The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 11 May 2023 12:47 am The New York Mets currently have on their roster five pitchers who were born before their last world championship, which speaks to both the age of the pitchers and the last world championship. One, Max Scherzer, hasn’t been able to make his most recent scheduled start because of neck spasms. One, Tommy Hunter, missed time in the bullpen because of back spasms. The team, not quite treading water to date, has chalked up its successes spasmodically at best. At one point, the Mets won 11 of 14 this very year. You might not remember that, given that they followed up that stretch by immediately losing 12 of 15.

Good thing, then, that they had the pitching Wednesday night in Cincinnati to pull them closer to sea level. All three arms on which they relied were attached to babies born prior to October 27, 1986. The babies grew up to become major league hurlers with uncommon amounts of experience, at least as measured in places other than the 2023 New York Mets clubhouse. On these Mets, you don’t flinch when told the pitchers in action were born in 1983, 1985 and later in 1985.

You’re just glad they’ve been around long enough to know what they’re doing.

When Justin Verlander was born, on February 20, 1983, Tom Seaver hadn’t pitched for the Mets since before the Wednesday Night Massacre. Darryl Strawberry had not yet played a single major league game. Keith Hernandez was ensconced as the first baseman of the defending world champion St. Louis Cardinals. Everything we’d come to associate with 1983 and the Mets — Seaver’s triumphant Opening Day return; Strawberry’s hotly anticipated promotion; Hernandez’s sudden arrival by midseason trade — was in the future. Baby Verlander came first, forty-plus years ago.

Then Old Man Verlander waited a while to make his Met debut, not only by spending his first 18 seasons in Detroit and Houston, but then shaking off a teres major strain for a month. We didn’t know from teres when Verlander went on the IL a couple of hours before the first pitch of the new season. We could have guessed missing him would be major. So it was. When you have a righty who’s won not only two World Series and three Cy Youngs and made those totals current within the last twelve months, you want to see what he can do for you.

In his first start, he endured one inning that had us scanning the fine print to see if his megacontract came with a refund clause, then settled down to remind us what a fully developed, reasonably healthy starting pitcher looked like. Had the Mets hit for him at all in Detroit, his two runs over five frames would have looked mighty good. They seemed fairly satisfying even in a loss.

Six days later, Justin faced another opponent he seemed readily capable of steamrolling, but we’ve been just as susceptible of rolling over for alleged bottom-feeders, middle-dwellers that we’ve become. The Reds hit plenty the night before, but that was off David Peterson, a.k.a. pitching depth. Verlander’s the front line, or was going to be had not teres major ordered him to the sidelines. Wednesday night, his entire body was back in form. Another shaky first inning, but maybe that’s his m.o. at the moment. When Seaver would encounter danger, then limit damage in a first inning, you nodded that things would probably be OK. Get to the great ones early or not at all.

The Reds got to Verlander in the first inning, for one run, then not at all. Somewhere along the way at Great American Ball Park, the 40-year-old locked in and made calendar pages irrelevant. On this occasion, Justin went seven innings in a Mets uniform, which is something only Joey Lucchesi had done among starting pitchers in 2023. Of all the new sensations Justin Verlander looked forward to as a New York Met, aspiring to match Joey Lucchesi for length probably didn’t top the list.

Thank goodness he did, though. Verlander gave the Mets the best start they’d had this season, two hits over seven innings, just that one run in the first, hardly a baserunner from the second inning on. Thus inspired, the Mets offense supported him…barely. Pete Alonso, who seems to take to steamboat architecture and the siren song of the mighty Ohio, hit a solo shot to tie the game in the second. The Mets otherwise mostly left runners here and there, but in the fourth, they accidentally strung together a double from Luis Guillorme, a walk to Francisco Alvarez and a single by Brandon Nimmo — all with two out — to take the lead. The Mets would leave eleven runners on base in all. Consider the two that crossed the plate manna from heaven.

Consider Verlander’s successors, the similarly venerable Adam Ottavino (37) and David Robertson (38), sentries worthy to stand watch over the manna. Holding an edge of 2-1 after seven, in the wake of losing 12 of 15, didn’t make one think, “This would be a great game to win!” No, this would have been a terrible game to lose, because to lose it would be to tell Verlander he really shouldn’t have stopped by on his way to Cooperstown, while hinting to the rest of us that we shouldn’t expect much to get better soon.

Fortunately, good old Adam and slightly better, slightly older David were both very much on. Plus the Reds are pretty crummy. Sooner or later we were bound to meet the enemy and it wouldn’t be us. Ottavino’s eighth was clean. Robertson’s ninth was spotless. Having tethered their lines to Verlander’s effective seven, we were treated to a rare three-man two-hit victory. How rare? Dismissing rain-shortened or pandemic-truncated doubleheader versions, Baseball-Reference’s Stathead tool tells us the Mets have now won two-hitters via three pitchers thirteen times in their history. It happened only once prior to 1998, because it used to be (when Verlander, Ottavino and Robertson were kids) that if you had a starting pitcher working on a two-hitter, he kept working on a two-hitter. The only pre-modern iteration of the three-to-give-up-two combo occurred in 1968 when Jim McAndrew went eight-and-a-third before Gil Hodges turned to Bill Short and Cal Koonce to retire one batter each to top the Cubs, 1-0.

Such specific combining wouldn’t happen again for thirty years, when the starter was Masato Yoshii and the relievers, for an inning apiece, were Greg McMichael and John Franco. The Mets beat the Cardinals that night, 4-1, on a two-hitter. What the 1968 game didn’t have; and the 1998 game didn’t have; and what none of the ten three-man two-hit victories that followed between 2001 and 2022 had that Wednesday night’s in Cincinnati featured was this much experience. The Mets had never before won a three-pitcher two-hitter in which each pitcher was a member of the 37 & Up Club. The life experience was implicit. The baseball experience was off the charts. Verlander’s been in the majors since 2005, Robertson since 2008 (he made his big league debut at Shea), Ottavino since 2010. From the vantage point of 2023, that’s a lot of years and a lot of innings, starting in one case, relieving in two others. That, as we’ve already seen this year, tends to place the risk in front on the risk/reward scale. Older pitchers had to do a lot to last as long as they have and still be trusted at this stage of their career. To ask them to defy chronological gravity as a group is trusting them even more. For a night, it absolutely worked.

On this night, it really had to.

Two Mets pitchers who may have been an even bigger deal than Justin Verlander are in the spotlight on the latest episode of National League Town. One retired last week. One made a comeback the week before. One you heard about everywhere. One you had to be watching a particular cable network to know from. Come and listen to the story of two aces too good to be true.

by Jason Fry on 9 May 2023 10:52 pm The Mets have been both bad and unwatchable for the better part of two weeks, so Tuesday night counted as progress: They were watchable.

Watchable, as they fought back after being put in a deep hole by David Peterson, Stephen Nogosek, and (one could argue) the umpiring crew, which missed a ball headed for Francisco Lindor‘s glove hitting Wil Myers in the hand as he slid into second. Intentional? Probably not. Against the rules? Certainly. Enough to make Buck Showalter mad? Oh yeah. Buck was ejected for the first time as a Mets skipper and at least got his money’s worth, indicating via a one-two-three-four pantomime visible across the river in Kentucky that four umpires had been on the field and not one of them had managed to fulfill the basics of the job.

Showalter departed dissatisfied, Nogosek gave up a two-run triple and a sac fly, and somehow it was 7-1 Reds, as the Mets continued their ill-advised run of making the dregs of the major leagues look like world-beaters. Seriously, since the wheels came off in San Francisco the Mets have lost series to the Nationals, Tigers and Rockies, and they’re now off on the wrong foot against the Reds, the sole remaining entity on Earth that hasn’t received the memo that drop shadows are out.

Down by six, the Mets did at least fight back: Posterity will record that they scored five unanswered runs. Unfortunately, mathematics will record that they needed to score one more than that. Francisco Alvarez started the futile comeback with his second homer of the night, with additional runs courtesy of homers from Pete Alonso and Lindor and a run-scoring GIDP by Mark Canha. That GIDP wound up typifying too much of what’s been happening, though: It came with the bases loaded and nobody out in the seventh, short-circuiting the inning, and Canha fell on his face after stumbling across first base.

In other words, it was the last two weeks of Mets baseball distilled into about eight thoroughly shitty seconds.

Elsewhere, well, where do you want to start? Peterson, called upon after Max Scherzer was scratched with neck spasms, looked like he’d been replaced with a heretofore unknown identical twin who had no idea how to pitch. He couldn’t throw strikes and when he somehow did you wished he hadn’t. Peterson’s short career has been marked by false starts and reversals, to be sure, but he looks absolutely lost right now, a young pitcher whose stuff, location and confidence have all deserted him. It was cruel summoning him from Syracuse when that’s pretty clearly where he needs to be, but the Mets had no choice — and, in case you weren’t already depressed, he was filling in for a guy who’s destined for the Hall of Fame but hasn’t exactly looked like himself all year either, which is starting to look like a much bigger problem than Peterson’s growing pains.

As for the Myers play, a basic equation of baseball and life is that when you’re going horseshit they fuck you. The Mets have demonstrated proof of the numerator for two weeks now, so getting smacked in the face by the denominator isn’t injustice but simple cause and effect.

by Greg Prince on 8 May 2023 12:38 pm In the Mets’ first four seasons, the club twice lost home games by a score of 13-6. The first of them, on May 30, 1962, marked the coming out party for a chant you might hear enthusiastically when the Mets are coming on strong or ironically when the Mets pausing from going down meekly: “a full, furious, happy shout of ‘Let’s go, Mets! Let’s go, Mets!’” This explosion of emotion, captured by Roger Angell in his first season occasionally covering baseball for the New Yorker, burst into the Polo Grounds atmosphere after Gil Hodges led off the bottom of the fourth with a home run that cut the home team’s deficit to 10-1.

Ironically enthusiastic? Enthusiastically ironic? Maybe more than a little defiant, given that the opponent was daring to show its face again in the city of New York after abandoning our town for better weather and better parking. Whatever the mechanism of the motivation, Mets fans were into it and the Mets went on to lose to the Los Angeles Dodgers of no longer Brooklyn, 13-6.

The second of such losses occurred three seasons later, this time at Shea Stadium against the Reds, on September 14, 1965. If Angell attended this particular defeat, he did not incorporate into any of the essays that constituted his breakout book The Summer Game. Summer was effectively over in New York by mid-September of ’65. Cincinnati’s pennant hopes were still alive. The Mets’ chances of playing meaningful games in September weren’t yet as much as a gleam in the eye of even the most anticipant fan. Not that patience was altogether in abundance. Chanting wasn’t the story at Shea that night. According to the not yet villainous Dick Young in the Daily News the next day, the pertinent sentiment of evening could be found on a two-sided banner.

Side A

GIVE US A TEAM, NOT A DREAM

Side B

PROMISES, PROMISES

The Mets entered play at 46-100, ensuring a fourth consecutive season of triple-digit losing. It’s hard for the hardiest of crowds to not come prepared to express dismay when the novelty of cheering anything and everything that isn’t consistent winning begins to wear off. A 13-6 loss, even to a contender, is a kick in the teeth of good nature, even if your team is down only 8-5 heading to the ninth.

Especially if your team is down only 8-5 heading to the ninth.

Much would happen between the Mets falling to 46-101 on September 14, 1965, and the Mets waking up to a record of 17-17 on May 7, 2023. The Mets have never otherwise been 46-101 (praise be) nor 17-17 (quite curious, considering they’ve been 18-16 eleven times and 16-18 six times). They also had lost only once at home in that span by that score of 13-6.

I know. I was there.

The date was August 12, 1982. I was two weeks from returning to college for my sophomore year, so I was intent on cramming as much Mets into my system as I could before departing. Tuesday night the Twelfth was going to be the first of three games for me over the course of five days, attendance frequency not at all unusual in the seasons to come, absolutely unprecedented in my life when I was nineteen.

Also unprecedented: standing on the ticket line outside Shea and being approached by somebody looking to get rid of a pair. He was a reverse scalper. Had two tickets — plus Diamond Club passes! — and simply needed to dump them. He’d give them to my friend and me for five bucks each, or two dollars less than the face value of a Field Level box seat in 1982. Although it seemed a little good to be real, we accepted the hard bargain. The tickets were real. First base side, very good view of the Mets and Cubs.

We didn’t avail ourselves of the Diamond Club passes (the fine print indicated we would have had to have dressed for a session of the General Assembly at the United Nations to have passed muster at the door), but the game was enough. The Mets were trailing, 3-1, until a sixth-inning rally punctuated by a John Stearns double that pulled the Mets to within a run. George Bamberger proceeded to send up Rusty Staub to pinch-hit for Ron Gardenhire after Dallas Green ordered Dickie Noles to intentionally walk Hubie Brooks to load the bases and one out. National League strategy; there was nothing like it. Green was angling for a double play ball. Rusty had a different, better idea, slamming a double to right and clearing those bags. The Mets led, 5-3. Jubilation reigned. I can’t swear “Let’s Go Mets!” arose from all the box seats, but I’m pretty sure it did from mine.

Swearing, however, would follow in short order, as the top of the seventh brought on a Cub rally that dwarfed the one Rusty capped. Chicago scored eight runs off four Met pitchers. Staub’s clutch double grew smaller and smaller in the rearview mirror. What was developing into the greatest Shea Stadium experience I’d ever had to that point dissolved into familiar angst. Just one run after another scoring off one pitcher after another. Orosco replaced Scott. Leach replaced Orosco. Falcone replaced Leach. Misery replaced ebullience. Two drunk business types a few rows down thought it was hilarious in that way people automatically laughed at the Mets. One biker type sitting closer told the business types to cut it out, but in language and with menace that I believe convinced the business types to call it a night before the seventh-inning stretch.

The Mets went on to lose, 13-6. I returned as planned Thursday night and Saturday afternoon. The Mets lost those, too. But never again at home by that same score.

Until Sunday, May 7, 2023, a day that at its start had only one obvious element in common with August 12, 1982. I was there. I’ve now been there for exactly half of all Mets home losses of 13-6 in their 62-year history.

Unlucky score. Lucky me.

No, really. I’m sitting here 41 years since 1982 and recalling at no additional harm to my psyche what it was like watching the Mets dramatically grab a lead and then be assaulted a half-inning later for all their lunch money. Yet I’ll never forget the victory of the seven-dollar box seats costing only five bucks, nor the righteous anger of the biker type, nor Rusty doing what Rusty did in a pinch.

The 13-6 loss I could have done without, but you can’t have everything. Or sometimes get saddled with a little too much.

You need a gargantuan scoreboard to fit a combined 19 runs. From the game of 41 years later, I could do without the 13-6 loss the 2023 Rockies pasted on the 2023 Mets. I could do without Joey Lucchesi no longer being a pleasant surprise. I could do without the march of mediocrity the Mets’ bulging middle relief corps represents almost daily of late. Even when Buck Showalter’s veritable Lotto drawing pulls up an occasional solid inning among your Hunters, your Brighams, your Leones and your Yacabonii, we’re playing those numbers far too often. Lucchesi, who was removed from a so-so outing in Detroit on Wednesday to make sure he’d be available to provide a so-so outing in New York on Sunday, lasted four innings (felt like three).

Admission to Sunday’s 13-6 loss cost me five dollars less than admission to the one from 1982. I was a guest at a Party Deck soiree, courtesy ultimately of a friend of a friend whose company was having an outing far better than Lucchesi’s. Also courtesy of my friend’s wife who opted not to take in beautiful weather and iffy baseball, thus the empty bar-style stool just waiting for me to top it. No stuffy business types in evidence. These are the seats in right and right-center where children — and adults briefly taking on the behavioral patterns of children — wave their arms to get the attention of outfielders who might be convinced to throw a baseball their way between innings. Every time Brandon Nimmo was entrusted with that opportunity, he sought out a genuine child and made an accurate toss. For that, Brandon Nimmo is my player of Sunday’s game.

Don’t know if you can make it out from this angle, but if you focus, you can see a bonehead play developing. No other Met garnered much consideration, despite the three-run bottom of the first that immediately erased a 1-0 Rockies lead off Lucchesi. The Mets were reaching base so routinely (and I was sitting so far from the infield) that I began to lose track of who was where. For example, when the Mets were up, 3-1, and Luis Guillorme had singled to right with two out, I was sure he had driven in Brett Baty from second. You know who wasn’t? Rockies right fielder Kris Bryant, who threw purposefully to second, as purposefully as Nimmo did to the kids in the stands. A “4” did not go up on any of the scoreboards, including the enormous one over my left shoulder. A groan of discontent went up from all seating sections.

“What happened?” I asked my friend. “Did Canha get tagged out at second?”

“No,” he told me. “Vogelbach.”

Like I said, there had been so many baserunners that I briefly lost track of who was where. Canha had made an out before Vogelbach reached first. Vogelbach made an out after reaching second, rounding the bag — with Bryant more alert to it than he was — before Baty could cross the plate with that fourth run. Vogelbach was tagged out first.

Score at the end of one: Mets 3 Rockies 1.

Score at the end of nine: Rockies 13 Mets 6.

So forgive me if I gloss over the details of the trajectory of the game from the second inning forward and share with you instead a few other observations from my first trip to Citi Field this season.

• The main video board, which swallowed dainty little Citi Vision, is indeed gargantuan, but once you get used to it, it’s seems the right size for baseball, what with baseball being the biggest thing in our lives.

Nothing’s sacred. • While I needed a few innings to just adjust my senses to watching the infield from all the way out in the outfield, I pretty quickly noticed that one of the ribbon advertising boards that wraps the seating bowl flashed a logo for New York-Presbyterin. That’s their typo, not mine. It was spelled “Presbyterian” in every other iteration across the ballpark, but “Presbyterin” on the one above and behind home plate. Make a sleeve patch out of that, why don’t you?

• Basic ballpark food is included with a Party Deck affair, but unlike those obnoxious car ads that deride basic, I’m here to tell you, per Humphrey Bogart, that a hot dog on the Party Deck beats roast beef at the Ritz, and I don’t need to know from the Ritz to assert this truism. I know from Citi Field. That was one of the venue’s better hot dogs, and it was accompanied by an even better box of chicken tenders.

• I learned at least one genuine coupon good for one Carvel Ice Cream Sundae in 1984 still exists in mint condition because it was not “redeemed at the appropriate station” at Shea by 3 PM on its day of issuance. Another friend of my friend who invited me produced a photo on his phone of said Strawberry Sunday voucher, issued to celebrate Darryl’s Rookie of the Year campaign the year before. He’s willing to donate it to the Mets Hall of Fame. I say he should take it to a Mr. Softee stand at Citi — before 3 PM, of course — and see if it will be cross-honored à la the MTA when something’s up with the subway and/or LIRR.

Is it ever too late to celebrate Strawberry Sunday? • Arithmetical skills notwithstanding, I also learned that it’s been 40 years since Darryl Strawberry was a rookie.

• I also learned there’s a limit to my Mets fan patience when eleven losses have piled up in fourteen games. Perhaps extending himself past second base for no helpful reason whatsoever moved me to articulate it, but I told my friend, “I’ve never said this out loud, but I [bleeping] can’t stand Daniel Vogelbach.” I don’t think I said “hate”. I hope I didn’t say hate. There’s nothing hateful about Daniel Vogelbach except he’s such a [bleeping] DH, and I still [bleeping] hate the DH, and I can’t believe he so thoroughly personifies the position I [bleeping] hate so thoroughly, right down to rounding second on an obvious RBI and then not getting back to the bag in time to let the runner score.

• When Vogelbach later hit one of those Estée Lauder home runs that altered the blowout loss no more than cosmetically, I theatrically applauded and cheered because I felt kind of bad about admitting the unkind thoughts I’d been harboring for weeks. “Let’s go, VOGEY! Let’s go, VOGEY!” Also, it was a Met home run and I’m not made of stone.

• My friend who invited me, who wouldn’t quite join me in my animus for Vogey, suggested quite sincerely that slumping Pete Alonso be sent to Triple-A for seventeen days to a) preserve another year of service time; and b) get Mark Vientos up here to play first, which would c) set up Alonso to DH, which I suppose would take care of my Vogelbach problem. When you’re en route to losing, 13-6, and falling under .500, there are no sacred cows. Or Polar Bears. Or the spellings of leading religions.

• Fantastic weather. Brought a jacket. Didn’t need it. The weather shares Player of the Game honors with Nimmo.

First game of the year in The Log I keep of every home game I’ve ever attended. Hopefully not the last. First 13-6 loss in The Log in 41 years. Hopefully the last ever.

by Jason Fry on 7 May 2023 10:02 am The Mets, all $430-odd million of them, are a mess.

The hitting is anemic. The starting pitching is mediocre. The record is the literal definition of mediocracy. The vibe, not an official stat but readily detectable, is a lot worse than that, with fans increasingly fuming before taking their seats, looking for someone to blame and finding no shortage of targets.

It ain’t good, folks.

It ain’t good, and after you’ve shelled out approaching half a billion, fixes probably aren’t coming from outside. Brett Baty and Francisco Alvarez are already here. Justin Verlander is back. Expecting poor Mark Vientos to be a savior seems cruel; ditto for Ronny Mauricio. Improvement will have to come from within.

And you know what? It probably will — the gremlins of sequencing will afflict some other team, guys will play more to the back of their baseball cards than they have in a month and change, and buzzards’ luck will turn to whatever the opposite of buzzards’ luck is. (I’m imagining those cheerful little bluebirds that help out Snow White.)

Or maybe none of that will happen, and 2023 will go down in the annals as one of those years when Too Much Went Wrong, a bump on the road to future glory or a flashing warning sign to the downturn that in retrospect we’ll of course all have seen coming. Baseball in the moment is a strange beast, doing what it does attended by a swarm of observers’ stories zooming this way and that; we impose the rules of narrative on it when looking back, which baseball shrugs off because it’s moved on to a new present formlessness.

That’s a wordy-ass way of saying nobody knows. Right now the Mets are not good and not fun, something that unfortunately everybody knows.

* * *

Bill Pulsipher threw out the first pitch in Saturday’s game — the same Bill Pulsipher who a million years ago was part of Generation K, arriving alongside Jason Isringhausen and Paul Wilson to form a triumvirate of arms that were going to be the rock upon which rose a new Fortress Mets.

That never happened — the trio combined for less than 100 Met starts, and were never on the roster at the same time. At the time we argued equivalents, discussing who was Seaver and Koosman and Matlack; as it turned out all three guys were Gary Gentry, Exhibit A for the caution that ought to attend each and every young flamethrower.

A couple of baseball generations later, the memories of Generation K are almost entirely sad or bad. There’s Pulse and Izzy hurling balls around the field with reckless abandon, ignoring John Franco‘s prescient warning that they’d hurt their arms. There was the day the Mets caught a rehabbing Isringhausen playing co-ed softball for a team sponsored by a strip club. There was Wilson getting left in too long by Dallas Green against the Cubs and surrendering a Sammy Sosa homer that turned his imminent first triumph to ashes. And most of all there were injuries and reversals, self-inflicted and team-negligent and simply random. Pulse went from prospect to suspect, hanging on for a variety of teams as a spare part. Injuries reduced Wilson to ordinary with cruel speed. Only Isringhausen forged a notable career, and that was as a reliever. (Look back here, if you dare.)

Pulse was at Citi Field on Saturday for Mental Health Awareness Day, a concept whose mere acknowledgment by MLB would have been unthinkable in the days when Generation K stumbled across the earth. Between innings, he talked about his struggles with Steve Gelbs, offering an admission that struck me for its honesty: He’d felt anxiety bubble up for the ceremonial pitch. (I saw that later; at the time I was listening on radio, and Howie Rose did a nice job discussing not only Pulse but also the work of Allan Lans as the Mets’ long-ago team psychiatrist.)

Pulsipher and Lans were pioneers of a sort; these days baseball specifically and all of us in general are wiser and kinder about acknowledging mental health issues and treating them as real things to be dealt with like any other injury, instead of dismissed as weaknesses or failures. Pulse threw out the first pitch; the Rockies’ Austin Gomber and Daniel Bard have been open about anxiety and seeking treatment. That’s progress, though more is needed — no family or circle of friends is untouched by mental health, and the sooner we remove the stigma from such discussions, the easier it will be for those we love to open up, reach out and get help.

And there’s another context for Bill Pulsipher: His June 17, 1995 debut was the first meeting for a pair of Mets fans who’d become friendly while working through their Met-related angst on an America Online message board. I’d just moved from Maryland to Brooklyn and the Mets’ prized prospect was coming up to the big leagues, so Greg and I made plans to meet at Shea. (Trivia time: In some alternate universe this blog is called Meet Me at Gate E.)

Pulse’s first pitch went to the backstop and he gave up five in the first as the Mets bowed to the not-yet-exiled Astros. Not exactly the starting point of a glittering career, but it did cement a friendship, which led, a decade later, to the blog you’re reading today.

by Greg Prince on 6 May 2023 10:43 am The primary bus scene in Bull Durham, the one in which wise, older Crash Davis informs young, wild Nuke LaLoosh that nobody gets woolly, rushed across the strike zone of the mind Friday morning, specifically the line, “You could be one of those guys.” One of the realest-life Nuke LaLooshes to have toed a rubber in the Show since the realest-seeming baseball movie ever made was released had just announced his retirement. That pitcher, the real one, was born slightly nine months after that film opened in theaters. It was as if Matt Harvey’s parents came home from the cinema and decided to create a baby toward whom the gods would reach down and turn his right arm into a thunderbolt.

Make no mistake about it: Matt Harvey was One of Those Guys. In the Show, nobody could hit Matt Harvey’s fastball. Nor could they touch his ungodly breaking stuff, let alone his exploding slider. That mastery and mystification of major league hitters didn’t last forever, but at its peak — a span measuring what felt like the greatest 27 days of our life, spread out roughly every five days over the course of one early April to one late August (26 in the regular season, one in an exhibition that lived up to its billing as the Midsummer Classic) — Citi Field was a cathedral. In 2013, now suddenly a full decade ago, anywhere Matt Harvey pitched approached holy site status.

There’d be more pitching beyond 2013, the year of Harvey Days. Some of it proved quite sublime. One night of it we either wish could have lasted a tad longer or, maybe, been cut off a batter or two before it went awry. Matt Harvey pitched us to the 2015 World Series. He had company and he had help, but it doesn’t feel wrong to credit Matt as the driving force. The World Series was a destination that was difficult to imagine in the summer of 2012 when the Mets were in the midst of a meandering bus trip to nowhere, but it may have begun to come ever so slightly into imagination’s view when the rookie righty made his major league debut in Arizona and blew Diamondback after Diamondback away.

The taste he gave us across ten starts in ’12 whetted our appetites for ’13. The Mets were still driving in circles in ’13, but you could begin to discern an off ramp. Just pull over to the right shoulder so we can get a sense of where we’re going. Y’know what, can we just let Matt drive us? We would, in fact, ride the homegrown highway of pitching to an October that suddenly burst onto our GPS. Matt Harvey was the first exit to a most rewarding trip. We’d pick up speed when we’d pick up other arms to aid and abet him, but the starting started with Harvey.

Those were the Harvey Days, my friend. Even with hindsight, we thought they’d never end.

There’s a statue of Tom Seaver outside Citi Field since 2022. There could have been a statue of Tom Seaver outside Citi Field since 2009. There could have been a statue of Tom Seaver outside Shea Stadium while Tom Seaver was pitching inside Shea Stadium. When you start talking Met starting pitchers, particularly righthanders who led the way to better days, you start with a high bar. Seaver wasn’t just One of Those Guys. He was the guy where we were concerned. Still is. After Seaver stopped pitching for us in 1983, only one righthander neared and occasionally cleared that bar: Dwight Gooden, who came along in 1984. Gooden had Friday nights in particular and a couple of years when every day he pitched was Friday night. If he didn’t maintain a Seaverian peak quite as long as Tom did, Doc’s right arm resided in the same league long enough. He was a Show unto himself.

Gooden’s last Met pitch was thrown in 1994. Doc wasn’t quite Doc by 1994, but you could watch him and remember. The Mets developed some quality righthanded pitchers over the quarter-century that followed Doc’s mid-’80s apex, but for the most part, they generated as much electricity as a hamster wheel. If you wanted to light up Shea, you signed a free agent like Pedro Martinez. Actually, there wasn’t anybody else like Pedro Martinez, and even the great Pedro could be fully like Pedro for not much more than a veritable blip once he accepted our friend invitation.

No, you want to develop your own righties. Lefties, too, but since Seaver, we’ve led with our right arms. It’s a Met thing. Or it was. From the denouement of Doc to the post-Pedro period, we came up with what righty starters from our minors? The cream of the crop included Bobby Jones, Jae Seo, Mike Pelfrey and Dillon Gee. Good guys, but none among them One of Those Guys. Paul Wilson could have been had injury not befallen him way too early. Jason Isringhausen sure looked like he was gonna be One of Those Guys, but injury rerouted him to relief and success elsewhere.

Matt Harvey comes up in 2012, two years after the Mets drafted him in the first round in 2010, and by 2013, there’s no doubt he’s One of Those Guys. Three more guys who you deem in the same vicinity as Matt follow in rapid succession: Zack Wheeler, Jacob deGrom and Noah Syndergaard. With a rotation like that, our bus could really start rolling. It’s not quite as neat as all that in practice, because by 2014, while Wheeler, plucked young from the Giants, is still learning command; and deGrom is convincing the brass he’s not here to merely soak up innings while Rafael Montero gets his big break; and ex-Jay farmhand Syndergaard wonders why nobody’s calling him in Las Vegas, Harvey is sidelined altogether, rehabbing from Tommy John surgery. That’s why 2013’s span of best days of our life ends in late August. The last time we see Matt is on a sunny, shadowy Saturday at Citi. He’s facing the Detroit Tigers. Max Scherzer is pitching for them. They’d both pitched in the All-Star Game in the same park the previous month. Everything is unprecedented about this matchup, especially how not quite right our righty looks on the hill. The Tigers, who are playoff-bound, keep hitting Matt. Matt scatters as many as he can, but something is off. It’s his elbow. It will need to be repaired.

We’d miss Harvey Day like a phantom limb in 2014. We’d get Matt back in 2015 and still talk up Harvey Day, and there’d be some splendid numbers and performances, but the One of Those Guys era ended that August afternoon in 2013. Matt could do no wrong to that moment. Or if he did wrong, we didn’t sweat it. He evoked Seaver and Gooden. They were our big three. A dominant righthander of our very own is what we came for roughly every generation. We had to skip a generation from the mid-1990s to the early 2010s. Harvey brought it back to us all at once.

Then the gods took it away from him and us, bit by bit. Again, heckuva year in ’15. Matt clinched the division title in Cincinnati. He settled down after a bumpy second inning to go five and notch the win the first time a postseason alighted at Citi Field, Game Three of the NLDS versus the Dodgers. He quashed the Cubs in the opener of the NLCS that followed. Of course he was given the honor of starting the World Series for the first Met pennant-winner in fifteen years. Of course he didn’t want to leave the last Met World Series game the Mets have played since then, eight years ago, when he’d shut out the Royals for eight innings. Terry Collins had a different idea. Matt Harvey changed his manager’s mind.

He couldn’t change history, though. You thought he might. He’d been One of Those Guys so effectively that you wanted to see him do it a little more. He couldn’t. He never would again. Damn.

Matt Harvey’s Met career ended in the bullpen in May of 2018, and not as a reborn closer. He was excess pitching inventory at the unseemly end. It had been over between him and us for going on three seasons. None of really wanted to admit it. Matt’s big league career continued a few more years with a few other teams. He last pitched in the majors in 2021. It’s 2023, the year Matt Harvey, 34, announced his retirement. He’d been through a lot. He gave us his best. His best was frigging phenomenal. We should remember that.

In the first game the Mets played after Harvey confirmed he was done, the Mets looked alive. A righthander pitched. This righty, a rookie (but not really), doesn’t mind flashing a logo advertising a personal brand on his gear. In Kodai Senga’s case, it’s a ghost, for his signature pitch the ghost fork. It’s all in good fun. The Dark Knight imagery Matt took up was fun for a spell, too. The Mets very much needed an outstanding start from Senga after Scherzer imploded on Wednesday night and Justin Verlander needed an inning to get right on Thursday afternoon. The Mets had lost four in a row. Kodai wasn’t imported from Japan to be the stopper, but on Friday night at Citi Field, he had to be at least an approximation of One of Those Guys.

And he was. Senga went six innings and permitted no runs. Walked four, but no base on balls became a Rockie run, so no problem. Kodai gave up only two hits and had all his pitches, not just the animated one, working. Like many of the fine righties who have preceded him as Met starters, Senga went largely unsupported by his offense. But not wholly unsupported, as Brandon Nimmo, the goat rather than GOAT of Thursday’s ninth inning, went deep in the fourth inning to provide his pitcher a 1-0 lead. Nobody else in the Met lineup did anything nearly as useful, but that’s why you pay for pitching. No runs given up by Senga over six; no runs given up by Drew Smith in the seventh, David Robertson in the eighth or Adam Ottavino in the ninth. Colorado seemed poised to close in those last couple of innings, but our bullpen corps stiffened. I was a little worried when I saw 2015 Royal Mike Moustakas come out to pinch-hit for the Rockies. Moustakas was the batter coming to the plate when Collins finally pulled Harvey from the mound in Game Five. The 2-0 lead had been trimmed to 2-1. Versus Jeurys Familia, Moustakas grounded to first, advancing Eric Hosmer to third. A blink later, it would be 2-2. Matt Harvey, who’d striven to the point of resistance of authority to complete a World Series shutout, got a no-decision.

Back in the present, Moustakas struck out versus Ottavino for the second, unproductive out of the ninth, and Charlie Blackmon lined to Starling Marte to end the game with the potential tying run on third. Four Mets pitchers had shut out the Rockies, 1-0. I shunted aside the regret-laden memory of Moustakas and Hosmer and all those dratted Royals and replaced it with the recollection that I was in the park to watch Matt Harvey shut out Colorado all by himself on one of those Harvey Days in 2013. It was the first shutout of our ace’s career. Blackmon singled with two out in the ninth that August night for the Rockies, but the 24-year-old Met righty popped up Troy Tulowitzki to successfully finish what he’d so brilliantly started. We didn’t know it at the time, but it was Harvey’s final win of 2013. We also didn’t know and couldn’t have guessed it would turn out to be the only shutout of Matt’s career, postseason included.

We expected more, but it was just one of those things.

National League Town licked its wounds after a band of Tigers scratched and clawed the Mets. Listen to what that sounds like here.

by Jason Fry on 4 May 2023 10:17 pm I know nobody wants to hear it, but Justin Verlander didn’t pitch that badly.

Even I don’t particularly want to hear it. I’m up in New England, running around doing nonsense, and so on Thursday afternoon I got MLB At Bat fired up a little late and this was more or less my reaction: Waitaminute, 2-0 already? Back-to-back homers? Ya gotta be kidding me.

I was stewing. You were stewing. Verlander, one presumes, was stewing. (Hey, at least I got to recap a game — my last three had been rained out, which I’m pretty sure is a Faith & Fear record.)

Nothing bad happened after that — in fact, a lot of good happened, and you don’t even need to squint to see it that way. Verlander was throwing 95/96, unlike his fellow former Tiger Max Scherzer, now officially the subject of worries. He worked out of a couple of jams by throwing hard and throwing smart in equal measure. He seemed physically sound. All to the good, particularly given the perilous state of the Mets’ rotation.

What wasn’t good was that the Mets were all but helpless against Eduardo Rodriguez — I’d make a cheap “who the heck is Eduardo Rodriguez?” crack except off the top of my head my list of Tigers would be a) Javier Baez, from whose bat an excess was heard this week; b) the decaying corpse of Miguel Cabrera; and c) uhhhhh. Well, the jokes on us — that collection of no-names just swept the Mets behind a comeback, a bludgeoning and a tight game that never felt tight. On Thursday the Mets never had a runner reach second — Tommy Pham and Brandon Nimmo were thrown out attempting to achieve this modest feat, with Nimmo’s erasure coming, for some unfathomable reason, in the ninth with Starling Marte as the tying run. (Buck Showalter likened the decision to a guy trying to make a 30-foot jumper, and I can’t improve on that.)

The Mets are now 16-16, and their mediocrity understates what a confounding season it’s been. The team either looks unbeatable or inept, with little in between, and the best description of that I can think of is “exhausting.”

There’s hope, of course — only the terminally cynical or conspicuously unserious write off a team before Mother’s Day — but at least for me, even that hope comes with a side of disgruntlement. The Mets’ biggest reason for hope is of course the fact that there are now 22* wild cards in addition to playoff spots obtained more or less honestly, which means all manner of flawed teams will make the playoffs and then hope, perfectly reasonably, to ride a handful of small-sample-size coin flips to a title.

We’re a flawed team, but probably not one so flawed it can’t clear that middling bar. The question that’s creeped into my head of late, whispering in a voice I don’t like but haven’t been able to silence, is how much of an accomplishment that actually is.

* This number may be incorrect, but ask me if I give a fuck.

by Greg Prince on 4 May 2023 11:38 am The Wednesday morning news where Detroit was concerned was good. The Spinners, the enduring, melodious R&B group out of Ferndale, Mich., had made it at last to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Their most fervent fans — a cohort that surely includes me — had been waiting what felt like forever to hear they had been chosen. Imagine how long “like forever” that felt to Henry Fambrough, the last surviving founding member of an outfit whose roots date to the 1950s. Fambrough is about to turn 85 and only recently retired from performing. He’s been out there, on the road, with dedicated, talented successors to the late Billy Henderson, Pervis Jackson, Bobby Smith and Philippé “Soul” Wynne. Those five legends will be inducted by the Hall as the classic lineup from the heart of the 1970s (“I’ll Be Around” to “Rubberband Man”), but props are also in order for John Edwards, who succeeded Wynne when Wynne left for a solo career, and G.C. Cameron, who Wynne had succeeded.

Wynne, de facto front man for the quintet during its prime, joined the group as the Spinners were about to achieve their trademark success under the guidance of producer Thom Bell at Atlantic Records, but it is Cameron’s voice you hear most prominently on their first true pop hit, the pre-Atlantic “It’s A Shame” from 1970. The real shame is that it took the Spinners as long as it did to score that radio breakthrough, given that they were signed to a label otherwise known for launching superstar acts.

The Spinners were on Motown. Usually when Motown is invoked, America feels a warm glow reflecting on all those fantastic vocal groups it gave us. And why shouldn’t we? The Supremes. The Four Tops. The Temptations. The Miracles. The Jackson 5. (Not to mention solo acts like Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder.) Somewhere down the deepest roster music may have ever known, never getting much of a chance to show their stuff while Berry Gordy was turning Motown HQ into Hitsville U.S.A., were the guys from Ferndale. They were not a priority. In short, Motown didn’t know what to do with the Spinners. They had to leave Detroit to reach the big time — if they weren’t Motown’s Nolan Ryan, they were at least their Amos Otis. The Spinners, from right there in Michigan, would become known as the leading practitioners of Philly Soul. “It’s A Shame” amounts to a footnote in the hallowed label’s discography.

The Spinners, while still at Motown. Like the Mets, they didn’t really score enough in Detroit. Hence, when Motown is invoked, my warm glow is tempered by a bittersweet chill. You had the Spinners, you all but ignored them for the better part of a decade, you let them get away. Fambrough had to wait until his mid-eighties to be told his music qualified as immortal? He had practice waiting. Motown made his group cool its heels, standing in the shadows of everybody else. I was elated and emotional when I learned the Spinners were going into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame on Wednesday morning, but, as with the family of Gil Hodges having to absorb election after election of disappointment before he finally got into baseball’s Hall, I found it hard to forget that so much for the Spinners could have come sooner.

***The concept of a wasted opportunity in Detroit was therefore top of mind come Wednesday afternoon and Wednesday evening. A visit to Comerica Park, coupled as a day-night doubleheader after rain on Tuesday, theoretically provided a better-than-even chance to pile up wins. The Tigers entered this series 10-17 and in the midst of essentially a seven-year losing streak. Every day, however, is a new day. With two chances to win, the Mets went back to their hotel with a pair of losses.

It’s a shame, indeed.

The lightly attended day portion was the shamier half of the festivities. The Mets seemed to have handle on that one, leading, 5-4, after falling behind early. Joey Lucchessi had straightened out after gophers got loose on his ledger. Eric Haase bit him for a three-run homer in the first and Old Friend™ Javy Baez led off the fourth to nip him again. With five more frames scheduled plus nine come nighttime, Joey the Churve could have continued to chomp up innings, but Buck Showalter removed him because he might need him Sunday against the Rockies…which is what Met starting pitching has come to, treating Lucchesi four days in advance like he’s Randy Johnson in Game Six of the World Series, coming out with a big lead after seven because he might be needed the next night to close out a dynasty.

Say goodbye to Joey the Churve, say hello to Jimmy the Yak, and Jimmy the Yak — Jimmy Yacabonis on your scorecard — was a beast: nine Tigers were claws poised to do damage; nine Tigers tiptoed to their dugout ready for a mid-afternoon nap. Maybe you could have your Churve and eat it, too. The Yak made Buck look like a bigger genius than Bob Melvin removing the Big Unit 22 years ago. It helped that in the half-inning interval between Lucchesi and Yacabonis, the Mets had wrestled the lead from the Tigers, boosted by Francisco Lindor’s fifth homer of the season and the Mets’ third of the day. Tommy Pham and Mark Canha had previously gone deep in a ballpark previously known as stingy for allowing home runs. Bring in the fences and watch the balls fly out.

The Mets’ penchant for assuring they wouldn’t be swept in a doubleheader got pinched in the eighth. Adam Ottavino, perhaps rusty from not pitching much since going on paternity leave or sleepy from having become a new father, was not sharp. He gave up a single and a steal to Matt Vierling; hit Baez; allowed both runners to move up on a groundout; and succumbed to the newest Metkiller to haunt our dreams, Haase, he who knocked in each of his teammates from whence they stood on base. Suddenly, the Tigers were ahead, 6-5. Alex Lange came on to save it and was successful.

If the Mets wanted to maintain their freakish string of going no worse than 1-1 on days with two games, they’d have to take the nightcap. Good thing they had Max Scherzer returning to the mound…is what you might have said before Scherzer actually pitched. The legendary former Tiger ace (we have a couple of those) was rustier and flatter than Ottavino. Max hadn’t pitched since his suspension for sweat and rosin nearly two weeks before, and before that, he had been sidelined by back issues. So maybe that’s it. Let’s say that’s it. To say worse — like at 38 and in a sped-up world of pitch timers, the aging Max is not physically equipped nor mentally prepared to grapple with the current state of baseball — is just too depressing. Haase homered again. Vierling homered. Max gave up six runs, all earned, in three-and-a-third.

The Mets didn’t do much to Tiger starter Michael Lorenzen. We got one run, driven in by Daniel Vogelbach, the designated hitter. Maybe if they designated every Met a hitter, our hitters would better understand the nature of what to do while attempting to hit. Lefty reliever Zach Muckenhirn made his debut for us, and it didn’t go badly. Muckenhirn is the 1,197th Met overall and, barring who knows what before today’s first inning, will always have the pleasure of knowing he will always sit directly above prospective Met No. 1,198 Justin Verlander on the franchise’s all-time chronological roster. Jose Butto also successfully soaked up excess batters, which is all one can ask of a person announced in advance as the 27th man in an endeavor that usually encompasses 26 men. “Hey, Lastie, they’re puttin’ ya in!”

But, alas, not Splitsville. The final in the second game was Tigers 8 Mets 1, snapping that streak of not getting swept in doubleheaders at 25, a feat that should sound more impressive than it does. Knowing that a bunch of those doubleheaders date to 2021 — when doubleheader games went seven, and “extra” innings meant you might have won in eight, and any game that went extras was further besmirched by the presence of the automatic runner — detracted from an overwhelming sense of accomplishment. Also knowing that the last doubleheader sweep against the Mets happened in 2020 makes me think none of it was quite authentic, given that the seven-inning doubleheader rule was implemented then and there were bleeping cardboard cutouts in the stands, with even fewer people on hand than there were for the Mets-Tigers makeup opener. If we’d done nothing but sweep doubleheaders for two years, I might feel differently. Of course, I’d have taken one win out of two on Wednesday at Comerica versus what actually happened.

No trip to Splitsville on this stop in Hitsville. Yes, it’s a shame.

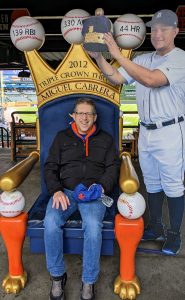

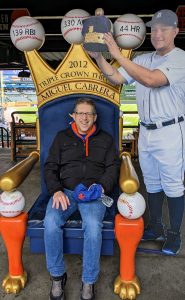

***Another shame would be if Mets fans, even if it’s only on television, don’t get one more look at Miguel Cabrera in Thursday’s finale. How often do you get to see a member of the 3,000 Hit Club in action, even if it’s halting action, even if it’s as a DH? Twenty such members have gotten at least one of their 3,000 or more hits against the Mets, even if they weren’t members of the 3,000 Hit Club most of their plate appearances against us (because it takes a long time for even the greats of the game to make it 3,000). Plus, Cabrera, 40, has 99 hits versus the Mets in his career, most of them accumulated before he was an icon and merely a Marlin. Even with that Fish story in his background, I’d rest more easily knowing Miggy at least got a shot at a hundredth.

From 2003 to 2007, we knew he was good, but he wasn’t yet exalted. He had to become a Tiger to become a legend, alongside Scherzer and Verlander. Man, those Tigers were good. I’d be fine if they could hold off on being successful for one more day, but if it doesn’t make a great deal of difference to the Mets getting back on track, I’d really like to see Cabrera not only bat this afternoon but maybe single with nobody on and the Mets up by a lot.

Miguel joined the 3,000 Hit Club on April 23, 2022. Mets pitchers began contributing to his climb up that golden ladder on June 24, 2003, when Al Leiter gave up a leadoff single to Florida’s recently promoted eighth-place hitter at Shea Stadium on June 24, 2003. Leiter began pitching in the majors in 1987. Cabrera is still playing in the majors in 2023. That’s a 36-year span, overlapping a bit (Leiter and Cabrera would be teammates in 2005). It was the Marlin rookie left fielder’s fourth hit as a big leaguer. The Marlins went on to win that game, 8-4. They also went on to win the World Series, fueled in great part by their 20-year-old callup. Miguel wouldn’t be a left fielder or bat low in anybody’s order for long.

The last time we had the pleasure of Cabrera’s company at Shea was September 30, 2007. We weren’t too terribly focused on Miguel the cleanup hitter that Sunday afternoon save for his singling in the first run of the top of the first inning. Before we got to the bottom of the first inning, it was Marlins 7 Mets coming to bat/going to hell. After five years and 36 hits at our playpen of then 44 years, Cabrera was traded to Detroit, one of those many, many moves the Marlins made to make sure they’d escape competitive viability for as long as they could.

With the Tigers, Cabrera could be paid like the superstar he had become. We wouldn’t see him very often from the last Shea year of 2008 onward. That wasn’t so bad from a not contributing to our downfall on the last day of seasons as a Marlin aspect. It’s a little disappointing in that here was this great hitter mostly out of our view. This isn’t an endorsement of Interleague play. It’s “phooey” on the Marlins for being run like the Marlins. As he grew toward immortality in Detroit, Miguel swung by Citi Field for three series. He liked it more than Shea. Whereas he batted only .240 in Flushing from 2003 to 2007, he murdered Met pitching in 2010, 2013 and 2019, racking up an average of .424, with 14 of the hits that have, to date, added up to 3,098 in all. The last one was on May 25, 2019, a single to get the top of the twelfth going off Hector Santiago. The single, No. 2,730 for his career, didn’t drive in a runner from second because in 2019, they didn’t start extra innings with a runner on second. After Santiago walked the next batter, Tigers manager (and Old Friend™ Ron Gardenhire) pinch-ran for Cabrera, and that was the last we would see of Miggy in Queens.

The Tigers will have a hard time filling Cabrera’s throne. The hit in top of the first inning on 9/30/2007 may have been the most damaging (as was every Marlin hit in the top of first inning on 9/30/2007), but the one I’ll remember Cabrera delivering against the Mets most came the last time I saw him, on Sunday, August 25, 2013. It was a first-inning homer to deep left off Dillon Gee that could have ordered brunch, because it rushed into the Acela Club like it had reserved a table. Miggy would garner three hits that matinee, the third of them in the ninth. The Tigers led the Mets, 4-3, going to the ninth. The Mets wound up losing, 11-3, after the ninth. It was one of those innings on one of those days in one of those years. Had we had to have kept facing Cabrera nineteen games annually, there likely would have been more of those innings and those days and maybe more of those years.

Nevertheless, you don’t hide from competition. We are better off as fans facing legends in the making, legends in their prime, legends on the wane. If Cabrera does play and get a hit in his Met finale, he will have not only exactly 100 hits against us, but 50 in our parks, 50 in his. That’s evocative of the career of the first member of the 3,000 Hit Club to take on the Mets, Stan Musial. Musial’s hit total against everybody (not just us) was 3,630: 1,815 in St. Louis, 1,815 on the road. Musial got us for 32 hits in all, but none before en route to 3,000, given that Stan the Man ascended to that plateau on May 13, 1958, and the Mets didn’t exist until April 11, 1962. That was when Musial logged his first hit against Met pitching. It came in the very first inning of our very first game, driving in the very first run any Met pitcher (Roger Craig) ever surrendered. Musial’s all-time hit total rose to 3,402 with that knock.

Conversely, Cabrera hasn’t had a hit off the Mets since getting his 3,000th. He hasn’t played against them. Dave Winfield, Eddie Murray, Wade Boggs, Rickey Henderson, Rafael Palmeiro and Alex Rodriguez never added to their post-3KH sum against the Mets, either, usually because they and we ceased crossing paths late in their runs toward (if not to) Cooperstown. Roberto Clemente, sadly, never had the opportunity to hit against us post-3,000, dying after notching No. 3,000 against the Mets at the end of the 1972 season off Jon Matlack. That went into the books as a milestone double when it was recorded. It became his final hit when he died in a plane crash on his humanitarian mission to aid victims of the Nicaragua earthquake three months later.

The player with the most hits against the Mets after collecting his 3,000th is also the player with the most hits, period: Pete Rose (though Rose is second to Lou Brock among 3,000 Hit Club members in terms of total career hits versus the Mets prior to 3,000, with Lou leading in the pre-3K segment, 289 to 257). Pete, a Phillie from 1979 through 1983 and an Expo for the bulk of 1984, played us a lot after securing his 3,000 hit on May 5, 1978. He hit us a lot, too, the last time at Riverfront Stadium, on July 22, 1986, the fourteen-inning affair that is best remembered for about five other things, all of them somehow more memorable than the last hit the Hit King ever got off a Met pitcher.

It was in the tenth inning.

The game was in the tenth because Dave Parker dropped a sure third out in the ninth.

Rose, as Reds player-manager, had Eric Davis pinch-run for him, but Davis soon had to be pinch-run for by pitcher Tom Browning because Davis was ejected in a brawl with Ray Knight that also saw Knight and Kevin Mitchell thrown out.

Rose’s hit, the one that created the baserunning opportunity for Davis to slide a little too hard into Knight and therefore instigating the melee, was off Jesse Orosco, who would be playing right field by inning’s end, not as punishment for permitting a hit to 45-year-old player-manager Rose, but because of the fight — not only was Mitchell ejected, but so was Darryl Strawberry (though that happened earlier), and Davey Johnson was low on bodies.

Rose was back in managerial mode again soon enough, spotted by a Channel 9 camera combing the pages of a rule book in the dugout to check if Orosco taking warmup pitches after coming back in from the outfield to pitch was legal; Jesse and Roger McDowell switched off with one another at the behest of our personnel-strapped Davey skipper…when one or the other wasn’t switching off with Mookie Wilson between left and right fields, depending on who was batting for Cincy.

Also, with Knight tossed, Gary Carter played third, and Kid helped execute a massive 3-5-4 DP started brilliantly by Keith Hernandez.

And, almost incidentally, Howard Johnson, by then the shortstop, blasted a three-run homer in the fourteenth to ultimately win the game, 6-3.

So you can see why Pete Rose’s last hit ever against the Mets, the 4,247th of a 4,256-hit career, kind of got lost in the shuffle that night in Cincinnati.

This afternoon in Detroit. Miguel Cabrera, playing out his twenty-first and final season, is not in the starting lineup. It’s our last chance to see him play our team. Maybe he’ll pinch-hit. Maybe he’ll get a hit. Maybe I’ll slightly applaud if the hit doesn’t hurt us on the scoreboard. It never hurts to appreciate greatness before it exits the stage altogether.

MOST HITS AGAINST THE METS FOLLOWING A CAREER 3,000TH HIT

Pete Rose 139

Hank Aaron 46

Stan Musial 32

Willie Mays 16

Ichiro Suzuki 11

Derek Jeter 9

Tony Gwynn 8

Craig Biggio 5

Cal Ripken 4

Lou Brock 3

Adrian Beltre 3

Albert Pujols 3

Miguel Cabrera TBD

Photos courtesy of Long Island’s Own Jeff Hysen.

by Greg Prince on 2 May 2023 10:47 am Everything one needed to know about Mets-Braves games seemed to be on display in the bottom of the first inning of Monday afternoon’s doubleheader opener at Citi Field. We reached the part where the heartaches come pretty early. Atlanta was already ahead, 3-0, with the Braves’ additional top-flight catcher Sean Murphy — because harboring a vengeful Travis d’Arnaud wasn’t enough — having taken Mets starter Denyi Reyes deep in the top of the frame. While you are checking your depth chart to see where Denyi Reyes slotted in among the list of the many, many pitchers the Mets projected as possible starters in 2023 (nowhere), and then calculating how long it took for them to assign fringe middle reliever Reyes a start nonetheless (the season’s fifth week), I will recount the half-inning that encompassed everything one needed to know about Mets-Braves games.

• There was a triple that almost went over the fence, but didn’t.

• There was a single that almost skipped by the right fielder for a double, but didn’t.

• There was a stolen base on a throw that almost went through to center, but didn’t.

• There were bases loaded with runners threatening to become runs, but didn’t.

The half-inning that started Braves 3 Mets coming to bat ended Braves 3 Mets 1, because even the Mets at their most futile, which is to say when facing the Braves, couldn’t come away totally empty-handed after Brandon Nimmo’s leadoff triple, Starling Marte’s walk, Francisco Lindor’s single, Francisco Lindor’s stolen base and Daniel Vogelbach’s walk all occurred before a third out. No, we got that much out of the home first.

Nimmo was not stranded at third after his shot to right just missed clearing the orange line. To my way of thinking, I wasn’t even sorry it wasn’t a home run. A solo dinger is a run, and the Mets hadn’t done much with first innings and runs lately, but then the bases are bare and the opposing starter’s slate is newly clean. This, a runner on third with nobody out, somehow shaped up as more promising. Brandon’s ninety feet from scoring, and the pressure begins to mount on Spencer Strider. Strider indeed walks Marte, and we’ve got something cooking. Sure enough, Lindor hits one to right to bring in Nimmo, and…

That’s where it begins to get a little too Mets-Braves up in here. Ronald Acuña, Jr., snatches Lindor’s ball before it can get by him, which keeps Marte from going farther than third and doesn’t let Lindor make it to second. It looked like it would bounce to the wall, but there’s Acuña with a backhanded stab that keeps Met runners where they can do minimal harm.

We didn’t know that would amount to “none” yet, but it did. After Pete Alonso struck out and while Jeff McNeil batted, Lindor was determined to get that extra base, taking off from first to steal it. One bag on a stolen base attempt is almost a given these days, and Francisco had no problem making it in safely. The bonus was going to be Murphy’s throw scooting past second base, allowing Starling to trot in with the Mets’ second run, except shortstop Vaughn Grissom did his own grabbing and improbably plucked the ball from its path toward the outfield. Marte could not advance. Lindor could not advance. McNeil could not get them home or get on himself, popping up. Vogelbach walked to maintain pressure on the struggling Strider. Brett Baty presented one more obstacle to the Braves’ starter, but not an immovable object. Brett struck out with the bases loaded.

I’d like to say I didn’t know the game was lost at 3-1, but that was just too many almosts for one half-inning when the opponent is the Braves. Maybe it would have been too many almosts for one half-inning when the opponent is anybody, but the Braves have been the Braves too much and too long, especially too recently, where the Mets are concerned. Almost-ing them isn’t gonna cut it, especially when they’re being definitive about increasing their lead off Mets starter Denyi Reyes.

Reyes gives up a single to Michael Harris II and a homer to Kevin Pillar. Reyes is replaced by Syracuse recallee John Curtiss. Curtiss gives up a homer to Acuña. Instead of cutting into the Braves’ edge further or tying them or passing them, we fall further behind them. Arithmetically, allowing three hitters to become three runners who cross the plate can equal no more than three runs. It felt like more. First, those two instant runs brought in by Pillar, whose last notable act as a Met was getting caught up in the fun and excitement of the thumbs-down kerfuffle of late 2021. Of course, we didn’t have time to snarl at Pillar for pulling a d’Arnaud on us because in a matter of seconds, our attention was turned to Acuña lofting a fly ball to where only the likes of Boeings, pigeons and Cespedii have previously dared to soar. Ronald the Junior placed a Curtiss pitch up in the Promenade boxes, about as high up as Yoenis — a neon ghost we can’t see — scaled in 2016, except not pulled toward the corner, thus making it visually more impressive. Aaron Judge also traveled up to those distant precincts in 2017, but why drag him and his team into this when he have Atlanta and Acuña to provide ample angst?

However and wherever the combined force of the three runs in the top of the first; the bases left loaded in the bottom of the first; and the three runs whacked home in the top of the second landed psychically, it was only 6-1, Braves, mathematically. “Only” seems a silly modifier here, because many opportunities for Atlanta havoc remained and did I mention our starting pitcher had been Denyi Reyes? And our next man up was John Curtiss? And a torrent of better options implicitly eluded Buck Showalter? But unless there’s lots of rain in the forecast, seven-and-a-half innings still awaited. Yes, the Braves could go to town so much in that time that they’d be enjoying dumplings on Main Street, but the Mets were welcome to try their luck in Flushing, too.

Lucky would not describe how Game One turned out, but the Mets at least honored the possibilities inherent in a nine-inning affair. Alonso erased the memory of his first-inning strikeout with a three-run homer in the fourth. It’s not 6-1 anymore. It’s 6-4. Baty not coming through with the bases loaded in the first did not preclude him from leading off with a home run in the sixth, the young lefty swinger besting lefty reliever Dylan Lee, marking another peg up the ladder for a kid on the rise. Ohmigod, it’s suddenly 6-5. Strider didn’t absolutely choke off the Mets; he lasted only five. Though Reyes imploded and Curtiss was greeted rudely, Stephen Nogosek’s return from the IL wilderness went swimmingly for two-and-two-thirds, and by the bottom of the sixth, the opener wasn’t shut.

By the top of the seventh, it was back to being a rout, with Jeff Brigham pitching and that man again, Murphy, producing yet another three-run homer. Nine to five, what a way to lose a ballgame. Except shaky Brave pitching (a pair of HBPs from Old Friend™ Collin McHugh) and shaky Brave fielding (a wild Grissom throw on what should have been an inning-ending DP) in the seventh permitted two runs to close the gap to 9-7. Tommy Hunter’s two scoreless innings maintained the concept of conceiving a desirable outcome conceivable. Ya gotta conceive! One more scintilla of hope arose in the bottom of the ninth when the erstwhile everyday entrant Eduardo Escobar emerged from the dugout to pinch-hit the homer that made a bad loss verge on agonizing. They didn’t quit. They kept coming. But they never came all the way back. Comebacks of that nature generally appear only in a paperback novel, the kind that drugstores sell. Yeah, that’s agonizing.

No time for agony, however. Braves 9 Mets 8 was forty minutes from Braves coming to bat in the top of the first, the Mets taking the field, the enormous scoreboard reverting to blank. Another chance is the beauty of a doubleheader. The likelihood that the Mets will have something to show by the end of it is even more beautiful. The Mets entered Monday not having been swept in a twinbill since cardboard cutouts sat in for spectators during 2020; not having been swept in a twinbill with people in the stands since 2017; not having been swept in a single-admission twinbill with people in the stands since 2016; and not having been swept in a single-admission twinbill with people in the stands at Citi Field since 2012. If you were ever tempted to respond to one of those come-ons daring you to bet responsibly, the Mets winning the second game Monday was as close to a sure thing as existed.

Now, you know there are no sure things in baseball. You might believe the Braves sticking it to the Mets is a sure thing, but look!

There’s Tylor Megill, an actual Mets starting pitcher pitching, and he’s not giving anything up, save for a leadoff hit-by-pitch to Acuña’s left shoulder that conveniently sidelines him for the rest of Game Two. (If you could read my mind, you’d have a hard time searching out my empathy, provided the guy didn’t actually sustain more than a bruise.)

There’s Vogey doubling in a second-inning run off ancient Charlie Morton; he’s been pitching since Shea Stadium stood.

There’s Marte with a single to bring home Baty, who had doubled, in the fifth.

There’s Megill in a spot of trouble in the sixth, bases loaded, two out. If he can get out Eddie Rosario…no, that’s not gonna happen. Rosario doubles to score the first two runners, but at least we got that darn Sean Murphy at the plate.

What’s that?

Replay review?

We didn’t get Murphy?

Of course we didn’t.

Your sure thing is in peril with two on (Morton walked a pair) and two out (Michael Tonkin is on) and Francisco Alvarez up. Alvarez has been looking a little more certain of himself every day. The last time there’d been a baseball game in New York, before the weekend turned all New Yorkers into rainy day people, Alvarez stroked a sweet fifth/last-inning single off the otherwise untouchable Max Fried on Friday night. Maybe because there were no Mets playing no Braves Saturday and Sunday, I read a surfeit into that most recent sample of Francisco’s advancement. As with Baty, you could convince yourself something was happening here. In the home sixth of Game Two on Monday, what it was was exactly clear: a strong double to left that scored both Met baserunners and gave the Mets back their lead at 4-3. McNeil would homer in the eighth to make it 5-3, and David Robertson would save it in the eighth and the ninth to keep it 5-3. You could officially cash in your winning splitting ticket. But remember to bet responsibly.

Not a great Monday for the Mets, as they did lose to the Braves. But not a great Monday for the Braves, as they did lose to the Mets. When you recall how badly Monday started for the Mets, nobody being completely satisfied come sundown rates as a sufficiently happy ending for us.

by Greg Prince on 29 April 2023 12:45 pm It’s not every day your favorite Major League Baseball franchise registers its 5,000th regular-season loss. The day our favorite Major League Baseball franchise registered its 5,000th regular-season loss, the skies clouded up all morning and afternoon; began to mist and drizzle as evening set in; and then began to pour down through the night. Somewhere between the drizzling and the pouring, and ahead of Saturday’s rainout, there was just enough time to get in that 5,000th loss.

The Mets played five innings of losing baseball on Friday night. Well, four innings of tying baseball and one inning of losing baseball. It’s a ratio that doesn’t look so bad until you remember how definitive one losing inning versus none involving winning can be. In this case, after David Peterson and Max Fried each put up zeroes for four innings, Peterson cracked. He almost held it together. Got one out in the fifth. Was on the verge of withstanding a single from Eddie Rosario and a double from Old Friend™ Kevin Pillar when he induced Michael Harris II (how nice knowing there are multiples of young Braves) to bounce to Brett Baty. Baty in the rain stood and thought about what to do with the presumably wet baseball for a spell, but ultimately and wisely gripped and threw it home to Francisco Alvarez. Alvarez didn’t have to tag Rosario, given that Rosario veered from the basepath toward Astoria, which even a bleeping Brave can’t get away with.

With two out, Pillar on third and Harris having moved up to second while Baty took his time throwing home, all Peterson, who had appeared sharper than he had the rest of April, had to do was take care of Ronald Acuña, Jr. The Mets haven’t yet figured out the best way take care of Acuña is to deny him entry to Citi Field. A solid single brought disgraced Bench Mobster Pillar home with the first run and pushed Harris to third. Really, it didn’t matter where Harris was pushed. He and Acuña would be powered across the plate by the next batter, Matt Olson. Olson rudely directed a baseball into those pavilion seats in front of Shea Bridge.

It was 4-0 and raining. You hoped both conditions would be temporary. You knew permanence loomed because of the ancient rule that says five innings can be an official game if the skies are angry enough to lop off the forthcoming four. The Mets could have scored four or five in the bottom of the fifth to forestall permanence let alone defeat in their role as the home team potentially leading at the end of five soaking innings, but that’s Max Fried out there on the mound. As long as he didn’t slip, fall and not get up, he was gonna take care of the Mets as seems to be his wont. Max Fried’s ERA in 2023 is 0.45. It’s not just us.

Max got through the fifth with minimal fuss. The rain fell with maximum impact. The tarp covered the diamond. I flipped to the Islanders ending their season in overtime. Somewhere along the way I remembered to check back in on the rain delay. It became a rain-shortened final of 4-0. The Mets’ season didn’t end. It didn’t continue strongly, but, we’ll continue to tell ourselves, it was just one game.

***The Mets have now lost 5,000 just one games. We didn’t bury the historical lede, so let’s exhume it before the rain stops and, sooner or later, we experience our 5,001st. It’s inevitable. You lose some, you win some. We just happen to root for a team that’s lost a bunch more than it’s won since its birth.

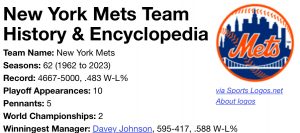

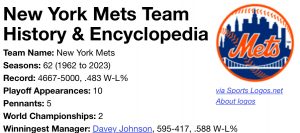

When Fried and Pillar and Acuña and Olson and the rain conspired to defeat the Mets, it knocked us 333 games below .500. Not for this year, but for all years. Our current lifetime record of 4,667-5,000 —— plus 8 ties — carries a lifetime winning percentage of .483. For context, if you apply .483 to a 162-game season, you’d have a team that goes roughly 78-84 every year for nearly 60 seasons. The Mets are in their 62nd season, but a few of them have been shortened by strikes and pandemics and whatnot. The Mets have never posted a 78-84 record at year’s end. The closest they’ve come is 77-85 in 2011, 2018 and 2021; 77-84 in 1991; and 79-83 in 2010 and 2014.

We got to L5K, and it didn’t even take nine innings. If you remember any of those six seasons, that, on average, is what our entire life as Mets fans has been. Of course we don’t take average into account over the long haul. Extremes make for punchier examples, and we’ve sure taken our punches since coming into this world. You know, if not by heart then in your gut, that we lost our first nine games to begin life, and 120 of our first 160. The losing continued at a slightly less self-defeating pace for the next five or so years. After dropping a Sunday doubleheader at Shea to the Cardinals on June 2, 1968, the Mets’ lifetime record was 341-675.

The Mets were off that Monday. Tuesday they played in Chicago. Jerry Koosman shut out the Cubs, 5-0. From that day forward through Friday night — June 4, 1968, all the way to that tarp staying put on April 28, 2023 — the Mets’ record has been 4,326-4,325. For nearly 55 years, the largest friendly sample size we can cobble, the Mets have been a winning baseball team. Not enough peaks and far too many valleys for our taste, but cumulatively, the past 8,651 Mets games played to a non-tying conclusion have indicated we root for a team you can’t, on average, call a loser.

Even if that’s a soggy hook on which to hang one’s hat after five innings drenched by Max Fried.

***The Mets’ lifetime record versus the Braves, both the Milwaukee and Atlanta versions, is now 411-496, meaning nearly every tenth Mets loss is a loss to the team we’ve considered our archrival for a couple of swaths of our history. Ever since Atlanta became a powerhouse and concomitant bane of our existence in the 1990s, we might have wondered what we ever did to make them this mad.