The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 24 May 2023 2:34 pm The 2023 Mets were expected to do big things. For the first 43 games of this season, they resisted those expectations. Then came last week: Games 44 through 48, each won by one run, each won after at some point trailing; each won as affirmation that the expectations were merited; each furnishing evidence that sometimes an experienced team needs not so much a youth movement as it does a youth shove. By Game 49, Tuesday night in Chicago, I was ready to accept a clunker. Tuesday night in Chicago, the Mets clunked. It will happen from time to time, even to a club that’s lately had you looking up rather than feeling down.

The 1980 Mets were expected to do nothing. For the first 27 games of their season, they resembled those expectations. Then, for another 18 games, they improved in fits and starts, showing just enough progress on their good nights to leave you deciding the bad nights were no worse than exceptions to the new rule. In Game 45, Pat Zachry and Neil Allen together dueled Jim Kaat of the Cardinals for nine innings at Shea. Kaat was 41 at the time. He scattered six hits and gave up no runs before extras kicked in. Zachry had a two-hit shutout going over seven before giving way to a pinch-hitter. Neil Allen took over and retired his first six Redbirds. Alas, Ken Reitz led off the tenth with a homer, Kaat returned to the mound with a 1-0 lead, withstood a Doug Flynn infield single, and went all the way for the win.

Seventeen-year-old me was prone to processing this sort of outcome as evidence of progress rather than a serious setback. Sure enough, my faith in my 19-26 Mets was about to be rewarded with one of the best week-and-change periods I’ve ever experienced as a fan. It wasn’t just that the Mets went on to win eight of their next ten, it was how they did it. This was the year of the Magic is Back advertising and the week and change ahead turned the wishful thinking motto from punchline to way of life.

The Mets were in the midst of a long homestand. The Cardinals would be followed into town by the defending world champion Pirates, the perennially dangerous Dodgers, and their northern neighbors the Giants. In each of these series, starting with the last game against St. Louis — Game 46 — and running through the middle game against San Francisco — Game 55 — the Mets would stun an opponent by scoring the winning run in their final turn at bat. We didn’t say “walkoff” then, but that’s what was going on: four walkoff wins amid eight wins overall. The Mets kept walking it off, in 21st century parlance, each such finale more stunning than the one before, right through the last one, which still ranks as one of the most stunning results in Metropolitan annals.

That, on June 14, 1980, was the Steve Henderson Game, referenced and remarked upon myriad times since the inception of this blog in 2005. The Mets trailed, 4-0, before ever coming to bat that Saturday night. They were behind, 6-0, when it became an official game. It was 6-2 going to bottom of the ninth. There were two outs and Flynn on second when Lee Mazzilli stepped in versus Giant closer Greg Minton. Mazz singled Flynn home. Frank Taveras walked. New acquisition Claudell Washington drove in Lee, moving Frankie to second. San Fran skipper Dave Bristol removed Minton and brought in Allen Ripley. Ripley’s first batter was Steve Henderson. He was also his last. Henderson crushed a three-run homer over the right field fence, into the Mets’ bullpen, directly to Tom Hausman’s glove. The Mets won, 7-6. The crowd, which wasn’t going anywhere once it absorbed what it had just witnessed, and Henderson, who had retreated to the clubhouse after accepting his teammates’ congratulations, together pretty much invented the Shea Stadium curtain call on the spot. Everybody just kept cheering. They wouldn’t leave until Hendu re-emerged to acknowledge their appreciation. Mets fans who were 17 in 1980 still get chills reliving it in 2023.

A week earlier, when those Mets were getting the hang of upsetting apple carts, their manager, Joe Torre, was dismissive of the leitmotif of the moment: “Magic?” he scoffed to reporters. “I’ve told you all before that’s just public relations.” Now, with Henderson having juiced everybody in attendance to levels of frenzy not felt in Flushing since 1973, Joe from Brooklyn allowed, “It’s really revving people up. Nobody left the park, even when they’re behind by six runs.” Indeed, the next day, nobody could stay away from the park. Not only did the Mets sell every available seat, they had to turn away approximately 6,000 potential customers.

That’s what it’s like when your team picks the right moment to come together and define itself for the better. I’m partial to it happening right around this spot on the schedule, more or less where we are and where we’ve just been in 2023.

In 1969, it was Game 42, coinciding with late-May/early June trip in from the California teams, one being the expansion Padres, the other two being those expatriate New Yorkers, the Giants and Dodgers, who had bullied the actual baby Mets on the reg since 1962. The Mets winning dramatically and consistently against anybody to pull themselves over .500 for good would have been uplifting. That the Mets rocketed toward the heavens at the expense of that pair of tormentors (who’d abandoned nearby boroughs, to boot) made the elevation exponentially sweeter. An eleven-game winning streak and so much more was about to unfurl.

In 1990, the Mets sagged so much for 47 games that it cost the only manager since Gil Hodges to lead them to a world championship his job. Davey Johnson was shown the door at 20-22. Bud Harrelson took over and wasn’t doing a whole lot better guiding what was supposed to be a perennial contender until the eleventh inning of Game 48, when a benchwarmer named Tom O’Malley (batting .091) took Expos reliever Dale Mohorcic over Shea’s center field fence. It was as if the Mets of the 1980s materialized for a curtain call, back in a pennant race on the cusp of what shaped up as one more glorious — or at least quasi-glorious — summer. The team that had been 21-26 entering play on June 5 would be 48-31 coming out of the All-Star break.

In 1980, it was Game 46 when everything beautiful and Magical kicked in. In 2023, it was Game 44. May becoming June. Spring becoming summer. Warm enough to sleep with the window open. Cool enough to keep the air conditioning off. You wake up to a soft breeze, and you’re excited about the Mets, and it will take more than one bump in the road to jar you from the journey to which you’ve emotionally committed.

Yet you won’t win them all. Game 49 in Chicago in 2023 provided a fresh batch of proof. It was a splendid night for Cubs, mostly. For a journeyman starter named Drew Smyly, who threw five smooth innings to climb to 5-1, with an ERA under three. For a former Met pitching prospect named Michael Fulmer. We traded Fulmer for Yoenis Cespedes in 2015 and it was totally worth it, even when the kid we sent to Detroit won the AL Rookie of the Year in 2016 and made the All-Star team in 2017 and seemed to grip a future that would have fit in with what had penciled in for deGrom, Syndergaard, et al., before injuries led him to his role as a 2023 mopup man…which is what he was consigned to filling when at last facing his original organization for the first time. Michael pitched a scoreless ninth in defense of a five-run lead. And for a breakout slugger named Christopher Morel, who seems partial to drawing cat whiskers on his face with eye black. Morel played 113 games as a rookie in 2022 and socked 16 homers. He’s been up with the big club in 2023 for a dozen games and, against Stephen Nogosek on Tuesday night, blasted his ninth home run of the year. Produce like that for a few more dozen games, and you can open for Kiss.

To take nothing away from Morel or Seiya Suzuki or Matt Mervis (the latter two of whom homered off Met starter and loser Tylor Megill), the bat that shouted out loudest in this game belonged to Pete Alonso. It’s not so much that his fourth-inning home run off Smyly cut the Cubs’ lead to 4-1, or that the shot traveled 434 feet from home plate and several rows up into Wrigley Field’s left-center field bleachers, or even that Pete had now increased his major league-leading total to 18, a pace that places him en route to 60. When Pete burst onto the scene in 2019, I tracked his rate vis-à-vis the Met home run record carefully. He shattered that baby (41, established by Todd Hundley in 1996 and equaled by Carlos Beltran in 2006) with little sweat expended and raised it to 53. Once my giddiness from his rookie campaign settled down, I figured that would be the last time I tracked Pete’s homers for season record comparisons, because yo, no way was he going to hit that many again. But for the hell of it, I just looked up when Pete hit his 18th in ’19. It was Game 55, or six games later than this year.

Yet even that’s not the Pete pace I’m thinking of today. What’s really got my attention is that those Magical 1980 Mets, notorious for their power-eschewing offense, didn’t hit their eighteenth home run — I mean collectively — until their 63rd game of the season, and it required the acquisition of Claudell Washington in June, and Washington hitting three home runs on June 22, to get them that many that late in the season. Holy crap, Pete is outhomering the entirety of the 1980 Mets, who, the Daily News enjoyed reminding its readers that summer, were having a hard time matching Roger Maris’s rate from his 61 in ’61; the joke was on them — the 1980 Mets hit exactly 61 home runs.

Steve Henderson’s home run in Game 55, on June 14, was the Mets’ thirteenth and his first of the season. He’d been batting for average (.340), but was a little shy on a particular variety of extra-base hit. That was OK, Steve assured the media. “Home runs,” he said, “are overrated.”

Except when they catapult you from behind and make you recall fondly what eventually crashed into a 67-95 record, which is how the Mets finished 1980, but details, details. I don’t know what the ultimate details of 2023 will be. I do know that despite losing, 7-2, in Chicago and snapping their sensational five-game winning streak achieved at Citi Field, the tenor of this season has been altered for the better. I can’t swear something won’t definitively detract from this current mood over the next 113 games, but what the Mets did versus the Rays and the Guardians and how they did it is likely gonna stay with me when somebody someday mentions this year. I primarily remember 1980 not for the 95 losses in all nor for the frankly pathetic sum of 61 home runs from April until October — nor even for the rather flat performance the Mets turned in during Game 56 in front of a sold-out Shea on June 15, losing, 3-0 to Bob Knepper and the Giants, which is what Game 49 Tuesday night at Wrigley evoked within the realm of raucousness pressing pause. I remember the Magic of the week and change before that loss, never mind the losses to come. I remember the change. I swear, 43 years later, it’s still rattling around in the pockets of my Mets consciousness.

***Even if my fellow veterans of the Magic is Back week and change remember the Steve Henderson Game as if it was yesterday, and even if they nod in recognition of the sellout the next day, they might not be able to identify instantly how that particular seminal series got underway. We had just swept the Dodgers like we were Magic and, as Olivia Newton-John would assure Top 40 listeners in the months ahead, if you were Magic, then nothing could stand in your way. Alas, there was a Giants lefty who absolutely did, putting an end to our four-game winning streak of the moment. His name was Vida Blue.

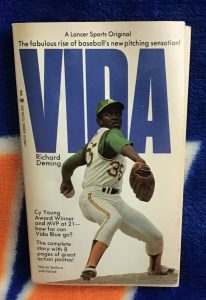

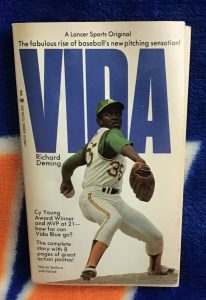

You don’t forget a name like Vida Blue, and you don’t forget a pitcher like Vida Blue. The only Vida Blues I’m aware of were Vida and his father, Vida, Sr. I read up on Vida voraciously when I was nine years old because I followed his ascent breathlessly when I was eight. The lefty for Oakland so mesmerized fans of all ages in 1971, that a paperback book was commissioned for 1972. It was called Vida, written by Richard Deming. Its cover price was 95 cents. I don’t know how much it was listed for when I came across it at a school sale in third grade, shortly after it was published. I do know I snapped it up and read it immediately. It is because of Vida, I know that the phenom who went 24-8 with an ERA of 1.82 was a junior. I know from Vida that Vida, Jr., lost Vida, Sr., in high school.

Vida ran up the porch steps whistling. the front door opened and the whistle died when he saw his mother standing there with his sisters and his brother crowded behind her. He came to a dead halt.

After a moment he said quietly, “Dad?”

Sallie Blue nodded, her eyes brimming with tears.

“Dead?” he asked.

She nodded again, and now the tears began to flow. Then she was sobbing against his shoulder and he was patting her back as though he were the parent and she the child.

“Now, Junior, you’re the man of the house,” she said through her tears.

Broke my heart to read that when I was nine. Breaks my heart to revisit it again. When Vida, Jr., died earlier this month at the age of 73, not long after he’d taken the field in Oakland for a 50th-anniversary reunion of the 1973 world champs during the Mets’ visit there, I remembered that scene, as well as another from the paperback (a book I regrettably discarded in my late twenties but have again today, thanks to the thoughtfulness of a friend who replaced it for me in my early fifties). By this stage in Blue’s story, the southpaw is levitating toward the top of the baseball world, maybe the world at large, and A’s owner Charlie O. Finley comes to him with what Finley has convinced himself is a brilliant idea.

He suggested that Vida have his name changed legally to Vida True Blue, and they would then thereafter use his middle name.

“We’ll take the name Blue off your uniform and have them use True,” Finley said. “And I’ll tell the broadcast boys to call you True Blue.”

As a nine-year-old baseball fan, I was aware of Charlie Finley and wasn’t impressed. This anecdote sealed my disdain. “The broadcast boys…” Yeesh. Vida, Jr., explained to Finley that he was honoring his father’s memory every time he pitched (eventually pitching with VIDA on the back of his jersey rather than BLUE). Finley didn’t push the matter, but did have the Coliseum scoreboard announce before Vida’s next start that “True Blue” would be pitching soon, get your tickets today. Vida got the owner to stop with the shenanigans, “polite” about it, according to Deming, but “quite definite. He did not want to be called True Blue, ever. This time Finley dropped the idea permanently.” Later, according to the author, Vida asked teammates, “If he think it’s such a great name, why doesn’t he call himself True O. Finley?”

Some things just stay with you. Maybe that exchange is why, when the Mets played the A’s in the 1973 World Series, I was all for beating Ken Holtzman and Catfish Hunter, but didn’t take any extra relish in doing damage to Vida Blue. Not that I minded that we won his two starts, in Games Two and Five, but Vida Blue was one of a kind in 1971, and that sort of currency, like a home run in the first third of an otherwise woebegone season, will maintain its place in a person’s heart. When the A’s traded Blue to the Giants in 1978, I was excited to see the lefty make the All-Star team in the National League the way he’d made it three times in the AL and would make it twice more in the NL, including 1980. I wasn’t too happy Blue stanched our Magic momentum on June 13, 1980, defeating the Mets, 3-1 — nor did I care for his postgame quote after he bested Ray Burris that “I didn’t encounter any Mets magic” on Hendu’s Eve — but he was still Vida Blue, the one and only, and here he was, still pitching well when I was 17 after dominating baseball when I was eight. That’s more than half a lifetime at that age.

My final memory of Vida Blue as an active player comes from five years later, right around this time of year in 1985. I was 22. He was 35 and in his second go-round with the Giants, but seemed ancient after an arrest and suspension for cocaine possession sidelined him for all of 1984. The Mets were at Candlestick Park on May 30, Game 52. Doc Gooden was on the mound, just entering that phase of ’85 when he’d be both unbeatable and untouchable. Marty Noble of Newsday, who recognized an angle when he saw one sitting on the opposing team’s bench, sought out Blue to comment on what Gooden was doing. Dwight had just gone the distance, allowing only a run and six hits while striking out fourteen in the Mets’ 2-1 victory over the already hapless Giants.

“Impressive, very impressive.,” Blue said. “The strikeouts were something. What did he have? Fourteen? That’s a lot. But the thing that really impressed me is when he got them — right when it counted most. He closed the door on us when we had a chance in the sixth.”

Yes, in the sixth, Dwight was very much Doc. San Francisco had runners on second and third, with nobody out. But Gooden simply set to operating, popping up ex-Met Gary Rajsich, then striking out Jeffrey Leonard and Chris Brown to get out of what passed for a jam.

“That was the way I used to pitch,” Blue said with touches of whimsy and envy in his tone. “I wasn’t thinking about it much until that situation came up. but I watched him and he tuned up when he had to. That’s what I used to do.”

Blue would finish his big league career in 1986 with 209 wins, never quite the 1971 version of Vida again, but Doc, with an even more phenomenal line to his signature season, was never quite as much Doc again after 1985. How do you stay at the top of the world? If the answer was attainable, it would be permanently crowded up there. Doc’s win over Vida’s team put his record at 7-3, with his ERA dipping to 1.79. You couldn’t be sure 24-4 and 1.53 was where Gooden was headed, but maybe it took one to know one. In talking to Noble at the end of May 1985, Blue labeled his own 1971 “my Gooden year. I had games like this that year.”

That statement was absolutely True.

***Faith and Fear in Flushing has been made aware of a great initiative afoot that can only be described as civic engagement in its finest, purest form: the circulation of an online petition insisting Francisco Alvarez — “barring a huge erosion in his offensive production” — not be sent down to solve any supposed logjam of catchers once Omar Narvaez and Tomás Nido return from the injured list. Should this cause sit close to your heart, please visit the petition’s page and consider signing. As its argument asserts, “Roster flexibility is nice, but winning games is better.”

by Jason Fry on 22 May 2023 4:28 pm I was in Boston this weekend for my niece’s med-school graduation, which meant the Mets took a back seat to family doings. But not much of a back seat, seeing how it was me and all — the Mets went about their business in my ear, via GameDay and my watch face, on my phone in a ceremonial tent, and finally right there on an honest-to-goodness TV as I urged them to hurry.

Friday night’s game was the most catch as can catch — I was dining solo when a friend couldn’t make it last minute, and confined myself to a couple of peeks at the score while at the restaurant, with those couple of peeks suggesting I might have picked the right game to miss. But after dinner I put on MLB Audio and let Howie and Keith narrate for me from down around my hip. (Forgot my damn AirPods.) I heard Brett Baty homer to make things a little closer (following the lead of fellow Baby Met Francisco Alvarez), then heard Dominic Leone get into trouble and Stephen Nogosek seem to get out of it — except I’d turned off the game to catch up with my brother-in-law and his sister and when I looked at my phone again, the roof had caved in on Nogosek, with the Mets’ two-run deficit having doubled to four.

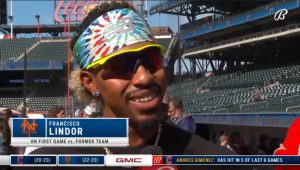

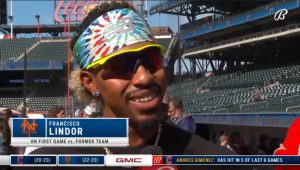

Except then the next peek showed that 7-3 had somehow become 7-7. For the 10th I propped my phone up and let GameDay do its thing, which was to bring grim and apparently fatal tidings, followed by miraculously good ones. Mark Vientos! Eduardo Escobar! Alvarez! Brandon Nimmo! And then Francisco Lindor, that former Cleveland baseball ambassador, now spreading the good news about the game in a new town. The Mets had won, I allowed myself a few boozy fist pumps, and then hoped I had enough battery life left to get a Lyft. (Nah, but it was a nice night, so I walked and thought good thoughts about the Mets.)

Saturday’s washout left me as your double chronicler for Sunday, an uncertain business given that Sunday was Graduation Day. The first half of the game went by largely without me, though a couple of phone peeks were enough to reveal the sigh-of-relief news that Max Scherzer was pitching well. I was sitting in the tent when GameDay offered grimmer tidings: Adam Ottavino had spat the bit, allowing a 3-0 Met lead to become a 4-3 grumblethon.

Which was when I remembered that I could watch MLB.tv since I was out of the Mets’ blackout zone. We were still in the milling around/parents awkwardly marking saved seats portion of Graduation Day, so why not? I was watching using my cell signal, so the video was variable to say the least: crystal-clear one moment, like looking through the murkiest pixel fog the next. (Plus I had no sound — forgot the damn AirPods again.) The video was in one of its fogged-in periods at the critical moment, but I’ve watched enough baseball to learn the visual language of production trucks: A blocky Starling Marte swung, the pitcher looked up through the blurriness, the camera switched to a wide shot of the outfield wall, and I stomped my feet happily in the grass. David Robertson came on, worked around a spot of bother and the game ended with a harmless fly to Marte — just in time, as it happened, for the pomp and circumstance to begin.

The second game begins with a confession: I don’t much like any of the changes to baseball instituted by Rob Manfred and his merry band of MBAs, ranking them somewhere on the spectrum between unnecessary and insulting to reason. But I was looking back and forth from the Mets’ scheduled start time to the 9:20 boarding time for my flight back to New York and wondering if I might be able to pull this off. The game wouldn’t be over by the time I got on the plane, but when you added the time needed for passengers to screw up stowing their luggage and get told to put away their laptops and if I accidentally on purpose ignored the Airplane Mode announcement … well, it was possible I’d hear the final out before wheels up and so not spend the flight in a state of anticipation and ridiculous hunting for auguries. (Do those scudding clouds look a little like Nimmo diving for a ball? What does that mean?)

I listened at first, feeling for Howie when the inevitable happened and he transposed the names belonging to Justin Verlander and Shane Bieber to suggest a certain pop star had a new career. (S. Bieber is certainly handsome enough to be a teen idol, so why not?) I heard the sound made by Jose Ramirez’s bat connecting with a ball in the first inning and so wasn’t particularly surprised by word that said ball had landed basically on Mars. But after that Verlander was brisk and relentless, sending Guardians away from the plate after the briefest of interactions.

The problem was that Bieber was also brisk and relentless — here was an old-fashioned duel of aces, and never mind the bigger bases and limited disengagements and not allowing fielders to play where charts tell them makes sense to play. The game was half-done by the time I settled into the Delta Sky Club and asked the bartender if he could turn on ESPN.

I was just in time to see Lindor get the Mets even with a golf shot of a homer, and from there I let the game unfold visually across the room without sound. The Mets had tied it, with Verlander going eight innings — a sight both wonderful and unexpected given his new team’s rotation woes.

Tied it, but my boarding time had gone from “still a ways away” to “awfully soon now.” Then Alvarez singled off Bieber — our fireplug catcher seems to be in the middle of everything, doesn’t he? — and turned into Marte, who in rapid succession survived a near-pickoff and then scampered to third on a little cue shot through the infield by Lindor. Jeff McNeil brought Marte home on a sac fly, with Brooks Raley coming in for the save — and my 9:20 boarding time now just a few minutes away.

Raley turned a nifty play to spoil Steven Kwan’s bunt attempt, and on just a single pitch, no less — I thanked him for both. But then he hit Amed Rosario, bringing up Ramirez and his by now lengthy track record of damage. It was 9:18. My boarding time was in peril, but larger things were too.

Ramirez hit the second pitch of the AB — and just the fifth of the inning — directly at Lindor for the old tailor-made 6-4-3 double play. The Mets had won in a little more than two hours, which I’ll grudgingly note might of had something to do with Manfredball. I grabbed my bags and walked downstairs and straight onto the plane with a certain spring in my step.

And why not? The Mets, seemingly dead after following their three-week brownout with an opening loss to the Rays, have now won five straight, all of them one-run decisions. They’ve done it thanks to precocious play from the celebrated Baby Mets but also with contributions from wise old heads — it was Alonso and Lindor and Marte and Scherzer and Verlander who came up big against the Guardians.

I don’t know what it portends — this season has been decidedly peculiar, with the Mets either looking unstoppable or unbearable. But all of a sudden they look once again like the team that was so much fun in the spring and summer of 2022. GameDay graphics, audio burbling away in my pocket, murky cell video, an actual television — if they keep playing like this, I’ll find a way to accompany them.

by Greg Prince on 20 May 2023 6:23 am In the spirit of the Baseball Writers Association of America members with whom I rubbed or at least grazed elbows Friday night, I humbly submit my ballot for Most Valuable Angle from the 10-9 ten-inning Mets win over the Guardians.

1) MY PRESENCE IN THE CITI FIELD PRESS BOX

This first-place vote may seem like the height of self-absorption, but a) blogging is foremost a first-person medium; and b) the Mets are 7-0 when I cover a ballgame from the Citi Field press box (high-rolling craps players have gotten less for their money from gorgeous good-luck charms they pay to blow on dice). More pertinently, the Mets win some of their craziest bleeping games when I’m wearing a credential around my neck rather than my heart on my sleeve. Rule No. 1 of the press box is there is no cheering, not even by a member of the media whose medium is all about advocating for the cause of the home team. I’m a seasoned pro when it comes to tamping down my rah-rah impulses, having taken those aforementioned crazy bleeping games in remarkable stride, at least until the credential came off my neck and the shouts emerged from my larynx.

2) INTERLEAGUE IS DEAD

I was Working Press for a night because I had an idea or two I wished to pursue, among them the notion that what was once conceived as a novel avenue toward boosting fan interest in the course of a long season is now so commonplace that it doesn’t matter. Seven National League clubs played seven American League clubs on Friday. Same as Wednesday. It’s not “Interleague Week,” the way it was introduced to us in 1997. Every week has a bunch of matchups between NL and AL, creating a wallpaper effect. Maybe the intracity showdowns are still big news. Maybe the chance to see Shohei Ohtani in, I don’t know, Cincinnati, is a godsend to Reds fans. Otherwise, we’re in NFL/NBA/NHL territory wherein team from this conference plays team from that conference and it’s business as usual. Thus, I wanted to get credentialed for the opener of this Mets-Guardians series so I could ask Buck Showalter, a manager whose dugout experience predates Interleague play, if the onslaught of 29 different opponents across the schedule presents new challenges to his preparation (and we all understand how critical preparation is to Buck). I asked, and he gave me a really good, really detailed answer around 4:30 Friday afternoon that doesn’t seem all that relevant given the events transpiring around 10 o’clock Friday night, but he confirmed my suspicion. Buck admitted, “I don’t even think about it anymore” whether it’s an NL team or an AL team next on the Mets slate, and credited “the advance people” for being on top of such a plethora of potentially unknown quantities. Despite it fading into the background as Friday’s festivities went along, this angle gets my second-place vote because it tickled my curiosity enough to get me to the ballpark and on assignment.

3) SILENT NO MORE

The other angle that lured me to Citi Field Friday night was the appearance of the leading light of the Silent Generation Mets. Those were the 2020 Mets who weren’t Mets before or after the short but depressing pandemic year, meaning they never knew what it was like to play as Mets in front of fleshed-out Mets fans. All the likes of Billy Hamilton, Jake Marisnick, Guillermo Heredia, Hunter Strickland and Erasmo Ramirez knew from were cardboard cutouts. I mention those Mets of recent, quiet vintage, because they have at least come back to Citi Field as former Mets. None made much of an impact in 2020, so none really drew a rousing ovation in ’21 or ’22. Ah, but Andrés Giménez was a veritable force as a 2020 Met, the youngest kid on the roster making a name for himself and his future. Andrés played in 26 of 30 home games as a heady infielder on the rise, even rating a smidge of Rookie of the Year support in the succeeding offseason’s BBWAA balloting. Then he was traded before a single fan who might have applauded for him while watching him on television could do it in person. I thought it would be instructive to see and feel Giménez immersed in an authentic Flushing din. Let’s say he now knows what Citi Field really sounds like.

4) YESTERDAY’S FUTURE

Giménez was traded in a package that included the Met shortstop he was in the process of making superfluous, Amed Rosario. Rosario was the breakout star of our dreams way back in 2017. That long? Or is it only that long? We know how we are about demanding a hot prospect be granted his immediate promotion; we didn’t just invent that impulse this year. Rosario’s installation on the active roster was a happening. The Mets followed up with Rosario-themed giveaways. As he progressed, you couldn’t picture our future without Amed. Then one day he was deleted from our present. It warms my heart to report Rosario, like Giménez, received tangible applause when the starting lineups were announced Friday night. More a trickle than a flood, but neither of them was treated like an American League stranger (no video, though). After Rosario’s first-inning hit, a sing-song chant of “Jose! Jose! Jose!” went up. Could it be the crowd remembered Rosario as protégé to Reyes and was making a meta-comment on the circle of Met life? No, it was just some Cleveland supporters excited to see Jose Ramirez come bat next. Guardians groupies would find a lot to get vocal about in the minutes ahead.

Always a giant matchup. 5) ECHOES OF 1954

The “Cleveland” wasn’t the Indians, the “New York” wasn’t the Giants, and the Polo Grounds is a housing project in 2023, but geographically if not in precise name, we had a World Series rematch on our hands: CLE (AL) at NY (NL). One last glint of sepia-toned romanticism to frame the Mets-Guardians matchup in the glow of memories forged when Willie Mays made The Catch, Dusty Rhodes delivered The Pinch-Hits and the National League champions upset the supposedly unbeatable junior circuit behemoth in four straight. Random Interleague matchup? We had a tradition to uphold! Or, perhaps, just a third consecutive game to win in the midst of what had been, until very recently, a morbid May. “Still,” Arnold Hano wrote in A Day in the Bleachers, the book that made the 1954 Fall Classic a true classic, “I’m not an American League fan. All I know about the Indians is what I have read about them in the papers.” During my night in the press box, I noticed the official scoresheet listed the Mets’ foes for the evening as the “Cleveladn” Guardians. I feared word would get down to the visitors’ dugout and Terry Francona would use the typo as motivation.

6) HE DIDN’T GET HIS MEN

Carlos Carrasco, off the injured list, replicated Sal Maglie in one respect. Both the Giants’ starter from Game One of the 1954 World Series and the Mets starter in the first of three games set for this weekend (weather permitting) gave up first-inning runs. In that respect, Maglie would have fit in nicely with the 2023 Met rotation. Maglie — “the Barber” — got nicked for two runs out of the gate, then shut down Cleveland through seven. Carrasco — Cookie — didn’t compensate for his early crumbles so effectively. Carlos had the Mets trailing, 4-0, after two and 5-0 after he completed his night’s work after five. We could only hope our bullpen had enough Don Liddle and Marv Grissom to it should the Mets’ bats mount any kind of comeback.

7) BABIES COME BACK

Five fine innings from Cal Quantrill (even better than what Bob Lemon posted to open Game One in ’54), combined with the five runs Carrasco gave up, were too much for the Mets to handle…or would have been, before the Mets commenced to reinvent themselves as full of spit and vinegar — and adamant about never saying die. These Mets aren’t your grandfather’s Mets. Or your father’s. Or your older brother’s. Or yours from Monday or Tuesday. These are the Mets who got it together on Wednesday, kept it together on Thursday and gave no indication they didn’t plan to keep it rolling on Friday. How? With an infusion of blood so young it could get a base hit for two different teams in two different cities off two Hall of Fame pitchers on the same day. Francisco Alvarez, 21, went high and deep in the bottom of the fifth. Nobody was on base, but the run Alvarez drove in didn’t stay lonely for long, as former kid who still plays like one Jeff McNeil drove in another run. It was 5-2 heading to sixth — and 5-3 heading out of it, thanks to Brett Baty, 23, homering to lead off the home half of the inning. Climbing out of holes is suddenly a Met skill set. Toddlers love to climb, right?

8) NOTHING POLARIZING ABOUT IT

Having generated such a thoughtful response from Buck pregame, I wondered if I could ask him a followup in the seventh: “What’s this debilitating fascination you have with Dominic Leone?” Leone, who hasn’t inspired an iota of confidence during his Met tenure to date, got bailed out by his defense in the sixth. He responded to his good fortune by loading the bases in the seventh. Stephen Nogosek was the next safety net. It almost worked, too. Rosario lined to center, but Nimmo (who’d performed a little Maysian magic on a Wertzian drive from Giménez) caught it and fired home. Baserunner Will Brennan found himself trapped in a rundown. Alvarez threw to Baty, who chased Brennan toward the plate before tagging him out. In the books, that’s an 8-2-5 double play. That’s the stuff of Dykstra to Gibbons to Hojo, speaking of New York (NL) teams to have won it all. Alas, Nogosek wouldn’t eradicate what was left of Leone’s mess, and the Guardians took a 7-3 lead to the bottom of the seventh. Pete Alonso then took that lead and turned it to dust. Grand slam!!!! Four runs!!!! Tie game!!!! (Exclamation points abound here because in the press box, remember, no cheering.)

9) PITCHING AND DEFENSE

So Leone and Nogosek weren’t the Liddle and Grissom of their day. Liddle threw the pitch that Vic Wertz blasted to most distant center only to have Mays track it down; Grissom was the pitcher Leo Durocher brought in after him, with legend having it that Liddle told Grissom as he vacated the mound, “Well, I got my man.” Most importantly, the two Giant relievers from 69 years ago didn’t allow Cleveland to add on to their two runs. That’s the kind of performance the Mets needed ASAP. It’s what they got just as quickly from Adam Ottavino in the eighth — no baserunners, which was great, because an Ottavino baserunner is an automatic Ottavino basestealer — and David Robertson in the ninth. Robertson in particular was assisted by fancy fielding, with McNeil robbing Steven Kwan, and Alonso squelching a base hit bid by Ramirez. The two pitchers doing their best to add up to one Edwin Diaz were half of the reason the game was heading to extras. The other half? The Mets didn’t score in the eighth or ninth, either.

Lindor in the middle of everything, including me (in windbreaker over the shortstop’s left shoulder). 10) THE DRAMATIC RATHER THAN TRAUMATIC CONCLUSION

Drew Smith took a step outside the bullpen circle of trust, giving up a two-run homer to Gabriel Arias (after Rob Manfred put a Guardian on second) in the top of the tenth to almost certainly make the night an exercise in highs and lows that would land with a thud on a low. Unless you were nutty enough to foresee a nutty conclusion to what had been a fairly nutty game through nine-and-a-half. I was sitting in the same press box I was sitting in when Alonso tore off Michael Conforto’s shirt after Conforto and Todd Frazier tore the roof off the Citi sucker in 2019; when Joey Votto hit a ball off the top of the outfield wall rather than over it on the night 1973 Met stalwart Jon Matlack was inducted into the team Hall of Fame in 2021; and when the Marlins threw all the goodwill they could at the Mets and away from each other on Keith Herrnandez’s number retirement day in 2022. Those were all highlights of unfathomable walkoff wins. How on earth could you expect the Mets to match those kinds of heroics?

• First, you call Rob Manfred and ask for a runner on second, and magically appears Brett Baty.

• Then, you cope with the presence of Emmanuel Clase, the American League’s answer to Edwin Diaz in 2022.

• Then, you send up your Most Valuable Met from 2022, Starling Marte, but it’s a new year, and Marte flies out to right. At least it’s enough to move Baty to third.

• Then, you make with the spit and vinegar again, via the third of the Citi Kids, as I’d taken to calling them in my head. Mark Vientos, 23 and DH’ing (we’ll overlook what a miserable role that is to inflict on a veritable child), singles Baty home. It is 9-8. By never saying die, death is averted.

• Eduardo Escobar comes into pinch-run, no slight detail. The Mets have not had their pinch-running specialist Tim Locastro for weeks and won’t have him for more weeks (thumb problems while on rehab). Escobar, the displaced veteran, carves out a niche as the base thief of record. He steals second, setting up a marvelous opportunity for pinch-hitter Daniel Vogelbach.

• Yeah, right. Vogelbach strikes out.

• But here comes Alvarez! Except Alvarez, after two pitches, is in an oh-two hole at the plate, and up in the press box, Mr. They Never Lose With Me Here unplugs his tablet from the handy outlet of which he’s been availing himself all night because this reporter knows it’s a lost cause and maybe he can get a jump on the commute home if he starts to pack up before the inevitable becomes a reality.

• And, I swear, as soon as the charger’s prongs were detached from the electrical socket, Alvarez socked the next pitch he saw into left, scoring Escobar with the tying run. The detached observer up in the press box plugged his tablet back in.

• Nimmo grounds near but not to Rosario. Amed doesn’t have enough time to nab the ball and Brandon, meaning it’s first and third.

• After Buck’s presser and before settling into my press box seat, I took a trip out onto the field. You can do that when you have the right credential around your neck. Between the reporters and the photographers and the various guests the Mets welcome and the perk-enjoying season ticket “members,” there may be more spectators surrounding the field during batting practice in Flushing than there are in the stands during games in Oakland. Even this ad hoc crowd was bigger than any Giménez saw when he was a Met. One fellow amid all this activity stood out. He’s got the hair for it, the bandana for it, and the charisma for it. Francisco Lindor attracted attention, whether he strove for it or not. He stopped to give an interview for Cleveland’s pregame show. He stopped to greet families who couldn’t believe the Mets’ shortstop was not only talking to them but smiling at them. He invited two children to come see “my office,” meaning the clubhouse, and whisked them on a whirlwind tour. Lindor was already doing it all and first pitch was still two hours away. As focused as I was on Rosario and Giménez coming home, it was a much bigger deal for the Guardians and their fans/press corps that they’d be facing the players they sent to New York: Carrasco and, especially, Lindor.

• Lindor was a big deal in Cleveland for a reason and is a big deal in New York for a comparable reason. The man comes through. Even after interrupting his pregame preparation to accommodate everybody. Even while having to wear an olive drab cap that doesn’t go with his dyed curls (or anybody’s natural ones), let alone black jersey. Even when the Mets appeared in various states of dead and desperate.

• The erstwhile Clevelander turned on the nightlife in Queens, singling home Alvarez — who Francisco labeled one of the “Baby Mets” with the winning run. I like Citi Kids as a moniker (I’m already seeing the poster in my head), but the important thing is we’re test-driving adorable names because we’re so excited about these adorable young players and their adorable elders. Together, the generations made it Mets 10 Guardians 9 in ten. Two nights after Mets 9 Rays 8 in ten. Sandwiching Mets 3 Rays 2 in nine. All one-run wins are not created equal, but each of these one-run wins has been huge in its own right, and this version takes its place in the pantheon of press box EXTRA! EXTRA! READ ALL ABOUT IT! special editions, the kicker coming from both out on the field, where “L.A. Woman” blared like it was 1999 (followed by “Takin’ Care of Business” evoking 2006) and back in the Excelsior concourse where, whenever somebody opened a rear door, you could hear LET’S GO METS!!! rumble down the steps from Promenade.

So yeah. A good night to cover a ballgame.

by Greg Prince on 19 May 2023 12:08 pm I followed Thursday afternoon’s game from Citi Field as much as I possibly could, and it followed me almost but not fully everywhere I had to go. Thursday afternoons can be uncooperative that way. I had TV at the beginning and end, radio on and off in the middle, and pitches missed here and there. My attention was focused no more than three-quarters Metwise at any given moment. That’s an estimate; Statcast doesn’t measure fan focus, but give them time. Despite gaps, I was able to discern that the Mets and the Rays clung close to one another all day. Had my attention pierced the 90% mark, I might call the game tense, but I was partly distracted; fairly content that the sun was out; and, mostly, not convinced the Mets would eventually lose. That state of affairs on its own merits depleted for me some of the tension from a matchup whose margin never exceeded one run. As a Mets fan, I was simply happy not being unhappy.

If that’s not a sea change, it’s a least a tidal shift. For several weeks until the late innings Wednesday night, Mets games proceeded mostly on a doom course. They’d lost 16 of 22. Few of the sixteen losses as they unfolded seemed surprising. Almost all of the six wins came off as aberrations. Even going back to the smugger beginnings of the season, including the spurt when we collected 11 Ws in 14 attempts, I was increasingly overcome by something being no less than slightly off about this team. A virtual pie to the face to the first person who haughtily sees fit to remind me that all wins are good wins. You didn’t have to graduate first grade to comprehend all wins are preferable to all losses, yet there were wins in whose fabric flaws are noticeable and nagging. I keep going back to the Saturday (3-2) and Sunday (4-3) of the sweep in Oakland and the conviction I developed that weekend that if we’d been playing anybody better than the consensus pick for worst team in baseball, we could have been had. Soon, we’d be playing a string of teams considered barely a notch above the A’s, and the whole assortment of presumed also-rans tangled us in knots.

What it says when the Mets, after stumbling successively at the hands of the Tigers, the Rockies, the Reds and the Nats, were thrown into competition versus the consensus best team in baseball and, eventually, got the best of the best I’m not as sure. The Rays made the Mets look as bad Tuesday night as the Nationals made the Mets look Monday afternoon. A lot of bad had been going around and it didn’t ask to see anybody’s record as it descended on the House of Not So Amazin’. The Mets, behind Kodai Senga on the mound and the Rays on the scoreboard, didn’t look bad Wednesday night so much as destined to be outlasted. Senga pitched great, yet the Rays kept finding ways to edge ahead. Then here came the latest iteration of the Youth of America, clutch Mark Vientos and even clutcher Francisco Alvarez, and suddenly we were in fugazi extra innings, and a Rays run scored easy-peasy, and the best team in baseball was positioned to inflict upon us one of the least appealing consolation prizes a professional sports team of whom much was expected can receive: a moral victory. No, we didn’t beat the mighty Rays, you could hear it reasoned, but the kids came up big and it took ten before we went down for the count.

As one imagines Pete Alonso would put it with characteristic eloquence, fuck moral victories. With a synthetic runner (Brandon Nimmo) on third and a real one (Jeff McNeil, by way of a single to right rather than a baseball-hating commissioner’s bright idea) on first, Alonso sent a Pete Fairbanks pitch to somewhere near Anchorage, and, as you know, we won, 8-7. Without Pete’s explicit power, maybe we lose, 7-5. Or maybe they lose, 7-5. Pronouns can be tricky when you don’t necessarily wish to identify with a particular result.

What Wednesday night’s triumph accomplished, beyond one win, was to make Thursday the kind of game when, no matter what percentage of attention you directed toward it in amid the contours of an afternoon, mentally tenable. It helped that the slight hole the Mets dug for themselves in the top of the first (they sure love to dig first-inning holes) wasn’t deep and it was instantly excavated in the bottom of the first. The two teams traded a run apiece. The two starters, Tylor Megill for our side, Taj Bradley for theirs, settled in. I knew nothing about Taj Bradley going in. I knew Megill as well as one could from three seasons of intermittent pitching as a guy we use mainly because somebody else isn’t available. I know that he can, from time to time, provide an island of stability for a staff in disarray. Tylor was all that on April 12, when he went five solid innings and gave up but two runs to the Padres in a hypercompetent 5-2 win at Citi Field.

That game was the thirteenth the Mets played in 2023. The season’s ensuing episodes have since, like Terence Mann’s evocation of America in Field of Dreams, rolled by like an army of steamrollers. As of April 12, the Mets had yet to make that ten-game trip to the West Coast, Max Scherzer had yet to be suspended for sweat and rosin, Justin Verlander had yet to make a single start and the ballclub had yet to utterly lose its way. As of April 12, the Mets were 7-6, clearing their throats en route to announcing they were a week and change from catapulting to 14-7. It was the day I figured the Mets were now the Mets and everything was gonna be fine. It was the last time I allowed myself to feel the slightest bit smug about our projected powerhouse of a surefire contender. It was the last time I thought Tylor Megill was an unalloyed asset to the rotation.

Until Thursday. Megill going six against the Rays and giving up two runs was the main reason for feeling good about Megill. The Mets withstanding the Rays on all fronts seeded the environment for greater satisfaction. Because of how they played Wednesday — because of how they finished Wednesday (not just in the tenth, but within the thunderbolt swings of the seventh and the ninth) — I had the sense I was watching/listening to a different team from the one that had sapped the enthusiasm out of the season for most of the past month. Maybe we won’t win, I thought, but it won’t because we so readily allow the worst in us to come out at the slightest tap. Better yet, maybe we won’t lose, regardless that these are the Rays, and for all of Tuesday and most of Wednesday we were made to understood what that meant.

The Rays of Thursday were pretty good, too, but so were our Mets. Their first-inning run was met by our first-inning run. Their next run, in the sixth, served only to match the one Pete put up all by his lonesome in fourth. The Rays’ response, via Josh Lowe’s solo homer, tied the game at two, but it didn’t severely damage our chances in the interim. Megill hung tough enough, and the Mets, à la the Fabulous Thunderbirds, still maintained a chance to wrap it up.

In the bottom of the sixth, as in the bottom of the first, the Mets scratched out a run, this one to put them/us ahead, 3-2. It’s the Alonso blasts to the heavens and the Vientos and Alvarez breakthroughs that you remember, but it’s the simple little rally tally that can make all the difference. Alonso’s non-homer batting average is .152. Be glad that Pete leads the world in home runs with 16. Be thrilled that once in a while his teammates, young and less young, go deep. (The thrill of a non-Pete Met homer being so rare helps explain why track-record slugger/tin glove catcher Gary Sanchez is coming up, presumably at the expense of Michael Perez, who merely instigated the final defensive out of the top of the sixth with a heady pickoff throw to first.) But danged, as Pete likely wouldn’t say, if three singles stitched together by McNeil, Baty and Pham — none of them calling for the kind of Statcast tape-measuring Alonso’s hits require — don’t also sometime get the job done.

Same for three innings of unglamorous but mostly effective relief pitching, this time around from Brooks Raley, Jeff Brigham and David Robertson. Tampa Bay put a runner on first in the eighth and another runner on second in the ninth. I was prepared for the dang dam to burst at any given moment, with Rays runs swimming everywhere, but I was just as prepared to stay dry. Each arm did what it was asked to do. No Ray scored after the sixth. The Mets had just won two in a row.

The standings tell us almost nothing definitive other than they contain only 45 games played for the Mets to this point. The “race’ for the final NL Wild Card involves literally everybody who isn’t already clutching a playoff spot in the mythical if the season ended today… derby. Miami, in what amounts to first place for Berth No. 6, is five games ahead of eleventh-place Washington. Washington’s probably not going to get hotter than ten other clubs and become the third Wild Card in the league, but you can’t tell the Nationals to go home and get their shine box on May 19. Nobody’s out of it yet. That, blessedly, includes us. We’re 22-23. It would be nice if we could keep adjusting the first column upward and limit the rise of the second. Nice for now is a return to actually believing such a Met-friendly trajectory is more than possible.

This is where, if the season was in further progress and straits had just grown slightly less dire from two encouraging victories, we might declare, YOU GOTTA BELIEVE! Too early for that in 2023, but not too early to pay tribute to the 50th anniversary of the season when both our lexicon and our flagpole was enhanced forever. Revisit the pennant-winning campaign of 1973 as part of the It Happens in Threes series on the newest episode of National League Town.

by Jason Fry on 18 May 2023 12:28 am For most of Wednesday night, my only thought was that feeling pain because of the Mets was actually progress: better writhing in agony than sitting dour and numb watching another night of bad baseball, as we have for the last three and a half weeks.

Kodai Senga was the best he’s looked as a Met, with command of every pitch in his arsenal and an apparent bit of extra intensity. (Maybe it was all the family members in the stands — given Joey Lucchesi‘s first scintillating start in San Francisco, perhaps every Met starter needs a retinue of relatives in attendance.) But the Rays pierced Senga for a lone run in the fourth and that looked like it would be enough to beat him, because the Mets couldn’t do anything with Josh Fleming or Kevin Kelly. The sixth was particularly frustrating — Jeff McNeil pinch-hit and walloped a drive to left-center that annoying showboat Jose Siri ran down, Francisco Lindor singled, but Pete Alonso grounded out and Daniel Vogelbach looked utterly helpless in a lefty-on-lefty matchup with Jake Diekman. When Siri smacked a homer off Jeff Brigham an inning later, the crowd at Citi Field seemed too depressed to boo.

The ball hit to center by freshly anointed savior hasty import newly arrived Mark Vientos off Ryan “No Not That One, He’s Like 75 Years Old by Now” Thompson looked destined to wind up in Siri’s glove, undoubtedly to be followed by Siri turning several cartwheels and blowing kisses to his teammates. But somehow it kept carrying until it was safely over the fence: Implausibly and wonderfully, the kid had done what we’d been clamoring for him to do here instead of in Syracuse and the Mets had tied it.

Well, for about five minutes. Adam Ottavino didn’t have it, walking Randy Arozarena and looking perturbed as Arozarena swiped second, one of seven Rays to steal off Mets’ pitchers — phrased that way because Francisco Alvarez was at fault for exactly none of them. When Brandon Lowe — I forget if he’s the Lowe pronounced like OW or the Lowe pronounced like the oh in OH NO — homered off a slider that slid its way into trouble, Citi Field felt like a funeral home, with the faithful stunned into silence.

I was on my couch, but I knew I looked like all the fans SNY’s cameras lingered on: a dull stare above the rigor mortis of surrender. I rarely stalk away from even terrible games, but I won’t claim that’s the product of superior moral fiber; mostly it’s because I’m old and a certain long-haul fatalism has crept in. But OK, it’s also because there’s still a better me somewhere inside this gloomy old hulk, and that better me always has to be blowing frantically on some sad little ember of hope and chirping annoyingly that it’s not over yet and anything is possible and wouldn’t you feel like a chump if one of those 1,000-to-1 bets placed out of stubborn belief paid off and you missed it?

Because sometimes — OK, once in a very great while — those bets actually do.

Even when you’re playing the best team in baseball, the one with the relentless hitters and the pitiless base swipers and a million relievers throwing from two million weird angles, and you let that team tack on a ninth-inning run to leave you three in arrears, with the three feeling more like 30.

In the bottom of the ninth Jason Adam was tasked with facing Vogelbach, Starling Marte and Mark Canha, not exactly a trio to spark fear this year. But he walked Vogelbach and hit Marte before striking out Brett Baty, sent up to pinch-hit for Canha. Vientos flied to center and the Mets had used 26 of their precious outs, with only one left. All that stood between the Mets and another defeat was Alvarez, whose rapid improvement has yet to include not trying to do too much in big spots.

Alvarez spat on a sweeper just outside for ball one, which was mildly encouraging; Adam tried that pitch again, left it middle-middle, and Alvarez demolished it, smashing it off the facing of the second deck to tie the game. He unleashed an epic bat flip and floated around the bases, levitated by the swagger that’s made me laugh since I first glimpsed him as a Brooklyn Cyclone not so long ago.

A wonderful moment, except it lasted about as long as the afterglow of the previous game-tying homer from a rookie. Against David Robertson, ghost runner Taylor Walls swiped third leading off the 10th, came in on a Harold Ramirez single, and then Ramirez came home on a single by the other irritating Lowe. Robertson had been all but untouchable all year, but that one looked like a dagger. Sure, there’d be hopeful things to say about Vientos and Alvarez and Senga would earn well-deserved praise, but the Mets seemed fated to lose another one.

McNeil led off the 10th against Pete Fairbanks with a single, pushing ectoplasmic Brandon Nimmo to third, but Lindor looked hapless striking out on a pitch in the dirt and up came Alonso — who was “sick as a dog,” we’d learn later from Buck Showalter.

Fairbanks’ first pitch was a slider that caught a lot of plate, except Pete was looking fastball and it zipped in untouched.

“That might be the best pitch he sees,” I grumbled.

A wonderful thing about baseball is sometimes you’re completely and utterly wrong and it makes you happy. Fairbanks’ next pitch was the fastball, he threw it to the exact same spot as the slider, and the second Alonso made contact you knew the game was over — impossibly and unbelievably and blissfully over. This is baseball’s greatest magic trick: a slow, grim forced march to a seemingly inevitable unhappy ending somehow transformed in an instant and become stammering, staggering joy.

The Polar Bear stomped around the bases and vanished into a forest of helmet pounds and high-fives, with one SNY shot catching Baty, Vientos and Alvarez in the same frame, romping out of the dugout beaming and impossibly young. Pete offered up his postgame LFGM for Steve Gelbs’s mic, except this time he said the words and not the letters, including the word that I assume will draw a fine from the FCC* and tut-tutting from the ranks of the self-appointed tut-tutters.

Another reason it’s good to have a billionaire owner? I’m pretty sure Steve Cohen will pay the fine without so much as a blink. I’m tempted to chip in myself — maybe even enough for the triple play pancake breakfast. And I know there will be a next however many games when all looks dark and dreary but I stay at my post, obeying that little voice, the one that simultaneously annoys me and that I hope I never stop hearing, the one insisting that anything is possible and wouldn’t you feel like a chump if you missed it?

* the FCC’s fining/grousing is limited to broadcast, smarter people tell me. Carry on, Polar Swear!

by Jason Fry on 16 May 2023 11:44 pm The Mets said all the right things after getting beaten by the Rays 8-5 on Tuesday night in a game that was not nearly as close as the final score suggests. Justin Verlander talked about understanding the fans’ frustration and about how the players were frustrated too and about needing to work hard. Buck Showalter talked about worms turning but didn’t sugarcoat all the things that seem to be going wrong all at once. It all sounded good, but if you zoomed out from trees to forest, the vibe was essentially that the beatings will continue until morale improves. And when exactly will that be? The starting pitchers are dropping their teammates in holes early, the hitters have stopped hitting and so are unable to slug their way out of those holes, and this dreary blueprint is followed pretty much daily, leaving the games sour and unwatchable.

Predictably, a Mets team that had just been steamrolled by the not very good Nationals found the Rays a tough matchup. Right now the Rays are pretty much a perfect baseball team: They ground down Verlander, a surefire Hall of Famer even if he won’t wear our uniform on his plaque, until he was forced to make hitters’ pitches, which the Rays didn’t miss. Meanwhile the Mets hit three home runs, which is three more than they hit in Washington, but that was all they did, and this moderate uprising never really felt like a serious threat — frankly, it was a lot of lipstick to waste on one pig. The Mets got screwed on a replay challenge at first, they got booed repeatedly by the faithful, and in the last few innings SNY treated us to about 200 shots of Mets fans looking outraged, astonished, morose or catatonic.

If that’s the scale, I think right now I’m somewhere between the last stages of astonished and early-onset morose — the Rays are a fantastic baseball team, the Mets are a tire fire, and it’s a little like the unstoppable force and the unmovable object if you switched the polarity of one of those entities so that both were pushing in the same direction, which is to say away from the Mets conceivably winning anything. I mean, Starling Marte looks done, Mark Canha remains a shell of his 2022 self, Daniel Vogelbach‘s best moment was cheering a teammate, Francisco Alvarez‘s swing is getting worrisomely long again, Drew Smith had a fit in the dugout … it’s bad, y’all.

Congratulations to Josh Walker, I guess, for becoming the 1,200th Met all time. Now that Walker is a made man, though, he’s strongly advised to run like hell away from this Baseball Chernobyl. Maybe see if Tampa Bay could use another arm — those guys look like they’re going places.

by Jason Fry on 16 May 2023 7:46 am A confounding Mets season took another confounding turn Monday afternoon, when the team followed up Sunday’s burst of offensive competence (counterpoint, maybe the Nationals decided to experiment and do Whip-Its between innings) by once again looking like an outfit with zero resemblance to a professional baseball team. Going into Monday, you might have said, “Well, at least we know David Peterson isn’t really a pitcher with a 7.68 ERA.” And you’d be correct — when the Nats were done strafing Peterson, leaving him lying in a daze on the mound surrounded by the components of his uniform, a la Charlie Brown, he was a pitcher with an 8.08 ERA.

8.08! I’m no statistical wizard, but that seems bad!

Peterson will soon be out of a job, replaced by Carlos Carrasco. I take no satisfaction in pointing out at this juncture that Carrasco’s 2023 ERA is … 8.56.

And yet Carrasco now somehow feels at least sort of savior-adjacent. That’s because Peterson has been a metronome of suck, so chronically and reliably horrible that when I hear his name I now reflexively assume the posture of a (much smaller, not even faintly intimidating) bouncer outside of the kind of downtown hot spot I don’t go to. Right now I never want to see him again, a stance that is neither personal nor permanent, but heartfelt for all that.

But it’s not all Peterson’s fault, not by a long shot. He’s one guy having a bad season, a label that could be liberally applied to the Mets roster. We could point to the starters who haven’t started, the starters who have started and fizzled, the home-run hitters who have done nothing to earn that distinction, the 2022 offensive stalwarts who have gone flabby this year, or just to the general rancid crumminess produced by the collective. Since the last two days of their at-the-time-heartening California trip the Mets have been terrible at all aspects of baseball, putting up a 6-15 record against the Giants, Braves, Nats, Tigers, Rockies and Reds.

They now have to face the Rays, who could fall out of a boat and discover that 26 guys can walk on water. In baseball youneverknow, to quote the late Joaquin Andujar, but you can often guess, and let’s just say I’m not filled with optimism. As things have cratered, I’ve been thinking about another old baseball saw: the idea that you spend the first two months figuring out what you have, the next two getting what you need and the last two seeing what you can do.

The end of May will more or less mark the end of the Figuring Out What You Have part of the schedule. A turnaround from this same group of players is possible, and would be no weirder than other things that have happened in this strange Girl With a Curl campaign. (Recall that these same Mets were 14-7 before whatever the hell happened halfway through San Francisco.) But barring a strange and heartening turn, you’d expect the Mets’ braintrust to conclude that what they have is not what they need, and so start making changes. Maybe that means Mark Vientos and/or Ronny Mauricio join Brett Baty and Francisco Alvarez for a ’23 youth movement, which seems risky but once again, it’s not exactly going well; maybe it means pink slips for some veterans; maybe it means some big move empowered by Cohen cash flow; maybe it means some combination of those things; maybe it means something else entirely.

The end of May might feel a long way off while Rays are pell-melling around the bases and the Citi Field faithful are booing anyone down on the field unwise enough to be caught wearing blue and orange. But it really isn’t a distant prospect — it’s 14 games away, which measured by new fast-forward Manfredball standards is about 36 hours.

Thirty-six baseball hours from now, one suspects, the 2023 Mets will start looking different.

Maybe better, maybe worse, but different. And why not? As I believe I and more importantly they have demonstrated, it’s not going well.

by Greg Prince on 15 May 2023 12:39 pm On May 9, 1972, it rained in New York, which, then as now, is an unfortunate occurrence when a baseball game is scheduled in the Metropolitan Area. The Mets were to play the Dodgers at Shea Stadium that Tuesday night, meaning that baseball game would have to be made up. The good news was the Dodgers would be sticking around Queens for a couple of days. They had games scheduled Wednesday night and Thursday night. With no significant travel on their itinerary — their next stop was scheduled to be Philadelphia — it wouldn’t put anybody out if a twi-night doubleheader was scheduled. Instead of opening the gates for an 8:05 PM start, the norm in 1972, the Mets could invite fans to be in their seats by 5:35 PM for the first pitch of the first game, and then continue to maintain those seats as theirs through the final pitch of the second game. Such adjustment to circumstances by the management of the home team was traditionally one of the unexpected bonuses of a given baseball season. You didn’t expect there to be two games for the price of one on that date when you saw the schedule at season’s beginning, but sometimes you’d get a chance to partake. What a bargain!

Author Charlie Bevis, a baseball historian of all things night-game related, breaks down the utility of the twi-nighter on his incredibly informative website, explaining its application peaked between 1942 and 1972, when the NL and AL were shifting from almost exclusively day games to mostly night games. “The twi-night doubleheader originally developed to facilitate the makeup of postponed games,” Bevis writes. “The potential problem with night baseball was the postponement of a night game, since teams couldn’t just add on another night game as they easily could to an afternoon game, since spectators would not tolerate the second game starting very late at night.”

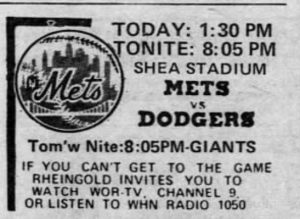

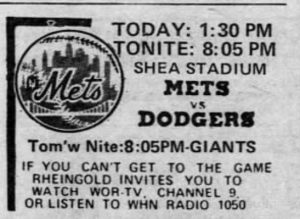

A ready-made answer hence existed for the Mets. Ah, but M. Donald Grant, running the show, had or at least signed off on a different idea. Perhaps because a players’ strike had lopped a few dates off the front end of the season, or perhaps because the Dodgers were too enticing a draw to make him tolerate losing the receipts they usually generated (a reluctantly hosted makeup doubleheader versus L.A. from the previous August might have remained fresh in the chairman’s mind), Grant approved a Shea Stadium first: a split doubleheader on Thursday, May 11. Mets and Dodgers at 1:30 PM, with all fans clearing out when that game was over. The second game would be at 8:05 PM, as scheduled. Each would require its own ticket. No freebies in Flushing this Thursday. No bargain.

Two for the price of two the first Met time. Coverage of baseball might not have been as consumer-friendly or at least as consumer-conscious as it is today. Reporters in the press box didn’t have instant access to what fans were thinking nor were they necessarily compelled to find out. Thus, when one plumbs various archives, one comes up empty in search of explanations for why, in the Mets’ eleventh season, they are suddenly deciding to charge two admissions for two games in one day after, for ten seasons, hewing to the beauty of two for the price of one, sometimes on purpose (Sunday doubleheaders were fairly standard), sometimes out of rainy necessity. In Boston, the Red Sox regularly held day-night doubleheaders when compelled by the weather, but that was understandable. Fenway Park was comparatively tiny in the emerged age of multipurpose stadia. With about 32,000 seats and decent demand, you maybe wanted to make sure every possible fan in New England could be accommodated amid a ticket squeeze. Shea held 55,000 or so seats. People weren’t likely to be left altogether out in the cold if a date went by the wayside somewhere between April and October. Rainchecks could do wonders in an enormous outdoor facility. Joe Trimble in the Daily News provided the most service journalism in this realm by detailing Thursday morning a little what would be different at Shea Thursday afternoon and evening.

“Incidentally, the matinee begins at 1:30 p.m., 35 minutes earlier than usual for a day game. The reason is obvious. The cleaning crew has to have time to sweep up the house. Season ticketholders must use coupon E-1 today. No tickets were printed for today’s game as it wasn’t on the original schedule.”

While the Mets beat writers didn’t explicitly address what the heck Grant was doing here, a reader more than a half-century later can discern more than one raised eyebrow. After covering a 14-inning affair on Wednesday night that lasted until close to midnight Thursday (“by the slender margin of 10 minutes, the Mets lost a chance at a unique tripleheader sweep”), Joe Gergen in Newsday alluded to the upcoming day-night doubleheader, attributing its scheduling to “Tuesday night’s rainout and a new management policy.” What the policy was may have been edited for space or never chronicled in the first place, but a person gets a sense that “new management policy” is code for Grant grubbing money. The Times didn’t seem to think much of what the policy wrought, with its non-bylined story devoting its fourth paragraph of ten to noting, “The two games — two for the price of two — were watched by a total of 28,732 persons, not many for a rivalry with ancestral overtones. Only 8,299 paid to watch the afternoon half of the program, a makeup for Tuesday’s rained-out game, and 20,433 turned out at night.” Indeed, during the last series in which Mets hosted weeknight games against the Los Angeles Dodgers of no longer Brooklyn, in June of ’71, paid attendance topped 35,000 twice.

Once the two-for-two occurred, there didn’t appear to be much followup on the subject of Shea’s experiment with day-night doubleheaders in the local media. To be fair, there was a lot going on in Metsopotamia that week.

• There was that 14-inning game on Wednesday, won by the Mets on Teddy Martinez beating out an infield single following Buddy Harrelson stealing second and taking third on a wild pitch, all after Tug McGraw pitched five innings of shutout relief. “It was a long night,” Harrelson observed in the home clubhouse as the calendar pushed forward. “It was almost a long tomorrow.” There was, too, the quick turnaround for that day half of the split-admission extravaganza ahead. (Gergen: “McGraw still was in his underwear at 12:30 and he was due back at 11:45 AM.”)

• There was the Mets’ win in the day portion Thursday which featured Tom Seaver’s 100th career victory, achieved despite what had become chronically aching legs; imagine how terrific Tom would be feeling totally healthy.

• And, oh, there was the little matter of a trade the Mets were working on with the team that was coming into the Shea once the Dodgers left town after the nightcap (which L.A. salvaged to not make their stay in New York a total washout). The Mets and Giants were talking through a deal that would send one of San Francisco’s high-priced veterans back east so he could finish his career in the city where he started it. The Giants weren’t having a great season and weren’t drawing well. The Mets could afford him and, though he wasn’t the player he was in his prime, the 41-year-old’s appeal was undeniable. You might have heard of him. His name was and is Willie Mays, the Say Hey Kid who recently turned 92. Although the Giants were playing in Montreal, Mays had his club’s permission to fly ahead to New York to get involved in the talks himself. Everybody had to be satisfied by the brewing transaction that was filling newspaper column inches Wednesday and Thursday. On Friday, May 12, Willie, in a suit and tie, was on the back page of the four-star edition of the News, pictured sitting in the press box taking in the Thursday afternoon action in the company of the sparse crowd; Grant presumably didn’t charge him to count among the 8,299 who went through the turnstiles. Willie appeared to be watching intently. He should have been. Those were his new teammates down on the field. The Mets had swung the deal for Mays on May 11, 1972 — exchanging pitcher Charlie Williams and a reported $100,000 in cash — the day that doesn’t primarily go down in franchise history as the day Tom Seaver notched his hundredth win nor as the day the Mets experimented with day-night doubleheaders.

Willie Mays watches history at Shea just before making his own. The experiment lasted a combined 18 innings. The Mets went back to making up rainouts the old-fashioned way, with single-admission doubleheaders, or as we old-timers call them, doubleheaders. On August 1, the Mets and Phillies played a twi-nighter to compensate for a rainout from the end of May. As if karma was trying to get a message to Grant, the first game of this twinbill lasted 18 innings and nearly four-and-a-half hours on its own, and the teams couldn’t play the nightcap until between-games festivities were completed. It was Banner Night, with 2,176 bedsheets and placards marched through the center field gate. Game Two (a 1:45 Koosman-Carlton special executed sans pitch clock) didn’t end until 12:45 AM. Thankfully for the players, August 2’s lone Mets-Phillies game was scheduled for 8:05 PM.

Shea Stadium wouldn’t host both segments of another day-night doubleheader until 2007, when pretty much every team resorted to split-admission twinbills if the weather was uncooperative. The Mets could reasonably tell their customers that with attendance riding high in the ballpark’s final two seasons of existence, they sure wouldn’t want to shut out raincheck holders who might not be able to turn in their vouchers for a comparable seat so easily. In 2009, the Mets would move into a smaller ballpark, where the same argument could be made with an approximately straight face. Fans, particularly those who didn’t grow up in the age of single-admission doubleheaders as essentially the only kind of doubleheaders, didn’t think anything was particularly unusual about this kind of double-dipping into their pockets.

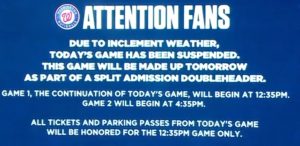

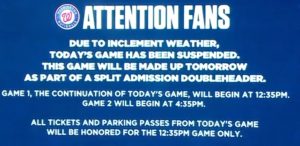

Yet nobody could instantly remember anybody doing to its ticketholders what the Washington Nationals did on the weekend of May 13-14, 2023. The Nats, who provided the opposition when the post-Grant Mets revived the split-doubleheader experiment at Shea on July 28, 2007, sanctioned the starting of their game versus the 2023 Mets this past Saturday at 4:05 PM despite ongoing rain. Maybe it would pass. It didn’t. The tarp went on the field within 40 minutes of first pitch, in the top of the third inning. It came off more than two hours later. The grounds crew came out and worked to make the field playable. It was no longer raining, but nobody was playing. People sitting on hold amid a loop of “your call is important to us…” had more of a clue as to what was going on in their endeavors than did anybody curious as to whatever became of Saturday’s contest. Ultimately, just short of four hours since play was stopped, the game was suspended. It was still the third inning, the Nationals ahead, 1-0. The Mets had runners on second and third. Daniel Vogelbach on third base and Michael Perez on second had the good sense to come in from the rain. But they and their colleagues would return to the field the next afternoon, the environs sunny and dry. It hadn’t made for an ideal scenario — not starting in the first place and preemptively rescheduling didn’t require much hindsight to anybody staring at the sky or a weather app — but these things happen.