The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 12 August 2024 3:46 pm Adequacy thy names are Quintana, Manaea, Severino, Blackburn, and Peterson. We’ve had some really good games from the starting pitchers who compose our rotation this season. Some not so good games, too. Some days you wish we had the Christian Scott who looked so promising in his debut or the Kodai Senga who was on point for five-plus innings before an injury subtracted him from our plans.

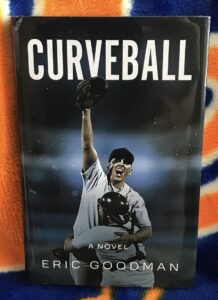

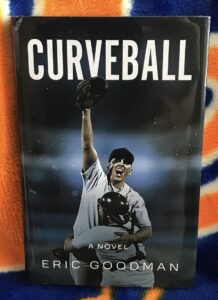

For about a week, the starting pitcher I wanted to see on our mound more than any other was Jess Singer, coinciding with the week or so I was wrapped up in reading Curveball, the new Metcentric novel by Eric Goodman. I imagine it’s a book more about the human condition than baseball, the way I’m always being told that baseball movies aren’t baseball movies so much as they’re this genre or that. But we’re Mets fans. Make two of the three main characters Mets and build the story around a Mets season, it’s a book about the Metsian condition.

I’m gonna guess Goodman wouldn’t mind that assessment, for he, too, is a Mets fan. Takes one to write one like this. The author, in a note introducing his work, let me know he’s been rooting for this team since 1962. He also first wrote about a Singer pitching for the Mets in 1991’s In Days of Awe. The pitcher at that juncture in Mets history was the great Joe Singer. We could have used a great pitcher right around then. Goodman decided some three decades hence that we needed a sequel. Thus, Jess, son of Joe. Two Singers. Two pitchers. Two Mets. Loads of talent…including Eric Goodman in bringing this pair to us. I’m gonna guess Goodman wouldn’t mind that assessment, for he, too, is a Mets fan. Takes one to write one like this. The author, in a note introducing his work, let me know he’s been rooting for this team since 1962. He also first wrote about a Singer pitching for the Mets in 1991’s In Days of Awe. The pitcher at that juncture in Mets history was the great Joe Singer. We could have used a great pitcher right around then. Goodman decided some three decades hence that we needed a sequel. Thus, Jess, son of Joe. Two Singers. Two pitchers. Two Mets. Loads of talent…including Eric Goodman in bringing this pair to us.

A couple of grabbers to get your attention.

1) Joe Singer was known in his heyday as Jewish Joe Singer. The nickname for Jess is Two-J’s, because Jack Singer — the irrepressible zayde or grandfather in this mishpacha and our third main character — proudly declared the boy was as “big as two fucking Jews”. The aura of Sandy Koufax exists in the world of Curveball, and the Singers are the closest thing we’ve seen to the, uh, sainted Jewish lefty since the Dodger southpaw took off Yom Kippur. As an homage, Joe and Jess were and are No. 32 on your overpriced scorecard.

2) The existence of Koufax (not to mention Ken Holtzman) within Baseball-Reference means a star Jewish pitcher, while unusual, isn’t unprecedented. But an openly gay pitcher in the major leagues is a different story. As of the present reality, we haven’t had any MLB players go to work making no secret of their non-heterosexual orientation. When Curveball begins, that’s the situation as well. The percolating question as one gets into the book is, will this be the situation by the last page? Let’s just say Jess Singer is harboring a secret and much of the tension revolves around his deciding if he’ll make it common knowledge.

Other issues, including literal life and death, permeate Curveball, and they deserve the reader’s consideration, but let’s not stray from the Metsiness of all this. The Mets of Jess Singer are a recognizable contemporary replica of what we’ve rooted for these past few years. There’s an owner you might mistake for Steve Cohen; a club president who seems to resemble Sandy Alderson; and players referred to as Pete, Squirrel, Nimms and the superstar shortstop. Goodman didn’t exactly drop Jess Singer onto the early-2020s Mets, but he knows his way around Citi Field physically and spiritually.

Each of the three Singer men presents his own emotional handful to those who care for them, which as the novel went on, included me. I raised my arms at least twice in triumph as I devoured their tale, and only once directly relating to the baseball action Goodman created. In the parlance of sports talk radio, I’m not a fiction guy, but my affection for this book was very real. In case you can’t make me out over PitchCom, I’ll put the signal in plain sight where any Astro can interpret it: don’t leave Goodman’s Curveball off the plate.

by Jason Fry on 11 August 2024 10:50 pm I generally keep track of what the Mets are doing even if I’m away, sneaking looks at MLB.tv, popping an airpod into an ear, or at least letting GameDay do its pantomime thing in my lap.

But combining a trip to Iceland with the Mets’ Road Trip from Hell was a perfect recipe for being well and truly out of pocket. With the additional time change, the games started after I was asleep and concluded before I was awake. I heard Paul Blackburn‘s debut against the Angels, with the last out recorded shortly before boarding a midnight flight (oh, things looked so promising then). And I caught the first couple of innings of the middle game against the Mariners because I couldn’t sleep.

Between them, nada: I’d look at my phone over skyr and coffee in the Icelandic morning and try to make sense of things that had already transpired. There’s always a funny moment when you look at the score of a baseball game and your brain needs half a second to parse it: Oh, the bigger number’s here and the smaller number’s there, that’s good/bad, and now that I’ve got it straight, let’s figure out exactly how that happened.

What this sequence of revelations told me was, above all else, frustrating: We can’t win a series against the Angels, really? Figured they’d drop that dumb makeup game in St. Louis, so whew. OK, nice bounceback series in Colorado. And then the buzzsaw of the Mariners’ starting staff and the bats returning to slumber.

I got to watch the Mets uninterrupted for the first time in nine days on Sunday evening, and for a while that even seemed like a good idea. Luis Castillo was dealing, but so was Luis Severino, with the shadows of a Seattle afternoon game turning an already tough job for hitters on both teams into the stuff of borderline farce. But then a taut, tight duel turned when the Mets let in a run on a little infield hit that Francisco Lindor‘s best effort couldn’t quite convert into an inning-ending out, Severino left a changeup in Cal Raleigh‘s wheelhouse, and suddenly the Mets were down 4-0.

Down 4-0, and it was about to get a whole lot worse. Jeff McNeil homered to keep the Mets from being shut out all three times in Seattle, but that was all that went right. In the sixth the annoying ESPN crew ooh’ed and ahh’ed over a bald eagle soaring above Seattle; a moment later I was fervently wishing this majestic bird would swoop down and carry Ryne Stanek off to Syracuse or the Ross Ice Shelf or some other place where I’d never have to see him again. Soon after that I was imagining other eagles dropping by to remove Adam Ottavino and Danny Young from view. Alas, those relievers stayed around to do unhelpful things until the Mets were mercifully allowed to slink back to New York, grateful the whole thing is finally behind them.

Except it isn’t. The Mets apparently pissed someone off in the MLB scheduling department, as they’ll be heading back to the West Coast in 11 days.

Maybe I’ll go back to Iceland and miss that one too.

by Greg Prince on 11 August 2024 2:22 pm The last shreds of Interleague mystery are falling away this season. We’re in Seattle for the first time since 2017, which hints at the randomness of the way NL vs AL used to be scheduled. When this gimmick was introduced in 1997, We in the NL East played They in the AL East every year for five years. Then the AL Central and AL West got involved in our lives on an alternating-season basis, though not always each team, and it didn’t necessarily elbow aside oddball intrusions. In 2007, for example, our Interleague slate encompassed the A’s, the Tigers, the Twins and the Yankees. In 2010, it was Baltimore, Cleveland, Detroit and the crosstown rivals. A year later, we were still getting paired with the Tigers, but also the A’s and Rangers (and Yankees, always the Yankees). I couldn’t detect patterns then and I can’t discern one now.

When the Astros departed the NL in 2013, it was supposed to become more predictable. We’d play one division every three years, and we’d switch off the sites accordingly…and the business with the team in the same city would remain annual. Yet circumstances still managed to ruffle the smoothness. We went fifteen years between hosting the team formerly known as the Indians. It took seventeen seasons to get the White Sox to Flushing. COVID certainly didn’t help. We’ve played three games in Buffalo (2020) since we were last in Toronto (2018), but we’ll be in Toronto in September. The last time we were on the South Side of Chicago (2019), the big story was we didn’t trade Noah Syndergaard and the jaw-droppingest home run (426 feet, 109.2 MPH) was launched by Michael Conforto. But we’ll be at whatever New Comiskey insists on calling itself in late August.

Conforto’s homecoming to Washington state was a prime storyline the last time the Mets visited Seattle, just over seven years ago, which might as well be seventy. The streak of the moment was Jacob deGrom — who was Jacob deGrom, to be sure, yet was still a season away from becoming Jacob deGrom — sitting on eight wins in eight starts. His streak got snapped in Seattle, and it would rarely again seem like deGrom’s excellent pitching was capable of producing a personal W. This was also the last weekend before the Mets did what most everybody was waiting on them to do and called up Amed Rosario. Remember when he was the personification of the future? That Mariners series was our first look at Edwin Diaz, who we might have heard was having an excellent season three time zones and another league away. We had just traded Lucas Duda for a minor league reliever named Drew Smith. We were about to trade a whole bunch of familiar names for the less familiar kind (none of whom attained a Met track record on the level of Smith’s, which, to be honest, isn’t all that voluminous). On the personal front, I had just said goodbye to one my beloved cats — RIP Hozzie, 2002-2017 — which might explain why the Mets’ trek to Seattle stays with me a little more than most fleeting Interleague entanglements.

Prior to the latest shutout at the hands of the Mariners, I concluded there is no organic reason I should particularly care about the Mets playing them ever in the regular season. There could have been. In October of 2000, the Mariners were in the ALCS when we were in the NLCS. A Mets-Mariners World Series would resonate to this day any time the two franchises crossed paths. The Mets will play the A’s and Orioles on the upcoming homestand. Echoes of 1973 and 1969, respectively, will drown out remembering that time we played them in 2010 or whenever.

In my unfrozen caveman heart, the World Series is the only proper setting for a National League team to play an American League team in a game with stakes. That’s organic. All other such meetings should be confined to Spring Training and exhibitions that fall out of the sky. The deluge of Interleague play ensures every World Series matchup of the past gets a rematch every year. There’s little charming about that when you can count on its arrival like National Potato Chip Day, but at least it’s something. Before it all got codified, those encores got your attention. Mets-Orioles. Mets-A’s. Mets-Red Sox. (Mets-Red Sox also qualified as an exhibition that fell out of the sky when they scheduled a charity home-and-home in September 1986 and May 1987 without any idea that they’d be getting together for stakes during the October in between.)

Mets-Yankees was better when it was the Mayor’s Trophy Game. Mets-Royals post-2015 lost its juice by 2019. Mets-Royals could have just as easily been Mets-Blue Jays (a World Series we would have won, I take it on faith). Mets-Orioles and Mets-Red Sox could have been Mets-Twins and Mets-Angels had the playoffs in the other league had different outcomes those years, but the two World Series in question worked out, so why mess with a good thing? We’d look at Mets-Tigers regular-season encounters differently had we done our part in the 2006 NLCS.

Had the 2000 Mariners of John Olerud, Rickey Henderson, Alex Rodriguez and whoever else was there before Ichiro Suzuki done their job in the ALCS and prevented a Subway Series, this weekend would be embellished by video clips of that unforgettable October twenty-four years ago when the long transcontinental flights were worth it, because the journey we were on allowed us to set the stage for (if we’d won in four or five) or bring home (if it had gone six or seven) our third world championship trophy. Or maybe it would have gone the other way, and we’d still sneer at the sight of anything smacking of Seattle.

Instead, it’s just another date with another opponent on another overstuffed schedule. Next time we play “at Mariners,” it will be in two years. Same deal with the White Sox and Blue Jays and every AL club we didn’t host this year. We’ll host them next year, just like we hosted them last year. Those we visited last year we’ll visit next year. And the nicest part of all, Val, I look just like you.

by Greg Prince on 10 August 2024 1:03 pm A pretty good baseball team soundly defeated another pretty good baseball team on Friday night in a corner of the country far from the one where I struggled to stay awake to witness the entirety of the contest. By drifting off as I tend to when baseball games begin inconveniently late where I am, I missed a couple of runs scoring, which was OK, since none of the runs scored in any inning were scored by the pretty good team I was rooting for. My team’s still pretty good even if it didn’t win. These things happen, just like my in-game naps. Maybe it will work out better tonight. I’ll probably fall asleep for at least part of it.

My team needs to play games earlier, and, if possible, only the games it wins.

by Greg Prince on 9 August 2024 8:59 am Oh, look — the three National League Wild Card teams at the moment are the San Diego Padres, the Arizona Diamondbacks and the New York Mets, while the three National League division leaders remain the Philadelphia Phillies, the Los Angeles Dodgers and the Milwaukee Brewers.

Who is missing from this “if the playoffs began today…” picture? Correct! It’s the Atlanta Braves!

The playoffs don’t begin today, and playoff positioning is more fluid than sweet tea on a scorcher of a Saturday amid the red clay of Georgia, but let’s enjoy Atlanta’s exclusion from postseason tournament calculations, if only for twenty-four hours.

“If the playoffs began right now, the Braves wouldn’t be in them,” I informed my wife after the Mets finished off the Rockies, 9-1, shortly before the six o’clock news Thursday evening.

“What a shame,” she deadpanned.

Stephanie is not exactly caught up in the daily fluctuations of the standings, but she can sort out the villains in our narrative without having to ask which one merits our contempt most. Eleven Octobers ago, first thing in the morning, I updated her on the postseason in progress, letting her know that the night before the Dodgers had eliminated the Braves. I expected no more than “that’s nice.”

Instead, she delivered, “See ya, Braves!”

Yes, yes, a thousand times yes. And that (2013) was a postseason we as Mets fans were merely watching, not one our team was trying to slug its way into. We didn’t have Pete Alonso going extremely deep twice as we did in our Coors Field finale. We didn’t have Mark Vientos chipping in a homer. We didn’t empty a gunny sack loaded with doubles as we did on the Rockies in the very first inning. We didn’t have Tyrone Taylor flying to and fro to track down balls before they could become mile-high trouble. We didn’t have David Peterson enjoying a gratifying Colorado homecoming. Thursday we did, and now we have floated ahead of our more-or-less archrivals for something of substance, keeping them away from what they want in the process. We have a half-game lead on the Braves for the third Wild Card spot with 47 games to go, which isn’t a prize they embroider t-shirts over, but with 47 games to go, the best place to see the Braves is behind us.

Chances are we’ll see the Braves in our nightmares as the National League derby continues. It’s too much to ask they plummet through the contending tier that lately encompasses the Cardinals, the Pirates and the Giants and find themselves sliding down toward, well, the Rockies. In fact, the Braves get to play the Rockies this weekend, while we travel — we always travel — to Seattle to take on a bona fide contender in the other league.

Can’t get too comfortable in the second week of August over positioning for October. But I’ll be damned if I’m not going to enjoy the current reality for however long it’s current.

by Greg Prince on 8 August 2024 12:22 pm Aw, I missed a triple? I did. I nodded off in the seventh, shortly after Jose Butto came on in relief of Paul Blackburn, the score at Coors Field knotted at two. That’ll happen with any game that starts any time after 7:10 where I sit; then stretch out; then close my eyes for just a little bit, I’m sure. Extended day, abbreviated night. But I did stir in the bottom of the ninth. Things had changed, per the SNY graphics. The Mets were up, 5-2. Wait, now it’s 5-3, but Gary Cohen didn’t seem concerned. The Mets, he said, would gladly trade a run for an out here. How many Rockies are on base, anyway? Why is Edwin Diaz giving up a run and why is this considered a fair exchange? While I was in the process of discerning there were two out, Edwin finished striking out Charlie Blackmon. “And the ballgame is over!”

I didn’t have the energy to stay awake for the postgame show, but I reached for my phone, clicked on the At Bat app, and satisfied my curiosity at how a game that had been tied for so long went the Mets’ way. Francisco Alvarez had tripled with one out in the top of the ninth — and I missed it. Triples are so great, yet so rare. Maybe that’s why they’re so great. And a catcher triple! Francisco has hit two this year, practically leading the team (Tyrone Taylor has three). Fralvarez, as I sometimes address him from the couch, isn’t our catcher of the present and future for his tripling. Luis Torrens is an ace backup, though he has yet to triple as a Met. Nobody really expects a triple to begin with. Other than Lance Johnson for one year and Jose Reyes for a bunch, “somebody needs to triple here” never passes through your mind. They weren’t catchers.

When I think of a catcher hitting a triple, I think of Gary Carter tripling in Game Four of the 1988 NLCS. Sixth inning. Kid’s three-bagger sends Kevin McReynolds home from second, putting the Mets further up on the Dodgers, 4-2. Nobody’s out. We’re gonna blow this game open, we’re gonna be one game from the World Series, we’re gonna have our hands full with Oakland, but I know it’s coming. Instead, Carter is left on third and another catcher for the other team hits a four-bagger. To me, our dynasty didn’t turn on Mike Scoscia’s home run. It withered when the Mets didn’t take advantage of a catcher triple. (And I stopped making World Series plans in advance of pennant-clinchings.)

Yet I still relish a catcher triple like few other hits by few other players. Jerry Grote tripled nineteen times as a Met, which ties him for nineteenth among all Mets in triples. I wouldn’t have guessed that. John Stearns is part of a six-way tie for forty-fifth place in triples with ten. I would have figured Stearns, who could run, had more than Grote. Turns out he has as many as, among others, speedy Roger Cedeño and Wednesday night’s RBI hero Francisco Lindor. It was Lindor who delivered the key single — a common but essential form of base hit — to put the Mets ahead in the same ninth that Alvarez did three times as much as single. Fralvarez was shown mercy and to the bench after tripling. You wear the tools of ignorance for eight innings and then chug 270 feet. Harrison Bader pinch-ran. Ben Gamel (still on the team, apparently) and Tyrone Taylor walked. Then Lindor came through to make it 4-2. One out later, Jesse Winker, who to this point in his Met tenure hadn’t been any more a factor in any day’s Met offense than Ben Gamel, singled for insurance. A three-run lead while I slept. A three-run lead trimmed to two as I briefly eschewed sleep. A two-run lead to put me pleasantly back under a moment or two later.

I would have liked to have seen that triple as it happened, but getting the gist did just fine.

by Greg Prince on 7 August 2024 12:39 pm The Chicago White Sox ended their 21-game losing streak Tuesday night, preventing them from owning outright the worst skid in American League history and momentarily pausing their pursuit of hallowed infamy that for 62 years has belonged to us. But as players and managers usually say following a loss rather than a win, it was just one game. Having gone 1-21 in their previous 22 contests, 2024 Sox have plunged to a record of 28-88 through 116 games, or two games behind the 1962 Mets at the same juncture of their year buried in the cellar like nobody gets buried in the cellar.

The Original Mets are the Original Mets for a reason. Every few years, some crappy team is billed as a challenger to 40-120. Lately, with tanking in vogue, it’s every year. The 2023 A’s were projected as on a 1962 Mets pace. The 2022 Reds were inspiring unflattering comparisons. But it’s hard to stay historically awful, not to mention endlessly fascinating while being so. All it takes is a spurt of competence, and suddenly a team of professionals begins to play just professionally enough to waft toward mere mediocrity. The only ballclub that maintained a legitimate shot at something worse than 40-120 since 40-120 was Detroit in 2003.

Oh, they tried. After 156 games, those Tigers were 38-118, the product of some really clutch September losing (ten in a row, fourteen of fifteen) that seemed to negate the effects of an ill-timed three-game winning streak just after Labor Day. The 1962 Mets after the same number of games completed were 39-117. The Motor City Kitties of four decades-and-change later simply needed to not suddenly remember how to roar over their final six games and they would share a piece of whatever it is that a team that loses that often winds up with.

A word on 40-120. The National League had begun playing a 162-game schedule in 1962. Your whole life as a Mets fan, you’ve seen 40-120. You might wonder whatever happened to those other two games. I certainly did (that’s the way I am). The first of them is discernible in the books as a tie. The other requires a touch of digging to discover.

(Rabbit hole dive incoming.)

The two tilts that at first glance escape existence at were both to be between Casey Stengel’s babes in the woods and their expansion cousins in Houston. The tie was played at outdoor Colt Stadium, the franchise’s pre-Astrodome home, on September 9, but it wasn’t as simple as deciding it was a tie on September 9, Mets and Colts, get on with your lives. Yes, the score was tied at seven and no more baseball was played that Sunday. Well, you might think, into each life a little rain must fall.

You’d think. It’s what I thought for years. And, as burrowing into newspapers.com reveals, a little rain did fall, but rain wasn’t really the reason the 1962 Mets went 40-120 rather than 40-122. No, a curfew was the cause of the tie. Oh, you might infer, the Mets and Colt .45s were swingin’ all night long on a Sunday, like that time the Mets and Astros stared each other down under the Dome over 24 innings on a weeknight in 1968, but this was the Lord’s day, and 24 innings was obviously too long for those bible-thumbers in the state legislature to cotton, huh?

It wasn’t that. This was a day game sans extra innings, though the Colts insisted on changing the start time from 2:30 PM to 4 o’clock, which itself seems like no big deal; afternoons, then as now, could get hot in Texas, and every little bit of shadow cooling things off should be appreciated. Except Dick Young, before he turned heel for the ages, explained the switch was made “in order to draw a big crowd” for the 35-108 Mets visiting the 55-87 Colt .45s (this after a day-night doubleheader on Saturday didn’t exactly have Houstonians busting down gates for the matinee or nightcap). The attendance on Sunday, Young wryly noted in the News, was 3,630.

Because the game started at four, and because the Mets were determined to stick to their getaway plan of taking off from Houston as slated (anything to get away from those Volkswagen-sized mosquitoes Ralph Kiner relished recalling once Colt Stadium was long demolished), a time limit was set in advance. No baseball after 7 PM. These were the days when ballgames were played fast, so no problem fitting in nine innings, right?

Since when does any story involving the 1962 Mets come without a problem? Young: “Three hours were allowed to play this one here — and you just know the Mets don’t finish games within three hours.” The box score shows the Mets and Colts required 2:49 to reach a 7-7 impasse, not helped along by a dozen minutes of “shower delays,” per Young.

Flight time was nigh, so the players stopped playing, but it wasn’t conclusively inconclusive. The National League office ruled that these boys had to get this game done when the teams got together in New York September 18-20. Sounded like a plan. A borderline insane plan, but a plan, nonetheless.

Except for rain, and not just shower delays. The Mets and Colt .45s got rained on a lot in 1962, especially in New York. They were postponed once in their very first Manhattan series, in April. The game was added to a Polo Grounds set in June, except it rained again, so another makeup was inserted into the final Colt trek to the Big Apple. The clubs were looking at a doubleheader on a Tuesday; a doubleheader on a Wednesday; and a single game on a Thursday…to be preceded by the completion of that all-important 7-7 suspended affair from what would be, by then, two Sundays earlier.

Whoever or Whatever controls the atmosphere decided people seeking out the Mets and Colt .45s in September of 1962 needed to be saved from themselves. The Tuesday doubleheader was played; two Met losses. But the Wednesday doubleheader was washed out, and the National League office finally got the hint from above. They okayed a twinbill for Thursday, that day’s regularly scheduled game (which the Mets would lose) plus a makeup of one of Wednesday’s rainouts (which the Mets would also lose). The NL let the other postponement from Wednesday morph into a cancellation. And as for that tie, senses were come to, and it was left as a tie.

Which is how the Mets ended 1962 at their memorable milestone of 40-120, or, technically, 40-120-1, with 1 rainout. Which is also why, if you had an eye on the 2003 Tigers as they sat at 38-118, you had to figure out how many losses they needed to land on the same plane (and not one jetting out of Houston) as the Original Mets. Lose their last six, and it’s clear. The Tigers are the worst, at 38-124. Lose at least two, and there’s a match: 120 losses then, 120 losses now. Except those 42 wins were kind of pesky if you wanted to be definitive about who was the absolute worst. A break-even run of 3-3, as impossible as it was to imagine those Tigers winning three of their final six, would give them both more wins (41) and more losses (121); we’d still have one record. The only thing they had to avoid was suddenly getting good for a week.

The 2003 Tigers got good for a week, taking five of their last six, including two on walkoffs, to finish 43-119, meaning all that losing was for nothing but draft position (picking second despite being the worst club in the majors by far—the NL and AL used to alternate—the Tigers in 2004 selected Justin Verlander). It also meant I would never again take anybody allegedly as bad as the 1962 Mets seriously when it came to a pursuit of 120 or more losses, let alone 40 or fewer wins.

This kid has legs. Until now. The 2024 White Sox — who we will see for ourselves later this month — must be respected for being as lousy as they’ve been for this long. I still find it hard to believe they will outlose the 1962 Mets. They are due for a few wins, and a few is all that is necessary to propel them toward some pedestrian win total above 40 or 42 or whatever would place them out of reach of our Originals. Honestly, I’m not sure I want this record out of the family. Kind of, because a) it would be nice for a Mets team not to be identified as The Worst Team Ever (save for Cleveland Spiders fetishists); and b) records being broken make paying attention worthwhile. But this record has had legs (if not Spider legs). We talk about the 1962 Mets to this day. We’re literally talking about the 1962 Mets today. Other than as a foil for the Mets, when was the last time you heard anybody bring up the 1962 Colt .45s?

In covering the Mets’ travels and travails in and out of Texas, Dick Young reserved a moment to mock the aforementioned day-night doubleheader in Houston as evidence of ownership “greed”.

During the matinee there were 1,638 fans in the stands. A few hours later there were only 6,568 present to see their team win its sixth straight — and a house was being given away via a home plate drawing as an added inducement.

That’s a total of 8,000 fans to see two games — with a free house thrown in. Granted marvelous Marv Throneberry isn’t the big draw in Texas that he is in New York, but the fans stayed away as if nursing a deep seated resentment.

I can’t stress enough that as miserable a human being as he proved himself in the late 1970s, he was still a helluva beat writer in the early 1960s. But nobody ever wants to acknowledge anything good about Dick Young, so never mind that. The point in excerpting his coverage here is that the 1962 Mets had Marv Throneberry. Nobody had to elaborate on what that meant in 1962, and nobody has to much explain who he is today. Marvelous Marv says it all. Original Mets says it all. Let the 2024 White Sox usurp our futility. Or not. Either way, we’ll always be us.

In Denver Tuesday night, we still were.

I’m thinking of the bottom of the second inning, with the Mets ahead of the Rockies, 2-0, and Brendan Rodgers on first after Luis Severino hit him with a pitch. Perpetually achy Kris Bryant stepped up and lined a ball into the right-center gap. Balls get lined into the Coors Field right-center and left-center gaps all the time. Center fielder Harrison Bader, prepared for such an eventuality, did a fine job of tracking it down.

Getting it back into the infield is where it became a Metsian adventure one could imagine transpiring in 1962 had the NL expanded to Colorado sooner. Bader’s throw sailed over second base as Rodgers pulled into third (fortunately, Bryant, not up for running more than ninety feet at a clip, these days, had stopped at first). Nobody had backed it up (Bryant could advance to second after all). It fell to Mark Vientos to retrieve the ball and end this discouraging but hardly lethal sequence of events with runners on second and third. At least nobody scored.

Um, thing is, Vientos picked up the ball, but didn’t get a firm grip on it, so it slipped out of his hand and landed behind him by the third-base dugout. Did I say “by” the third base dugout? It rolled into the netting that forms the dugout’s protective screen…except the netting wasn’t properly secured to the dugout’s base, so the ball didn’t roll into the netting so much as underneath it.

Ball in the dugout? Every baserunner gets to move up a base. Out of thin air, Rodgers trots home and Bryant, who wasn’t intent on passing first, is on third. Two errors are distributed, one to Bader, one to Vientos. The Rockies get a run off the Mets on a play that, if you choose to re-read Jimmy Breslin, you’ll find probably happened in some form or fashion quite often in 1962.

Beautiful.

The run should have been charged to the Coors Field grounds crew for its shabby maintenance of that screen, but it was a run for the home team, no matter whose ledger bore the brunt of it. It certainly didn’t cost the Mets what became a 6-3 loss, no more than Rodgers’s double off Vientos’s glove that plated another run did. Yeah, sure, a Met third baseman not making plays in a Met defeat seems particularly characteristic of the franchise in its infancy (or until Ed Charles came along five years later), but let’s not lay this all at the feet of Vientos or Bader or Severino (five mile-high innings pitched) or any 2024 Met in particular. Maybe there’s something telling about the nine-minute rain delay that ensued in the middle of the game. That’s nine, not ninety. There wasn’t even enough time to bother with a tarp. Or maybe the Coors Field grounds crew can’t be bothered to do more than sprinkle Diamond Dust. You don’t have many rain delays that short, but this one was shorter than the twelve minutes of “shower delays” Young cited in Houston, and those were pretty short.

Spooky! Or fitting. On a night the White Sox acted as if they have no business being lumped in with the 1962 Mets, I’d like to think the modern-day Mets, with help from the elements and a ball nobody seemed to want, were simply channeling the spirit of their ancestors.

by Greg Prince on 6 August 2024 8:30 am Strolling around Denver might have made for a lovely off day Monday, but I’d guess the Mets were happy to be called into the St. Louis satellite office to catch up on some work when all was said and done. What’s an extra time zone’s travel when you can pick up a win?

Sean Manaea looked unbothered at having to take to the Busch Stadium mound on what was originally an immaculate space within August’s scheduling grid. He also looked like somebody you’d think about penciling in as your Game One starter down the road if all works out. Ah, getting ahead of ourselves as we try to get ahead of a few other teams. Details, details, including the detail of making up a rainout. Downpours back in May and tight squeezes amid a 162-box checkerboard ensured the Mets would have to be interrupted on their already arduous road trip and add a date to their crowded summer itinerary.

But what a swell date it turned out to be.

Manaea scattered six hits over seven innings, walked nobody, and struck out ten. This is what we’re coming to know as a typical Sean Manaea outing. Great control, total command — just get him a couple of runs and we’ll be fine. The Mets got him six. Tyrone Taylor, your new two-hole hitter, drove in three. Jeff McNeil, the second-half slugger, homered for another. Most of the lineup looked alive in support of what Steve Gelbs referred to as The Sean Manaea Show, which made me think of Gilda Radner bouncing up and down on her bed as the star of The Judy Miller Show, and what Mets fan wasn’t at least figuratively jumping for joy from what had just transpired this early evening? Manaea’s showcase started at 5:15 and the game was over before eight o’clock in the East, yet I’d say this lefty is ready for prime time.

by Greg Prince on 5 August 2024 9:03 am Let’s see…nine innings coming to bat…six innings with runners reaching…two innings with runners scoring…no more than one run scoring in any one inning.

That’s not a lot of offense to work with, and the Mets didn’t make it work for them. Five base hits, four walks, one hit-by-pitch, three opposition errors, yet all of two runs on a sunny Southern California Sunday afternoon that turned cloudy when the Mets couldn’t do nearly enough with Griffin Canning — Griffin Canning, for all your canning needs — or anything at all versus three Angel relievers. The Mets’ best chance to score in the late innings came when Francisco Lindor hit a foul ball that was briefly and mistakenly called a home run before correction kicked in.

Two runs can win you a game if your pitching doesn’t allow quite that many in return runs in return. Met pitching wasn’t quite that effective. Jose Quintana gutted out five frames of three-run ball, and though the combined efforts of relievers Adam Ottavino, Danny Young and Phil Maton were close to spotless, the horse had already inched out of the barn and wandered onto I-5.

Angels 3 Mets 2, on the heels of Angels 5 Mets 4, made for a very deflating first stop on a very challenging road trip at a very critical juncture of the schedule amid a very competitive Wild Card race. It’s never a very good time to lose games, especially to a subpar opponent (not that you could tell one team’s aptitude from the other’s in this series), super-especially when you’re facing a pitcher who entered the day with a record of 3-10 alongside an ERA of 5.25 that indicated the record was not misleading. Well, now Griffin Canning, who fanned eight over five, is 4-10, and the Mets are a game-and-a-half off the playoff pace and, more concerning, a little pulseless. Since J.D. Martinez’s grand slam on Saturday night, they’ve gone eleven innings with only a tiny bit of clutch hitting and almost no scoring whatsoever. It’s not an extensive sample size, but it’s been kind of boring, which is something the Mets haven’t been all that much this season. Ostentatiously bad early. Extravagantly good later. Dull, though? Somebody needs to take the field dressed as Grimace or something.

It’s just two games, one hopes. On to St. Louis, Colorado, Seattle, wherever. The journey continues. Perhaps they can replenish their mojo somewhere along the way.

by Greg Prince on 4 August 2024 11:01 am It is one of my most deeply ingrained articles of faith that if a Met hits a grand slam, especially if a Met hits a grand slam that puts the Mets in front — especially if a Met hits a grand slam that puts the Mets ahead in the late innings of game that stands to symbolize the unstoppable momentum they have generated and are sure to continue to generate…if that happens, obviously the Mets will win.

Obviously, this does not always happen.

J.D. Martinez delivered the grand slam that catapulted the Mets from behind to ahead in the seventh inning at Angel Stadium Saturday night. They were down, 2-0, despite quality starting from David Peterson. They had run into a buzzsaw of ex-Met defense, with Kevin Pillar reminding us why he remains baseball’s Roy Kent (he’s here, he’s there, he was every fucking where in center), but here was Martinez turning it all around off another ex-Met, Hunter Strickland, a member of 2020’s Silent Generation, taking that particular journeyman to Disneyland, or at least its parking lot.

We’re up, 4-2, in the middle of seven. Get up and stretch, then settle in for the two-run lead that will stand up as long as our newest bullpen acquisition, mellifluous Huascar Brazoban, stays tonal and tends properly to setup business. He indeed strikes out his first two batters, carries the count to two-and-two on the third, and…

Too many ellipses in this story. Reader’s Digest version: Michael Stefanic singles; Nolan Schaneul walks on a full count, and Zach Neto homers.

Sadly, our honeymoon with Huascar has just been cancelled, a common occurrence every time we trade for somebody else’s unwanted reliever, because whether his last name is Maton or Stanek or Brazoban, they all blow up at least once within their first three Met appearances, and we can never look at them with wholly trusting eyes again. Of more immediate concern, math (or “maths,” as they said on Ted Lasso) informs us that the 4-2 lead has become a 5-4 deficit. A team teeming with momentum shakes off that setback in the eighth and/or ninth, grabs the lead back, nails the game down, stays in Wild Card position, and inches up on its division rivals in the process.

Momentum, however, had oozed out of the Mets. Nothing was done with Mark Vientos’s leadoff double in the eighth, and nothing else good happened from there. Elsewhere, the catchable Phillies lost. The Braves lost. The Diamondbacks lost. But the Padres won, and now we are fourth in a race that bestows medals on only three. We got help, but not all the help in the world. We can watch just so much of the scoreboard in search of others’ L’s. Just one game, lots of games to go. Still, Roy Kent always had the right four-letter word for such a development.

J.D.’s big blow was a jolt of late-night caffeine for an offense that, like some of us attempting to follow the Mets from three time zones east, needed nudging. The first through sixth, whether due to Pillar’s defensive wizardry or the frustrating effectiveness of Angel starter Jose Soriano, could have been sponsored by a mattress company. L.A. of A closer Ben Joyce in the eighth and ninth might as well have been pouring Sleepytime herbal tea to Met batters. Whichever side of the country the Mets are on, they need to remain alert to the possibility of plating multiple runs in multiple innings.

Always happy to help bring the obvious to light.

Nineteen times a Met has hit a grand slam in what became a Met loss. Logically, of course that can happen. Four runs are four runs and therefore can be superceded by five or more if they are not augmented by additional Met runs. It’s the same graspable form of calculation that allowed me to understand at a young age that Steve Carlton could strike out nineteen Mets in 1969 yet go down to defeat because Ron Swoboda bashed two homers while Carlton’s Cardinal teammates scored only thrice on their record-setting lefty’s behalf. Emotionally, though? No way! A grand slam is such a huge deal it has its own name! GRAND SLAM! One swing! Four runs! Exclamation points everywhere! Including on the Roy Kentian epithets that presumably flew across Metsopotamia in sync with Neto’s three-run bomb over Southern California.

Sigh…

|

|

I’m gonna guess Goodman wouldn’t mind that assessment, for he, too, is a Mets fan. Takes one to write one like this. The author, in a note introducing his work, let me know he’s been rooting for this team since 1962. He also first wrote about a Singer pitching for the Mets in 1991’s In Days of Awe. The pitcher at that juncture in Mets history was the great Joe Singer. We could have used a great pitcher right around then. Goodman decided some three decades hence that we needed a sequel. Thus, Jess, son of Joe. Two Singers. Two pitchers. Two Mets. Loads of talent…including Eric Goodman in bringing this pair to us.

I’m gonna guess Goodman wouldn’t mind that assessment, for he, too, is a Mets fan. Takes one to write one like this. The author, in a note introducing his work, let me know he’s been rooting for this team since 1962. He also first wrote about a Singer pitching for the Mets in 1991’s In Days of Awe. The pitcher at that juncture in Mets history was the great Joe Singer. We could have used a great pitcher right around then. Goodman decided some three decades hence that we needed a sequel. Thus, Jess, son of Joe. Two Singers. Two pitchers. Two Mets. Loads of talent…including Eric Goodman in bringing this pair to us.