The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 3 August 2023 12:41 pm The Original Mets were stocked primarily by a legendarily threadbare expansion draft that left the Mets capable of winning one of every four games they’d play in their first year. With a full season’s experience under their collective belt, the Slightly Less Original Mets took the field for their second year and won eleven more times while losing on nine fewer occasions. From 1962 to 1963, the club’s improvement was glacial, but at least all rainouts were made up and pesky ties were averted.

Not good enough for what even the miserly National League would call progress. Sporting gentlemen that they were, the owners of the eight established clubs deigned to conduct a “special draft” for the benefit of both the Mets and their expansion counterpart Houston Colt .45s. The Colt .45s posted consecutive 96-loss seasons, an introduction which must have struck the 91-231 Mets as aspirational, but couldn’t be considered by any barometer other than comparison to what was going on in New York successful. Every existing pre-’62 team made available at least four players that the Mets or Colts could have for the low, low price of $30,000 each; the generous Reds put five guys up for grabs. Holding drafts was a handy way to shake loose unwanted personnel from your organization, and taking money from newbies was always welcome.

In October of 1961, the Mets and the Colts had no choice but to play along. In October of 1963, toughened by two years of getting beaten up by their elders, the junior franchises mostly said thanks, but no thanks. All of three players went in the special draft. The Mets, winning the coin toss, chose first and selected first base prospect Bill Haas from the Dodgers. In the Daily News, Dick Young judged Haas “the exciting pick,” in that “at least nothing is known of him, and he has a distinction uncommon” among those left by the curb for the taking: “He has not failed in the majors. He has not had the chance yet.”

Nor would he get that opportunity with the Mets. Twenty-year-old Haas, despite having blasted 57 homers out west in various Dodger outposts across two minor league campaigns and being a “big one” in terms of build, would not bust out in the Met system and would never see the majors. Houston’s lone selection already had. He was Claude Raymond, a reliever with ample experience as a Milwaukee Brave reliever. As usual, the Colts outlucked the Mets, with Raymond emerging as pretty darn effective for four seasons in Texas, peaking in 1966 by collecting 16 unofficial saves — they weren’t a recognized stat until ’69 — and making the All-Star team for the renamed Astros. The Braves, having moved to Atlanta and learned their lesson, traded for Raymond in 1967, holding onto him for two years until they could do him the favor of his life and send him to yet another new National League team, the Montreal Expos. The Expos’ 1969 record of 52-110 was of a piece with those the Mets and Colts put up in 1962, but what did Claude care? He was from Quebec, and he was pitching in the province where no other player naturally spoke the same language as the home team’s fans (though Le Grand Orange, Rusty Staub, made it his business to eventually learn French). Raymond would remain associated with the franchise, as a broadcaster and coach, almost without interruption until there ceased to be Montreal Expos in 2004.

Even the Sporting News couldn’t feign excitement, and it was the Bible of Baseball. The final pick of the 1963 special draft, made by the Mets, didn’t have quite the same bilingual ramifications, but all told, it worked out pretty well. The Mets plucked five-year veteran Jack Fisher from the Giants, who themselves had traded with the Orioles to get him a year earlier. His claim to fame to that point was surrendering Roger Maris’s 60th home run of 1961. Wes Westrum, who had just been hired away from San Francisco to assist Casey Stengel, vouched for the 24-year-old selectee: “Fisher can be a good pitcher,” which in 1963, passed for a trustworthy scouting report. By April, Fisher was throwing the very first pitch in Shea Stadium history, “a strike on the outside corner” to the Pirates’ Dick Schofield, per Bob Murphy. In 1965, Jack started 36 games, still the franchise record for a single year. Tom Seaver tied the mark three times; unless you have the scoop on trends in starting pitcher usage reversing themselves, nobody will ever surpass the Fisher standard. The robust righty logged more than 900 innings in four seasons, piling up more than his share of losses (a Met pitcher’s occupational hazard for the bulk of the 1960s) and then was packaged with Tommy Davis to acquire Tommie Agee and Al Weis from the White Sox.

Given Agee’s and Weis’s respective contributions to capturing the 1969 world championship, credit George Weiss for playing the long game with the 1963 special draft. At the time, however, the Mets’ president wasn’t impressed with the entire enterprise. “The other names” on the list, Weiss judged, “were not any considerable improvement over what we have. They are not worth using up roster spaces that might better be used in the regular draft, and in trades this winter.” If you can’t offer up talent superior to that a 51-111 ballclub already claims, there might not be much point to tossing any more coins.

That was the last time any league conducted a roster enhancement exercise specifically intended to bolster Met personnel until the other day. The 2023 trade deadline wasn’t billed as a special draft and it wasn’t sanctioned solely or even partly for the betterment of the Metropolitan Baseball Club of New York, Inc., but you look at the results, and it’s hard to not think we just witnessed the Steve Cohen Supplemental Draft.

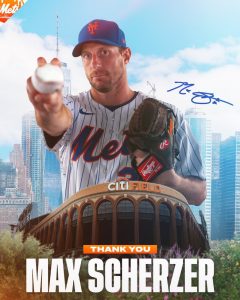

This one was for the Mets, and nobody else, not even Houston. Well, the Houstons were involved, as were their cross-state rivals in Arlington. You could include the operations in Miami, Milwaukee, Phoenix and Anaheim in the equation as well, though the Mets’ business with the organizations based in those places seemed fairly usual for this time of year: a guy not in long-term Met plans exchanged for a kid or more who may very well be soon enough. This is not to dismiss who we got for David Robertson, mensch among men Mark Canha, Tommy Pham or Dominic Leone (or what each individual gave us), but it was trading Justin Verlander to the Astros three days after trading Max Scherzer to the Rangers that made this a special draft. This was the draft with an entry fee only Cohen’s cash considerations could have covered once he nodded “uh-huh” to picking up so many millions of what is owed Scherzer and Verlander despite neither Max nor Justin any longer pitching for the Mets. Prices have gone up since 1963.

The names Marco Vargas, Ronald Hernandez, Luisangel Acuña, Justin Jarvis, Drew Gilbert, Ryan Clifford, Jeremiah Jackson and Jeremy Rodriguez might each individually carry singular meaning down the road. Collectively, they stand to outdo Bill Haas and Jack Fisher as special draft classes go, and that’s with Fisher having thrown all those innings. They have way more potential than the 22 fellas the Mets selected in October of 1961 did by October of 1961. No offense to the blessed memories of Hobie Landrith and Don Zimmer and everybody else the National League served up on a tarnished platter to the true Baby Mets. NL owners from Los Angeles to Philadelphia weren’t exposing who they were exposing to New York because they thought the Mets could use some promising young players. A few were relatively youthful and a couple crafted representative careers beyond 1962, but the crop didn’t contain much cream, and it’s not like Joan Payson could simply take out her checkbook and make monetary magic.

Steve Cohen can. It doesn’t always conjure a winning record. Witness 2023, when the payroll everybody loves to cite added up to a sub-.500 record by late July and little chance it was going to pay any competitive dividends. Thus, the special draft we just saw. Steve went out and got himself his very own prospect class, the way a few above-it-all baseball owners used to before the amateur draft was instituted in 1965. The idea of the June draft was to level the playing field so the teams with all the money and the scouting and the money and the glamour and the pinstripes and the money couldn’t just go out and sign everybody they wanted. A team like the Mets, who were wallowing in their fourth basement season, could now have a great chance to improve if they selected wisely and nurtured carefully.

Nearly sixty years later, that’s sometimes worked and sometimes hasn’t. What the Mets really needed come 2023 was an advantage over everybody else, which karma kind of owed them after the 1961 expansion draft. Perhaps that was karma spotted sitting at Steve’s table at 21 the other afternoon. I picture him at his booth, separated from the merely wealthy by a velvet rope, the maître d’ bringing him a telephone and Monsieur Cohen directing Billy Eppler, “no, I want TWO top-five prospects from the Astros — tell ’em that’s the penalty for finishing so far ahead of us in ’62…yeah, I call THAT the Cohen Tax!”

No, it probably didn’t happen that way, but it’s hard not to be romantic about baseball.

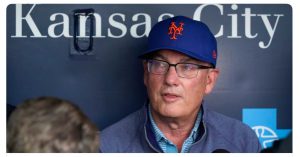

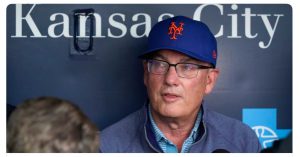

Mets owner Steve Cohen announces he has purchased the municipality of Kansas City, Mo., and plans to use it as a pied-à-terre. In the reality of the moment, the Mets, carefully supplemented for all the years ahead when Max Scherzer and Justin Verlander are putting up their feet while polishing their Hall of Fame induction speeches, are currently stripped down to their shorts. It shouldn’t feel that way, given the several legitimate star types the Mets continue to employ, but in Kansas City Wednesday night, the operative word was yeesh. Seven, eight and nine in the Met batting order were second baseman Jonathan Arauz, center fielder Rafael Ortega and left fielder Danny Mendick. Their presence as one-third of a lineup in a major league game that counted drove me to examine the box score of July 23, 2015, the night of the notorious SOS — Save Our Season — lineup Terry Collins sent out to face Clayton Kershaw. That was the offensive attack that featured John Mayberry (.170/.235/.330) batting cleanup and Eric Campbell (.179/.305/.283) protecting him in the five-hole. The Mets were shut out on three hits, and, with the implicit cry for help having been heeded, the days ahead would bring Michael Conforto, Kelly Johnson, Juan Uribe and, ultimately, Yoenis Cespedes to Flushing. Season saved. Trade deadlines were so much more fun back then.

Thing is, despite immediately thinking of the world’s worst lineup when looking at Arauz, Ortega and Mendick, the lower portion of the Mets’ order eight years ago wasn’t so bad. Lucas Duda batted sixth. Juan Lagares batted seventh. Granted, dreamy Anthony Recker wasn’t exactly scalding the ball in the eighth slot (.130/.266/.241 entering that evening’s action) and the Bartolo Colon who had yet to homer batted ninth. But Colon was diligently working on his power stroke, and as with George Weiss, the long game would prove he knew what he was doing.

Arauz. Ortega. Mendick. Reed Garrett and Phil Bickford jogging in from the bullpen for good measure. These are the Mets — along with the more familiar Kodai Senga (5.2 literally muddy innings), Francisco Lindor (0-for-4 while leaving seven runners on base) and Mark Vientos (failing to score from second on Arauz’s surprise base hit after sliding somewhere behind rather than into home plate) — who lost to the Royals in Kansas City, 4-0. The Royals are essentially this year’s version of the 1962 Houston Colt .45s, until this week barely better than the nearly abandoned Oakland Athletics. The 1962 Mets lost 13 of 16 to the 1962 Colts, plus the one rainout and the one tie. The 2023 Mets have lost two in a row to the 2023 Royals. I’m sure there’s no connection. The 1962 Mets had more players one was likely to have heard of.

Buck Showalter brushes off questions about injuries or other misfortune with, “Nobody feels sorry for us.” I imagine there’s plenty of gleeful hand-rubbing around baseball over the Mets having fallen from the upper echelon of expectations. Steve Cohen signs whoever he wants. Steve Cohen converts whoever he signed who he no longer wants into his own personal supplemental draft. Steve Cohen flies into Kansas City, sits in the dugout between losses to the Royals, reminds reporters that the pre-Arauz/Ortega/Bickford Mets “had shown no consistency” and reiterates that “hope is not a strategy”. His summation of the Mets trade deadline activity didn’t exactly indicate the sentiments of a chastened gazillionaire:

We thought we got a great return for the people that we traded. We weren’t sure that was going to happen. I would’ve kept the players it if turned out it was going to be a mediocre return. It turned out that it’s a moment in time where other clubs are thinking very short-term, and I was thinking more intermediate and long-term. I was able to take advantage of that.

The process was breathtaking. The results are a while from occurring. In the interim, all those other general managers who sent the Mets top prospects believe they strengthened their teams to win the World Series this year. No more than one of them can be right, and it’s quite possible none of them will be. Then the intermediate and long term will kick in and the Mets’ supplemental draft class, along with the regular one from June, will continue to develop, and, unlike these games in Kansas City and the rest of this year, we’ll have something to look forward to.

Advantage Cohen? Money talks, but time has a way of telling.

National League Town has a way of telling the Mets’ trade deadline story, too. Listen in here.

by Jason Fry on 2 August 2023 12:51 am Some days can’t possibly be summed up by one post. So consider this one just the start of a conversation that kicks off tonight but will go on in some form for years.

The Mets traded pretty much everybody. Justin Verlander went back to the Astros, where — as I semi-seriously predicted — he’ll now face off with the Rangers’ Max Scherzer for a division title. Tommy Pham went to the Diamondbacks. Dominic Leone, not even the 20th guy on the roster I thought anyone would want, was shipped off to the Angels.

We all thought the Mets were going to merely tinker with their plan to spend big on free agency in the short term until their farm system was rebuilt. We thought that meant keeping guys on 2024 contracts and supplementing them with more short-term mercenaries. Instead, the Mets decided to use the money already spent on those high-priced free agents to, in effect, buy prospects, accelerating the farm rebuild in ways the draft doesn’t allow.

It’s interesting, bordering on audacious — where most ballclubs (and hell, most people) have trouble accepting the idea of sunk costs and admitting mistakes, Steve Cohen just shrugs. It’s a gambit that may launch a thousand business-of-baseball seminars.

Remember that term: business of baseball. We’ll come back to that in a minute.

What was already an earthquake of a trading deadline came with an additional tremblor courtesy of Scherzer’s account of his conversations with Billy Eppler and Cohen. Scherzer said, essentially, that he was told the Mets now saw 2024 as a retooling year and 2025-26 as their next window of contention, meaning they wouldn’t be shopping for top free agents.

I have no reason to doubt Scherzer, who’s shown himself to be financially and strategically astute and has always struck me as honest, sometimes to a fault. So that leave two possible explanations for the gap between Eppler’s talk about this not being a liquidation and the focus turning to 2025-26.

The first is that Eppler soft-pedaled what 2024 will look like competitively and Scherzer spilled the beans. And hey, that’s possible.

But I think the second explanation is more interesting. I have no inside knowledge whatsoever, but I wouldn’t be shocked if it went something like this: With 2023 a disaster, the Mets decide to go beyond just trading the free agents to be and listen to offers on Scherzer, who no longer looks like much of a reliable commodity anyway. That process crystallizes Cohen’s thinking about what’s happened and the best path forward, and he does what a smart, unsentimental hedge-fund guy does: He concludes the current plan isn’t working, pivots to a new one, and wastes no time seeing it executed, because what’s the point of waiting?

The speed of that takes most everybody by surprise, including Scherzer and a bunch of his soon-to-be ex-teammates and Eppler. This isn’t how baseball franchises are run — though maybe it should be.

(Sticking with the Athletic — if you don’t subscribe, you really should — Will Sammon sees Eppler as the prime architect of all this. He’d know better than me, but I dunno — it feels more like Cohen’s mind at work.)

Whoever’s hand was on the tiller, we wind up back with the business of baseball, and the other part of this conversation.

The new plan strikes me as smart. (Hell, I thought the previous plan was smart — it just didn’t work out.) But that will be cold comfort for the rest of the year, when a bunch of dudes cosplaying as Mets lose a bunch of games, and it will cold comfort next year, when the Mets will likely be a team with a bunch of pieces bolted on and assessed and repositioned and tossed away — a team that we’ll all know is waiting to become something that it isn’t yet.

The business of baseball stuff will be cold comfort on nights like Tuesday, in which someone named Rafael Ortega played for the Mets at 8:10 pm, 40 minutes after I learned Rafael Ortega was Met property. The Mets and Royals, 2015 World Series opponents turned thoroughly irrelevant outfits, played a long game that was alternately torpid and sloppy, with the Mets taking a 6-4 lead in the 10th on a Francisco Alvarez homer, immediately surrendering that lead when closer by default Brooks Raley reported for duty without a decent slider, and then —

— oh God do we have to?

I suppose we do. The Royals loaded the bases and with two out the just-recalled Josh Walker was entrusted with getting the Mets to an 11th inning. Walker somehow took the mound without a pitch com; Alvarez tapped his ear and started to come out to address the lack; Walker went to step off but got his foot stuck in a hole on the mound; and the umpires called a balk that brought in the winning run.

Yes, that’s right: The Mets lost on a walk-off balk. A walk-off balk committed by a pitcher who didn’t throw a single pitch. That really happened — it’s not some LOLMets meme invented by a spiteful person to test the limits of credulity.

It really happened. It was embarrassing and infuriating and amusing in a bleak way and most of all it was deeply stupid.

One day it’s possible that we’ll talk about the 2023 trade deadline and admire how what the Mets did taught a generation of baseball fans the value of not being sentimental. That day may even come pretty soon. But until then, I fear, there will be a lot of days that will be embarrassing and infuriating and deeply stupid.

by Greg Prince on 31 July 2023 12:21 pm Having ten days earlier properly commemorated the 50th anniversary of making Flushing my recurring personal destination, I opened my second half-century of going to Mets games Sunday afternoon by taking a left field Promenade Box eye’s view of The Great Justin Verlander proving effective enough to a) quell the Washington Nationals by a score of 5-2, and b) restore a grain of dignity to the entire New York Mets enterprise after the actions of the night before. The night before, the Mets on the field shambled to an 11-6 loss that would have been embarrassing had this season been capable of any longer generating on-field embarrassment…though it’s not like many will remember the night before for the loss on the field.

Saturday night, the Mets traded The Great Max Scherzer to Texas for, technically, a highly rated prospect, but mostly to put a bizarre relationship behind them. Whether Luisangel Acuña emerges as one of the great time-release trade deadline gets or ultimately has us coupling his name with Dilson Herrera (rather than Luisangel’s older brother), the key to the deal, beyond the involvement of lots of money, was the sense that something was over. What it was I’m not quite sure.

Scher, why not? If the Max Scherzer Appreciation Society had a Metropolitan Area chapter, I wasn’t its president, and I neglected to remit any dues. For a while I felt I felt a tad guilty that I never exactly vibed with Max as a Met. I welcomed his arrival as one would have been silly not to, and I definitely didn’t feel the orange and blue was disgraced by his presence in the colors. This was Max Scherzer, multiple Cy Young winner, world champion, competitor of competitors, and he wanted to be a Met! Or he took the Mets’ owner’s megabucks, but he could have gotten paid handsomely by anybody. Scherzer stood as a validating figure on the eve of the 2021-22 lockout. This is a serious team that attracts serious players with serious money. This could be some kind of era we’re heading into.

It was. It just didn’t last as long as we might have liked. We should probably learn to expect that.

The Scherzer who merits generous dollops of appreciation, no matter how it ended, flickered in and out of sight. Some starts were markedly better than others. Some streams of his consciouness were more agreeable than others. He took care of his minor league teammates when on injury rehab assignments. He hosted impromptu graduate seminars for his fellow starters after he took a dugout seat upon completing his best sets of innings. That was in 2022. As Steve Gelbs noted Saturday night (and I had been thinking in the days before), Scherzer U. seemed to have shut down in 2023. Maybe the old professor didn’t feel he had any lessons to share once his outings stopped earning high grades.

The Scherzer who positioned himself to go unmissed was the one who didn’t come through in the two biggest games he pitched as a Met. That’s a pretty transactional way to process a future Hall of Famer, but Max was here for the bottom line, and so are we sometimes. What bugged me more than his sliders flying over fences versus the Braves and Padres was his insistence, after the latter occasion, that he’d figured out what he’d done wrong and it was gonna be or would have been fine in the next playoff start that never came, as if it were that easy (which it wouldn’t be when 2023, the pitch clock and sweat and rosin came along). A friend of mine remarked Scherzer’s Met stay replicated T#m Gl@v!ne’s. Nah, I replied, retaining my utter disdain for the Manchurian Brave ever donning Met duds — at least Gl@v!ne won a couple of playoff games.

Now and then, Scherzer would conduct his postgame media scrums while wearing his Mets cap, yet as hard as I’d stare into the TV and want to see Max Scherzer, co-ace of the New York Mets, he came across as Pedro Borbon in the aftermath of the Pete Rose-Buddy Harrelson brawl. Borbon was the Reds reliever who got into it with Buzz Capra, and was in such a rage when it was over, that he mindlessly picked up and put on a Mets cap (before realizing his faux pas and taking a bite out of it). Free agency has made player/team identities far more malleable, but some guys can make the hats and the jerseys fit better than other guys. Scherzer always looked like he should be wearing one of those obviously fake uniforms in a commercial whose sponsor hires the player but can’t license his accoutrement. A script “Max” across his chest would have fit Scherzer perfectly.

When Max told reporters, after a refreshingly splendid start Friday night, that the deletion of David Robertson from the Mets’ plans meant he needed to have “a conversation” with those determining the construction of the roster, that should have been a signal that a Lyft had been summoned. During the winter, Kevin Durant nodded upstairs in a similar direction when the Nets rid themselves of mercurial (to put it too kindly) Kyrie Irving. Shorn of Irving and reunited with Spencer Dinwiddie, the Nets were going to be a more pleasant bunch to live and die with, but probably not an immediate title contender. The fan in me thought maybe Durant would internalize the challenge of leading a different, pluckier kind of squad, and…nah, KD wanted to chase another ring ASAP. One of the best players I ever rooted for on a regular basis couldn’t bail fast enough. Now I root for Mikail Bridges and Cam Johnson, the guys the Nets got from Phoenix for Durant. Fandom goes on like that.

If you listen in, you probably won’t hear any mention of the fans. Fandom went on Sunday minus Scherzer, who the Mets were reportedly in the process of trying to move to Arlington anyway before Max cleared his throat, but still with Verlander. Whether Verlander is here by Tuesday at 6 PM is part of the remains-to-be-scenery that serves as backdrop to the trade deadline runup. Four months ago, conventional wisdom wouldn’t have dreamed the Mets and the trade deadline would have anything more to do with one another than the fetching of some bench or bullpen reinforcement for the drive to October. The drive to October now clearly has a U-Haul trailer hitched to the Porsche. A dozen teams will go to the postseason. Maybe Verlander will pitch for one of them. On Sunday, as my LIRR train pulled into Jamaica, a voice called out, “anyone know if Verlander’s been traded yet?” It wasn’t asked with the tone of someone rushing to Flushing to wish Justin a bon voyage.

When I stepped onto Mets Plaza Sunday afternoon, I half-expected to be overcome by the aroma of season tickets burning in the adjacent parking lot. That’s what Giants fans infamously did in the Meadowlands to express their disgust as 1978, the 15th year of continuously lousy football, wound down. In virtual corners of Metsopotamia, we’ve been holding bonfires since April, lighting them on our keyboards rather than with matches. In real life, you’re not going to see people show up at Citi Field on a bright, sunny Sunday to set fire to their season tickets. For one thing, are season tickets even flammable anymore? Wouldn’t you have to set your phone ablaze to register your protest these days? For another, if you’ve trekked to a Mets game, no matter what the Mets didn’t build and how they’re compelled to disassemble it, you’re not there to register a protest. You’re voting in favor of baseball.

It was a beautiful day for a ballgame, all those pesky rain delays from the past week having led to clear skies and cooler temperatures. The Promenade Box location I chose averted the beating sun from the second through the ninth inning. Save for an audible grumble directed at a Daniel Vogelbach groundout, I heard no boos while seated Sunday. When the NOISE METER was activated, I heard nothing neither my friend Mark nor I was saying, but that sort of interruption was held to a blessed minimum. If the crowd GOT LOUD, it was to convey enthusiasm for Francisco Lindor homering and collecting three hits; for Jeff McNeil legging out a triple; for Pete Alonso knocking in two runs; for Omar Narvaez knocking in one; and for Met for the rest of his contractual days or until his conversation with the front office/ownership has its intended effect Justin Verlander.

The prevailing “thrilled to be here even if Max apparently wasn’t” mood enabled us to enable the Mets. If the Mets didn’t make us regret our mood, all the better. I learned twice in 1999, once in September and once in October, that no matter how mad “everybody” is at the Mets — in those cases for having lost in piercing fashion the days and nights before and thereby endangering the thread-hanging season — most everybody who actually attends the game will give the Mets the benefit of the doubt before the game starts. The two episodes I’m thinking of involved the 1999 Braves as opponents. Of course we cheered our heads off for those Mets despite cursing out those same Mets on our way to Shea. If you couldn’t bring yourself to root for those Mets against those Braves, you might as well have burned your tickets.

JV has continued to traverse his comeback from ordinary to extraordinary, definitely tilting in the desired direction Sunday. If five-and-a-third innings of one-run ball versus the one team in the division certifiably worse than yours isn’t a Cooperstown signifier, Verlander did that thing a person loves to see from a starting pitcher. He worked out of trouble in the first (one run) and got stronger as the day went on. The Mets hit Old Friend™ Trevor Williams enough to give Justin breathing room, and when Verlander left the mound in favor of David Peterson, most of us rose to applaud the starter. Maybe it was for the five-and-a-third; maybe it was for the 250th career win that three-and-two-thirds of adequate relief would secure; maybe it really was for a Justin-case fare-thee-well now that we were in an even better mood.

Much as I was excited at the beginning of July when I realized I was going to see the Justin Verlander pitch in person, Mark was similarly delighted when he checked the probables a few days earlier. As we shared in this rare treat of witnessing a 249-game winner striving to reach an even more exalted plane, we got to talking about Great Pitchers We Have Seen and found ourselves not watching Verlander all that closely. Mark and I don’t meander from the action when we go to football games together. Football games demand your attention. Baseball games gently suggest we invoke “ancient names out of thin air,” to use Mark’s phrase. Soon enough, the phones we didn’t burn were out, and we were scrolling the list of the 200+ Win Club.

Mark, whose baseball fandom goes back to the waning days of the Giants calling the Polo Grounds home and the Dodgers hosting visitors at Ebbets Field (even if his grandfather refused to take him to Brooklyn), personally witnessed a lot of the greats and damn goods. Mark saw Warren Spahn pitch for the Mets (before Spahn, like Scherzer, made it known he couldn’t take the losing anymore). Mark is pretty sure he saw Billy Pierce pitch for the White Sox against the Yankees. Luis Tiant? Check. Steve Carlton? Absolutely. Mark wasn’t as certain if he ever saw Juan Marichal, though we both claimed Gaylord Perry. I got my glimpses of Frank Tanana in a Mets uniform. Mark had plenty of looks at Bob Gibson; I hope he ducked. He didn’t see Pedro Martinez, he doesn’t think, but I sure did. Our Seaver sightings culminated in No. 299 at Fenway (me) and No. 300 in the wrong New York stadium (Mark). Neither of us caught Max Scherzer pitching for the Mets, but together we saw him toy with our side as a Nat in 2016.

And so on and so on. There was Justin Verlander doing his thing very well in a Mets uniform, but we didn’t direct the bulk of our concentration toward him, or Peterson, Adam Ottavino and Brooks Raley preserving that thing he did. We went to a game and talked about other games. We talked about the Mets as much in the abstract as we did in concrete terms. As Mark will in lesser Met seasons, he tries to discern that one good push that will somehow inject them into the race. Neither of us really believes it’s a possibility right now, but Mark measured the distance from .500 (five games) and I appraised the overall strength of the current Wild Card contenders (“none of them is that great”) and concluded absolutely nothing that would truly ignite our dormant optimism. But it really was a beautiful day for a ballgame.

On the train ride home, I caught up on Verlander’s desire for a Scherzerian conversation about the club’s trajectory and whether he sees himself as a part of the “repurposing” Billy Eppler has begun talking up after studying hard for the euphemism portion of the SAT. I honestly don’t blame employees for flexing their empowerment muscles, even if there’s a piece of me that wishes everybody first and foremost felt they were a part of our team. It is our team, you know, even if we don’t compose it or own it. We’re the only ones who care about it ’til death do us part. That gets overlooked in the trade deadline conversations. Scherzer and Verlander aren’t going to bring up the fans. Eppler and Cohen aren’t going to bring up the fans. It is left to the fans to bring up the fans, but all the fans want, mostly, is a team whose season will extend deep into October.

That would be swell, but you know what I find myself wanting most? I want an era of Mets baseball. A very good era of Mets baseball. I want to feel as if everything isn’t going to change just because 6 PM Tuesday is fast approaching. I want to get to an offseason and not click refresh incessantly in search of the next multiple Cy Young winner being satisfied enough with an enormous monetary offer to model our clothes for the cameras. I’d like trades that aren’t clever in theory though we’ll have to wait for history’s final verdict, but trades that fill the lone need we have immediately because, except for that one missing piece, we have everything we need in this era. I want to know my team and experience my team and not have to acquaint myself with a wholly new version of my team just when I’ve gotten to know the one I thought was gonna stick around for a while.

Plus they should be very good. It’s obviously not a dealbreaker, but if I’m having a conversation and I’m listing my needs, that would be near the top. But stability — not to be confused with stagnation — would be most ideal. When the Mets were stumbling in June and the manager was making some questionable bullpen decisions, a murmur of FIRE BUCK began to be heard over the noise meters. Such resolution was never a serious possibility in the moment, but man, did I not want to hear it in any case, less out of personal loyalty to or affection for Showalter, but because, geez, haven’t we done this already? Haven’t we cycled through hapless managers and yearned for a steady hand attached to a mind that seemed to know what it was doing more often than not? Didn’t 2022 land us in that place to stay, at least for a few years? Are we really ready, I asked myself, to toss Buck Showalter overboard because it’s been a weird year and a horrid month? And wasn’t Steve Cohen supposed to represent the end of all this?

Maybe 2024, if Buck’s still here and the floundering continues unabated, will indicate the hair-trigger types had the right instinct, so why did we wait? Or maybe 2024 will shake out the insipidness that has enveloped Mets baseball in 2023 and we’ll have returned to the right track, led by Lindor who’s gonna be here for years, and Nimmo who’s gonna be here for years, and McNeil who’s gonna be here for some years, and Alonso, unless he has a conversation with somebody in which he shares his long-term doubts and free agency desires. Sometimes Lindor overswings or Nimmo slumps and I calculate how much of their probably immovable contracts (though never say never with Uncle Steve) are left, but generally, it’s nice to know some guys aren’t going anywhere. We finally got a beautiful team to cheer toward a World Series in 2015, and the gutsy 2016 bunch who strove to a Wild Card was already tangibly different. I reveled in the hot finish to 2019, thinking we were young and set for years to come, and the years came, and much of the core of that team was steadily peeled away

The Fab Five, before they broke up. The 2022 Mets of exactly one year ago were the team I was prepared to grow a little older with. I’ve aged plenty watching the 2023 Mets, but I recognize them less and less. As the Max Clock ticked, I thought not only of those dugout seminars that were no longer in session, but of a clubhouse picture that circulated after the Mets clinched their playoff spot in Milwaukee. The starting rotation of Scherzer, deGrom, Carrasco, Bassitt and Walker came together and posed as one. It could have been the Beatles on the roof of Apple Corps, never again to publicly get back to where they once belonged.

If Scherzer had to go, he had to go. If Verlander has to go, he has to go. As I’ve entered my second half-century of game-going, it’s apparent I’m not going anywhere besides 41 Seaver Way. More than ever, I appreciate the company of those friends and those Mets who also wish to stick around for a while.

by Jason Fry on 30 July 2023 12:01 am So now we know how Max Scherzer‘s conversation with the brass went — it turned out to be an exit interview, as Scherzer is on his way to the Rangers (along with $35.5 million through next year) in return for Luisangel Acuna, whom you probably didn’t know is the younger brother of Ronald Acuna Jr. For those keeping score over more than a generation (and if so, applause), the Acunas’ father was a Met minor leaguer in the early aughts. Here’s hoping — for all sorts of reasons — that Luisangel proves a valuable major leaguer; if not, rest assured Greg and I will be ready with sneaky references to Mike Maddux and Pedro A. Martinez for a decade or more.

If I’m feeling paleolithic, the monetary aspects of the Scherzer trade feels at least mildly absurd: $35.5 million is a lot to pay for a prospect, even a good one. But in all walks of life it’s good to resist being paleolithic. Scherzer gave the Mets 90% of a superb initial season, a disappointing finale to that first go-round, and then followed that with an iffy, worrisome sophomore effort. He wasn’t going to get any younger (none of us will), and there was no guarantee that 2023’s issues were going to be behind him. So the Mets sent Scherzer to a contender, added a bonafide prospect in return, and will retool their starting rotation without him.

Without Scherzer and now, it seems pretty clear, without a bunch of other dudes: Seeing what happened to David Robertson and Scherzer once tarp hit field, Tommy Pham, Mark Canha and Omar Narvaez have got to be wondering if the next rain delay will mean their departure. And how funny would it be if the Mets trade Justin Verlander back to the Astros, pitting their two 2023-on-paper aces against each other for an AL division crown?

Stepping back further, though, I keep resisting the impulse to be appalled by the amount of money being thrown around. It’s Steve Cohen’s money, not mine or yours or a kitty that otherwise would go to feeding orphans or building schools, and I keep coming back to the thought that the Mets’ 2023 plan seemed sound: pay a short-term premium for top-shelf starters, try and charge through the window of contention that spending pried open, and then turn to a hopefully restocked farm system.

It didn’t work out — and because it didn’t, the 2023 Mets will be trotted out as a cautionary tale for decades — but so what? Does the plan having failed necessitate some sort of hairshirt nonsense where the Mets pare back spending and take a couple of years to be morose about it? Cohen has enough money to try a modified version of the same plan, only with a younger starter in Scherzer’s place, and maybe one in Verlander’s slot as well, and if you’re thinking about Shohei Ohtani, well, so is everyone else. (I don’t think Ohtani would come here, but hey, half a billion dollars is an excellent way to change someone’s mind.)

I also keep thinking that the outcome of seasons can be plotted on a bell curve. (I should have dressed this up with a fancy graphic, but hey, 2023.) A season in which everything goes right — rookies blossom, veterans find fountains of youth, bounces go your way — goes on the right-hand side on the curve, down below that mountaintop of middle. Think 1969 or 1986 — and hey, 1999 and 2015 and 2022 are over there on the descending right as well. But there are other seasons, ones in which prospects turn into suspects and veterans get old and bounces work out for the other guys. Those go on the left side of the curve — and 2023 may as well be Exhibit A.

Here’s the thing, though: There are no half bell curves. To have a chance at landing on that magical right-side tail, you have to accept that you might wind up on the dismal lefthand side instead.

There’s 1969 … and there’s 1992,

There’s 1986 … and there’s 2004.

There’s 2022 … and there’s 2023.

That’s the way it goes — and frankly, that’s the way we should all want it to go. We just have to grit our teeth when we realize a given year is destined for that lefthand side, and wait with as much patience as we can muster for fate to flip our position.

* * *

Oh yeah, the game: Your chronicler was out to dinner with his in-laws and it was 7-1 Nats when he reported for duty, meaning he missed Carlos Carrasco reducing his trade value essentially to zero by getting strafed (with some oh-so-2023 defense not helping) and a whole lot of unpleasantness. I also missed newest Met Reed Garrett, but here’s betting there are some more debuts ahead.

I did see Francisco Alvarez connect for his 20th homer — now there’s something that’s gone right — and Mark Vientos follow Alvarez’s blast with one of its own, which isn’t bad for a kid who’s been buried on the bench. Poor Brett Baty even doubled, a welcome tonic given that Baty looks both frustrated and like he’s running out of gas.

Does any of it matter? Not particularly — but then nothing else the Mets do on the field will much matter until next April. That’s when we’ll get a chance to assess whatever the new plan is, and to wonder where the new season will land on the bell curve.

by Jason Fry on 28 July 2023 11:58 pm It’s not quite Max Flack and Cliff Heathcote switching teams between games of a doubleheader, but spare a moment of consideration for David Robertson, who was a Met when it started raining and a Marlin when it stopped.

That’s a strange one.

A strange one, but probably not the only oddity heading our way: There was a palpable hum around the Mets as they squared off against the Nationals Friday night at Citi Field, with any player so much as going down the dugout tunnel drawing a curious look. Has Tommy Pham been traded to … oh wait, he just went to the can. Carry on!

At least the Mets played like they were more or less unruffled. OK, maybe an emphasis on the “less,” as Max Scherzer said he needs to have a conversation with ownership about the team’s direction and his future — a reminder, as if you needed one, that $43 million employees are not like most employees. Scherzer will get a friendlier hearing if he keeps pitching the way he did Friday: He was nicked for a homer when he tired in his final inning of work but otherwise superb, with his oft-disobedient slider mostly sliding as directed.

On the other side of the ball, Pete Alonso certainly looks to have shaken off his summer doldrums, connecting for a majestic three-run shot off MacKenzie Gore in the fifth that might have saved the Marlins some money had Robertson waited a night and hopped aboard, then following that with a merely impressive two-run homer to seal the game in his next AB.

With Robertson gone, the Mets are on to Plan C as far as closers are concerned; by Tuesday new possibilities may have unfolded as far as outfielders, middle relievers, starting pitchers and backup catchers are concerned. (Robertson’s replacement is someone named Reed Garrett, whom I confess never having heard of, though rest assured I’ve already secured a card of him for The Holy Books.) Where this will leave the team is of course unknowable; my own quiet hope is that having seen the white flag waved we’ll all be able to let go of this sour, dissatisfying season and simply enjoy the games for themselves. Y’know the drill: One day at a time and the good Lord willing it’ll work out.

Speaking of transitions, we’re on our way to Maine with a weekend pit stop at my in-laws in Connecticut, which meant the game unfolded on the radio via the MLB app. Which, to be clear, is fine: Howie Rose and Keith Raad are good company, though we rolled our eyes at Howie’s extended product placement for some kind of chicken wrap and were mystified at what Keith could have gotten up to in a Nathan’s that couldn’t be shared on radio.

No, the problem is that MLB has pretty much two ads that it runs every half-inning. First you get Spectrum One, advertised via an actually not bad rap, though Emily insists I’m wrong that its lyrics mention “ass down low speeds,” about which I’ll have no comment because I know what I heard. Next you get a radio couple subjecting listeners to an unfunny “you talk in your sleep” bit involving an HGTV lottery and meeting someone named David Bromstad. I have no idea who David Bromstad is but I’m pretty sure if I met him I would punch him in the nose, because I have to hear his name 16 or 17 times if I listen to a ballgame.

There’s a long list of things I think MLB could do better at, and I know most of those things aren’t going to change and are simply the way the world now works. But surely they could sell ads to more outlets than I can count on one hand? Failing that, perhaps they could pay for the straitjacket in which I’ll spend the rest of my days, ass down, moving at low speeds and waiting for David Bromstad to tell me I’ve won whatever the fuck his lottery is.

by Greg Prince on 28 July 2023 11:23 am So much for well-intentioned inertia. The fourth-place Mets aren’t content to do nothing. Fourth-place they appear resigned to, but they’ll be damned if they don’t keep busy while maintaining it. David Robertson was not looking to be moved, yet moved he’s been, to his seventh major league team, traded late Thursday night to the Miami Marlins as the raindrops on the Mets’ 2-1 win over the fifth-place Nationals were still drying. The Marlins, in the absolute thick of a full-season playoff race for the first time since Miguel Cabrera was a rookie, are buyers. The Mets, a little too far outside the Wild Card action to be termed looking in, are sellers. When the Mets opened their high-expectation season at Miami on March 30, I’m sure we all saw this scenario unfolding four months hence.

Robertson, brought in as setup man to Edwin Diaz, then promoted to closer when Diaz’s right patellar tendon had other ideas, was a) mostly successful in his unexpected assignment and b) pitching under an expiring contract. Those two factors will make a non-contender shop a fella who can save games. The Mets went to market.

They brought back two kids, an 18-year-old infielder named Marco Vargas and a 19-year-old catcher named Ronald Hernandez. They’ve never heard of you, either. The ideal scenario is sometime in the mid-to-late 2020s, when David Robertson is an answer you’re kicking yourself for not filling in on that morning’s Immaculate Grid, we will be benefiting in some way from having grabbed such talented youth at the deadline that season when things weren’t going according to plan, but they sure worked out down the line, huh?

Maybe that happens. Who I am to tell a couple of teenagers their dreams won’t come true? Who am I to tell myself that our dreams won’t intersect with those of a pair of prospects? For now, Vargas and Hernandez are people the more ambitious among us will pretend to know something concrete about before they show up on the next MLB Pipeline list.

The reactions in the Met clubhouse provided a few insights into how business is business. You had the determinedly upbeat veterans, Francisco Lindor and Pete Alonso, insisting the Mets’ chances weren’t wholly snuffed as they searched for the right words to show their esteem for Robertson. Lindor called him a great father. Alonso, perhaps indicating that the hitters and the relievers don’t hang out that much, talked about how “decorated” David is in this game. Mark Canha — whose bases-loaded eighth-inning sac fly that followed a sudden 97-minute rain delay delivered the now-forgotten winning run — and Brandon Nimmo emitted the vibes of weary pros who’d attended this rodeo in too many previous lost campaigns. Canha didn’t bother with too many brave words about how it was still possible for the Mets to make a run. Several days remain until the trade deadline. The next run Canha makes may be to catch a flight wherever he is sent.

Kodai Senga, whose six innings of one-run ball typified the effectiveness he’s given the Mets most starts since the middle of June, seemed a little baffled by the late-July rituals unfolding around him. This doesn’t happen much in Japan, he said through interpreter Hiro Fujiwara, adding, in so many words, the most honest thing any ballplayer on a non-contending team may have ever said: this doesn’t really affect me. Kodai explained he meant he still has to prepare for games, and David’s a great guy, but the season goes on.

That it does. For four months, it was essential to have David Robertson rested and ready for just the right moment, whichever inning it arose, usually the ninth. Save situations are what New York Savings and Loan checks were to Leonardo DiCaprio as kiter extraordinaire Frank Abagnale in Catch Me If You Can. As he told the high-end call girl played by Jennifer Garner, the one who only accepted cash, they’re like gold. Robertson was able to cash most of the save situations he laid his hands on, 14 of 17, no questions asked. God help Buck Showalter if he used somebody else and the decision proved counterfeit. Why didn’t you use Robertson? Now Buck will use Adam Ottavino, or Brooks Raley (as he did to raised pre-trade announcement eyebrows Thursday night), or Drew Smith, or whoever emerges as Diaz’s placeholder. In 2018, the going-nowhere Mets traded decorated longtime closer Jeurys Familia to playoff-bound Oakland. Familia was leading the Mets in saves. Their season went on with somebody else closing games. When the season ended, Familia was still the club leader in saves. In seasons when you’re ready to ship your usually reliable closer elsewhere, it likely means you’re not winning enough games to take saves seriously.

There’s a trumpet player who’s a fixture on Mets Plaza before and after every home game. He plays for tips and elicits them by performing the crowd’s presumed favorites: “Take Me Out To The Ball Game”; “Lazy Mary”; “Meet The Mets”. The last game I went to, last week, I noticed he started his postgame set with “Narco,” still the song we think of when we think of protecting ninth-inning leads. David Robertson’s entrance music was “Sweet Home Alabama”. I guess the Mets Plaza trumpeter didn’t make it one of his standards. Good call on his part.

by Greg Prince on 27 July 2023 11:42 am In one of the climactic scenes of the first season of Mad Men, ad agency head Bert Cooper instructed impatient Pete Campbell, by way of exonerating a man originally named Dick Whitman for shadily assuming the identity of the late Don Draper, “The Japanese have a saying: A man is whatever room he is in, and right now, Donald Draper is in this room.” I woke up the morning after Wednesday night’s Mets 3-1 winnable yet ultimately elusive loss to the Yankees drawn to this insight because after playing 101 games, I couldn’t tell you who the 2023 Mets are, nor could I tell you I have any swell ideas to make them better.

They no longer bear any collective resemblance to the team that won 101 games in 2022, even if individually many of the players from then are the players from now. In hindsight, it was a mistake to put much stock in recent past performance, to rhetorically ask, “what’s wrong with these Mets, they won 101 games last year?” because that was last year, and last year left the room last year. Some years more or less pick up where the years that preceded them left off. This year made a mysterious clean break with last year.

The room the Mets are in currently defies easy identification. They are not a powerhouse. They are not a contender. They are not completely out of it. They’re not good. They’re not so bad that they can be completely written off for this year or, given who’s on the team, next year (instantly putting aside some of what I just concluded about one year having a limited relationship to the next). With the trade deadline fast approaching, they do not profile as a buyer. They may not be a seller in that they don’t have that much to sell that anybody is going to go out of their way to buy from them without square pegs, round holes and dollar signs being carefully applied to any transaction of substance. I’m not sure what the purpose of selling would be beyond a vague sense that something is getting done amid a season when something happens every day yet little changes and nothing improves.

Is somebody soaking up playing time and blocking somebody who deserves reps? That’s one of those situations a fan whose team’s immediate aspirations aren’t serious sees as trade deadline catnip. Move Asdrubal Cabrera, get Jeff McNeil in there every day, that sort of thing. Maybe one fewer veteran outfielder clears space for Ronny Mauricio, and I wouldn’t begrudge either Mauricio — who’s still figuring out his potential position — or us from a glimpse or two of what Ronny might do. Finding a taker for Tommy Pham or Mark Canha would accomplish a vacancy, though you never know with this organization if that would mean Mauricio gets a crack at filling it or it just results in more time for DJ Stewart. It’s quite possible you’re quite happy with Stewart or Pham or Canha as human beings representing your team several at-bats per game. You’re entitled.

Do we merely seek catharsis? I’m not putting down catharsis. Catharsis literally feels good. The best part of the cruddy 2003 season, after Jose Reyes was called up, was the dismissal in the weeks that followed of Roberto Alomar, Jeromy Burnitz, Armando Benitez, Graeme Lloyd and Rey Sanchez, each sent away by Jim Duquette, whose elevation to general manager occurred once the Mets got rid of Steve Phillips, whose offing also felt like a cause to light a postcoital cigarette (as I’ve seen done in movies). Sometimes your team is just so bad and you so don’t want to look at those characters anymore that you’ll take action that jettisons a batch of them as a spiritual victory. None among the players who returned in trades in the summer of 2003 directly swung Met fortunes upward — even Duquette didn’t last beyond 2004 — but it literally felt good.

Yet 2023 isn’t 2003. Nor is it 2017, a less toxic but no more competitive setting. At and around the deadline six years ago, the Mets sought and secured takers for Lucas Duda, Addison Reed, Jay Bruce, Neil Walker and Curtis Granderson. The season didn’t get tangibly better or worse. Youth had been served, which generally appeals to our future-leaning instincts. The housecleaning seemed necessary in the will ya look at the dust on everything? sense rather than as an echo of 2003’s geez, it stinks in here, grab the Lysol! Bringing out the vacuum doesn’t always mean everybody you’re trying to remove from the premises sucks. And vacuuming sometimes only accomplishes so much. Drew Smith was the only young player who arrived in those 2017 exchanges to establish roots in Flushing, though promising kids Amed Rosario (now a veteran who gets traded at deadlines) and Dom Smith were called up. Brandon Nimmo received more playing time as that August progressed, and Nimmo’s still here, too. Mostly, the season wound to an end, and the next season came. New problems arose. At least they weren’t the same old problems.

This team, no matter our roughly every-other-night gripes, isn’t The Worst (a distinction one didn’t think would need to be delineated this year), and its components, for the most part, aren’t people a fan can’t stand to look at one day longer. If you can stomach these guys, however flawed they’ve proven themselves as a unit, maybe you do them a favor regardless and find them a good home with a team that already knows it’s a contender. But then you read an ideal chip like David Robertson tell Newsday, nah, no thanks, I like it here. Robertson’s one of those steady veterans who’s moved plenty in his career. He signed with the Mets. He probably thought he’d signed with the playoff-bound Mets, but Mets is good enough for him for now. Barring a Zack Wheeler-type return from the Carlos Beltran expiring contract auction of 2011, do we really need to shop around a professional who’s fine where he is? Sixty-one games remain. Some will need to be saved in the ninth inning. Somebody else could try and probably succeed, sure, but I, too, am mostly fine with David Robertson and his colleagues where they are for two more months.

I’ve been a fan for 55 seasons. I can withstand two months of well-intentioned inertia.

Theoretically, you shed salary by trading veterans with big contracts, but under Steve Cohen, what does that even mean? Nobody’s taking millions and millions off Cohen’s hands, and, though I would never discount millions and millions (I’m never gonna see millions and millions, either), that doesn’t seem like a motivating factor on Seaver Way. Didn’t the Mets eat Eduardo Escobar’s salary? Didn’t they eat Chris Flexen’s salary just for the pleasure of paying Trevor Gott? The owner was once quoted, within the context of a real estate deal in which somebody offered him a million dollars to disengage from negotiations, “What am I going to do with a million dollars?” Uptown problems, as Brad Pitt as Billy Beane said in Moneyball.

So, no, I don’t believe somebody’s going to engineer a Max Scherzer trade nor a Justin Verlander trade, nor, probably, should the Mets be seeking such resolution. I mean, yeah, listen to everything and everybody, but have you seen the Mets’ pitching depth? Neither have I.

With the approximately two months remaining to this season, is there anything the Mets can do, as a very savvy buyer, to catapult themselves from fringe of the periphery of the multiberth playoff jumble to an outside shot at competing for the six seed, a goal which is not mathematically unattainable and is anecdotally enticing? The individuals from 2022, and a few who were added in advance of 2023, still appear capable of that one sustained drive that might push a ballclub 7½ games out to maybe 4½ games out with a splendid week or two, and if you’re that close, who’s to say you can’t get closer? Of course we’ve been saying something like this across the approximately four months the Mets have been playing, usually on the nights they’re not stagnating. Then stagnation kicks in again. If it were that easy, the Mets would be something more than 5-8 since their mirage of a six-game winning streak in early July.

Still, Pete Alonso, whose bat looks alive, will almost certainly be here in 2024. Jeff McNeil, who made three nice catches at a position that isn’t really his, is signed for a while. Brandon Nimmo is signed for much longer. Francisco Lindor is signed forever. Hopefully Starling Marte, also under contract for a little longer, finds relief from his migraines (those things are no joke). Francisco Alvarez and Brett Baty are being given every opportunity to speak for themselves. As much as 80% of the rotation doesn’t give me pause in a good week. Even if coming out of 2022 guaranteed nothing about 2023, I really don’t think we’re groping for scraps of hope like we might have been coming out of a 2003 or 2017 any number of years. And if we’re not satisfied come the end of the regular season, we’ve got an entire offseason to disassemble what isn’t in bolted in place and start semi-fresh.

With 61 games left, there are 549 innings of Mets baseball to be played. Maybe a few less if it rains too much, maybe a few more if there are ties after nine. I’m not expecting miracles. I’m not thrilled with what the first 101 games have yielded, but some years I root for the playoff-bound Mets, and some years, even if it’s not really good enough for me, I just root for the Mets.

At National League Town this week, the subject of Five-Tool Fandom occupies our minds.

by Jason Fry on 25 July 2023 11:52 pm What are the stakes in a Subway Series where both sets of partisans would just as soon not?

The Mets and Yankees have not too dissimilar records (the Mets are bad in a meh way, the Yankees are just meh), are both mired near the bottom of their divisions, and have both stumbled through the summer with their fans shaking their heads and muttering that everything about them is just … off. Injuries, bad luck, bad decisions, bad vibes … like I said, just off.

If you’re me, you show up for the game with a sense of duty … and then find that a game with no stakes can be kind of refreshing.

I was watching with my mom in her new tower lair overlooking Brooklyn Heights and New York Harbor, which has the added attraction of giving you plenty to look at if the baseball becomes too painful and you need to avert your eyes. Which, for once, didn’t happen — the Mets weren’t exactly flawless, but they looked a lot more like the on-paper version of the 2023 Mets than the shabby, smudgy copy of a copy of a copy of a copy we’ve been stuck with. Justin Verlander was a reasonable facsimile of his former All-Star self, Jeff McNeil and Pete Alonso and Daniel Vogelbach all had non-miserable nights in mostly miserable seasons, and we even got an unlikely hero or two. (If you saw Dominic Leone as the solution to the problem he was handed, well, I’ll have what you’re having.)

Meanwhile, the Yankees looked borderline hopeless, with all three outfielders playing as if mildly concussed, wearing cement shoes or both — I was honestly a little worried that former Met Billy McKinney was going to hurt himself or a teammate stumbling around out there. There were a lot of no-name bats, some bad relief … in short, the Yankees looked a lot like that other New York team nobody in the city wants to talk about.

Speaking of things nobody wants to talk about, my mom and I had a moment of shared inattention and so wound up watching the TBS telecast — we were startled late in the proceedings when the TBS crew showed the occupied SNY booth, but stayed where we were broadcast-wise because hey, everybody knows you don’t fuck with a winning streak. Honestly, TBS wasn’t a terrible accidental Plan B: There was a lot of gee, the Mets have been inexplicably bad, but that’s been true in these humble precincts too. On the other hand there was also a lot of trade talk, which I’m already heartily sick of. I guess that counts as another silver lining: For most of the night I was thinking about how it would be nice to beat the Yankees, instead of wondering which mildly useful Mets will get helicoptered off the embassy roof before next Tuesday.

There will be time enough for that, but one more night of simpler fare sounds maybe sort of not so bad right now. Hey, it would be nice to beat the Yankees. It worked out for one night; let’s give it another go, fellas.

by Jason Fry on 24 July 2023 3:53 pm The Earth keeps going around the sun; the Mets keep going in circles.

On Sunday night they dropped the rubber game of their series with the Red Sox in numbingly familiar fashion: no hitting, bad pitching, bad defense. To which we might add that they looked torpid and useless, trudging around morosely while being dismantled by Boston relievers no one had ever heard of. (OK, I’d heard of Joely Rodriguez. That didn’t make it better.)

If this is the setup for a wild-card run, well, it’s sure one hell of an okie-doke.

Another week of playing like … well, like the 2023 Mets ought to bring a merciful end to delusions about contention, formally shifting the conversation to what the Mets might be able to obtain as sellers. Which is … what, exactly?

Sure, someone will probably help themselves to David Robertson, and a veteran reliever such as Adam Ottavino or Brooks Raley would likely find a market. But beyond that, who wants what we’d be selling?

Who’s paying some pro-rated chunk of $43 million to watch Max Scherzer gamely explain yet again that he’s working hard on not being bad, or to see if Justin Verlander can consistently be more than a No. 4 starter? Who’s going to think they’d get a Carlos Carrasco different than the guy who was strafed at Fenway while the ESPN crew embarrassed themselves asking Rafael Devers moronic questions about ice cream? Who’s going to pay for Tommy Pham and his obviously still not healed groin? Is someone going to see Mark Canha and his middling production as a difference maker? Starling Marte can’t even endure bright light right now, to say nothing of big-league pitching.

Not even full Blow It Up mode is likely to work: What would you get for Pete Alonso given that he’s been an offensive nonentity for a month?

Rather than speculate about the depressing returns for these various old, hurt or underwhelming commodities, I’d like the Mets to consider another tack: trade me.

Think about it: Wouldn’t it be wonderful to wake up as a fan of the Orioles or the Reds, dreaming of the postseason, marveling at your new surroundings and thinking about how you might be able to help your new club?

I don’t want to read about Double-A lottery tickets who might prove valuable if they improve their mechanics or strike-zone judgment (spoiler: they won’t). I want a reason to care about baseball and a goal that isn’t awaiting me in some other season.

Hey Steve: Trade me!

by Greg Prince on 23 July 2023 11:30 am These first-place New York Mets keep building on what they’ve accomplished. They’ve been doing it from Day One of this season. They’re still doing it. They have to keep doing it, not only because the second-place Atlanta Braves, currently three games behind us, are as formidable an opponent as the 1984 Cubs or 2022 Yankees, but because there’s little chance somebody will stand before a throng of Mets fans 38 years from now and wax rhapsodically about the 2022 Mets who showed what a group of talented athletes — some if not all young, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed — they were unless there’s a payoff in October.

—from Faith and Fear in Flushing’s report on the 98th game of the 2022 New York Mets season

The Mets won their rain-interrupted Friday game on Saturday afternoon before losing their meteorologically copasetic Saturday night game, which was originally scheduled for Saturday afternoon, except it had to be pushed back in deference to completing the suspended Friday contest that would have been a washout under previous rules because it hadn’t gone at least four-and-a-half innings with the home team ahead, or five innings either way, thus Fenway Park wound up hosting a Saturday day-night doubleheader between the Mets and the Red Sox that wasn’t really a day-night doubleheader, except two different games were contested and resolved, one in the day and one in the night, and they were split.

Got that?

Through 98 games of the 2022 season, the Mets carried a record of 61-37. Through 98 games of the 2023 season, the Mets carry a record of 46-52. That’s 15 games worse. The only other time the Mets were as many as 15 games worse through 98 games versus the year before was the not so sainted year of 1993: 33-65, down from 48-50 in 1992, a season never to be confused with 2022, which, for all the carping it eventually inspired en route to a frustrating second-place finish and premature playoff exit, included 101 wins, a total we are 10 Met losses from guaranteeing we won’t see in 2023.

Got that?

Despite the Saturday night loss at Fenway, the Mets came away with the evening’s most shareable highlight when, in the fourth inning, Francisco Lindor singled, Pete Alonso doubled, and Jeff McNeil delivered everybody’s favorite kind of clip, the Little League Home Run. Technically, McNeil singled and took second on the futile throw home that didn’t nail Alonso. Alertly, Red Sox catcher Jorge Alfaro threw to second to try to get McNeil taking that extra base. Well, not so much to second, and not really toward second. That sucker sailed like it had eyes on the America’s Cup. Off to deepest center field it bounced, and around the bases our Squirrel flew. WHEEEE!!!! FOUR BASES!!!! Three runs, too, for a regrettably short-lived 3-2 Mets lead. Yet the real excitement came in realizing what we had just seen before seeing Jeff cross the plate. Lindor, Alonso and McNeil had all gotten hits in the same inning. When, I wondered, had that last happened? I had to look it up. This was Game 98 of 2023. It had last happened in Game 87 of 2023, July 6 at Arizona. Far more telling was learning the game of July 6 — 16 days before the second-ish game of July 22 — didn’t just contain the previous inning in which arguably the three mainstays of the Met lineup had gotten hits in the same inning; July 6 had been the last time Lindor, Alonso and McNeil had all gotten hits in the same game.

You get that, and you get a sense of why the New York Mets of 2023 are not just worse, but historically worse than the New York Mets of 2022.

That and Max Scherzer giving up four home runs and it not seeming all that surprising. A person didn’t have to look up the last time Max did that. It’s ingrained in the Mets fan memory that it came in the first game of the 2022 National League Wild Card Series, a round the Mets wouldn’t have been playing in had the Mets won 102 games, which, in retrospect, feels like a greedy ask, considering the Mets will likely fall dozens of bricks shy of their 2022 load of 101 in 2023, though, at the time, just beat the Braves once on that final weekend and you’re not playing the Padres, and no matter what happens in the playoffs, we’ve at least got a divisional flag for our collection. Except Scherzer (like deGrom and Bassitt and the offense) weren’t up to the task, and so try again to beam with pride that the Mets got anything at all for their 101 wins a season ago.

Anyway, Max gave up four home runs at Fenway, and the bullpen as a whole wasn’t as effective in keeping the game close on Saturday night as it had been in protecting Friday’s rainy lead on Saturday afternoon, which turned out to be a shame, considering the Mets roared back from a great distance in the ninth inning on Saturday night, cutting Boston’s sure-thing lead from 8-3 to a throat-clearing, collar-tugging, Dunkin’-spilling 8-6, and had the tying run at the plate with two out. The batter representing said run was Daniel Vogelbach, who had homered before Friday night became Saturday afternoon, providing the margin of 5-4 victory, and a similar swing might have catapulted either the Mets or Vogelbach’s trade value who knows where? Maybe as high as when the 2022 Mets traded for him? Except Vogelbach popped out, and the not-quite-doubleheader fell short of a sweep, and the Mets have to sweep most every game they play if we wish to kid ourselves a little that they’re playing for stakes beyond the mundane…though the mundane has its moments. By that, I mean DJ Stewart laid down a beauty of a drag bunt for a single in the top of the ninth on Saturday afternoon. It didn’t lead anywhere in terms of insurance runs, and it didn’t go viral like McNeil’s Little League Home Run, but it surprised the defense; it moved Mark Canha up to second; it put Stewart on first; it was Fenway Park in daylight; and it wasn’t raining. Sometimes you watch baseball to see things like that and hope for the best.

Sometimes you get what you get. This year, we’re getting the 2023 Mets.

|

|