The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 21 July 2023 1:26 pm Last week, Major League Baseball released its schedule for next year and I shrugged. It was the epitome of too soon. But last year, when this year’s came out, I figuratively unfolded it and zeroed in on one particular box in quest of pertinent information:

Would the Mets be home on July 11, 2023?

They would not. Nobody would be, except for the American League All-Stars playing the National League All-Stars in Seattle, both squads in uniforms best described as unfortunate and worse (with worse topping unfortunate, 3-2). The Mets wouldn’t be home again in July of 2023 until after the break, contesting a weekend series with the Dodgers. No, that’s no good. The Dodgers are too much of a draw and the weekend wasn’t what I was looking for. Next in, the White Sox. Maybe. A lower-profile visitor suited me, even if they were interlopers enabled by interleague inanity. I just can’t accept that we play every AL team every year. I should probably get over that some, because it’s not going away. Fine, the White Sox. The White Sox would do fine. Especially on Thursday afternoon, July 20, 2023.

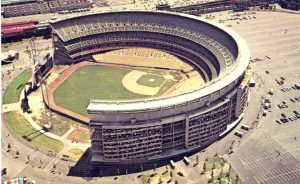

Bingo. That was it. That was going to be my 50th Anniversary Game.

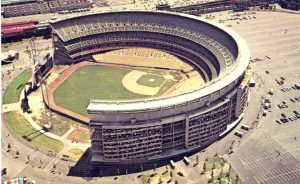

As some of you may have read in this space, I just passed the 50th anniversary of my first game at Shea Stadium, a milestone event in the life of a ten-year-old fan. I knew it was a milestone on July 11, 1973. I knew it would be a milestone before July 11, 1973. All I needed was the date in advance to mark it down as the start of something I’d continue to do for as long as it was possible. My first Mets game. Having been taken with the Mets on TV and in the newspapers in 1969, I waited long enough for it to happen. Needing to be taken to the Mets, I had to wait. Nobody was volunteering to take me in 1970 or 1971, and in 1972, when it was supposed to happen for the first time, I caught an overblown cold that kept me at home.

When I was signed up for day camp in the succeeding summer and saw the list of activities, my eye was drawn to July 11, Mets vs. Astros at Shea Stadium. It was finally going to happen. And, as detailed in this remarkably well-preserved report, it had happened. I had gone to a Mets game.

I’ve been to quite a few since. I made it to 402 regular-season home games at Shea Stadium and, through the first day of July of this year, 305 regular-season home games at Citi Field, adding up to 707 and counting. There’ve been postseason games and exhibition games and games on the road, too, and they’re all filed and accounted for, but 402 and 305+ were my primary numbers entering Thursday. My tentative plan, assuming the owner of the New York Mets doesn’t decide to implode the current Wilpon-conceived facility and create a vastly superior CohenDome in its stead ASAP, is to live long enough and go regularly enough to match my Shea Stadium total of 402 at Citi Field, then seriously consider leaving it a tie for all eternity. But that somewhat morbid calculation is for another day. Yesterday, Thursday 7/20/2023, was for the numbers that started it all: 7/11/1973. My 708th Mets home game, which had no particular magic to it numerically. My 50th Anniversary Game, the concept of which had captivated my imagination for nearly a year.

Mets vs. White Sox at Citi Field. How could I resist?

I hadn’t said any of this out loud to anybody, because when you live so much in your head, you tend to think the things you think about need an Alan Suriel or Hiro Fujiwara to interpret them. The night before the day game, my wife happened to ask me, “When’s your next game?”

“Maybe tomorrow,” I said. “It would be my anniversary game: 50 years since my first game, more or less.”

“Your anniversary game!” she cooed. Stephanie thought it was adorable and appropriate, more evidence I married the right woman.

I checked StubHub for a cheap ticket. I wanted a cheap ticket, and not just for budgetary reasons. I wanted to sit in Promenade. It would be self-flattering to invoke Bill Veeck here…

I have discovered in 20 years of moving around a ballpark, that the knowledge of the game is usually in inverse proportion to the price of the seats.

…but mostly the baseball experience tends to feel more authentic to me upstairs. There are real fans and knowledgeable fans everywhere in a ballpark, but Promenade says, at least to me, I simply wanna be here for baseball. Plus I’d be going alone, given that I was the only person I knew who would totally get what I would be seeking in this outing. Promenade is the official level of loners in a mood. That was gonna be me.

Not a bad mood, by any means. To the contrary. I found my cheap ticket, Row 8 of Section 518, and I had myself as company, I made a turkey and mozzarella sandwich and I was off to the LIRR. I looked up and down the platform at others in orange and blue clearly headed for changes at Jamaica and Woodside like I was. We were tacit co-conspirators in the late morning in the middle of the week. We were all going to the Mets game. We were all getting away with something. I ate my sandwich on the train. My mood was great.

Off the steps from the 7 usually recalibrates my mood because I’m thinking about lines and security and the sense that we’re all suspect at Citi Field, no matter what price our ticket, but I pre-empted all that when I arrived. I walked around the exterior in a manner I haven’t in ages. I ambled over to Shea Stadium home plate in the Citi Field parking lot. I’m surprised I still know where to find it, not at all surprised that I don’t believe I’ll find it, given that previous Mets management seemed intent on erasing 45 years of ballpark history when it opened its shiny edifice in 2009. Yet there it was, fourteen years since installation. People were walking by it as if it wasn’t sacred. Sometimes you’re just thinking about lines and security. I took off my cap and tapped the plate once. I used to do that on Opening Day. I haven’t been to Opening Day in a while.

You gotta believe I saw the sign. I wanted to check out the banners affixed to the third base side of Citi Field, having been delighted to find so many evocative ones on the first base side a few weeks earlier. There I saw a literal sign: 1973 NATIONAL LEAGUE CHAMPIONS, replicating the marker above the highest right field stands. 1973! Fifty years! Citi Field was welcoming me as it rarely welcomes me! I saw more neato banners, like one with Tom Seaver and David Wright embracing at the 2013 All-Star Game and another with Robin Ventura and Todd Pratt embracing in the aftermath of Game Five of the 1999 NLCS, though maybe Tank should have just kept running, though then there wouldn’t be a banner, would there? I shifted to the first base edge of the rotunda and saw, as I always do, the brick that celebrates my first date with the right woman, May 15, 1987, four days after we met. We celebrate May 11 every year like I unfailingly commemorate July 11 in my mind. It was as if 41 Seaver Way had been trimmed specially for me, a sensation I rarely if ever have. All this looking around, yet I saw I had ample time before first pitch in the middle of the day in the middle of the week in front of the ballpark. My mood was off the charts.

Then lines and security and being told I beeped, please walk through the metal detector again. Which I did, and didn’t beep. Somebody else searched my bag and told me, “you beeped, so you have to walk through the metal detector again.” Which I didn’t, because, as I explained, I just did all that. Oh, OK.

Impenetrable barrier breached, I was soon inside and upstairs. Promenade for the first time this season. I did a little more walking around I usually wouldn’t bother with. It really is nice up there, especially on a warm day if you know where to sit for a 1:10 game. I knew where to sit without realizing how much. My row, Row 8, in my section, Section 518, fronted a Long Island day camp group. That was another sign. I was at my first game, on July 11, 1973, because I was in a Long Island day camp group. This was a different Long Island day camp, but my proximity made me an honorary camper for the day, I decided. A happy camper.

Hundreds of kids in blue and white t-shirts. I’ve never related particularly well to individual kids, but they were at a Mets game and I was at a Mets game and I hoped at least one among the hundreds would look back fifty or so years from this date, July 20, 2023, and think, “it’s the 50th anniversary of my first Mets game.” Or maybe they were all veterans of Citi Field by now. The organization of the counselors and the campers was something to behold. Kids, naturally, want to get up and get things. The counselors were prepared for “merch” or food runs, taking turns taking whoever wasn’t glued to the Mets and the White Sox to buy stuff, but in groups. There’s so much more to buy at Citi Field than there was at Shea Stadium in 1973. I bought a yearbook then. I didn’t see one kid come back from the “gift shop,” as one girl called it, with a yearbook. That’s all right. I’m sure they all have Baseball-Reference bookmarked on their phones.

Kids by the hundreds can be loud at a ballgame. They’re supposed to be, even the future loners in a mood among them. The first fly ball they saw they greeted as kids in day camp groups a half-century earlier greeted the first fly ball they saw, like it was gonna be a home run. Of course it wasn’t, because it almost never is. Judgment of fly balls would grow keener as the day went on. Shrieking would be intermittent but not intolerable to adult ears, despite the sadists in the control booth posting a NOISE METER on the enormous video screen. Like these kids need to be told to GET LOUD. No, they’ve got that covered, thanks. They were in great voice, singing along with the day’s Ballpark Karaoke winner, “Stacy’s Mom,” and you haven’t lived until you’ve been enveloped in hundreds of prepubescent voices celebrating the fact that “Stacy’s mom has got it goin’ on.” With the Mets down five runs in the middle innings and the White Sox batting, they also brought and sustained an impressive LET’S GO METS! chant. Loner in a Mood’s rules of order specifies LET’S GO METS! is best deployed tactically, ideally with a Met at the plate, but I’m going to tell hundreds of kids not to be excited about the Mets? You don’t last 50 years going to games quashing succeeding generations’ enthusiasm. The only thing I told any kid, a girl sitting directly behind me, was “Alvarez is DH’ing” when she absorbed the home team defense and asked, with Mets fan awareness that made my heart soar, “Where’s Alvarez?” (Don’t think it didn’t pain me to casually use “DH” in a sentence in a National League ballpark.)

The girl didn’t respond and I decided to let her figure the rest out for herself. Thus, when Omar Narvaez stepped into the box, and she greeted his appearance with, “Who’s that?” and Omar the Infrequent announced his presence with authority via his first Met home run, it made for a delightful surprise. As did (for me anyway) Jose Quintana’s solid five-inning Met debut, despite a few balls falling in early, and David Peterson picking a guy off first in relief. The delightful surprises were few and far between down on the field, as the Mets fell behind, 6-1, by which time I was quietly hoping that if the Mets weren’t going to storm ahead (as I once saw them do, at Shea after looking hopelessly flat most of a midweek afternoon game against Chicago’s National League entry), they’d give up one more run and lose, 7-1, because it was the score they lost by at my first game. That would be a pair of How It Started/How It’s Going bookends for the ages. But the White Sox were held to six, and Pete Alonso shocked all of civilization with an RBI single, and it would be 6-2 before it was over.

Ah, I didn’t need those bookends, anyway.

Jeff McNeil did not beat out any of his myriad grounders for base hits, despite repeatedly making the SAFE! gesture with his arms as he crossed first; it might not be the winning move he believes it to be. Drew Smith was not the effective reliever he strove to be, though I’m happy to report that in a ballpark full of kids out for a good time, he didn’t have to convince himself they were yelling “DROOOO!!!!” after he surrendered four runs, because none of the kids bought a scorecard, either, and none of them booed. Trevor Gott’s 1-2-3 top of the ninth was one I had to take mostly on faith because I got up to beat the day camp traffic as the eighth ended, an homage to my camp group fifty years ago leaving early to beat the Grand Central traffic. But I wasn’t bolting the ballpark. I decided a day dedicated to throwing it back to Shea wouldn’t be complete without a stroll down the right field ramps, Ramp, singular, I guess. On our last trip to Citi Field together, Jason and I were still mourning the passing of the Shea Stadium ramps, especially after a rousing win. No rousing win would be forthcoming on Thursday, but the ramp seemed just the way to roll. I would take my time and take it into field level and position myself to stand and watch the Mets storm ahead or, probably, be extinguished before turning back into a commuter determined to make the 4:24 at Woodside. That bit of watching the final outs from downstairs with the train on my mind was something I think I last did in 2011. I’m now officially capable of nostalgia for Citi Field’s early days.

A little ramp bonus if you ever want to try and time it correctly: If you’re somewhere between the suite level and the field level, you can see the mound if you peek in at the proper angle, and maybe you’ll catch a strike or two on your way down. I watched Trevor Gott retire his last batter that way, as if I was stealing glances while standing on the 7 extension they tore down after the 2007 season, and it was likely my favorite pitch of the day. I’m always officially capable of nostalgia for anything that evokes Shea Stadium, as long as it isn’t a moldy hot dog bun. Unfortunately, the Mets were not capable of a rally in the bottom of the ninth, and they fell to the White Sox by the non-bookend score of 6-2. No scores of a losing nature are terribly delightful, even when the rest of the day is. And though they’re not my concern, good for the White Sox fans who trekked to Flushing and got one win in three for their troubles. Bill Veeck once more, on the team he owned twice:

If there is any justice in this world, to be a White Sox fan frees a man from any other form of penance.

I don’t suspect any pennants are coming to the South Side of Chicago or the Queens side of New York this season. Tommy Pham left the game with more groin aggravation. Starling Marte went on the IL with migraine miseries. We’re however many games out with however many left, behind however many teams who are in our way. But enough with the undelightful aspects of fandom in general, Mets fandom in particular and my fandom most of all. This was my once every 50 years day. Sharing it with the campers, some of whom may still be talking about it today even if it won’t necessarily be on their minds on July 20, 2073, made it a win despite the loss.

Mildly funny thing to me is I actually remember what I was doing on July 20, 1973, nine days after that first game at Shea. It sticks with me because there was something sticking in my mouth. I had the first wires attached to certain of my teeth en route to a full set of braces, a joy I’d carry orally for the next six years (if they had metal detectors at Shea in the ’70s, I imagine the beeping would have been incessant). That date sticks with me because it was the fourth anniversary of the first moon landing, July 20, 1969. I’ve always had a thing for dates, historical and personal. It’s apparently unnatural, based on a lifetime of continually being asked, “How do you remember THAT?” and not in any kind of admiring way. The sense that you’re different from everybody else will turn a person into a loner in a mood, whatever the mood. But that, I figured out more than 50 years ago, is what baseball is for. Baseball we do together, even if we sit alone. Camp groups drift apart. As long as there are Mets, Mets fans will always gather at a ballpark, whatever it’s called. I now have 708 instances — 402 at Shea + 306 at Citi — to back up my assertion.

I won’t be visiting an orthodontist to commemorate the 50th anniversary of my getting braces. Being over 60, I will probably be aware of many 50th anniversaries of things I’ve experienced in the years ahead, but I doubt I’ll make a day of many of them. Knock wood/brick, May 11/15, 2037, would make for a nice ballpark trip, whatever ballpark the Mets are playing in by then. But I don’t like to get ahead of myself. Ruminating about a 50th Anniversary Game about a year in advance is the uppermost extent of my speed. Less preferable result notwithstanding, the Mets and White Sox indeed did fine.

Thus, I judge the mood landing on July 20, 2023 an emotional success. Plus, I made the 4:24 at Woodside with minutes to spare.

If you like a good anniversary of a bad team, listen to National League Town’s salute to the 1993 Mets, who gave at least one fan a season worth remembering 30 years later. You’ll also learn why “section captains” have emerged as the fans-in-the-stands equivalent of Jeff McNeil constantly calling himself safe at first.

by Jason Fry on 19 July 2023 11:34 pm Finally!

The Mets got the Justin Verlander they paid $43 million for — the fireballer who made opponents look silly as a Houston Astro, the no-doubt-about-it Hall of Famer, the top-of-the-rotation ace. And what a difference it made.

I was there, in surprisingly good Excelsior seats behind home plate (a crummy year has some silver linings), close enough that I could see location and pitch speeds, instead of peering at distant stick figures and cheering or groaning based on how quickly and in which direction they had to run around. And I could see the White Sox had no chance against Verlander — none whatsoever. Verlander could do whatever he wanted with them, and so he did. It probably helped that it was a more temperate evening than it had been for Verlander’s last start, when he was woefully inefficient and ill-used by the Mets, with a rocky seventh wrecking his chance at both a shutout and a complete game.

Not biggie, since Verlander handed a four-run lead over to the bullpen with just three outs to get, which meant they didn’t have enough time to screw it up, as they almost managed to do in whatever the hell that was on Tuesday night. The Mets didn’t set the world on fire, doing most of their offensive damage through walks against a wild Touki Toussaint, that long-ago Atlanta Brave, but we’ll take some fortunate sequencing after a season that’s been mostly buzzard’s luck. Not to be a bringdown, but I’m more than a little worried about Pete Alonso, whose frustration is a flashing neon sign visible from the uppermost row in the Promenade. Alonso’s body language has always been crystal-clear — the Polar Bear would be advised to never, ever take up poker — but he looks draggy and defeated, as you might expect considering he’s perilously close to the Mendoza line. (To say nothing of Jeff McNeil, whose trademark rage has curdled into a constant, simmering dismay.)

Not ideal, but once again — they won. Amazing what good starting pitching can do, isn’t it?

* * *

The night was a little warm but nothing like the smothering evenings we’ve had of late, and I think I would have enjoyed myself at Citi Field even if the score hadn’t been so favorable.

Still, it gives me no pleasure to report that the non-baseball part of my night at the park was consistently off-kilter. It started when I went to get a Nathan’s hot dog and fries and a beer, only to discover that the beer taps were mysteriously offline, a development reported with the kind of world-weary, whatcha-gonna-do shrug that was standard operating procedure as Shea crumbled. I secured a Plan B beer somewhere else and was most of my way through my hot dog when I noticed that the bun was spotted with gray-green. Yep, I’d been served a hot dog in a moldy bun, and I’d rather not think about the part I’d eaten without inspection. Later, the problem was broken soft-serve machines, resulting in one stand having a strangely long line for ice cream, to the bafflement of its beleaguered attendants. (Please note that we were in the semi-restricted part of Excelsior that’s sort of a club, where one would expect things to work a little better even though there shouldn’t be a difference in experiences.)

The folks who run the Mets can’t stop the pitchers they pay from hanging sliders or make the hitters they pay live up to what’s on the back of their baseball cards, but it should be within their power to ensure that hot-dog buns aren’t moldy, ice cream machines dispense ice cream and beer taps actually have something in them. That doesn’t seem like to much to ask.

On the other hand, though … for once there was no “Piano Man” to bring down the mood. Would I eat a moldy hot dog bun at a game in exchange for not being subjected to the moldy hot dog bun of self-loathing confessional ballads? I’d at least think it over.

by Greg Prince on 19 July 2023 2:32 pm When your opponent puts double digits in the run column and you win, anyway…

When you record a final score in your favor that you haven’t posted since the final months of the previous century…

When the prohibitive favorite to lead your team in his signature category for a record-tying fifth consecutive season might be compelled to glance over his slumping shoulder…

And when your kooky line score hardly looks lonely when inserted onto an out-of-town scoreboard…

Then you turn to ABBA’s conversation with that Fernando fella for inspiration, for there was something in the air Tuesday night, and we’re not talking smoke from a distant Canadian fire.

The Mets won an 11-10 game, which is something they hadn’t done in 24 years, and when they did it on May 20, 1999 — propelled by a Robin Ventura grand slam home run (a feat he’d duplicate in the second half of that evening’s doubleheader) — it was a first. Those Mets birthed a Unicorn Score, which means that on Tuesday these Mets gave us a Uniclone Score at which to marvel. Any time you get a score the franchise has won with only twice, you simply have to pause and marvel, though it hardly felt like the only marvelous takeaway from the Mets edging the visiting White Sox, 11-10.

While New York (NL) was Eleven-Tenning Chicago (AL), the same act was being carried out in Cincinnati by the Giants over the Reds, and in Kansas City, where the Tigers were the high-rolling losers. What could be more breathtaking than processing THREE 11-10 ballgames on the same night? How about a game in which the winner and loser each scored more? That was the tale told in Atlanta via Diamondbacks 16 Braves 13 — and Arizona didn’t even top the run pool Tuesday night. The Cubs scored 17 in blowing out the Nationals by 14.

The Dodgers scored 10 in bopping Baltimore. The Guardians scored 10 in pasting Pittsburgh. The Twins scored 10 in smashing Seattle. The Padres were pikers, plating only 9 in torching Toronto.

Mamma Mia, that’s a lot of runs! My, my, how do you explain it? My pet theory is the fifth day after the All-Star break brought out a surfeit of back-end starters who hadn’t pitched in well over a week, and their rust showed. At Citi Field, the White Sox threw Lucas Giolito, who hadn’t gone in nine days. He was opposed by Carlos Carrasco, toeing the rubber for the first time in twelve days. Counterintuitive to the sense that a well-rested pitcher should be able to stay on the mound longer than usual, neither lasted long enough to qualify for a win.

Not that that was going to be a concern for Giolito, the rare opposing pitcher to fully enable the Mets in a first inning. The Mets scored five times out of the gate. Giolito lasted into the fourth, but whatever length he was providing the Sox wasn’t worth the bullpen preservation. The Mets were up, 7-2, when he departed, and then added another run charged to Lucas’s ledger.

Up 8-2 in the fourth! The Mets ahead from the start and never to trail! A laugher!

Funny thing is, no. Maybe not so funny a thing. True enough that the Mets led the game and were neither headed nor tied, but on a night like July 18, 2023, as evidenced by the plethora of runs from coast to coast, no lead that wasn’t gargantuan was quite safe. Carrasco waded into too much troubled water and the Mets needed Grant Hartwig to bridge the conclusion of the fifth inning. No win for Carlos, which only matters when you develop the sneaking suspicion that the laugher already in progress is about to be pre-empted so we can show you a nailbiter.

Oh, but let’s remember the good times. Tommy Pham hitting hard and running free of groin encumbrance. Jeff McNeil returning to something resembling offensive life. DJ Stewart becoming the 87th Met to hit exactly 1 home run as a Met (and making a case for more playing time so he can attempt to extract himself from the 1 Home Run as a Met list by belting another). Brett Baty going very deep to remind us he’s more than the guy who unsuccessfully circled under a popup on Saturday. And, most marvelous of all, Francisco Alvarez and his two home runs, giving the rookie 19 on the year, which is astounding for all sorts of reasons, none less so than Alvarez has pulled to within seven homers of Pete Alonso for the team lead.

Since Pete Alonso came up in 2019, no Met has finished a full season remotely near the Polar Bear in the home run category. Michael Conforto finished second to Pete by 20 four years ago. In 2021, Francisco Lindor was the runnerup by 17. Last year, Lindor took the silver medal again, finishing 14 behind Alonso. Even within the limited parameters of 60-game 2020, the race wasn’t particularly close: Alonso 16, Dom Smith 10, Robinson Cano 10. When Pete stormed forward this season, one could begin to pencil in a fifth consecutive team home run crown for our slugger-in-residence, which would tie him with Mike Piazza in Metropolitan slugging streak supremacy (Mike led the Mets in homers every year from 1998 through 2002; no other Met has outhomered each of his teammates more than three years in a row). Alonso blasted his 10th home run of 2023 on April 21. Hitting more home runs than all of the 1980 Mets loomed as a more likely challenge for Pete than fending off any 2023 Met.

Something might be gaining on you. Yet on April 23, Francisco Alvarez hit his first home run of the season, and from that moment forward, Francisco has outslugged Pete, 19 to 16 (he’s also pulled aside Lindor in the all-Francisco lane for the entire year). Alvy’s momentum has been a sight and sensation to behold. We’d be best off with each of the A&A Amigos cranking balls out of yards — or, in Pete’s case, maybe recording a few singles and getting untracked — but Francisco sneaking up on the dinger king of Flushing has been an unexpected surprise and, frankly, kind of delightful.

The White Sox sneaking up on the Mets as Tuesday night went along was less so, yet there were the Pale Hose, weaving serious business from a prospective laugher, closing gaps of 8-2 and 11-4 until the Mets found themselves clinging to a one-run lead in the ninth. The potential tying and go-ahead runs had reached third and second, with Tim Anderson, undergoing his own Squirrelish renaissance, at the plate, and David Robertson barely hanging on. Yet Robbie induced a fly ball to center that flew no farther than Brandon Nimmo’s glove, and there we had it: the 15th victory in Mets history that encompassed at least 10 runs for the losing side. That sort of thing last happened two years ago today, in Cincinnati (Mets 15 Reds 11); had never happened previously at Citi Field; and happened most famously on July 4 and 5, 1985 (Mets over the Braves, 16-13, the same score by which Atlanta lost Tuesday night, which is fun to mention again). In a better year, the ability to follow up a 2-1 win with an 11-10 win could be taken as some sort of sign. Taking them together as a pleasant pause from the otherwise desultory norm will do fine for now.

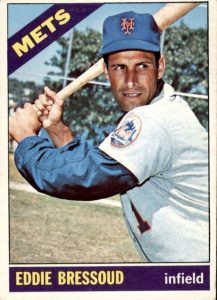

***A night chock full of homers launched in Queens and elsewhere seemed an appropriate setting to learn of the passing of one of stealthier sluggers in Mets history. Word emerged out of Northern California that Eddie Bressoud had died at the age of 91 last week. Eddie Bressoud was the Mets’ primary starting shortstop for one season, 1966, and in 1966, Eddie Bressoud set a home run record that wouldn’t be tied for more than 20 years nor surpassed for 40.

That’s not just power. That’s staying power.

When Bressoud — rhymes with ensue — arrived in New York, the most home runs any Met shortstop had hit in a season was two. Eddie shattered that mark and then some, knocking 10 homers over fences in ’66. It was a good year for a veteran player to set a standard as a Met, as the Mets, reinforced by the presence of several veterans, set their own standard. They were the first Mets team to finish above last place and with fewer than a hundred losses. Like 10 homers by one player in one year (remember, Alonso had 10 this year by April 21), winding up in ninth place by going 66-95 may not strike the uninitiated as an accomplishment, but progress was progress. In 1966, the Mets of Eddie Bressoud were progressing from the dregs of the National League to something somewhat less dreggy.

The right bat in the right place at the right time. Eddie wasn’t a building block in Flushing. He was filling a need for an established shortstop with a little pop while the good-glove youngster on whom the Mets had their eye for the position longer-term, 21-year-old Bud Harrelson, worked on his hitting in the minors. Bressoud thus succeeded slick fielding elder statesman Roy McMillan and kept the middle of the infield professional while Buddy summered at Triple-A Jacksonville, learning to swing from both sides of the plate (a career-altering course inspired by an incidental Spring Training encounter Harrelson had with a club executive by the name of Charles Dillon Stengel). Shortstops in those days for the most part were asked to field first and hit later, if at all. On the Mets, from Elio Chacon through Al Moran and McMillan, power was not part of the shortstop job description.

Bressoud reset that expectation during his one year as a Met. That record he set he took with him when he was traded to St. Louis before the start of the 1967 season. By then, Harrelson was ready to play short, which he did to great defensive effect for the next ten years, yet for all Buddy derived from his ability to switch-hit, he was never gonna be a home run guy. Nor were his part- or full-time successors Mike Phillips, Tim Foli, Frank Taveras, Ron Gardenhire, Jose Oquendo or Rafael Santana. It wasn’t until Kevin Elster, a Harrelson protégé, settled in as the regular shortstop that a Met who manned that position regularly matched Eddie Bressoud’s home run output. Kevin socked 10 homers in 1989, tying Ed. That remained the shared record until 2006, when Jose Reyes forever redefined the notion of production by a Met shortstop, hitting 19 homers.

Mets fans of a historical bent recognize Bressoud’s name for another reason Eddie came up to the majors with the New York Giants in 1956. By joining the Mets a decade later, he became the first alumnus of the departed New York National League ballclub to play for their successors. One of the enduring myths of Metsology is the Original Mets were stocked with old Dodgers and Giants to draw in the fans left abandoned by the teams that occupied Ebbets Field and the Polo Grounds. That’s half-true. Lots of Dodgers: Hodges, Zimmer, Neal, Craig, Labine briefly, Snider in the second year. No Giants, though, at least not in the players sense.

You certainly had Giant DNA on the premises. You had Mrs. Payson, who owned a sliver of the Giants in New York and couldn’t just let her fortune sit in a vault when there was a chance to replace them once they bolted. You had Ol’ Case, who starred in World Series play for the Jints in the 1920s but whose scampering around the bases days were through by 1962. You’d have old catcher Wes Westrum serving as Casey’s coach starting in 1963 and, eventually, the team’s manager when it leapt from tenth place to ninth. You had 1954 World Champion Giants ace Johnny Antonelli demurring when the Mets purchased his contract in 1961, choosing to retire instead. And, shoot, you had the Polo Grounds welcoming the Mets to Upper Manhattan as the neighborhood’s new home team. But it took until 1966 for an actual former NYG to take on the identity of NYM. That was Bressoud.

The second and last former New York Giants to play for the New York Mets wouldn’t show up for another six years. His name was Willie Mays. If it were up to Mrs. Payson, Willie would have been a Met from the beginning. If it were up to Mrs. Payson, Willie and the Giants would have never left.

In the ’61 expansion draft that stocked the Mets so (ahem) abundantly, it’s pretty well known that the Mets did pick a San Francisco Giant with their first pick, catcher Hobie Landrith. Hobie had his own mythology. Less known, outside of Houston maybe, is that the first pick overall, once the Colt .45s won the coin flip, was Eddie Bressoud. By then, Bressoud was, like Landrith, a Giant of the SF variety. The future Astros grabbed him, but then traded him to Boston for Don Buddin. Boston got the better of the deal, as Eddie would go on to reach the All-Star Game for the Red Sox in 1964. The site of that Midsummer Classic was Shea Stadium. From the American League bench, Eddie perhaps made a mental note that he liked the joint and wouldn’t mind getting to know it better. That opportunity arose prior to 1966, when the Mets traded their erstwhile .300 hitter Joe Christopher to Boston to get Bressoud.

“My wife always said that was the most fun place we ever played,” Eddie told author Bill Ryczek for his 2008 book about the Mets of the 1960s. “She described herself as a participant rather than a spectator. There was an awful lot of excitement in the ballpark all the time. We were being beaten by eight or nine runs in the seventh, eighth or ninth inning, and the ‘Let’s Go Mets’ chant would start up. You’d feel, ‘Golly sakes, they’re really with us’ and you’d try a little harder.”

The Mets weren’t hopelessly out of games as often as they had been previously during Bressoud’s lone year in orange and blue. If he remembered it fondly, he deserved to be remembered just as fondly. On his Ultimate Mets Database fan memories page, it appears his relatively brief detour through Shea Stadium left an impression beyond his longstanding shortstop home run record. The best comment attesting to his legacy:

Eddie drives up to the players lot behind the Met bullpen. Kids would hang there early and scream for tickets as the players pulled up. Eddie reaches out with 2 tix and says, “Don’t sell these. I’ll be watching for you.” My friend and I go inside and we are right behind the Met dugout 3 rows back. Eddie starts that day and first time up he looks back to see if we’re there. We wave and yell “hit a homer, Eddie!” Of course he does and we go nuts. He comes back to the dugout, looks at us and smiles. For two 15-year-old kids, it made our decade.

Eddie spent more than a decade in the big leagues, winding up with the Cardinals in a supporting role as they won the 1967 World Series. The Mets had sent him to the Redbirds in exchange for second baseman Jerry Buchek. Harrelson was going to get his shot at short, and that would work out pretty well. Meanwhile, the rest of Bressoud’s life, in and out of the ranks of pro ball, worked out more than splendidly. “He was a true family man,” Ed’s son Steve told the Vallejo Times-Herald, and noted his dad took it upon himself to be “an ambassador for the Giants, no matter where he went. He would see someone wearing a Giants hat and instantly strike up a conversation with him.”

Bressoud may have been a lifelong Californian, but he carried a certain New York distinction beyond the Mets-Giants connection. Few are the people who can any longer say they registered at least one regular-season base hit at the four primary 20th century ballparks of New York City. Eddie was one of them. He started out at the Polo Grounds and got a hit; he showed up in time to play a little at Ebbets Field and got a hit; his trade to Boston positioned him to visit Yankee Stadium, where he got a hit; and then came to the trade back to the National League and his introduction to Shea Stadium, where he not only got hits, but made a couple of kids’ decades. Well before Interleague play, when even trades between the NL and AL were infrequent and free agency was nonexistent, players didn’t really move much between leagues, so the chance to collect a hit in each of those four stadia was fairly uncommon. That Bressoud pulled it off by a) playing home games at the Polo Grounds and b) playing home games at Shea Stadium without c) having played home games at the Polo Grounds as a Met makes it all the more noteworthy.

To the best of my calculating, the 4 Borough Hit Club went out of business once Hank Aaron and Frank Robinson retired in 1976. It was already pretty sparsely staffed by the time Bressoud finished playing in 1967. Its survivors today include Ozzie Virgil, Sr. (one of the nine remaining living New York Giants) and Original Met Felix Mantilla, a teammate of Bressoud’s in Boston. There may be a few others I didn’t detect when researching the matter, but there can’t be many still around. You had to play well enough long enough to span multiple eras and be wanted on multiple teams, and to be able to claim the distinction more than a half-century later, you had to have lived quite a life after baseball.

Eddie Bressoud did all that.

by Jason Fry on 16 July 2023 10:26 pm Here’s a no doubt scintillating look behind the curtain at Faith & Fear headquarters: We divvy up games by having whoever’s more engaged/worried about the next week or so send out an email proposing a more or less equal division of labor:

Jace Th, Sat, Tues

Greg Fri, Sun, Wed?

That sort of thing. Then there’s some horsetrading, based on whoever’s stuck with non-baseball plans, actually attending a game and so wanting to chronicling it, or otherwise demonstrating some compelling reason to recap something or beg off said duty.

Which brings us to the last such email, from Greg: Fri, Sun, Wed for me; Sat, Tues, Thurs for him?

Friday was fine. Wednesday was fine — in fact I was going, as the Mets had scheduled a giveaway of Topps cards, and a little glance via TV ads suggested they were some unique spinoff. But Sunday was no good — I’d be in a kayak for the entirety of the game as scheduled.

Sure! I replied.

Why did I do that? In part because my blog partner has put up with waaaaaaay more of his share of my boozy dinner plans, vacations, conventions and miscellaneous running around over the nearly two decades we’ve been doing this. But I also did that because it’s only the 2023 Mets, and they’ve forfeited the right to dictate my schedule. When things are good the Mets’ schedule is what I arrange the rest of life around, if possible. Hell, when things are merely “not catastrophic” that’s also true.

It would be a stretch to call things “not catastrophic” right now. The team looks variously too old and too young, too tightly wound and asleep at the switch, and they’re failing both the quantifiable and the un-.

So I said Sure. Honestly, the exclamation point was more than the Mets deserved.

Friday night I managed to work myself into being fleetingly outraged about the negligent way Justin Verlander was handled. Saturday I was out seeing a rock concert and tuned in after the show just in time to hear Mark Canha, Brett Baty and Luis Guillorme string together three of the most pathetic at-bats of a season that hasn’t exactly been lacking in lowlights.

This was not really the kind of thing to suggest one ought to be devoted to one’s duty.

It rained cats and dogs Sunday morning. No kayaking, but also no Mets. The game was pushed back to 5:10 pm, which removed the no longer relevant kayaking conflict but put the rescheduled game up against my mom taking us all out for Emily’s belated birthday dinner.

In a non-catastrophic year this might have meant an earbud in whatever ear was most removed from the conversational center of gravity, or Gameday ticking along in my lap, or at least surreptitious check-ins while dishes were getting cleared and new drinks were arriving.

But you know what? I didn’t look at my phone once. When we were in car going home, my kid told me that the Mets had won. Great, I thought, and it was an hour or so before I got the details of a game that sounds a lot like other 2023 Met games. Max Scherzer pitched very well (that’s at least kind of new), the Mets didn’t score for him (not new), there was a bullpen lapse that threatened to ruin everything (also not new). The difference was that this time no one got hit in the face with a pop-up, or otherwise failed egregiously in public: Guillorme poked a ball down the first-base line in the bottom of the 10th to bring home Baty as Rob Manfred’s phantom runner, and the game was won.

Like I said, great.

The Mets are off Monday. I’ll watch with my mom Tuesday. I’m going Wednesday and will recap. So I’m not going to pretend the last two nights’ lack of attention is some principled protest or doofy fan walkout. I’ll be watching Tuesday and Wednesday, but that’s because doing so suits my schedule. The Mets are welcome to demonstrate that they deserve more attention than that, but as it stands, I think I’ve got things calibrated correctly.

by Greg Prince on 16 July 2023 12:35 pm One of the greatest baseball anecdotes ever repeated flew off the bat of Pittsburgh Crawfords catcher Josh Gibson, who was reported to have hit a ball out of Forbes Field “so high and so far that no one saw it come down,” leaving the umpire no choice but to call it a home run without definitive evidence. The next day, legend would have it, the Crawfords were playing in Philadelphia when “a ball dropped out of the heavens and was caught by the startled center fielder on the opposing club”. The ump’s response? He pointed to Gibson, and told the slugger, “Yer out — yesterday in Pittsburgh!”

In that spirit, congratulations to de facto New York Mets Player of the Week David Robertson, who was awarded a win for his pitching from April 27 on July 12. A surprisingly long-simmering official scoring change shifted the W in what was nearly a Met debacle at Citi Field — the Mets led the Nats, 7-3, entering the eighth; trailed the Nats, 8-7, by the middle of the inning; yet righted their ship, 9-8, in the bottom of the frame — from Brooks Raley to Robertson. Raley had succeeded Tommy Hunter to the mound in the top of the inning in question after Hunter had hit two batters and was victimized by an error, then allowed each of those runners plus a couple more to score, with a CJ Abrams grand slam the temporary crushing blow. When the Mets came back, the stubbornly reflexive act was to call Raley the pitcher of record on the winning side, and when Robertson set down the Nationals in order, David was credited with a save.

Official scoring changed its mind 76 days after the fact, with Robbie deemed the more effective reliever than Raley and therefore the only one worthy of a win, whatever you consider the worth of pitcher wins these days. David Robertson now carries a record of 3-2 rather than the 2-2 he brought into the break, albeit with 12 saves instead of 13, perhaps not as desirable to a closer for whom saves are recognized as currency of the realm.

Nevertheless, we applaud David Robertson for having notched the only win by any Mets pitcher in more than a week, even if it required more than two months for it to arrive. We also congratulate the amiable veteran for not pitching in any of the Mets’ past four games, a.k.a. the losing streak that has straddled the sport’s midsummer vacation period. There are few 2023 Mets we don’t currently associate with losing efforts. Let’s cherish David Robertson’s ability to mine a W when nobody was looking before we turn our attention to valuing whatever potentially useful minor leaguer the Mets might acquire from a legitimate contender in exchange for David’s services.

A pat on the back is order as well for Kodai Senga, who has developed into a true Met ace. He pitches well, and his team doesn’t score for him. There’s a fellow not doing much in Arlington, Tex., these days who can tell him, through the multilingual skills of interpreter Hiro Fujiwara, how rewarding that can be. On Saturday night, Kodai was true to emerging form, no doubt helped along by the oodles of rest of he received from a) the All-Star break; b) not pitching in the All-Star game to thoughtfully preserve his arm for league competition; and c) a 46-minute pregame rain delay that provided him an extra three-quarters of an hour of rest. Senga hasn’t really adapted to MLB’s every-fifth-day rotational norm, so why forsake him his ideal recovery time? Not a lot of Mets are getting it done as the second half gets underway. Huzzah for a Met who is…however long it takes for him to resume doing it.

Kodai threw six innings, allowed four hits and one walk, struck out nine, escaped a bases-loaded jam, was tagged only for a Mookie Betts opposite field solo homer and left engaged in a 1-1 tie enabled by Brandon Nimmo’s fourth-inning blast that flew clearly over the center field fence with nobody on base. (One wonders how replay review would have handled Josh Gibson’s 1930s cloudbusters.) The Mets hit other balls hard or far off Dodger starter Tony Gonsolin, but they seemed to find gloves, as balls hit by Mets do when the Mets as a whole are being the way these Mets can be.

The tense pitchers’ duel aspect of Saturday night’s contest vaporized over time, just as the 2023 Mets have. The culprits felt familiar: the opposition running game playing havoc with a reliever whose occasional glances at first are no more than an optic tic; a somewhat challenging infield play that had to be made but wasn’t; a play one wouldn’t think couldn’t not be made but wasn’t; and a complete paucity of offense. Met losses are a veritable smorgasbord of indigestible possibilities.

In the eighth, Adam Ottavino, who must have registered as a conscientious objector to holding runners on when he signed his first professional contract, didn’t pay discernible or at least efficacious heed to Max Muncy on first. Muncy thus took off like lightning despite rarely being mistaken for a streak across the sky, while J.D. Martinez was in the process of poking a ball into right field. Runners were on first and third with one out. Pete Alonso fielded the forthcoming bouncer from David Peralta. Pete could have thrown home to cut off the go-ahead run Muncy represented after streaking from first to third. Alonso threw to second, instead. Not a terrible choice, for if the throw to second is on target, because if it is, it sets up a double play, and the inning is over, and the game is still tied.

The throw to second was not on target. Francisco Lindor had to pull it down to keep it from sailing to parts unknown. Martinez was out at second, but Peralta beat the relay at first. Muncy, natch, scored. The Dodgers were ahead, 2-1. Ottavino proceeded to put two more runners on base but wriggled from danger. Danger became the Mets’ middle name (briefly supplanting “York”) in the bottom of the eighth when Tommy Pham pinch-walked and Francisco Alvarez singled, together accounting for one-third of the Mets baserunner contingent to that point. Earlier, you had that Nimmo homer in the fourth, an Alonso single way back in the second, and two Lindor walks. The single and the walks were erased on double plays.

The fifth and sixth Met baserunners of the game, Pham and Alvarez, would be the last of their kind. The three Mets who came to bat following their exploits devoted eight pitches to making three outs, with Mark Canha popping up the first pitch he saw as a pinch-hitter, Brett Baty striking out on three pitches, and esteemed count-worker Luis Guillorme striking out after four. Futile became the Mets’ first name (nudging ahead of “New”).

A splendid start cast into no-decision territory, a key double play attempt that became a run-scoring fielder’s choice, zero clutch hitting, and even less hitting in general all became obscured by Saturday night’s highlight play in the top of the ninth, if only a highlight comparable to those contained in the home team clips Marv Albert used to show when he anchored the sports on Channel 4 and called them lowlights (which I found incredibly clever when I was seven years old). Baseball coroners might wish to exhume this lowlight when they are compelled to investigate the death of the Mets’ 2023 season.

Muncy, the Dodger who from a distance resembles Justin Turner if you tossed Turner and too many ColorCatchers in the washing machine, pops up a rally-pausing pitch from Grant Hartwig. One is out. Runners are on second and third. The Dodgers are bearing down with insurance run possibilities a gecko would gladly endorse, but a popup to third is a popup to third. If Max Muncy doesn’t run like Max Carey (few have; Carey stole 738 bases), he also doesn’t necessarily hit balls so high and so far that no one sees them coming down à la Josh Gibson (Muncy has smacked 165 career homers, but legends are legends). A popup to third with one out should have “second out” written all over it, presuming you can make out the printing in the misty night atmosphere above Seaver Way.

Brett Baty did not have that capability. This particular product of Rawlings Sporting Goods must’ve got caught in one of those “gusts from the gods” that vexed Kevin Costner as Roy McAvoy in Tin Cup. Getting it caught in Baty’s glove was going to be more difficult than imagined by the home viewer. Ye olde horsehide swirled from foul to fair. Baty morphed from promising rookie we all embrace into the second coming of Luis Castillo. Buoyant Brett in an instant became Lost Luis as he dove onto the infield dirt, grasping for a miracle. The last one apparently left Citi Field with Dead & Company. The ball bounced to the ground, then, in a desperate attempt to add injury to insult, clanked off Baty’s face. Another Dodger run crossed the plate. It wouldn’t be the last one in what turned into a 5-1 Met defeat we can only hope a diligent official scoring oversight board will overturn eleven weeks from now.

Your New York Mets, if you still care to claim emotional possession of them, are now 42-50, or one game better than their predecessors from four years before, a crew invoked here for the benefit of the kind of good-hearted lunatic who can conjure a future for the contemporary bunch. The 2019 Mets lost their first game out of the All-Star break, looking as dead as a company of ballplayers could, falling to 40-51. Then they won their second game, touching off a probably already forgotten spurt for the ages. The 2019 Mets won 46 of their final 71 games — more or less the pace cockeyed optimists have plotted in their wildest dreams for the 2023 Mets — and injected themselves into the Wild Card race well into September. It took more than a hundred games for us to invest any faith in the ’19 Mets at all. By Game 116, the night when shirts were torn with force, fury and glee, we believed anything was possible. Succeeding events would disabuse us of that notion, but they gave us a helluva show, and if MLB’s powers that be had been as generous with playoff spots as they are now, we might have gone somewhere besides home that October.

I don’t intend to suggest 2019 presents an applicable precedent for 2023. I’m simply providing a less loaded yet still somewhat satisfying example besides 1973 to hang your aspirational hat on. Your aspirational hat is probably best stored in a cool, dry place, but some Mets fans never give up, and that strand of our DNA should not be allowed to curdle into extinction. This season will soon enough, if three-and-a-half hours later than scheduled, with first pitch today reslated for 5:10 PM in deference to the impending awfulness forecast to assault Flushing.

The weather, I mean. To what did you think I was referring?

by Jason Fry on 14 July 2023 10:56 pm By one measure, Justin Verlander looked pretty good after facing 16 Dodgers on Friday night at Citi Field to kick off the second half of the 2023 season: He hadn’t allowed a hit, keeping the Mets even in a 0-0 pitchers’ duel with Julio Urias.

And if that’s the extent of what you saw, well, maybe there’s a position available for you with the Mets braintrust, to stretch the definition of a word to the breaking point and possibly beyond.

Because Verlander had been maddeningly inefficient, as he has been so often this year. With one out in the fifth, he’d thrown 77 pitches — on a sweltering night, as an old power pitcher forced to deal with the relentless pace of the pitch clock. (Mark my words: This is going to be one of the lessons learned from the introduction of Rob Manfred’s new toy, with the Mets’ 2023 blueprint front and center in explanations of what no longer works.) What Verlander had done so far in Friday’s game strongly suggested he’d wind up trying to finish the fifth north of 90 pitches. And the combination of the heat and what Verlander had done pretty much all year strongly suggested viewing that at least as a yellow light and probably as a flashing red one.

But the Mets bullpen was quiet. And it stayed quiet as Verlander lost his command, walking the next three guys and indeed bringing that pitch count above 90. Eventually Jeremy Hefner was sent out to try and offer some counsel and Mets relievers started milling around and limbering up, but it was too late: The Dodgers’ best hitters were coming up and knew they had Verlander on the ropes with no chance of rescue. In a four-pitch stretch Mookie Betts singled and Freddie Freeman doubled and the game was lost. On my couch, I was sputtering in rage, not so much at Verlander having failed but at how he’d been fed into the meat grinder. Had Buck Showalter really not seen that coming? Was anyone in the dugout paying the slightest bit of fucking attention?

After Verlander imploded the game degenerated into a farce, with Met hitters doing literally nothing and Met relievers walking guys and giving up hits and trudging around disconsolately while a weary crowd booed halfheartedly, disgusted by a game that had gone wrong pretty much from the jump. Let the record show that the Mets’ leadoff hitter, Brandon Nimmo, hit what was called a home run, then (correctly) revised into a double, and that was the only hit the Mets tallied all game. Their 1-0 lead was a phantom that lasted about 90 seconds.

What a way to start the second half: The Mets not only played badly but also looked badly led.

Look, baseball players fail all the time — it’s a cliche of the game that a hitter who fails seven times out of 10 is considered All-Star quality. The game can be capricious bordering on deeply unfair, and the ebbs of a season — those teeth-grinding stretches where nothing goes right — are brutal.

But there’s failure and there’s setting up your players to fail. What happened Friday night struck me as inattention bordering on negligence. And if that’s the way a team’s going to be run, why in hell should anyone watch?

by Greg Prince on 12 July 2023 10:43 am On July 11, 2023, the National League defeated the American League in an All-Star Game for the first time since 2012, which added a flourish to the 50th Anniversary celebration of this correspondent’s first game at Shea Stadium, which occurred on July 11, 1973. To commemorate the seminal occasion, I dug into the Faith and Fear archives to repost my original report from July 12, 1973, which, of course, ran here exactly fifty years ago today. I hope you longtime readers will enjoy this trip down memory lane.

Well, it’s finally happened. I’ve been to Shea Stadium. For the first time, I’m able to tell you more than what a Mets game looked like on television or sounded like on radio. I had all five senses going for me on Wednesday, courtesy of Camp Avnet, where, as you know, I’ve been whiling away my days between fourth and fifth grades. Camp Avnet is kosher. I’m not, but I’m willing to go along with the program if it finally gets me to a Mets game. As you know from my continual grumbling on the subject, I was supposed to make my Flushing debut last September, but I got a cold, and my pediatrician told my mother it wasn’t a good idea to have me sit outside for several hours. My pediatrician’s office is stale with the smell of too many pets. She must not understand the benefit of fresh air.

The cold went away, no thanks to the family staying home and me not seeing the Mets beat the Phillies that Saturday, September 23, 1972, not that I’m obsessing on it nine-and-a-half months later. Maybe one of these days I’ll forget the date of what was supposed to be my first Mets game. Give me fifty years and get back to me.

My mother signed me up for this day camp because me hanging around the house, as I tend to do in summer, is considered not good for me. Where was this concern for getting me out of the house last September 23? Anyway, Camp Avnet, despite its dietary restrictions and parochial school-style interludes (it’s hosted by what’s usually the Hebrew Academy of Long Beach) has been all right thus far. We swim pretty much every day. On Mondays we head over to the Long Beach Bowl, where I must say I’m getting pretty good at an activity I’d only known about from watching Fred Flintstone do it. And we have trips beyond the bowling alley scheduled here and there. We’re supposed to go to Coney Island for go-karts at some point, Grant Park in Lawrence for paddleboats and, oh look, Houston Astros at N.Y. Mets on Wednesday, July 11.

No offense to the go-karts and the paddle boats and the bowling and the chance that the Red Cross might foolishly certify me some kind of junior life saver by the end of August. I cheerfully assented to be transported to Camp Avnet every weekday morning this summer because I saw that little trip planned. All I had to do was keep showing up and not catch a cold, and I could break the most vexing streak to which I have been party since discovering the Mets four summers ago, the one in which every day I love a certain baseball team, yet I never go to see them.

It’s over! I’ve done it! I’ve been to a Mets game! It has happened!

Hey, I’ve been there! To be fair, that’s probably more excitement expressed over Wednesday’s game than there was during it, even by me, partly because a 7-1 loss to the Astros simply isn’t very exciting, even if it’s taking place before your eyes, ears, nose and everything else; and partly because I realize I’m more comfortable when I’m playing it cool at the ballpark. Not that I had any ballpark experience before yesterday.

I’m sure you have plenty of questions befitting a ten-year-old who’s just been to his first major league baseball game, so I will try to conceive of what they might be and also answer them.

Really, it’s no trouble at all. I like to write.

Q: Did you catch a foul ball?

A: Don’t be misled by what you see on Channel 9, where happy fans are grabbing foul balls in the middle of seemingly every at-bat. That doesn’t happen everywhere at Shea Stadium, especially not where we were sitting. They don’t put camp groups in the seats closest to the field. Besides, our counselor, Marvin, warned us away from bringing our gloves. “You’ll just lose ’em,” he warned. Nice show of faith in the responsibility of your charges, Marvin, but we followed the presumably well-meaning advice and stashed them in our cubby holes before heading to Shea.

Q: Did you get any autographs?

A: Again, I’d caution you to not blindly buy into whatever you’ve seen on TV as the norm. No, no autographs. We were too far from the players, and, besides, Marvin says you have to be clever to get an autograph. He told us about how he came to the All-Star Game in 1964, the year Shea Stadium opened, and saw Willie Mays sitting on the team bus. He ran up to the window with a pen and a $20 bill. Willie signed. I’m ten years old. Do I look like I have a spare $20 bill? Hell, in school they make us use pencils. So, no, no valuable autographs from Willie Mays, but I did see Willie start at first base for the Mets, so I can always tell people that.

Q: How did you get to Shea Stadium?

A: How do day campers get anywhere as a group? We went on a school bus. Don’t ask me the route. I wasn’t paying attention out the window other than at the clouds, hoping it wouldn’t rain. With Marvin holding court about his autographed $20 bill, I don’t remember which highways or parkways we took, I just know that we got there. I am moved to wonder that, if I ever get to go another Mets game (assuming I didn’t catch my death of cold yesterday), how I would find my way. I understand the Long Island Rail Road has trains that go to Shea. I’ll have to check that out sometime.

Q: Did you get a yearbook?

Do you honestly think after parts of five seasons listening to Lindsey Nelson, Ralph Kiner and Bob Murphy imploring me to add the official New York Mets yearbook to my “baseball library” that I wasn’t going to avail myself of the in-person opportunity? Last year I had to ask my mother to write a check for, I think, $1.25 (including 50 cents for shipping and handling) to have it mailed to me. Seventy-five cents of my hard-earned allowance was jingling in my pocket for this purchase, and I was not displeased by the investment. I’m learning so much from the 1973 yearbook. For example, did you know Ed Kranepool was once an All-Star? It’s true! I am, however, kicking myself for not buying what they call the program, which it turns out is the same as a scorecard. The program has even more information about the Mets in it, which is a great thing. I mean it’s not like there’s some machine you can turn on, press a few buttons and get all the Met information in the world from, so, naturally I want to build my baseball library.

Q: Did you get a hot dog?

I see we’re back to those stereotypical TV images. No, no hot dog for me. Remember, I was traveling with the kosher day camp. God forbid we go off the culinary reservation for an afternoon. Camp Avnet packed box lunches featuring salami sandwiches. I hope they were in a cooler of some sort before they got to us. Judging from my reaction to them hours later, I would guess no. A little ice cream would have gone great, and lord knows they sell ice cream at Shea Stadium (little cups, wooden sticks), but try to slip that shanda by Marvin the counselor when the special of the day is sitting-out salami.

Q: What’s that big scoreboard look like in person?

Man, that thing is huge! I can’t imagine a bigger scoreboard in a baseball stadium. It even brought good tidings before the game started, announcing Jim Fregosi had been sold to Texas. Too bad it didn’t also announce Nolan Ryan would be coming back from California, but you can’t have everything. You can’t even have ice cream when you’re rolling with Camp Avnet.

Q: Did you see any home runs?

One, hit by Lee May, who I don’t have to tell you does not play for the Mets, so there goes the chance to get weepy-eyed over another of those iconic baseball images you hear so much about. I mean, it went over the fence, yea, but it also made the score Houston 5 Mets 1, so, at the risk of being more parochial than the Hebrew Academy, boo. I will tell you it took me a couple of innings to adjust to the notion that not every fly ball is a home run. From the Upper Deck at Shea Stadium, they all look so high that you think they’re all going, going, gone, but, no, they come down and are caught. Except for the one Lee May hit.

Q: Did the Mets win?

What are you, a wise guy? It’s the day after. You don’t need me to tell you that yesterday, Wednesday, July 11, 1973, the Mets lost to the Astros, 7-1. Jerry Koosman gave up nine hits and six runs, five of them earned (not that I’ve quite figured out exactly how that’s calculated; cut me some slack, I’m only ten). Seaver and Matlack had been so good beating Houston the two games before. Maybe one of our really good pitchers was due for a letdown. Jim McAndrew relieved Jerry and gave up two more runs. Felix Millan went 4-for-4 for us, but remarkably his three singles and one double led to no runs. Bud Harrelson drove in one run, or as many as Tommie Agee did. Agee is now an Astro. Rich Chiles, for whom Agee was traded last winter, was nowhere to be found despite the official yearbook telling me Rich was “Houston’s second choice in 1968 free agent draft after completing brilliant high school career as a 4-letter man in baseball, football, basketball and track.” I wonder what it’s like for Agee being managed by Leo Durocher, like if they ever get mad at one another about 1969. Ah, that was four years ago, a veritable lifetime, or approximately 40% of mine.

Q: Did you stay for the whole game?

When your ride home is somebody else’s bus, you leave when they tell you to leave, so, no, I did not stay for the whole game. I should have seen the writing on the wall, even if the writing was in Hebrew and I had to read it from right to left, when Marvin told us that on last year’s Camp Avnet trip they left in the eighth inning and listened to the Mets complete their win on the bus back to Long Beach. The game didn’t take even two hours this year, so I don’t know what the rush was, but then again, i don’t drive the bus.

Q: Do you think the Mets are any good?

That, as I’ve heard said by adults using a reference I’m not sure I understand, is the $64,000 question (plus whatever it is for shipping and handling). I mean, come on, these are the Mets! They’re good, right? I’ve only been watching them since 1969, but I think about what I’ve seen: a world championship and three third-place finishes. This team still has many of those players, and even if some of them have been injured, you look at them and you wonder how the Mets are 36-47 and in last place, 11½ games behind the stupid Cubs. I guess a lot of what ails us, besides ailing players, is the guy I didn’t get to see much of yesterday. Tug McGraw pitched the eighth and ninth and was perfect. Less perfect was we were on the bus by the time he was done. Totally imperfect would describe Tug this year. Maybe if he can start throwing his screwball the way he always has we’ll be better. Weren’t we 9½ behind the Cubs in August in 1969? (That’s a rhetorical question. You and I know we were.) Can’t we make up that much, plus an extra couple of games, with another month to do it in 1973? (I’m not sure if that’s a rhetorical question.)

Q: Do you think the Mets should fire Yogi Berra?

I know other teams sometimes fire their manager. Durocher became Astros manager last year because Houston fired Harry “The Hat” Walker. I think we’re legally required to refer to Walker as Harry “the Hat” at least once per mention. But I don’t think it’s all Yogi’s fault. The Post has been running a poll, asking if the blame falls on Berra, Bob Scheffing or M. Donald Grant. Maybe it’s a team effort, and based on his yearbook photo, this Grant guy — the “chairman of the board,” whatever that is — doesn’t inspire a lot of confidence, but whatever happened to patience? Cripes, I’m ten, and I seem to have more patience than most sportswriters. Leave it to a politician to make the most sense on the subject. I read in the Daily News that Brooklyn Borough President Sebastian Leone (and, no, I’m not sure what a borough president is, living outside the five boroughs as I do), was also at Shea yesterday to tell Grant to, in so many words, leave Yogi alone: “Yogi’s a warm human being, and he certainly deserves more dignity that Mr. Grant has shown him.” Maybe this Leone guy oughta run for actual president.

Q: Do you believe the Mets will get better?

Given that My First Game Ever at Shea Stadium figures to endure as a momentous event in my life, I asked my father if he could find me as many newspapers as he could so I could read everything written about it from throughout the Metropolitan Area. Good ol’ Dad came through, and got me The Record, one of those New Jersey papers at some newsstand in the city. In an article by Ron Drogo, it says, “there has been a noticeable change in the mental attitude of the team. A pep talk from board chairman M. Donald Grant, a couple of close wins over the Houston Astros, and the thought of a healthy team seem to have lifted the Mets’ spirits. Even yesterday’s 7-1 loss to the Astros and visions of a 13-game road trip that begins in Cincinnati tomorrow night didn’t seem to dampen their new-found optimism.” Mr. 4-for-4 himself, Felix Millan said in the Herald-News, from Passaic, “I still say this is a hell of a club.” I’m impressed they let Felix curse in a newspaper, but who knows what goes on over there in Jersey? Millan also noted that “McGraw’s screwball was good today,” which I appreciate knowing, having been absconded with to the bus too early to make that judgment for myself. “Yes, I threw some good ones,” Tug affirmed, even if it was in a bit of a mopup role, which the former All-Star and perennial Fireman of the Year candidate swore he didn’t mind pitching in. Listen, if the Mets can be upbeat after the 1973 they’ve had so far, and Tug McGraw can be upbeat after the 1973 he’s had so far, I guess we’ve got to believe.

by Greg Prince on 10 July 2023 9:57 am If you were beginning to worry that the All-Star break would impede the Mets’ gathering momentum for a push toward playoff contention, rest easy this week. There is no momentum. There will be no playoff contention.

All provisional prognostication is subject to change with the emergence of the next six-game winning streak, but by the time the Mets win six games in a row again, the All-Star break and the success that briefly preceded it before disappearing amid a lost weekend will be a faded memory — though should they somehow confound expectations and bolt from the “second half” gate winning six in a row to give them twelve of their last fourteen and make us all look like ninnies for giving up on them so soon, mazel tov. When we’re sure our team is sunk and they upend our certainty by rising to the surface and then some, we couldn’t be happier to be wrong. Our mood relative to the Mets is subject to change, too.

But we’re not going to be wrong. This ballclub’s brief peek at the light at the end of the tunnel revealed too much glare for them to handle. It’s dark in there again, likely for good in 2023.

Bill Parcells is oft-quoted on the subject of your record directly reflecting who you are. The Mets are a 42-48 baseball team. Moreover, they are what their Games Behind status says they are. After playing as well as they have all year for six games, before playing versus the Padres as they have more typically for the next two, they sit seven games behind the third-best non-first place record in the National League, with more teams than it is worth counting between them and that final postseason qualification slot. Had they gone into the All-Star break on an undeniable high note, they’d still be fairly far away and still need to step over a fistful of opponents, but momentum makes a fan see all kinds of crazy things over the horizon. And fans want to see all kinds of crazy things over the horizon. We don’t need to patronize comedy clubs. Given the slightest opportunity, we’re delighted to kid ourselves.

No punchline remains to this would-be 2023 rush into the Wild Card scramble. Fifty years after we learned to never say never, it’s over before it’s over. Saturday’s loss in San Diego a person could perhaps slough off as a pause in escalating fortunes, adequate pitching being shaded by better pitching. Sunday, though, was a bow out of conceivable contention most apropos of these Mets. They didn’t pitch well. They barely hit at all. They were hit five times (a franchise mark for pitches leaving a mark). They incurred an injury that had nothing to do with hit-by-pitches. They looked defeated. They were defeated.

In a good year, limiting our advice to “Let’s Go Mets!” is sufficient. This isn’t a good year. Thus, at the risk of presumptuousness, I will take it upon myself to issue instructions to the players who have lost 48 of 90 and in whom I’ve expressed little faith regarding their next 72.

• Each Met who was dinged by Joe Musgrove and Tom Cosgrove on Sunday should apply additional ice to their bruises as applicable.

• Tommy Pham and his groin should take it particularly easy for four days, following imaging.

• Max Scherzer (5.1 IP, 5 ER) should put his uncooperative slider out of his mind much as Manny Machado put it out of Petco Park.

• Pete Alonso and replacement pick Kodai Senga should enjoy their All-Star jaunt to Seattle and not get hurt.

• Everybody from the hottest-hitting rookie catcher to the most interchangeable optionable reliever should take a breather over the break. Drape yourselves in comfy bathrobes and order in pancakes, or do whatever major leaguers who are not going anywhere after this actually do on their days off.

• Rest up for a few days and don’t dwell on a season that’s gone to hell and shows no sign of coming back.

Actually, that last bit applies to us. Mets fans deserve a break today. And tomorrow. And the next day. And the day after that. Come Friday, maybe we’ll be kidding ourselves anew that can’t we wait for our team to return. We’re hilarious that way.

by Jason Fry on 9 July 2023 11:59 am A little over a week ago, we were lamenting the fact that the Mets seemed incapable of winning any games; Saturday night found us grousing that they couldn’t, in fact, win them all.

That’s how quickly things change in baseball, and how speedily they’d changed for the Mets: Good starting pitching, timely hitting and actual luck — good luck, to be clear! — produced a six-game winning streak. The combination of the June From Hell and the Braves vanishing into the standings stratosphere meant our ambitions were only modestly recalibrated, but it at least was no longer complete madness to study the wild-card standings, size up all the (other?) flawed teams ahead of the Mets and wonder.

(A sidebar: Some number of seasons ago I was chatting with Greg and lamented that so many of our posts reacted instead of analyzing. Surely, I posited, our years of experience as Mets fans and our feel for the game meant we could stay more above the fray and remain cooler under fire, eyeballing possibilities and looking at the season more holistically instead of being at the mercy of all the reactive ebbs and flows of winning and losing. Greg listened patiently to all this and said something along the lines of, “we’re fans — we react.” I thought about how to refute that and stopped because I realized he was right. It was OK to leave cool analysis to a handful of wise, numerically more dextrous writers and just react.)

Anyhow, the Mets ran into a dominant Blake Snell, who had multiple pitches working with punishing effectiveness, and while David Peterson was pretty good overall, he had one blowup inning that left the Mets looking out at a crooked number in the Padres’ column. That wasn’t the entirety of the game: Snell’s tank suddenly dropped to E in the sixth and the Mets failed to cash in on numerous opportunities late, with only Francisco Alvarez denting the Padres as the winning streak ended. There were some dissonant notes beyond that: Francisco Lindor inexplicably forgot how to field and Starling Marte looked off-kilter in all aspects of the game. The former was probably a one-game WTF; the latter is unfortunately nothing new, as Marte’s 2023 has been one long nightmare.

(Second sidebar: It was pretty funny Friday night when Jeff McNeil, 2023’s other offensive black hole, drove in Marte for the go-ahead run. Marte was out there as the ghost runner because of his own conspicuous failure at the plate; if nothing else, I’ll give Rob Manfred and his fellow vandals credit for uncovering rich veins of baseball irony.)

Anyway, while Saturday’s loss did bear some hallmarks of the Mets’ spring funk, it mostly just felt like a loss instead of, say, prosecutorial evidence that you were a fool for giving this baseball team more precious hours from life’s all too limited stock. The Mets play their final pre-ASG game late this afternoon, and while a week ago I couldn’t wait for them to go away and preferably stay away, this morning I found myself thinking I’ll miss them. Things change quickly indeed.

by Greg Prince on 8 July 2023 12:24 pm It took ten innings, but the Mets made the Padres look like the Mets while preventing the Padres from making the Mets look like the Padres. This is to say the East Coast version of the Padres beat the West Coast version of the Mets, 7-5, in extras.

If I wasn’t following one of these teams closely, I’d have a hard time telling them apart, save for the one I don’t follow closely dressing for Cinco de Mayo on the Seventh of July. The San Diego Padres have a lot of highly reputationed players who, together, I assume would be unstoppable, but have instead been quite halting. I recognize that formula. It’s the one executed to a tee until very recently by the New York Mets. To those with no particular stake in the success of either ballclub, the Padres and Mets are two overpriced peas in an underachieving pod.