The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 16 June 2023 11:08 am In an unusually clever bit of scheduling, Major League Baseball has sent the St. Louis Cardinals to Queens this weekend to play the New York Mets, 40 years after a player the St. Louis Cardinals sent to Queens began to play for the New York Mets, albeit in Montreal. It was on June 15, 1983, that one of the top Cards in the entire St. Louis deck, Keith Hernandez, was traded to the Mets for Neil Allen and Rick Ownbey. The Mets were off on June 16, so Keith made his Met debut, versus the Expos, on June 17 at Olympic Stadium, going 2-for-4 in a 7-2 Met loss. Met losses were not uncommon in 1983.

After a while, though, they wouldn’t remain the rule.

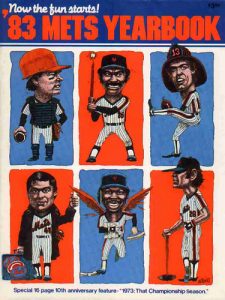

Not pictured: Keith Hernandez. Not started until late July: fun. On National League Town, the history-conscious podcast I do with my friend Jeff Hysen, we’re devoting a portion of the third episode of each month of the current campaign to a substantive segment on Met seasons and Met ballclubs that are reaching round-numbered anniversaries in 2023. It’s a feature we call IT HAPPENS IN THREES. This month’s three-sided salute is to 1983, and by way of wishing that deceptively successful last-place outfit a happy 40th anniversary, I thought I’d share a textual excerpt from the show, focusing specifically on the Sunday I’ve always considered the pivot point of not only that season, but the decade at large. For the generation of Mets fans who had muddled through the previous six years, the day in question — July 31, 1983 — was not only a blast in the moment, it lives on in memory as the beacon of light that directed us toward better times.

***The 1983 Mets upended their present in the Sunday Banner Day doubleheader that set off this stretch of crackling, competent baseball. Their opponents were the Pirates, in their last throes as a reliable NL East contender. The first inning of the first game was pure 1983 as we’d resigned ourselves to knowing it, with Walt Terrell giving up a single, a single, a walk and, with nowhere to put him, a grand slam to Jason Thompson. Frank Howard removed Terrell, brought in Scott Holman, and hoped for the best…not that the Mets nor their fans had any clue what that looked like. Holman held the Pirates at bay through the fifth, but Pittsburgh extended its lead to 6-1 by the sixth, and the banner parade was poised to be a march of forced frivolity.

Yet in the seventh inning, Mookie Wilson drove in a run, and in the eighth, Keith Hernandez and George Foster delivered back-to-back home runs, setting up a four-run inning that tied the game at six. Jesse Orosco, Neil Allen’s successor as closer and the Mets’ only All-Star earlier in the month, entered to start the ninth and kept pitching as if the banner-wavers weren’t getting antsy to display their works of art. Jesse pitched the ninth. And the tenth. And the eleventh. And the twelfth. And he gave up no runs. Neither did anybody on the Pirates until the bottom of the twelfth, which saw Darryl Strawberry single, second baseman Brian Giles single, utilityman Tucker Ashford walk, and SUPER utilityman Bob Bailor drive in Strawberry with the winning run. Remarkably, the Mets had won after trailing by four after four batters.

More remarkably? It wasn’t the best Met win of the doubleheader.

The Mets celebrated their opener, the fans marched jubilantly — the winning banner proclaimed the Mets “Take a Licking, Keep on Ticking” — and Game Two commenced with Mike Torrez on the mound. Perhaps as if to make up for the TEN walks he issued in Cincinnati a week-and-a-half before, Torrez threw ELEVEN shutout innings in the nightcap. That would indicate the Mets were in extras. Indeed, Torrez was matched inning for inning and zero for zero by Pirate starter Jose DeLeon, who was not only shutting out the Mets, he was no-hitting them. Not until Hubie Brooks singled with one out in the ninth had the Mets pierced the “H” column on the Shea scoreboard…though an instant later, Hernandez erased all that progress on a double play grounder.

Kent Tekulve took over for DeLeon in the tenth and the Mets continued to be stymied. After Torrez gave the last of his all — no Met starting pitcher would EVER again go eleven innings — Frank Howard turned to his Game One workhorse Orosco to keep Game Two going. Jesse shut down Pittsburgh in the top of the twelfth, setting the stage for the bottom of the twelfth, the signature half-inning of the season, and perhaps the overture for the era to come.

Facing Manny Sarmiento, Mookie Wilson singles. Hubie bunts Mookie to second. Chuck Tanner, manager of the Pirates, orders Sarmiento to intentionally walk Hernandez, setting up a double play possibility. It’s possible, but it’s also Mookie out there on second. Beware, Chuck Tanner! George Foster seems to cooperate, with a ground ball to second. Keith is forced, but the man we’ll soon be calling Mex slides hard into shortstop Dale Berra; Foster is running just as hard to first; and Mookie — with third base coach Bobby Valentine’s blessing — is flying toward home. Foster beats Berra’s Hernandez-compromised relay, while Mookie just keeps on comin’.

Wilson is a blur.

The 4-6-3 DP fails to materialize.

Mookie crosses the plate with the winning run in the SECOND twelve-inning win of the afternoon-turned-evening and present-turned-past. The Mets have done more than sweep the Pirates. They have, after being stuck in the same gloomy chapter of their lives since 1977, turned the page toward tomorrow.

The winning pitcher twice was Jesse Orosco, marking the first time a Met pitcher had won two games in one day since Willard Hunter in 1964. Jesse was so pumped that he declared in the postgame euphoria, “I’m ready to pitch a third.” Howard took him up on the offer as best he could. In the 14-game span that had just begun, Orosco would pitch nine times, every occasion a Met victory. Jesse earned five wins and four saves, propelling him toward a third-place finish in the NL Cy Young voting — pretty good for a relief pitcher from a last-place team.

The two weeks that were underway would be chock full of statistical and anecdotal delights. Mookie now had a signature play, and he trotted it out again, against Montreal, three days after the doubleheader. Same deal: Mookie scored from second on a potential double play grounder to win the game. Mookie on the run was already a familiar sight to Mets fans. The entire baseball-loving universe would see the difference Wilson’s wheels could make to a game’s outcome soon enough.

You can listen to the full 1983 segment and entire episode here or on your podcast platform of choice. You are also cordially invited catch up with National League Town’s previous IT HAPPENS IN THREES salutes to 1963 (from this April) and 1973 (from this May).

by Jason Fry on 15 June 2023 12:01 am Given a choice between a bedraggled, ill-mannered win and a jut-jawed, morally inviolate loss, you take the win every time. And the historical record will show that the Mets beat the Yankees Wednesday night, prevailing 4-3 in walkoff fashion in the 10th at Citi Field.

But if you were watching, you know that “win” is stretching it. It’s more like the Mets survived.

Survived, and didn’t exactly calm the troubled waters of their thoroughly roiled season.

The first half of this game was a relatively orderly affair and even a taut one, with former Astro teammates Justin Verlander and Gerrit Cole matching up in an old-fashioned pitchers’ duel that was notable for its contrasts. Cole looked like a classic power pitcher as he went through the Mets’ lineup like a combine, while Verlander inventoried his weapons, found his fastball a little lacking and so turned to the slider, using it and his other breaking pitches to confound the Yankees and condition them so that the fastball, reintroduced late in the proceedings, seemed a tick or two speedier than it was. It was a cerebral performance, one sorely needed, and the former Houstoners’ matchup ended after six with the teams tied at one run each.

And then the Mets commenced to play stupid.

Jeff Brigham walked Josh Donaldson to start the seventh and hit Anthony Rizzo, but then struck out DJ LeMahieu and coaxed a grounder from Isiah Kiner-Falefa, a baseball name I can’t decide whether to classify as wonderful or ridiculous. Rizzo was out at second, but Jeff McNeil made a throw he shouldn’t have made given Kiner-Falefa’s speed and Mark Vientos (who’d made some nice scoops earlier in the game) didn’t make a pickup he should have made, with the end result that a moment later the ball was caroming around on the wrong side of first and Donaldson was trotting home. Kiner-Falefa then stole second, moving to third when Francisco Alvarez threw the ball into center field, and then he stole home on not just Brooks Raley but apparently each and every person employed by the Mets. Seriously, it was like Daniel Murphy really had become invisible out there. At least Raley had the presence of mind to try and drill former Met Billy McKinney, which would have turned the theft into a dead ball, though that didn’t work either: Kiner-Falefa got up dirty and happy while McKinney looked like he wished someone had consulted him about the whole thing.

Down 3-1, the Mets tied the game back up in the eighth on a flurry of Yankee misdeeds: two singles, a walk, a HBP and another single — but Brandon Nimmo short-circuited the inning by inexplicably taking his eye off Vientos as his teammate was rounding third. When Nimmo realized Joey Cora had held Vientos he was basically at the shortstop’s usual address, and wound up making the third out trying to return to second. (Maybe he was safe, but if so no particular injustice was done.)

That was the second day in a row that the usually reliable Nimmo did something boneheaded, though he’s far from alone this year — Steve Gelbs, not exactly a bomb thrower in the criticism department, noted with apparent exasperation on Twitter that the 2022 Mets were known for crisp play and attention to detail, and so far the 2023 Mets are … not known for that.

Still, the game was once again tied and so on the two clubs played, with pretty much every Met fan waiting to see what would go wrong this time. Except that somehow didn’t happen. Adam Ottavino — one of so many Mets following up a terrific season with a thoroughly average one — allowed a leadoff double to Anthony Volpe in the eighth but stranded him, David Robertson worked around a LeMahieu double in the ninth, and Dominic Leone survived a 10th inning confrontation with Giancarlo Stanton. Which led to Nimmo facing Nick Ramirez with one out in the 10th and Eduardo Escobar as the ghost runner.

Nimmo, a man badly in need of redemption, smacked Ramirez’s second pitch off the right-field fence for a walkoff win, winding up crowned with popcorn and drenched in ice water at the center of a scrum of happy (or at least relieved) Mets. Given the outcome — hey, we walked off the Yankees! — I feel bad for noting that Escobar inexplicably stayed all but glued to second instead of going halfway while Nimmo’s drive was in the air, and might have been thrown out at the plate if a couple of Yankee defenders hadn’t made some flawed assumptions of their own.

Escobar wasn’t, though — he slid home safely and the Mets had won. Or at least survived. Close enough.

by Greg Prince on 14 June 2023 1:45 pm The starter can’t hold a four-run lead in the fourth inning.

Two relievers can’t maintain a tie in the sixth inning, and a third reliever is barred from the mound because of sticky hands in the seventh inning.

The center fielder can’t catch a ball lined essentially in front of his glove.

The five-hole hitter strikes out with two on and two out in the sixth, and three on and two out in the eighth, the latter directly after the cleanup hitter strikes out with three on and one out in the eighth.

The manager, whose team is down by one with two out in the ninth, resists the urge to use either of two power hitters to pinch-hit for a light-hitting backup middle infielder who has likely used up his quotient of base hits for the evening.

Can’t pitch.

Can’t catch.

Can’t make contact.

Can’t catch a break.

Can’t make their own breaks.

How’s that for a five-tool team?

Befitting a squad that finds multiple ways to lose, the Mets lost a one-run game to the Yankees at Citi Field on Tuesday night. Don’t be thrown off by the manufactured heat of the Subway Series or the reputation of the intracity rival. Everybody plays everybody, diminishing the impact of anybody playing anybody. Or as Abraham Simpson wrote so eloquently, “Dear Mr. President: There are too many states nowadays. Please eliminate three. I am not a crackpot.”

This loss from Tuesday could have happened against the Pirates or the Braves or the Blue Jays or the Cubs or the Rockies. We know that because in the past several weeks, losses like these have occurred to opponents like those, which is to say everybody who isn’t the Phillies. It doesn’t really matter who the Mets play. It doesn’t really matter what facet of the sport slinks into the spotlight as a result of the Mets not mastering it. Whatever it is a given baseball club has to do to win a given baseball game, doing it to winning effect is something New York’s National Leaguers cleverly avoid.

About the only thing the Mets are doing well these days is saying some version of, “My bad.” Max Scherzer, he whose sliders altogether ceased working in the fourth inning, told reporters, “You can put the camera right on me.” When the camera was put on Francisco Lindor, whose failure to put the ball in the play in the eighth with the bases loaded and less than two out signaled another opportunity was about to be lost, pledged, “I will be better.” Brandon Nimmo, who let a sinking liner baffle him until it fell under his grasp, admitted, “I just missed it.” The Mets are challenging for the league lead in accountability, if nothing else.

While Scherzer wasn’t getting nearly enough outs; Josh Walker (who put a runner on and wild-pitched him forward before Nimmo didn’t make his catch) and Jeff Brigham (who allowed Walker’s Nimmo-facilitated runner to score on a sac fly) weren’t shutting down a key scoring threat; Starling Marte was personally leaving seven runners on base; and Lindor wasn’t doing any better, there was the curious case of Drew Smith. Smith was curious as to why four umpires inspected his right hand and judged it too sticky to let him pitch the seventh, considering, he swore, it was no sticker than it was any other day when he’s been permitted to pitch. It was all sweat and rosin, he said. Scherzer said that, too, when the umps wouldn’t let him pitch in Los Angeles in April, but at least Max had actually pitched some in that game that day. Drew’s in the Tuesday night box score with zero batters faced. He’ll probably be suspended for ten games without the Mets because able to replace him because a) that’s the penalty, unless successfully appealed; and b) that’s the Mets in 2023.

The Mets’ manager in 2022, Buck Showalter, probably made in-game decisions that didn’t work numerous times, but they were easily overlooked because so much he did and his players did went right. In 2023, Showalter isn’t altogether fallible, even in losses. On Tuesday night, the same manager from 2022 made the right call bringing in Dominic Leone to bail out Scherzer, and he made the right call bringing in John Curtiss after Smith was turned around by the men in blue. The calls proved right, in any case, as neither of those down-the-depth chart relievers allowed any runs. Luis Guillorme starting at second can be said to have been the right call, too, in light of the Mets’ Luis singling in the tying run off the Yankees’ Luis (Severino) in the fifth. Our Luis is mostly up here for his defense. Actually, he’s up here because a roster spot opened after Pete Alonso’s bone was bruised. Guillorme hasn’t hit very much since the middle of last year, but his manager exhibited a little trust in an old hand, and Guillorme rewarded him by getting the Mets back even. You didn’t necessarily think getting back even would be on the Mets’ agenda once they jumped Severino for a 5-1 lead, but then along came Scherzer for the fourth, and 5-1 for the homestanders became 6-5 for the interlopers. Guillorme singling in Brett Baty from second made it 6-6. Nimmo not catching Anthony Volpe’s liner — not the easiest ball in the world, but far from Earth’s hardest — facilitated the Mets trailing again, 7-6.

Lindor and Marte’s back-to-back strikeouts versus Clay Holmes in the eighth, leaving the bases loaded as they did, tends to detract from one’s confidence in credentialed hitters. Still, if fatalism hadn’t overtaken your faith, you might have wanted somebody like lefty Daniel Vogelbach to take a crack at righty Michael King when Guillorme was due up as the Mets’ last hope in the ninth. Or, if you didn’t care about experience (or were worried about who was gonna play where in the hypothetical tenth inning of a game in which versatile Eduardo Escobar was burned as a pinch-runner for the unleaden if not unleaded Francisco Alvarez in the eighth), maybe you send up Mark Vientos and roll the dice that his bat has defrosted while he has sat. But Vientos hits about as much as he plays, and Vogelbach is emitting serious 1983 Dave Kingman vibes from the portion of the season when Keith Hernandez rendered his gloomy presence superfluous, except I don’t think we’ve lately traded for Keith Hernandez. When they put the camera right on Vogelbach, he’s in the dugout, and he’s in a warmup jacket that never has a reason to be removed. Daniel was last designated to hit in the middle of the Atlanta series, two series ago. One could ask what he’s doing on the Mets if he’s not asked to do the one thing he was brought to the Mets to do — go to town on righthanded pitching. Even if that town continues to be Doomsville (population Mets), it might be worth a trip to find out.

Or not. It could be I’m just groping for a fifth tool to tear into so my “five tools” construct will stand, however flimsily. I doubt I’m all that upset that neither of the V&V Boys batted for Guillorme. Still, I was pretty sure Guillorme didn’t have another big hit in him, and the moment did have that “do something!” urgency to it. Showalter didn’t do much to make the Mets’ own breaks in that spot, which doesn’t seem like the Buck for whose persona we (certainly I) swooned over last year. He also didn’t say much discernible when he was asked about it in the postgame presser. Perhaps his players and the scoreboard said all that needed to be said.

(Mike Puma has since reported Vogelbach is being granted something of a “mental break,” which might explain why he hasn’t been used at all for five consecutive games.)

Late in the SNY-produced Channel 11 telecast, a clip from The Matt Franco Game was shown. The clip, specifically, the one that explains why the game is universally recognized as The Matt Franco Game. It was from the Shea segment of the 1999 Subway Series, the Saturday game. The bases were loaded. Two were out. The Yankees led, 8-7. Franco was pinch-hitting for rookie Melvin Mora. Gary Cohen’s Hall of Fame play-by-play took it from there.

Now Rivera brings the hands together…runners take a lead at all three bases. One-two to Franco…LINE DRIVE base hit into right field! Henderson scores! Here comes Alfonzo…Here comes O’Neill’s throw to the plate…Alfonzo slides…he’s safe, the Mets win it! THE METS WIN IT! MATT FRANCO WITH A LINE DRIVE SINGLE TO RIGHT AND HE’S BEING MOBBED BY HIS TEAMMATES! Matt Franco, a two-run single off Mariano Rivera in the bottom of the ninth inning, and the Mets win it, nine to eight!

I don’t know how many weeks it required for me to get my full voice back after shouting and screaming and shrieking from almost the top of the Upper Deck at Shea Stadium when The Matt Franco Game went final. Beating the Yankees on July 10, 1999, especially by one run in the bottom of the ninth, was of paramount importance to this Mets fan as life stood that Saturday afternoon. To paraphrase Noah Syndergaard recently on wishing he could pitch he like used to, I would have given my hypothetical first-born to have beaten the Yankees that day.

Twenty-four years later, there was Guillorme, and there was King, and there was a one-run game in the balance, and Guillorme made the last out, my hypothetical offspring were in no danger of being bargained away. I wanted the Mets to win. I wanted the Yankees to lose. It wasn’t urgent urgent from where I sat, so who am I to knock Showalter for not desperately swapping out suboptimal options? Interleague overkill along with substantial personal mileage — fan passion that raged at 36 some nights merely simmers at 60 — can be pointed to for not life & deathing a 7-6 loss for the team I love most to the team I hate most. But mostly, it’s the team I love most not meriting very much voice-raising in 2023.

by Greg Prince on 12 June 2023 12:03 pm It’s a nice enough Sunday, the Mets game from Pittsburgh is on, I’m happy to be tuned in even if I’m only sort of paying attention to the Mets trailing the Pirates. I see Luis Guillorme called out on strikes because he was a second or so late in facing the pitcher with the count one-and-two, a ticky-tack rule rigorously enforced by umpires who don’t want their asses plopped into jackpots. That’s how baseball works in 2023. Get these games over with as soon as possible, every second counts. I’m thinking maybe Luis forgot about these MLB adjustments during his exile to Syracuse, or perhaps his ever-impressive beard inadvertently served as clock-blocker.

Next half-inning, still sort of paying attention, I hear Gary Cohen sum up the defensive changes Buck Showalter has made. Mark Canha is now playing first base, Jeff McNeil is in right field and Guillorme is at second. “Where was Guillorme playing before? Was he at short? At third?” None of that sounded correct. I consulted an in-progress box score. Francisco Lindor was the shortstop all day. He was the DH the day before, but he’s the shortstop every day. Brett Baty I was pretty sure was the third baseman. Yup, still was. Then I divined Guillorme had entered the game the previous half-inning as a pinch-hitter for Mark Vientos and his .167 batting average. You might want somebody to bat for young Mark if your confidence in the kid has sagged sufficiently. But Guillorme? Really? I foggily recalled from a few minutes earlier that the Pirates had made a pitching change, thus Buck must have responded in kind, Guillorme the lefty for Vientos the righty versus whoever the reliever was.

Guillorme as pinch-hitter? I mulled. He was asked to lead off the Mets’ most recent half-inning. In that situation, you just want somebody to find his way on base, so I guess it wasn’t altogether crazy to send up a guy who had hit so little before his mid-May demotion that his bat wasn’t once missed during his absence. It’s not like Luis, recalled on Friday, has never gotten on base. We know he can work counts by fouling off legendary quantities of pitches. He is, as Keith Hernandez likes to intone with assurance, “a veteran”. Luis generally knows what he’s doing. It just didn’t pan out, neither the plate appearance nor the knowing what he’s doing vis-à-vis the pitch clock. A year ago, Luis was a heady, clutch contributor and Buck’s calls were mostly golden.

Me, I was only sort of paying attention. I could complain about what the Mets seem incapable of doing these days, but I seem to have at least temporarily lost my ability to hang on every pitch. Perhaps I should try sweat and rosin to regain my grip. I knew the game was coasting along without much Met success. I knew McNeil had homered. I knew nobody else on our side had done anything remotely like that. I knew Carlos Carrasco didn’t last quite long enough. I knew Josh Walker had gotten out of Carrasco’s jam and further acquitted himself well in the next inning, and that Drew Smith stopped giving up home runs. I knew Andrew McCutchen had collected his 2,000th career hit, and that as long as it didn’t drive home any other Pirate or a lead to any other Pirate driving him home, good for him. I knew Mitch Keller had thrown a gem for however long he threw it, thanks to a) being conscious that Keller is having a heckuva year for the Buccos; and b) being hyperconscious that Keller was the guy who hit Starling Marte last September and effectively shortsheeted our offense for the duration of 2022. It took a second trip through the batting order for me to question if I’d seen Marte in the game. I was certain I would have noticed a Marte-Keller rematch. I checked that in-game box score to confirm…no, Starling had the day off. Like I said, I was sort of paying attention.

I knew we were losing, 2-1. I didn’t know we were going to lose, 2-1, but I rather suspected it, partly because of what I could glean from what I had managed to notice, partly from the tenor of the week-plus that had just passed. The Mets had lost seven in a row, then won one, now were trying to not lose anew. I had written up five of the seven losses. Maybe the cumulative losing had taken a toll on my attention by Sunday, despite the win on Saturday. I delved into Baseball-Reference and determined that since we began Faith and Fear in Flushing, the Mets have lost seven or more in a row seven times: once in 2011 (in April, undermining our confidence at the dawn of what became the Terry Collins Era); once in 2015 (more than a month prior to our salvation via Cespedes); once in 2017 (when things had grown so chippy around here that Jason and I turned off the comments section for the entirety of a road trip); twice in 2018 (an eight-gamer that ran through June 9 and a seven-game version that commenced June 19; fun times); once in 2019 (when I had the rare pleasure of recording for blog posterity each of the seven consecutive defeats); and the one we just endured in 2023. What all those dips into the abyss had in common is we treated them, after it became apparent the losing had reached streak proportions, as if they would never end and, after sucking up as much sucking as we could, acted as if we couldn’t bear to continue paying attention to the team doing the losing. Then a win would occur and attention would be paid, at first sort of, eventually at an extent approaching full engagement. That’s how a blog lasts nineteen seasons and counting. That’s how lifelong fandom earns its adjective.

The longest Met losing streak I ever experienced as a fan was in August of 1982: 15 games. It started while I was winding down the summer interregnum between my freshman and sophomore years of college. It continued during my rushed packing and thousand-odd mile drive south. It didn’t conclude until classes were in session. It was easier in 1982 to no more than sort of pay attention. By the time I was back in school, far from New York in the pre-Internet age, all I had was the next morning’s paper. They lost again. Damn. Oh well. If George Bamberger made a questionable move with a pinch-hitter, it happened without as much as peripheral awareness from me. The 1982 Mets finished in last place, 32 games under .500, 27 games out of first. I was as discouraged as I’d ever been since I’d begun watching, listening to, reading about and obsessing over the Mets in 1969, yet my attention rose to its standard status of full-mast when 1983 rolled around. I was barely older then than this blog is now and had never committed myself to write more than a composition or a book report about the Mets.

The new rules say a pitcher trying to pick a runner off base without himself courting an automatic balk can only disengage twice. I guess it doesn’t hurt for a fan to try it at least once in a while.

After the inning Canha moved to first, McNeil to right and Guillorme to second — none of which mattered, as Brooks Raley walked one and struck out three — Tommy Pham doubled with one out. He was the tying run on base, which was great. Pham doing something of an extra-base nature…I was wary. Pham seems to light it up most in Met losses. Coincidence, I’m sure, but you tend to infer what you begin to sense are trendlets. Another trip to Baseball-Reference is booked to ascertain if Pham the Met hits his best in games that become losses is something akin to a trend or just a figment of the selective imagination.

Pham HRs in Met wins: 2

Pham HRs in Met losses: 4

Pham RBIs in Met wins: 7

Pham RBIs in Met losses: 15

Pham total bases in Met wins: 21

Pham total bases in Met losses: 35

Absolutely coincidental. I’d rather have Tommy Pham getting big hits and take my chances that a teammate will follow in kind than subscribe to voodoo that suggests a Pham double represents a season ticket to Doomsville. Still, it’s kind of eerie. I guess I’ve been paying enough attention to notice Met quirks if not who among Mets is playing in a given inning.

Pham on second, one out, David Bednar pitching. The inning, by the way, is the ninth. It’s the Mets’ last chance. The game has coasted, but now it may be crashing. Gary is telling me how good a closer Bednar is. I actually knew that. I remember he was the Pirates’ lone All-Star last year, a solitary status well-deserved based on what I watched last September when I was paying close attention daily. I may have never seen a more fundamentally lacking ballcub than I did when the Pirates stumbled into Citi Field in 2022. They’ve certainly tightened up their act since then. They’re in first place in their division, and they’ve got a better record than we do, though the latter distinction hardly implies membership within an exclusive society. Bednar, who threw a lot of pitches to get some work in during Friday night’s blowout win for them, has Pham on second. He’s facing Baty, with Canha on deck. Either one would be the right person to knock Pham home. Baty’s run hot and cold, but can’t you picture his game-tying line drive and him landing on first base clapping hard and the Mets dugout going suitably nuts for his having rescued them from a series loss? I could. Alas, it was only in my mind. Baty flied out.

Then Canha, who would have made for a gratifying hero as well. Canha, who got off to a molasses start in this sped-up season, but has begun to produce. Canha, who we know can take it to one of the Pennsylvania teams from the way he beats Philly silly, so why not both (Canha’s BA versus PHI and PIT: .438; Canha’s BA versus all others: .227)? Canha, who had half of the Mets’ hits between the first inning and the eighth inning, a fact I half-recalled from the attention I had sort of paid this game. Canha, who suddenly plays first base much of the time because the Met who plays first base all of the time, Pete Alonso, is unavailable for the immediate future after he absorbed a pitch on the wrist in Atlanta. You just hope the effect of Alonso’s absence this year isn’t akin to the effect of Marte’s absence last year. Hope is one of those elements that is not rules- or health-dependent. You can have all you want, assuming you can generate it in the aftermath of a seven-game losing streak.

I had semi-sincere hope that Canha would come through and drive in Pham. As with Baty, I could picture it happening. A double in the gap, I decided. Pham scores easily. Canha shouting something triumphant while standing on second. Gary declaring that with the Mets down to their last out, it is Mark Canha, the key to their Keystone State fortunes, who keeps them alive, except Gary would declare it better than that because he’s a Hall of Fame broadcaster.

Usually I resist envisioning what’s going to happen because, unlike my hunch about Pham totaling most his bases in Met losses proving accurate, my percentage as prognosticator, particularly as it syncs to the Mets winning, is lower than Mark Vientos’s batting average. Clearing my mind of possibilities is the best way for me to proceed in the ninth inning. Maybe Canha would get that base hit. Maybe he wouldn’t.

He didn’t. The Mets lost, 2-1. They had three hits in total: Canha’s single in the second, McNeil’s homer in the fourth, Pham’s double in the ninth. It was still a nice Sunday. For me, not the Mets. We do lead separate lives sometimes. I left the game on until it became the postgame, I half-listened to Buck frame the Mets’ eighth defeat in their past nine games, though I must confess that I retained none of what he said five seconds after he said it, and then I told my wife, sure, put in the movie. Netflix’s DVD-rental service is going out of business, so we’re trying to watch as many unstreamable titles as we can before they shut it down in September. I’m also trying to watch as many Mets games as I can before the Mets shut it down in September — in case that’s their plan. I tend to make movie time wait on the Mets. I don’t know how long that plan will remain the rule.

Entering the series at PNC Park, I reasoned the Mets were a few games from a playoff spot with 99 games to play, and that’s the bottom line, no matter the sputtering that’s kept them from reaching the sunnier side of that bottom line. It’s three games later. They’re just as far off the pace, though with some extra teams crowding them out of more encouraging positioning. Ninety-six games remain. The Mets are still around. Maybe they’ll start playing better and move up. Maybe they won’t. I look forward to paying attention. Sort of.

by Jason Fry on 10 June 2023 9:33 pm On Saturday afternoon in Pittsburgh the Mets … won a baseball game.

That’s it. They played a baseball game and it ended with more runs for the Mets than their opponents, so they won. That shouldn’t be particularly noteworthy, yet alone breathtaking, yet after the frustrations of Toronto and the horrors of Atlanta and the hungover farce of opening night in Pittsburgh, it felt like quite something indeed.

I watched the game in a vaguely narcoleptic state after getting too much sun in a kayak on the East River, but I registered the details through my self-inflicted haze, from Kodai Senga‘s superb pitching (minus an inexplicable, Leiteresque few minutes where he forgot how to pitch) to Brandon Nimmo supplying excellent defense and the jarring sequence where the Mets’ infield did not, though in fairness the first of their two errors in that frame should have been on the second-base umpire, who misread Luis Guillorme‘s superlatively fast transfer at the front end of an attempted double play as a drop. This time the roof didn’t cave in: The Mets tightened up and got out of the inning with just a single run scoring, leaving the game tied. Which it stayed until the seventh, when the Pirates chose to walk Guillorme so slider specialist Dauri Moreta could go after Mark Canha. I’m easily one of the planet’s Top 100 Guillorme fans, but that didn’t make a whole lot of sense to me; Canha suffered the indignity of a 2-1 slider outside being called a strike but then got one from Moreta without enough break and lashed it up the gap for a double, followed by about 75,000 exhales in the Greater New York area.

The Mets kept going, adding two more runs on a Francisco Alvarez home run and another Canha RBI double, and their relief corps choked out the Pirates without undue trouble, leading to what in happier times might be called a rather ho-hum 5-1 win. This was the kind of game ideal for a baseball nap that erases the middle innings, a mildly pleasant diversion fated not to be thought of again once 28 hours had passed. Which was what the Mets as frustrated players and we as enraged fans sorely needed, what with the humdingers and barnburners all going in the enemy column of late.

It was just a baseball game. The Mets won it. It’s a formula they’re encouraged to repeat.

* * *

In case you didn’t see it, Joel Sherman of the Post got Steve Cohen on the horn to basically ask why he hadn’t unleashed a red wedding on his employees given a frustrating season and its recent nadir.* Cohen’s lengthy ruminations on the subject of how to react when everything goes awry isn’t satisfying if you’re looking for catharsis, but it’s undoubtedly a lot more healthy than what any of us would have done if unwisely empowered to take action after the 13-10 curb-stomping by the Braves or whatever the hell that was Friday night in Pittsburgh. It’s worth reading and thinking about. In case you didn’t see it, Joel Sherman of the Post got Steve Cohen on the horn to basically ask why he hadn’t unleashed a red wedding on his employees given a frustrating season and its recent nadir.* Cohen’s lengthy ruminations on the subject of how to react when everything goes awry isn’t satisfying if you’re looking for catharsis, but it’s undoubtedly a lot more healthy than what any of us would have done if unwisely empowered to take action after the 13-10 curb-stomping by the Braves or whatever the hell that was Friday night in Pittsburgh. It’s worth reading and thinking about.

* * *

Back in 2001, Topps celebrated its 50th anniversary of making baseball cards by unveiling a set called Topps Heritage. It presented 2001’s players on cards based on the 1952 design; Topps has advanced year by year since then, chronologically revisiting each of its original designs for a new crop of players. One’s fondness for Topps Heritage depends on how one views the original design being resurrected: I loved 2013 Heritage because I think 1964 Topps is the pinnacle of its designs and was left cold by 2017 Heritage because I think the 1968 Topps “burlap sack” design is a low point; reasonable people might have the exact opposite point of view.

Topps generally plays things straight with Heritage, but every so often they’ve paid sneaky homage to some aspect of the set that came 50 years before. From a Met fan perspective, the pinnacle of such efforts was 2011 Heritage, which left Met fans complaining that the Mets hadn’t received a team card and a lot of the players were shown hatless in generic-looking uniforms. It fell to baseball-card dorks like me to explain what was going on: Back in 1962 Topps had shown nearly all of the brand-new Mets the same way (a format known in the trade as BHNH, or Big Head No Hat) and skipped a team card; since 2011 Heritage used the ’62 design, Topps was being true to its antecedents. They even went so far as to create a David Wright “error” card listing him with the Reds, in tribute to fellow third baseman Don Zimmer‘s ’62 card that shows him as a Red wearing a Mets hat.

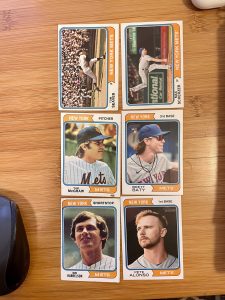

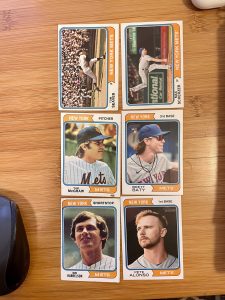

This year’s Heritage set uses the 1974 design, which isn’t particularly a favorite of mine, and I paid the Mets selected no particular heed while obtaining a set. But then I read a fun post noting that cards in the set that echoed those produced the first time around, and got to digging. Sure enough, Topps is up to something with this year’s Mets: Pictured are the ’74 Topps cards for Tom Seaver, Tug McGraw and Bud Harrelson, and the ’23 Heritage cards for Max Scherzer, Brett Baty and Pete Alonso.

Coincidence? Nah — the card numbers even match. Well played, Topps!

* because that was totally the nadir, right?

by Jason Fry on 9 June 2023 11:14 pm

by Greg Prince on 9 June 2023 11:48 am The schedule works out well for the Mets this weekend, positioning them to take advantage of their place in the standings. They are three games out of the third Wild Card spot in the National League and they are in Pittsburgh for three games this weekend to take on the team that it turns out is their target. The Pirates, if you haven’t noticed, are the NL’s six-seed du jour, themselves running two games behind the provisional five-seed Marlins. The situation is fluid, but if the playoffs started today (which they don’t), the Pirates would be in. If the playoffs started today, the Mets would be out.

Way out.

If it seems irrelevant to the point of laughable to invoke playoffs after what we’ve witnessed from the Mets these past three days in particular and seven weeks in general — they’ve been more Jim Mora than Melvin Mora — well, it’s June 9 and 99 games remain in the 2023 season, and if you renew your Mets fandom annually for the long haul of a given baseball season, that’s what they’re giving us. We have a chance to remain invested in the pursuit of a postseason berth. Just not the one we thought would be in our grasp.

The Mets’ participation in the divisional race is essentially over. It’s June 9, and 99 games remain in the 2023 season, yet the Mets have consigned themselves to a different, lesser competitive sphere for the foreseeable future. Granted, in these Air Quality Alert times we can barely foresee down the block, but these Mets have to look up too high to make out their initial goal of first place in the NL East. On a clear day, from where they have mired themselves in fourth, they can no longer see Atlanta.

Thursday night’s finale in their three-game series versus the Braves at Truist Park hinted at what could make the Mets viable for the rest of the year and emphasized all that may very well eliminate them from even semi-serious consolation contention. They did forge a comeback. They did add on. They did exude enthusiasm and, for a while, didn’t say die. They played young and spunky and gave us hope at a hostile locale where fatalism had overtaken our view of what was possible.

Ultimately, though, their fate was to lose, 13-10, in ten innings to the Braves. If this type of loss had come at the hands of any other National League opponent, you’d almost shrug it off as one of those games where each club went to town on the other club’s pitching and the slugfest simply didn’t end the right way. But, no, this wasn’t that. This was horrible Met starting pitching from a source whose excellence was advertised as implicit; horrible Met relieving from everybody asked to get enough outs to help us make it through the night; and, despite the ten runs and fourteen hits and the overcoming of an early 0-3 deficit, horrible offense when it mattered most.

The team that can produce a grand slam — Brandon Nimmo’s — to compensate for their co-ace’s — Justin Verlander’s — staggering shortfall, and slot their hottest shot rookie catcher ever — Francisco Alvarez — as DH and get two home runs from him, and survive, to a point, a night without their biggest bopper (get well, Pete Alonso’s wrist), isn’t without merit. Two hits apiece from McNeil, Lindor and Baty. Three from the slowly awakening Marte. Tommy Pham continuing to make himself something more than useful. No sign of Daniel Vogelbach anywhere except in the dugout where he patted backs and shouted encouragement. Through the tops of five innings, the second through the sixth, mainly at the expense of otherwise able Atlanta starter Spencer Strider, we saw what this team can do and why we expected so much.

In the bottoms of innings, and as the night went on, we grew to understand why we now say adios to expectations. Verlander had no command and no answers. The most-accomplished pitcher working in the major leagues lasted three innings, allowing seven hits and four walks, somehow not trailing when he left. After Justin, it was bullpen roulette straight out of the Jerry Manuel era. Whoever Buck Showalter called on imploded to some degree. The nth degree came down to Tommy Hunter, the quintessential “I forgot he was still here” reliever, who was all Buck had available to stem the recurring Brave tide in the bottom of the tenth. Atlanta, like New York, was furnished with a complementary baserunner on second. Unlike when New York had theirs in the top of the tenth, the Braves pushed — powered — theirs across. Five different Brave batters homered, off five different Met pitchers. Seven Mets pitched. Each was scored upon either organically or via inherited runner.

In the realm of the now dormant Met-Brave rivalry (because rivalry implies two comparable foes competing at the same level for the same prize), the most disturbing part of Thursday night was the inevitability of it all. Tuesday night, the Mets held a 4-1 lead and lost to the Braves. Wednesday night, the Mets held a 4-1 lead and lost to the Braves. In 2022, the Mets held a double-digit lead at the outset of June and lost the NL East to the Braves, with Games 157, 158 and 159 in Atlanta serving as death blows. Thus, despite the energizing nature of Nimmo slamming grand and Alvarez’s bombs bursting in air and the 10-6 lead the Mets held as late as the middle of the sixth inning on Thursday, you kind of knew what was coming. Or who was coming.

Against the Braves, the Mets find a way to score ten runs through six innings, yet then go silent for as many innings remain. Against the Mets, there’s always a Brave ready to go as deep as a Brave needs to go to do the Mets in. Austin Riley off of Verlander. Marcell Ozuna off of Stephen Nogosek. Travis d’Arnaud off of Drew Smith. Orlando Arcia in the bottom of the ninth off of David Robertson. Finally, Ozzie Albies off of Hunter to walk/stomp it off in the tenth. Tommy took the loss. David was charged with a blown save. None of the above, nor non-gophered relievers Jeff Brigham and Brooks Raley, prevented runs. Team effort that.

The blur of the season that’s been in progress for more than two months yet feels endless has landed at a record of 30-33. If it looks familiar, that’s because twenty games ago, the Mets’ record was 20-23. Experientially, there’s no frigging way the Mets have played .500 ball for the past three or so weeks, yet this stretch has included that five-game flourish of fantastic finishes versus Tampa Bay and Cleveland and that three-game sweep of Philadelphia. Hard to remember, I know. During both of those oases in this otherwise arid campaign, I figured, all right, we’re back on track to where we’re supposed to be going, let’s go. Except this same stretch has also included two losses in three games to the Cubs; two losses in three games to the Rockies; three losses in three games to the Blue Jays; and three losses in three games to the Braves, each component of that last trilogy of horror lost despite having led in all of them by three or more runs, representing a new milestone in Met consecutive-loss futility. Also, if you’re keeping masochistic score, the Mets had never lost a 13-10 game before. Until now.

These Mets are lucky to have gone 10-10 in these last twenty games.

These Mets are lucky to be only three games under .500.

These Mets may appear to be a bunch of stiffs, but they are lucky stiffs.

These same Mets could sweep the surprising Pirates this weekend and, if other games in other places cooperate, they can substantially improve their playoff position by Monday (when, like today, the season doesn’t end), yet I doubt, even if they pulled this temporary 180, I would believe the Mets are heading toward the top tier of their division or their league. Maybe that’s where they were “supposed” to be, but the supposition has proven inaccurate. This is a ballclub that can do some fine things, but isn’t doing them on any kind of sustained basis. Maybe they still will, because it’s a long season, and long seasons can be forgiving if the causation of early or not-so-early missteps can be addressed and reversed. Maybe it will be enough to keep them engaged in a chase for something other than their own tails, because six teams now make the postseason in each league, and such a format forestalls funeral arrangements for a ballclub one good weekend away from fortifying its fortunes. Not dead yet is what the Mets have going for them with 99 games to play.

At the moment, the Mets are in the fourth place in the race for the third Wild Card in the National League, three games behind Pittsburgh, with both San Francisco and Philadelphia between them. San Diego and Cincinnati are closer to rear of the Mets than the Mets are to the rear of the Pirates. It’s all volatile and subject to change, but get to know these names, because these are now our neighbors. The Wild Card race, if the Mets manage to remain as lucky as they’ve been of late, is where we live.

They trail the first-place Braves by 8½ in the NL East, but I don’t expect to pay much attention to that team or that margin very much for the rest of this season. The Braves are out of the Mets’ league.

by Greg Prince on 8 June 2023 9:33 am Tough walking around New York with all that smoke wafting down from Canadian wildfires. To take our minds off the ominous skies, let’s enjoy some Mets highlights from Wednesday night in Atlanta!

All of New York can see how great its Mets are doing. No delay — the game starts on time!

A first-inning run — and none allowed!

The rookie catcher starts — and belts a home run!

A two-run lead!

The emergency pinch-runner stays in — and whacks a two-run homer!

A three-run lead!

The starting pitcher strikes out ten!

The starting pitcher walks nobody!

The first reliever out of the bullpen strands his inherited runner!

The bases loaded in the top of the seventh…a wallop to deepest right field — RBI!

Two relievers in the bottom of the seventh — a perfect inning!

FIVE RUNS SCORED — the most since the trip to Colorado!

An important x-ray announced as negative!

That’s gotta be the only element of this ballgame you could call negative — right? I mean, what a bunch of great things in the Mets game versus the Braves! And a hundred more games of Mets baseball potentially just like it remain!

The final score from Wednesday night? Air quality being what it is, I can’t make it out through Mets-colored glasses. What with all those overwhelming positive developments, though, I’ll just assume everything worked out fine.

On National League Town this week, we empty out our 2023 Mets Hall of Fame notebook and fill the 2024 ceremonies with a quartet of nominees. Listen here!

by Jason Fry on 7 June 2023 1:02 am White Flight Stadium has been a house of horrors for the Mets for some time now, but the home of the Braves outdid itself Tuesday night, first with a rain delay that didn’t actually feature rain — they watered the goddamn infield when guys could have been playing on it — and then with horrible things happening to the Mets, who lost 6-4 in a game that felt more like 60-4 when it was mercifully over.

What went wrong? What didn’t go wrong? Carlos Carrasco pitched well until he didn’t, coming apart in the sixth inning before Drew Smith let the already damaged roof cave in. The Mets had a brief uprising in the fourth with two two-run homers but you could already hear the minor-key chords warning that you were being set up. Those homers were half the hits the Mets collected all night, with no tallies whatsoever after the fourth. The fielding was atrocious, with Jeff McNeil‘s agonies in left sitting front and center but a number of other plays not made. And OK, to be fair, the Braves are pretty goddamn good and came through when they needed to.

However you apportion blame, the Mets are 30-31, and two more nights in Atlanta seem an unlikely recipe for curing whatever’s ailing them. Particularly when what’s ailing them seems to be everything. A budget that would be envy of some nation states has created a tissue-paper juggernaut that’s under .500. The Mets look poorly assembled, a spasmodic Frankenstein machine that’s constantly shedding pieces, leaking oil and freezing up when it isn’t blasting away at its own feet. Yes, there are 101 games left to go, but that’s starting to feel more like a threat than a promise. The Mets should revert to the mean and play to the backs of their own baseball cards, but 61 games are gone and they haven’t done so yet.

Sometimes should turns into should have and is quietly shelved with the other resentments and disappointments. Eventually the guy sitting placidly and waiting for the luck to turn stops looking like a patient sage and starts looking like a sucker. Funny how he’s always the last to know.

* * *

It’s the Texas Rangers’ problem and not ours any more, but Jacob deGrom will have a second surgery on the UCL in his pitching arm, taking him out of action until late 2024 at the earliest … and who knows what he will be when he does return.

Again, not the Mets’ problem — it’s the Rangers’ issue for the next 4+ years and $185 million. But it’s terrible loss for all of us who have fond memories of deGrom, which is to say all of us, just as it’s a terrible loss for baseball, which is so much better with an electric deGrom taking the ball every fifth day. DeGrom at his best did something incredibly hard and made it look not just effortless but like art, and if you were watching on those days you knew how lucky you were, you sensed that were watching something indelible that you’d remember for as long as you’re a baseball fan.

That deGrom went from serially incredible to seriously unreliable isn’t a failing of his, or the Mets, or the Rangers, or anybody else. Rather, it’s a reminder of how hard pitching is and of the toll it takes, and how quickly it can all go awry. A top-flight pitcher at the top of his game is a thing to cherish, because pitchers break. Each and every perfectly executed pitch — a 98 MPH fastball dotting the corner, a 12-6 curve buckling a hitter’s knees, a slider veering away from a bat like magic — bears its own shadow, carrying the possibility that it could be the last one.

by Greg Prince on 5 June 2023 4:57 pm As noted often in this space, I consider listening to Gary Cohen talking Mets baseball a perk of being a Mets fan. Listening to him on Saturday, both while sitting in the Shannon Forde Press Conference Room as he and his fellow inductees prepared for their big moment on the field, and then from the press box while he stood before the fans who gave him and Howie Rose the applause that have been building up for more than three decades apiece, represented a feast for my auditory senses. Little that Gary says goes in one ear and out the other. It zips its way to the brain, settles there, and gives me more than I counted on thinking about.

Two observations of Gary’s from Saturday stand out for me here on Monday.

1) In response to my fancy reportorial question — posed to the table full of Famers, answered by the announcers — about what really surprises a fully grown youngster who dreamed of making it to the big leagues and then actually did, whether via pitching or hitting or talking, Gary (after Howie spoke thoughtfully and knowingly about the rigors of travel) offered a layer of perspective he admitted to not having while spending all those days and nights in the Upper Deck.

“Going from being a fan to a broadcaster at the highest level in Major League Baseball, I think the thing that you learn very quickly is what extraordinary athletes these guys are. You know, it’s very easy for people to sit in the stands and watch major league baseball players fail, and it’s a game of failure, but even the last guy on a major league roster is an extraordinarily talented athlete, and just standing behind a batting cage and watching the hand-eye coordination involved, again with the lowliest of major leaguers, is so far beyond the ken of those of us who can’t do those things, I think it makes you appreciate just what this game is, and how difficult it is to play, and how monumentally talented all of these players are. To me, that was the most eye-opening piece.”

2) During the speech itself, Gary wished to single out as best he could “so many people who have helped me on my way to this moment,” starting out where one might expect a person might on a day such as this:

“My mom, who passed away earlier this year. She was a Giants fan until the day Willie Mays became a Met. Then she became a Mets fan.”

It’s worth noting that by the time Mrs. Cohen switched allegiances, her son was already ensconced upstairs at Shea. His idol down below was Bud Harrelson. His idol on his transistor radio was Bob Murphy. We know whose path Gary Cohen followed to the big leagues. The rest of us don’t carve out any kind of road to the big leagues beyond going to games or following them over whichever devices are most contemporary. We’re just thrilled to be along for the ride from however far we attempt to breathe it in.

I’m thinking of all this following the weekend when Gary and Howie, in the company of Al Leiter and Howard Johnson, received their due in the Hall of Fame, because of the way baseball goes on. Baseball went on Sunday, the day after those exquisite ceremonies. The Mets played the Blue Jays again, and lost to the Blue Jays again. A fan would have to exercise Cohenesque restraint to not say out loud that the result sucked. But it did. It doesn’t mean the players who came out on the short end three days in a row sucked. They are indeed extraordinary athletes, right down to the last guy on the roster. But sometimes the combined product of the collective efforts of the extraordinary athletes in whom you threw in your lot for life before you turned ten kind of sucks. The Mets lost on consecutive days by scores of 3-0, 2-1 and 6-4. Something wasn’t functioning as well as it could have.

On Sunday, it was the starting pitching, which had been outstanding at Citi Field all week, and sublime all season when it fell to Kodai Senga at home. The secret ingredient to Senga’s Citi success was he was him being the most well-rested cuss in Flushing since whichever mystery member of the maintenance staff who was called on to mop up that perennial puddle in Promenade behind home plate chose to maintain instead his nap. I’m referring to the puddle that I swear just sat there unattended for the bulk of the 2010s, and I’ll have to check on it next time I’m in the neighborhood of Section 514. Kodai, who’s absorbed opponents’ swings and misses regularly during Citi starts, didn’t pitch on four days’ rest in Japan, so the Mets didn’t push him. Yet he was so good starting out this homestand against the Phillies, and the pieces don’t really exist for a six-man rotation that would keep him on extended rest into perpetuity. Thus, Buck pushed him. The lack of rest pushed back. Senga didn’t make it out of the third. The bullpen got leaned on. Much of the relief corps withstood the pressure of having to go a six-and-a-third. Dominic Leone, who gave up the deciding two-run homer to Brandon Belt in the seventh, didn’t.

It was also the sporadic offense not helping matters on Sunday. Huzzahs for four home runs hit by Mets. Raspberries for nobody being on base for any of them, nor any other episode of scoring by any Met that didn’t involve a solo home run. Do you know what always happens when the Mets hit four solo home runs and that accounts for the totality of their scoring? They lose. That’s not an exaggeration. The Mets have launched four solo home runs five times in their history without figuring any other way to put up a run, and every time they have lost. Solo home runs can be very handy. They can also be fool’s gold if you think they’re all you need to thrive.

Still, good for Tommy Pham going deep twice at Citi Field, the first two times he’s done it at home as a Met (it would have been sweet to have followed up the Hall of Fame with the Haul of Pham). Good for Starling Marte flexing his muscles once again. And really good for Pete Alonso taking over the all-time lead from Lucas Duda for most regular-season home runs hit by a Met in the ballpark that’s been open since 2009 and that by 2010 still seemed like Death Valley — or at least Locust Valley — when it came to slugging. Fences have come in a few times since we bemoaned how hard it was for anybody to hit a ball out of Citi Field. It got easier if not easy. On Sunday, Pete needed a replay review that shrugged when asked about orange lines and black backdrops. I didn’t think Pete’s 72nd lifetime Citi dinger left the yard once I watched it bouncing up and not quite over the wall in left a few slow-motion times. But the Blue Jays didn’t ask me to do the reviewing. Pete’s reaction to setting the record was that it was “sick,” which even Kodai Senga doesn’t need a translator to know means swell.

Pete’s bounce above the orange line, wherever it did or didn’t tick, might have been the only bounce or bouncelike element that went the Mets’ way on Sunday. Pham wasn’t as much of a fielder as he was a slugger, not swiftly scooping up an errant Francisco Alvarez throw on a stolen base attempt that instantly became a run. Alvarez might have tagged the runner, Matt Chapman, a nanosecond before any of his toes touched the plate, but the angle that would have proved it conclusively didn’t prove anything. Besides, Chapman felt safe, and go challenge that. Marte also hit a triple that turned into a ground-rule double early on, auguring One of Those Days when the Mets really could have used the different kind.

Again, though, they’re all talented and capable, which makes it that much more aggravating when the talent and capability checks in at .500 after 60 games, just as it checked in at .500 after 54 games…and 50 games…and 46 games…and 34 games…and 32 games…and it’s been One of Those Seasons, hasn’t it?

Yet there have been so many seasons when we, the fans in the stands or on the couches in front of the TV or in the car with the radio tuned to 880, know a stop & start .500 season with talented players and a forgiving playoff qualification format beats the lesser alternative. The lesser alternative, whether we experienced it directly or feel it pulsate within our DNA, could be found in 1962 and 1963 and 1967 and 1978 and 2017, five losing years picked not at random. In a particular order…

2017: It’s the year after a Wild Card season when the Mets have opted to go in a different direction: down. Let’s hope 2023 doesn’t ultimately resemble that year (70-92) too closely. Still, 2017 did introduce us to a recurring supporting character in our ongoing story, a catcher from Puerto Rico named Tomás Nido, a catcher whose first name I always stop to make sure I accent properly when it comes to his “á”. It doesn’t look like that will be a continuing concern for this correspondent, as Nido has been designated for assignment to clear space for the return of Omar Narvaez from the injured list. Narvaez the veteran, Alvarez the phenom; no room at the two-catcher inn any longer for the second-longest tenured Met who never grew into a consistent hitter at the major league level, but, as Gary Cohen reminded us, that doesn’t mean he wasn’t any good. He had a few big hits across his seven mostly partial season in the bigs, and his catching was big league-caliber. Tomás was kind of a throwback — the career backup receiver who could be depended on in a pinch by one organization for a very long time. It’s not what a kid dreams of growing up to be, but sometimes you get that far, you get a little farther. By the end of 2022, Nido was the starting catcher for a playoff team in a pinch. Should we cross paths with him in another uniform, I will be sincere in referring to him as an Old Friend™.

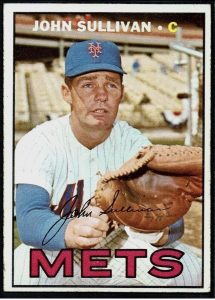

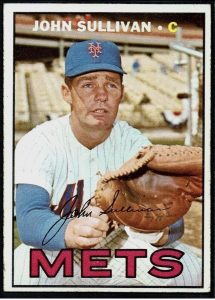

1967: It’s the year every Mets fan should recognize as the season that launched George Thomas Seaver on his way to every Hall of Fame in sight: the one in Flushing, the one in Cooperstown, the one in Cincinnati, even (sigh). Seaver probably launched himself, but, as those who joined him in official Met immortality Saturday emphasized, nobody gets where he’s going by himself. Tom himself made a point of mentioning the most distinguished catchers with whom he’d worked when he accepted his plaque Upstate in 1992: Jerry Grote, Johnny Bench, Carlton Fisk. Also catching Seaver’s sensational pitches when Tom was 22, besides young Grote, was a journeyman named John Sullivan. John’s journey, which ended in the broadest sense when he died at age 82 last week, wound through the 1966 Rule 5 draft from which the Mets selected him and thus had to keep him around all of ’67. Sullivan gave the Mets 65 games of catching, including seven in service to the rookie righty from Fresno. With Sullivan catching, Seaver posted an ERA of 2.55, the lowest Tom registered in tandem with any catcher in his freshman campaign. The very first time Tom totaled double-digit strikeouts (12), it was Sullivan behind the plate framing and cradling every last one of them. John spent only a year in what we’ll call the Nido role in New York. He’d work as the bullpen coach for the Blue Jays long before we had to worry about them on the Mets’ schedule, through the ’80s and into the ’90s, and enjoy a Hall of Fame-worthy moment himself. When Joe Carter hit the home run that won the 1993 World Series for the Jays, it was Sullivan who retrieved the historic horsehide and, though officials from Cooperstown came looking for it, held onto it long enough to hand it to Carter. “Touch ’em all, Joe,” John was essentially saying to Joe about all 108 stitches on that baseball. Few of us will ever be part of a bigger moment.

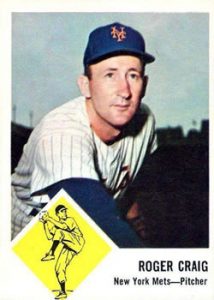

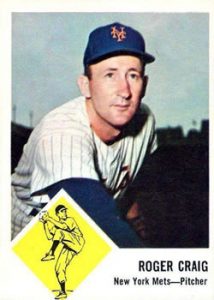

1962 and 1963: These years speak for themselves. Rather, the announcers who set the precedent for Gary and Howie, spoke to us about them in case we missed them. Lindsey Nelson, Bob Murphy and Ralph Kiner filled us slightly younger kids in on the wonders of the Polo Grounds seasons, the legend of Casey Stengel and the players who would be mythical figures if they weren’t real. Thanks to their storytelling, I learned who Roger Craig was. I learned Roger Craig, righthander from North Carolina, was a seminal figure. I learned Roger Craig was the Mets’ very first starting pitcher. I learned Roger Craig pitched without much run support. I learned that yes, Roger Craig lost a lot of ballgames, but it was also drummed into me at an early age that to lose 20+ games in a single season (Craig lost 24 during the first Met year and 22 the second), you have to be pretty good to get the ball and keep going out there and giving it another try. Roger Craig, who died this weekend at 93, helped the Dodgers in Brooklyn and Los Angeles to world championships before there were Mets; as with securing the services of Gil Hodges, Don Zimmer, Clem Labine and Charlie Neal, the new club in New York saw Craig’s presence in Manhattan as a potential lure to Bum-bereft Brooklynites unsure about crossing certain geographic and psychic bridges into the land of Metsdom. Roger also helped the Cardinals to a world championship once the Mets had mercy on his competitive soul and traded him to a contender. He threw more than 230 innings in consecutive seasons as a Met, all while bearing the brunt of just about everything going wrong. Photos from that period suggested a gentleman trying hard not to appear beleaguered. Interviews conducted by Kiner of Craig conveyed a person who’d survived the ordeal of 40-120 and 51-111 just fine. Roger made himself and his recollections available to Ralph plenty during his years as a coach and a manager at various National League stops, right up to his leading the Giants to the World Series in 1989. Our first pitcher visited Citi Field in 2012 on the exact fiftieth anniversary of our first game: April 11 (welcomed home despite teaching Mike Scott the split-finger fastball). On that date in 1962, Roger and the Mets lost, 11-4. On that date in 2012, with Roger Craig tossing out the ceremonial first pitch, Johan Santana and the Mets lost, 4-0. You wouldn’t accuse either of those men of not being a pretty good pitcher.

Roger, an Original Met if ever there’s been one, was the longest-living Met when he passed away. The oldest among our guys now? Gary Cohen’s mom’s favorite player, the Say Hey Kid. Willie Mays, at 92, tops the list, as he tops so many of them.

Thanks, Jim. 1978: Mike Bruhert, I’m pleased to announce, is still alive. I’d be even more pleased to announce that I ran into him on the LIRR platform at Jamaica Saturday night after Hall of Fame Day at Citi Field. There was a delay born of a signal problem, and there was a lot of standing around, and then, as if from the cornfield, appeared a man wearing a BRUHERT 26 Mets jersey, honoring one of the Mets’ most electrifying starters — actually from Queens! — from the only electrifying portion of the 1978 season, the first part, when the Mets briefly topped the NL East standings and stayed close to .500 until Memorial Day. I don’t have to look any of that up. I’ve reveled in that too-brief spurt of success for 45 years now. I was 15 then. It made an impression. Bruhert in the rotation and Mardie Cornejo in the bullpen were the big surprises in the big push to respectability following the misery of Seaver’s exit and the rest of 1977. The entire enterprise faded (last place awaited in ’78, just like it had in ’77, just as it would in ’79), but for a few weeks there, it was very exciting and very gratifying and if I had bumped into somebody wearing a BRUHERT 26 jersey then, I would have plotzed. Running into somebody wearing one on Saturday had almost the same effect on me. Never mind that I had just finished being a media representative Saturday afternoon, asking professional-sounding questions at a press conference, and casually ambling along the field before the Hall of Fame ceremonies, and taking notes in the press box without uttering a yea or nay. By Saturday night, I was just me again, a fan who saw BRUHERT 26 and had to ask, after ten minutes of railroad delay made all of us static and therefore readily accessible, “excuse me are you…?”

He wasn’t. Not quite. It was Mike Bruhert’s brother, Jim. It was all I could do to not respond, “OHMIGOD, YOU KNOW MIKE BRUHERT!” I mean, Mike Bruhert’s brother, Jim, is a person in his own right. I should have been delighted to meet him and left it at that. Yet he was honoring his brother, and how do you not follow up on a jersey you simply don’t see every day? Jim was kind enough to tell me he had the jersey made up in 2008, which explains why it carries a drop shadow and a FINAL SEASON patch. Jim, who had just gone to the game with his family, patiently explained between my babbles and burbles that I was the second person to ask him if he was Mike Bruhert. “Only the second?” I thought.

I’m not looking up Mike Bruhert’s career numbers. I don’t have to. He was a Met when I was a kid, which means he remains larger than life; larger than a delay at Jamaica, as aggravating as that can be. Like Gary Cohen said, all these guys are monumentally talented, though when I was 15, I’d like to believe I understood that already.

|

|