The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 9 October 2024 10:36 am As I was getting out of my uniform, Jerry Koosman, whose locker stood next to mine, was slipping into his street clothes. “Wrap it up tomorrow, Koos,” I said. “I don’t want to go back to Baltimore. That place makes Fresno look like Paris.”

“I’ll get ’em,” Jerry said. “I don’t want to go there either.”

—Tom Seaver, The Perfect Game

The whole of the 2024 Mets experience as it stands right now is equal to the sum of its parts, because the parts are so wholly terrific.

I liked the part where the pit of my stomach was added to the postseason roster. This was around 3:30 Tuesday afternoon, as SNY’s extensive pregame coverage kicked off with live shots of Citi Field, and at last, it seemed real that the Mets were going to play home playoff baseball. With that realization that Game Three of the National League Division Series had landed in Queens, it got real real deep inside of me, where I usually feel it this time of year when we have this time of year. It was already very real, and I’d been alternately excited and anxious for more than a month, but this represented tangible emotional escalation. I not only had proverbial skin in the game as a Met fan. I had actual acids churning there, too.

I liked the part where Griamce boarded his specially branded 7 train car and was immediately immersed in a Mets fan group hug. The Grimace thing has gone from eluding me to tickling me. Think of all the purple trick-or-treaters you’re gong to see in a few weeks and how much candy they’ll earn for their costumes.

I liked the part where, on the Mets’ YouTube page, I was able to watch pregame introductions. We saw so many Mets who weren’t eligible to play in the postseason (unlike me and my stomach acids), but they were sanctified as a part of this, too. Jeff McNeil. Drew Smith. Brooks Raley. Brett Baty. Christian Scott in a cast. Alex Young. Pablo Reyes, who pinch-ran once; was designated for assignment; passed through waivers untouched; and now rides with the taxi squad. Hayden Senger, that catcher we called up to keep handy in case Francisco Alvarez didn’t recover from a bat to the facemask or whatever it was that left him a little more than stunned in Milwaukee or wherever it was. So much has happened so fast. So many people have come and gone. Getting this far has a team effort that can be hard to keep track of without notes. Let’s hear everybody’s name called at least once in October.

I liked the part where we forgot Pete Alonso was ever enduring a power drought, let alone the part where every next Pete Alonso at-bat at Citi Field was potentially Pete Alonso’s last at-bat as a Met at home. The Mets had been on the road when Pete the pending free agent regained his power stroke (and how). Now he was where he belonged, putting a baseball where it belonged, way the hell outta here off Aaron Nola for a second-inning 1-0 Mets lead.

I liked the part where Jesse Winker stood to make absolutely certain that his fly ball soaring somewhere toward the vicinity of College Point Blvd. stayed fair. He was just being careful not to expend extra energy taking several steps down the line before ascertaining it wasn’t foul. No, he wasn’t ostentatiously admiring his ostentatious surefire home run to make it Mets 2 Phillies 0 in the fourth inning. Not our Jesse, who can play it any way he wants as far as I’m concerned.

I liked the part where Winker didn’t wasn’t flummoxed by any frustration he might have carried from his previous at-bat, when he was robbed at the alcove wall by Nick Castellanos and rightfully confused by the umpire who called it a non-catch because Castellanos juggled and dropped the ball on the transfer. Jose Iglesias had been on first and had to hold up before dashing to second. Winker stood on first with the longest single in Citi Field history, until replay got it a) right and b) sensible. Winker was ruled out, but Iglesias was allowed to retreat to first despite not tagging up and all that implied once the ball returned to the infield, as right field ump Edwin Moscoso, who didn’t have the best angle on the play, had waved his arms in the “safe” motion. It didn’t lead to any runs, but it also didn’t cast a we can’t get a break pall on what was left of a sunny afternoon in Flushing.

I liked the part where defense came to play. Mark Vientos nailing Alec Bohm at first on a bounding ball that required a mighty fling from foul territory. Tyrone Taylor expertly playing a ball off the right-center field fence and firing a pea to Francisco Lindor to tag Bohm before he could slide into second. I guess I like Bohm being out repeatedly, but I could say the same for any phamiliar Phillie. We know all of them all too well at this point.

I liked the part where Sean Manaea faced little to no trouble most innings and emerged unscathed the inning he encountered just enough turbulence to make the stomach turn. He walks Kyle Schwarber to lead off the sixth after having him down oh-and-two. He walks Trea Turner to make it first and second with nobody out in a 2-0 game with Bryce Harper coming up, hoo boy. Harper, to be followed by Castellanos. This movie didn’t turn out well on Sunday in Philly. But this was a new release in a different park. Our park. Sean struck out Harper and induced from Castellanos a double play liner to Iglesias. Another clean inning where it counted.

I liked the part where the tension of a tight ballgame began to dissipate once Starling Marte lined a bases-loaded single into center to score two with two out in the bottom of the sixth. It was an opportunity cashed in, the kind of thing a team determined to win makes happen. (For the record, I imagine all teams are determined to win, but some show themselves more skilled about manifesting their determination.)

I liked the part where Manaea threw seven pitches to retire three Phillies in the seventh, suggesting he might not be done before the eighth.

I liked the part with the other enormous bases-loaded two-run single, in the bottom of the seventh, this one from Iglesias, who, like Marte, didn’t waste the chance to add on. His big hit made it 6-0, and I noticed the pit of my stomach had been taken out for a pinch of relaxation.

I liked the part where although Manaea allowed a single to lead off the eighth, and Phil Maton and Ryne Stanek each gave up hits that led to runs, I didn’t have to scramble and get some worry up in the bullpen. It was gonna be fine, I told myself without needing to convince myself. Francisco Lindor doubled in the Mets’ seventh run in the bottom of the inning, Stanek settled in for the ninth, and the Mets won, 7-2, pushing themselves to within one victory of taking this series…at home.

I loved — LOVED — the part where Carlos Mendoza and his players calmly answered queries in the postgame presser with postseasoned veteran aplomb. I had the sense the reporters were in the same headspace their predecessors were that May night in 1969 when they rushed into the Mets clubhouse in Atlanta after New York reached .500. The Mets had never reached .500 after a season was three games old before, so of course they’d be celebrating. Instead, the players were changing clothes and looking forward to the next game. “You know when we’ll have champagne?” Tom Seaver asked. “When we win the pennant.”

The Mets are so much fun and have so much fun on the field. Yet they are the opposite of the old saw about colorful teams that are all business once they cross the white lines. It’s back in the clubhouse that they emerge out of a phone booth as 26 Clark Kents, mind-bogglingly mild-mannered about their exploits. Very appreciative of the attention they have stoked (they’re the ones who gave us OMG, to say nothing of Pete’s Playoff Pumpkin), very happy to be here, but not at all impressed that they are here. The clichés about just doing what they can, having another game to play, passing the baton, et al, sound so gosh dang genuine coming from them. It’s the “they got this” ethos incarnate. I’ve come to believe it all stems from Mendoza, who has said on more than one occasion — including after Game Three — “we haven’t done anything,” as if he were taking cues from Stevie Wonder. When they lose and he’s asked if it has to do with the stress of the schedule or the impact of injuries, the response usually includes “nobody feels sorry for us.” When they win, and the yearning among the media is for a quote that might pump up the narrative volume, it’s “we haven’t done anything.” Of course they’ve done plenty, but they plan on doing so much more. No (ahem) wonder every question they were thrown about how great it would be to clinch the NLDS at Citi Field in Game Four was purposefully fouled off in service to the grind. As Stevie also intoned, gotta keep on trying, ’til you reach your highest ground. A one-game lead after three games of a best-of-five is, for this team, a mere plateau.

I will confess to having had a few sips of champagne on the off night between the Wild Card Series clincher and the Division Series opener. A nice pizza as well, as is Prince family wont when the Mets make the postseason. Circumstances weren’t optimal for our traditional as-merited autumnal celebration when the Mets assured themselves of a playoff presence after they beat the Braves two Mondays ago, so the sliver of respite bracketed by finishing off the Brewers and taking on the Phillies had to do — and it did just fine. Loved the champagne. Loved the pizza. Loved the feeling. I’m for celebrating everything the Mets accomplish. Leave that to the fans. Today, albeit sans bubby, I celebrate that the Mets are respectfully declining the presentation of any participation trophies.

by Greg Prince on 8 October 2024 8:37 am Shortly after Shea Stadium completed its sixteenth season of operation as home of the New York Mets, it was busy being the home of the New York Jets. The Mets were done for the year by October. This was 1979. Competitively, the Mets were done for the year by April.

Citi Field is currently in the Shea equivalent of 1979 chronologically and in no other way. Citi’s sixteenth season, 2024, turned into the sweetest sixteenth imaginable. Beyond the Mets fan imagination, really. Opened in 2009 to high anticipation, the facility became known among frequent visitors as home of the meh. The aesthetics sparkled. The baseball wasn’t much to look at. Gleaming doesn’t cut it for very long if the team in residence doesn’t extend its seasons very often.

It took until Citi’s seventh season, 2015, to get Shea up in here. By the time Shea had been around seven seasons, Shea had established itself as the home of miracle and wonder. Season Six was 1969. The World Series came to Shea. The world championship, too. Three clinching celebrations in a span of just over three weeks trampled the grass. Maybe the groundskeepers minded. Surely the Jets — contractually dispatched to a lengthy away schedule — weren’t thrilled. But Shea, from 1964 forward, was where we had fun even before we won. Then we won, and there was no place on Earth like it. Could you blame us for digging up some earth?

Citi needed a modicum of success to tap its potential. That’s where 2015 came in. That’s where postseason baseball came in. That’s where fun came in. The Mets have never clinched anything at the ballpark that succeeded Shea, but starting in 2015, they began to get the hang of keeping it open in October. Seven postseason games that fall; one the next fall; three two falls ago, when there was a very hard fall. Victory at Citi has been intermittent in autumn (statistically speaking, 5-6 might belie the concept of home field advantage), but save for the San Diego finale in 2022, the vibes have been immaculate.

Nobody was shocked when Shea rocked. I think we were all taken aback that Citi could shimmy and shake. We who were there nine Octobers back changed the reputation of Citi Field. It wasn’t the building that was blah. It was the baseball and our response to it. Shea invited you to be giddy for the sake of giddiness when it opened. Citi wished to show you a menu. Once settled in Queens, Mets fans were ready for 1969 long before 1969. Come the next century, the Met mood had to find its place in its new place.

Open for postseason business…and fun. Since 2015, we know Citi Field has a pulse and a heartbeat. Each throbs extra loud when it hosts extra games. Through their respective sixteen seasons of operation, Citi actually leads Shea, 11 to 10, in serving as a site for Upper Case October Baseball. Today and tomorrow will make it 12 and 13 for Citi. Shea sizzled in October 1969 and October 1973 (teeth chattered in the latter month’s World Series, but we’re talking Met-aphorically). Then it went on a long autumnal hiatus…except for the Jets, and even they took off after a while.

Shea came back strong in October 1986. Later, there’d be a handful of Octobers when mojo rose, if not as high as desired. Still, it was always a handful for opponents, thanks to the building and its occupants — players and fans — working their respective magic. I’ve never much associated Citi Field with magical properties. Some magical moments, absolutely, but it was too stately in its construction to include pixie dust. Yet these 2024 Mets are nothing if not magical, and we know damn well they’re not nothing. To us, the way they’ve gotten to October and fought into October, they’re everything. Until today, they’ve been everything but the home team.

The world’s longest road trip of Atlanta to Milwaukee to Atlanta to Milwaukee to Philadelphia, with an impending hurricane and two champagne showers thrown in, is over. The Mets went everywhere and all they brought us was this wonderful opportunity. Citi Field’s gates open at 2:30 this afternoon, 43,000-some sets of vocal cords shortly to follow, no doubt reaching an apex pitch before first pitch at 5:08. The din will erupt from deep within. We’ve waited long enough to express our in-person postseason’s greetings.

by Jason Fry on 7 October 2024 10:39 am There was a wonderful moment back in Atlanta, one that’s nearly been forgotten in all the joyful, exhausting tumult of what’s followed.

Steve Gelbs was interviewing Francisco Lindor, only Gelbs was drenched in alcohol and having trouble getting past the fact that his eyes were burning.

“You’re suffering!” said an even more drenched Lindor. “You’re not embracing! Let it happen — make it part of you.”

Lindor was mostly teasing Gelbs — mostly, but not completely. He wasn’t wearing goggles either. But his expression was serene.

What he’d told Gelbs, I found myself thinking later, was pretty good advice — and not just for baseball.

Sunday’s game was another barn burner, just the latest Mets game to shove its way into the ranks of the classics. Luis Severino looked sharp from the beginning, mowing down the Phillies, and the Mets grabbed a lead behind home runs from Mark Vientos and Pete Alonso, both of whom hit homers that just cleared the fence in right-center: Vientos off a Cristopher Sanchez changeup left in the middle of the plate, Alonso off a high curve from Jose Ruiz.

3-0 Mets heading into the bottom of the sixth, and the Phillies fans were restless, booing their own. For shame, Philadelphia. In a playoff game? After the season they gave you? Seriously, I thought the role played by the fans in the redemption arcs of Alec Bohm and Trea Turner had put this Philadelphia narrative to bed, but there they were giving it a new lease on life.

I wasn’t booing the Phillies, but I also wasn’t sanguine about how things might turn out: Sure, Severino looked better than he had in weeks. But there were 12 outs to get and this is Citizens Bank Park, where any lead feels like the decimal should be moved one place to the left.

Severino got the first two of those 12 outs but then looked like he started overthrowing, maybe because he knew his day was ending. In the course of eight pitches it all came unraveled: single to Turner, Bryce Harper home run that came down somewhere in central Jersey, sweeper annihilated by Nick Castellanos. Just like that it was 3-3,

Punch them back, I urged the Mets, having seen my share of Citizens Bank donnybrooks over the years. And they did: Brandon Nimmo homered off Orion Kerkering to give the Mets back the lead, albeit one now reduced to a skinny run.

My new superstition? When relievers come in with a lead, I matter-of-factly ask, “Where are we going to find [X] outs?” Then I greet the new reliever and solemnly suggest he not fuck it up.

Jose Butto, last seen fucking it up in Milwaukee, hit J.T. Realmuto (not ideal) to start the seventh, got a pair of outs, then lost Knockwurst Clemens on an unplayable infield single, with Knockwurst’s disgusting father watching from a luxury box instead of being frog-marched off to the Hague. That brought the Phillies’ lineup clicking back over to its deadly top three, as it seemed to do about every five minutes in this game, and brought in Edwin Diaz, who got Kyle Schwarber to swing over a backfoot slider to avert further harm.

The thing that struck me at this juncture? It was that both teams looked exhausted, less standing up on the dugout rail than clinging to it. Games like this one will do that to you — as well as to the hundreds of thousands of fans living and dying with every pitch they can’t affect.

I urged the Mets to score, oh, 10 or 11 more runs, but they eschewed that advice and sent Diaz back out for the eighth. (“Where are we going to find six outs? Don’t fuck it up, Edwin.”)

There’s nothing easier or cheaper than a second guess, so I’ll say right here that I like the way Carlos Mendoza has handled the bullpen over this insane last week. He’s been aggressive and he’s been innovative, not blindly plugging guys into roles they played in July or August. And most importantly, no one has reported for duty looking like they were caught unawares. It made sense for Diaz to face Schwarber instead of Butto, and it made sense for Diaz to stay in to face Turner and Harper.

Unfortunately, there are at least two other factors at work right now. One is that the bullpen has been sorely worked, particularly Diaz. The other is that regardless of workload, Diaz’s entire season has been a nightly psychodrama: You never know if the fastball is going to be high 90s or mid 90s, if the slider is going to be low and sharp or high and flabby, and you never know how much conviction Diaz is going to bring to his pitches.

Diaz vs. Schwarber has historically been a good matchup for Diaz, but as he navigated it I’d winced at too many sliders sitting above the knees. There were more of them as Diaz went to work in the eighth, fanning Turner but then walking Harper (also historically a good matchup for Diaz) on four pitches. Castellanos singled on a high fastball, and against Bryson Stott (and his oddly soothing sing-a-long walkup music) all of Diaz’s pitches were up in that flashing red danger zone; his sixth pitch was a slider that sat middle and didn’t slide, and Stott spanked it down the right-field line for a triple and a one-run Phillies lead. A batter later, with Tylor Megill now pitching, Vientos tried to throw home before he secured the ball and Philadelphia was up by two.

Not good, but these Mets have shown me over and over again of late that nothing is impossible and improbable is just another way of saying “hasn’t happened yet.” Harrison Bader flied out to start the inning against Matt Strahm and up came Lindor.

Baseball is a game of failure (perhaps you’ve heard), with a hitter contending against not only the best pitchers in the world but also ample opportunities for misfortune through no fault of his own. But Lindor’s play since returning from back issues has been simply remarkable, silencing the critics who, for whatever reason, have spent his entire Mets tenure eager to find anything to pounce on. Baseball doesn’t make anything a certainty or even more likely than not, but right now if something needs to be done Lindor will do everything in his power to maximize the chances that it gets done.

He singled off Strahm and up came Vientos. Vientos is in an interesting place right now: He’s made tremendous strides as a player during a transformative season. But he’s still a young player, there’s a difference between sleepy summer matinees and October cauldrons, and it’s asking a lot of the baseball gods to expect a young player who’s already delivered to deliver again.

Strahm, meanwhile, is one of those guys who makes his money by throwing gas high and wrinkles low (and why not, it’s the way you’d pitch God Himself if you were handed that unenviable assignment), and at 1-2 he had Vientos set up for the slider below the strike zone. Vientos ignored two of them and Strahm went back to the fastball. The one he threw was at the top of the zone, if not somewhere around Vientos’s chin, and verging to the outside. Vientos somehow didn’t just hit it out but pulled it out to left-center — ah, bat speed and being strong as an ox — and the ballgame was tied once again.

OMG, you might say.

It would be nice to put a bow on this recap right here, but duty compels me to march on, into the vale of shadow: Megill got the first two outs in the bottom of the ninth but then walked Turner and Harper. He got the first two strikes against Castellanos, yanked a slider into the dirt and then hung one. Castellanos spanked it into left, where I presume someone eventually picked it up after Nimmo headed briskly for the visitors’ dugout.

If the Mets had been allowed to keep going, I wouldn’t have been shocked to see them score one run — or two, or however many would have been needed. But nope, the rules dictated that was it — the Phillies had won, 7-6, sending Castellanos to a joyful Howaboutthat? with his son in the front row (c’mon it was sweet) and sending the series to Citi Field tied at one.

Here’s one of my favorite baseball parlor games: Down a run or two late, would you rather your team come back only to lose via some even more cruel twist of the screw, or just see them come up short now?

On Sunday the Mets opted for “even more cruel,” but I don’t regret that extra turn of the screw at all. They lost, but they went down spitting and hissing, scratching and clawing, on the short end of a riveting game that delivered everything except the conclusion we wanted.

We’re all along for what’s become a crazy ride. So far it’s brought unbelievable helium wheees at apexes along the track, as well as stomach-imperiling lurches after unsafe drops. But we’re strapped in and we’re not going anywhere until we’re told that’s it, that’s the end, everybody off. Until that moment comes, opt for embracing, not suffering. Make it part of you.

by Greg Prince on 6 October 2024 12:25 pm The New York Mets broke it to me gently early Saturday evening. They appreciate my help, but they got this. They have a plan, they know what they’re doing, they’re going to do it, I can just relax. I nodded my understanding. I’m not going to relax, but I think I get what they’re telling me.

They do got this. They know something the rest of us don’t. We are free to clutch our talismans and hail our Grimaces and hashtag our OMGs and, now that it’s a thing, pick our pumpkins. We also have their blessing to fuss and fret and stress and sweat over each individual pitch and swing. We can think that we shouldn’t be thinking this or that, lest we affect the action far from where we sit or stand. We can go about contorting ourselves into lucky shapes or avoid leaning in the wrong direction. We’re not going to make a difference, but if we want to believe we have that power, more power to us.

It’s the Mets, however, who have the power, even when they limit themselves to eight singles and five walks. It’s the Mets who have the gleam in their eyes, the assurance in their manner, the knowledge that this is their October. We are invited to come along. Nothing we do or say is going to stop them.

That last part is a lesson already learned by the Atlanta Braves and Milwaukee Brewers, and now the Philadelphia Phillies are boning up on this vibe becoming fact. On Saturday, in Game One of the National League Division Series at Citizens Bank Park, the Phillies threw Zack Wheeler at the Mets. The Mets didn’t duck, didn’t scatter, didn’t warn each other “GET OUT OF THE WAY, THERE’S A ZACK WHEELER BEING THROWN AT US!” They stood in calmly against Zack Wheeler (and his ally Andy Fletcher) and withstood as best they could whatever Zack Wheeler threw (and Andy Fletcher called) at them.

And then, like 2024 Mets Magic, Zack Wheeler was gone. This is not to be confused with the offseason after 2019 sorcery that made Wheeler disappear from New York and land a hundred miles south. This was 111 pitches of all Wheeler had in his arsenal, and, boy, did he fire everything he had. There was one Met hit in those seven innings when Zack strode the mound. There were a few bases on balls that didn’t lead anywhere, except to an elevated pitch count. There was nothing on the top line of the CBP scoreboard except for zeroes.

As Saturday stayed Phillies 1 Mets 0 for an uncomfortably long period, my instinct was to recall the two other postseason series in Mets history when the Mets lost, 1-0, in Game One — the 1986 NLCS and 1986 World Series — and comfort myself and anybody with whom I’d be communicating later that those series had dramatic and happy endings. Granted, those were best-of-sevens that are by nature more forgiving of stumbles out of the gate, and, however formidable and/or shady Mike Scott and Bruce Hurst might have been in their day, they’re retired. Wheeler, leading 1-0, was very much in the now.

Until he wasn’t. That’s where the elevated pitch count was no small factor. On the very same date eight years earlier, the Mets were shut for eight innings by Madison Bumgarner, who had expended 106 pitches in keeping the National League Wild Card Game deadlocked at 0-0. Even when it was tied, it felt like we were behind. In the top of the ninth, we learned to spell Conor Gillaspie, and in the bottom of the inning, Bruce Bochy forgot the phone number for the Citi Field visitors’ bullpen. Hell, he let Bumgarner bat for himself once the Giants went up, 3-0, the score it remained once MadBum threw thirteen more pitches the Mets didn’t hit. The San Francisco southpaw had given up four hits and two walks in the course of allowing no runs, but they seemed incidental. Maybe he was the last of what is now an extinct breed. One-game series weren’t very forgiving. You knew if the Mets weren’t getting to Bumgarner, the Mets were done. You also knew the Mets weren’t getting to Bumgarner or getting him off the mound.

You know how some games you’re losing by only one yet it feels like a lot more? This, in Philadelphia, wasn’t one of those games. Wheeler’s sensational, but Bumgarner’s breed has gone the way of the four-pitch intentional walk. You knew Wheeler would make his exit eventually, and you had a hunch the Mets offense might show up once he did. As was the case the the last time the Mets saw Flushing, the sooner, the better, you figured. Zack wasn’t out there to start the eighth. Salvation came into sight once the gate to the Phillie bullpen swung open. They may have some capable relievers out there, but none of them is Zack Wheeler.

But before we get to them, let’s hear it for a couple of capable relievers of our own. Let’s hear it for our starter, too. At first when you heard the name Kodai Senga, as in “Kodai Senga will be starting Game One on Saturday after last pitching in July, his only appearance of 2024,” what you most likely heard yourself say was “HUH?” You’re charging with setting the tone for the series that will determine the Mets’ fate for the rest of the fall a guy who’s been hurt one way or another basically all of this year? Then again, the Mets had been breaking it to you gently that they got this, and that included deciding who’d get the ball where and when, so OK, it’s Senga. Super! He was great last year, he swore he was ready, and the brass believed him.

The next thing you heard was Citizens Bank Park erupting following the third pitch Senga threw. Phillie leadoff savant Kyle Schwarber blasted it 425 feet from home plate. In a band box like The Bank — or, to be fair, any modern stadium — that’s a deposit of a run. Schwarber’s unique talent for leading off games with home runs is a problem for opposing pitchers, but it also means nobody is on base when he hits them. How’s that for a defensive strategy working to a tee?

It turned out Senga was very much ready to face other Phillie hitters. His first innings are usually a little dicey; this one he escaped post-Schwarber. The second was Kodai as usual, getting the Phils in order. And that was it for the ghost forker we hadn’t seen in what felt like an eternity. He wasn’t ghosting us, just adhering to a tight pitch count. Unless Senga feels a twitch, he’ll be part of the Mets’ postseason plans as long as we have them to make. Talk about a timely acquisition.

Still, that left the Mets in need of another pitcher to begin the third, which if you’re a connoisseur of Met bullpens, you were conditioned to apply palm to forehead over. Except with Senga suddenly back, the Mets have no ordinary bullpen. For Game One, it featured David Peterson, last seen closing out Game Three against the Brewers, and four days before that, shutting out the Brewers for seven very necessary innings. Starting pitcher dealing like an ace. Recast fireman nailing down a series clincher. Reborn bulk guy in a newly hatched scheme so sensible it just might work. You might say David Peterson was about to complete the most versatile week in Met pitching history.

Complete it he did: three innings, no runs. That’s eleven innings of shutout ball from Sunday to Saturday, compiled in three distinct roles. Any week in which Tom Seaver or Dwight Gooden pitched twice might have been more spectacular, but I can’t think of any Met pitcher who’s been more effective in such a critical multifaceted manner inside a seven-day span. In this game, lefty Peterson ventured into El Sid territory and did it a touch longer than Fernandez’s legendary two-and-a-third versus the Red Sox in Game Seven.

Peterson was succeeded by a more traditional bullpen choice in the sixth, Reed Garrett. The presumed love child of Rick Reed and Wayne Garrett also maintained the tradition of less-noticed Met postseason heroism, facing six Phillies and blanking every one of them. Through seven, the three Met pitchers had combined to give up nothing since Schwarber did what he was bound to do. What a shame to potentially waste such a fine pitching performance.

Which is what they were about to be saying in the Phillies dugout. Wheeler’s 111th pitch was his last, and in came Jeff Hoffman, the latest in a line of distinguished relievers the Mets have had to surmount if they wanted to get anywhere. Remember Raisel Iglesias? Devin Williams? Hoffman’s not the Phillies’ primary closer, but he did make the All-Star team this summer, the same squad that included Wheeler. Yet not all well-regarded Philadelphia pitchers are created equal. On Saturday, there was Cy Young candidate Wheeler for seven, then there was a collective sigh of relief from the lineup that no longer had to attempt to hit him. Compared to Zack, Jeff Hoffman had to look like a day down the shore.

Hi, Jeff. This batter is Francisco Alvarez. He’s so happy to not have to look at Wheeler anymore that he’s gonna single to left to lead off. You can say bye to Alvy after he reaches first. Harrison Bader is gonna pinch-run for him.

Jeff, this batter is Francisco Lindor. You’ve probably heard of him. The Mets fans who infiltrated The Bank have been chanting M-V-P at him for a reason. You can make him swing and miss at the first two pitches you throw him, but you can’t strike him out. I mean you probably can — you were an All-Star — but not this plate appearance. Our M-V-P is going to foul off your third pitch and then lay off the next four, all out of the zone. Lindor shall take first. Bader shall head to second.

Hey, Jeff, this batter is Mark Vientos. He’s on an upward trajectory this season and postseason. Backtracks in his development a little for a game or two but then discerns what he’s doing wrong and returns to progression. He’s about to progress a liner to left that will score Bader to tie the game. Pity, Zack Wheeler won’t get a win out of his 111 pitches of shutout ball. Don’t feel too bad for him. Zack used to hang out with this guy Jake who told him what it’s like when that sort of thing happens. Anyway, it’s 1-1, Lindor is on third and Vientos took second on the throw that didn’t get Lindor.

That’s three batters, Jeff. Your manager says you can go.

Matt Strahm was next. Another All-Star. The Phillies are loaded with them. They have a couple of stars on their jersey’s wordmark. Good for them on all that. Lindor, East Coast National League MVP, wasn’t an All-Star this year. Nor was Brandon Nimmo, despite having a helluva first half. Seems few outside the Mets sphere fully appreciate Brandon, no matter what he does. Maybe more will now that Nimmo has singled home Lindor to give the Mets a 2-1 lead, pushing Vientos to third.

I’m sorry, I forgot to make a formal introduction. Matt the All-Star, that was Brandon the everyman. Yeah, over on first. That’s him.

Pete Alonso requires no introduction. He’s been all over the highlights since Thursday night. He doesn’t need a most memorable home run here. A fly ball will do nicely. It does. Pete’s sacrifice to center scores Vientos, and it’s 3-1.

Not that this hasn’t been fun, but it’s about to get real fun here, because Jose Iglesias is up next. They won’t play his music (it’s every Mets fan’s music) in Philadelphia, but Jose’s got a new remix coming out. He previewed it against Strahm. “From OMG to Oh and Two to Oh, Just Settle In, Matt.” It starts with a called strike, then a swinging strike, and then the beats per minute kick in. Iglesias fouls off a slider. Then he fouls off a fastball. Then he fouls off a cutter. Then another fastball, another slider, and two more fastballs. When the Grammy nominations for Best Time Up by a Met In a Late Inning Late in the Season or in the Postseason are announced, don’t be surprised to find this one competing with Tyrone Taylor’s dozen-pitch walk from Monday versus the Braves. The Grammy voters love epic PAs and ABs.

So do Mets fans when they end with a single up the middle, as Iglesias’s did. Ten pitches. Nine of them with Strahm ahead in the count. No balls thrown. Real balls shown. Iglesias’s hit didn’t drive anybody in. It merely placed Nimmo on second and Jose on first. But its effect was that of a dagger through the heart of the Phillies’ desire to keep the game from getting out of hand.

Strahm was done after his three-batter minimum; Rob Thomson’s cover charges were creating a lengthy tab. Next to settle in for a trio or more of Met hitters was fireballing Orion Kerkering, announced into the game once Carlos Mendoza opted to pinch-hit J.D. Martinez for Jesse Winker. Kerkering is 23. Martinez is 37. Youth versus experience. Shades of Bob Welch taking on Reggie Jackson. It’s the kind of showdown meant to be savored under the lights of the postseason…except Martinez the veteran isn’t in the mood to linger. He strokes rookie Kerkering’s third pitch into center to score Nimmo and send Iglesias to third. Then Marte, another player who’s Been Around, delivers the fly ball that brings home Brandon.

The Mets, who trailed, 1-0, now led, 5-1. A nailbiter had morphed into not exactly a laugher, but a game that could breathe, and you with it. As long as we’re referencing postseasons past (Octobers tend to get into your head and remain there forever), I found myself recalling Game Two of the 1973 NLCS. That one went 1-0 for eight tense innings, until the Mets exploded for four runs in the top of the ninth. Of course they had the “1” in 1-0 that day, and the pitcher in command, Jon Matlack, wasn’t coming out, no way, no how. He stayed in to finish a 5-0 two-hitter for the ages. Give Yogi Berra credit for occasionally handling his pitching perfectly that month.

This one still needed a little shepherding to the final outs. In the bottom of the eighth, Mendoza called on Phil Maton, and Maton rather than the imposter wearing No. 88 in Milwaukee materialized. Phil struck out Schwarber, struck out Trea Turner, allowed a double to Bryce Harper (into each life a little Bryce must fall), but then grounded out Alec Bohm. The Mets’ ninth saw Bader the erstwhile pinch-runner do some hitting, some stealing and some coming home when Nimmo took the concept of insurance seriously. Like a good neighbor, Brandon is there. The Mets were now up, 6-1, more than enough to keep Mendy from waking Edwin Diaz from his well-deserved nap. True, Diaz did have to stir a bit once Ryne Stanek made the ninth a little longer than it had to be, but Ryne finished the job at 6-2. The Mets beat the Phillies, took the series opener and clarified for all us loyalists who love them no end but doubt them practically constantly that they indeed got this.

If they say so.

Still, I’m gonna be careful to not sit the wrong way or think the wrong thing. It’s the postseason. You can’t be too careful. What was it Yogi advised? “You don’t got this ’til you got this.” But, between you and me and the doubts that probably won’t dissipate until there’s no longer reason to harbor a single one of them in 2024, they got this.

by Greg Prince on 5 October 2024 10:54 am It’s so much easier to give up. The Mets are losing. The Mets are going to lose. I know the Mets are going to lose. You know the Mets are going to lose. So let’s give up on the charade of rooting for them to stop losing and give in to the reality that a loss is nigh. Let’s stop pretending they can possibly win. Maybe it will hurt less if we pivot immediately to acceptance.

That it’s easier to give up then keep hoping doesn’t make the result you’re fully and reasonably expecting any less difficult to swallow. The season is about to end. The postseason is about to end. We’d earned our invitation only the other day, and now we’d have to grab our stuff and get the hell out. The party would go on without us. I hate how it continues to be fun for others in those Octobers we are forced to walk away from it. We can see it through the window, on the outside looking in. What did we even show up for in the first place?

Lose and go home. Sports can make “home” sounds like such a dreadful place.

If I make peace with the impending loss before it goes final, maybe I can say something clever or cynical to give me a moment’s respite from my sorrow. There’s nothing that will lessen the sorrow, but at least I can sound like I know what I’m talking about. I saw this coming. It was obvious. Changes need to be made. I could’ve told you that innings ago. They always do this to us, don’t they?

Your logic fights with your emotion. You understand they don’t always do this to us. The foundation of your rooting life is based on them doing things for us, not to us. You came along at the exact right moment, you tell yourself, when all you knew about the Mets was they won and you heard it was a miracle and you were too young to know it wasn’t the norm. You figured it out soon enough, but you had the miracle, and another almost-as-Amazin’ miracle a few short years later, and, after withstanding a lot of bleakness, a combination of dominance and miracle, where you knew you rooted for the best team in the world and they still did things only a team that found itself completely out of hope had to do to survive — and they did. Whenever somebody remarks at a particular interlude, “they always do this to us,” I think, “I guess you don’t remember or never heard of 1969 or 1973 or 1986.” Your logic fights with your emotion. You understand they don’t always do this to us. The foundation of your rooting life is based on them doing things for us, not to us. You came along at the exact right moment, you tell yourself, when all you knew about the Mets was they won and you heard it was a miracle and you were too young to know it wasn’t the norm. You figured it out soon enough, but you had the miracle, and another almost-as-Amazin’ miracle a few short years later, and, after withstanding a lot of bleakness, a combination of dominance and miracle, where you knew you rooted for the best team in the world and they still did things only a team that found itself completely out of hope had to do to survive — and they did. Whenever somebody remarks at a particular interlude, “they always do this to us,” I think, “I guess you don’t remember or never heard of 1969 or 1973 or 1986.”

I also think, “Those are not recent examples.” I have others from later years, but the endings never quite make the point I wish them to. It was great while it lasted in 1988, 1999, 2000, 2006, 2015, 2016, and 2022, but go find a flag that fully satisfies. Besides, now we’re into fine points. The Mets are doing what they “always” do to us, and you’re kind of buying in.

What a ride to emerge in a playoff race. What a ride to keep racing. What a ride to pass who needed to be passed on the very last day. What a shock to be not so shocked that we’re in this postseason. It’s the Dayton portion of the tournament, but it counts. They make t-shirts for this. We won the first game. We didn’t hold on to the second game. We’re toe to toe, zero to zero, in the third game…until we aren’t.

And the only logical conclusion my emotion comes to is this would be a good time to give up. Not yet in the seventh. Not really in the eighth. But in the top of the ninth, logic and emotion stage an intervention and tell me it’s about to be over. Francisco Lindor, most valuable everything, works — and I mean works — a walk, because the man who saved the season on Monday isn’t going to help euthanize it on Thursday. He could have, I suppose. Keith Hernandez made the second out of the tenth inning of Game Six. Nobody’s beyond making an out. But Lindor didn’t.

Still, with one on and one out, Mark Vientos, who’s not Francisco Lindor (who is?), goes about striking out, and it hits me that I need to know what time it is. Every year when a Met season is about to end, I keep an eye on the clock so I can mark the time of departure from the season we’ve been living in. Come late December, I’ll take that data point and the announced first-pitch time for the next Opening Day and calculate the Baseball Equinox, that moment equidistant between Met seasons. It’s intended as a warming spot for the dead of winter, but it’s also very much a product of winter. Winter, I’d deduced, was coming as Vientos struck out.

Kept clicking the side of my phone. 9:43. 9:45. Somewhere in there Brandon Nimmo is up and fouling off pitches to dig an oh-and-two hole. Clicking the phone. Seeing the time. This is how I will ease myself into winter on October 3, 2024. What a task I have chosen for myself as the Mets get set to go away.

Then Nimmo singles and Lindor is on third and Alonso is up, which is just swell, because heading into the top of the ninth, I muttered in my head that this season would find a way to end either with Alonso on deck or Alonso making the last out. Not believing in Alonso was also easier than sticking with him. It wasn’t any less painful.

Pete got the count against All-Star closer Devin Williams to three-and-one, and I allowed myself to think maybe he could work a walk, load the bases, pass the baton, build a rally that would…I didn’t know if a rally was going to do any good, but it was better than making constant time checks.

He swings at the next pitch, and my first instinct is to be sorry he hasn’t walked. I hear Howie Rose begin to describe the fly ball Pete has launched before I ever see it, because the radio behind me is about twenty seconds ahead of the muted TV in front of me. The TV essentially exists in Game Three for replays. Howie isn’t telling me anything that indicates Pete made a bad decision to swing. The ball is gone. The Mets, down 2-0 since the seventh, are ahead, 3-2. Simultaneously, I let out a piercing scream, hug my wife, and worry aloud that The Game Is Not Over. This may have been dramatic and necessary and, as Howie called it in the moment, “memorable” (though that’s usually something we can confirm months and years later when it’s not presently going on), but it’s not yet definitive. The Mets lead by one in the ninth. The night before, the Mets led by two in the eighth. I’ve spent too much of the past two innings descending into a state of not believing to suddenly do a 180. At most, I’ve turned 135 degrees toward optimism. But, c’mon Mets, add another run. He swings at the next pitch, and my first instinct is to be sorry he hasn’t walked. I hear Howie Rose begin to describe the fly ball Pete has launched before I ever see it, because the radio behind me is about twenty seconds ahead of the muted TV in front of me. The TV essentially exists in Game Three for replays. Howie isn’t telling me anything that indicates Pete made a bad decision to swing. The ball is gone. The Mets, down 2-0 since the seventh, are ahead, 3-2. Simultaneously, I let out a piercing scream, hug my wife, and worry aloud that The Game Is Not Over. This may have been dramatic and necessary and, as Howie called it in the moment, “memorable” (though that’s usually something we can confirm months and years later when it’s not presently going on), but it’s not yet definitive. The Mets lead by one in the ninth. The night before, the Mets led by two in the eighth. I’ve spent too much of the past two innings descending into a state of not believing to suddenly do a 180. At most, I’ve turned 135 degrees toward optimism. But, c’mon Mets, add another run.

Here came Jesse Winker and here came Starling Marte, and we had a tack-on run, and it was Mets 4 Brewers 2, and like Jose Quintana going six scoreless and Edwin Diaz somehow making everything stressful for an inning-and-two-thirds but not giving up a single run, it is huge. As huge as Lindor’s walk. As huge as Nimmo’s single. Maybe not as huge as Alonso’s homer, because we all know Alonso’s homer will be memorable, especially if the Mets win. They haven’t won yet. All kinds of Mets did all kinds of memorable things to get to and succeed in the seven postseasons spanning 1988 to 2022, but most of their memorability exists in the shadow of they always do this to us.

Also, because it’s October 3, the 4-2 score gnaws at me. The Dodgers led the Giants 4-2 on October 3, 1951, when Bobby Thomson came to bat with two men on in the bottom of the ninth at the Polo Grounds. The legend of what Bobby Thomson did next played a large role in making me a retroactive New York Giants fan. I did not want karmic payback from the ghost of Ralph Branca via a Coogan’s Bluff score of Brewers 5 Mets 4.

(Isn’t it astounding how much can go through your mind between innings and pitches?)

But we are winning. And David Peterson, starting pitcher, is coming on in relief in the bottom of the ninth, because Edwin Diaz is only human. Odd, I pause to consider, that we carried 13 pitchers into a three-game series in which we knew we’d use three starting pitchers, meaning we had nine relievers by trade plus one potentially superfluous starter, and it’s the starter who’s now taking on the most enormous bullpen assignment of 2024. I’m not arguing Peterson wasn’t the right choice. Among those Met relief pitchers who were presumably rested and conceivably ready, I wanted to see exactly none of them attempt to protect a two-run lead in this ballpark against this opponent. I’ve seen David Peterson pitch many effective innings this year. Just pitch one here.

He did, of course. He gave up a leadoff hit, but then struck out the next Brewer and induced a double play ball, more specifically a ball that transformed into double play material once it reached the glove of Francisco Lindor, the guy who’d been weaving wonder all week. He dashed from short to second, stepped on the bag, and threw that ball to the other weaver of wonder, Alonso. Mets 4 Brewers 2, October 3 still a helluva date.

I have absolutely no idea what time the last out was recorded, because it doesn’t matter. Winter was immediately postponed for the duration of the National League Division Series, which starts this afternoon in Philadelphia, Kodai Senga shocking the stuffing out of everybody by going for New York, Zack Wheeler no longer surprising anybody by looming in Phillies red. It’s a best-of-five, meaning no matter what happens across this weekend, postseason baseball will be played this coming week at Citi Field when the Mets and the series come home.

Sports can make “home” sound like such a beautiful place, too.

There is no question of believing or not believing this Saturday. The emotional clock has reset. I shall only believe from here on out, certainly until the next time I begin to give up. Hopefully that will be in some other year. Hopefully is how I will try do everything for however long this ride continues. There is no question of believing or not believing this Saturday. The emotional clock has reset. I shall only believe from here on out, certainly until the next time I begin to give up. Hopefully that will be in some other year. Hopefully is how I will try do everything for however long this ride continues.

by Jason Fry on 4 October 2024 1:16 am More than once this year, I’ve thought to myself that Pete Alonso would probably be more of a hitter if he were less of a teammate.

But Alonso isn’t capable of that. He cares about his teammates, about the only organization he’s ever known, and yes, about us lunatics in the stands. He wants to come through for all of us, so much that he puts too much on his shoulders. We’ve all seen the results: tentative ABs turning into overaggressive ones, or fly balls that are harmless because he tried to hit one to the moon when one three-millionth of that distance would have sufficed.

I’ve worried about that in the last few weeks, but I’ve also noticed some other things. I noticed that Alonso had become Francisco Lindor‘s best friend at first, scooping balls out of the dirt with Lindor’s compromised back affecting his throws. And I noticed that Alonso mostly wasn’t falling prey to those I ALONE CAN FIX IT ABs that ambush him from time to time. He was working good counts and refusing to fish for balls he couldn’t do anything with.

He wasn’t being rewarded with big hits, but I saw enough that I kept hoping.

And I hoped for something more: that maybe Alonso, in watching the heroics of Lindor and Jose Iglesias and Luisangel Acuna and so many other teammates, would internalize something he’s always known intellectually but never seemed to quite accept emotionally: that he is not in fact alone, that he is a critical piece but still part of a collective whole, that teammates will pick him up if he fails and trust him to do the same.

Sit with that a moment; we’ll come back to it.

Most of Thursday night’s winner-take-all showdown in Milwaukee was an agony of misfires. The Mets couldn’t scratch against Tobias Myers, whose four-seamer had the kind of movement that kept them just missing balls — I lost count of the number of balls that looked good off the bat only to die in outfielders’ gloves. Myers pitched five innings and all of two Mets reached base: Lindor doubled to lead off the game and later singled, and Milwaukee fan favorite Jesse Winker got hit with a pitch.

Fortunately, Jose Quintana equaled Myers. Quintana didn’t look great early, dealing with a lot of traffic, but as the game went on he saw that the Brewers were chasing more than they usually do, and so started tormenting them with changeups in the dirt and fastballs off the plate.

It was a gutty, canny performance, one I appreciated even more because Quintana’s 2024 taught me an important lesson: Don’t be so quick to write guys off. Back when things looked dire I disparaged Quintana (and some of his mound mates) as a feckless nibbler; when he went through a rough stretch in early August I would gladly have driven him to the airport myself if it meant we could be rid of him.

That wasn’t fair for any number of reasons, but two important ones are that I paid no heed to how much pride Quintana takes in his craft, or to how much work Jeremy Hefner and the Mets braintrust put into monitoring their pitchers, figuring out what’s working and what isn’t, and being patient as guys figure out adjustments. That’s been true of Quintana, of Sean Manaea, of David Peterson, of Tylor Megill, of Ryne Stanek — to say nothing of the nightly drama around Edwin Diaz, his mechanics and his psyche.

Quintana kept the Mets in it and handed the ball over to Jose Butto, who’s made strides as a pitcher but is still in the blurry space between roles: no longer a starter (at least for now) but not yet truly a reliever. Butto needs more time between appearances than a typical setup guy, and given the crazy rollercoaster ride of the last week more time hasn’t been available. He entered a scoreless game in the seventh and on two pitches put the Mets in a 2-0 hole: Jake Bauers clobbered a changeup sitting in the middle of the plate and Sal Frelick took a four-seamer over the fence.

Diaz got the Mets out of the inning without allowing anything else, though he didn’t exactly look crisp himself, and the Mets could do nothing against Freddy Peralta, pressed into service as a bridge to Devin Williams.

Had I given up when Williams took the mound? I hadn’t — partially out of stubbornness but also because this edition of the Mets had engineered crazier escapes. The key, I kept thinking to myself, was Lindor: He had to find a way to get on base. Fortunately, he was the player I trusted most to do it.

And after that? That’s where my belief got a lot shakier. But I knew Mark Vientos had power, and he’d seen his share of big moments. Hadn’t Brandon Nimmo hit a mammoth home run off Raisel Iglesias just a couple of Met fan heart attacks ago? And then there was Alonso, whom no ballpark can hold if he gets a hold of one.

I figured the most likely outcome was Lindor reaching first, or maybe second, and the season ending with a last shot of him disconsolate amid blue and yellow celebrants. But I also kept telling myself that wasn’t the only possible outcome.

Lindor’s leadoff AB against Williams a clinic from a player who knew exactly what had to be accomplished and was bending every ounce of his will to the task. Williams got to 1-2 using the formula that’s been so successful for him: that intimidating four-seam fastball up and that deadly changeup down, so a hitter has to be geared up to simultaneously cover the top and bottom of the strike zone and negotiate a 10 MPH difference in speed. Lindor refused to expand the strike zone, fighting back to 3-2, fought off a pair of four-seamers that had the plate, then looked at one outside for the walk.

That brought up Vientos, who had no chance against the four-seamer after being tantalized with a trio of changeups. (Hey, it happens — guys don’t roll to a 1.25 ERA by accident.) Williams tried the same program against Nimmo, but the third changeup got too much plate on 0-2 and Nimmo smacked it into right field for a single.

And so up came Pete.

The first pitch was a changeup down the middle, and it looked like Alonso’s knees sagged a bit. Don’t help him! I entreated the Polar Bear from 700-odd miles away. And Alonso didn’t — he spat on two four-seamers at the top of the zone as well as a changeup in on his hands. None of them was a pitch he could have done anything with — two pop-ups in waiting and a grounder. That was good; so was seeing Alonso have the kind of AB I’d kept noticing of late, albeit with little to show for it.

Maybe this time would be different. Ya gotta believe, right?

Don’t help him! I said again, unheard as always.

Williams threw another changeup, toward the outer edge of the plate but getting a fair bit of it, and Alonso connected.

This wasn’t one of those majestic shots pulled and headed for orbit. It was an opposite-field line drive. Did I think the ball was going out? Honestly, I was too disoriented and scared to be able to make a judgment like that. It was struck well and in flight, but Frelick was out there and I registered that the outfield fence had a little jog in it, and suddenly there were too many possibilities to catalog: into Frelick’s glove through a cruel quirk of the dimensions, over his glove and off the wall and what kind of jump did Lindor and Nimmo get …

… or, just maybe, over the fence.

Alonso made a chef’s kiss gesture and ran around the bases to be greeted by a conga line of happy Mets. Whatever Insurance It Is Field fell into a shocked hush; at the Citi Field watch party popcorn was flying and strangers were jumping and hugging; at the Playwright up in Midtown, the 7 Line was a screaming blizzard of orange and blue. And in a living room in Brooklyn Heights, I was jumping up and down like a maniac screaming and scaring the neighbors.

Here, for posterity, is Howie Rose’s call:

Here’s the pitch … swing and a fly ball to right field, pretty well hit. Frelick back, at the wall, he jumps — and it’s GONE! HE DID IT! HE DID IT! PETE ALONSO WITH THE MOST MEMORABLE HOME RUN OF HIS CAREER! PUMPS HIS FIST AS HE ROUNDS SECOND! IT’S A THREE-RUN HOMER! HE’S GIVEN THE METS A THREE TO TWO LEAD! THEY ALL POUR OUT OF THE DUGOUT! ALONSO ON HIS WAY TO HOME PLATE, THEY’RE WAITING FOR HIM! HE HITS THE PLATE, HE’S FIRST CONGRATULATED BY NIMMO! HUGGED BY LINDOR! THERE ARE A DOZEN METS WAITING FOR HIM OUTSIDE THE DUGOUT! PETE ALONSO KEEPS THIS FAIRY-TALE SEASON GOING WITH THE FAIRY-TALE SWING OF HIS CAREER! THREE TO TWO NEW YORK!

And then, almost immediately, I had a terrifying thought: Who’s going to close?

Fortunately, the Mets weren’t done. After Iglesias grounded out, Winker was hit by another pitch and then stole second, bad back and all. Williams went back to that pattern again against Starling Marte: three changeups, then a four-seamer. Marte spanked the four-seamer over first to bring in Winker, and that was it for Williams: He’d given up four runs, one more than he’d surrendered in the regular season. And an opposite-field homer? No one had ever hit one of those off Williams.

That extra run loomed large as Peterson (there’s your answer) immediately gave up a sharp single to Frelick. He struck out Joey Ortiz, but that brought up Brice Turang, the speed merchant who’s tortured the Mets for more than a week now.

So of course, because baseball is nothing if not utterly perverse, Turang smacked a grounder right at Lindor, hard enough that not even Turang’s terrifyingly fast wheels could deliver him to first before the ball thudded into Alonso’s mitt for the back end of a game-ending double play.

Amazin’, one might say. Or even Oh My God.

Everything goes by so fast. Blink your eyes and Alonso and Lindor will have become visiting dignitaries, interviewed during sleepy midsummer innings by some future Steve Gelbs. You’ll marvel at the fact that they’ve grown gray and try not to think about your own journey along that road.

But these days will be remembered. Twice in a week, the Mets have delivered games that you’ll see revisited during innumerable rain delays, ones that you’ll find yourself smiling to recall at odd moments years and years from now.

These are the games that transmute heartbreak into giddy triumph, that keep us coming back for all the nights enemy closers don’t crumble and opposing outfielders leap a little higher. When you get one of these, you cradle it and give thanks for it. Because these are the games that keep that stubborn little ember of belief burning, awaiting the joyous ignition that’s the reward of being a fan.

by Greg Prince on 3 October 2024 1:37 am I had the feeling I was seeing something I hadn’t witnessed before, so I ran through it in my head to confirm. Eleven postseasons. Twenty postseason rounds. Ninety-four postseason games. It took until the respective eleventh, twentieth and ninety-fourth of the above for the New York Mets to do something they’d never done before. Never before had the Mets been as few as six outs from clinching in a playoff situation without, in fact, clinching.

Not the history we were seeking Wednesday night in Milwaukee.

A Wild Card Series sweep was close enough to taste, distant enough that you couldn’t really get a grip on the fork you wished to use for the tasting. Yes, we were up a run with two defensive innings to go. No, it wasn’t a case of fait accompli interruptus. Six outs against a ballclub like the Brewers is simply too many to count down if you’re planning to drape plastic sheeting over the clubhouse stalls with confidence. The first three outs the Mets had to get ended up intertwined with three Brewer runs. There wouldn’t be anymore defensive outs after that.

Oh, that eighth inning. Oof. Honestly, though, you could say “oof” to a good bit of Game Two before Phil Maton gave up the two home runs that turned the tide for, one hopes, one night and not the entire series. “Oof” watching Sean Manaea struggle a little more than usual through five (though his bottom line of just two runs wasn’t too bad). “Oof” watching Pete Alonso tangle his feet in his bat as he sought to beat out a potential double play, which seemed possible on this particular first-inning, one-out grounder — with Mark Vientos on third — until Pete failed to appear in our picture. The Polar Bear hit the ball, dropped his lumber, tripped over it, and so much for dashing down the line in time for Vientos to score. The Mets had put one on the board. More right away would have been nice.

“Oof” repeated itself often, as the Mets singled eight times, only to leave nine runners on base while going 2-for-11 with runners in scoring position and producing nary a double, triple or homer. Pete plopping to the dirt notwithstanding, they actually looked pretty swift getting to first, second and/or third on several occasions. It was the not bringing any of those runners home after the second inning that doomed them.

That and Phil Maton, I suppose. Manaea did all he could across 86 pitches, and I was OK with limiting him to five innings. Reed Garrett and Ryne Stanek held the 3-2 fort in the sixth and seventh. Maton, the second-half godsend who didn’t have it in Atlanta, didn’t suddenly rediscover it in Milwaukee. Jackson Chourio, who led off the game with a homer, smoked Maton ASAP to knot the score at three. Phil gave up a single to Blake Perkins directly thereafter, but a crisp double play (we did execute some sweet defense) erased him. Howie Rose and Keith Raad were barely done confirming that, should it be relevant, ghost runners don’t materialize in extra innings in the postseason — I’d muted ESPN — when Willy Adames singled and Garrett Mitchell made the subject of extras moot. Mitchell’s two-run homer put the Brewers up, 5-3, and you sensed the Mets would not be upending Devin Williams’s apple cart in the ninth. They didn’t.

I resisted taking my own calculation of “six more outs” too seriously when we got through the seventh. I didn’t necessarily know Maton was gonna come in, but I didn’t have a good feeling about him. After riding the runaway train known as Edwin Diaz on Sunday and Monday, I didn’t have a good feeling about him for Wednesday, either. Against the runnin’ Brew Crew, I didn’t want to see Adam Ottavino. No starter was available to step in. Max Kranick’s on the roster, but this would have been quite a spot for a Met debut. Overall, I had no idea how the Mets were going to get the six outs that would have put them in the Division Series.

More runs would have been great. Some games yearn to be won with offense. Winning with offense got us into this postseason, you might recall. We pierced but didn’t bludgeon starter Frankie Montas, and nudged rather than bulldozed various Milwaukee relievers. We nursed a one-run lead when we should have building a much larger version. The construction materials were right there on base.

The good news — besides a brand new blank scoreboard greeting us for Game Three, and Jose Quintana being rested enough to conceivably fill it with zeroes — is there is a touch of precedent on our side to effect the ultimate desired outcome despite what occurred to ruin Game Two. We were eight outs from clinching the NLCS in 1973, when the Reds tied Game Four at Shea on Tony Perez’s seventh-inning home run off George Stone and went on to win after Pete Rose homered in the twelfth. Things worked out OK in decisive Game Five the next day behind, among others, Tom Seaver, Tug McGraw and Willie Mays (sometimes all it takes is a few immortals). And in 2015, the Mets had an opportunity to clinch the NLDS when they were up two games to one on the Dodgers, but didn’t take care of business against Clayton Kershaw at Citi Field. They never led or inspired much hope that they’d capture Game Four nine years ago. Instead, they saved their big finish for winner-take-all Game Five in L.A., where Jacob deGrom, Noah Syndergaard, Jeurys Familia, Curtis Granderson, Travis d’Arnaud and, most of all, Daniel Murphy conjured a 3-2 win to secure the series.

None of those guys is on this team right now, but this team and the guys we do have have brought us further than any of us dared dream they could when the season was young…hell, when the season was middle-aged. One more night awaits, one that could unlock more. Let’s root for that, shall we?

by Jason Fry on 2 October 2024 6:57 am It was the ninth inning against the Phillies, 10 days ago, and ESPN’s little win probability thing (a sop to gamblers, but that’s another post) was making me insane.

It said the Phillies had an 8% chance of coming back to beat the Mets, which was obviously wrong. Obviously and deliberately and nefariously wrong. I didn’t know the Phillies’ win probability — how would you even calculate that? — but I knew mischance and misfortune, and it seemed far more likely that the Phillies’ win probability was around 80%, with the only question the nature of the disaster waiting in ambush.

Instead the Mets won. I was no longer paying close attention but I assume the win probability thing ticked to 100% before being ushered out of view.

After the Mets claimed Game 1 of their Monday special against the Braves, punching their postseason ticket in what may well have been the best regular-season game in club history (now there’s an offseason post/series to look forward to), I took advantage of Game 2’s vacation from anxieties to pore over the game thread on Battery Power, the SB Nation blog that’s the Braves equivalent of our beloved Amazin’ Avenue. I wanted a real-time record of Braves fans being imperious before being brought low, and to see their assumption of doom for the Mets get forcibly and delightfully corrected.

But that wasn’t what I found. Instead, to my surprise, I found a hairball of angst, one that snarled up long before Tyrone Taylor Shawon’ed Spencer Schwellenbach out of the game: Matt Olson couldn’t hit, Marcell Ozuna would never hit again, Travis d’Arnaud only ever grounds out, Brian Snitker always leaves his starters in too long, Joe Jimenez is reliably terrible, and on and on and on.

Press a Met fan into service as a TV meteorologist and she’ll stand in front of the map with a dozen variations on black clouds and lightning bolts and maybe one wanly yellow little sun, which she’ll bashfully keep behind her back. That’s our reputation as a fanbase, and it’s one we haven’t exactly run from — if anything, we’ve run toward it when things have gone wrong or look like they might go wrong or we assume they’ll go wrong because things have gone wrong before.

But it turns out every team’s fanbase does this. (Twitter is now 1/3 conspiracy loons, 1/3 Bitcoin grifters and 1/3 Yankee fans calling for the head of Aaron Boone.) We all think our lineup is made up of ticking time bombs, our franchise is run by dimwits and/or saboteurs, and our win probability is actually around a tenth of whatever the gamblers are being told.

I was scowling at that win probability thing again Tuesday night, as the Mets came back to Milwaukee to take on the Brewers at the what the fuck is this shit time of 5:30 pm.

The Brewers who’d rather idly taken two out of three from a weirdly tight post-rainouts Mets team not very long ago.

The Brewers of Brice Turang and Jackson Chourio and Garrett Mitchell and other guys whose features I’m not familiar with because I’ve mostly only registered them as blurs stealing second and then zipping home.

The Brewers of Rhys Hoskins, because of course.

The Mets fell behind 2-0 against those Brewers in the bottom of the first, as some plays you’d like to see made weren’t and Luis Severino reported for duty missing his location and a reliable putaway pitch. It was 2-0, and clearly our win probability was 0.00000000%.

Except the Mets leapt off the mat in the top of the second: Mark Vientos singled (he had terrific ABs all night), Pete Alonso walked and up came Jesse Winker, who’d been mired in a deep slump and waylaid by back issues of his own. Winker saw eight pitches from Freddy Peralta, whistling the eighth into the right-field corner to tie the game and take himself to third with a triple, and if you had JESSE WINKER TWO-RUN TRIPLE on your bingo card, well, my cap is tipped. He came home on a sac fly from Starling Marte, another Met who quietly put together a night of solid ABs, and just like that the Mets led 3-2.

But once again, Severino didn’t look right. He worked through traffic in the second and third, then gave back the lead in the fourth, with the inevitable Turang front and center at the Brewer raceway. (Remember when Milwaukee lineups were made up of one scrawny infielder and eight dudes who looked like Daniel Vogelbach, including the actual Daniel Vogelbach for a time? I liked that better.) The Mets were down a run (win probability 0.0000000%) and Milwaukee’s Pat Mitchell decided that was enough from Peralta, dipping into his formidable bullpen and summoning Joel Payamps.

It didn’t work. Payamps got Marte when Chourio made a leaping grab at the fence, allowed a double to Taylor on a ball Chourio misplayed, retired Francisco Alvarez for the second out, but then lost Francisco Lindor on a walk. Up came Jose Iglesias, who smacked a ball left of first that Hoskins made a good play on, only to find Payamps a little tardy getting to first. Iglesias dove in head-first, one of the few times that play makes sense, just beating Payamps while the always-alert Taylor motored around third to tie the game.

In came Aaron Ashby, who allowed an infield single to Brandon Nimmo and then boom: a two-run single for Vientos, followed by another one from J.D. Martinez, pinch-hitting for Winker.

Just like that the Mets led 8-4, and the ballgame was over. No really, it pretty much was. Severino found a little tweak that corraled his fastball — or perhaps he started pitching like he had a four-run lead and eight guys behind him — and so set down Brewer after Brewer before passing the baton to Jose Butto, who in turn handed it to Ryne Stanek.

No Brewer reached base against the three of them, and no Met tallied a hit against Nick Mears or Aaron Civale. Four and a half innings ticked by in a stately procession of round trips between dugouts, with the lone baserunner accounted for by a walk to Alonso. An October playoff game became one of those sleepy late June affairs in which you pick up a magazine and it winds up as a tent over your face during a baseball nap.

Which, given the emotional toll of the last week and change, wasn’t unwelcome. Eventually Stanek struck out Turang, Alvarez didn’t allow a dropped third strike, it turns out there’s no heretofore-overlooked rule that allows Turang to circle the bases five times while Met catchers fail to throw him out, and so that was that.

Win probability 100%. Be not afraid.

by Greg Prince on 1 October 2024 4:35 am Late on a Sunday night in 1975, I’m watching Sammy & Company on Channel 4 because I’m up, it’s on, and nothing else is. The Sammy in question is Sammy Davis, Jr. He’s done it all in show business and now he’s hosting this syndicated not quite talk show, not quite variety show. It’s got Sammy and he’s got company. That’s enough in the pre-cable days to keep a 12-year-old insomniac tuned in. On this episode I’m recalling, Sammy’s doing a number from a Broadway musical he was in a dozen years earlier, a show called Golden Boy. I’d never heard of Golden Boy until the moment he told us he was about to perform a song from it. The song, “This Is The Life,” makes an impression on me because one line grabs my attention:

Polaroid pictures, stereo sets, season box to see the Mets

Twenty-five years before I began keeping a file of Met mentions in the popular culture for my own edification and thirty-seven years before the first edition of Oscar’s Caps saw light, I made a mental note of that there’s a song in a show that starred Sammy Davis and it has the Mets in it.

That information settled in the recesses of my brain, of no consequence in my life until September 1999, when, with the Mets bearing down on a playoff spot, “season box to see the Mets” bubbled to the surface of my 36-year-old consciousness, and I decided I needed to hear this song and have this song. Nascent file sharing and the application of something called MP3s surpassed my understanding. If I wanted a song, I bought the CD. I worked not far from a Barnes & Noble in Manhattan, a store whose soundtrack collection brimmed with the best of Broadway going back years. Yes, Golden Boy was there. Yes, I purchased it. Yes, I played “This Is The Life” quite often in the fall of 1999, a period when anything Metsian was welcome in my ears. I don’t think I gave the rest of the album more than a perfunctory listen.

In March of 2002, City Center’s Encores! series staged a concert version of Golden Boy. Hey, I more or less said to my wife, that’s the show with “season box to see the Mets” in it. We had seen and greatly enjoyed the very first Encores! production in 1994 (Fiorello!) but let our initial subscription wane. This seemed like a good excuse to return to the grand old theater on 55th Street. Alfonso Ribiero, Carlton from The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, played Davis’s role. I was delighted to hear “This Is The Life” live and became aware of the rest of the soundtrack.

A couple of weeks later, the baseball season began, a season I was more in tune with than the Broadway season. The Mets’ first tour…I mean road trip took them to Atlanta. You know, Turner Field. This was April 2002. For five seasons the Mets had been visiting this facility and leaving it to scathing reviews. Actually, I suppose the Atlanta crowd applauded the Mets taking their bows there because it usually meant showstoppers from the Braves. Ever since September 1997, the Braves had been stopping the Mets’ show, crushing their hopes autumn after autumn. The Mets had never finished ahead of the Braves since Atlanta moved to the NL East. The Mets never definitively defeated the Braves when it absolutely mattered, especially in Georgia.

But this year, I told myself at 39, was going to be different. We’d just come through the offseason of Alomar and Vaughn, the reacquisitions of Cedeño and Burnitz. We were remade to finally get over that big, bad, Brave hump. On our first trip in, we took two out of three at the Ted, including one stunner when we scored nine in the ninth to not only break but smash a tie. We won that one, 11-2. A little over a week later, the Braves were up at Shea and jumped ahead, 6-1, by the third. Yet we scored five in the bottom of the seventh, forced extra innings, and, in the twelfth, my favorite position player ever, Edgardo Alfonzo, drove in Jay Payton with the winning run. Mets 7 Braves 6 on the scoreboard. Mets two-and-a-half-games ahead of the Braves in the standings. And resonating in my head, from the song I gained a new appreciation of at City Center during Spring Training, were lyrics I was convinced spoke to the moment at hand.

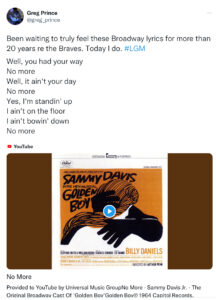

Well, you had your way

No more

Well, it ain’t your day

No more

Yes, I’m standin’ up

I ain’t on the floor

I ain’t bowin’ down

No more

This was my theme song for the 2002 I envisioned taking shape that April. It went on my stereo set and on my next compilation (or mix) tape and I played it clear to…

May, I guess. By June, the shape of 2002 had sagged. The Braves did what the Braves always did. They took over first place and won the division title. They didn’t break the Mets’ heart in September or October of 2002, because the 2002 Mets had no heart left come summer’s end. They finished last, 26½ games behind Atlanta.

So much for “No More”.