The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 2 May 2023 10:47 am Everything one needed to know about Mets-Braves games seemed to be on display in the bottom of the first inning of Monday afternoon’s doubleheader opener at Citi Field. We reached the part where the heartaches come pretty early. Atlanta was already ahead, 3-0, with the Braves’ additional top-flight catcher Sean Murphy — because harboring a vengeful Travis d’Arnaud wasn’t enough — having taken Mets starter Denyi Reyes deep in the top of the frame. While you are checking your depth chart to see where Denyi Reyes slotted in among the list of the many, many pitchers the Mets projected as possible starters in 2023 (nowhere), and then calculating how long it took for them to assign fringe middle reliever Reyes a start nonetheless (the season’s fifth week), I will recount the half-inning that encompassed everything one needed to know about Mets-Braves games.

• There was a triple that almost went over the fence, but didn’t.

• There was a single that almost skipped by the right fielder for a double, but didn’t.

• There was a stolen base on a throw that almost went through to center, but didn’t.

• There were bases loaded with runners threatening to become runs, but didn’t.

The half-inning that started Braves 3 Mets coming to bat ended Braves 3 Mets 1, because even the Mets at their most futile, which is to say when facing the Braves, couldn’t come away totally empty-handed after Brandon Nimmo’s leadoff triple, Starling Marte’s walk, Francisco Lindor’s single, Francisco Lindor’s stolen base and Daniel Vogelbach’s walk all occurred before a third out. No, we got that much out of the home first.

Nimmo was not stranded at third after his shot to right just missed clearing the orange line. To my way of thinking, I wasn’t even sorry it wasn’t a home run. A solo dinger is a run, and the Mets hadn’t done much with first innings and runs lately, but then the bases are bare and the opposing starter’s slate is newly clean. This, a runner on third with nobody out, somehow shaped up as more promising. Brandon’s ninety feet from scoring, and the pressure begins to mount on Spencer Strider. Strider indeed walks Marte, and we’ve got something cooking. Sure enough, Lindor hits one to right to bring in Nimmo, and…

That’s where it begins to get a little too Mets-Braves up in here. Ronald Acuña, Jr., snatches Lindor’s ball before it can get by him, which keeps Marte from going farther than third and doesn’t let Lindor make it to second. It looked like it would bounce to the wall, but there’s Acuña with a backhanded stab that keeps Met runners where they can do minimal harm.

We didn’t know that would amount to “none” yet, but it did. After Pete Alonso struck out and while Jeff McNeil batted, Lindor was determined to get that extra base, taking off from first to steal it. One bag on a stolen base attempt is almost a given these days, and Francisco had no problem making it in safely. The bonus was going to be Murphy’s throw scooting past second base, allowing Starling to trot in with the Mets’ second run, except shortstop Vaughn Grissom did his own grabbing and improbably plucked the ball from its path toward the outfield. Marte could not advance. Lindor could not advance. McNeil could not get them home or get on himself, popping up. Vogelbach walked to maintain pressure on the struggling Strider. Brett Baty presented one more obstacle to the Braves’ starter, but not an immovable object. Brett struck out with the bases loaded.

I’d like to say I didn’t know the game was lost at 3-1, but that was just too many almosts for one half-inning when the opponent is the Braves. Maybe it would have been too many almosts for one half-inning when the opponent is anybody, but the Braves have been the Braves too much and too long, especially too recently, where the Mets are concerned. Almost-ing them isn’t gonna cut it, especially when they’re being definitive about increasing their lead off Mets starter Denyi Reyes.

Reyes gives up a single to Michael Harris II and a homer to Kevin Pillar. Reyes is replaced by Syracuse recallee John Curtiss. Curtiss gives up a homer to Acuña. Instead of cutting into the Braves’ edge further or tying them or passing them, we fall further behind them. Arithmetically, allowing three hitters to become three runners who cross the plate can equal no more than three runs. It felt like more. First, those two instant runs brought in by Pillar, whose last notable act as a Met was getting caught up in the fun and excitement of the thumbs-down kerfuffle of late 2021. Of course, we didn’t have time to snarl at Pillar for pulling a d’Arnaud on us because in a matter of seconds, our attention was turned to Acuña lofting a fly ball to where only the likes of Boeings, pigeons and Cespedii have previously dared to soar. Ronald the Junior placed a Curtiss pitch up in the Promenade boxes, about as high up as Yoenis — a neon ghost we can’t see — scaled in 2016, except not pulled toward the corner, thus making it visually more impressive. Aaron Judge also traveled up to those distant precincts in 2017, but why drag him and his team into this when he have Atlanta and Acuña to provide ample angst?

However and wherever the combined force of the three runs in the top of the first; the bases left loaded in the bottom of the first; and the three runs whacked home in the top of the second landed psychically, it was only 6-1, Braves, mathematically. “Only” seems a silly modifier here, because many opportunities for Atlanta havoc remained and did I mention our starting pitcher had been Denyi Reyes? And our next man up was John Curtiss? And a torrent of better options implicitly eluded Buck Showalter? But unless there’s lots of rain in the forecast, seven-and-a-half innings still awaited. Yes, the Braves could go to town so much in that time that they’d be enjoying dumplings on Main Street, but the Mets were welcome to try their luck in Flushing, too.

Lucky would not describe how Game One turned out, but the Mets at least honored the possibilities inherent in a nine-inning affair. Alonso erased the memory of his first-inning strikeout with a three-run homer in the fourth. It’s not 6-1 anymore. It’s 6-4. Baty not coming through with the bases loaded in the first did not preclude him from leading off with a home run in the sixth, the young lefty swinger besting lefty reliever Dylan Lee, marking another peg up the ladder for a kid on the rise. Ohmigod, it’s suddenly 6-5. Strider didn’t absolutely choke off the Mets; he lasted only five. Though Reyes imploded and Curtiss was greeted rudely, Stephen Nogosek’s return from the IL wilderness went swimmingly for two-and-two-thirds, and by the bottom of the sixth, the opener wasn’t shut.

By the top of the seventh, it was back to being a rout, with Jeff Brigham pitching and that man again, Murphy, producing yet another three-run homer. Nine to five, what a way to lose a ballgame. Except shaky Brave pitching (a pair of HBPs from Old Friend™ Collin McHugh) and shaky Brave fielding (a wild Grissom throw on what should have been an inning-ending DP) in the seventh permitted two runs to close the gap to 9-7. Tommy Hunter’s two scoreless innings maintained the concept of conceiving a desirable outcome conceivable. Ya gotta conceive! One more scintilla of hope arose in the bottom of the ninth when the erstwhile everyday entrant Eduardo Escobar emerged from the dugout to pinch-hit the homer that made a bad loss verge on agonizing. They didn’t quit. They kept coming. But they never came all the way back. Comebacks of that nature generally appear only in a paperback novel, the kind that drugstores sell. Yeah, that’s agonizing.

No time for agony, however. Braves 9 Mets 8 was forty minutes from Braves coming to bat in the top of the first, the Mets taking the field, the enormous scoreboard reverting to blank. Another chance is the beauty of a doubleheader. The likelihood that the Mets will have something to show by the end of it is even more beautiful. The Mets entered Monday not having been swept in a twinbill since cardboard cutouts sat in for spectators during 2020; not having been swept in a twinbill with people in the stands since 2017; not having been swept in a single-admission twinbill with people in the stands since 2016; and not having been swept in a single-admission twinbill with people in the stands at Citi Field since 2012. If you were ever tempted to respond to one of those come-ons daring you to bet responsibly, the Mets winning the second game Monday was as close to a sure thing as existed.

Now, you know there are no sure things in baseball. You might believe the Braves sticking it to the Mets is a sure thing, but look!

There’s Tylor Megill, an actual Mets starting pitcher pitching, and he’s not giving anything up, save for a leadoff hit-by-pitch to Acuña’s left shoulder that conveniently sidelines him for the rest of Game Two. (If you could read my mind, you’d have a hard time searching out my empathy, provided the guy didn’t actually sustain more than a bruise.)

There’s Vogey doubling in a second-inning run off ancient Charlie Morton; he’s been pitching since Shea Stadium stood.

There’s Marte with a single to bring home Baty, who had doubled, in the fifth.

There’s Megill in a spot of trouble in the sixth, bases loaded, two out. If he can get out Eddie Rosario…no, that’s not gonna happen. Rosario doubles to score the first two runners, but at least we got that darn Sean Murphy at the plate.

What’s that?

Replay review?

We didn’t get Murphy?

Of course we didn’t.

Your sure thing is in peril with two on (Morton walked a pair) and two out (Michael Tonkin is on) and Francisco Alvarez up. Alvarez has been looking a little more certain of himself every day. The last time there’d been a baseball game in New York, before the weekend turned all New Yorkers into rainy day people, Alvarez stroked a sweet fifth/last-inning single off the otherwise untouchable Max Fried on Friday night. Maybe because there were no Mets playing no Braves Saturday and Sunday, I read a surfeit into that most recent sample of Francisco’s advancement. As with Baty, you could convince yourself something was happening here. In the home sixth of Game Two on Monday, what it was was exactly clear: a strong double to left that scored both Met baserunners and gave the Mets back their lead at 4-3. McNeil would homer in the eighth to make it 5-3, and David Robertson would save it in the eighth and the ninth to keep it 5-3. You could officially cash in your winning splitting ticket. But remember to bet responsibly.

Not a great Monday for the Mets, as they did lose to the Braves. But not a great Monday for the Braves, as they did lose to the Mets. When you recall how badly Monday started for the Mets, nobody being completely satisfied come sundown rates as a sufficiently happy ending for us.

by Greg Prince on 29 April 2023 12:45 pm It’s not every day your favorite Major League Baseball franchise registers its 5,000th regular-season loss. The day our favorite Major League Baseball franchise registered its 5,000th regular-season loss, the skies clouded up all morning and afternoon; began to mist and drizzle as evening set in; and then began to pour down through the night. Somewhere between the drizzling and the pouring, and ahead of Saturday’s rainout, there was just enough time to get in that 5,000th loss.

The Mets played five innings of losing baseball on Friday night. Well, four innings of tying baseball and one inning of losing baseball. It’s a ratio that doesn’t look so bad until you remember how definitive one losing inning versus none involving winning can be. In this case, after David Peterson and Max Fried each put up zeroes for four innings, Peterson cracked. He almost held it together. Got one out in the fifth. Was on the verge of withstanding a single from Eddie Rosario and a double from Old Friend™ Kevin Pillar when he induced Michael Harris II (how nice knowing there are multiples of young Braves) to bounce to Brett Baty. Baty in the rain stood and thought about what to do with the presumably wet baseball for a spell, but ultimately and wisely gripped and threw it home to Francisco Alvarez. Alvarez didn’t have to tag Rosario, given that Rosario veered from the basepath toward Astoria, which even a bleeping Brave can’t get away with.

With two out, Pillar on third and Harris having moved up to second while Baty took his time throwing home, all Peterson, who had appeared sharper than he had the rest of April, had to do was take care of Ronald Acuña, Jr. The Mets haven’t yet figured out the best way take care of Acuña is to deny him entry to Citi Field. A solid single brought disgraced Bench Mobster Pillar home with the first run and pushed Harris to third. Really, it didn’t matter where Harris was pushed. He and Acuña would be powered across the plate by the next batter, Matt Olson. Olson rudely directed a baseball into those pavilion seats in front of Shea Bridge.

It was 4-0 and raining. You hoped both conditions would be temporary. You knew permanence loomed because of the ancient rule that says five innings can be an official game if the skies are angry enough to lop off the forthcoming four. The Mets could have scored four or five in the bottom of the fifth to forestall permanence let alone defeat in their role as the home team potentially leading at the end of five soaking innings, but that’s Max Fried out there on the mound. As long as he didn’t slip, fall and not get up, he was gonna take care of the Mets as seems to be his wont. Max Fried’s ERA in 2023 is 0.45. It’s not just us.

Max got through the fifth with minimal fuss. The rain fell with maximum impact. The tarp covered the diamond. I flipped to the Islanders ending their season in overtime. Somewhere along the way I remembered to check back in on the rain delay. It became a rain-shortened final of 4-0. The Mets’ season didn’t end. It didn’t continue strongly, but, we’ll continue to tell ourselves, it was just one game.

***The Mets have now lost 5,000 just one games. We didn’t bury the historical lede, so let’s exhume it before the rain stops and, sooner or later, we experience our 5,001st. It’s inevitable. You lose some, you win some. We just happen to root for a team that’s lost a bunch more than it’s won since its birth.

When Fried and Pillar and Acuña and Olson and the rain conspired to defeat the Mets, it knocked us 333 games below .500. Not for this year, but for all years. Our current lifetime record of 4,667-5,000 —— plus 8 ties — carries a lifetime winning percentage of .483. For context, if you apply .483 to a 162-game season, you’d have a team that goes roughly 78-84 every year for nearly 60 seasons. The Mets are in their 62nd season, but a few of them have been shortened by strikes and pandemics and whatnot. The Mets have never posted a 78-84 record at year’s end. The closest they’ve come is 77-85 in 2011, 2018 and 2021; 77-84 in 1991; and 79-83 in 2010 and 2014.

We got to L5K, and it didn’t even take nine innings. If you remember any of those six seasons, that, on average, is what our entire life as Mets fans has been. Of course we don’t take average into account over the long haul. Extremes make for punchier examples, and we’ve sure taken our punches since coming into this world. You know, if not by heart then in your gut, that we lost our first nine games to begin life, and 120 of our first 160. The losing continued at a slightly less self-defeating pace for the next five or so years. After dropping a Sunday doubleheader at Shea to the Cardinals on June 2, 1968, the Mets’ lifetime record was 341-675.

The Mets were off that Monday. Tuesday they played in Chicago. Jerry Koosman shut out the Cubs, 5-0. From that day forward through Friday night — June 4, 1968, all the way to that tarp staying put on April 28, 2023 — the Mets’ record has been 4,326-4,325. For nearly 55 years, the largest friendly sample size we can cobble, the Mets have been a winning baseball team. Not enough peaks and far too many valleys for our taste, but cumulatively, the past 8,651 Mets games played to a non-tying conclusion have indicated we root for a team you can’t, on average, call a loser.

Even if that’s a soggy hook on which to hang one’s hat after five innings drenched by Max Fried.

***The Mets’ lifetime record versus the Braves, both the Milwaukee and Atlanta versions, is now 411-496, meaning nearly every tenth Mets loss is a loss to the team we’ve considered our archrival for a couple of swaths of our history. Ever since Atlanta became a powerhouse and concomitant bane of our existence in the 1990s, we might have wondered what we ever did to make them this mad.

To discern an answer, you’d have to fly back in time, over Acuña Jr. and Harris II and the only Fried I’m aware of; over the miseries inflicted by the likes of Freeman and Chipper and those Cy Young pitchers far more annoying than Max Fried; over the brief era when Dale Murphy and Bob Horner gave credence to the America’s Team hype; even before Phil Niekro’s knuckler began to beguile the National League in earnest.

You have to go back to practically the beginning, to when the Braves were Milwaukee’s best. You have to go back to the 1962 Mets ever so briefly hinting that they might not be “the 1962 Mets”. After that 0-9 start, the ’62 Mets got on a roll. Maybe it was just about averages averaging out or regression to the mean or some fancy statistical term that explains eventually you’re gonna win some even if you mostly lose some, but from April 23 to May 20, the 1962 Mets were a winning team, going 12-10 in their previous 22 games. For a team that had played only 31 times in their life, you can’t dismiss 22 games as a small sample size. And the last set of opponents who would dare to slough off the surging Mets’ success would have had to have been the Milwaukee Braves.

Against the 1962 Mets, the 1962 Braves, in a pair of series spanning ten days, went 4-5. That included two doubleheader sweeps over the outfit that featured Henry Aaron, Eddie Mathews, Warren Spahn and a young catcher named Joe Torre. The already laughable Mets took the measure of an aggregation of Hall of Fame talent, and who was laughing now? When the Mets completed their second sweep of those Braves, at County Stadium on May 20, their season and lifetime record was 12-19. Never mind that the eighth-place Mets were leading both Houston and Chicago in the standings and sat only a game from Milwaukee for seventh. Consider the long view. Since 1962, nine different Mets teams have not posted a better record than 12-19 over their first 31 games, which is to say that for a brief, shining moment, the 1962 Mets were en route to not being the worst Mets team (or worst team) ever, and it was largely because the Braves couldn’t beat them.

Then the 1962 Mets continued their road trip, lost 17 in a row, and haven’t been within seven games of .500 lifetime since. They haven’t been within 300 games of .500 lifetime since 2009, but that’s another story. The story we’re trying to tell at the moment is that of the underlying grudge we’d like to believe might be motivating the Braves to beat the Mets as often as they do in the modern era. We’re going with embarrassing Atlanta’s Milwaukee ancestors early and often and our about-to-emerge habit of plucking their unwanted players and giving them the opportunity to blossom in the years following 1962 as the most logical reasons we can come up with. Honestly, that should have been enough to get a potential archrival’s DNA chopping mad.

Carl Willey, the Mets’ veritable ace pitcher of 1963, was somebody the Braves didn’t want anymore. The righty from Cherryfield, Me., languished in the middle of their rotation, somewhere south of Spahn, since his rookie season of 1958. The promise he’d shown initially evaporated a little more each year until Milwaukee was happy to take a chunk of Mrs. Payson’s cash in exchange for his services in Spring Training of ’63. Willey rewarded Met management’s interest by throwing four shutouts in the year ahead, or four more than all other Met righties had combined to throw over the club’s first two seasons. One of Carl’s blankings, a two-hitter over the Phillies, served as pleasing background for Jimmy Piersall’s backwards trip around the bases when Jimmy hit his 100th career home run. Casey Stengel was famously irritated enough by Piersall’s attention-craving act to promise to remove him from the roster on the basis of the Polo Grounds being big enough for only one clown. Willey, on the other hand, inspired nothing but faith in Casey. The night after the Piersall contretemps was a game that technically didn’t matter, but emotionally mattered like nothing before it: the first Mayor’s Trophy Game. How important was it to Mets fans, let alone the Mets’ manager, that the Mets best the Yankees in the Bronx? Stengel brought in Willey to pitch four innings of relief on no days’ rest to make sure the Mets’ lead over his former employer didn’t get away. It didn’t…even if Carl got away from the Braves.

Ron Hunt, the Mets’ first attention-getting youngster (attention received for the right reasons), was also somebody the Braves didn’t want anymore. Ron was a minor leaguer in the Milwaukee system, never getting beyond Double-A for four seasons in the Brave chain. Another cash deal ensued. It paid off handsomely when Ron insinuated himself into the Mets infield in 1963, finished the season as National League Rookie of the Year runner-up to Pete Rose, and literally starred at second base during the Midsummer Classic at Shea in 1964, chosen ahead of every keystone sacker in the senior circuit, including that Rose kid. True, Pete would last longer in Cincy than Ron would in New York, but the Reds had had stars before. Hunt was our first ever, landing in our lap courtesy of the Braves.

In the second half of 1964, while Ron was rising and Carl was recovering — a line drive got him in the jaw in Spring Training and pretty much guaranteed he’d never again be as effective as he’d been the year before — the Mets picked the Braves’ pocket once more. This time, it wasn’t merely money Milwaukee sought. They wanted the Mets’ veteran righty, Frank Lary. The Braves were on the periphery of the pennant race. Maybe Lary would lift them from the middle of the pack into true contention. To get the man known alternately as the Mule and the Yankee Killer (one guess as to which one we consider the most flattering appellation), it would take some cash, yes, but also a 22-year-old righthander who’d been putting up some pretty valuable numbers of his own in the minors since 1961.

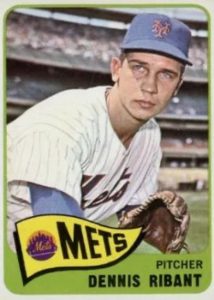

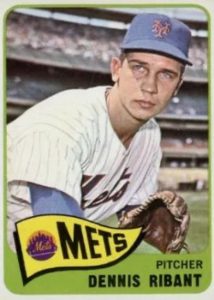

The Braves sent the Mets Dennis Ribant on August 8, and before August was out, Dennis Ribant appeared ready to make us forget Carl Willey wasn’t what he used to be. Ribant was making us look forward. That was the direction fans of a third-year expansion club that had finished tenth and tenth, and was about to finish tenth again, needed to look. We had to have something and someone to anticipate, someone who’d take part in a future that would turn the present of last place into the past as soon as possible.

On August 9, Dennis the Met made his major league debut in relief. Three days later, he made his first start. It didn’t go particularly well: five earned runs over six innings at Pittsburgh. The resulting 5-4 loss dropped the Mets 44 games below .500 on the season and 184 games below .500 in the still nascent life of the franchise. In other words, more of the same.

Five days after that, Dennis Ribant gave Mets fans nothing of the sort. He gave us a glimpse of possibility. At Shea Stadium, in his first home start, Ribant shut out those same Pirates — Hunt’s All-Star backup Bill Mazeroski at second, budding Metkiller Willie Stargell at first, the already great Roberto Clemente in right — on four hits and zero walks in a 5-0 Mets triumph that stirred the imagination. The kid whose future the Braves opted out of fanned ten Buccos. You know how many Met pitchers had thrown a shutout while striking out a double-digit total of batters, Hall of Fame-bound or otherwise? Before Dennis Ribant, there were none.

Ribant had us looking in the right direction. With Frank Lary and whatever financial resources Mrs. Payson had provided them over the past two years, the Milwaukee Braves didn’t crowd the 1964 National League pennant race to any meaningful extent. They finished fifth. In the offseason, they’d sell Spahn to the Mets. Lary, too, making the Mule and the Yankee Killer also the first Recidivist Met. By 1965, the Braves were already making plans to move to Atlanta in 1966, setting a goodwill template for the Oakland/Las Vegas Athletics of the 2020s. Neither the Milwaukee nor Atlanta Braves were the Mets’ primary concern heading into ’65. We’d have to figure out what to do with all our ex-Braves pitchers.

Spahn would have his moments, as one would imagine the owner of 356 wins and counting when he joined the Mets would, but Warren wouldn’t last in New York. The 44-year-old lefty legend would be released in July and seek his last ounce of contention pitching for San Francisco. Lary, 35, had enough left to entice another pennant hopeful, the White Sox in the other league, to acquire his services from the Mets shortly after Independence Day. Willey, 34, had to go down to Buffalo to regain his form, and his final start of the year showed he could still pitch. He went nine in beating the Phillies on September 25. That turned out to be the final appearance of Carl’s major league career, as he chose retire to Maine rather than chase any further innings on the mound. In fact, none among this trio of ex-Braves pitched in the bigs after 1965.

Ah, but we were looking ahead. We had Dennis Ribant. We had the young man who’d shut down the Pirates in 1964. We didn’t get a game nearly as good from the kid for most of ’65 (he’d be back in Triple-A by June), but toward the very end of the year, on September 28, Dennis threw eleven shutout innings against the team he’d tormented thirteen months earlier. Unlike that breakthrough in August of ’64, the Mets didn’t score a whit for Ribant and he was no-decisioned. Four days later, Rob Gardner would pitch fifteen innings of shutout ball and the entire team was no-decisioned in what went into the books as an 18-inning 0-0 final, the fourth of those eight aforementioned ties in Mets history. It was helluva week for the unrewarded.

Ribant’s and our reward would await in 1966. That, in an individual pitching sense, was the year we had been waiting for since 1962. The ex-Braves farmhand came of age as a Met starter. Having pitched credibly out of the bullpen in April, Wes Westrum handed Ribant the ball against the Cubs on May 8. Dennis went nine and got the win. In June, he notched another shutout victory, over the Reds. His place in the rotation secure, he took off as no Met pitcher before him had. This is not hyperbole. The Mets had some starters do well with little to show for it between 1962 and 1965. Willey deserved better than to go 9-14 in 1963, but he finished with a losing record nonetheless. Al Jackson won 13 for a team that lost 111 in 1963. He also lost 17. Records of that nature came with the Metsian territory.

Cartographer Dennis Ribant drew a new Met map in 1966. He started ballgames and he started winning — him and the Mets. On September 6, when he once again shut down the Reds, his record stood at 11-6. For five years, the idea that any entity within the Mets’ realm could claim an overwhelmingly positive statistical ledger bordered on absurd. Yet here was this still young man we got from the Braves and, unlike a Spahn or a Lary or a Willey, he had his prime on the horizon. On the cusp of turning 25, he was pretty much in the thick of it. Not only was he five games over .500, his earned run average was 2.67. That’s what a good pitcher posts. Dennis Ribant was a good pitcher pitching well and not in hard luck.

Even with a little falloff in fortunes over the final few weeks of 1966, Dennis Ribant finished with the kind of record unfamiliar to the Mets starters who preceded him: 11-9, with an ERA of 3.20. The Mets didn’t finish last. The Mets didn’t lose 100 games. The Mets had a live right arm that had already demonstrated it could consistently get hitters out and have something to show for it.

Come 1967, the Mets would have two players to show for Ribant’s 1966. The Pirates, who perhaps remembered what Dennis had done to them as he was coming along, traded two of their own D-men — Don Bosch and Don Cardwell — to the Mets to have Ribant (along with outfielder Gary Kolb) board their ship. There’s not much need to weave a pattern of foreshadowing from here, not if you’ve been a Mets fan long enough to recognize certain names. Bosch was supposed to fill the Mets’ long-gaping hole in center field. To put it kindly, he didn’t. Cardwell was another in that long line of veteran pitchers in whom the Mets placed their trust when they weren’t quite sure what to do with their youthful counterparts. He started Opening Day 1967 because they weren’t quite convinced another good-looking young righty, only 22 and holding no major league experience, should be granted the honor of that assignment.

So Tom Seaver (whose name fell into a hat once his contract slipped out of the Braves’ hands) waited until the second game of ’67 to debut, and in a matter of minutes, was the best pitcher, young or old, the Mets ever had. Cardwell’s role as ace was evanescent. Turned out Don would have a more important part to play in the Mets teams that were coming together in 1967 and 1968. There’d be a lot of young pitchers proving themselves more than capable of carrying the load, but that kind of staff inevitably benefits from a savvy veteran. The swiftly arriving future would belong to Seaver, Koosman, Ryan, McAndrew and Gentry. Enough of the present that accompanied it into existence was spoken for by Cardwell. Don won 20 games for the Mets in the final three seasons of the 1960s, including eight in 1969.

Perhaps had the Cardwell trade never been made, we’d be just as easily listing the name Ribant alongside those other then-young pitchers who made the 1969 Mets “the 1969 Mets”. The story, as we tell it now, has Don playing a vital mentoring role, not to mention an important one that involved starting 21 games in ’69. As it happened, Ribant would pitch for a team that would win the World Series in the late 1960s. He was a Detroit Tiger in 1968, if not for long. The Pirates had sent him to his hometown team after a decent enough 1967 (9-8). The Tigers swapped him to the White Sox for experienced bullpen help (38-year-old Don McMahon) midway through ’68. There’d be some bouncing around from there. Dennis last pitched in the majors in 1969 and in the minors in 1973. Ribant lived fifty years beyond his last professional pitch, dying this past week at the age of 81.

If, like me, you never saw Dennis Ribant pitch as a Met, you can be comfortable historically slotting him in that circle of players who necessarily had to move on to build the 1969 world champions (who, incidentally, swept the Braves on their road to the World Series). Ron Hunt had to go in order to get Tommy Davis, and Tommy Davis had to go to in order to get Tommie Agee. Tommie Agee had to be in center field in order for the Mets to go all the way, but both Hunt and Davis expressed regret they couldn’t stick around long enough to experience 1969 as Mets. Could you blame them? Each man, who played deep into the 1970s, made the Mets the best they could possibly be in the years prior to 1969, when the franchise was piling up losses despite their individual standout efforts.

“It killed me” to be in that circle, Ribant told author Bill Ryczek. “It broke my heart when I was traded to the Pirates. It took a while to get used to it because I loved New York. I was the first Met pitcher to have a winning record. It was a big disappointment.”

Technically, disappointment was what existed around Ribant. Actually, maybe what defined the Mets whose ranks Ribant joined wasn’t disappointment. How can you be disappointed when you’ve learned not to expect anything good? By pitching as he did that first start at Shea in 1964 and then for the bulk of 1966, Dennis upended that sad state of affairs. Before it could be clearly forecast that the Mets were one day fairly soon going to be the best in their game, we needed a sign that that day was coming, even if that sign didn’t lead directly to that day. In the middle of the 1960s, when Met losses were the rule, Dennis Ribant proving the exception represented a life preserver to the hopes of Mets fans who lived for the day when being a Mets fan would be about expecting something good.

That’s quite a circle to be in, too.

by Jason Fry on 27 April 2023 11:28 pm This recap begins with a confession.

Emily and I had tickets for Thursday night’s game, obtained weeks ago in exchange for a smallish charitable contribution. My 2023 debut at Citi Field was nigh, and with it the chance to demonstrate that I was not, in fact, jinxed despite having gone 0 for 2022 as an attendee, with the last two losses against San Diego when losing a ballgame was a really bad idea.

But the seats were up in the rafters, and when I left work for a midafternoon walk I quickly retreated inside, because the outside world was terrible — a gray, clammy parody of Scotland invented by someone who wanted to show his disdain for the place. I thought about night coming, and how much colder it would be, and in the back of my mind I was also thinking about 2022 and how horrible the Mets had looked against the Nats of late.

I texted Emily, who didn’t need a lot of coaxing. We bailed, agreeing that if Joey Lucchesi threw a perfect game in his matchup with old friend Trevor Williams, we’d find a way to live with our shame.

Apologies if it’s a SPOILER, but Lucchesi did not throw a perfect game. In fact, very little that transpired Thursday night came anywhere close to perfection. The Mets coughed up 1-0, 4-1 and 7-3 leads, dissolving in a flurry of walks and hit batsmen and shoddy defense and plain old bad luck. Their salvation, if that’s the word, was that the ineptitude they set in motion spread like an oil slick of bad baseball, engulfing everything in its vicinity. Sure, Tommy Hunter hit two dudes and Brooks Raley gave up a horrific hairball of a grand slam, but the Nats sent out ex-Met Erasmo Ramirez to be a punching bag and then leaned too hard on an exhausted Mason Thompson, who got strafed. The slick o’ suck looked like it was going to coat David Robertson in ignominy as well, but our Plan B closer overcame an initial stagger to deny the Nats and send the Mets home triumphant, at least to the extent that pulling out a 9-8 win over the Nats to avert a sweep can be considered a triumph.

Really, they didn’t win so much as they survived. All wins count the same, but some come with mental asterisks. I tried to convince myself I regretted my unused ticket, but then I thought about what it would have been like high up in the Promenade, huddled in misery as C.J. Abrams skipped around the bases after a grand slam, instead of settling for muttering while sitting in the warmth of my mom’s living room. (She’s finishing up her first month as our neighbor in Brooklyn after leaving Virginia.) No, I decided, I’d made the right choice. Shivering in the LaGuardia flight path would have been terrible — and who knows, maybe the observer effect would have come into play, perhaps urging Lane Thomas along the proper route as Jeff McNeil‘s potential triple was still hanging in the air.

I know that’s insane, but when you go oh for a calendar year, you think about things like that.

It wasn’t all bad in Metdom, granted. Beyond the obvious fact that they won the damn thing, 9-8, Lucchesi looked useful if not as scintillating as he did in San Francisco; Brett Baty collected a homer among his three hits; and Starling Marte showed much-needed signs of life. Best of all, Pete Alonso — who’d spent Tuesday and Wednesday looking woebegone even by Unhappy Polar Bear standards — had a terrific at-bat in the eighth with Marte on third, one out and the Mets down by a run. Facing Thompson, Pete refused to go out of the strike zone when offered two very tempting sinkers, then got one over the plate and smacked it up the gap for a game-tying double. When out of sorts Alonso can be lured into slashing at balls he couldn’t hit with an oar, but that AB looked like the ones he’d been having before the team’s record scratch midway through the Giants series, and that’s a very good sign for Pete, the Mets and perhaps humanity.

I only wish I’d been there to … no, I actually don’t. Things turned out right with me a few miles away, I’m warm, and the Mets won. Good enough.

by Greg Prince on 27 April 2023 10:17 am When the Mets returned to what we’ll loosely call action Tuesday night, they were the inverse of what Annie Savoy saw in her Durham Bulls one extraordinary June and July where they’d played with joy and verve and poetry. That will happen after a cross-country flight that follows a West Coast road trip, we were informed, as if everybody had been handed talking points in advance of the Nationals series. The Mets ceased being gangbusters late in their swing through California, losing their last two in San Francisco to take the edge off what had been a 7-1 tear at the expense of opponents both downscale and upmarket. Shea la vie, we might have told ourselves. Seven wins versus three losses is still a pretty good ratio, and one can convince oneself to shake off a sub-so-so performance if jet lag becomes Met lag.

Wednesday night at Citi Field didn’t put me in mind of Bull Durham. It put me in mind of Moneyball, specifically the scene in which Billy Beane is trading Carlos Peña and Jeremy Giambi to keep Art Howe from playing them and, as a kicker, “Menechino, Hiljus, Tam are all being sent down.” That was just me projecting, though, wishing we could disappear a fifth of the roster and, a montage or two later, win twenty in a row.

Terrifying? Maybe frustrating. Either way, Gore from Washington opened our eyes to something deeply disturbing. The inconvenient truth of the Mets at the moment is they’ve lost four in a row, their last two against the Eastern Seaboard version of the Oakland Athletics, the Washington Nationals, who, since landing in New York themselves, have forgotten they were supposed to lay down and die for the benefit of the mighty, mighty Mets. Led by MacKenzie Gore, neither a chad nor a doubt was left hanging. Gore won. The Nats won. For a second night in a row amid the chill winds off Flushing Bay, the Mets appeared to barely compete. It was a 4-1 blowout.

Kodai Senga, once our secret weapon, seems to have suffered from exposure. It took five starts for the ghost fork to become familiar to opposing hitters. Senga’s still got the stuff, but he needs the command. It’s a little evocative of Sid Fernandez c. 1985 wherein El Sid (a real person, not a movie character) could baffle hitters but also be waited out by them. Senga struck out seven over five innings, an impressive number. He also walked four, an alarming amount.

The Mets’ hitters, meanwhile, accomplished next to nothing at the hands of Gore, the leading prospect the Padres had to surrender to acquire Juan Soto. In context, it wasn’t a bad exchange for Washington. The context that concerned us was the six-inning stint Gore threw Wednesday, with one run allowed on four hits and two walks amid ten Met strikeouts. The Mets air promotional spots roughly every half-inning insisting, “Baseball hits different here.” Maybe it would if it could make meaningful contact.

Even the one Met run was a bit of a gift, facilitated by an Eduardo Escobar triple that eluded Lane Thomas in right when it was still a catchable line drive. You’ll take what you can get. In Oakland, at the beginning of the California trip, the A’s gifted the Mets a year’s supply of walks (giddily accepted) and then proceeded to be not quite good enough to overcome one-run deficits in the following two games. I was left thinking after our sweep at Possum Central Coliseum that a slightly more seaworthy foe would have taken one or both of those games, but you play who you play.

The Mets played a slightly more seaworthy foe the last two nights and lost both times. Long season and all that — there’s a reason baseball movies don’t rush the dramatic surge in fortunes — but this doesn’t look like the team that went to Los Angeles and overcame everything but vintage Clayton Kershaw. Nor did it resemble the walking, homering offensive machine that allowed us to not dwell on Senga’s less than wholly effective outings in Northern California, where 26 runs were plated on Kodai’s behalf. It certainly doesn’t look like the team we considered, based on the 2023 roster’s similarity to 2022’s cast, capable of slowly grinding opponents to a fine dust. Perhaps that’s harder to do when you have only 20 seconds between pitches to inflict your core competencies on a game’s direction. Not sure right now what this team looks like beyond naggingly frustrating.

Maybe Joey Lucchesi will save us again. He always has in 2023.

Well-earned fan angst is the throughline in the new episode of National League Town, available wherever else you need your baseball anxiety semi-reasonably articulated.

by Jason Fry on 25 April 2023 10:17 pm The good news: The Mets fixed the New York-Presbyterian patch, the one that was unreadable and looked vaguely like an ad for the Phillies, Dunkin’ Donuts or some nightmarish chimera of those two entities. It annoyed Steve Cohen, and when you’re Steve Cohen and you’re annoyed, people hop to it.

The other good news: Nope, that was it.

The Mets got back from the West Coast Monday morning at around 6 a.m. So were we repeatedly informed by GKR, mercifully returned as accompaniment after two days of interloper announcers from national empty-calorie networks. Keith Hernandez led the charge, talking repeatedly about how returning to the East Coast after a long time near the Pacific is hard, and how teams tend to come back a little flat.

A little flat? The Mets looked like they’d returned to New York on the underside of a steamroller. They could have been slipped under your door five at a time. Edwin Abbott Abbott could have written a book about them.

They didn’t hit — though Josiah Gray might have something to do with that, as he looked like he’s figured a few things out since we last saw him in his accustomed role as a Met punching bag. They didn’t pitch — Jose Butto couldn’t get his changeup over and Jimmy Yacabonis had the roof cave in on him, though he had a little help bringing it down. And they didn’t field — honestly, when Francisco Lindor and Luis Guillorme both make misplays in the field, you know it’s not your night.

They didn’t do anything that resembled anything you’d pay money to see — the game was simultaneously boring and infuriating, a slow-motion car crash to which I’ve already dedicated more words than is deserved.

Still, way to fix that patch.

by Greg Prince on 24 April 2023 1:31 pm Francisco Alvarez went up and got it. The pitch, from Tyler Rogers, was measured at 3.87 feet off the ground. It looked higher. It flew higher. It flew over Oracle Park’s left field fence, which is eight feet high. After going up, getting it, and sending it for an aerial ride, Alvarez had every right to feel at least as tall as the wall he’d just cleared. Francisco in San Francisco had broken through some barriers. His first home run of the season. The first homer of the season for any Mets catcher. The first extra-base hit of the season for any Mets catcher. Alvarez, Tomás Nido, Omar Narváez, Duffy Dyer — you name them, none of them had done anything more than single. And they hadn’t singled all that much as New York Mets since 2023 began. When 2023 began, Alvarez was a Syracuse Met for the moment, a half-baked Met a moment later, rushed out of the oven lukewarm because Narvaez had gotten hurt. The Met prospect of Met prospects was back with the big club before he was ready, not unlike the scenario that developed at the end of last September, save for the overtones of desperation that enveloped the Mets as they traveled to Atlanta.

Little this April has alleviated the impression that young Francisco isn’t fully honed to face big league hurlers. The eye test says he’s looked lost. The numbers suggest the eyes are operating 20/20. As Sunday night’s game got going, a friend messaged me: “I saw something I’ve never seen before. When they showed Alvarez’s stats, he was -29 OPS+ I’ve never seen anyone with a negative OPS+.” No, you don’t detect that kind of stat that often, especially with pitchers having exited the statistical column in question. In a nutshell, 100 is an average OPS+. Position players aren’t doing very well relative to the rest of the league if their on-base percentage and their slugging percentage taken together spits out an OPS+ in positive double-digits.

To be showing what Alvarez was showing entering Sunday evening, you’d usually have to be somebody who isn’t expected to hit at all. Last season, the Mets had four bit players who produced an OPS+ that started with a minus-sign. If you’re more than a bit player and your OPS+ languishes beneath zero, you’re eventually not going to play even a bit. Two (Deven Marrero and Travis Blankenhorn) combined for nine plate appearances, the epitome of a small sample size. Two (Terrance Gore and Ender Inciarte) mostly pinch-ran. Nine years ago, when Bartolo Colon took swings on a regular basis and his batting helmet flew off his head nearly as often, his OPS+ over 69 plate appearances was -77. Two years later, in the season he homered and generally appeared competent with a bat in his hands, Bart had jacked it up to -30 in 65 PAs. It wasn’t going to tame the universal DH tide, but you can’t say Colon didn’t improve.

There’s hope for everybody. There’s hope for Francisco Alvarez. There’s hope, there’s expectation, and there’s the acknowledgement that, at 21 and claiming fewer than 50 games of Triple-A experience, the kid is going to go through this phase of his major league offensive life as undercooked and overmatched. He blended both states, grounding into a one-out bases-loaded double play on a three-two pitch from Giants starter Ross Stripling to kill a Met rally in the second inning. Somebody’s working somebody when the count goes full. One potential ball from giving up a run or more, the pitcher had this hitter right where he wanted him.

Two innings later, Francisco again came to bat with the bases loaded, again against Stripling, this time with nobody out. The Mets operate with a short bench. It was early. The pitcher was obviously in trouble. “Can’t we pinch-hit here?” streaked across my mind. I’ll be as patient as possible with a 21-year-old top-ranked prospect in the medium to long haul. In the situation that existed at that instant, the Mets trailing by one and me having been reminded how an OPS+ can plunge below zero, I had no patience. I didn’t really think the ramifications or logistics through. I just wanted Francisco Alvarez to not bat with the bases loaded.

This time, Stripling had Alvarez in a one-two hole before striking him out swinging. Gabe Kapler proceeded to change his pitcher (Rogers for Stripling), Buck Showalter proceeded to pinch-hit for his next batter (Mark Canha for Luis Guillorme) and, in a matter of minutes, helped along by an Old Friend (clank, clank, clank went Michael Conforto’s defensive folly), the Mets turned what had been a 2-1 deficit into a 3-2 lead. They were ahead by one in spite of Alvarez.

In the bottom of the fourth, they were behind by one again. In the top of the sixth, Alvarez was still being given the benefit of every doubt, though letting your starting catcher bat with two out and nobody on and only one catcher on the bench with another three innings to go isn’t an extravagant vote of confidence. It’s just a baseball game. It’s ordinary managerial behavior. What was to be lost by another Alvarez groundout or strikeout?

We didn’t find out because this time Francisco found his pitch, up in his eyes. Alvarez is listed at 5-foot-10. If the pitch was 3.87 feet off the ground, it wasn’t really up in his eyes, but we’re going with the eye test here. It was, at the very least, a high strike (depending on home plate umpire Roberto Ortiz’s capricious interpretation of the zone). Wherever it was, the rookie who probably shouldn’t be engaged in a major league timeshare this month, went up and got it. That’s what he’ll have to do on occasion. Go up and get it, literally and metaphorically. The Mets did the “up” part when they promoted him. Their other healthy MLB-experienced catcher at Syracuse, Michael Perez, lingers outside the 40-man roster. When Narvaez got hurt, the big club itself was the one out of options.

Alvarez, who came up when the Mets arrived at Citi Field for their Home Opener, might fit better in his road uniform, because he’s existed in a gray area. Not exactly the starter. Not exactly the backup. Not exactly who you want in the box with the bases loaded. Not exactly who you want to see being kept in reserve at this stage of his career. This stage, incidentally, is still pretty larval.

Francisco’s homer knotted the score at four, which was great. The Giants unknotted the score to make it 5-4 in the eighth. Less great. Alvarez led off the ninth. Camilo Doval struck him out on four pitches. He also struck out Mark Canha and grounded out Brandon Nimmo. It took a team effort to lose the final game of an otherwise satisfactory (7-3) road trip. Tylor Megill wasn’t sharp the first four innings. Drew Smith surrendered that go-ahead run late. Showalter said something about preserving David Robertson and Adam Ottavino for another day instead of deploying one of them to keep things tied at four in the eighth. Neither veteran pitched at all in this four-game series, so we’re left to wonder if their experienced arms are altogether OK. Experience isn’t always everything.

Promise is something to behold. Alvarez has promise. Brett Baty has promise. He has yet to light it up, either, in his second unplanned go-round. The short video clips from Syracuse are so tantalizing when we see guys like these (a cohort that includes Mark Vientos and Ronny Mauricio) clear fences and circle bases. We tend to forget our minor league stars are facing minor league pitching. We don’t ask for details as we dream on our kids. We and they inevitably wake up to pitchers who are more likely to know what they’re doing than the fellas in the International League. Baty’s OPS+, for the moment, sits at a scant 45. Alvarez’s has surged to 11.

That’s for the moment. Nobody except the wholly unreasonable is asking these kids to carry this club. This club carries itself pretty well as is. Carrying their share of the load will come with time. Our patience is appreciated if not always forthcoming.

by Jason Fry on 23 April 2023 11:24 am I don’t remember when the thought first crawled into my brain. It might have been when our starting pitcher had strained his neck watching another ball explore the outermost confines of Oracle Park. Or perhaps it was when said starting pitcher was chasing down a ball caroming between fielders while Giants ran around the bases with more merriment than I was feeling. Neither of us those necessarily narrows it down with exactitude, so let’s just say it was somewhere during an excruciating 80-minute stretch of televised sports best described as “baseball-adjacent.”

Whatever the timing, here was the thought: I’ve never seen David Peterson and Aaron Heilman in the same place. Hmm. Do you think it’s possible that….

Ha ha. OK. Of course not. Heilman is 44 now, and whatever he’s doing, I sure hope he’s not on his couch remembering what a pain in the butt West Coast trips were. More than that, Heilman was one of the first Mets I identified as a Jonah — he hasn’t been a Met for a decade and a half, but I can close my eyes and see his hangdog mien and slumped shoulders as if I last saw them yesterday. Peterson isn’t a Jonah. He doesn’t go about his business with a little black cloud eager to dump rain, and you don’t automatically expect disaster when he reports for duty. He’s just a young pitcher trying to overcome the limitations of his initial skill set while enemy teams backed by ferociously good scouting and analytics departments work to exploit those limitations. That’s so much harder to do than those of us moaning “THROW STRIKES!” from the cheap seats or our living rooms would guess.

But I still couldn’t get the thought out of my head. Because, yeah, I was the guy moaning “THROW STRIKES!” from my living room. Right now Peterson is inefficient and frustrating, missing corners and the top of the zone and then leaving pitches in the middle, with disastrous results. I booted him off my fantasy team in the middle innings; the Mets might want to do the same with their actual team, giving Peterson’s innings to Joey Lucchesi and offering Jose Butto another turn in the upcoming stretch of ALL PITCHERS ON DECK. Or Dylan Bundy. Or, well, someone who isn’t David Peterson.

Some of that is fan pique, which I acknowledge falls a fair distance short of substantive analysis but certainly has its place here. (If poor Aaron Heilman is reading this, he’s rolled his eyes and muttered, “Dude, let it go already” in the exact same tone with which I urged that strikes be thrown.) But it also might be a good idea: Peterson’s slider is MIA, it’s affecting the rest of his approach, and it has to be affecting his confidence.

The late Marty Noble once answered a mailbag question about Heilman by pointing out the Mets didn’t have better options and asking the aggrieved fan, “Where do you want him sent? Prison?” Fair enough, and it’s true that now as then, better options aren’t immediately obvious. But maybe the Mets ought to explore them anyway, while Peterson searches for that slider in Syracuse. Baseball’s really hard, from out pitches turned disobedient to enemy hitters doing the pitiless things they’re paid to do, and at least for now, Peterson looks like he could use a setting where the wattage of the spotlights are lower along with the stakes.

by Greg Prince on 22 April 2023 12:00 pm What Joey Lucchesi did on Friday night was, in the pitching-short present, necessary and appreciated. Off the radar for nearly two years while he underwent and rehabbed from Tommy John surgery, Joey the Churve stormed back from obscurity and Syracuse to do more for the Mets in one outing than he had done the whole time he was healthy in 2021 — and do more than any starting pitcher has done for them in 2023. There was a period when a starter going seven innings was a pretty good day at the office, but nothing that stopped the presses. That period hasn’t existed since people knew what stopping the presses meant.

Although I saw Lucchesi’s feat in San Francisco compared to Matt Harvey coming back from a year of inactivity in 2015 and shutting down the first opponent he’d seen since 2013, it reminded me more of a game from 1975, when Mets were Mets, and Tom Seaver went at least seven innings in 27 of his 35 starts, completing 15 of them. I don’t need much of a nudge to be reminded of games from 1975, of course, even if they weren’t started by Seaver. The one I was moved to think of was from the middle of August of that year. It was pitched by Craig Swan, who was making his season debut. Swan was judged a disappointment in 1974, with nobody realizing he was pitching with a stress fracture in his right elbow. Next time you hear about precautionary imaging at the drop of a hangnail, remember that promising young pitchers used to be encouraged to rub dirt on whatever hurt. My, how far we’ve come as a species.

After being diagnosed correctly and having his cast removed, Swan spent all of 1975 regaining his strength and velocity at Tidewater, leading to his recall on August 16, against the Giants at Shea Stadium. His return set a promising precedent for the likes of Lucchesi generations later: eight-and-a-third innings, two earned runs (one let in by closer Bob Apodaca) and his first win in what felt like forever. It had been about 14 months. Swan was 24 and had been absent from the Mets plans until injuries forced their hand. It might as well have been forever.

These days, at Mets World Headquarters and its mobile locations across the continent, seven innings is almost unheard of. Hell, we hadn’t heard of it all year. But through Lucchesi-enabled ears, we heard an outing that lasted longer than anybody else’s: not just seven bullpen-preserving innings and nine strikeouts, but no runs allowed. None! Who does that in these parts anymore? Not the suspended Max Scherzer. Not the mending Justin Verlander. Not anybody else who’s taken the ball to date. They’ve all handed the ball back to the manager no later than the end of the sixth inning. Joey sorted his pitches (he’s not just for churves anymore) and befuddled the Giants. It bears repeating that they didn’t score in any of the seven innings Lucchesi was on the mound being “sick, man,” as the lefty hurler put it, availing himself of one of those phrases that means the opposite of what you might infer.

You’d think a pitcher who had to battle injury to pitch again in the majors might want to avoid any hint that he’s not feeling his best.

Nevertheless, all was well with Joey and his pitching in the Mets’ 7-0 win. Take it from his first baseman, who affirmed Lucchesi was “straight carving,” bringing “funk” and “uniqueness” to his delivery. Pete Alonso ought to know. He’s been carving up pitching himself of late, even more than when he began to bring both the funk and the noise to the Met record book four seasons ago.

The uniqueness of Pete’s achievements seem to speak for themselves. Following his wallop to dead center off Anthony DeScalafani in the fifth, Alonso is at 10 home runs after 21 games, reaching double-digits nine days before the 30th of April. Few sluggers do that. Met sluggers, rare birds and Bears that they are, have never done that. In the long view, Pete is up to 156 home runs in a career that by conventional standards isn’t much removed from its early stages. (Or maybe it just seems that way to me.)

When Pete homered the evening before, for No. 155, it rearranged a Met list that’s had one constant since approximately forever, even longer than Swan had to wait between wins from 1974 to 1975. Alonso’s second-most recent dinger placed him alone in fifth place on the all-time Mets home run list. Keep Pete a Met long enough, he’ll be alone in first, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves. It’s enough to note who Pete is ahead of right now.

On September 4, 1976, it was a big deal that Craig Swan’s teammate Dave Kingman had homered. Not an unusual deal in the vast sweep of Kingman’s career, which would go on to encompass 442 home runs, but this one was big for a singular reason at the moment it was hit. Kingman had been out with torn ligaments in his left thumb between July 19 and August 27. When he went on the DL, Sky King (the nickname Dave preferred over Kong) led the world in home runs with 32. The National League title was in the bag, just waiting for a twist-tie. The National League mark for one season, 56 — Hack Wilson’s total in 1930 — was legitimately in sight. The Mets weren’t going anywhere in 1976, but there appeared to be no limit for Sky.

Then Dave dives for a fly ball, and the thumb gets hurt, and you can kiss Hack Wilson goodbye. More disturbing is the twist-tie is no longer firmly in our grasp, either. While Kingman is sidelined for the back end of July and the bulk of August, Mike Schmidt makes up an eight-tater deficit and ties Dave, 32-32. Our first National League home run crown, out of the bag and rolling around on the table, is truly up for grabs.

On Saturday, September 4, a game with such powerful implications that a distracted Bar Mitzvah guest slips away to a pay phone for updates via 976-1313 (I had to let the Bar Mitzvah boy, a fellow Mets fan, know what was going on at Shea), sees Schmidt grab the lead, 33-32, when he homers off Nino Espinosa in the sixth inning. But then, in the seventh, Kingman evens the score in the only race that matters, belting his 33rd home run, off Ron Schueler. The Mets win the game, which is swell, but more importantly, considering the 14½ lengths the first-place Phils have on the third-place Mets, Dave is tied for the top in his category.

Little remarked upon if mentioned at all that afternoon was who else Dave Kingman tied when he homered. No. 33 on the year was also No. 69 since he’d been a Met. It had been seven years since 69 embedded itself in our consciousness as the nicest number in the Mets’ numerical lexicon, but there was more to it than world championship echoes. Ron Swoboda, you see, had hit 69 home runs in his Met career. That tidy sum, through September 3, 1976, amounted to the fifth-most in Mets history. The Mets were in their fifteenth season, having spent most of their time copiously avoiding the other side of the fence when at bat. Ed Kranepool had only a month earlier become the first player to hit 100 home runs as a Met. Ed Kranepool was in his fifteenth season, too.

So you had Krane, you had Cleon Jones (93), you had Tommie Agee (82), you had John Milner (80), and you had Swoboda. That was the Top Five Mets Home Run chart.

Then, on September 4, 1976, you had Kingman politely asking Swoboda to scooch over and share fifth place. Two days after that, at Wrigley Field, Dave decided he wasn’t crazy about sharing and took fifth for himself, launching his 34th homer of the season and the 70th of his Met career. This was your up-to-the-minute franchise home run ranking:

Ed Kranepool 100

Cleon Jones 93

Tommie Agee 82

John Milner 80

Dave Kingman 70

Dave was fifth all by himself, and would remain one of the Top Five Mets sluggers of all time in perpetuity.

Perpetuity covered his departure amid the Midnight Massacre, by which time Kingman — who was edged out by Schmidt for the 1976 crown, 38-37 — had totaled 82 Met home runs; his boom-and-bust exploits as a Padre, an Angel, a Yankee and a Cub following the transactions of June 15, 1977; the return of Sky King in 1981 and the 22 home runs he clouted that strike-shortened season; 1982, when Dave not only tied his own single-season club record of 37, but finally became the first Met to lead the league in a triple-crown category; the 13 he hit in 1983 before Keith Hernandez’s presence made first baseman Dave totally superfluous at Shea; his next act as the A’s DH; the rise of Darryl Strawberry; the emergence of Howard Johnson; the acquisition of Mike Piazza; the sustained if truncated excellence of David Wright; and everything until this current Met trip to California.

Because during this current Met trip to California, Dave Kingman stopped being, statistically speaking, one of the Top Five Mets sluggers of all time and stopped owning one of the five highest Mets career home run totals. When the trip started, that list looked this:

Darryl Strawberry 252

David Wright 242

Mike Piazza 220

Howard Johnson 192

Dave Kingman 154

Perpetuity expired on the West Coast in April of 2023. Pete Alonso pushed it toward extinction in Oakland, where Dave Kingman had revived his power stroke once the Mets ate his contract and let him go to whoever wanted him. The 1984 A’s, somewhere between Billy Ball and the Bash Brothers, picked him up, and Kingman commenced to do the only thing anybody ever really expected of him. In three seasons almost exclusively designated hitting, Dave bashed exactly a hundred homers, or as many as Kranepool collected to lead the Mets as a franchise over an approximate fourteen-year span. I thought it would be appropriate if Pete could pass him in L.A., where Dave enjoyed his most legendary night as a Met, socking three homers and driving in eight runs on a Friday night in 1976, but the Polar Bear settled for several hits of the non-homer variety against the Dodgers (unlike Dave, Pete often reaches base without circling them). Instead, Alonso waited for the series in San Francisco, facing the team with whom Kingman got his start in 1971, the team that sold him to the Mets in 1975. No. 155 came in the series opener. No. 156 came the next night, Lucchesi’s big one. No. 157 and beyond are welcome to arrive with whatever haste Pete Alonso can arrange. Whoever’s pitching will definitely appreciate the support.

Now, for the first time in nearly 47 years, when you list the five leading home run hitters in Mets history…

Darryl Strawberry 252

David Wright 242

Mike Piazza 220

Howard Johnson 192

Pete Alonso 156 and blessedly counting

…you don’t see Dave Kingman’s name. But Mets fans who saw him go deep still see that swing. When it connected, the ball soared roughly as high as those United Airlines planes whose roominess the 6-foot-6 Dave smilingly extolled in commercials when he began gaining fame for scaling the heights of the Met home run chart. Kingman didn’t always present a persona one would describe as advertiser-friendly or media-friendly or, at infamous intervals of his professional life, minimally friendly in general, but the way he piled up home runs won fans and influenced little leaguers. You swung for the fences as a kid in and around New York in the latter half of the 1970s, you were accused of trying to be Dave Kingman. When you succeeded, you took it as a compliment.

Few succeeded at what Kingman was best at like Kingman, which is to say the Mets got him to hit home runs and he hit home runs. Boy, did he hit home runs. The number went unmatched until Darryl eclipsed 154 in 1988, and it went unsurpassed by fewer than a literal handful until Alonso came along and became unstoppable. Yet giving way on the all-time home run list and not being among the Top Five any longer doesn’t detract from what Dave did, or could do, or had you sure he would do as a Met. I watched the Mets play games at or from Shea Stadium from 1969 through 2008. Dave Kingman was definitely the first Met who didn’t shock me by hitting a home run there, maybe the only Met who didn’t intrinsically surprise me by hitting a home run there.

There’d be some gifted hitters who I understood were capable of homering at Shea, and a select group who did it relatively often, but Kingman was the only one who I expected, all things being equal, to hit one out. Maybe Straw or Piazza with a game on the line, given their proclivity for meshing power with drama, but in terms of simply “he’s gonna hit a home run here” captivating my thought process in a random inning on a random night, that was Dave Kingman above everybody else. I’d look at him through that prism on the road, too, but Shea was such a not home run hitters’ park. Every clip I see of a Met homering at Shea, I’m still amazed that ball gets out of there. Except when Kingman swings and makes contact.

Pete Alonso plays his home games in a ballpark and in an era where home runs don’t seem that surprising. I don’t take the frequency with which he hits them for granted by any means, although I suppose at this point, you could be forgiven for almost counting on a long ball now and then. It’s not all Pete brings to the plate. Alonso is more of an all-around hitter than Kingman ever was as a Met, and now he has more home runs than Kingman ever had as a Met. Knock wood, he’ll have more home runs than anybody ever had as a Met, and we won’t have to wait forever for them to take off, no matter how long it takes them to land.

But I swear: there was only one Dave Kingman. I mean that as a compliment.

by Jason Fry on 21 April 2023 8:54 am Loyalty is strange.

Not in the sense of feeling it for men decades younger than me, men I think I know but don’t in any way that matters. Though that’s certainly strange too.

No, I was thinking about it in the context of how that loyalty gets transferred when those young men change — sometimes willingly and not — out of one set of faintly ridiculous pajamas and into a new set. They keep doing their jobs and behaving more or less as they did a little while ago, only now that loyalty has been transferred to new young men about whom I know a whole lot less.

I have a few hours invested in the likes of Kodai Senga, John Curtiss and Jeff Brigham. I gave many, many more hours of my life to cheering on Wilmer Flores, Michael Conforto and J.D. Davis. (We’ll leave poor star-crossed Darin Ruf out of this conversation.)

Flores literally grew up as a Met minor leaguer, learning English by watching “Friends” re-runs; maintained his dignity while being asked to play positions he had no business playing; wept when he learned from cellphone-wielding fans that he’d been traded; and then authored one of the signature moments of the last decade when he followed his walkoff homer against the Nats with a heartfelt pull at the METS across his chest.

I watched Conforto as a Cyclone down on Coney Island, then as a Met with my heart in my throat in the World Series because I remembered him being in single A just moments earlier. He was my favorite player for several years, the guy I kept predicting greatness for and whose cause I espoused with ardent fury when the Mets mishandled him. That greatness proved more theoretical than realized, derailed by bad luck and injuries, but I still needed a moment when I learned he was officially no longer ours.

Davis also never quite ignited as a Met, but provided seemingly endless moments of entertainment and surrealism — heckling opponents in his reedy, not-made-for-heckling voice, all but urging Met fans to storm the Bastille after a walkoff, and offering general merriment as Pete Alonso‘s sidekick, Sun Bear to the Polar Bear. (Though as Greg noted, Solar Bear was right there.) Even his nickname was the stuff of amused double takes — Jonathan Davis’s middle name is Gregory.

By comparison:

Senga comes from Japan, seems like a good dude, and throws that ghost fork.

Curtiss signed with us and spent a year waiting for his elbow to knit, during which there’s no way I could have picked him out of a police lineup.

Brigham was a Marlin and shares his name with a New England chain that’s kind of a JV Friendly’s.

And yet as the Mets and Giants battled it out, I was rooting for Senga, Curtiss and Brigham to succeed and — after initial, heartfelt applause — hoping Flores, Conforto and Davis would fail. On the face of it that doesn’t make a lick of sense.

Such contradictions are easier ruminating upon when your team is comfortably ahead, which the Mets were … twice. They built both leads using a dynamic that it was nice to see them tap back into, spending their first rotation of ABs carefully studying a pitcher and then ambushing him in the second go-round.

Sean Manaea was the first victim, undone in the fourth by two-run homers from Alonso and Eduardo Escobar and a run-scoring double from Brandon Nimmo, hot enough that objects near him are suddenly aflame.

Senga repaid his teammates’ generosity by having one of those seemingly inexplicable innings that used to plague Al Leiter, where both principal and perplexed fans are left wondering why said principal has apparently forgotten how to pitch. Blake Sabol and LaMonte Wade Jr. homered, Mike Yastrzemski singled in a third run, and a Senga wild pitch brought home Conforto, sliding across the plate on his now cream-colored belly.

Some harm, no foul: After sizing up newcomer Tristan Beck for a bit the Mets blitzed him, running up a brand-new five-run advantage. At which point your chronicler, who is Officially Too Old for West Coast Trips, bid them and the land of the awake adieu and checking the score once rebooted with sleep and coffee. Turns out they won, with the guys I barely know in gray and orange and blue beating the guys I know well who now wear the wrong unis. And since I am mildly alert for the first morning in quite a while, feels like I won too.

by Greg Prince on 20 April 2023 10:33 am The man used sweat and rosin, he said. He said it a lot. He repeated it enough so that I believed him, which doesn’t always work. The pitcher doth protest too much, methinks might be applicable here, except the pitcher pitches for the Mets and Met-think is how methinks. Besides, this is Max Scherzer in his sixteenth season, the majority of those spent as an ace of aces. He’s suddenly sticking substance he’s not supposed to all over his pitching hand after several starts already this season when this didn’t seem to be an issue?

Pitchers will look for an edge, particularly late in their career, maybe if they haven’t been as sharp as all get-out, especially, you’d think, if the pitcher was coping with discomfort that had pushed back his spot in the rotation. Yet I’m not buying any of that as a likely explanation for whatever the umpires decided was awry in L.A. Wednesday. I don’t know that Max Scherzer is the kindest, bravest, warmest, most wonderful human being I’ve ever watched pitch in my life, but I do sense he is not, as he put it, enough of “an absolute idiot” to get checked for stickiness in the first place; be told to take care of it; take care of it as MLB officials inspected him taking care of it; and then return to the field with gobs of verboten goo.

Yet the man was ejected from the dual shutout he was engaging in with Noah Syndergaard, speaking of storylines shunted to the rear by umpire Phil Cuzzi, self-appointed crusader for clean living among pitchers. Max, who’d been missing from action for nine days, was rolling along after wriggling from trouble in the first inning. The second and third were so clean that you’d think they were scrubbed with alcohol. Max never saw the mound in the fourth, having been asked to remove himself from his place of business. When he’ll return is up for grabs in light of this sticky-wicket contretemps and the ten-game suspension it’s supposed to automatically trigger.

The Mets continued to play their game against the Dodgers on Wednesday afternoon, downgrading our half of the glamour of Scherzer v. Syndergaard to Yacabonis, et al…, not quite the same thing, but somehow efficient enough. Thor, as we used to call the opposing pitcher, wasn’t his old bowl of doom self in terms of velocity, but the wandering Norseman was effective if not evocative of the days when we hung on his every golden lock. Keeping his own once-famous ass out of the jackpot, Syndergaard gave up only a pair of runs in six innings, both scoring when Brandon Nimmo took him deep with Francisco Alvarez on first base. My first thought was how appropriate it was that Brandon should homer off Noah in that they used to be super buddy-buddy. My second thought was, wait, that was Conforto, not Nimmo.

It was all Nimmo, eventually. Brandon went 5-for-5 against Syndergaard and succeeding Dodger arms. Meanwhile, the post-Max pack, led for two-and-two-thirds by Jimmy the Yak, picked up the Scherzerless slack. A potential ace tour de force became a bullpen game, and for the last six innings, Jimmy Yacabonis plus Jeff Brigham, Drew Smith, David Robertson and Adam Ottavino did the best thing relief pitchers can do: they got the job done. Nimmo’s exploits worked in harmony with Mark Canha (two RBIs) and Tommy Pham (key sac fly) to bolster Max’s supporting cast en route to a 5-3 rubber game victory. Afterward, when Scherzer paused from claiming perfectly permissible “sweat and rosin” long enough to answer a question about how well Yacabonis pitched in his place on no notice, Max smiled and said the long reliever definitely deserved a steak dinner, presumably on him.

That’s really nice, assuming Max washes his hands before passing the potatoes.

The Mets are five games over .500, a level they never approached 60 years ago, but 1963 was its own kind of fascinating Mets year, as you’ll hear all about in the It Happens in Threes segment on the new episode of National League Town.

|

|