The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 2 September 2023 11:05 pm The Mets played a ridiculously entertaining game Saturday night, once that saw them come back from three runs down and again from four runs down, one that featured a DJ Stewart homer and a Mark Vientos moonshot and a Francisco Lindor screen-rattler, and one that turned, as so many games do, on Daniel Vogelbach using his speed.

Honestly, everything about it was fun except for the final score, which featured an 8 and a 7 in places we wished had been reversed.

(An admission here: Emily and I were at dinner in Torrington, Conn., while the Mets fell behind the first two times, meaning I reported for duty with the forces of good down 7-3. This means that the portion of the game I saw was a 4-1 Mets victory, which unfortunately doesn’t count but made for more pleasurable watching. I highly recommend this as viewing strategy, should you find a way of reliably accessing it.)

Adam Ottavino giving up what turned out to be a fatal homer to J.P. Crawford does not count as one of the entertaining parts: Ottavino is another example of a 2023 Met who’s regressed, though I find it a bit harder to grouse about Ottavino’s backsliding than what we’ve seen from various teammates. Ottavino is a reliever and so knows perfectly well that a good season doesn’t guarantee another good season any more than a bad season is a life sentence. Relievers are spaghetti hurled against a wall; Ottavino stuck the horizontal landing beautifully in 2022, but a lot of 2023 dinners involving him have wound up with pasta on the floor. That’s just the way it goes, which is why the man invariably looks grim and slightly weary on the mound — he’s seen some shit and knows he’ll see some more of it before he’s through.

For a second straight night, Vogelbach was at the center of the game. This time, he led off the bottom of the ninth by spanking a Justin Topa changeup into the left-center gap. Vogelbach rumbled around first, saw the ball on the warning track and shifted into … well, second gear in an effort to reach that base ahead of the throw. It didn’t work: He was tagged out a good foot and a half shy of the promised land.

This was, of course, unfortunate! Vogelbach’s time at first after a single and a more conservative decision would have lasted just long enough for Tim Locastro to replace him on the bag; Locastro might have been on second after a steal (the equivalent of a double if you’re scoring at home and even if you’re scoring in the middle of the desert, looking up the barrel of an abandoned nuclear silo or while peering at the heartbreakingly beautiful blue curve of the Earth from a space station) when Stewart rapped a single up the middle, and that in all likelihood would have tied the game.

After the Mets had lost, various commentators tut-tutted at Vogelbach for pushing beyond his limitations and forcing the issue. And this is indubitably correct … but nevertheless I must protest. On Friday night Vogelbach won a game for the Mets by being aggressive in a situation where we’ve often seen him be passive: He went into protect mode and fouled off a number of close pitches instead of expecting the umpire’s sense of the strike zone to align with his own. He was aggressive again Saturday night in a situation where it was going to take a perfect relay to get him; as it happened, the Mariners made a perfect relay.

You know what? So be it. The Mets tried to play spoiler for a second straight night and almost pulled it off with nine innings of scratching and clawing, playing never say die baseball at the tail end of a season we can’t wait to shovel dirt onto. They played highly watchable baseball after a spring and summer in which too many games bordered on unbearable to witness,. I’ll take that every time — even if the final score winds up not to my liking.

by Jason Fry on 1 September 2023 11:21 pm Fireworks Night in a lost season is always a bit of an asterisk: There are a lot more spectacle-oriented fans in attendance than one might wish, treating the baseball game like it’s the opening band. They wait with varying degrees of impatience, get in your way in the aisles, and annoy you with their conspicuous lack of interest in what’s happening between the lines. If you’re particularly unlucky, they’re even rooting against the Mets, eager for them to finish up and make way for things that sizzle and boom.

(Not that I was there Friday night — I can think of about a thousand better uses for my money than further subsidizing the 2023 Mets — but I remember Fireworks Nights from lost seasons past, and that shit’s annoying.)

I caught the game on Apple TV, which has that Apple quality of simultaneously feeling it’s arrived from a streamlined future and not being something you asked for. The game looks big and wide and bright, with an admirably readable score bug and information, yet a lot of that information seems like it was written up by someone not particularly well-versed in baseball. I don’t particularly trust being told that Cal Raleigh‘s chance of reaching base has increased from 17% to 22% between pitches and more to the point, I don’t particularly care. The announcers weren’t bad — old friend Wayne Randazzo was leading a booth that I think also included Dontrelle Willis (though, again, I don’t particularly care) — but halfway through I remembered a little-known Apple TV feature and switched the audio feed to Howie Rose and Keith Raab. The feed was in perfect sync — now there’s an actually useful bit of Cupertino wizardry — and I rather enjoyed the over-descriptive feel of radio words and TV images, since “over-descriptive” is pretty much what we do here.

I also enjoyed the game, though I kept thinking I was about not to. Kodai Senga was terrific again, Brandon Nimmo socked a homer to match one from Seattle’s J.P. Crawford, and Ronny Mauricio finally made his big-league debut, with his family in the stands determined to make more noise than 30,000-odd fireworks enthusiasts. Mauricio has gained some bulk since I saw him not so long ago as a gawky bordering on extraterrestrial Brooklyn Cyclone, but he’s still all arms and legs and looks like he could use a daily bag of cheeseburgers. But those long arms are powerful levers: Mauricio’s first AB against Logan Gilbert ended with a line drive that rocketed out to right field at 117 MPH, sizzling over the head of a startled-looking Teoscar Hernandez. Mauricio then showed some capable glovework at second, taking a throw from Jeff McNeil in left and tagging out Julio Rodriguez just short of the bag.

(That 117 MPH double, we were told numerous times, was the hardest-hit ball recorded by a Met this season, a stat that’s simultaneously awesome and better left unscrutinized, because who actually cares?)

Mauricio was joined by Brett Baty, returned from Syracuse (he got a knock) and hit ninth behind Francisco Alvarez and Baty. But the game didn’t come down to any of the Baby Mets. Rather, it turned on an eighth-inning confrontation between Daniel Vogelbach and Andres Munoz with the game tied at 1-1, two outs and Francisco Lindor on third. Vogelbach was down 0-2 to start the AB, but instead of watching close pitches he went into protect mode, spoiling four-seamers and sinkers until Munoz’s ninth offering caught too much plate. Vogelbach ended the best AB of his season with a single spanked between the third baseman and the shortstop, which gave the Mets the lead.

So of course Buck Showalter turned to … Drew Smith?

Yes, that Drew Smith, serial allower of home runs and yet another 2023 example of worrisome Met regression. On my couch I reached for my phone and paired word that Smith was warming up with a copied image of “The Scream,” and on your couch you were probably expressing the same feelings though quite possibly in a different fashion. Smith walked Raleigh to start the ninth; picked off pinch-runner Jose Caballero with several Mariners’ looks of disgust bordering on theatrical; coaxed a flyout from Hernandez; but then allowed a single to Dominic Canzone, whoever that is.

The game came down to Smith and Ty France, with Smith seemingly hell-bent on mumping things up. He threw a trio of four-seam fastballs, all for balls, mixing in a slider that hung horrifyingly … but France somehow missed it. So with the count 3-1 Smith went to all sliders. France somehow missed another hanger, then fouled off two more that weren’t obviously disastrous but still caught too much plate for anyone’s liking. “C’mon, hit it to anybody,” I kept intoning on the couch, though what I was really thinking was, “Don’t hit it to some fan sitting 425 feet away.”

Smith threw his eighth pitch to France, which was another slider, I braced for horror — and this slider was, finally, well-located. France swung through it, the Mets had kicked off the Mauricio era with a good one, and I ignored a bunch of elegantly presented meaninglessness on Apple TV. All’s well that ends well, even if you’re not quite sure how it worked out that way.

by Greg Prince on 31 August 2023 11:33 am Just desserts were on the Citi Field menu Wednesday night as the Mets earned their 6-5 victory over the Texas Rangers, and the Rangers just as surely earned their 6-5 defeat at the hands of the New York Mets.

Had it gone the other way, all would have seemed more predestined. The Mets are the lousier team here, they were starting their secret self-implosion weapon Denyi Reyes, and the Rangers, in the thick of a three-way divisional fight with Seattle and Houston and hardly having a Wild Card fallback wrapped up, have something to play for. Of course, it shall be remembered without citing any glaring example that stays with a fan forever, that an out-of-it team starting a pitcher with limited credentials and no reputation (cough, Joe Grahe, who hadn’t won a game in four years, suddenly excelling for the Phillies down the stretch in 1999, cough) can trip up a team with everything to play for (cough, the 1999 Mets, who succumbed to Joe Grahe on that season’s penultimate weekend following getting swept in Atlanta, cough).

But if it were just Reyes shaking off his 15.88 ERA as a starter in 2023 — gathered over two outings that lasted fewer than six innings — and holding the Rangers in check for five-and-a-third, leaving the game with an unlikely two-run lead that set the Mets up for their victory…well, solid pitching from mysterious sources materializes from time to time. Plus, this was the first start in which Reyes’s first name was pronounced “Den-gee” by Mets announcers rather than the intuitive “Den-yee” or Americanized “Denny”. Perhaps this Reyes is somebody else altogether. Or perhaps he hired as his private pitching tutor former Met stalwart Dillon Gee and the lessons took.

The 3-1 lead Reyes protected until the sixth was built in part by a DJ Stewart solo home run. Later, when the Rangers would attempt to protect a lead of their own, Stewart would return to the spotlight and homer again. And, in the tenth inning, the game-winning RBI would be produced by the man Buck Showalter refers to as Stew, because “DJ” is apparently just too formal. Yet with all those sizable contributions — four RBIs plus some extra-base thievery as Stewart threw himself into the ESA ORT portion of a right field fence ad to complete his running grab of Marcus Semien’s sure-thing RBI double — it can’t be said that the Rangers losing was just about DJ enjoying yet another game of his life at the close of the month of his life.

Texas had ample opportunities to overcome Reyes, overcome Stewart, overcome the microscopic detritus of Mets Magic that we’d like to believe still permeates the atmosphere over Flushing. Ample is an understatement. The Mets didn’t dare the Rangers to beat them. They invited them over and brought out refreshments for a Win The Damn Game, Already party. The Rangers simply forgot to RSVP.

When Reyes departed with one out and one on, England Dan and Sean Reid-Foley entered. The Rangers really loved to see him last night. Sean proceeded to walk the ballpark. It’s no exaggeration. The paid attendance of 23,849 each received a base on balls, courtesy of SR-F. Of more use to the visitors, so did Corey Seager, Nathaniel Lowe and Adolis Garcia, all on full counts, all in a row. That’ll manufacture a run. It was 3-2, the bags were juiced and you knew what was going to happen next.

No, you didn’t. The Texas Rangers certainly didn’t. Despite Reid-Foley pitching like nights were forever with him, he struck out Mitch Garver and then Jonah Heim, the latter at the end of his fourth full count and second nine-pitch battle of the inning. Sean threw 35 pitches to five batters. Sixteen were balls. Somehow the Mets were still ahead and the Rangers were still behind.

One reliever would provide stress-free relief for Showalter, Trevor Gott in the seventh (not to be confused with Trevor Gott, stress-inducer in the ninth a couple of nights before). Then came the old pros, Brooks Raley and Adam Ottavino. They appeared to have taken up new professions that did not involve retiring batters. Raley got nobody out as he started the eighth. Brooks was removed literally as fast as a pitcher can be in these three-batter minimum times, leaving the bases full of Texans. Ottavino hit Garcia on a full count to tie the game; teased a double play bouncer out of Mitch Garver that went 1-2-3, as easy as A-B-C if you consider Otto’s backhand flip to Omar Narvaez a piece of cake; and, imbued by the positive momentum the DP had produced, gave up a two-run single to Heim. So much for momentum.

“So much for momentum” might be what Bruce “Boch” Bochy muttered in the Texas dugout when a) a subsequent walk didn’t lead to any more Ranger scoring; and b) Stewart homered for a second time, this dinger delivered with Pete Alonso on base. Yeah, Stew! The game was tied going to the ninth, and Jeff Brigham, who I’m pretty sure had been warming up since being recalled Sunday, was on to keep getting his work in. Two batters saw seven pitches apiece from Brig — I assume that’s what Buck calls him — with one walking and the other fouling out. The fella who walked, Leody Taveras, took second on an errant pickoff throw after not being able to score or even advance when Stewart made that aforementioned sensational catch at the wall. Surely Leody’s getting to second was going to enable a go-ahead run, but no, somewhere amid Brigham’s 23 ninth-inning pitches, Jeff escaped.

After Francisco Lindor walked and stole second with two out in the ninth, and Jeff McNeil punished his bat for popping up with the winning run in scoring position, the game went to extras. Rob Manfred, considerate bloke he is, ordered ahead and had a runner placed on second for Texas. Brigham returned to throw more pitches. One was shot down the third base line but smothered by Jonathan Araúz before it could finish its Citi Field tour as an RBI double down the left field line. Araúz couldn’t throw the hitter, Garcia, out at first, but boy did he keep the runner who had no business being on second, Lowe, on second. Talk about a huge defensive play in extras.

You should, because it’s not the one anybody was talking about first and foremost in a couple of minutes, for Garver walked to again load the bases for Texas, and with one somewhat conventional out made (Lindor catching a sizzling liner from Heim), Old Friend™ Travis Jankowski stepped up to presumably pull a Travis d’Arnaud or James McCann or ex-Met of your choice and do the Mets in. Jankowski wasn’t here very long. He was 2022’s Terrance Gore in the months before Terrance Gore became 2022’s Terrance Gore, a role played intermittently in 2023 by Tim Locastro. We mostly saw Jank — that had to be his clubhouse nickname, right? — pinch-run as a Met. Bochy uses Jank as semi-regular outfielder. Bochy’s managed three world championship teams. We’ll assume “Boch” knows what he’s doing.

Every reason you could think of for why the Rangers were about to take a tenth-inning lead vaporized in a blink. Jankowski grounded to Alonso, moving in front of first base toward foul territory. Alonso rightly threw home. Jankowski, reacting in a sense of self-preservation lest Pete’s throw inadvertently clock him, slowed down and ducked. While Narvaez received Pete’s throw and recorded the first out, Travis turned his head toward home for an instant, perhaps thinking, “why wait for highlights when I’m on the field and get to watch a big play develop in person?” This slowed the speedy Jankowski substantially, allowing time for the Mets’ new ad hoc first baseman, McNeil, to complete his race over from second to take the return throw from Omar.

Jankowski had both hit and run into a 3-2-4 double play. It got Brigham (40 pitches over two innings and at least as many thunderous claps of his glove in exultation in appreciation of his defense) and the Mets out of the inning right about the time the Rangers should have been planning their happy flight. Travel home to Arlington was on somebody’s mind when this game was scheduled for a 6:40 start. Now Texas was stuck in New York a little longer.

A game in which Mets relievers threw 128 pitches over four-and-two-thirds innings couldn’t possibly be blown by the Rangers, yet it was about to blow the Mets’ way. With McNeil standing on second as Manfred’s gift to the hosts, Bochy ordered the intentional passing of Pete. First and second, nobody out, the accomplished yet apparently exhausted Aroldis Chapman on the mound. If the Mets were the Mets of most of 2023, it wouldn’t have necessarily been a recipe for Texas disaster, which, if you ever happen to be in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex, isn’t nearly as tasty as Texas barbecue. But the Mets rose a little above their station all night and the Rangers seemed determined to let this one get away. Sure enough, Francisco Alvarez, who had taken over the DH duties from Daniel Vogelbach (who himself had homered way back in the second), gritted his way to a full-count walk — Alvarez still isn’t hitting much, but he does dig in for some tough at-bats when the conditions are late and close — and DJ Stewart made his body available for a bases-loaded plunking. Heroics, schmeroics, it was the game-winning RBI. McNeil jogged home, Stewart was showered with a bucket of bubble gum (wrapped), and the Mets, who are about to add Ronny Mauricio to their ranks for their stretch drive to nowhere, had one night to feel very good about themselves.

The Rangers, who really had to work to absorb a loss they definitely didn’t need in their AL playoff chase, had a long flight ahead of them, courtesy of the team that’s headquartered the shortest of hops from LaGuardia.

by Greg Prince on 30 August 2023 12:03 pm Kudos to the Mets for scheduling the finale of their series versus the Rangers tonight a half-hour earlier than usual. The 6:40 PM start time, slotted in deference to Texas’s travel itinerary, isn’t a secret, but it will no doubt take some habitual viewers and listeners by surprise. The Mets begin virtually all of their evening home games at 7:10 PM. Not a few people will tune in then only to find the Mets and Rangers already in progress.

Those are lucky people, and I’ve figured out a way to create even more fortunate souls. Just keep starting Mets games earlier than expected, a little bit more each night or day. Did we say 6:40? We meant 5:50. You thought first pitch was at 5:50? Oh, we went with 5:20. Listen, we know we said 5:20, but 2:30 seemed more convenient. We hope you don’t mind.

Mind? Mind? If you kept getting your games over with without what’s left of our attention directed at them, we’d thank you for flushing this dreaded 2023 Met habit from our system.

If we had no idea when their games start, we’d hopefully take the karmic hint and slither slowly but decidedly from our rut of seeking the Mets out in the name of some kind of bizarre fulfillment. So by all means, try to sneak these games in when we’re not looking and we’re not listening. The worst that will happen is we’ll have to find out about yet another low-scoring loss — like Tuesday night’s in which Jose Quintana pitched wonderfully and the infield defense performed admirably behind him, only to have nobody score on his behalf and Drew Smith enter and throw his patented home run ball — after the fact. The resulting fact on Tuesday turned out to be Rangers 2 Mets 1, typical for what happens when These Mets play some contender. The Rangers wheedled an additional run to set up an impenetrable two-run lead heading to the bottom of the ninth. Mark Vientos proceeded to hit a home run with one out remaining, nobody on base and the Mets down by two. Hence, they lost by one.

Actually the worst that will happen will probably be tonight, when Kodai Senga will be allotted additional rest and Denyi Reyes will be brought up to quite likely reprise his performance from previous spot starts, and the loss won’t be so low-scoring. I take that back: the worst that will happen will be remembering to tune in at 6:40 so as not to miss a single pitch of Mets baseball, whoever throws how many it takes to finish losing.

Or, I suppose, winning. You never know. You pretty much do, but you actually don’t. I plan to tune in and report back, dammit.

by Jason Fry on 28 August 2023 10:43 pm These games are the bottom of a can of soda your buddy just handed back to you after taking way too big of a sip, so that the can is 90% empty and you start thinking about what percentage of what’s left is backwash, and then … ehh, come to think of it you’re not really that thirsty.

Cans like that start off perfectly pleasantly — a sweet fizzy drink on a hot day — and so it was with Monday night’s game against the Rangers. Tylor Megill pitched well, then bent instead of breaking the third time through the enemy order when some of the steam came off his pitches. Rafael Ortega played some good defense in left, Brandon Nimmo and DJ Stewart went deep — it was refreshing.

But then came the ninth, and Trevor Gott being asked to secure a one-run lead, and it was time to give what was left in the can a suspicious shake.

I’ve written about changing my tune on Ortega and Stewart and even Jonathan Arauz, though I do kind of wish Arauz could hit. But Gott I’ve had no use for, and Monday night’s game didn’t exactly change my mind. Gott gave up a single and a double within five pitches, leaving the fall-behind run a single hit away before recording an out — and sending me to Twitter to grouse at everyone and no one. (I’ve mostly quit Twitter — oh, sorry, I forgot that jackass renamed it X — for Bluesky, but Bluesky is still sparsely populated and mostly nice, meaning it’s a poor fit when you need to vent your spleen.) Having dug himself a hole, Gott then fanned Leody Taveras and Marcus Semien, making me wonder if I’d have to issue a mea culpa after he Houdini’d his way out of trouble. Which, let me make it abundantly clear, would have been fine — one of many marvelous things about baseball is how often you’re happy to be wrong.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t wrong. The Mets gave Corey Seager a free pass to first, which was only sensible. But then Gott missed badly with a 1-1 sinker to Nathaniel Lowe, forcing him to give Lowe something to hit. Against the Cardinals in a similar spot Gott made a perfect pitch to Paul Goldschmidt. He didn’t make one to Lowe — he left a cutter elevated which Lowe whacked between first and second, almost but not quite clipping Seager on its way to the outfield grass. The Rangers led 4-3 and won by that score after dealing with a bit of Met kicking and bleating in the bottom of the ninth, and we were done.

Honestly, my only question at this point is how the hell Gott managed to retire Goldschmidt.

by Greg Prince on 28 August 2023 9:43 am As one who doesn’t subscribe to Peacock, I couldn’t tell you what Sunday’s Mets-Angels game looked like, but from the sound of it over WCBS-AM, it was quite the staring contest. The Mets stared at the Angels. The Angels stared at the Mets. It was 0-0, 1-1 and 2-2. Two teams used to staring into the abyss had at last encountered their respective match. Who would withstand who? Who would blink first, or simply nod off?

The Mets, that’s who. The Angels blinked. Or got tired of staring a little sooner on a sleepy afternoon. The game started at 12:05 PM following a Saturday night affair. Barely enough time to listen to American Top 40 on SiriusXM’s ’70s channel and then shift dulcet tone gears from preserved for posterity Casey Kasem to alive and well Howie Rose & Keith Raad. First pitch probably ate into a few pregame naps.

We just spent three days in the company of an outfit I’ve long considered our Southern California spiritual brethren (early 1960s expansion roots; enormous market with a suburban bent; overbearing neighbors; never enough enduring success), yet this version of the Los Angeles Angels, for all the starpower their one standing star brings wherever he goes, felt like an assortment of Anaheim strangers. Shohei Ohtani needs no introduction. Four certified Old Friends™ — Brandon Drury, Aaron Loup, Eduardo Escobar, Dominic Leone — constitute a portion of his traveling party. Plus I seem to catch a few innings of the Angels late at night via the MLB Network every couple of weeks. All of that, and I swear they seemed more of a mystery by the last out Sunday than they did when they arrived on Friday.

This series drew well, presumably owing to the Ohtani factor. Watching and listening to the crowd reaction, especially from those draped in his Angel and WBC gear, I was brought back to the influx of McGwire and Sosa idolaters at Shea when the home run virus spread far and wide. I was surrounded by people wearing Cardinal or Cub jerseys who I were pretty sure couldn’t have named any other Cardinal or Cub. They surely weren’t interested in the Mets’ best interests, and my resentment boiled. Ohtani’s acolytes, the first two nights, didn’t bother me. His celebrity speaks for itself, and whatever the Angels did, it didn’t threaten to trip up a Met playoff chase. Shohei the showman was giving those folks what they came for. Cheers for his hits and steals meant something went wrong for the Mets, but things have gone wrong for the Mets without much pause in 2023. At least somebody at Citi Field was giving some people there something to cheer about.

In the finale, however, when Ohtani went hitless, particularly the two times he struck out, I could hear a torrent of boos pervading the Mets’ ballpark. I don’t care how transcendent a figure he is. I don’t care what good he does for baseball. I don’t care that we’re in last place. The striking out of an opposing batter by a Met pitcher is not to generate anything less than tacit approval at Citi Field. That’s my rule and I’m sticking to it. Once Ohtani made his fourth out Sunday, I was ready for the Ohtaniacs, like the McGwirephiles and Sosascenti, to take a hike. (I mean, sure, come back if the guy wants to sign here, but we’ll deal with that chicken when it crosses the road.)

Escobar got a nice hand, which was deserved. Eduardo’s Met tenure now seems ages removed, as if he was part of the crew that ran roughshod over the National League in 2006. Nope, it was only a year ago he was a part of better days, only this year he was going down with the ship before being offered a leaky lifeboat in the form of a trade to the Angels. He played only in the last game of the weekend set and doesn’t seem to be of much everyday utility to Los Angeles of Anaheim. Nevertheless, his presence had me yearning for days of barely yore. I kind of hoped he’d pull a Coffee Black from the ABA tribute movie Semi-Pro and, like the charismatic player the doomed Flint Tropics had recently traded, drop his red warmups, cross the diamond to the Met dugout, and tell Lindor, McNeil or anybody he recognized, “I’m with y’all.”

Whoever the hell the rest of the Angels are and whoever the hell the rest of the Mets are got it on in professional enough fashion. No Mets tossing the ball around the infield after the recording of an inning’s third out like happened Friday. No Angels zinging one off their own pitcher’s noggin after the catcher threw to the absolutely wrong base (there are only three of them) as transpired Saturday. Pete Alonso’s own melon avoided contact with flying objects, thank goodness. Pete looked good, driving in one of those runs that produced one of those aforementioned tie scores.

The other Pete looked great. The other Pete is David Peterson. Buck Showalter regularly refers to David as “Pete,” which is confusing for the home viewer (SNY gets to do a postgame show even when Peacock struts on a Sunday). Well, the David otherwise known as Pete could be described as a godsend if a higher power could possibly be concerned about who would lift slack for These Mets after a veritable bullpen game the night before. David took care of seven innings and gave up only one run in the process. If “Pete” is really what he’s called internally, then he earned his clubhouse nickname, because that was a powerful performance, even if it was equaled by Angel starter Griffin Canning. That’ll happen in a staring contest.

Drew Smith succeeded Peterson when the score was 1-1 in the eighth, and immediately threw “the home run ball,” as Howie called it, which made me think that’s a pitch Drew (or Smitty) should remove from his repertoire at once. Fortunately, the Alonso commonly known as Pete drove in the shortstop known as smoking hot with the run to make it 2-2. The shortstop is Francisco Lindor, now on a thirteen-game hitting streak, which is better than whatever the other Francisco has been on. Catcher Alvarez has been navigating the slumpiest of waters — his August falloff is historically reminiscent of what another Met rookie strongboy, a slugger named Ron Swoboda, went through in 1965 (15 homers before the All-Star break, only four thereafter) — but maybe, just maybe, he’s set to come out of it, having made enough contact to concoct an infield hit in the fourth, a grounder Angel second baseman Luis Rengifo (the same guy who’d hit Smith’s home run ball later) could only smother. The Mets appeared to load the bases as a result, but spunky Jeff McNeil — urged on by spunkier Alex Cora — raced from second to home as the LAA infielder struggled to his feet. That’s how we scored our first run, the one Peterson guarded as a lead clear to the seventh.

That was the essence of the staring contest for eight-and-a-half innings. Once Adam Ottavino retired the Angels in the top of the ninth, a person listening at home debated the likelihood of Rob Manfred’s fugazi extra innings, given a) that the Mets are the Mets when it comes to scoring; and b) the Angels, though I don’t know them well, seemed pretty damn Metslike in their ability to let a game get away. The PointsBet folks would have gladly taken my action either way, I’m sure.

Alvarez got himself grazed by a pitch, which will circumvent any slump (it was close enough for the Angels to challenge, but it stuck). No dugouts emptied and young Francisco was no worse for the ding. Tim Locastro came out to pinch-run, which made sense, not only because Locastro is faster than Alvarez, but because Daniel Vogelbach had already been hit for. “It’s not like I only wait around for Vogey to get on base, you know,” Locastro’s thought balloon says. “I can run for anybody!”

With Locastro on first, DJ Stewart singled to right, which was characteristic (dude can rake some) and a wee bit ill-placed, because the Angel right fielder, Hunter Renfroe, has an arm of which to be wary (a tidbit I picked up from my radio friends). Mark Vientos, back from the IL, never had a chance to knock in the winning run or, for that matter, ground into a double play. He took his four unintentional balls from reliever Reynaldo Lopez and liked it. So did we.

OK, bases loaded, nobody out. What the fudge is gonna go wrong? That was my thought when Rafael Ortega came up with a chance to win the game. That was also the thought of my counterpart across the country, the Angels fan who’s rooted for them as long as I’ve rooted for the Mets, except his “gonna go wrong” was directed at his own object of affection/derision. I rooted hard for the 2002 Angels to win the World Series because I imagined I had a veritable doppelgänger living somewhere in SoCal and I sure wanted that guy — around 40 years old at the time — to get one title after all he’d been through. If he’s still out there, having passed 60 and still searching for a sequel, he was on his own Sunday.

Me, I had Rafael Ortega. And now I will always have Rafael Ortega, even if the Mets won’t after this season ends. Ortega ensured his sliver of Met immortality by sinking a fly ball along the edge of No Man’s Land, or at least not inside Renfroe’s zone of defensive comfort in right field. Hunter nearly made a stumbling catch that would have likely resulted in Locastro tagging up and scoring, because however strong the right fielder’s arm, his angle wasn’t optimal to make an effective throw.

But why take any chances? Better that it fell in for a single, sending Locastro across the plate cleanly and turning the heretofore space-filling Ortega into a Met walkoff wonder. Immediately, I found myself in mind of Austin Jackson, the last outfielder I can remember the Mets picking up to help them get a season (2018) over with who managed to sneak a walkoff hit onto his permanent record. Jackson’s action stays with me thanks to the circumstances surrounding his auspicious occasion: it was David Wright’s final game, which SNY shows a lot. That one did go into extras, to thirteen, back when extra innings featured only the baserunners who earned their way on without commissioner’s assistance.

Ortega is also part of a slightly larger, harder to narrowly define cohort. Or might ultimately be. Jackson’s part of it. Nori Aoki, (2017) too. If we include pitchers, Aaron Harang (2013). Going back a bit further, you have your Cory Sullivan (2009), your Wilson Delgado (2004), your Kevin Bass (1992). These are the major league veterans who transcend mere Met-for-a-minute status (reflexive Random Met citings need not apply). They suddenly showed up on the Mets in some second half when the Mets were going absolutely nowhere and were now a part of our lives on a surprisingly regular basis, playing almost every day or, in Harang’s case, slotting into the rotation for more than a test spin. We’d never seen them coming Metwise, and we’d never see them again in orange and blue. They weren’t brought in to help us win anything. They were here to give us a hand so we could limp toward the finish lines of seasons that were over before they were over. They played a bunch, then they completely disappeared from our Met consciousness.

I thought that might be DJ Stewart’s legacy, but Stewart is a comparative rock of this organization now, so maybe it will be Ortega, owner of a certified Mets walkoff RBI single, who inherits the mantle of what we might call this season’s Dead End Achiever, when the greatest accomplishment of all is coming to the ballpark, putting on a Mets uniform that may or may not have been measured to fit, and soaking up innings/at-bats. Should a walkoff hit emanate during that time on the clock, all the better.

We won’t know if Ortega’s highlight(s) as a Met will lead him to a dead end. For all we know, we’ll see him in camp next February and he’ll be a valued part of the team for many a Sunday to come. Same for Stewart or Jonathan Araúz or anybody else who’s seeped into our field of vision long enough to morph from “who’s that guy?” to “oh, he’s batting sixth tonight”. Maybe all the 2023 Dead Enders are making a case as essential Mets in 2024 and beyond. Probably not. But until proven otherwise, they persevere as Mets and continue to earn “hey, ya never know” status.

The Mets themselves, meanwhile, don’t yet have a skull-and-cross bones next to their name in the standings to denote mathematical elimination from postseason consideration, but the very final ember of remotely conceivable longshot possibility is on the verge of extinguishment. After the 3-2 win over the Angels on Sunday, the Mets sit at 60-71. Win tonight versus Texas, and they are 61-71. That record is what the 1973 Mets were as of August 30, the last day they languished in last place. From there, everything we know and cherish about the efficacy of You Gotta Believe began to kick in in earnest, inadvertently casting a pale glow on any Met team stumbling in near total darkness for five months across the fifty years that followed.

The 1973 Mets didn’t just win one of history’s most unlikely pennants. They created an almost impossible precedent for which Mets fans have grasped when there is nothing left to grab hold of. Our sweaty hands, despite a plethora of playoff spots seemingly there for the taking this year, have kept coming up empty these past five months. The 61-71 Mets of a half-century ago stayed within wishing distance despite occupying the bottom of the National League East, creeping to within six-and-a-half games of first after being double-digits behind earlier that summer. The pack came back to them before they made their biggest move; objects in the front windshield proved even closer than they appeared. Should everything break right tonight, the 61-71 Mets of 2023 will be only eight games out of the final Wild Card berth in the National League with thirty games remaining, and you know what that means.

It means we’ll be one day closer to this dead end of a season being over.

by Jason Fry on 27 August 2023 8:17 am The Mets lost, which is once again what they do: Carlos Carrasco was awful again and at this point one has to conclude he’s hurt, done or both; the bullpen was superb but it didn’t matter, as the offense didn’t hit enough or hit when it would have been useful.

The dregs of the game brought a jolt when Pete Alonso got hit below the helmet by Jose Soriano — a breaking ball, but an 88 MPH breaking ball, as this is 2020s baseball. (Seriously, by 2033 changeups will be delivered at 103 MPH. Shit’s insane.) Alonso took offense and there was some milling around and close talking; after the game, Buck Showalter fumed and talked about not saying certain things in public, which kind of sounded like retaliation is forthcoming.

Now there’s a way to complicate the Mets’ potential pursuit of Shohei Ohtani, the baseball unicorn looking at a year or so of settling for mere legendary thoroughbred status.

Which got me thinking….

Ohtani, late 2033: “With free agency upon me I had decided — though for obvious reasons I couldn’t tell anyone — that I wanted to be a New York Met. The fandom is so intense and knowledgeable, and I wanted to be final piece of the puzzle in returning that club to its rightful spot atop the baseball hierarchy. But then some pitcher of theirs — was it Peterson? Megill? honestly I could never tell them apart — hit me in the finale of this super-meaningless series, and I just lost all respect for them. I mean, hit O’Hoppe or, I dunno, drop Phil Nevin during the lineup exchange, but you’re going to risk injuring the reason everyone came to the park because some million-dollar arm, ten-cent head kid couldn’t control his breaking stuff? Does that really make sense? Plus the game was played at like dawn and was on some ridiculous network called Peacock, so I was already in a bad mood. Anyway, they made their choices and I made mine. And, well, my choices meant the Texas Rangers became a dynasty, starting with the late-career renaissances of deGrom and Scherzer, and their choices … let’s just say it’s sad to see what that club’s become.”

Or I dunno, maybe Ohtani, late 2033: “With free agency upon me I had decided — though for obvious reasons I couldn’t tell anyone — that I wanted to be a Seattle Mariner. There’s so much great coffee there, and I just love the Space Needle as an example of brash, optimistic architecture. But then, in the finale of this super-meaningless series against the New York Mets, their pitcher Peterson dropped me with a fastball in my first AB. He was defending the Polar Bear, who’d been hit the night before by one of those million-dollar arm, ten-cent head guys on our roster. So as I was lying there looking up at the belly of Delta 5696 to Charleston I thought, ‘This is the kind of fighting spirit that’s been lacking in southern California,’ plus I realized I could not only get coffee anywhere but was also about to have enough money to straight-up purchase Colombia. So I decided to sign with the Mets. I taught Peterson and Megill a few things and, well, the last decade kind of speaks for itself, doesn’t it? No, winning the World Series doesn’t get old. Oh, and I did buy Colombia and am very proud to have made it into the high-tech mecca and showcase of primary education it is today. Want a coffee?”

Hey, like the man once said, you never know.

by Jason Fry on 26 August 2023 1:32 pm After a brief flurry of optimism or at least acceptance, garbage time is officially back. Before the season, a late August Mets-Angels tilt looked like one to circle on the calendar. Who wouldn’t exult in the prospect of watching Pete Alonso and Kodai Senga go up against Shohei Ohtani and Mike Trout on two playoff-bound teams?

It didn’t exactly work out that way. Trout is on the shelf as per the unfortunate usual, Ohtani’s UCL injury has produced a cloud of questions ahead of his assault on the free-agent record books, and both teams have seen their seasons curdle into things you carry out to the can with your arm stretched out as far as you can and as stoic a look as you can muster.

Senga pitched well — there’s one Met roll of the dice that’s worked splendidly — and Ohtani showed off his sizzling bat speed and deceptive speed afoot, but this was a game that faded into the lost-season blur seconds after it ended. I kept waiting for the Mets to come back and pay homage to the Marlon Anderson Game, one of the first gems we got to chronicle as rookie bloggers, but that never happened. The closest the Mets got was Joey Cora‘s seventh-inning decision to send Danny Mendick homeward as the prospective tying run on Brando Nimmo’s not very deep fly to left. Right call because Randal Grichuk would have to make a very good throw to get Mendick and it’s not like the Mets were getting a bevy of chances? Wrong call because Francisco Lindor was up next and Grichuk would make the catch practically breathing on the shortstop’s neck? Whatever your opinion, the historical record will show that the ball beat Mendick by a country mile, Mendick came into home as if arriving for tea, and the Mets were done.

Done, and in last place at the end of the evening. Which is kind of amazing — the GDP of a decent-sized nation was spent for this? — and yet not surprising at all to those of us who keep watching this train wreck for some unfathomable reason. Ask your therapist if masochism is indeed right for you, as treatment is available and covered by many insurance plans!

* * *

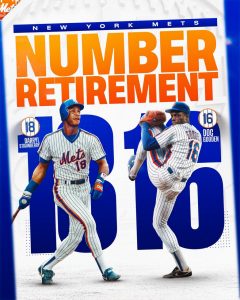

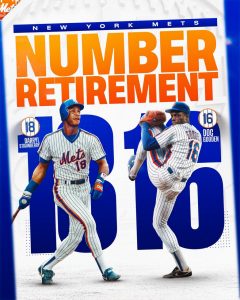

In happier news, the Mets announced that they’ll retire 16 and 18 next year for Dwight Gooden and Darryl Strawberry, a revelation that Greg weighed in on here. Which got me thinking about retired numbers, a baseball topic that’s dear to my heart.

Teams are, of course, all over the map in terms of retired-numbers philosophy, from the stinginess of the Dodgers and Mariners to the ludicrous bacchanal of the Yankees, which has spurred at least semi-serious talk of stripping managers and coaches of numbers and/or players wearing triple digits. The Mets started off in the stingy camp, retiring just 37 14 41 and Jackie Robinson‘s 42, but have since done an about-face, removing 31, 17, 36 and 24 from circulation before giving the nod (or maybe it’s the shake of the head) to 16 and 18.

Read this next part with this big flashing light in your head: There’s a BUT coming.

I mostly agreed with the Mets’ stay-small philosophy on retired numbers, even while suspecting it was more about the Wilpons’ cheapness and Dodger fetishizing than any kind of coherent world view. Before it happened I thought they should retire 17 for Keith Hernandez, but only because of his second act as a broadcaster — his record in uniform, while marked by a title, struck me as a bit too slight for a retired number on those grounds alone. I was fine with the idea of putting away 31 for Mike Piazza, the icon of his Mets era, but figured the Mets would get to it eventually. I saw Jerry Koosman as a companion star whose light was always lost in Tom Seaver‘s glare, which isn’t fair but is also relevant to this particular discussion. Willie Mays‘s time at Shea was, to me, simultaneously a lovely tribute to his indelible career and an object lesson in the perils of staying too long at the fair — fascinating but not obviously the stuff of retired numbers. And Doc and Darryl, while Mets immortals to me, were sadly more examples of what could have been than what was. Retire 8 for Gary Carter? My view was that while I’d always love Carter as a Met legend and see him as a Hall of Fame person, the numbers from his tenure were frankly pretty skimpy.

That stance was indelibly shaped by something else: I liked the tacit philosophy the Mets held for years, which was to have certain numbers unofficially retired — the Kelvin Torve farce aside, 24 was mothballed except for generational players such as Rickey Henderson and Robinson Cano. I liked that as a secret status because it was a nod to team history that was also a deep cut — a reward earned as one grew into more of a Mets fan and delved into the team history. If anything, it was a stance I wished the Mets would employ with other numbers: Koosman’s 36 was a prime candidate in my mind, as was 45. Put those two things together and I was pretty happy with the state of affairs.

(OK, here it comes)

BUT

When the Mets retired 31 for Piazza I wasn’t mad. I was delighted. Same for Koosman, and Hernandez, and the masterfully executed ceremony in honor of Mays. And when the announcement came about Doc and Darryl my first thought was, “that’s awesome.”

This is why I think retired-numbers arguments might be the only truly good arguments in baseball. I feel passionately about my own position on the subject, but the Mets have gone in another direction and each time they’ve put that new direction into practice I’ve thought, “let me see if I can get tickets.” Every semi-reasonable outcome is a perfectly good one, a chance to celebrate the team, its players and its history. It matters in a way that’s fun to debate, but it Matters not at all. And that’s a relief.

Where do the Mets go from here? It’s a lock that they’ll put 5 up in the rafters for David Wright, which I just hope comes with a nod to Davey Johnson — if the wild card had existed back in the 1980s it’s entirely possible Davey never gets fired and 5 never becomes available. I’m sure they’ll retire 8 now that Keith and Doc and Darryl are being honored, and that’s as it should be. I think they ought to retire 45 in tandem for Tug McGraw and John Franco, who are linked by not only their roles as closers but also their status as clubhouse leaders.

In my mind that would be enough. Though if the Mets keep going and put aside, say, Jesse Orosco‘s 47 or Howard Johnson‘s 20 or Al Leiter‘s 22 or whichever number it’s concluded Ron Darling wore most often? I’ll think that’s awesome too.

by Greg Prince on 25 August 2023 11:55 am Darryl Strawberry was coiled to swing. Doc Gooden was set to fire. The seconds in which they locked in constituted the most compelling moments in sport, maybe life, in their time at the core of our consciousness. The results tended to tell you why, but it was the anticipation that had us leaning forward. Anticipation will do that.

Hold your head up. Keep your head up. Movin’ on. I anticipate 2024 for the raising of Strawberry’s 18 and Gooden’s 16 to Citi Field’s bustling rafters, two retirement ceremonies whose announcement appropriately came a little out of left field on Thursday, unless you were watching the Mets intently (was there any other way?) in the days of Darryl and Doc. Had you been magically transported from 1984 forty years forward and landed to witness 18 and 16 hanging high atop a facility in the general vicinity of Shea Stadium, one of your most logical questions might be, “How do they keep those placards so immaculate, so looking like new, considering how long ago the Mets must have retired the numbers of the most spectacular hitter and the most spectacular pitcher they ever brought to the majors?”

Then, once you got your bearings, maybe you’d ask why the Mets are so modestly displaying only a single championship banner from the decade when Doc and Straw broke in. You’d probably have lots of questions.

What we know in the present, with four decades of hindsight, is that Darryl Strawberry was the most phenomenal position player the Mets ever developed or acquired in their first sixty years of operations, and that nobody ever regularly took control of a baseball game with such total unhittability on behalf of the Mets as Dwight Gooden. In order of the efficacy of his five tools, Straw hit with power, ran, threw, hit and fielded, very much able to do it all, very often doing tons of it. Doc needed two pitches to get batters out, and routinely took care of almost all of them with a high fastball and a curve that dove as if on an underwater treasure hunt.

To call them both electric is validation for Thomas Edison’s wildest hopes and dreams. To call them successful speaks to what they contributed to our decreasingly wild hopes and dreams as the early 1980s gave way to the middle 1980s. When Bob Murphy closed his call of the final out of the 1986 World Series with, “The dream has come true,” there was nothing generic to Murph’s championship coda. The Mets fan dreamed of a reality like the one forged largely by Darryl and Doc before the Mets fan ever heard of Darryl and Doc, before Darryl and Doc ever heard of the Mets. It and what these two young men represented stood impossibly far away before we encountered and embraced them individually, professionally and in the company of teammates assembled, in practice, to make the most of what they had to offer. When they channeled their respective talents and mastered their respective crafts, the world in which we yearned to live — wherein everything was about the Mets, not just for us but for everybody who peeked their head into big league doings — came to exist. The Mets were its centerpiece, its capital, the axis on which it spun. As of October 27, 1986, the Mets were its champions.

But much of the real fun was in the anticipation, the hoping, the dreaming, and all of it coming to pass, first via the uncoiling of Strawberry’s bat in 1983 (when he won Rookie of the Year) and then the firing of Doc’s first deliveries in 1984 (when he won Rookie of the Year). The Mets climbed from Nowheresville, where they’d resided approximately forever, to somewhere close to winning it all, then even closer, then winning all of it. That was Darryl swinging, Doc throwing, not a few other very important Mets doing their things, and the chemistry and appeal and excitement and immersion generated by this New York Mets scene jumping off the charts. If you were to choose, you’d choose never to retire from the era in which Darryl was up with a chance to some damage and Doc was a strike away from setting down the side in order.

It felt like it would last forever. It didn’t. They felt like they’d last forever. They couldn’t. They couldn’t last as Mets and they couldn’t last as the best at what they did for as long as every concerned party, from the most seasoned scout to a reasonably discerning fan, would have projected. Darryl Strawberry and Dwight Gooden were people. People who were absolutely great at playing baseball, people who played absolutely great baseball in tandem, people who played absolutely great baseball on an absolutely great baseball team. They didn’t do it forever. They did remain people.

The 1986 Mets’ world championship banner sits adjacent to the 1969 Mets’ world championship banner over in the right field rafters. Then the championship banner parade glides down a notch to National League championships, none won from the days of Darryl and Doc or any of their contemporaries. Squint and you’ll see something about a division title a couple of years later. Go back to the area over the left field seats next year, and there will be Nos. 18 and 16, anyway. They did so much, just not everything. They won the big one, just not multiples of them. They were who they were. They have persevered as people and were around Thursday to accept the news about their numbers with gratitude and pride.

Their numbers, once they are hung, will be the eighth and ninth retired specifically by the New York Mets. Two — 37 and 14 — rose to rafters to honor managers, so we’re talking seven players out of 1,216 Mets overall, as of the day the Strawberry/Gooden announcement was issued, receiving the franchise’s ultimate honor. One, 24, is a category of its own. So let’s take Willie Mays out of the equation. Willie Mays will always belong in his own category as a baseball player. Willie Mays defies equations.

Of their 1,215 baseball players who weren’t Willie Mays, the Mets have now opted to retire numbers to commemorate the careers and contributions of six of them (with the understanding that revered manager Gil Hodges wore 14 as a Mets player, too). This implies the Mets have retired one number for a little more than every 200 players who’s donned the orange and blue, which is to say that of every 200 or so Mets who come along, the organization recognizes one as incredibly special in the sweep of its history.

Two, 41 and 36, belong to the one-two pitching punch that made that first world championship banner and so much more possible…plus 41 is a category of its own in a Metsian context.

One, 31, belongs to the singular icon of his very if not ultimately successful Met age.

One, 17, is a flag planted in the lunar soil on behalf of the greatest of Met eras, and it was right that 17 was affixed to the rafters first among Mets of his generation, for it was Keith Hernandez who led the Mets’ mid-1980s expedition to the moon and the stars.

But that crew didn’t get there just from its captain’s savvy, clutchness and ability to corral everything hit to him around first base. The 1986 (and 1985 and 1984) Mets revolved around Darryl Strawberry coming of age and Dwight Gooden arriving almost fully formed and the two of them getting us to look up, up and sometimes away. Their numbers, 18 and 16, are going to be up there now.

I’ll look; and I’ll look back on looking ahead; and I’ll look back again, and I’ll love what I see for what I saw when the sky was their limit. ’Cause, y’know, they reached it for us plenty.

by Greg Prince on 24 August 2023 9:36 am SNY spotlighted a clubhouse interview after Wednesday night’s game as if it was news. Francisco Lindor said the Braves were better than the Mets. This is news in the sense that this just in: Studies Show Pleasure Preferable to Pain.

What’s the scoop here? That one of the Mets’ leading players recognized that the team that beat his 10 of 13 times in 2023 and leads his by 24 games in the standings might maintain an edge by way of head-to-head comparison? I watched all 13 Mets-Braves games this year. I’m still wondering how we won three of them.

Since Atlanta moved to the National League East in 1994, they have finished with a lesser record than New York exactly five times: 2006, 2007, 2008, 2015 and 2016. Twice the two clubs tied: 2014 and 2022, although the latter tie isn’t really recognized as such. Once 2023 is over, the Braves will be 23-5-2 in this regard, though I doubt they spend a lot of time regarding themselves vis-à-vis the Mets. Conversely, when Steve Cohen bought the franchise and pointed to the Dodgers as his role model for consistency, perhaps he should have stayed within the division for aspiration. Atlanta is about to win its sixth consecutive NL East title and 18th overall…and they didn’t even arrive here until 25 years after the division was founded.

That’s a great team over there and this one over here is not. Of the ten Met losses to the Braves this season, Tuesday night’s 3-2 would-be heartbreaker (had we any heart left to break) was an exception in that it felt like it just got away or was there for the Mets’ taking. I know there were a few other close ones when the season was younger and not so obviously over, yet I was almost always permeated by the sense that the Braves were going to come along and grab them — including that dizzying night in June when the Mets took or increased a lead in five separate innings yet the game ended 13-10 in the Braves’ favor — because that’s what that team does. They’re talented, they’re deep, they’re relentless and they expect to win games. It’s what they do, it’s who they are.

Wednesday’s adios to Atlanta was close until it wasn’t, which is another hallmark of Mets-Braves games. Jose Quintana struggled somewhat but kept the Mets in it until he couldn’t and they weren’t. The Mets did next to nothing against Charlie Morton, a veteran I never realize is as grizzled as he is. You couldn’t tell from his pitching. The 39-year-old (who relieved for the Braves in a September game the Mets really had to have in 2008) struck out eleven over seven innings and would have had a no-hitter going if not for the double stylings of DJ Stewart. His two two-base hits and continued hot hitting burnished one of the legit feelgood stories of the dog days of August, though it felt less good when DJ stumbled after the first of them while taking a subsequent lead and got picked off second by catcher Sean Murphy.

That was in the fifth, when the score was only 1-0, Braves. By the end of the sixth, it was 5-0, Braves. Marcell Ozuna, who had a Troy Tulowitzki of a series, did damage. So did Murphy. So did pretty much every Brave. The final wound up 7-0, but the vibe was very much 21-3 from two weekends ago at Citi Field. These Braves may not score plenty early, but they score frequently eventually. One saving grace is they were ahead by enough and perhaps bored enough to go down in order in the eighth inning, which meant Sean Reid-Foley could claim a successful comeback from Tommy John surgery. Reid-Foley last pitched in the majors sixteen months ago, when the Braves were four-time defending NL East champions. Perhaps it was comforting for Sean to know, that for all he’s gone through in terms of rehabilitation and for all the new rules that have been codified within the sport in his absence, some things about baseball never change.

A new episode of National League Town is on tap. Fill your mug and enjoy!

|

|