of seasons up in Flushing. Just like we know the Mets and their smug, know-it-all fans deserve it. They’re a gold-plated tire fire, the most expensive collection of baseball players ever assembled, except the big-ticket guys are now gone, sold off and replaced with rookies and Quad-A dudes who make you go, “Oh yeah, that guy,” only it’s entirely possible you’re confusing That Guy with Some Other Guy.

Honestly, couldn’t happen to a nicer team! Anyway, here come the Mets, with some kid named Jose Butto on the mound. This could be a good night — the Phillies are probably out of reach, but we could move a half-game up on the idle Cubs and Diamondbacks and either keep the too-close-for-comfort Reds at bay or push them back a little. All we have to do is beat the Mets, and that hasn’t exactly been a tall order in 2023.

Give this Butto kid credit: He pitches pretty well, showing no fear, and the bad guys take a 1-0 lead in the fifth when Mark Vientos knocks in Ronny Mauricio. Score one for the Baby Mets, but it’s only the halfway point of the game, and we’ve answered back against tougher teams than this one.

And indeed, what did I tell you? We get that run right back in the bottom of the fifth. And then, in the sixth, Butto allows a single to Luis Arraez and leaves a changeup middle-middle to Jorge Soler. That’s a bad idea, and Soler makes the kid pay, hammering a ball high over the left-field foul pole for a 3-1 Marlins lead.

Cue the jubilation — wait, what?

Those Mets are doing Metsy things, crabbing performatively about something or other, but the umpires seem to be listening. And now they’re getting together. No, it can’t be. Soler hit that ball halfway to Mars. Clearly a home run, right? Right?

Wrong. It’s foul. The ruling comes on the field. Skip Schumaker complains vociferously, as he damn well should, but the call for review goes nowhere. It’s foul. Longest damn foul ball in the history of baseball, but foul.

Ah well, no matter. The kid’s got to be rattled by seeing a foul ball that ought to have had a stewardess on it. Soler will straighten the next one out a little, and…

…and he strikes out. Arraez never makes it past first. The game stays tied, and then the bad vibes swim in, like vengeful ghost fish looking for the Red Grooms sculpture.

Phil Bickford — some other anonymous Met I’m not sure is an actual baseball player — can’t find the plate to start off the bottom of the eighth, except with the count 3-0 Jacob Stallings gets one of those dumb automatic strikes called against him. Bickford, given a reprieve, gets Stallings to foul out. He gets the side out in order, but at least the game’s in the hands of Tanner Scott, who’s been pretty much unhittable.

Scott’s third pitch to Jeff McNeil is a slider that McNeil hits over the right-field fence. Yes, McNeil! The one their own fans call a squirrel or something. The vaguely homeless-looking guy who’s always swearing and snarling because he thinks he should go 5-for-5 every game. And it’s pretty much the worst swing I’ve ever seen go for a homer — McNeil’s ass is basically in his own dugout when he connects. Look at the replay and you’ll see Scott can’t believe it, standing there with his mouth a shocked cartoon O as McNeil skips around the bases, probably cursing because he thought the luckest home run in history should have gone even farther.

I hate that guy! I hate all those guys! I hate that half our stadium is their fans when we play them, even in a season that’s seen their half-billion-dollar asses get spanked and end the year trying to stay ahead of the Nationals.

We still have a chance — Adam Ottavino‘s been so-so and my grandmother is about as effective holding guys on. Get a guy on and he’ll be on third for free, then bring him in to tie it up and wait for the Mets to do or not do the kind of things they’ve done or not done all year.

Except let’s not kid ourselves, we can all feel it’s not going to happen. Ottavino goes 1-2-3, ending the game by fanning Jake Burger on three freaking pitches. Oh, and the Reds won, so if the season ended tonight we’d go home.

All because of the Mets! The freaking Mets!

It makes me so mad I could knock down a big expensive sculpture.

* * *

Dear Marlins,

Well, that was heartfelt. I almost feel kind of bad for you. Now allow me a counterpoint:

HA HA HA HA HA

HO HO HO HO HO

HEE HEE HEE HEE HEE

Fuck you Wayne Huizenga, Jeff Loria, Bud Selig, Derek Jeter, Soilmaster Stadium, Luis Castillo and Miguel Cabrera and every single fucking Marlin who ever snuck a ball through an infield in the ninth inning of yet another horrible game played in front of bobbleheads and a big fucking Pachinko thing and fishtanks and a nightclub and all the other stupid shit I’ve forgotten. Fuck you teal and barfed-up neon lettering and calling your team after an entire state when you’re not the only team in that state, and fuck you for not wearing the Sugar Kings alts that are the only good thing about your franchise, and fuck you for being a horrific grift on taxpayers, and fuck you for your cynical, serial teardowns and for being the most benighted franchise in the modern game, the one that should be moved to Charlotte or Montreal or the Ross Ice Shelf or just contracted and never spoken of again except to scare children into better behavior, and fuck you for the fact that Mike Piazza‘s Hall of Fame plaque has to list your stupid misbegotten team, and fuck you for beating the Yankees that one time because I have to be kind of grateful about that, and fuck you for being the rotted-out, reeking black heart of baseball nihilism and an eternal blight on not only the game but also the very idea that anything in the cosmos could be worth preserving.

Oh, and fuck your wild-card hopes, too. At least for a night.

Sincerely,

The freaking Mets

by Greg Prince on 18 September 2023 10:29 am Freddie Freeman having doubled 55 times in 2023 without networks breaking into prime time programming even once to issue bulletins on his chase of 60 — a two-base hit total not reached since the 1930s — has got me thinking doubles are baseball’s most underappreciated hit. Ralph Kiner said home run hitters drive Cadillacs. Tim McCarver thought triples were better than sex. Singles are the currency of the realm, accepted anywhere no-hitters are broken up. Nobody talks about doubles despite the descriptiveness they inspire in the moment.

Bottom of the third Sunday at Citi Field. The Mets have just tied the Reds at one on a bases-loaded wild pitch. Thus, Francisco Alvarez is batting with two ducks on the pond. On the mound once the count goes full, Brandon Williamson, no doubt thinking “I don’t want some New York blogger calling me Wild Willie”, throws Alvy a strike. Alvy swings. The ducks scatter, for down the left field line, Francisco has shot a RINGING double. Here comes Brandon Nimmo with the go-ahead run, here comes Francisco Lindor with the go-ahead-by-some-more run. There standing on second, having rung the bell of the playoff-chasing team managed by David Bell, is Francisco Alvarez with his 12th double of the year, or about half his home run total of 23. Is a double really only half as good as a home run? Is it twice as good as a single? Sunday in the third, it was plenty good in its own right.

Bottom of the sixth Sunday. Tim Locastro leads off versus Carson Spiers. Spiers is the nephew of 1995 Met Bill Spiers. Carson’s skipper is the grandson of 1962 Met right fielder Gus Bell. Locastro relates to Spiers by lofting a fly ball above short right field. It doesn’t fly that much, but it stays in the air a spell and it has its eye on No Red’s Land. It falls in. Tim, a burner, sees he can take advantage of the ball’s elusiveness and hustles. It’s a HUSTLE double! A BLOOP double! No such thing as a bloop homer, and you pretty much have to be Marlon Anderson and receive a lot of luck to Van McCoy your way into a home run if you didn’t clear the fence. Triples have to go far, too. Doubles don’t have to travel all day if the right fellow hits the ball in just the right spot. Alas, Locastro didn’t score, as nobody drove or wild-pitched him in. The Mets were leaving a few too many of their crew to fend for themselves on the bases as the day progressed.

Bottom of the seventh Sunday, one inning after Locastro and two other Mets were left on base, a trio of stranded castaways there on LOB Island. Mets are up, 4-2, the contours of the score not having changed much since Alvarez’s ringing double four innings earlier. Jose Quintana’s own version of few-doubles defense — just one, by Joey Votto, to lead off the top of the seventh — has held Cincinnati in check. Now it’s the Mets’ chance to perhaps double their lead and then some.

Jeff McNeil singles.

Mark Vientos gets on via Spiers’s less than effective throw to first.

DJ Stewart walks.

The bases are loaded, and hustling blooper Locastro is up next, but Buck Showalter sees the same ironic opportunity he spied the night before. Batting for Locastro will once again be Daniel Vogelbach. Locastro usually pinch-runs for Vogelbach. Now Vogelbach will pinch-hit for Locastro. If Yakov Smirnoff had been watching the game, he might have thought, “now, how do I get Russia into this situation?” We don’t know about that, but we do know that in Flushing on Sunday, Vogelbach hit for Locastro and belted a BOOMING double off the center field fence. In Russia, double BOOM you!

All the Mets who could score did score. Vogey even made it to second. An instant after he arrived, he was trotting toward the first base dugout, as he knew there had to be another Locastro in there somewhere. Rafael Ortega indeed emerged to pinch-run for the pinch-hitter who hit for his regular pinch-runner, who started and doubled earlier and played until he was pinch-hit for by the guy for whom he’s made a side hustle of pinch-running for. Also, Rafael Ortega is his own grandpa. Furthermore, Ronny Mauricio drove Ortega home, with a single, singles accepted worldwide.

The final would be the Mets doubling up the Reds, 8-4, with doubles serving their understated purpose of providing extra bases, extra cushion and the spice of life. Ringing! Hustle! Booming! So many different kinds! What variety! Even Sunday’s guest of honor, Bartolo Colon, on hand to “retire as a Met” five years since his last major league pitch, stood as emblematic of the power of the double. The 2016 home run in San Diego is the climax of every Colon highlight reel, but it was when Bart kept his batting helmet affixed to his head long enough to double at St. Louis in 2014 that we’d collected enough evidence to believe all those affirmations of Bartolo’s athleticism. Colon doubled four times as a Met, each instance a little less surprising, because, hey, Bartolo was quite an athlete, which is something they rarely say about Daniel Vogelbach.

Pete Alonso is quite a slugger. He has homered 191 times since coming to the majors. His next home run will tie Howard Johnson for fourth on the all-time Met list. When the season began, Pete sat seventh on said chart, behind Carlos Beltran (149) and Dave Kingman (154). It already seems impossible he was behind anybody but a handful of powerful Mets in the same year in which we sit now, and contract-extending fingers crossed, every Met ever will soon be behind him.

Yet when it comes to doubles, Pete is uninterested in a half a loaf. The fifth-most prolific slugger in Mets history is currently tied for 28th on the franchise’s all-time doubles list, sharing space with Joel Youngblood. If you’re busy hitting home runs, you don’t have as much time for doubles, but the Mets’ reigning home run king, Darryl Strawberry is ninth in doubles; their No. 2 home run man David Wright is No. 1 in doubles; and No. 3 circuit clouter Mike Piazza stands eighth in doubles. Hojo? Fourth in home runs, fifth in doubles, and ranking anywhere you care to place him in the hearts of his countrymen.

Pete’s thrilled us with 45 homers to date in 2023. With two weeks to go, his total will pale only in comparison to the 53 he whacked as a rookie in 2019. You don’t look askance at dollars because they’re not 50-cent pieces. BUT…and it’s not a big but…Pete just does not hit doubles at a rate commensurate with what one would intuitively expect from someone who also hits scads of homers, certainly not this year. To go with his 45 home runs, he has 18 doubles.

Is that not a lot? Historically speaking, it’s not. Beset by curiosity, I punched into Baseball-Reference’s Stathead tool a request for every Met who has ever hit at least 30 home runs in a season. There have been 37 such seasons since 1962. In 33 of those seasons, the slugger who’s gone deep 30 times or more has doubled at least half as often. Sometimes they’ve doubled more than they’ve homered (Bernard Gilkey’s team-record 44 doubles in 1996 were accompanied by 30 homers). Sometimes they’ve homered just as much as they’ve doubled (Beltran recorded 33 doubles and 33 homers in 2007, three years after Mike Cameron opened his own distinct version of the 30-30 club). It’s generally a pleasing proportion no matter how you measure it. In 2019, Pete rang and boomed 30 doubles to go with his 53 dingers. In 2021 and 2022, when Pete was homering 37 and 40 times, respectively, each of his double sums was 27.

Four times, a Met has homered 30 or more times but not doubled at least half as often. Once, barring a sudden and sustained reversal of personal trends over the final 13 games, it will be Pete in 2023. Once, it was Darryl Strawberry doubling “only” 18 times versus his 37 homers in 1990, which is pretty close to half (plus Darryl, perhaps feeling a little light in the two-base hit category, tried to make up for it by stealing 15 bags). Twice, it was Dave Kingman, who was famously all-or-nothing in his approach and results. The two years Sky King blasted exactly 37 homers, he took the under on 18½ doubles: 14 two-baggers in 1976, the year he missed just enough time to just miss leading the National League in home runs; and 9 in 1982, the year he missed the ball altogether a league-leading 156 times. Those 156 Ks tied the Mets’ single-season record for strikeouts in the era when hardly anybody struck out so often. In this century, three Mets have exceeded that number, including Pete, who set the Met strikeout record by a wide margin, with 183 in 2019 and not a soul complaining, given that the Polar Bear was homering 53 times and doubling 30 times.

Nobody necessarily ought to be complaining about Pete’s paucity of doubles in 2023, though it does seem symptomatic of what the 2023 Mets aren’t doing as a whole. Sunday excepted, they’re not doubling all that much. Every single year from 1962 through 2022, the Mets have doubled far more often than they have homered. More midsize cars on the road than luxury models are what one would anticipate seeing, right? Yet in 2023, the numerical comparison is closer than it’s ever been. The Mets have hit 196 home runs versus 206 doubles. “Versus” may be the wrong way to put it All those extra-base hits, including the 19 triples Mets have managed, are working together for the greater Metropolitan benefit.

Brandon Nimmo has 26 doubles, which is three more than his 23 homers. Last year he doubled about twice as much as he homered, although homering wasn’t as much a part of his game as it’s become. It’s never occurred to me to yell STOP AT SECOND as he circles the bases. Francisco Lindor leads the team with 33 doubles, though most of the attention he’s elicited is for his 26 homers and 26 steals. When Jeff McNeil won his 2022 batting title, it was largely on the back of his 39 doubles. This year, with his average down more than 60 points, he has 16 fewer doubles. Tied for fifth on the team in two-baggers, behind Pete’s 18, are Mark Canha and Tommy Pham, each with 15. Given that they stopped wearing Mets uniforms in late July, they’re probably not gonna catch Alonso.

The Mets’ sum of 206 doubles is dead last in the National League. Next-to-last are the Milwaukee Brewers, who, with Mark Canha on their side, are en route to winning a division title. David Stearns put together those Brewers and therefore may not take the Mets’ relative inability to double consistently as a sign that anything is off in his new place of employ.

In 2022, when the Mets won 101 games, they doubled 272 times and homered 171 times.

In 2021, when the Mets won 77 games, they doubled 228 times and homered 176 times.

In 2020, when the world conspired to deprive Pete Alonso of several hundred at-bats in which to hit what has become his usual Herculean amount of home runs (what an inconsiderate pandemic), the Mets went 26-34 with 106 doubles and 86 homers. It’s not the representative sample size to which we’ve become accustomed, but even then, doubles were pulling ahead of homers by a comfortable margin after 60 games.

In 2019, the first year of the Bear, the Mets were pretty good — 86-76 — and doubles (280) outlasted home runs (242), even though the Mets, behind prodigious Pete, set their club mark for most homers in a year.

The most doubles the Mets ever socked in a season were the 323 they pulled or slid into second with in 2006, a year that also encompassed a then-team record 200 homers, plus 97 wins. The home run record was surpassed in 2016, when the Mets belted 218. It was the year when it began to be noticed the Mets either scored by homer or not at all, yet they also added on 240 doubles and went to the playoffs. They hit more homers in playoffless 2017 — 224 — and also more doubles — 286. In 1980, when the Mets notoriously could only match Roger Maris with 61 home runs as a team, they still pounded out 218 doubles.

Good years, bad years, all years the Mets double more than they homer, usually with room to spare. This year, a bad year, it will be close. I don’t know what it says, but I do know it was fun to see them double a bunch on Sunday.

They didn’t homer at all. They won, anyway.

***Sunday commenced with a blot of bad news, as Jay Horwitz announced the passing of his former deputy Dennis D’Agostino, who was only 66. D’Agostino worked for the Mets in the 1980s, following it up with a long term running public relations for the Knicks. He moved to the West Coast somewhere along the way and served as statistician for SNY’s telecasts when the Mets would travel to Southern California. The man did a lot in sports and, judging by the reaction of people who work in the business, made a lot of friends.

I came to know of Dennis in the very early Eighties when he would visit his alma mater’s radio station, WFUV-FM at Fordham. One on One was their late-night weekend sports show. Three hours of baseball talk in the middle of summer. I couldn’t believe such a thing was on the air, even if you had to stay up until two in the morning to enjoy all of it. Annually, around the All-Star break, they’d do a marathon trivia show and have back alumni. One of them was Dennis, who it was mentioned had a book coming out soon: This Date in New York Mets History.

Treasured. My tongue hung out at the notion. A book about the Mets? With what happened every day across the not quite two decades they’d been around? I had to have it! Yet I could never find it. Never is a mighty long time when you’re 18, which is what I was when it was published. My soon-to-be brother-in-law tracked it down for me in time for my 19th birthday. I treasured it then. I treasure it now. You know how you can look up pretty much anything about the Mets today, including all kinds of doubles information? Before This Date in New York Mets History, you could keep every newspaper, magazine, almanac, what have you, maybe figure out a way to get your hands on media guides, comb through yearbooks, arrange trips to libraries…

No, you couldn’t look up all that much outside of the Baseball Encyclopedia, which I didn’t have. Besides, that was just numbers. This Date was as anecdotal as it was statistical. It was informed with heart, soul and warmth that you knew was true orange and blue. Reading it, I instantly understood the author was one of us. He didn’t write about the Mets from any level of journalistic remove or vaguely ironic distance. He wasn’t on holiday from loftier pursuits. Dennis D’Agostino created this volume of everything you’d want to know as a Mets fan because he was a Mets fan who wanted to know everything and was kind enough to share it. He watched the games we watched. We wondered the things we wondered. He found us the answers. He put it one place. The title undersells all that rests between the covers of This Date in New York Mets History.

Dennis wrote other wonderful books and clearly did many things in a life that didn’t last long enough. He also took the time to reach out to this reader many years ago when he learned I said something nice about This Date in one of my books. “For however I might have helped or influenced you,” he wrote, “I truly appreciate it.”

Consider my appreciation toward Dennis D’Agostino doubled.

by Jason Fry on 16 September 2023 11:40 pm Saturday night’s game between the Mets and Reds was one of those close affairs you’re not sure whether to call taut or merely indifferent. The Mets harried Andrew Abbott but couldn’t inflict substantial damage on him; the Reds tormented Tylor Megill but couldn’t put him away either. For the second game in a row, matters turned on a two-run blast by a Red — Jonathan India last night, the prodigiously monikered Christian Encarnacion-Strand tonight.

Though this time the margin was tighter, and so if you were feeling masochistic you could look to a misplay featuring a pair of Baby Mets: Francisco Alvarez loves to make snap throws to the bases, and Ronny Mauricio either didn’t get the memo or couldn’t read it quite fast enough. Alvarez’s throw sailed down the third-base line, TJ Friedl scampered home, and in the end the Mets lost by a run.

Lost, but hey, it’s garbage time. Megill was out there working on things, just like David Peterson was the night before, and those lessons may prove fruitful in some better season down the line. Mauricio got some time at third — albeit with some bruises — and his bat still looks live. Alvarez had a fine game at the plate, which shouldn’t be overlooked in the closing weeks of a season that’s taxed him physically and mentally as never before.

And your recapper spent the afternoon and early evening in a house without power, courtesy of the winds of Hurricane Lee blasting by to the east of Maine. Besides bringing down a critical power line somewhere, those winds felled a big pine that settled across the dirt road to the house.

As an ax wielder, I’m a heckuva blogger. Still, this unanticipated mission was eventually accomplished, and though I braced for a couple of nights of eating Pop-Tarts in the dark, the power kicked back on right after 7 pm, just in time for baseball.

Losing a meaningless game to the Reds? Not really so bad.

by Jason Fry on 16 September 2023 1:56 pm A habit I’m trying to break as a baseball fan is the assigning of blame. If the Mets don’t win – even a stripped-down, playing-out-the-string version of the Mets – it can’t be that the other team won or something went wrong or an unlucky event occurred. No, it has to be someone’s fault.

For instance: Grant Hartwig hung a pitch to Jonathan India, who hit it over the fence, and the Mets lost. That practically has the elegance of a mathematical proof, and hey, it isn’t wrong. I could write that and then follow it up with a lot of grousing about Hartwig, which would probably open the door to complaining about Trevor Gott and Drew Smith as well. If particularly exercised, I might go on to note that David Robertson hasn’t exactly been lights out down in Miami, turning the recap into a lamentation about relievers in general. Note the presence of Alexis Diaz closing the game for Cincinnati while Edwin Diaz watched from the Mets’ dugout and we’d have a full circle of misfortune, regret and simmering annoyance.

And again, none of this would be wrong.

Just maybe … incomplete? Too easy? Pointless?

Buck Showalter was even-keeled when asked about Hartwig after the game, a stance that was probably wise even if it is his job. He noted that Hartwig has had some success and some lack of success and is working on things, learning at a level where he’s never been before. Which isn’t as satisfying as angry postgame lamentations about relief, but also isn’t wrong.

Hartwig relieved David Peterson, another guy whose had some success and some lack of success and is working on things. For Peterson it’s been his slider, which was sharp against the Reds on Friday night. That alone wasn’t enough to get Peterson a win, let alone put his promising turned puzzling career back on track, but Peterson’s quietly been pretty good since rejoining the rotation. And what are 2023’s dregs for, if not Peterson locking down that slider and learning (or relearning) how to make his other pitches work in conjunction with it?

The Mets got even after Peterson fell behind thanks to a three-run bolt from Pete Alonso off the hulking Cincy starter Hunter Greene, one of those homers that’s so immediately and obvious gone that you just beam at the TV and wonder what it must be like to be able to do that. Alas, it was all the offense the Mets could muster, despite a string of pretty good at-bats for garbage time.

The Mets made some mistakes – in the field, and most glaringly with Hartwig’s pitch location against India. They did some good things too. The Reds made fewer mistakes and did more good things. Maybe that will suffice, and the blame game can wait for another day.

by Greg Prince on 15 September 2023 12:28 am Tell me if any of this sounds familiar to your experience regarding your favorite baseball team of late:

• Sometime in early Spring: YAY, BASEBALL!

• A little later this Spring throughout this summer: Does it have to be this baseball?

• Now, as summer blurs into fall: Sigh…there goes baseball, just when the baseball is getting kinda good…

That, I believe, serves pretty accurately as the inverted bell curve charting one’s fondness/tolerance for Mets baseball in 2023. Start out reasonably high; plummet; maybe start climbing anew as events warrant. We’ve won three in a row. That’s the trajectory we’ve been missing.

Another dip is possible over the final sixteen games, because these are the 2023 Mets, and when it comes to going for a dip, they sure do know how to pack a swimsuit. But let’s go with the vibe of the moment, which corresponds to being a little shy of a week from the autumnal equinox. The weather has gone schvitzless, and the Mets have become hitful. Or maybe they’ve just been enjoying the company of the Arizona Diamondbacks.

It was fitting that the Wild Card-contending (a.k.a. a little over .500) Diamondbacks furnished the opposition for the 9/11 commemoration game, because I couldn’t think of another non-New York team that gave a great deal of New Yorkers — not all of them, but plenty of us — more joy when it was needed in the fall of 2001 than the ballclub from Arizona. Bless you, Luis Gonzalez, wherever you are. Letting the D’Backs grab one win all these years later, as they did on Monday night, represented an appropriate gesture of appreciation. Then, with our eternal thanks for saving Mets fans from any further pinstriped deification twenty-two Novembers ago registered, we could return to the present and our uncanny knack for whacking those desert snakes. I don’t know why the Mets usually take it to the Diamondbacks. I’ll just enjoy that they have in nineteen of their last twenty-three meetings, including Thursday afternoon’s 11-1 stomping of the visitors from the West

Ten minutes after four o’clock on a Thursday afternoon isn’t necessarily the most convenient time to commence a baseball game when there are so few remaining in a season and a person might have other tasks looming, but if 4:10 PM starts yield 11-1 wins, well, bring on the inconvenience, not to mention the shadows. This was the last weekday afternoon game we’ll know this year. Everything else is either at night or on the weekend. Everything else is invited to work ten runs in our favor.

I saw some of the game, listened to more of it, missed a little of it, managed to revel in all of it. Deposed champion of batting Jeff McNeil hit another home run. Jonathan Araúz received a rare opportunity to step to the plate and made four bases and three ribbies out of it. DJ Stewart did not add HR to his initials, but he did knock in a couple of his fellow Mets, as DJ is known to do. Brandon Nimmo did something similar. Saving some of that for Kodai Senga‘s next start was not possible, so the Mets piled it on in support one of the league’s best pitchers. Our very own Rookie of the Year and Cy Young candidate struck out ten while giving up no runs, two hits and two walks. His ERA has taken the best dip of all, under 3.00. BBWAA voters take note.

Senga is known more for his forkball than his curve, but the curve the Mets are riding is a most pleasant upward slope. Paying attention to this team any time of afternoon or evening has been something of a sap’s errand this year, but this week will make a person with a selective goldfish memory forget all about that. For example, on Wednesday night, it barely crossed my mind that the Mets have been mostly horrible in 2023. Wednesday night, you see, was when I was fortunate enough to be tapped on the shoulder by a hand from the past.

The hand belonged to Skid.

And by Skid, I mean SKID! You can’t invoke the man’s name without a requisite level of excitement.

Skid Rowe was the prophet of good times to come at the outset of 2015, when this Mets fan from Northern California decided his life wouldn’t be complete unless he spent an entire baseball season in New York going to every single home game the Mets played, and, it turned out, crossing paths with myriad Mets fans who felt blessed to get to know him (I was one of them). He and his experience were both a blast, especially when 81 games at Citi Field proved not enough to suit his proximity to everything orange and blue. Skid showed up, blended in, and the Mets won their division, won their division series, won their league championship series, and went to the World Series. We didn’t win the World Series, but Skid rooted us into November. Pretty good for an out-of-towner.

That was eight years ago. Skid went home to California following the Fall Classic. Long story short, he remained a Mets fan, if not the kind who’d uproot his existence for seven months for the sake of immersing himself in Metsdom. As the late 2010s morphed into the early 2020s, you might say Skid became a Mets Fan Emeritus. Still with us in spirit, just not as all in as he was through the last pitch of 2015. It would be hard to keep up that pace into perpetuity from 3,000 miles away.

Then I felt Skid’s hand on my shoulder. Technically, it was a text and a followup phone call. Through machinations that aren’t vital to recount, Skid found himself with a bunch of seats in his name in the Hyundai Club for Wednesday night, September 13, 2023. It was too long a haul from Northern California for him to be there, roughly an epoch removed from the September days of 2015 that involved counting down a magic number. Yet the seats had Skid’s name on them. Skid’s name is also imprinted on the Mets fan soul of all who consider him synonymous with our most recent pennant.

Skid asked me (plus some other folks from way back when) if…

a) I’d like a couple of those tickets; and

b) I could do my best to see some more didn’t go to waste.

I didn’t want to detail that the September he remembers from 2015 shaped up as nothing like the September at hand when he got in touch, or that a lot of people who love the Mets for better or worse have had their fill of the latter in 2023. Filling those seats, I was thinking, might be a challenge akin to Terry Collins filling out his lineup card pre-Cespedes trade.

Instead, I responded…

a) yes, thank you; and

b) yes, absolutely.

And ya know what? Mets fans answered the call. I was at Citi Field on Wednesday night with others who knew Skid, either from 2015 or by reputation. We filled his seats. All except one he told me he personally hadn’t found a taker for. That’s all right, I thought — you’re supposed to keep a chair open for Elijah the Prophet.

Imbued by the spirit of Skid, we who were there to partake of his largesse had a spectacular time in this, the most dismal of Met seasons. Granted, it helped these seats were in Skid’s favorite section of the ballpark, the Hyundai Club, and the Hyundai Club includes a buffet, and who doesn’t like great seats with great food included? But it’s September 2023 and the Mets haven’t contended for anything but disdain since April; even the most loyal Mets fans could be forgiven for choosing to make their own fun and their own dinner as this season winds down.

This meeting of the Skid Rowe Alumni and Appreciation Society is declared a success. Nope, we members of the Skid Rowe Alumni and Appreciation Society decided, we wanted the fun of being with one another; being with our team, their so-so nature notwithstanding; and thinking aloud about one of us who wasn’t with us on Wednesday night, but we knew he was out there following along via Gamecast, when not checking in with us via a device or two. We wanted a soft summer evening on the cusp of fall. We wanted to watch the Mets stomp the Diamondbacks as they had done the night before, as they would do the afternoon after.

We know a little too well that Hyundai might as well be Korean for aberration. We won’t be playing the Diamondbacks this weekend. Maybe that won’t matter. We won’t be throwing Senga against the Reds. Maybe that won’t matter. The forecast looks good, but you never know with weather. Mets baseball will be gone in a tad over two weeks. We’ll probably be glad to be done with it. It’s not as if a three-game winning streak is suddenly upending standings that have sat on our head without pause.

Yet a few good days after a ton of bad ones, especially when one of the good nights is enriched by so many good friends — and enabled by one who was there in every sense but physical — are to be treasured if you value what loving baseball oughta be all about. We can go back to dismissing these Mets and this season soon enough. Sticking around has its rewards.

National League Town relives the Mets’ journey through the American League, from Oakland to Minnesota and everywhere in between. What a long, unprecedented trip it was. Take it yourself by listening here or anywhere you pod.

|

|